Abstract

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a central regulator of cellular responses to hypoxia, and under normal oxygen tension the catalytic α subunit of HIF is targeted for ubiquitin-mediated destruction via the VHL-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Principally known for its association with oncogenesis, HIF has been documented to have a role in the antibacterial response. Interferons, cytokines with antiviral functions, have been shown to upregulate the expression of HIF-1α, but the significance of HIF in the antiviral response has not been established. Here, using renal carcinoma cells devoid of VHL or reconstituted with functional wild-type VHL or VHL mutants with various abilities to negatively regulate HIF as an ideal model system of HIF activity, we show that elevated HIF activity confers dramatically enhanced resistance to vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-mediated cytotoxicity. Inhibition of HIF activity using a small-molecule inhibitor, chetomin, enhanced cellular sensitivity to VSV, while treatment with hypoxia mimetic CoCl2 promoted resistance. Similarly, targeting HIF-2α by RNA interference also enhanced susceptibility to VSV. Expression profiling studies show that upon VSV infection, the induction of genes with known antiviral activity, such as that encoding beta interferon (IFN-β), is significantly enhanced by HIF. These results reveal a previously unrecognized role of HIF in the antiviral response by promoting the expression of the IFN-β gene and other genes with antiviral activity upon viral infection.

Members of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) family of transcription factors are important regulators of adaptive cellular responses to hypoxia, since they regulate the expression of genes that promote angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, anaerobic energy production, and cell survival (4). Overexpression of HIF is a hallmark of diverse tumors, and its constitutive activation is frequently associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes exhibiting resistance to conventional cancer therapies (4). HIF is a heterodimer composed of a catalytic α subunit and a common β subunit (also known as ARNT). Whereas ARNT is constitutively expressed and stable, the α subunit (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α) is oxygen labile (3). Under normoxic conditions, HIF-α subunits are hydroxylated on conserved proline residues by a class of prolyl hydroxylases. The von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein is a substrate recognition component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets prolyl-hydroxylated HIF-α for ubiquitin-mediated destruction (22). Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-α remains unmodified by prolyl hydroxylases and thereby escapes recognition by VHL and destruction. The stable HIF-α dimerizes with ARNT to initiate the transcription of numerous hypoxia-inducible genes.

Germ line inheritance of a faulty VHL gene causes VHL disease, which is characterized by retinal and cerebellar hemangioblastomas, pheochromocytoma, and renal clear-cell carcinoma (RCC). Tumor development is associated with the loss of the remaining wild-type VHL allele in a susceptible cell. Biallelic inactivation of the VHL locus is also responsible for the development of the majority of sporadic RCC, establishing VHL as the critical “gatekeeper” of the renal epithelium (22). VHL contains two functional domains: α and β. The α domain is required for binding elongin C, which bridges VHL to the rest of the E3 ligase complex. The β domain functions as a protein-protein interaction interface and is necessary and sufficient for binding prolyl-hydroxylated HIF-α. Tumor-causing mutations frequently map to either domain, which results in the stabilization and accumulation of HIF-α, suggesting the importance of these domains in the tumor suppressor activity of VHL (37).

In addition to its role in promoting tumor growth, HIF-α has also been implicated in mediating diverse immune responses (12). For example, accumulation of HIF-α promotes the activity of NF-κB, a transcription factor that initiates multiple immune functions (2). Moreover, cytokines such as interleukin 1 beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and alpha interferon (IFN-α) can activate HIF in an oxygen-independent manner (10, 14). Recently, HIF was shown to be induced and activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of gram-negative bacterial cell walls (5). In a clinical context, the bacterial pathogen Bartonella henselae, which is known to cause vasculoproliferative disorders, also activates HIF under normoxic conditions (17). The evidence for the involvement of HIF in immunity is not limited to the observations that HIF is activated by pathogens and inflammatory mediators that are produced during immune responses. Oda et al. showed that HIF-1α is required for the maturation, activation, and effective infiltration of myeloid cells into sites of infection (27). Importantly, the loss of HIF-1α significantly impaired myeloid cells' ability to kill bacteria (8). In support, mice lacking HIF-1α in their myeloid cell lineage demonstrated reduced bactericidal activity and were unable to control the systemic spread of bacterial infection. The mechanism for this effect is likely due to the ability of HIF-1α to regulate the production of immune effector molecules, including granule proteases, antimicrobial peptides, nitric oxide, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (31). These findings demonstrate a role for HIF-α in mediating antibacterial responses in myeloid cells.

A diverse array of innate immune response mechanisms is initiated upon host cell recognition of conserved virus-associated molecular patterns, such as double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and single-stranded RNA. dsRNA is recognized by cellular receptors, including dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (20), Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), RIG-1, and Mda-5 (39). In contrast, single-stranded RNA is recognized by TLR7 and TLR8 (35). Upon recognition of these virus motifs, distinct signaling events are initiated in the host cell, resulting in the activation of specific transcription factors, such as NF-κB and IRF3 (35). These factors in turn mediate striking transcriptional changes within the host cell, including the upregulation of numerous cytokines, such as beta interferon (IFN-β), as well as chemokines and mediators of adaptive immune responses (33). The responses collaboratively function to limit virus replication, recruit immune cells to the site of infection, and direct subsequent adaptive immune responses.

IFNs comprise one family of cytokines that is commonly induced in host cells upon recognition of viral infection. They play key roles not only in promoting antiviral responses but also in mediating antiproliferative, immunoregulatory, and apoptotic activities. IFNs initiate autocrine and paracrine cellular signaling events by binding to their respective cell surface receptors, causing activation of the JAK/STAT pathway through specific phosphorylation and dimerization events. The STAT transcription factors then participate in upregulating the expression of numerous downstream IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). The antiviral mechanisms of some ISGs are well characterized. For example, in response to viral dsRNA, oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1) functions to limit virus replication by forming short 2′-5′ oligoadenylate strands, which in turn cause the enzyme RNase L to cleave both cellular and viral RNAs (24).

Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Rhabdoviridae family which causes cytolytic infections in mammals. It is highly sensitive to the antiviral effects of type 1 IFNs (36) and therefore has often been used as an ideal experimental model system to investigate the pathogenesis of virus infections and innate antiviral immunity (13). Here, we investigate the role of HIF-α in the antiviral response to VSV infection and show that VSV replication and cytolysis is dramatically inhibited by HIF-α activity. The 786-O (VHL−/−) RCC cells, which have constitutive HIF activity, are more resistant to the cytolytic effect of VSV than RCC cells expressing wild-type VHL with low basal HIF activity. Similarly, RCC cells expressing a disease-associated VHL(Y112H) mutant that is unable to down-regulate HIF-α are more resistant to VSV than RCC cells expressing another disease-associated VHL(L188V) mutant that nevertheless retain the ability to target HIF-α for degradation. Chetomin, a small-molecule inhibitor of HIF, sensitizes cells to VSV-mediated cytolysis. The antiviral activity of HIF is not restricted to RCC cells, since a hypoxia mimetic which stabilizes HIF-α concomitantly enhances the resistance of glioblastoma cells to VSV. Expression profiling experiments demonstrate that the presence of HIF-α appreciably heightens cellular responses to VSV infection by enhancing the inducibility of IFN-β and other transcripts with known functions in mediating the antiviral response. These results reveal a previously uncharacterized role of HIF-α in the cellular antiviral response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human 786-O RCC cells and 786-O subclones stably expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged wild-type VHL (786-VHL) or mutant VHL(L188V) were previously described (15, 18, 29, 30). A 786-O subclone stably expressing the VHL(Y112H) mutant was generated as described previously (15). 786-O cells stably expressing scrambled short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) or shRNA targeting HIF-2α were generously provided by William Kaelin (19). Human T98G glioblastoma cells and mouse L929 fibroblasts were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). All cells were cultured in antibiotic-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5%-CO2 atmosphere.

Antibodies.

Monoclonal anti-α-tubulin was obtained from Sigma (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Monoclonal anti-HA (12CA5) was obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Mannheim, Germany). Monoclonal anti-HIF-1α was obtained from NOVUS Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Monoclonal anti-VHL antibody was obtained from BD Pharmingen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Neutralizing mouse anti-human IFN-α/β receptor chain 2 (CD118) antibody was obtained from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (Piscataway, NJ).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblottting were performed as described previously (28).

Trypan blue cell viability assay.

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well (total volume, 2 ml) in six-well plates and incubated overnight in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were infected with VSV (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 0.1) obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 2 h postinfection, and DMEM with 10% FBS was replaced. They were then washed once with PBS at the indicated time point and were trypsinized and resuspended in trypan blue stain (0.4%) (Gibco-Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada). The number of live cells excluding the dye was determined under a light microscope using a hemocytometer. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Interferon protection assay.

786-O, 786-VHL, 786-Y112H, or 786-L188V cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and were incubated overnight at 37°C. They were treated with twofold serial dilutions of IFN-α2b, starting from 100 U/ml, and incubated for 18 h. The cells were then treated with VSV (MOI = 0.02) for 40 h in DMEM plus 0.5% FBS and stained with 0.5% crystal violet to visualize live cells.

Neutralizing antibody assays.

786-O and 786-VHL cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml of neutralizing anti-IFN-α/β receptor chain 2 antibody for 30 min prior to conducting a trypan blue cell viability assay or IFN protection assay.

Cobalt chloride antiviral assay.

T98G cells were plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate. They were incubated overnight at 37°C and then treated with 0.3 nM cobalt chloride in 10% FBS-DMEM for 16 h. The cells were subsequently challenged with twofold serial dilutions of VSV in DMEM plus 0.5% FBS and 0.3 nM cobalt chloride for 40 h and then stained with 0.5% crystal violet dye to visualize live cells.

Quantification of crystal violet-stained plates.

Cells stained with crystal violet were scanned using a SnapScan e50 (Afga) scanner, and the resulting TIFF images were imported into ImageJ (1). The images were converted to 8-bit gray scale, and the “integrated density” of each well was then measured. The “percentage of control” values were calculated by dividing the raw “integrated density” values by the “integrated density” of corresponding untreated control wells. Nonlinear regression was performed on the resulting values using a sigmoidal dose-response model with variable slope equation in GraphPad Prism version 4.0b for Mac (Mac 05 version) (GraphPad Software, San Diego CA).

Virus replication assay.

The virus replication assay was performed as previously described (9). 786-O or 786-VHL cells were plated in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and were incubated overnight in DMEM plus 10% FBS at 37°C. They were treated with VSV (MOI = 0.1) for 2 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS, and fresh DMEM plus 10% FBS medium was added. At the indicated time points, the cells were harvested and pooled with the supernatant. Cells were lysed by freeze-thaw and vortexing. Fivefold serial dilutions of the resulting lysates were added to L929 mouse fibroblast monolayers in 96-well plates and incubated for 48 h. Live cells were then stained with 0.5% crystal violet to quantify the median tissue culture infective dose.

Chetomin cell viability assay.

786-O or 786-VHL cells were plated in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight. They were then treated with 50 nM chetomin (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) for 18 h prior to RNA isolation for real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) or for 16 h prior to challenge with VSV (MOI = 0.1). Cell viability was quantified by trypan blue exclusion at 12-h intervals postinfection. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis.

RNA was isolated using the standard RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) protocol and treated with DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) for 30 min to remove residual DNA. RNA concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry, and 2.5 or 5 μg of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed by oligo(dT) priming. Reverse transcription was performed by incubating the RNA with 1 μl of 0.5-μg/μl oligo(dT) and DNase/RNase-free water (Sigma, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) to a total volume of 11 μl at 70°C for 10 min. Four microliters of 5× First Strand buffer, 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 1 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1 μl of SuperScript II enzyme (all from Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) were added to the reaction, and the mixture was incubated for 1.5 h at 42°C. The SuperScript was then inactivated by incubating the samples at 70°C for 15 min. These cDNA samples were stored at −20°C until used in real-time qPCR experiments.

Microarray and real-time semiquantitative PCR.

cDNA samples were derived from untreated 786-O and 786-VHL cells or 786-O and 786-VHL cells following VSV infection (MOI = 0.1) for 8 h in triplicate. The triplicate cDNA samples from the cells following the same treatment were pooled. Microarray analysis was performed using the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 array according to the manufacturer's protocol and analyzed using Microarray Analysis Suite 5.0 (MAS5.0) (Affymetrix Santa Clara, CA). Real-time qPCR reactions were run on 386-well plates in the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The real-time qPCR reaction mixture contains the following: 1 μl 10× PCR buffer, 0.6 μl 50 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μl deoxynucleoside triphosphates (10 mM [each] dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP), 0.2 μl primer mix, 0.025 μl Platinum Taq DNA polymerase, 0.3 μl SYBR Green I fluorescent dye, 0.2 μl ROX internal reference dye (all from Invitrogen), and 10 ng cDNA in a total volume of 10 μl. Real-time qPCR amplification conditions were as follows: 95°C (3 min); 40 cycles of 95°C (10 s), 65°C (15 s), 72°C (20 s); and 1 cycle of 60°C (15 s) and 95°C (15 s) for the dissociation curve. Genomic DNA derived from human placenta was used to generate standard curves for each primer tested. The housekeeping gene, β-ACTIN or TBP, was used to normalize cDNA loading. Gene-specific oligonucleotide primers designed using Primer Express 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were as follows: GLUT1 (5′-TGCAACGGCTTAGACTTCGA-3′ and 5′-GAGGACACTGATGAGAGGTACGTGTA-3′), EDN1 (5′-GCCCTCCAGAGAGCGTTATGT-3′ and 5′-CCCGAAGGTCTGTCACCAA-3′), IFNβ (5′-AGCAGTCTGCACCTGAAAAGATATT-3′ and 5′-TGTACTCCTTGGCCTTCAGGTAA-3′), IL6 (5′-CACTGGGCACAGAACTTATGTTG-3′ and 5′-AAAATAATTAAAATAGTGTCCTAACGCTCAT-3′), OAS-1 (5′-TGCTCCATATTTTACAGTCATTTTGG-3′ and 5′-GGACAAGGGATGTGAAAATTCC-3′), and IFIT1 (5′-AGGCATTAGATCTGGAAAGCTTGA-3′ and 5′-GCTTCATTCATATTTCCTTCCAATTT-3′).

