Abstract

Infectious agents have been proposed to influence susceptibility to autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis. We induced a Th1-mediated central nervous system (CNS) autoimmune disease, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice with an ongoing infection with Mycobacterium bovis strain bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) to study this possibility. C57BL/6 mice infected with live BCG for 6 weeks were immunized with myelin oligodendroglial glycoprotein peptide (MOG35-55) to induce EAE. The clinical severity of EAE was reduced in BCG-infected mice in a BCG dose-dependent manner. Inflammatory-cell infiltration and demyelination of the spinal cord were significantly lessened in BCG-infected animals compared with uninfected EAE controls. ELISPOT and gamma interferon intracellular cytokine analysis of the frequency of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in the CNS and in BCG-induced granulomas and adoptive transfer of MOG35-55-specific green fluorescent protein-expressing cells into BCG-infected animals indicated that nervous tissue-specific (MOG35-55) CD4+ T cells accumulate in the BCG-induced granuloma sites. These data suggest a novel mechanism for infection-mediated modulation of autoimmunity. We demonstrate that redirected trafficking of activated CNS antigen-specific CD4+ T cells to local inflammatory sites induced by BCG infection modulates the initiation and progression of a Th1-mediated CNS autoimmune disease.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a central nervous system autoimmune disease with a relapsing and remitting course, affects both sensory and motor nervous function, commonly in young adults. Symptoms include visual disturbance (sometimes progressing to blindness), loss of sense of touch and coordination, pain, spasticity, and incontinence (40). Infectious agents have been demonstrated to contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases (42), including multiple sclerosis (19). However, accumulated evidence has also suggested that infectious diseases could have a protective effect in autoimmunity.

In particular, mycobacterial components have been shown to modulate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice and other autoimmune diseases. Ben-Nun et al. (4, 6) demonstrated clinical improvement of murine EAE as a result of pretreatment with heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis. While they did not elucidate the mechanism of protection, they defined the specific 12-kDa protein fraction of purified protein derivative that mediated it and characterized it as a member of the heat shock protein family. The 12-kDa protein protects in actively induced EAE but not in EAE induced by encephalitogenic T cells (4, 6). They speculated that protection might be the result of shared T-cell epitopes between mycobacterial heat shock protein and myelin basic protein or proteolipid protein. Activation of T cells by mycobacterial heat shock protein would then be responsible for deletion of autoreactive T-cell clones. However, they were unable to detect any such cross-reactivity.

Another example of mycobacterium-induced protection from EAE was described, in which transforming growth factor β produced by γδ T cells was suggested as a potential mechanism. γδ T cells proliferate in response to mycobacterial antigens (9, 25), and when spleen cells from rats immunized with M. tuberculosis were stimulated with monoclonal antibody against the γδ T-cell receptor, these cells produced transforming growth factor β (11).

Heat-killed mycobacteria in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) have been implicated not only as inducers of inflammatory Th1 cell function, but also as initiating agents in the development of suppressor T-cell populations (17). Heat shock proteins or mycobacterial components were also shown to activate regulatory T-cell networks that could downregulate autoreactive T cells (11-13).

Previously, we demonstrated an attenuated clinical course of EAE when C57BL/6 mice were treated with lyophilized M. tuberculosis in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (36). Also, both CFA and Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine were shown to block diabetes in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice (16, 29, 37). BCG vaccine given to newly diagnosed human diabetics led to clinical remissions of various lengths in 11 of 17 cases (29). M. bovis BCG or Mycobacterium avium infections also protect NOD mice from diabetes (20, 23). Martins and Aguas reported that M. avium can upregulate Fas expression and cytotoxicity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in NOD mice (23). They proposed that these T cells can more efficiently delete autoreactive T cells, thus preventing onset of diabetes.

To support the beneficial role of BCG in human autoimmunity, an inverse relationship between incidence of MS and spontaneous positive tuberculin skin tests was reported by Andersen et al. (3). Those authors suggested that early mycobacterial infection may be protective in MS. BCG vaccine has been used in recent clinical trials for MS and resulted in a 51% reduction in lesions as demonstrated by gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (33). In this clinical trial, Ristori et al. (33) confirmed the apparent paradox that a Th1-promoting immune stimulus can have a beneficial effect in purportedly Th1-mediated autoimmune disease. Finally, children that had smallpox or BCG vaccination have demonstrated a lower incidence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, further emphasizing the role of BCG in modulating autoimmunity (8).

In this work we investigated the effects of an active infection with BCG on the development and course of EAE in C57BL/6 mice. We examined the activation status of the CD4+ population and the distribution of myelin oligodendroglial glycoprotein (MOG) reactive CD4+ T cells in an effort to clarify the mechanism of the modulatory effects of BCG. We demonstrate protection from EAE, characterized by lower incidence, lower mortality, delayed onset, and lower mean peak clinical scores. Our data indicate that MOG peptide-specific CD4+ T cells traffic to BCG granulomas and that their sequestration there contributes to reduced accumulation in the central nervous system (CNS) and reduced severity of EAE. We demonstrate that MOG-specific cells in BCG-infected animals retain their capacity to produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in response to MOG stimulation, both in ELISPOT assays and by intracellular cytokine staining. Our data indicate that chronic local inflammatory sites can redirect the migration of activated autoimmune T cells, thereby reducing the number entering the CNS to below the threshold that is needed to incite EAE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and infections.

Female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and housed at the Animal Care Facility at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Animals were infected by intraperitoneal injection at 4 weeks of age with M. bovis strain BCG, a generous gift of Glenn Fennelly (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Brooklyn, N.Y.), at a dose of 3.4 × 107 or 2.8 × 106 CFU per mouse. After 6 weeks of infection, when the infection is chronic, infected mice and age-matched control mice were induced for EAE.

