Abstract

The replication and packaging of the rotavirus genome, comprising 11 segments of double-stranded RNA, take place in specialized compartments called viroplasms, which are formed during infection and involve a coordinated interplay of multiple components. Two rotavirus nonstructural proteins, NSP2 (with nucleoside triphosphatase, single-stranded RNA [ssRNA] binding and helix-destabilizing activities) and NSP5, are essential in these events. Previous structural analysis of NSP2 showed that it is an octamer in crystals, obeying 4-2-2 crystal symmetry, with a large 35-Å central hole along the fourfold axis and deep grooves at one of the twofold axes. To ascertain that the solution structure of NSP2 is the same as that in the crystals and investigate how NSP2 interacts with NSP5 and RNA, we carried out single-particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) analysis of NSP2 alone and in complexes with NSP5 and ssRNA at subnanometer resolution. Because full-length NSP5 caused severe aggregation upon mixing with NSP2, the deletion construct NSP566-188 was used in these studies. Our studies show that the solution structure of NSP2 is same as the crystallographic octamer and that both NSP566-188 and ssRNA bind to the grooves in the octamer, which are lined by positively charged residues. The fitting of the NSP2 crystal structure to cryo-EM reconstructions of the complexes indicates that, in contrast to the binding of NSP566-188, the binding of RNA induces noticeable conformational changes in the NSP2 octamer. Consistent with the observation that both NSP5 and RNA share the same binding site on the NSP2 octamer, filter binding assays showed that NSP5 competes with ssRNA binding, indicating that one of the functions of NSP5 is to regulate NSP2-RNA interactions during genome replication.

One of the least understood stages in viral morphogenesis is genome replication and packaging. This is particularly true with complex viruses such as rotavirus, a member of the Reoviridae family and the major cause of infantile gastroenteritis (18). Rotavirus is a large icosahedral virus composed of three concentric capsid layers that enclose the genome. Its genome consists of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which encode six structural viral proteins (VPs) and six nonstructural proteins (NSPs) (12). Removal of the outer capsid layer composed of VP4 and VP7 during cell entry triggers the endogenous transcription of the genome in the resulting double-layer particles. The transcription of the dsRNA segments into capped mRNA is assisted by the viral polymerase VP1 (39) and the capping enzyme VP3 (7, 21), which, possibly as heterodimers, are attached to the inside surface of the inner VP2 layer of the virion (27). The transcripts exit from the double-layer particles through the channels at the fivefold axis in the VP6 layer (20). These mRNA molecules function as templates for the progeny RNA and encode all the viral proteins (12).

Replication and packaging of the viral genome into the viral capsids takes place in specialized, cytoplasmic compartments called viroplasms, which are formed early in infection. These are large, nonmembrane bound, electron-dense structures rich in viral RNA, the viral structural proteins VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP6 (13, 25) and the nonstructural proteins NSP2, NSP5, and NSP6 (36). Several studies, including recent RNA interference studies, have demonstrated that both NSP2 and NSP5 are critical for the nucleation of viroplasms and for virus replication (5, 31).

NSP2 is a 35-kDa basic protein that exhibits nucleoside triphosphatase (NTPase) (33), sequence-independent single-stranded RNA (ssRNA)-binding (33), and nucleic acid helix-destabilizing activities (35, 36). X-ray crystallographic analysis of NSP2 has shown that, in crystals, NSP2 exists as an octamer (16). The monomeric subunit of NSP2 has two distinct domains separated by a deep cleft. Based on the partial structural similarity with histidine triad proteins, NTP-binding is predicted to reside within a cleft between the two domains (15). The association of the monomeric subunits according to crystallographic 4-2-2 symmetry results in a donut-shaped octamer with a 35-Å central hole along the fourfold axis and deep grooves that run diagonally across one of the twofold axes. These grooves, lined by positively charged residues, are predicted to be ssRNA-binding sites.

The binding partner of NSP2 in the viroplasm formation is NSP5. It is a phosphoprotein that exists in multiple phosphorylated isoforms, with apparent molecular masses ranging from 26 to 35 kDa during the course of rotavirus replication (3). Although how NSP5 gets phosphorylated is unclear, cellular kinases (9, 11, 30) and NSP2 (1, 6, 40) are implicated in NSP5 phosphorylation. Recent biochemical studies have suggested regions in NSP5 that are important for multimerization (38), viroplasm formation (11, 24), and binding to NSP2 (10).