RESULTS

HIF-1α was identified in microarray studies as being inducible by bacterial LPS and antiviral type I IFNs (10, 11). Therefore, we hypothesized that HIF-α not only is involved in mediating innate antibacterial responses but also participates in IFN-dependent antiviral responses.

Loss of VHL results in enhanced resistance to VSV.

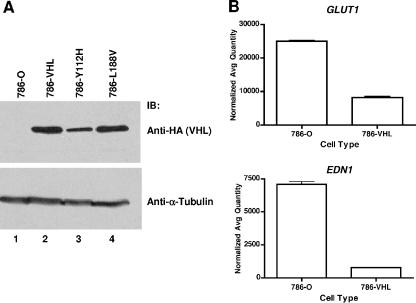

To test our hypothesis, we examined antiviral responses in 786-O cells, which are RCC cells devoid of functional VHL and which consequently overexpress HIF-α, as well as 786-O cells ectopically expressing HA-tagged VHL (786-VHL). VHL expression in the parental 786-O and 786-VHL cells was confirmed by anti-HA Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A). As expected, in comparison to 786-VHL cells, the parental cells expressed increased levels of HIF-responsive genes, such as GLUT1 and EDN1 (25), as measured by real-time semiquantitative PCR (Fig. 1B). 786-O and 786-VHL cells were treated with serial dilutions of IFN-α2b, followed by challenge with VSV at a MOI of 0.02. VSV effectively killed 786-VHL cells, and IFN treatment provided protection with an effective concentration (EC50) of 3.6 U/ml. Strikingly, 786-O cells were highly resistant to VSV-induced death even in the absence of IFN-α2b (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 1.

Generation of wild-type and mutant VHL-expressing 786-O RCC cells. (A) 786-O, 786-VHL, 786-Y112H, and 786-L188V cells were lysed, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody (top panel) or anti-α-tubulin antibody (bottom panel) as a loading control. (B) Steady-state mRNA levels of known HIF-α target genes, GLUT1 (top panel) and EDN1 (bottom panel), in 786-O (VHL−/−) or 786-VHL cells, were measured by real-time qPCR. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and error bars represent standard errors.

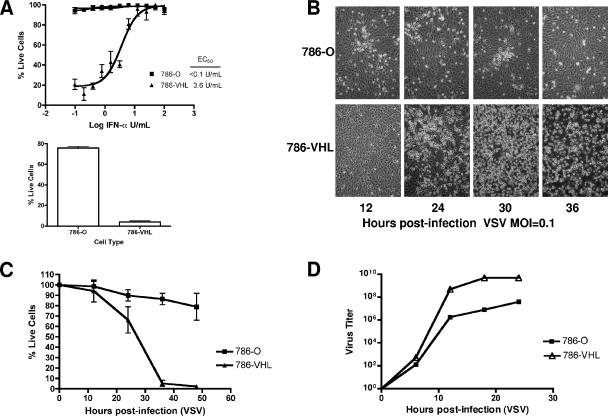

FIG. 2.

Loss of VHL results in enhanced resistance to VSV. (A) 786-O and 786-VHL cells were treated for 24 h with twofold serial dilutions of IFN-α-2b (starting from 100 U/ml) and then challenged with VSV (MOI = 0.02) for 40 h (top panel). 786-O and 786-VHL cells in the absence of IFN were challenged with VSV (MOI = 0.02) for 40 h (bottom panel). Live cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet and quantified by integrated density analysis. Nonlinear regression was performed, and EC50s were calculated in GraphPad Prism. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate, and error bars represent standard errors. (B) 786-O and 786-VHL cells were infected with VSV (MOI = 0.1) and visualized by phase-contrast microscopy at the indicated time points. (C) 786-O and 786-VHL cells were infected with VSV (MOI = 0.1), and viable cells were counted at 12-h intervals postinfection by trypan blue exclusion. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and error bars represent standard errors. (D) 786-O and 786-VHL cells were challenged with VSV (MOI = 0.1), and the cumulative virus titer was evaluated at 6-h intervals postinfection.

We next evaluated the cytolytic response to VSV infection by challenging 786-O and 786-VHL cells with wild-type VSV (MOI = 0.1). Live cells were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy and quantified by trypan blue exclusion postinfection. 786-VHL cells were significantly more sensitive to cytolysis than the 786-O cells (Fig. 2B and C). Whereas VSV killed nearly 100% of the 786-VHL cells by 48 h postinfection, 786-O cells were marginally affected (Fig. 2C). The level of cytotoxicity was further validated by crystal violet staining and immunoblotting for PARP cleavage (data not shown). The enhanced antiviral resistance observed in 786-O cells was corroborated by restricted virus replication in comparison to VHL-expressing counterpart (Fig. 2D). At 24 h postinfection, there was approximately a 2-log difference in the VSV titer, with a titer of 5.01 × 109 in 786-VHL cells and 3.98 × 107 in 786-O cells (Fig. 2D).

The enhanced antiviral activity of RCC cells is HIF dependent.

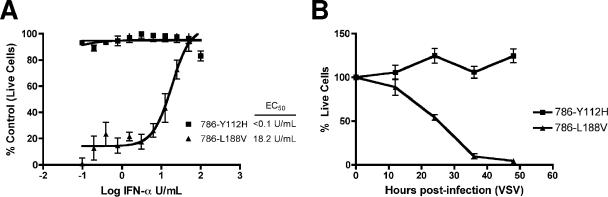

The negative regulation of HIF via ubiquitin-mediated destruction is the best-characterized function of VHL. Therefore, we next asked whether the observed resistance of VHL-null RCC cells to VSV is HIF dependent. The VHL(L188V) mutant is associated with type 2C VHL disease, which is characterized by the exclusive development of pheochromocytoma without the other stigmata of the disease (28). It is well documented that VHL(L188V) retains the ability to properly regulate HIF (15), suggesting a HIF-independent function of VHL that is critical for the development of pheochromocytoma. The VHL(Y112H) mutant is associated with type 2A VHL disease, which is characterized by the development of retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas, as well as RCC. Like most VHL mutants tested to date, VHL(Y112H) has an impaired ability to regulate HIF due to its inability to bind prolyl-hydroxylated HIF-α (6). RCC cells ectopically expressing VHL(Y112H) (786-Y112H) (Fig. 1A), like the VHL-null 786-O cells, were resistant to VSV-mediated killing even under the lowest-dose IFN-α treatment (Fig. 3A). In contrast, 786-L188V cells (see Fig. 1A) were sensitive to VSV infection and required higher does of IFN for protection (Fig. 3A). In addition, 786-L188V cells were significantly more sensitive to the cytolytic effect of VSV than 786-Y112H cells (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