To confirm and standardize infection, at the time of sacrifice, sections of livers of all infected (and uninfected) animals were examined for granulomas and the presence of sequestered acid-fast bacteria by using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Ziehl-Neelsen stains. All animals in infected groups demonstrated the same level of disease, consistent with same levels of infection, based on numbers of granuloma sites and numbers of acid-fast bacilli.

EAE induction and clinical evaluation.

MOG peptide (MOG35-55), synthesized by CyberSyn, Lenni, Pa., was dissolved at 2 mg/ml in sterile PBS. CFA was supplemented with M. tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) to 5 mg/ml. Equal volumes of MOG and supplemented CFA were emulsified by sonication. One hundred microliters of the emulsion was injected subcutaneously in the scapular region of each mouse (100 μg of MOG/mouse). Pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Inc., Campbell, Calif.) (200 ng/mouse) was injected intraperitoneally on the day of EAE induction and again 2 days later.

Adoptive EAE was induced by intravenous injection of 3 × 106 MOG-specific green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressing CD4+ T cells. This T-cell line was derived from UBI-GFP × C57BL/6 transgenic mice, generously provided by Philippa Marrack and Brian Schaefer (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, National Jewish Medical and Research Center), as described previously (43).

Clinical scores in both actively and adoptively induced EAE were monitored daily in a blind manner and recorded as follows: 0, no clinical disease; 1, flaccid tail; 2, gait disturbance or hind limb weakness; 3, hind limb paralysis and no weight bearing on hind limbs; 4, hind limb and forelimb paralysis and reduced ability to move around the cage; and 5, moribund or dead (36). Intermediate scores were assigned for animals with intermediate symptoms. The mean daily clinical score and standard error of the mean were calculated for each group. The significance of differences was calculated by Student's t test.

Histopathology and quantitation of demyelination.

Animals were anaesthetized with Ketamine (100 μg/g) and Xylazine (10 μg/g) and perfused intracardially with approximately 20 ml of cold PBS. Brains, spinal cords, and sections of liver were removed and preserved in 10% formalin. Tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 10-μm sections were cut. Liver sections were stained either with H&E or by the Ziehl-Neelsen method to detect acid-fast mycobacteria. Spinal cords and brains were stained with either H&E or luxol fast blue to detect myelin. Spinal cord sections were photographed at a magnification of ×100 on a BX40 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, N.Y.) with a CMOS Pro 1000 series digital camera (Sound Vision USA, Wayland, Mass.). Adobe Photoshop images were imported and analyzed by using the Scion Image program (a version of NIH image; Scion Corp, Frederick, Md.). Normally myelinated areas and areas of demyelination of each spinal cord section were outlined and measured. The percent demyelination was calculated for each section and collated over five sections per mouse. JMP statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.) was used to plot analysis of variance data and to calculate P values for comparison of demyelination between groups of mice. P values of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Cell isolations.

Spleen cells were isolated by standard methods and resuspended at 107 cells/ml in HL-1 medium for use in ELISPOT assays or in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) staining buffer for FACS. Splenocytes were irradiated at 2,000 rads for use as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in brain cell cultures.

To isolate brain-infiltrating cells, brains were removed from perfused animals, weighed, and minced with sterile scissors in Hanks balanced salt solution. Brain weights were consistently within a tight range, i.e., 0.42 ± 0.03 g/brain. Minced brains were transferred to Medicon inserts and ground in a Medimachine for 20 to 30 s (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). The cell suspension was transferred to a tube and centrifuged for 7 min at 1,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was aspirated off, and cells were resuspended in 2 ml of 50% Percoll (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.Y.) and carefully overlaid with 2 ml of 30% Percoll. The gradient was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The interface was removed, washed twice, and resuspended in FACS staining buffer or HL-1 medium for ELISPOT. Live cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion before FACS staining or ELISPOT assay.

Lymphocytes were isolated from liver granulomas as described previously (18, 24). Granuloma cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion and plated in HL-1 medium at 5 × 105 viable cells/well for ELISPOT assay.

ELISPOT assays.

ImmunoSpot 96-well plates (Cellular Technology, Cleveland, Ohio) were coated overnight at 4°C with (per well) 100 μl of coating antibody diluted in PBS. The antibodies used were specific for murine IFN-γ (4 μg/ml; PharMingen). Excess coating antibody was discarded, and plates were blocked for 60 to 90 min with 150 μl of PBS-1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) per well. The plates were washed, and spleen cells (106/well) or brain cells (103/well) were plated in HL-1 medium supplemented with 1% l-glutamine. Irradiated spleen cells from a naive C57BL/6 mouse (5 × 105/well) were added to the brain cell wells to act as APCs. Antigenic stimuli included MOG35-55 at 2 μg/ml, or concanavalin A at 5 μg/ml as a positive control (data not shown). The final total volume in all wells was 200 μl. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 and washed five times with PBS-0.5% Tween. Biotinylated secondary antibody to IFN-γ (4 μg/ml; PharMingen) was diluted in PBS-0.5% Tween-1% BSA and added at 100 μl/well. Plates were incubated overnight at 4°C and washed five times with PBS-0.5% Tween. Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase, diluted 1:2,000 in PBS-0.5% Tween-1% BSA, was added at 100 μl/well, and plates were incubated 90 min at room temperature. The plates were washed five times with PBS-0.5% Tween. Colored spots were developed by addition of 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (Pierce Pharmaceuticals, Rockford, Ill.). Plates were scanned on an ImmunoSpot Analyzer (Cellular Technology, Cleveland, Ohio) and quantified with image analysis software.

Flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining.

