Abstract

We report the complete sequence analysis of the provirus harbored in a long-term nonprogressor (patient SG1) 20 years after the first infection with a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strain lacking nef. The sequencing showed large deletions in the nef-nef and nef-U3 regions. Except for vpu, all of the other accessory genes were intact. The gag and pol genes did not show significant alterations. We found large deletions in env, spanning the V1, V2, V3, V4, and V5 regions. We believe that, when down-regulation of the class 1 major histocompatibility complex molecules is inhibited by the lack of nef function, the cells containing Env-defective molecules evade cytotoxic T lymphocyte killing and accumulate progressively.

Pioneer studies of Desrosiers et al. clearly indicated that the genetic alterations of nef reduce the replication capacity and the pathogenicity of simian immunodeficiency viruses (4, 6, 7). In humans, the nef gene could play a crucial role in the progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. In fact, all patients harboring viruses containing deletions in this gene belonged to the long-term nonprogressor (LTNP) category (3, 8, 9, 14). Also, some minor genetic defects of nef have been related to the LTNP status of HIV-1-infected patients (1, 12, 13).

The largest investigation concerning viruses lacking nef and LTNP status was performed with the Sydney Blood Bank Cohort. The members of this cohort received an HIV-1 strain lacking nef from a single donor via blood transfusion. All of these subjects were long-term nonprogressors and have been followed up for many years (2, 10). The LTNP status of these individuals did not appear to be stable since two of them showed, with time, slight signs of clinical progression and began antiretroviral therapy. The loss of LTNP status in these patients occurred without the apparent emergence of nef revertant viruses (2).

In the present study, we report the further evolution of the clinical and virological findings of an LTNP patient, designated SG1, who in 1996 was found to be infected with a virus containing large deletions in the nef gene (14). Patient SG1, a 43-year-old homosexual male, has been HIV-1 seropositive since 1985. He never received antiretroviral therapy. The patient has always been asymptomatic, with constant levels of CD4+ cells of around 1,000 cells/mm3 and extremely low (around 200 copies/ml) or undetectable viral load in plasma.

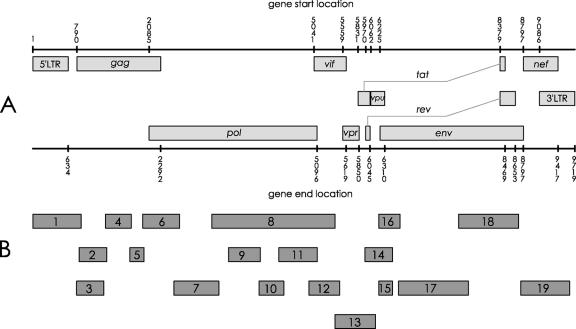

The entire genome of the provirus harbored in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of SG1 during 2005 has been sequenced. Nineteen nested amplifications covered the entire map of the HIV-1 provirus (Fig. 1). DNA was extracted both from PBMCs of SG1 and from the 8e5LAV control cell line by use of a QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (QIAGEN). PCRs were carried out with 200 ng to 1 μg of DNA template in a 50-μl PCR mixture containing 40 pmol of each primer, Taq Gold 1× buffer (Applera), 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1.5 to 2 U of Taq Gold. DNA from 8e5LAV cells was processed in the same way. The first-round PCR was performed at annealing temperatures of nearly 60°C to ensure stringent amplifications. One to five microliters of amplified product from the first-round PCR was used as a template for the second round.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of the entire HIV-1 genome in PBMCs of SG1. (A) Schematic representation of HIV-1 genome. Numbers represent nucleotide positions. (B) Second-round-PCR products encompassing the entire HIV-1 genome of SG1. These PCR fragments were subjected to sequence analysis.

In most cases, gel analysis of nested-PCR products showed single sharp bands at the expected molecular weight in both SG1 and 8e5LAV control cells. In these cases, the amplified products obtained by triplicate PCRs were pooled and directly sequenced. In contrast, gel analysis of the nef region and the middle part of the env region (fragments 19 and 17, respectively, in Fig. 1B) gave a multiband pattern. The sequence analysis of these regions was carried out on selected clones. All PCR products were sequenced in both strands by the dideoxy-chain terminator method using a Quick Start kit (Beckman) and run on a CEQ 2000 sequencer. The alignment of SG1 versus HXB2 nucleotide sequences was analyzed by the CLUSTAL W algorithm. Cloning was performed into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and transformation experiments were carried out using Escherichia coli JM109 cells (Promega, Madison, WI). The DNA plasmid of each clone was extracted by use of a miniprep kit (QIAGEN). At least 10 clones were sequenced.