RCC cells expressing a VHL mutant with defective HIF-regulatory function show resistance to VSV. (A) 786-Y112H and 786-L188V cells were treated for 24 h with twofold serial dilutions of IFN-α-2b (starting from 100 U/ml) and then challenged with VSV (MOI = 0.02) for 40 h. Live cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet and quantified by integrated density analysis. Nonlinear regression was performed, and the EC50 was calculated in GraphPad Prism. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate, and error bars represent standard errors. (B) VHL-Y112H and VHL-L188V cells were infected with VSV (MOI = 0.1), and viable cells were counted at 12-h intervals postinfection by trypan blue exclusion. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and error bars represent standard errors.

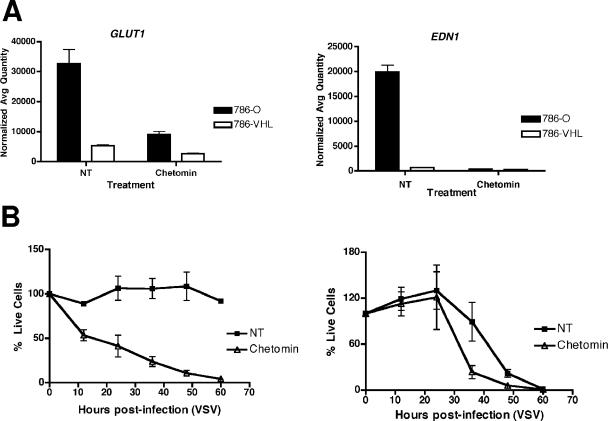

In a complementary experiment, pretreatment with chetomin, a small-molecule inhibitor of HIF-α activity (21), had a negligible effect on the response of 786-VHL cells to VSV (Fig. 4B, right panel) but dramatically enhanced the cytolytic effect of VSV on 786-O cells (Fig. 4B, left panel). Notably, the effect of chetomin on HIF target genes, GLUT1 and EDN1, was confirmed by real-time qPCR (Fig. 4A). In addition, 786-O subclones (shHIF-2α-2 and shHIF-2α-9) stably expressing shRNAs targeting HIF-2α were markedly more sensitive to VSV than cells expressing scrambled shRNA (Fig. 5B). Real-time qPCR experiments confirmed the effective knockdown of HIF-2α in 786-O cells expressing shHIF-2α (Fig. 5A). These results, taken together, suggest that VHL-mediated regulation of HIF is critical for the enhanced antiviral effect of RCC against VSV.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of HIF activity using a small-molecule inhibitor, chetomin, sensitizes RCC cells to VSV. (A) 786-O and 786-VHL cells were treated for 18 h with 50 nM chetomin, and steady-state mRNA levels of HIF-α target genes, GLUT1 (left panel) and EDN1 (right panel), were measured by real-time qPCR. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and error bars represent standard errors. (B) 786-O cells (left panel) and 786-VHL cells (right panel) were treated with 50 nM chetomin for 16 h and then challenged with VSV (MOI = 0.1). Live cells were counted at 12-h intervals by trypan blue exclusion. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and error bars represent standard errors.

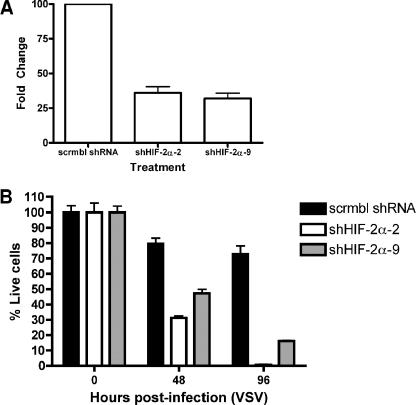

FIG. 5.

Reduction of HIF-2α levels by RNA interference sensitizes RCC cells to VSV. (A) The steady-state mRNA levels of HIF-2α were measured by real-time qPCR in 786-O cells expressing control scrambled shRNA (scrmbl shRNA) or shRNA targeting HIF-2α (786-O subclones: shHIF-2α-2 and shHIF-2α-9). (B) Scrmbl shRNA-, shHIF-2α (clone 2)-, and shHIF-2α (clone 9)-expressing cells were infected with VSV (MOI = 0.1) for the indicated time points. Live cells were quantified by trypan blue exclusion.

HIF confers protection against VSV-induced cytotoxicity of glioblastoma cells.

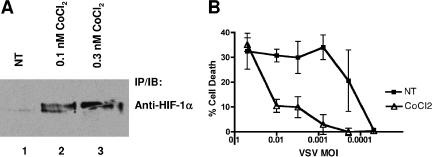

To ascertain whether the activation of HIF-α can confer protection on VSV-induced cell death in non-RCC cancer cells, we investigated the antiviral response of the glioblastoma cell line T98G. Treatment of T98G cells with a hypoxia-mimetic CoCl2 induced the accumulation of HIF-1α as expected (Fig. 6A) and appreciably protected the T98G cells against increasing doses of VSV (Fig. 6B). This result suggests that HIF may be a general mediator of the antiviral response to VSV.

FIG. 6.

HIF activity confers protection on VSV in T98G glioblastoma cells. (A) T98G cells were treated with CoCl2 for 16 h and lysed. Protein concentrations of cell lysates were measured by Bradford assay, and equal amounts of cellular extracts were immunoprecipitated with an excess of anti-HIF-1α antibody. Bound proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by anti-HIF-1a immunoblotting. (B) T98G cells were treated for 16 h with 0.3 nM cobalt chloride and then challenged with serial dilutions of VSV for 40 h. Live cells were stained with crystal violet and quantified by integrated density analysis. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate, and error bars represent standard errors.

HIF enhances the induction of genes with “immune response” functions by VSV.

To identify potential downstream effector genes regulated by HIF in response to VSV infection, we conducted Affymetrix microarray experiments using 786-O and 786-VHL cells 8 h post-VSV infection. Previous experiments have shown that a number of NF-κB-dependent genes showed maximal induction in 786-O cells at this time point (data not shown). The results of the microarray experiments were analyzed using MAS 5.0, and the probe sets exhibiting the greatest degrees of change in 786-O and 786-VHL cells are listed in Table 1. Interestingly, IFNβ was identified as the gene exhibiting the highest level of induction by VSV infection, and it showed a markedly higher degree of change in 786-O cells (73.52-fold) than in 786-VHL cells (22.63-fold). In addition, numerous ISGs, including ISG20, IFIT2, OAS1, and IFIT3, showed higher levels of change in 786-O cells than in 786-VHL cells, indicating a stronger IFN/antiviral response in cells that overexpress HIF in the absence of VHL.