To investigate the solution structure of NSP2 and how the protein binds to multiple ligands, such as NSP5 and RNA, we carried out single-particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) analysis of the NSP2, NSP2-NSP5, and NSP2-RNA complexes at subnanometer resolution. The single-particle cryo-EM technique is a well-established technique and has been used to study both small and large macromolecular assemblies with and without symmetry at subnanometer resolutions (17). Compared to the sizes of many of the specimens studied by this technique, NSP2 is relatively small; assuming that it is an octamer in solution, the total molecular mass is about ∼280 kDa. Our structural analysis represents a successful application of the single-particle cryo-EM technique to such a small specimen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of NSP2 and NSP5.

NSP2 from the SA11 strain of rotavirus was expressed in the Escherichia coli strain SG13009 (QIAGEN) with a six-His tag at the C terminus and purified as described before (16). This His tag construct is the same as that used in previous biochemical characterizations of NSP2, including its NTPase activity, RNA binding (33), and in vitro phosphorylation of NSP5 (40) and crystallographic analysis (16). Based on these studies, the conformationally flexible His tag was considered noninterfering with either RNA or NSP5 binding. The NSP5 (SA11 strain) gene (corresponding to either the full length or the residues from 66 to 188) was cloned between the SapI and XmaI sites in the vector pTYB11 with a self-cleavable intein tag (IMPACT-CN system; New England Biolabs) and expressed in E. coli strain ER2566. Expressed protein was purified using a chitin column according to the manufacturer's protocol for the IMPACT-CN system.

Cryo-EM and image analysis.

For cryo-EM studies, specimens (NSP2, NSP2-NSP5, and NSP2-RNA complexes) were embedded in a thin layer of ice on a holey carbon grid (Quantifoil Micro Tools GmbH, Jena, Germany) using standard procedures (8). Frozen-hydrated specimens were imaged using a JEM2010F electron microscope equipped with a field emission gun and operated at 200 kV. Images were recorded at ×60,000 magnification on a Gatan 4k- by 4k-pixel charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera with a dose of ∼15 to 20 e−/Å2 per image frame. For the NSP2-NSP566-188 complex, purified NSP2 was mixed with NSP566-188, both at 0.4 mg/ml concentration, and incubated in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 50 mM NaCl for 1 h before freezing. For the NSP2-RNA complex, purified NSP2 (0.4 mg/ml, ∼10 μM) was mixed with A8-RNA (100 μM) in the same buffer and incubated for 1 h on ice before freezing.

Single-particle cryo-EM analysis, including particle picking, classification, and three-dimensional reconstruction, was performed using the EMAN software package (22). Particles were selected from individual CCD frames (with an effective pixel size of 1.81 Å) and corrected for contrast transfer function effects. From these particles, an initial model with a C4 symmetry was generated using EMAN as described previously (22). Reference-based iterative refinement using D4 symmetry was then carried out to obtain the final reconstruction. The resolution of the reconstruction was assessed using the Fourier shell correlation method, as implemented in EMAN, by comparing the three-dimensional models computed from even- and odd-numbered particles in a data set using 0.5 criteria. The three-dimensional density map was visualized by using Chimera (14). The fitting of X-ray structure into cryo-EM maps was carried out using NORMA (http://www.igs.cnrs-mrs.fr/elnemo/NORMA/) (32), which employs a flexible docking procedure based on normal mode analysis.

Filter binding assay.

To examine the inhibition of RNA binding by NSP5 in this experiment, A8 oligonucleotide (1.5 μM), labeled with [32P]pCp at the 3′ end (Ambion), was mixed with NSP2 (0.1 μM) in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris and 50 mM NaCl at pH 8.0 and then incubated at room temperature for 30 min. NSP5 at different concentrations was then added to the NSP2-(A8-RNA) mixture and incubated for another 20 min. Each of these samples (with different concentrations of NSP5) and controls NSP2-(A8-RNA) and A8-RNA was individually passed through nitrocellulose filters (0.45-μm pore size; Millipore HA) and washed with the same buffer mentioned above. The radioactivity remaining on the filter was determined by using a scintillation spectrometer.

RESULTS

Solution structure of NSP2 is the same as that in crystals.