The direct sequence analysis of gag, pol, vif, vpr, tat, and rev genes did not show significant divergences from the HXB2 consensus reference sequence. The entire sequence of these regions is reported in GenBank. Significant alterations were instead observed in the vpu/env overlapping region (fragments 14 and 15 in Fig. 1B). An insertion of nine bases in frame (between nucleotides 6239 and 6240 of the consensus reference sequence) and a deletion of nine bases (spanning nucleotides 6268 to 6276 of the consensus reference sequence) were found. Both rearrangements correspond to the second alpha helix domain of the VPU protein. Similar structural alterations were also found in viral RNA present in plasma.

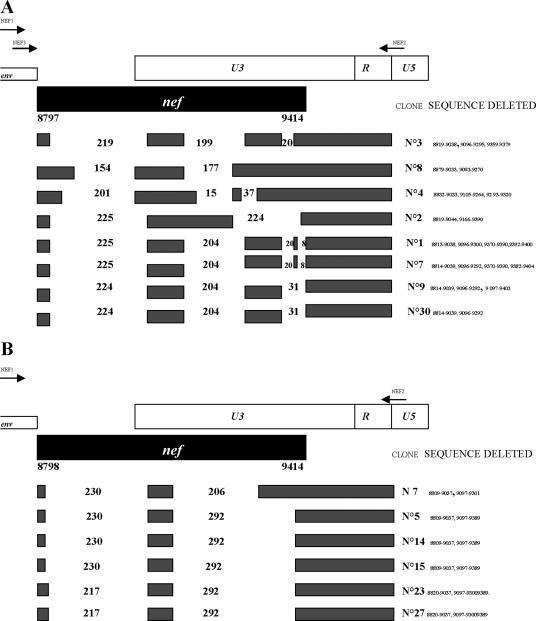

Major genetic alterations were found in the nef-long terminal repeat (LTR) and env regions. The segment containing nef-nef, nef-U3, and R regions obtained by seminested PCR (fragment no. 19 in Fig. 1) (Fig. 2A, top) was cloned and sequenced. All clones contained a single large deletion in the nef-nef region. The nef-U3 region contained a set of deletions of variable sizes (Fig. 2A). A similar but more homogenous pattern of deletions was found by reverse transcription-PCR on viral RNA extracted from a plasma sample of the patient (Fig. 2B). Significantly, the distal part of the LTR-U3 region and the entire R region were intact in all examined clones. These regions contain sequences required for HIV replication, such as NF-κB1 and NF-κB2, Sp1, Sp2, and Sp3, TATA box, and TAR. The direct sequence of LTR-U5 (fragment no. 1 in Fig. 1B) did not show significant changes with respect to the HXB2 control. These data confirm the presence of large deletions in the nef gene, with a further evolution in size with respect to those found in the 1996 samples.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of nef-LTR deletions of HIV-1 detected from patient SG1 in 2005. (A) Deletions in SG1 provirus. The positions of the PCR primers are indicated by arrows: primers NEF1 and NEF2 were used for the first round, and primers NEF2 and NEF3 were used for the second round. Black boxes represent normal sequences; blank spaces represent deletions. Nucleotide numbering refers to HXB2 sequence positions. The numbers in the blank regions represent the sizes (in base pairs) of the deletions. (B) Deletions detected in viral RNA present in plasma by a single-round PCR using primers NEF1/NEF2.