TABLE 1.

Genes demonstrating the greatest n-fold changes after VSV treatment in 786-O and 786-VHL cells were identified by Affymetrix microarray analysis

| Affymetrix probe | Gene name | Description of gene product | Fold change (VSV 8 h)a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 786-O | 786-VHL | |||

| 208173_at | IFNB1 | Interferon, beta 1, fibroblast | 73.52 | 22.63 |

| 204698_at | ISG20 | Interferon-stimulated exonuclease, 20 kDa | 24.25 | 1.07 |

| 226757_at | IFIT2 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | 22.63 | 6.50 |

| 242625_at | RSAD2 | Radical S-adenosyl methionine domain containing 2 | 19.70 | 2.14 |

| 241060_x_at | TM4SF9 | Tetraspanin 5 | 18.38 | 2.00 |

| 237911_at | Transcribed locus | 17.15 | 6.96 | |

| 204533_at | CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | 17.15 | 2.64 |

| 205552_s_at | OAS1 | 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase 1, 40/46 kDa | 17.15 | -1.23 |

| 208392_x_at | SP110 | SP110 nuclear body protein | 16.00 | 3.25 |

| 213797_at | RSAD2 | Radical S-adenosyl methionine domain containing 2 | 16.00 | 2.14 |

| 204747_at | IFIT3 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 | 14.93 | 8.57 |

| 226702_at | LOC129607 | Hypothetical protein LOC129607 | 14.93 | 8.57 |

| 203153_at | IFIT1 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 14.93 | 5.66 |

| 211122_s_at | CXCL11 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | 13.93 | 14.93 |

| 238725_at | Transcribed locus, weakly similar to XP_496299.1 | 13.93 | 5.28 | |

| 202869_at | OAS1 | 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase 1, 40/46 kDa | 13.93 | 3.48 |

| 235643_at | SAMD9L | Sterile alpha motif domain containing 9 like | 13.00 | 4.29 |

| 202269_x_at | GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1, interferon inducible, 67 kDa | 13.00 | 2.64 |

| 202270_at | GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1, interferon inducible, 67 kDa | 13.00 | 2.46 |

| 218943_s_at | DDX58 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 58 | 13.00 | -1.15 |

| 231577_s_at | GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1, interferon-inducible, 67 kDa | 12.13 | 6.96 |

| 210797_s_at | OASL | 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase like | 12.13 | 5.28 |

| 219209_at | IFIH1 | Interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 | 12.13 | 2.30 |

n-fold change in gene expression 8 h post-VSV infection.

In a complementary analysis to objectively evaluate the biological functions of the genes preferentially induced by VSV infection in 786-O cells, gene ontology (GO biological process) and Swiss-Prot (biological process and molecular function) annotations of the genes that showed at least twofold-greater induction by VSV in 786-O cells than in the 786-VHL counterpart (total of 121 genes) were analyzed using EASE (16). The results, as summarized in Table 2, clearly demonstrate a strong enrichment of genes involved in the immune and defense response, including the cellular response to virus. Moreover, the Swiss-Prot Biological Process and Molecular Function categories notably indicate overrepresentation of cytokines (for example, CXCl10, IL7, IFNβ, CXCl11, and TNFSF13B) and of genes involved in interferon induction, peptide transport, and transcriptional regulation (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

HIF enhances induction of genes with “immune response” functions by VSVa

| Category | No. of genes on list | No. of genes on array | EASE score | Result, Fisher's exact test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOb biological process | ||||

| Defense response | 28 | 815 | 1.46E-13 | 2.49E-14 |

| Immune response | 26 | 725 | 5.90E-13 | 9.66E-14 |

| Response to pest/pathogen/parasite | 13 | 465 | 2.17E-05 | 4.54E-06 |

| Response to virus | 4 | 33 | 1.01E-03 | 4.57E-05 |

| Innate immune response | 6 | 193 | 6.15E-03 | 1.14E-03 |

| Response to stress | 13 | 824 | 3.78E-03 | 1.40E-03 |

| Response to wounding | 7 | 278 | 6.60E-03 | 1.52E-03 |

| Inflammatory response | 5 | 180 | 2.32E-02 | 4.80E-03 |

| Swiss-Prot biological process/molecular function | ||||

| Interferon induction | 13 | 33 | 1.10E-19 | 1.06E-21 |

| Peptide transport | 2 | 5 | 2.87E-02 | 3.40E-04 |

| Cytokine | 5 | 147 | 1.02E-02 | 1.68E-03 |

| Transcription regulation | 11 | 921 | 3.61E-02 | 1.69E-02 |

Gene enrichment analysis using EASE. EASE analysis of probe sets that are preferentially induced in 786-O cells compared to induction in 786-VHL cells shows enrichment of genes involved in the immune, defense, and interferon responses.

GO, gene ontology.

TABLE 3.

HIF enhances induction of genes with “immune response” functions by VSVa

| Category and Affymetrix probe | Gene name | Description of gene product |

|---|---|---|

| Interferon induction | ||

| 202269_X_AT | GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1, interferon inducible, 67 kDa |

| 202270_AT | GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1, interferon inducible, 67 kDa |

| 202531_AT | IRF1 | Interferon regulatory factor 1 |

| 202748_AT | GBP2 | Guanylate binding protein 2, interferon inducible |

| 203275_AT | IRF2 | Interferon regulatory factor 2 |

| 204502_AT | SAMHD1 | SAM domain and HD domain 1 |

| 204533_AT | CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 |

| 204747_AT | IFIT4 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 4 |

| 204972_AT | OAS2 | 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase 2, 69/71 kDa |

| 204994_AT | MX2 | Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 (mouse) |

| 205552_S_AT | OAS1 | 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase 1, 40/46 kDa |

| 205660_AT | OASL | 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase like |

| 208966_X_AT | IFI16 | Interferon, gamma-inducible protein 16 |

| 210797_S_AT | OASL | 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase like |

| 214022_S_AT | IFITM1 | Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1 (9-27) |

| 231577_S_AT | GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1, interferon inducible, 67 kDa |

| 234987_AT | SAMHD1 | SAM domain and HD domain 1 |

| 235529_X_AT | SAMHD1 | SAM domain and HD domain 1 |

| Peptide transport | ||

| 202307_S_AT | TAP1 | Transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, subfamily B (MDR/TAP) |

| 225973_AT | TAP2 | Transporter 2, ATP-binding cassette, subfamily B (MDR/TAP) |

| Cytokine | ||

| 204533_AT | CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 |

| 206693_AT | IL-7 | Interleukin 7 |

| 208173_AT | IFNB1 | Interferon, beta 1, fibroblast |

| 211122_S_AT | CXCL11 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 |

| 223501_AT | TNFSF13B | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 13b |