Splenocytes or brain lymphocytes were stained with saturating concentrations of antibodies at 4°C for 30 min. Monoclonal antibodies used for cell surface staining were purchased from PharMingen and included anti-CD4 (GK1.5) labeled with phycoerythrin (PE), CYCR, or CY5; anti-CD44 (Pgp-1) labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC); anti-CD62L (MEL-14) labeled with APC; anti-LFA-1 labeled with FITC; and anti-CD25 (7D4) labeled with FITC. Anti-CD11b (Mac-1) labeled with CY5 or FITC was prepared by standard methods from the MI/70.15 hybridoma (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.). A total of 106 cells were used for staining, and reactions took place in the presence of unlabeled antibody specific for Fcγ (2.4G2) to block Fc-mediated binding.

For intracellular staining of IFN-γ, single-cell suspensions from spleen (107/ml) or brain lymphocyte preparation (105 cells/ml) were cultured overnight in 96-well plates in RPMI-10% fetal calf serum with or without MOG (20 μg/ml), or in phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin, with Golgistop protein transport inhibitor (1 μl/ml) (PharMingen). Cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in 50 μl of staining buffer (a balanced salt solution containing 1% fetal calf serum and 0.02% sodium azide). After cell surface staining (4°C, 30 min) with anti-CD4, anti-CD8b, and/or anti-CD11b antibodies, cells were washed twice in 300 μl of FACS buffer and resuspended in 150 μl of Cytofix/Cytoperm to permeabilize the cells. Cells were incubated for 20 min at room temperature and then washed twice with Permwash buffer and stained for 30 min on an ice shaker with intracellular antibodies, IFN-γ-PE, or isotype control-PE (PharMingen). The cells were again washed with Permwash buffer and resuspended in FACS fixative (2% paraformaldehyde in PBS). Stained cells were analyzed with a dual-laser FACSCalibur 440 (Becton Dickinson), using Cellquest software.

RESULTS

BCG infection delays the onset and reduces the severity of actively induced EAE in C57BL/6 mice in a dose-dependent manner.

To study the effect of live BCG infection on actively induced EAE, we infected C57BL/6 mice intraperitoneally with 3.4 × 107 CFU of M. bovis (BCG). Following 6 weeks of infection, EAE was induced in age-matched control uninfected and infected animals as described in Materials and Methods.

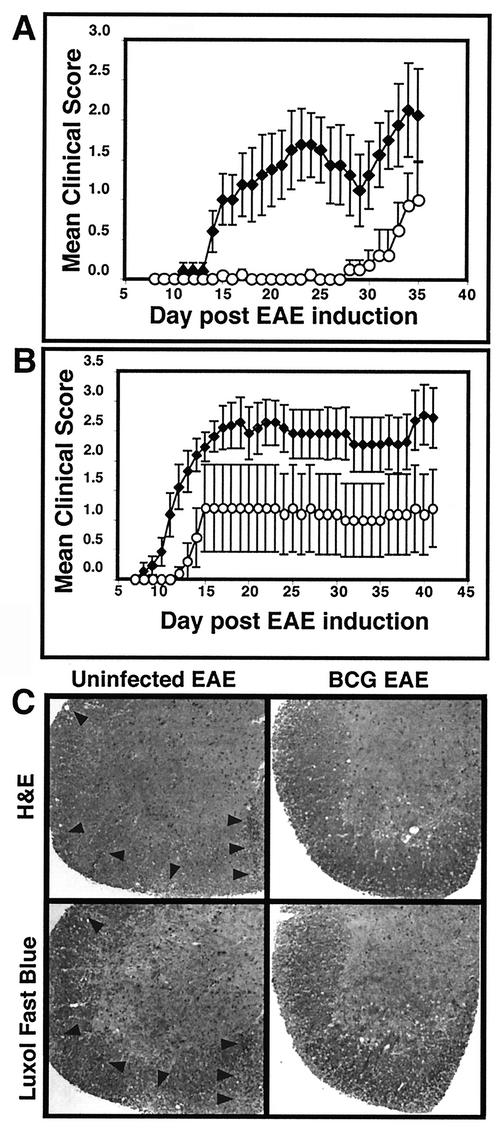

Clinical scores were monitored and recorded daily beginning at day 7 postinduction (Fig. 1A). Infected animals showed either no signs of EAE (defined as a clinical score never exceeding 0.5 [a slight loss of tail tone]) (four of eight animals) or a markedly delayed onset of disease (mean day of onset at day 32.2, compared with day 16.5 for controls) (four of eight animals) (Table 1). Control group animals all developed EAE (10 of 10 animals). The onset of disease in control animals was consistent at 16.5 ± 1.3 days postinduction. Disease in the four infected and symptomatic animals was milder and of later onset, at 32.2 ± 2.2 days (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Infection with M. bovis BCG delays onset and lessens the clinical severity of EAE in a dose-dependent manner. (A and B) Four to 5-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (see Table 1 for numbers of animals) were infected (circles) with 3.4 × 107 CFU (A) or 2.8 × 106 CFU (B) of M. bovis BCG 6 weeks prior to induction of EAE with MOG35-55 peptide in CFA in three separate experiments. Age- and sex-matched C57BL/6 mice were left uninfected (diamonds) prior to EAE induction. The data (mean clinical score ± standard error of the mean) demonstrate delay in and protection from EAE in both low-dose and high-dose infections, with higher-dose infections providing more protection. (C) Spinal cords were extruded from spinal columns by insufflation at day 15 following EAE induction in control uninfected and BCG-infected C57BL/6 mice. Formalin-fixed tissue was sectionedand stained with either H&E or luxol fast blue myelin stain. Uninfected mice demonstrate typical mononuclear cell infiltrates with corresponding areas of demyelination (arrowheads). Spinal cords of BCG-infected animals retain a normal myelin-staining pattern and show no evidence of infiltrates.

TABLE 1.