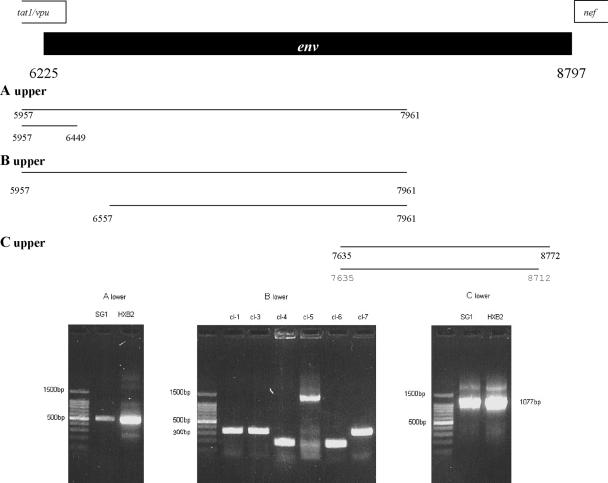

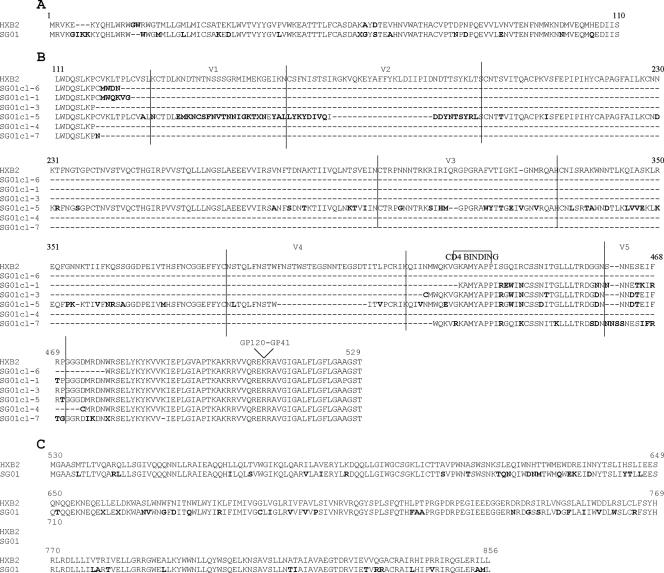

Almost the entire env gene of the provirus harbored in patient SG1 and in 8e5Lav cells was amplified in three fragments (fragments no. 14, 17, and 18 in Fig. 1; fragments A, B, and C in Fig. 3). The proximal part of env (Fig. 3, fragment A) was directly sequenced. The alignment of this segment showed, with respect to HXB2, the insertion of isoleucine, lysine, and lysine between the fifth and the sixth amino acids and the deletion of glycine and tryptophan at positions 14 and 15.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of env gene in the provirus harbored in patient SG1. The upper part of the figure shows a schematic representation of the first and second rounds of the PCR protocols designed for the amplification of the proximal (A upper), middle (B upper), and distal (C upper) parts of the env gene. Nucleotide numbering refers to HXB2 sequence positions. The lower part of the figure shows the gel patterns of the nested-PCR products for the proximal (A lower) and distal (C lower) tracts of env. The lengths of the polymorphisms of the clones derived from the PCR product designed for the middle part of env are shown in panel B lower. cl-1, clone no. 1; cl-3, clone no. 3; etc.

The amplification of the middle part of env (Fig. 3, fragment B) gave a multiband electrophoretic pattern, and the PCR product was cloned. The gel patterns of a representative repertoire of these clones are shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 3. Most of these clones showed a very reduced molecular size (200 to 300 bp, versus 1,270 bp). Other clones, such as clone no. 5, were only a little smaller than expected. The middle Env deduced amino acid sequence is shown in Fig. 4B. Most of the clones (no. 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7) showed a large single deletion containing the V1, V2, V3, and V4 regions. Clone no. 5 showed the loss of a large part of the V2 and V4 regions along with a large change in the V1 domain (Fig. 4B). The CD4 binding domain was deleted in clones no. 4 and 6.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the entire Env protein. Shown are sequences of proximal and distal parts of Env and of the subclones (cl-1, cl-3, cl-4, cl-5, cl-6, and cl-7) derived from a PCR performed for the middle part of Env. The changed amino acids are shown in bold characters. Dashes indicate the deleted amino acids. The start and end of the V1, V2, V3, V4, and V5 domains are indicated by vertical lines. Two oblique lines indicate the gp120-gp41 proteolytic domain.

The direct sequencing of the distal part of env (Fig. 3, fragment C), containing the gp41 cytoplasmic domain, showed several changes and two stop codons (Fig. 4C).

The large alterations of env reported above could alone explain the low rate of viral replication and the failure to isolate virus as evidenced in patient SG1 from 1996 to date. Now the question is whether env and nef destructurations are related. We believe that our patient was first infected with a virus lacking nef but conserving env and that the quasi-species lacking env appeared later. According to this hypothesis, the early infection of SG1 in 1985 was characterized by a clinically severe syndrome, making improbable a contagion with a deeply defective virus.

We believe that, in the absence of nef function, a quasi-species of viruses with truncated Env accumulates. In fact, the nef gene down-regulates class 1 major histocompatibility complex molecules from HIV-1-infected cells (5, 11, 15), leading these cells to evade CD8+ attack. We can speculate that CD8+ cytolysis in patients such as SG1, harboring viruses lacking nef, is highly efficient in eliminating cells presenting wild-type Env molecules, while cells with truncated Env accumulate. We suggest that the more- or less-favorable outcome of patients infected with viruses lacking nef will depend on the high or low efficiency of each individual in eliminating the infected cells by the CD8+ system.