| 223502_S_AT | TNFSF13B | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 13b |

| Transcription regulation | ||

| 202531_AT | IRF1 | Interferon regulatory factor 1 |

| 202672_S_AT | ATF3 | Activating transcription factor 3 |

| 203275_AT | IRF2 | Interferon regulatory factor 2 |

| 205659_AT | HDAC9 | Histone deacetylase 9 |

| 205739_X_AT | ZFD25 | Zinc finger protein (ZFD25) |

| 206503_X_AT | PML | Promyelocytic leukemia |

| 208436_S_AT | IRF7 | Interferon regulatory factor 7 |

| 208966_X_AT | IFI16 | Interferon, gamma-inducible protein 16 |

| 211012_S_AT | PML | Promyelocytic leukemia |

| 211013_X_AT | PML | Promyelocytic leukemia |

| 220266_S_AT | KLF4 | Kruppel-like factor 4 (gut) |

| 227400_AT | NFIX | Nuclear factor I/X (CCAAT-binding transcription factor) |

| 228230_AT | PRIC285 | Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor A interacting complex 285 |

Specific genes within Swiss-Prot categories were identified by EASE analysis as being preferentially induced in 786-O cells compared to induction in 786-VHL cells. MDR/TAP, multidrug resistance transporters.

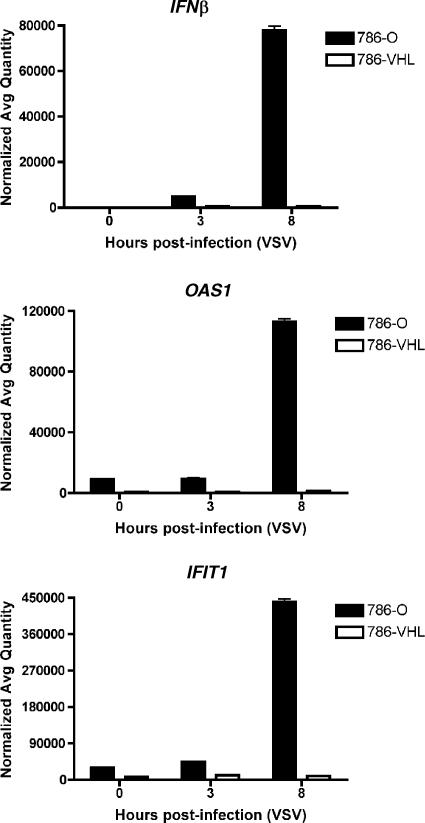

The preferential induction of several ISGs (IFNβ, OAS1, and IFIT1) observed in the microarray experiment as showing the greatest degrees of change after VSV treatment was validated by real-time qPCR. 786-O and 786-VHL cells displayed similarly low levels of these genes in the absence of VSV infection and at 3 h postinfection (Fig. 7). However, there was a dramatic induction of these genes in 786-O cells by 8 h post-VSV infection in comparison to levels in 786-VHL cells (Fig. 7). Importantly, both IFNβ and OAS1 have well-characterized antiviral functions (32).

FIG. 7.

HIF enhances the induction of IFN-β and ISGs by VSV. 786-O and 786-VHL cells were infected with VSV (MOI = 0.1) for 3 or 8 h. Steady-state mRNA levels of IFNβ (top panel), OAS1 (middle panel), and IFIT1 (bottom panel) were measured by real-time qPCR. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and error bars represent standard errors.

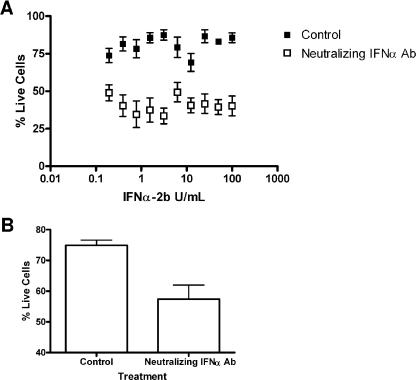

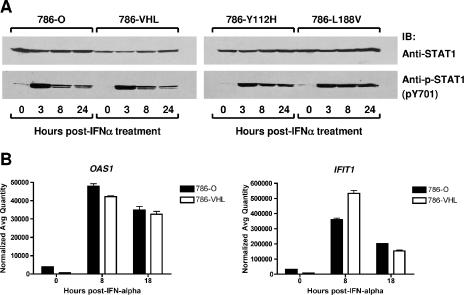

The functional involvement of IFN in the observed antiviral responses was confirmed by experiments using neutralizing antibody targeting IFN-α/β receptor chain 2 (CD118). The neutralizing antibody sensitized 786-O cells to VSV in IFN protection assays at all doses of IFN-α2b evaluated (Fig. 8A). Consistently, the neutralizing antibody enhanced the sensitivity of 786-O cells to the cytolytic effect of VSV even in the absence of IFN pretreatment (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that the protection against VSV-mediated killing observed in 786-O cells was due, at least in part, to IFN. Moreover, the sensitivity of 786-VHL cells in the presence of neutralizing antibody modestly increased the sensitivity to VSV as well (data not shown). Notably, while HIF enhances IFN production, it does not appear to affect cellular responses to exogenous IFN treatment (Fig. 9). Specifically, the activation of STAT1 (as measured by Y701 phosphorylation) (Fig. 9A) and the induction of ISGs (including IFIT1 and OAS1) in response to IFN-α treatment (Fig. 9B) were comparable in 786-O and 786-VHL cells. These results, taken together, suggest that the ability of RCC cells to respond to IFN is likely not affected by the status of VHL or HIF, but rather the induction of IFN upon viral infection is enhanced by the activity of HIF.

FIG. 8.

Neutralizing anti-IFN-α/β receptor antibody enhances the sensitivity of 786-O cells to VSV. (A) 786-O cells were treated with neutralizing anti-IFN-α antibody for 30 min, followed by twofold serial dilutions of IFN-α-2b (starting from 100 U/ml) for 24 h. The cells were then challenged with VSV (MOI = 0.02) for 40 h. Live cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet and quantified by integrated density analysis. Nonlinear regression was performed in GraphPad Prism. Experiments were performed in octuplicate, and error bars represent standard errors. (B) 786-O and 786-VHL cells were treated with neutralizing anti-IFN-α/β receptor antibody in the absence of IFN-α-2b and challenged with VSV (MOI = 0.02) for 40 h. Live cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet and quantified by integrated density analysis. Experiments were performed in octuplicate, and error bars represent standard errors.

FIG. 9.