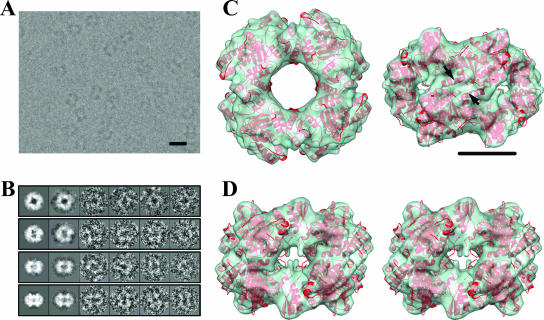

To examine whether the solution structure of NSP2 is the same as the crystallographic octameric structure and also to obtain a native unliganded cryo-EM structure of NSP2 that would be more appropriate for subsequent comparative analysis with liganded NSP2 structures, we first determined the cryo-EM structure of NSP2 alone. Cryo-EM images of NSP2 in vitreous ice recorded on a 4k-by-4k CCD camera showed several donut-shaped particles (Fig. 1A). These particles have dimensions similar to those expected from the crystallographic NSP2 octamer. The class-averaged images obtained from the boxed particles (Fig. 1B) indicated the presence of D4 (4-2-2) symmetry. The reconstruction from ∼8,882 boxed particles extracted from the 16 CCD images, spanning a range of defocus values from 1.6 μm to 2.9 μm, was computed using EMAN (22) with appropriate contrast transfer function corrections imposing the D4 (4-2-2) symmetry (Fig. 1C). The reconstructions with lower D2 or C4 symmetry also yielded similar donut-shaped structures, although the noise level was slightly higher with these reconstructions. The resolution of the reconstruction, as assessed by Fourier shell correlation, was ∼8 Å (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). At this resolution, several α-helices can be identified (Fig. 1D). The reconstruction has dimensions similar to those of the crystallographic octamer and exhibits all of the structural features, including the 35-Å central hole and prominent grooves (Fig. 1C). The fitting of the NSP2 X-ray structure into the cryo-EM reconstruction was carried out by eye, initially using both the monomer and octamer and later more quantitatively using NORMA (32), which employs normal mode analysis. The crystallographic octamer fitted well into the cryo-EM reconstruction, with a correlation coefficient (CC) of 0.8, indicating no significant alterations between the crystallographic and cryo-EM octamers.

FIG. 1.

Solution structure of NSP2 is the same as the crystallographic octamer. (A) A sample cryo-EM image of NSP2 embedded in ice was recorded with an underfocus of ∼2 μm. (B) Selected projections and corresponding class-averaged and raw particle images used in the reconstruction (see Table S1 in the supplemental material for more details). Scale bar = 100 Å. (C) Cryo-EM reconstruction (green) of NSP2 octamer at ∼8-Å resolution (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) shown as a semitransparent surface, with the fitted X-ray structure (red ribbon) of the NSP2 octamer as viewed along the fourfold axis (left) and one of the two twofold axes (right) of the 4-2-2 symmetric structure. Alpha-helices resolved at this resolution are shown by arrows. Scale bar = 50 Å. (D) Stereo view along one of the two twofold axes showing the deep grooves.

NSP5 binds to the twofold axes of the NSP2 octamer.

To address the question of how NSP2 octamer binds to NSP5, a critical binding partner in the formation of the viroplasm, we carried out cryo-EM studies on NSP2-NSP5 complexes. Initial attempts with the full-length (His-tagged and intein fusion) constructs of NSP5 (198 amino acids) were unsuccessful. Although the protein could be expressed and purified, immediate and almost complete precipitation of the native NSP5 was observed when it was mixed with NSP2 and, hence, such preparations were not suitable for single-particle cryo-EM analysis. Several other constructs of NSP5 were tried, and the results were essentially the same, either significant precipitation upon mixing with NSP2 or severe aggregation in the cryo-EM images. Based on previous studies, which showed that the C-terminal end of NSP5 is the multimerization domain (38), and our peptide-array analysis (data not shown), which indicated possible regions in the NSP5 sequence that can bind to NSP2, we made a construct of NSP5 that included residues 66 to 188 (NSP566-188). This abridged construct was found to be suitable for cryo-EM studies of NSP2-NSP5 complexes.

For cryo-EM studies, NSP566-188 was mixed in excess with NSP2 and cryo-EM imaging and subsequent data processing with 6,700 particles from 39 CCD images (defocus range 1.6 μm to 3 μm) were carried out using protocols similar to those used with the cryo-EM analysis of the native NSP2. The only difference was that, after obtaining a preliminary reconstruction, a multirefinement option was invoked with two models, corresponding to native NSP2 and NSP566-188-bound NSP2, to eliminate the unbound NSP2 and select only those particles that had bound NSP566-188. With this multirefinement option, there was a significant improvement in the overall quality of the reconstruction, including better definition of the bound NSP566-188 and improvement in the resolution from 10 Å to 9 Å, as indicated by the Fourier shell correlation statistics.