Effect of BCG infection on EAE in mice

| Dose (CFU/mouse) and infection | Incidence | Mean day of onset ± SDa | Mean peak severity ± SD | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.4 × 107 | ||||

| Control EAE | 10/10 | 16.5 ± 1.3 | 2.72 ± 0.35 | 1/8 |

| BCG-EAE | 4/8 | 32.2 ± 2.2 | 1.19 ± 0.45 | 0/8 |

| 2.8 × 106 | ||||

| Control EAE | 11/11 | 12.0 ± 1.1 | 3.32 ± 0.35 | 3/11 |

| BCG-EAE | 2/5 | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 1.30 ± 0.90 | 0/5 |

Values in boldface are significantly different from control values.

We next examined whether protection from EAE was dependent on the infectious dose of BCG and whether the animals with delayed onset eventually developed equally severe disease. Five 4-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were infected with a more-than-10-fold-lower dose, i.e., 2.8 × 106 CFU of BCG. Following 6 weeks of infection, the infected mice and 11 age-matched controls were induced for EAE as described above. We again observed protection, indicated by lower mean peak clinical scores and delayed onset of disease (Fig. 1B). The lower-dose infection conferred relatively less protection, in that there was a less delayed onset and a lower proportion of disease-free mice. Table 1 shows the disease incidence, peak clinical scores, mean day of onset, and mortality at the two infection levels. None of the BCG-infected mice that had been induced for EAE developed lethal EAE (0 of 13 animals) compared with four deaths among 19 animals in the uninfected groups. These data extend previous studies that have demonstrated protective effects of mycobacterial infections and/or components in autoimmune disease.

Histology demonstrated that spinal cord infiltration and demyelination were prevented or delayed in the BCG-infected animals (Fig. 1C), correlating with clinical scores. EAE is characterized by perivascular infiltrates in the brain and diffuse infiltrates in the spinal cord. In the spinal cord, infiltrated areas demonstrate the demyelination that is responsible for clinical signs of disease. In order to characterize cellular infiltrates and demyelination in BCG-infected mice, we isolated spinal cords from control uninfected and BCG-infected animals at three time points: before induction of EAE; at 15 days after EAE induction, when some of the control group had developed moderately severe disease; and at day 36, when disease had resolved or stabilized in control mice. Spinal cords were fixed; sectioned at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar levels; and stained with H&E to detect cellular infiltrates or with luxol fast blue plus H&E to detect demyelination. Day 0 spinal cords in both control and infected animals appeared normal, with no visible cellular infiltrates and normal myelin patterns (data not shown). At day 15, control animals showed mononuclear cell infiltrates, and the infiltrated areas of spinal cord showed corresponding marked demyelination. At this time point, the spinal cords of BCG-infected mice retained a normal appearance and the animals had no evidence of clinical disease (Fig. 1C). We quantitated the degree of demyelination at day 15 of EAE by using computer image analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Demyelination varied in individual control sections from 0 to 29.5%. In total, approximately 16% of the white matter area in the control, uninfected mice was destroyed. Demyelination was extremely minimal in day 15 sections from infected mice, varying from 0 to 1.1% in individual sections. Overall, BCG-infected mice demonstrated 0.3% demyelination. At day 36, the BCG-infected animals that remained free of EAE symptoms retained normal spinal cord histology, whereas the clinically affected animals showed cellular infiltrates and demyelination similar to those seen in control animals at day 15 (data not shown). These data demonstrate the significant inhibition of cellular infiltration in BCG-infected animals, leading to minimal demyelination in the CNS.

Livers from all mice were examined microscopically at the end of the experiment to confirm active infection. Characteristic granulomas and acid-fast bacteria were present in all infected animals and were not present in uninfected controls (not shown).

BCG infection results in fewer CD4+ T cells in the brains of mice induced for EAE than in uninfected, EAE-induced mice.

Our next experiments were designed to study whether peripheral BCG infection leads to a decreased number or proportion of activated CD4+ T cells in the CNS.