In conclusion, the clinical and virological course of patient SG1 strongly indicates the opportunity to inhibit the function of nef in HIV-1-infected patients. Such an inhibition can be obtained by means of specific drugs and of anti-Nef vaccines.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences reported in this study have been assigned GenBank accession numbers DQ672623 to DQ672627.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research, Research Projects of National Interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Casartelli, N., G. Di Matteo, C. Argentini, C. Cancrini, S. Bernardi, G. Castelli, G. Scarlatti, A. Plebani, P. Rossi, and M. Doria. 2003. Structural defects and variations in the HIV-1 nef gene from rapid, slow and non-progressor children. AIDS 17:1291-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Churchill, M. J., D. I. Rhodes, J. C. Learmont, J. S. Sullivan, S. L. Wesselingh, I. R. C. Cooke, N. J. Deacon, and P. R. Gorry. 2006. Longitudinal analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef/long terminal repeat sequences in a cohort of long-term survivors infected from a single source. J. Virol. 80:1047-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deacon, N. J., A. Tsykin, A. Solomon, K. Smith, M. Ludford-Menting, D. J. Hooker, D. A. McPhee, A. L. Greenway, A. Ellet, C. Chatfield, V. A. Lawson, S. Crow, A. Maerz, S. Sonza, J. Learmont, J. S. Sullivan, A. Cunningham, D. Dwyer, D. Dowton, and J. Mills. 1995. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science 270:987-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desrosiers, R. C., J. D. Lifson, J. S. Gibbs, S. C. Czajak, A. Y. Howe, L. O. Arthur, and R. P. Johnson. 1998. Identification of highly attenuated mutants of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 72:1431-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg, M. E., A. J. Iafrate, and J. Skowronski. 1998. The SH3 domain-binding surface and an acidic motif in HIV-1 Nef regulate trafficking of class 1 MHC complexes. EMBO J. 17:2777-2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kestler, H. W., K. Mori, D. P. Silva, T. Kodama, N. W. King, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1990. Nef genes of SIV. J. Med. Primatol. 19:421-429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kestler, H. W., D. J. Ringler, K. Mori, D. L. Panicali, P. K. Sehgal, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1991. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus load and development of AIDS. Cell 65:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchhoff, F., T. C. Greenough, D. B. Brettler, J. L. Sullivan, and R. Desrosiers. 1995. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo, M., T. Shima, M. Nishizawa, K. Sudo, S. Iawamuro, T. Okabe, Y. Takebe, and M. Imai. 2005. Identification of attenuated variants of HIV-1 circulating recombinants from 01_AE that are associated with slow disease progression due to gross genetic alteration in the nef/long terminal repeat sequences. J. Infect. Dis. 192:56-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Learmont, J. C., A. F. Geczy, J. Milss, M. D. Lesley, J. Ashton, C. H. Raynes-Greenow, R. J. Garcia, W. B. Dyer, L. McIntyre, R. B. Oerlichs, D. I. Rhodes, N. J. Deacon, and J. S. Sullivan. 1999. Immunologic and virologic status after 14 to 18 years of infection with an attenuated strain of HIV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1715-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Gall, S., L. Erdtmann, S. Benichou, C. Berlioz-Torrent, L. Liu, R. Benarous, J. M. Heard, and O. Schwartz. 1998. Nef interacts with the mu subunits of clathrin adaptor complexes and reveals a cryptic sorting signal in MHC 1 molecules. Immunity 8:483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariani, R., F. Kirchoff, T. C. Greenough, J. L. Sullivan, R. C. Desrosiers, and J. Skowronski. 1996. High frequency of defective nef alleles in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 70:7752-7764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saksena, N. K., Y. C. Ge, B. Wang, S. H. Xiang, D. E. Dweyer, C. Randlc, P. Palasanthiran, J. Ziegler, and A. L. Cunningham. 1996. An HIV-1 infected long-term non progressor (LTNP): molecular analysis of HIV-1 strains in the vpr and nef genes. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore 25:848-854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvi, R., A. R. Garbuglia, A. Di Caro, S. Pulciani, F. Montella, and A. Benedetto. 1998. Grossly defective nef gene sequences in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-seropositive long-term nonprogressor. J. Virol. 72:3646-3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz, O., V. Marechal, S. Le Galls, F. Lemonnier, and J. M. Heard. 1996. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat. Med. 2:338-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]