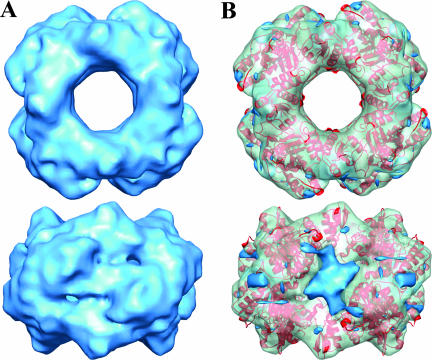

Cryo-EM reconstructions of NSP2-NSP566-188 complexes resemble the reconstructions of the native NSP2 except for the presence of extra mass at each of the twofold axes of the 4-2-2 symmetric octamer that can be attributed to the bound NSP566-188 (Fig. 2A). The major portion of this extra mass, however, is along the grooves at one of the twofold axes. The other regions in the reconstruction correspond well with the native NSP2 octamer structure, which appears unaffected by the binding of NSP566-188, as indicated by fitting of the crystallographic octamer using NORMA (CC, 0.79) (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

NSP5 binds to the grooves of the NSP2 octamer. (A) Cryo-EM reconstruction of NSP2-NSP5 (residues 66 to 188) at ∼9-Å resolution (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) viewed along the fourfold axis (top) and perpendicular to the groove (bottom) is shown in blue. (B) NSP2-NSP5 reconstruction fitted with NSP2 X-ray structure (red ribbon) in the same orientation as in panel A. The density attributed to the NSP5 fragment (identified from the difference map) is shown in blue, whereas the rest of the structure is shown as a semitransparent surface in green.

The fitting of the crystallographic NSP2 octamer into the cryo-EM of the NSP2-NSP566-188 complex indicates several regions in the NSP2 that interact with the extra mass density. These segments that interact with NSP566-188 include the C-terminal α helix, the loop between residues 291 to 302, the loops between residues 64 to 68 and 179 to 183, and the helix formed by residues 232 to 251 (see Fig. 4A). These segments predominantly map to the positively charged surface on the electrostatic potential surface of the octamer. Based on the volume occupied by the extra mass, computed using a contour level that represented 100% mass for NSP2, the extra mass accounts for a total of 55 kDa, calculated assuming a protein density of 1.30 g/cm3 in the octamer or about ∼7 kDa per monomeric subunit of NSP2. Given the molecular mass of the NSP566-188 construct, ∼14 kDa, this extra mass represents about 50% of the total mass of NSP566-188 construct.

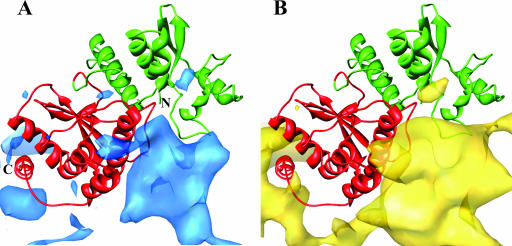

FIG. 4.

Comparison of binding sites of NSP5 (A) and RNA (B) on NSP2. The atomic model of NSP2 is shown in ribbon with N-terminal and C-terminal domains colored in green and red, respectively. In panel A, the density corresponding to NSP5 from the NSP2-NSP5 reconstruction is shown in blue, and in panel B, the density corresponding to RNA from the NSP2-RNA reconstruction is shown in yellow. The binding sites for both NSP5 and RNA overlap substantially.

RNA and NSP5 share the same binding site on the NSP2 octamer.