The ability of RCC cells to respond to exogenous IFN treatment is independent of VHL status. (A) 786-O, 786-VHL, 786-Y112H, and 786-L188V cells were treated with 50 U/ml IFN-α-2b for 3, 8, or 24 h. Cells were then lysed, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and immunoblotted with anti-STAT1 (top panel) or anti-phospho-STAT1 (pY701-STAT1) (bottom panel) antibody. (B) 786-O and 786-VHL cells were treated with 50 U/ml IFN-α-2b for 8 and 18 h, and then steady-state mRNA levels of OAS1 (left panel) and IFIT1 (right panel) were measured by real-time qPCR. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and error bars represent standard errors.

DISCUSSION

HIF has been best studied for its role as a primary mediator of cellular responses to hypoxia. Pathological activation of HIF-α is observed in many forms of cancer and is recognized as being prognostic for a poor clinical outcome. HIF-α-regulated genes have been implicated in promoting tumor progression and metastasis by enhancing angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and the resistance to apoptotic cell death (23). Emerging evidence, however, suggests additional roles for HIF-α in host immune functions (12). For example, HIF-α can be activated by a number of different cytokines, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, including LPS, or by infection with certain bacteria (31). In addition, HIF-α has been shown to be activated upon infection with hepatitis B virus (41) and Epstein-Barr virus (38). However, the impact of HIF-α activity on host cell responses to viruses had not been well studied.

Here, we have demonstrated that the loss of VHL enhances antiviral protection against VSV-induced cell death through a HIF-α-dependent mechanism. 786-O cells, which are devoid of functional VHL, are more resistant to VSV than 786-VHL cells. Moreover, 786-Y112H cells, which express a mutant VHL with an impaired ability to target prolyl-hydroxylated HIF-α, is similarly more resistant to VSV than 786-L188V cells, which express a mutant VHL that retains its ability to regulate HIF. The observation that chetomin, a small molecule inhibitor of HIF activity, increases the sensitivity of 786-O cells to VSV infection provides further support for the notion that HIF plays a critical role in the enhancement of the antiviral response. This was further confirmed by the increased susceptibility to VSV observed upon targeting of HIF-2α by RNA interference. Consistently, cobalt chloride, which stabilizes HIF-α, promotes resistance against VSV-induced cytotoxicity in T98G glioblastoma cells.

In contrast to our findings demonstrating HIF-enhanced cellular resistance to VSV, Connor et al. showed that the virus replicated similarly under both hypoxic and normoxic conditions, although VSV replication was delayed in hypoxic tumor cells (7). This would suggest that the expression of HIF does not correlate with viral replication. However, there are key differences between the study by Connor et al. and the present study. Whereas a low MOI of 0.1 for VSV was used in our experiments, the majority of the experiments by Connor et al. were conducted using a relatively high MOI of 10. Indeed, HeLa cells produced comparable virus titers irrespective of oxygen tension when challenged with VSV at an MOI of 10 (7). However, and consistent with our data, at a low MOI of 0.01, hypoxia significantly reduced the virus titer by 1 log (7). It is likely that a high dose of virus could overwhelm any antiviral effect mediated by HIF. Furthermore, the present study strictly addresses the role of HIF in the antiviral response, while Conner et al. examined the effect of hypoxia on the cytopathic effect and replication of VSV. It is reasonable to consider the possibility of other, yet-undefined factors induced during hypoxia that may have “masked” the effect of HIF.

The microarray and real-time qPCR analyses made in our study demonstrate that upon VSV infection, constitutive HIF activity results in significantly upregulated expression of genes with functional roles in the immune/defense response, including IFNβ, OAS1, and IFIT1. The notion that HIF induces an antiviral response is supported by Naldini and colleagues, who observed that hypoxic conditions reduced the cytopathogenicity of VSV and increased the antiviral effects of IFNs (26). Notably, we observed that the ability of cells to respond to exogenous IFN treatment is not influenced by HIF status. Neither STAT1 Y701 phosphorylation nor the induction of ISGs by IFN-α treatment differed between 786-O and 786-VHL cells (Fig. 9). Accordingly, An and Rettig recently reported that IFN activation of STAT1 phosphorylation in 786-O cells was unaffected by VHL status (2). In light of these observations, our findings strongly suggest that while HIF affects cellular responses to VSV, including VSV-induced IFN expression, it does not alter the cellular response to exogenous IFN-α. Furthermore, since 786-O and 786-VHL cells showed intact and comparable responses to exogenous IFN, the enhanced expression of the numerous ISGs observed in 786-O cells is likely due to IFN feedback signaling resulting from the preferential induction of IFNβ.

Many of the immune response genes identified in our study are transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB. For example, IFNβ, which was the most highly up-regulated gene transcript observed, is recognized as an NF-κB-responsive gene (40). Correspondingly, HIF has been shown to promote the activity of NF-κB (2). However, our results demonstrate that HIF activity alone is insufficient to trigger NF-κB-mediated activation of an IFN response, since in the absence of VSV infection, the expression levels of these genes were comparably low in both 786-O and 786-VHL cells. Only upon VSV infection were the levels of genes with known antiviral function dramatically upregulated in 786-O cells. In support of this notion, IFNβ induction requires the transcription factor IRF3 in addition to NF-κB (34). Thus, VSV infection may activate additional transcription factor(s) that work in concert with HIF to trigger the antiviral response. The findings that neutralizing antibody to IFN-α enhanced cellular sensitivity to VSV indicate that IFN production played a functional role in the antiviral state observed in 786-O cells.