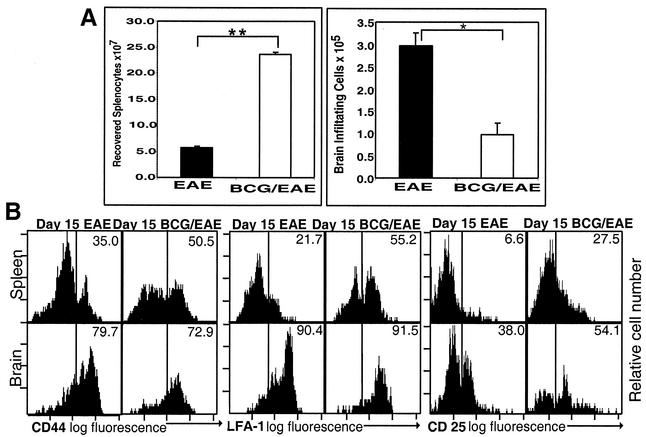

We quantitated cell populations isolated from brain and spleen (Fig. 2A) and characterized activation by examining CD44, LFA-1, and CD25 (interleukin-2Rα) expression on CD4+ cells (Fig. 2B) at day 15 after induction of EAE. We saw a significant (approximately threefold) difference in the absolute numbers of cells isolated from uninfected and BCG-infected mouse brains (uninfected, mean ± SE = 2.97 × 105 ± 0.28 × 105 cells/brain; infected, mean ± SE = 0.97 × 105 ± 0.27 × 105 cells/brain [P < 0.01]). This difference in CNS cell number appears even more significant in light of the fourfold-greater numbers of cells that were isolated from the spleens of the infected mice (uninfected spleen, mean ± SE = 5.70 × 107 ± 1.05 × 107; infected spleen, mean ± SE = 2.37 × 108 ± 0.10 × 108 cells [P < 0.001]). BCG infection resulted in increased numbers of total splenocytes with decreased inflammatory cell infiltrate entering the brain parenchyma following EAE induction. While we saw fewer lymphocytes in the brains of BCG-infected mice, at day 15 after EAE induction, the cells demonstrated a similar postactivation phenotype (CD44high LFA-1high CD25high) in BCG-infected and uninfected mice (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Quantitation and activation status of peripheral and CNS lymphocytes in control EAE and BCG-infected EAE. Splenocytes and brain-infiltrating cells were isolated from BCG-infected C57BL/6 mice or age matched uninfected mice at day 15 after EAE induction. (A) Cells were quantitated by trypan blue exclusion. Results represent mean numbers of cells isolated from spleens and brains of three animals per group, ± standard errors of the means. Statistical significance was calculated by Student's t test. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001. (B) FACS analysis of CD4 gated T lymphocytes isolated from spleens and brains of BCG-infected and uninfected mice induced for EAE at day 15 after EAE induction. Histograms of brain lymphocytes and splenocytes demonstrate a similar postactivated phenotype (CD44high LFA-1high CD25high) in BCG-infected and uninfected groups. Brain weights for these animals were within a very tight range, i.e., 0.42 ± 0.03 g/brain (mean ± standard deviation). All plots are representative of three animals per group.

BCG infection does not inhibit the generation of CNS autoantigen-specific T cells.

The data presented in Fig. 1C and 2A indicated that animals infected with live BCG demonstrated fewer CNS-infiltrating cells than the uninfected EAE controls. One possible explanation was that BCG infection prevented the development of CNS autoantigen-specific T cells. To address this possibility, we monitored IFN-γ production by MOG35-55-specific CD4+ T cells isolated from spleens and brains by intracellular cytokine staining. As shown in Fig. 3, mice normally induced for EAE develop a significant population of MOG-specific CD4+ T cells in the brain. In contrast, their BCG-infected counterparts possess background levels of MOG-specific IFN-γ-producing cells in the brain, despite having an appreciable population of MOG-specific IFN-γ-producing cells systemically in the spleen. Thus, BCG-infected mice induced for EAE are capable of generating MOG-specific T cells, but infiltration of these cells into the brain is diminished, and they do not induce pathology.

FIG. 3.

Intracellular IFN-γ staining of cells isolated at day 15 after EAE induction demonstrates that MOG antigen-specific IFN-γ production is localized differentially in BCG-infected and uninfected mice. Brains and spleens were removed from perfused uninfected and BCG-infected mice at day 15 after EAE induction. Cells were isolated and incubated overnight with MOG35-55, phorbol myristate acetate and ionomycin, or medium (untreated) and Golgistop protein transport inhibitor. The cells were surface stained with CD4-CYCR, Mac-1-Cy5 and CD8b-FITC; permeabilized; and stained with either isotype-PE or IFN-γ-PE. Dot plots represent CD8-negative and Mac-1-negative lymphocyte gated events. Uninfected mice induced for EAE demonstrate MOG-specific IFN-γ-producing T cells in the brain that are absent from the BCG-infected animals. Conversely, more MOG-specific T cells remain in the periphery (spleen) in the infected mice. Numbers represent percentages of CD4+ cells that stained for intracellular IFN-γ. Plots are representative of three mice per group.

Both infected and uninfected mice had significant populations of MOG35-55 antigen-specific T cells capable of producing IFN-γ (arguing against induction of anergy as the mechanism of BCG infection-induced protection), but they were localized differently. In the uninfected animals (with EAE), 13.6% of the CD4+ T cells isolated from brain produced IFN-γ in response to MOG35-55 peptide stimulation, consistent with the clinical disease we observed at that time. At the same time, the number of CD4+ T cells from brains of BCG-infected mice producing IFN-γ in response to MOG35-55 stimulation was below the detection level. The reverse was true of splenocytes, in which a higher fractional IFN-γ response to MOG35-55 was seen from CD4+ T cells isolated from infected (3.1%) than from uninfected (0.3%) mice. This fractional increase (about 10-fold) is concurrent with an approximately fourfold increase in total splenocyte recovery, indicating as many as 40 times as many MOG-specific T cells localizing to spleen in BCG-infected as in uninfected animals.

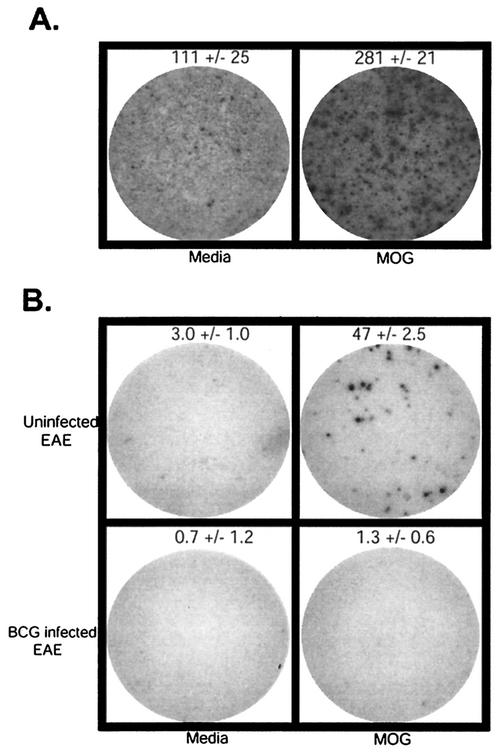

BCG infection traps CNS autoantigen-specific T cells in BCG inflammatory sites.