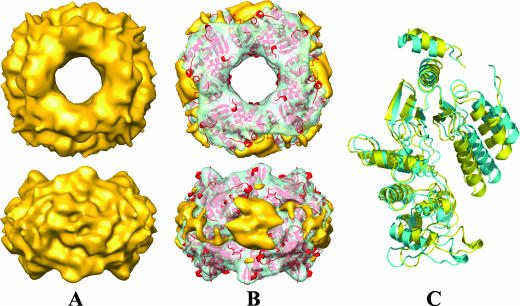

To examine how NSP2 binds to RNA, we carried out similar cryo-EM studies. In these experiments, we used an oligoribonucleotide with eight adenines (A8). The ability of such a nucleotide to bind NSP2 was confirmed using a filter binding assay with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide of the same length and sequence in the presence of 50 mM NaCl. At this salt concentration, the assay showed a saturable binding of A8-RNA with an equilibrium dissociation constant of 0.1 μM (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The cryo-EM analysis with A8-RNA was carried out under the same conditions. The reconstruction of the NSP2-RNA complex was carried out using 5,540 particles from 24 CCD images with defocus values ranging from 1.2 to 3.0 μm using the same procedures as those with the NSP2-NSP5 complexes, including the multirefinement option (Fig. 3A). To analyze the regions that would represent bound RNA and any possible structural differences because of ligand binding, we computed difference maps using either the crystallographic octamer blurred to 8.5 Å or the cryo-EM structure of the native NSP2. These difference maps showed that A8-RNA wraps around NSP2 octamer (Fig. 3B) with binding regions very similar to the NSP5 binding sites (Fig. 4B). The fitting of the X-ray structure of the NSP2 octamer into the NSP2-(A8-RNA) reconstruction using NORMA (CC, 0.76) indicated possible conformational changes due to RNA binding in NSP2, in which the two domains of the monomeric subunit, separated by a flexible hinge, move closer to one another (Fig. 3C). The domain movement appears to be similar to that found in the recent structure of the NSP2 of group C rotavirus (34). The extra mass density in the reconstruction that can be attributed to bound RNA accounts for ∼4 molecules of A8-RNA, calculated as described above for NSP566-188, per NSP2 monomer.

FIG. 3.

RNA also binds to the grooves of the NSP2 octamer and induces conformational changes. (A) Cryo-EM reconstruction of NSP2-RNA at 8.5-Å resolution (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), was viewed along the fourfold axis (top) and perpendicular to groove (bottom), is shown in yellow. (B) NSP2-RNA reconstruction with the fitted NSP2 X-ray structure (red ribbon) in the same orientation as in panel A. RNA (identified from the difference map) is rendered in yellow, whereas the rest of the structure is shown as a semitransparent surface in green. (C) Superposition of the native and the fitted NSP2 subunits, in cyan and yellow ribbon presentation, respectively, are shown to indicate possible conformational changes in NSP2 upon RNA binding.

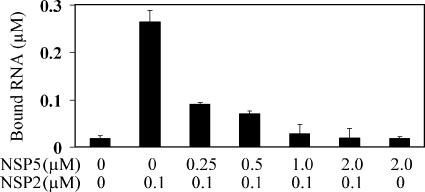

NSP5 inhibits RNA binding of NSP2.

Noticing the overlapping binding sites for RNA and NSP5 on the NSP2 octamer, we next examined whether the binding of NSP566-188 inhibited the binding of RNA or vice versa using a filter binding assay. We labeled the same A8-RNA used in the cryo-EM studies at the 3′ end with [32P]pCp. Without NSP566-188, RNA bound to NSP2 quite efficiently. However, in the presence of NSP566-188, the amount of RNA bound to NSP2 decreased and excess NSP566-188 almost completely inhibited RNA binding to NSP2 (Fig. 5). These results, consistent with the structural observations, suggest that NSP566-188 outcompetes RNA for binding to NSP2.

FIG. 5.

NSP5 inhibits RNA binding to NSP2. Results from a filter binding assay show the amount of radiolabeled RNA bound to NSP2 at various concentrations of NSP5. The controls are the first bar, showing the bound RNA without any protein, and the last bar, showing bound RNA with NSP5 (2 μM) alone. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Our cryo-EM analysis of the native NSP2 clearly indicates that, in solution, the structure of the NSP2 octamer is the same as that in the crystals. Such an oligomeric structure may be required to provide a suitable scaffold to integrate all of the functions of NSP2, such as the formation of viroplasms, genome replication, and packaging, that involve several binding partners, such as NSP5, VP1, and ssRNA. As shown in our studies, the binding of two of these ligands, RNA and NSP5, to the grooves and the other subunit interfaces of the NSP2 octamer is consistent with this idea. The only other viral protein among segmented dsRNA viruses with properties and functions somewhat similar to those of NSP2 is P4 of cystoviruses (23). However, NSP2 is structurally distinct from P4, which, unlike NSP2, is a structural protein.

Our initial experiments with the full-length NSP5 indicated that it induces aggregation when mixed with NSP2. Considering that these proteins are involved in the formation of viroplasms, which are essentially protein aggregates, such a behavior is perhaps to be expected. The deletion of the first 66 residues produced complexes with minimal aggregation, thereby suggesting that the first 66 residues are important for viroplasm formation. Our structural finding that a major portion of NSP566-188 binds to the grooves, which are lined by basic residues, is consistent with the observation that NSP5 protein is slightly acidic and also with the NSP2 binding regions identified by two-hybrid and immunoprecipitation studies (10). These studies identified two regions in the NSP5 sequence that are important for binding to NSP2. One of these regions in the N-terminal part of the sequence is not present in our abridged construct used in the cryo-EM studies, and the other region has a long stretch of acidic residues (residues 151 to 168).