Collectively, our findings demonstrate a novel role for HIF as a modulator of the host cell innate immune response to virus infection via the enhancement of IFN and other gene transcripts involved in mediating the antiviral response. Our findings support a basis for investigating the application of modulators, specifically inducers, of HIF signaling as potential antiviral therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Cancer Institute of Canada. I.I.L.H. is a recipient of the Ontario Graduate scholarship. M.O. is a Canada Research Chair in molecular oncology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 August 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramoff, M., P. Magelhaes, and S. Ram. 2004. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 11:36-42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.An, J., and M. B. Rettig. 2005. Mechanism of von Hippel-Lindau protein-mediated suppression of nuclear factor kappa B activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:7546-7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacon, A. L., and A. L. Harris. 2004. Hypoxia-inducible factors and hypoxic cell death in tumour physiology. Ann. Med. 36:530-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardos, J. I., and M. Ashcroft. 2004. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and oncogenic signalling. Bioessays 26:262-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blouin, C. C., E. L. Page, G. M. Soucy, and D. E. Richard. 2004. Hypoxic gene activation by lipopolysaccharide in macrophages: implication of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Blood 103:1124-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cockman, M. E., N. Masson, D. R. Mole, P. Jaakkola, G. W. Chang, S. C. Clifford, E. R. Maher, C. W. Pugh, P. J. Ratcliffe, and P. H. Maxwell. 2000. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25733-25741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connor, J. H., C. Naczki, C. Koumenis, and D. S. Lyles. 2004. Replication and cytopathic effect of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus in hypoxic tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 78:8960-8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer, T., Y. Yamanishi, B. E. Clausen, I. Forster, R. Pawlinski, N. Mackman, V. H. Haase, R. Jaenisch, M. Corr, V. Nizet, G. S. Firestein, H. P. Gerber, N. Ferrara, and R. S. Johnson. 2003. HIF-1α is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell 112:645-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Der, S. D., and A. S. Lau. 1995. Involvement of the double-stranded-RNA-dependent kinase PKR in interferon expression and interferon-mediated antiviral activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8841-8845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Der, S. D., A. Zhou, B. R. Williams, and R. H. Silverman. 1998. Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15623-15628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Veer, M. J., M. Holko, M. Frevel, E. Walker, S. Der, J. M. Paranjape, R. H. Silverman, and B. R. Williams. 2001. Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69:912-920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddad, J. J., and H. L. Harb. 2005. Cytokines and the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α. Int. Immunopharmacol. 5:461-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hangartner, L., R. M. Zinkernagel, and H. Hengartner. 2006. Antiviral antibody responses: the two extremes of a wide spectrum. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6:231-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellwig-Burgel, T., D. P. Stiehl, A. E. Wagner, E. Metzen, and W. Jelkmann. 2005. Review: hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1): a novel transcription factor in immune reactions. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25:297-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman, M. A., M. Ohh, H. Yang, J. M. Klco, M. Ivan, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 2001. von Hippel-Lindau protein mutants linked to type 2C VHL disease preserve the ability to downregulate HIF. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:1019-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosack, D. A., G. Dennis, Jr., B. T. Sherman, H. C. Lane, and R. A. Lempicki. 2003. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 4:R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempf, V. A., M. Lebiedziejewski, K. Alitalo, J. H. Walzlein, U. Ehehalt, J. Fiebig, S. Huber, B. Schutt, C. A. Sander, S. Muller, G. Grassl, A. S. Yazdi, B. Brehm, and I. B. Autenrieth. 2005. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in bacillary angiomatosis: evidence for a role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in bacterial infections. Circulation 111:1054-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kibel, A., O. Iliopoulos, J. A. DeCaprio, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 1995. Binding of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein to Elongin B and C. Science 269:1444-1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo, A., W. Y. Kim, M. Lechpammer, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 2003. Inhibition of HIF2α is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol. 1:439-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar, A., Y. L. Yang, V. Flati, S. Der, S. Kadereit, A. Deb, J. Haque, L. Reis, C. Weissmann, and B. R. Williams. 1997. Deficient cytokine signaling in mouse embryo fibroblasts with a targeted deletion in the PKR gene: role of IRF-1 and NF-κB. EMBO J. 16:406-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kung, A. L., S. D. Zabludoff, D. S. France, S. J. Freedman, E. A. Tanner, A. Vieira, S. Cornell-Kennon, J. Lee, B. Wang, J. Wang, K. Memmert, H. U. Naegeli, F. Petersen, M. J. Eck, K. W. Bair, A. W. Wood, and D. M. Livingston. 2004. Small molecule blockade of transcriptional coactivation of the hypoxia-inducible factor pathway. Cancer Cell 6:33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung, S. K., and M. Ohh. 2002. Playing tag with HIF: the VHL story. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2:131-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, L., and M. C. Simon. 2004. Regulation of transcription and translation by hypoxia. Cancer Biol. Ther. 3:492-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malathi, K., J. M. Paranjape, E. Bulanova, M. Shim, J. M. Guenther-Johnson, P. W. Faber, T. E. Eling, B. R. Williams, and R. H. Silverman. 2005. A transcriptional signaling pathway in the IFN system mediated by 2′-5′-oligoadenylate activation of RNase L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:14533-14538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maynard, M. A., and M. Ohh. 2004. Von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and hypoxia-inducible factor in kidney cancer. Am. J. Nephrol. 24:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naldini, A., F. Carraro, W. R. Fleischmann, Jr., and V. Bocci. 1993. Hypoxia enhances the antiviral activity of interferons. J. Interferon Res. 13:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oda, T., K. Hirota, K. Nishi, S. Takabuchi, S. Oda, H. Yamada, T. Arai, K. Fukuda, T. Kita, T. Adachi, G. L. Semenza, and R. Nohara. 2006. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 during macrophage differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291:C104-C13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohh, M., W. Y. Kim, J. J. Moslehi, Y. Chen, V. Chau, M. A. Read, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 2002. An intact NEDD8 pathway is required for Cullin-dependent ubiquitylation in mammalian cells. EMBO Rep 3:177-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohh, M., Y. Takagi, T. Aso, C. E. Stebbins, N. P. Pavletich, B. Zbar, R. C. Conaway, J. W. Conaway, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 1999. Synthetic peptides define critical contacts between elongin C, elongin B, and the von Hippel-Lindau protein. J. Clin. Investig. 104:1583-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohh, M., R. L. Yauch, K. M. Lonergan, J. M. Whaley, A. O. Stemmer-Rachamimov, D. N. Louis, B. J. Gavin, N. Kley, W. G. Kaelin, Jr., and O. Iliopoulos. 1998. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein is required for proper assembly of an extracellular fibronectin matrix. Mol. Cell 1:959-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peyssonnaux, C., V. Datta, T. Cramer, A. Doedens, E. A. Theodorakis, R. L. Gallo, N. Hurtado-Ziola, V. Nizet, and R. S. Johnson. 2005. HIF-1α expression regulates the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 115:1806-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuel, C. E. 2001. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:778-809, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroder, M., and A. G. Bowie. 2005. TLR3 in antiviral immunity: key player or bystander? Trends Immunol. 26:462-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sen, G. C., and S. N. Sarkar. 2005. Transcriptional signaling by double-stranded RNA: role of TLR3. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seth, R. B., L. Sun, and Z. J. Chen. 2006. Antiviral innate immunity pathways. Cell Res. 16:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinozaki, K., O. Ebert, A. Suriawinata, S. N. Thung, and S. L. Woo. 2005. Prophylactic alpha interferon treatment increases the therapeutic index of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus virotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in immune-competent rats. J. Virol. 79:13705-13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sufan, R. I., M. A. Jewett, and M. Ohh. 2004. The role of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and hypoxia in renal clear cell carcinoma. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 287:F1-F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakisaka, N., S. Kondo, T. Yoshizaki, S. Murono, M. Furukawa, and J. S. Pagano. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces synthesis of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:5223-5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werts, C., S. E. Girardin, and D. J. Philpott. 2006. TIR, CARD and PYRIN: three domains for an antimicrobial triad. Cell Death Differ. 13:798-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yie, J., M. Merika, N. Munshi, G. Chen, and D. Thanos. 1999. The role of HMG I(Y) in the assembly and function of the IFN-beta enhanceosome. EMBO J. 18:3074-3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo, Y. G., S. Cho, S. Park, and M. O. Lee. 2004. The carboxy-terminus of the hepatitis B virus X protein is necessary and sufficient for the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. FEBS Lett. 577:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]