Given the ability of BCG-infected animals to generate CNS autoantigen-specific T cells which do not enter the brain, we hypothesized that BCG inflammatory sites were sequestering CNS autoantigen-specific T cells, thus blocking their entry into the brain to cause damage. To test this hypothesis, we examined localization of MOG35-55 autoantigen-specific T cells by ELISPOT analysis of lymphocytes isolated from spleen (not shown), from BCG granuloma sites in the liver and from brains of BCG-infected and uninfected mice, 15 days following induction of EAE (Fig. 4). Lymphocytes isolated from BCG granulomas demonstrated constitutive production of IFN-γ, as expected. Interestingly, a large population of MOG antigen-specific cells was found in the granuloma-infiltrating cells (Fig. 4A). Granuloma preparation yielded inadequate cell numbers for ELISPOT analysis in uninfected animals.

FIG. 4.

IFN-γ-producing, MOG antigen-specific T cells localize to granulomas in BCG-infected mice and to brains of control uninfected mice after EAE induction. (A) ELISPOT data from control uninfected and BCG-infected mice at 15 days after EAE induction demonstrate the presence of MOG antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing T cells localized to BCG granulomas. (B) MOG antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing T cells are localized to the brains of uninfected mice, not BCG-infected mice. The wells shown are representative of triplicates. Counts represent the mean ± standard deviation from one of three experiments with similar results. Granuloma cells were plated at 5 × 105/well. Brain cells were plated at 103/well.

Reiterating the intracellular cytokine data, uninfected EAE mice developed 50 MOG-specific IFN-γ-producing T cells per thousand brain lymphocytes. When cells from brains of BCG-infected mice were analyzed, almost no MOG antigen-specific IFN-γ-producing T cells were detected. (Fig. 4B). The absolute number of cells isolated from the brains of uninfected mice with EAE was also significantly higher (approximately threefold) than that isolated from the infected mice at the peak of EAE (uninfected, mean ± SE = 2.97 × 105 ± 0.28 × 105 cells/brain; infected, mean ± SE = 0.97 × 105 ± 0.27 × 105 cells/brain [P < 0.01]).

ELISPOT analysis of MOG35-55-specific splenocytes from BCG-infected and uninfected mice induced for EAE (day 15) was also consistent with the intracellular cytokine data. We detected 554 ± 42 IFN-γ-producing cells/million splenocytes from BCG-infected mice, compared with 117 ± 18 IFN-γ-producing cells/million splenocytes from uninfected mice.

In summary, we demonstrated that MOG35-55-specific cells, capable of producing IFN-γ in response to MOG stimulation, are present in the periphery and traffic to liver granulomas in BCG-infected animals but are underrepresented in the CNS.

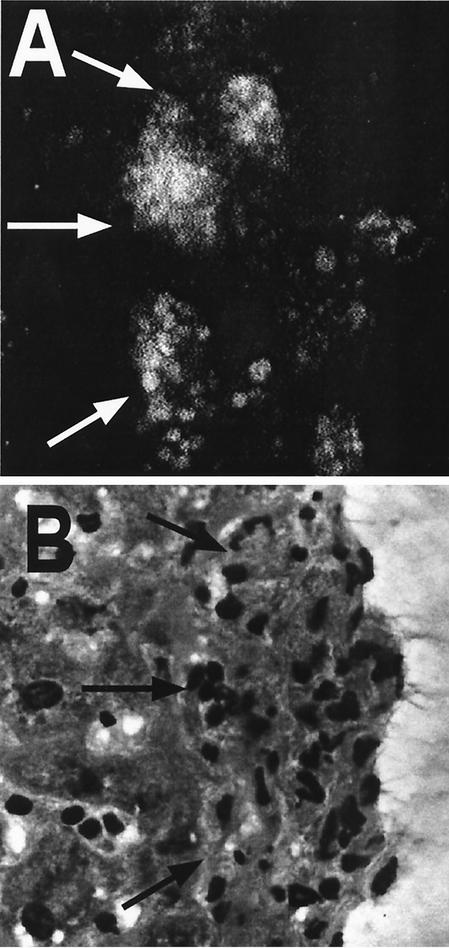

Adoptive transfer of GFP-expressing MOG35-55 antigen-specific T cells results in liver granuloma localization of these cells in BCG-infected animals.

In an effort to confirm that MOG-specific T cells can localize to BCG granuloma sites in live BCG-infected mice, we adoptively transferred MOG35-55-specific T cells expressing GFP into 6-week-BCG-infected and uninfected C57BL/6 mice and monitored the localization of these cells in the CNS and peripheral tissues, in parallel with analyzing the clinical symptoms of EAE. Infected mice were monitored for signs of EAE for 40 days following EAE induction. None of the infected mice developed clinical signs of EAE, whereas uninfected animals had a normal disease progression (data not shown). When we analyzed granuloma sites in the livers and sections from brains and spinal cords for the presence of GFP-expressing cells, significant aggregates of GFP T cells were visible in the granulomatous liver (Fig. 5A). Adjacent sections stained with H&E further confirmed that the GFP-expressing T cells are consistently located in granulomas and not in liver parenchyma (Fig. 5B). Livers at the same time point in EAE-induced but uninfected mice showed no granulomas or aggregates of GFP-expressing T cells (not shown). Occasional GFP-expressing cells were seen in these livers, but they were randomly distributed single cells. These results demonstrate that sites of active BCG infection sequestered activated T cells.

FIG. 5.

When MOG antigen-specific GFP expressing T cells are adoptively transferred into BCG-infected C57BL/6 mice, they localize to liver granulomas. EAE was induced in BCG-infected mice by adoptive transfer of GFP-expressing MOG-specific T cells. Livers were removed and frozen sections were prepared at day 30 after EAE induction. Adjacent sections were examined by confocal microscopy (unstained) (A) or stained with H&E (B). Granulomas that were identified in the H&E sections were found in corresponding locations in the frozen confocal sections, and large numbers of GFP-expressing T cells (white in the confocal images) were localized to the granulomas and absent from surrounding parenchyma.