The observed density due to NSP566-188 in the NSP2-NSP566-188 reconstruction is centered on each of the four twofold axes near the grooves of the octamer, suggesting that NSP5 binds to NSP2 as a dimer. That is, four dimers of NSP5 bind to one octamer of NSP2. It is possible that the mass density near each of the twofold axes is due to a monomer and that the imposition of the D4 symmetry during the reconstruction procedures confers twofold symmetric appearance. However, the formation of the dimer is consistent with size exclusion chromatography of our abridged form of NSP5 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) and with earlier immunoprecipitation studies of native NSP5 (26).

Based on the occupied volume, the extra mass due to NSP566-188 in the NSP2-NSP566-188 reconstruction accounts for only 50% of the expected mass of the NSP566-188 construct, assuming a 1:1 stoichiometric binding. This suggests that a significant portion of NSP5 is flexible or disordered. This interpretation is consistent with sequence analysis of NSP5 using FoldIndex (28) and secondary structure predictions algorithms (4), which indicate that NSP5 is largely unstructured with few secondary structural elements separated by large loops. Considering that it is an essential part of the viroplasm, the site for genome replication/packaging and assembly, the flexible nature of NSP5 may be necessary to impart the dynamics necessary to coordinate these activities.

Our structural analysis of NSP2-RNA complexes indicates that RNA and NSP5 bind to very similar positively charged regions near the twofold axes of the octamer. The binding of RNA predominantly to the positively charged residues may account for the nonspecific nature of this interaction. One suggested role of NSP2, considering its RNA binding and helix-destabilizing activities, is that it unravels any secondary structure in the viral RNA template to facilitate packaging and replication by the viral polymerase machinery. Sequence-independent binding may be necessary for interacting with all of the 11 transcripts, which raises the question of how NSP2 avoids interacting with cellular RNA. Perhaps the reason is its confined localization to the viroplasms, which are sites for genome replication composed exclusively of viral proteins and viral transcripts. In addition to the basic residues, the binding interface in the NSP2-RNA structure involves several aromatic residues, such as Phe43, Phe184, Phe245, Phe300, Tyr230, and Tyr242, which may be important for preferential binding to ssRNA. Such preferential binding to ssRNA may confer the helix-destabilizing activity to NSP2. The significance of the conformational changes in the NSP2 caused by RNA binding is presently unclear. It is possible that such conformational changes may have a role in NSP2 binding to other viral proteins such as VP1 (19) and VP2 (2), directly or indirectly during the course of viral genome replication and packaging.

One unanticipated result from our studies was the overlapping binding sites for NSP5 and RNA. Consistent with this structural observation, the filter-binding assay indicated that NSP5 outcompetes RNA in binding to NSP2. These results suggest that, in addition to its role in the formation of viroplasm, NSP5 may have a regulatory role in the RNA binding activity of NSP2 during virus replication. Such a regulatory function could involve the complete inhibition of RNA binding at certain time points and the unmasking of some of the RNA binding sites, depending upon the concentration of the nascent transcripts and their affinities to NSP2 at various times during the process of replication. This regulatory function is likely coupled to the phosphorylation of NSP5. Previous studies have shown that, ∼2 h postinfection, NSP5 becomes increasingly phosphorylated (3). It is unclear how NSP5 gets phosphorylated. Protein kinases, such as casein kinase II (11) and NSP2 through its NTPase activity (40), have also been suggested to be involved in NSP5 phosphorylation. In the NSP2 octamer, the NTP binding sites are located in the cleft region of each monomer in close vicinity to the groove and the NSP5 binding region, supporting the possibility of the transfer of phosphate from NSP2 to NSP5. In our studies, the bacterially expressed NSP5 is not phosphorylated, and further studies are required to understand the effects of NSP5 phosphorylation in NSP2-NSP5 and NSP2-NSP5-RNA interactions.

From our cryo-EM studies of the native NSP2, earlier crystallographic studies (16), which show an extensive buried surface area between the subunits, and biochemical analysis of a temperature-sensitive mutant rotavirus (37), it is reasonable to assume that the octameric structure of NSP2 is the functional form. While the NTPase activity can be attributed to the monomeric subunit (6), based on the structural and site-directed mutagenesis analyses, binding to NSP5 and RNA as shown here requires octamer formation. One intriguing feature of the NSP2 octamer is the 35-Å central hole. In the other donut-shaped RNA binding protein structures, such as the Sm complex, exosome, and PNPase, the central hole is proposed for RNA binding and subsequent translocation (29). In the NSP2 octamer, this hole is lined by neutral residues and our cryo-EM studies show that this hole is not used for RNA binding. Previous studies have suggested that NSP2 interacts with VP1 (19), the viral polymerase responsible for negative strand synthesis and duplex formation, and, via NSP5, with VP2 (2), which forms the inner capsid layer. One interesting possibility, pending further studies, is that the central hole of the NSP2 octamer could be used as a protective environment for newly synthesized dsRNA emerging from VP1 or as a passive conduit for its packaging during the assembly of the VP2 capsid layer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AI-36040 (B.V.V.P.) and DK-30144 (M.K.E.) and the Welch Foundation (B.V.V.P.).