DISCUSSION

Evidence indicates that Th1-mediated autoimmunity can be downregulated by infectious pathogens such as mycobacteria (13, 16, 22, 34, 38). Several regulatory pathways have been suggested to mediate this downregulation. Bacterial or adjuvant therapy was suggested to be responsible for the generation of Th2-like regulatory cells (17, 34). The involvement of antigenic cross-reactivity (antigenic mimicry) and deletion of potentially autoreactive clones was also suggested (10). Superantigenic stimulation (5, 27, 28, 39) and the involvement of the 65-kDa heat shock proteins (7, 15, 35) have also been implicated in a Th1-induced downregulation of Th1-mediated autoimmunity. In our study, we revisited this question and found that a potentially novel mechanism could also contribute to this effect. We found strong evidence for redirected trafficking of MOG antigen-specific T cells away from the CNS and into BCG-induced granulomas. As a consequence of decreased CNS antigen-specific CD4+-cell number in the CNS, we have demonstrated an ameliorated EAE in BCG-infected mice.

We demonstrated the presence of MOG antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in the granulomas of BCG-infected mice in two different ways. First, MOG peptide stimulation of cells isolated from spleens and granulomas of infected mice induced IFN-γ production as measured by ELISPOT analysis (Fig. 4 and data not shown) and intracellular cytokine staining (Fig. 3), and second, GFP-expressing MOG antigen-specific CD4+ T cells could be directly visualized in liver granulomas by confocal microscopy (Fig. 5). We cannot exclude the possibility that adoptively transferred GFP-positive CD4+ cells were phagocytosed and transferred to the liver by circulating monocytes and macrophages; however, the functional production of IFN-γ by granuloma-localized cells in response to MOG35-55 peptide stimulation argues for the presence of live, functional MOG-specific T cells in the granulomas.

Although we did not analyze the specific chemokines involved in live BCG infection, it is well described that macrophages that phagocytose mycobacteria produce MCP-1, MCP-3, MCP-5, MIP1-α, MIP2, IP-10, and RANTES (26, 32; reviewed in reference 14), which are strong chemoattractants for both macrophages and T cells. Qiu et al. have reported that mycobacterial, type 1-mediated granulomas show predominant expression of chemokines IP-10, MIG, MIP-2, MIP-1α and -β, LIX and lymphotactin (30). Granulomatous inflammation could produce strong signals to attract and retain activated T cells and may potentially decrease the number of activated MOG-specific T cells that can accumulate within the CNS. If a threshold number of these cells is needed to induce disease, competition from a preexisting inflammatory site may keep CNS-infiltrating cell numbers below that threshold. Our data demonstrate that although the proportions of activated (CD44high LFA1high CD25high) cells in the brains of BCG-infected animals were comparable to those in the uninfected animals (Fig. 2), the absolute number of these cells was lower in BCG-infected mice, despite their larger spleens (suggesting more activated T cells in the periphery). CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cells have been demonstrated to downregulate autoimmunity in the CNS in C57BL/6 mice, using MOG35-55 in actively induced EAE. Protection was associated with an increased frequency of MOG35-55-specific Th2 cells and decreased CNS infiltration (21). Although the significance of these cells in our model has to be further investigated, we propose a novel mechanism for amelioration of EAE by BCG infection.

Our data, demonstrating the redirected traffic of MOG-specific cells into liver granulomas induced by BCG, might also suggest the possibility of antigenic cross-reactivity between BCG and MOG. When the mycobacterial gene sequence was compared to the MOG35-55 peptide sequence, we found no obvious homology that would account for, or indicate a role for, antigenic mimicry in our system (1, 2). Primary amino acid sequence homology, however, does not always indicate a peptide's stimulatory capacity. When anchor peptides are known, predictions of stimulatory ligands are somewhat better (31). Ben-Nun and coworkers also excluded cross-reactivity between purified protein derivative or pertussis toxin and myelin basic protein (4), indicating that this mechanism is unlikely to contribute to mycobacterium-induced protection in EAE in their model.

In summary, we describe a potential novel mechanism for protection from the CNS autoimmune disease EAE. Redirected trafficking of autoantigen-specific T cells induced by active infection with BCG likely reduces autoantigen-specific cell numbers and cell frequency in the CNS below a disease-inducing threshold level. We have demonstrated that ongoing infection with BCG consistently decreases the severity of EAE in a dose-dependent fashion and that the improved clinical scores in BCG-infected animals correlate with lack of inflammatory infiltrates and demyelination in the spinal cords of these mice. While we cannot completely rule out any BCG downregulatory effect on MOG antigen-specific T-cell generation in this model, we do show that MOG antigen-specific CD4+ T cells are present in these animals and that they are capable of producing IFN-γ. Infected animals demonstrate that MOG-specific CD4+ T cells are preferentially localized to the spleen and BCG-induced liver granulomas and not to the CNS.

The results presented here suggest that live BCG infection can induce protection in EAE. This might be partially mediated by redirecting of autoimmune Th1 cell trafficking. This mechanism should be added to the already-suggested mechanisms for bacterial regulation of Th1-mediated autoimmunity. There are estimates that up to one-third of the world's population are currently infected with M. tuberculosis (41). This infection is distributed very differently from MS and other autoimmune diseases, with incidences of as high as more than 300 per 100,000 in sub-Saharan Africa and 100 to 300 per 100,000 in most of Asia and extremely low incidences of <10 cases per 100,000 in the United States and Canada and <25 per 100,000 in western Europe (41a). The distribution of tuberculosis is roughly the inverse of the distribution of MS; this inverse distribution may be strictly a coincidence, or the absence of tuberculosis may be an environmental factor in the higher incidence of MS.