We acknowledge the use of the cryo-EM facilities at the NIH-funded National Center for Macromolecular Imaging (P41RR02250). We thank Z. Taraporewala, J. Patton, and T. Wensel for helpful discussions and T. Palzkill and Z. Zhang for peptide array analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 August 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afrikanova, I., E. Fabbretti, M. C. Miozzo, and O. R. Burrone. 1998. Rotavirus NSP5 phosphorylation is up-regulated by interaction with NSP2. J. Gen. Virol. 79:2679-2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berois, M., C. Sapin, I. Erk, D. Poncet, and J. Cohen. 2003. Rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP5 interacts with major core protein VP2. J. Virol. 77:1757-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackhall, J., M. Munoz, A. Fuentes, and G. Magnusson. 1998. Analysis of rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP5 phosphorylation. J. Virol. 72:6398-6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryson, K., L. J. McGuffin, R. L. Marsden, J. J. Ward, J. S. Sodhi, and D. T. Jones. 2005. Protein structure prediction servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W36-W38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campagna, M., C. Eichwald, F. Vascotto, and O. R. Burrone. 2005. RNA interference of rotavirus segment 11 mRNA reveals the essential role of NSP5 in the virus replicative cycle. J. Gen. Virol. 86:1481-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpio, R. V., F. D. Gonzalez-Nilo, H. Jayaram, E. Spencer, B. V. Prasad, J. T. Patton, and Z. F. Taraporewala. 2004. Role of the histidine triad-like motif in nucleotide hydrolysis by the rotavirus RNA-packaging protein NSP2. J. Biol. Chem. 279:10624-10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, D., C. L. Luongo, M. L. Nibert, and J. T. Patton. 1999. Rotavirus open cores catalyze 5′-capping and methylation of exogenous RNA: evidence that VP3 is a methyltransferase. Virology 265:120-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubochet, J., M. Adrian, J. J. Chang, J. C. Homo, J. Lepault, A. W. McDowall, and P. Schultz. 1988. Cryo-electron microscopy of vitrified specimens. Q. Rev. Biophys. 21:129-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichwald, C., G. Jacob, B. Muszynski, J. E. Allende, and O. R. Burrone. 2004. Uncoupling substrate and activation functions of rotavirus NSP5: phosphorylation of Ser-67 by casein kinase 1 is essential for hyperphosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:16304-16309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichwald, C., J. F. Rodriguez, and O. R. Burrone. 2004. Characterization of rotavirus NSP2/NSP5 interactions and the dynamics of viroplasm formation. J. Gen. Virol. 85:625-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eichwald, C., F. Vascotto, E. Fabbretti, and O. R. Burrone. 2002. Rotavirus NSP5: mapping phosphorylation sites and kinase activation and viroplasm localization domains. J. Virol. 76:3461-3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estes, M. K. 2001. Rotaviruses and their replication, p. 1747-1785. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estes, M. K., and J. Cohen. 1989. Rotavirus gene structure and function. Microbiol. Rev. 53:410-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goddard, T. D., C. C. Huang, and T. E. Ferrin. 2005. Software extensions to UCSF chimera for interactive visualization of large molecular assemblies. Structure 13:473-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayaram, H., M. K. Estes, and B. V. Prasad. 2004. Emerging themes in rotavirus cell entry, genome organization, transcription and replication. Virus Res. 101:67-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayaram, H., Z. Taraporewala, J. T. Patton, and B. V. Prasad. 2002. Rotavirus protein involved in genome replication and packaging exhibits a HIT-like fold. Nature 417:311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang, W., and S. J. Ludtke. 2005. Electron cryomicroscopy of single particles at subnanometer resolution. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15:571-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapikian, A. Z., Y. Hoshino, and R. M. Chanoch. 2001. Rotaviruses, p. 1787-1833. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 19.Kattoura, M. D., X. Chen, and J. T. Patton. 1994. The rotavirus RNA-binding protein NS35 (NSP2) forms 10S multimers and interacts with the viral RNA polymerase. Virology 202:803-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawton, J. A., M. K. Estes, and B. V. Prasad. 1997. Three-dimensional visualization of mRNA release from actively transcribing rotavirus particles. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:118-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, M., N. M. Mattion, and M. K. Estes. 1992. Rotavirus VP3 expressed in insect cells possesses guanylyltransferase activity. Virology 188:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludtke, S. J., P. R. Baldwin, and W. Chiu. 1999. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 128:82-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancini, E. J., D. E. Kainov, J. M. Grimes, R. Tuma, D. H. Bamford, and D. I. Stuart. 2004. Atomic snapshots of an RNA packaging motor reveal conformational changes linking ATP hydrolysis to RNA translocation. Cell 118:743-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohan, K. V., J. Muller, I. Som, and C. D. Atreya. 2003. The N- and C-terminal regions of rotavirus NSP5 are the critical determinants for the formation of viroplasm-like structures independent of NSP2. J. Virol. 77:12184-12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton, J. T. 1995. Structure and function of the rotavirus RNA-binding proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2633-2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poncet, D., P. Lindenbaum, R. L'Haridon, and J. Cohen. 1997. In vivo and in vitro phosphorylation of rotavirus NSP5 correlates with its localization in viroplasms. J. Virol. 71:34-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad, B. V., R. Rothnagel, C. Q. Zeng, J. Jakana, J. A. Lawton, W. Chiu, and M. K. Estes. 1996. Visualization of ordered genomic RNA and localization of transcriptional complexes in rotavirus. Nature 382:471-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prilusky, J., C. E. Felder, T. Zeev-Ben-Mordehai, E. H. Rydberg, O. Man, J. S. Beckmann, I. Silman, and J. L. Sussman. 2005. FoldIndex: a simple tool to predict whether a given protein sequence is intrinsically unfolded. Bioinformatics 21:3435-3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruijn, G. J. 2005. Doughnuts dealing with RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:562-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sen, A., D. Agresti, and E. R. Mackow. 2006. Hyperphosphorylation of the rotavirus NSP5 protein is independent of serine 67 or NSP2, and the intrinsic insolubility of NSP5 is regulated by cellular phosphatases. J. Virol. 80:1807-1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silvestri, L. S., Z. F. Taraporewala, and J. T. Patton. 2004. Rotavirus replication: plus-sense templates for double-stranded RNA synthesis are made in viroplasms. J. Virol. 78:7763-7774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suhre, K., J. Navaza, and Y.-H. Sanejouand. 2006. NORMA: a tool for flexible fitting of high-resolution protein structures into low-resolution electron-microscopy-derived density maps. Acta Cryst. 62:1098-1100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Taraporewala, Z., D. Chen, and J. T. Patton. 1999. Multimers formed by the rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP2 bind to RNA and have nucleoside triphosphatase activity. J. Virol. 73:9934-9943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taraporewala, Z. F., X. Jiang, R. Vasquez-Del Carpio, H. Jayaram, B. V. Prasad, and J. T. Patton. 2006. Structure-function analysis of rotavirus NSP2 octamer by using a novel complementation system. J. Virol. 80:7984-7994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taraporewala, Z. F., and J. T. Patton. 2001. Identification and characterization of the helix-destabilizing activity of rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP2. J. Virol. 75:4519-4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taraporewala, Z. F., and J. T. Patton. 2004. Nonstructural proteins involved in genome packaging and replication of rotaviruses and other members of the Reoviridae. Virus Res. 101:57-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taraporewala, Z. F., P. Schuck, R. F. Ramig, L. Silvestri, and J. T. Patton. 2002. Analysis of a temperature-sensitive mutant rotavirus indicates that NSP2 octamers are the functional form of the protein. J. Virol. 76:7082-7093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres-Vega, M. A., R. A. Gonzalez, M. Duarte, D. Poncet, S. Lopez, and C. F. Arias. 2000. The C-terminal domain of rotavirus NSP5 is essential for its multimerization, hyperphosphorylation and interaction with NSP6. J. Gen. Virol. 81:821-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valenzuela, S., J. Pizarro, A. M. Sandino, M. Vásquez, J. Fernández, O. Hernández, J. Patton, and E. Spencer. 1991. Photoaffinity labeling of rotavirus VP1 with 8-azido-ATP: identification of the viral RNA polymerase. J. Virol. 65:3964-3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vende, P., Z. F. Taraporewala, and J. T. Patton. 2002. RNA-binding activity of the rotavirus phosphoprotein NSP5 includes affinity for double-stranded RNA. J. Virol. 76:5291-5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.