Identification of the mechanisms that participate in ameliorated CNS autoimmunity in M. tuberculosis-infected or BCG-immunized individuals will add to our understanding of the role of bacterial infections in CNS autoimmunity and could lead to the development of new strategies for manipulating autoimmune disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippa Marrack and Brian Schaefer (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, National Jewish Medical and Research Center) for providing the UBI-GFP × C57BL/6 transgenic mice and Glenn Fennelly (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Brooklyn, N.Y.), for providing the M. bovis (BCG). Thanks go to Toshi Kinoshita and Khen Macvilay for assistance with histology and flow cytometry.

This work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (grant RG3113A1/1 to Z. Fabry) and the National Institutes of Health (grant RO1-NS 37570-01A2 to Z. Fabry and grant RO1-AI46430 to M. Sandor).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen, E., H. Isager, and K. Hyllested. 1981. Risk factors in multiple sclerosis: tuberculin reactivity, age at measles infection, tonsillectomy and appendectomy. Acta Neurol. Scand. 63:131-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Nun, A., I. Mendel, G. Sappler, and N. Kerlero de Rosbo. 1995. A 12-kDa protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protects mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Protection in the absence of shared T cell epitopes with encephalitogenic proteins. J. Immunol. 154:2939-2948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Nun, A., and S. Yossefi. 1992. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B as a potent suppressant of T lymphocytes: trace levels suppress T lymphocyte proliferative responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:1495-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Nun, A., S. Yossefi, and D. Lehmann. 1993. Protection against autoimmune disease by bacterial agents. II. PPD and pertussis toxin as proteins active in protecting mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 23:689-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnbaum, G., L. Kotilinek, S. D. Miller, C. S. Raine, Y. L. Gao, P. V. Lehmann, and R. S. Gupta. 1998. Heat shock proteins and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. II. Environmental infection and extra-neuraxial inflammation alter the course of chronic relapsing encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 90:149-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Classen, J. B., and D. C. Classen. 1999. Immunization in the first month of life may explain decline in incidence of IDDM in The Netherlands. Autoimmunity 31:43-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constant, P., F. Davodeau, M. A. Peyrat, Y. Poquet, G. Puzo, M. Bonneville, and J. J. Fournie. 1994. Stimulation of human gamma delta T cells by nonpeptidic mycobacterial ligands. Science 264:267-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coutinho, A., and W. Haas. 2001. In vivo models of dominant T-cell tolerance: where do we stand today? Trends Immunol. 22:350-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz-Bardales, B. M., S. M. Novaski, A. E. Goes, G. M. Castro, J. Mengel, and L. M. Santos. 2001. Modulation of the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by gammadelta T lymphocytes activated by mycobacterial antigens. Immunol. Investig. 30:245-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feige, U., A. Schulmeister, J. Mollenhauer, K. Brune, and H. Bang. 1994. A constitutive 65 kDa chondrocyte protein as a target antigen in adjuvant arthritis in Lewis rats. Autoimmunity 17:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feige, U., and W. van Eden. 1996. Infection, autoimmunity and autoimmune disease. Experientia Supplementum 77:359-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn, J. L., and J. Chan. 2001. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:93-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao, Y. L., C. F. Brosnan, and C. S. Raine. 1995. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Qualitative and semiquantitative differences in heat shock protein 60 expression in the central nervous system. J. Immunol. 154:3548-3556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazda, L. S., A. G. Baxter, and K. J. Lafferty. 1996. Regulation of autoimmune diabetes: characteristics of non-islet-antigen specific therapies. Immunol. Cell Biol. 74:401-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabie, N., I. Wohl, S. Youssef, G. Wildbaum, and N. Karin. 1999. Expansion of neonatal tolerance to self in adult life. I. The role of a bacterial adjuvant in tolerance spread. Int. Immunol. 11:899-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogan, L. H., W. Markofski, A. Bock, B. Barger, J. D. Morrissey, and M. Sandor. 2001. Mycobacterium bovis BCG-induced granuloma formation depends on gamma interferon and CD40 ligand but does not require CD28. Infect. Immun. 69:2596-2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter, S. F., and D. A. Hafler. 2000. Ubiquitous pathogens: links between infection and autoimmunity in MS? Neurology 55:164-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, J. Y., S. H. Cho, Y. W. Kim, E. C. Jang, S. Y. Park, E. J. Kim, and S. K. Lee. 1999. Effects of BCG, lymphotoxin and bee venom on insulitis and development of IDDM in non-obese diabetic mice. J. Korean Med. Sci. 14:648-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohm, A. P., P. A. Carpentier, H. A. Anger, and S. D. Miller. 2002. Cutting edge: CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells suppress antigen-specific autoreactive immune responses and central nervous system inflammation during active experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 169:4712-4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehmann, D., and A. Ben-Nun. 1992. Bacterial agents protect against autoimmune disease. I. Mice pre-exposed to Bordetella pertussis or Mycobacterium tuberculosis are highly refractory to induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Autoimmun. 5:675-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martins, T. C., and A. P. Aguas. 1999. Mechanisms of Mycobacterium avium-induced resistance against insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice: role of Fas and Th1 cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 115:248-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metwali, A., D. Elliott, A. M. Blum, J. Li, M. Sandor, R. Lynch, N. Noben-Trauth, and J. V. Weinstock. 1996. The granulomatous response in murine Schistosomiasis mansoni does not switch to Th1 in IL-4-deficient C57BL/6 mice. J. Immunol. 157:4546-4553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller, D., P. Pakpreo, J. Filla, K. Pederson, F. Cigel, and V. Malkovska. 1995. Increased gamma-delta T-lymphocyte response to Mycobacterium bovis BCG in major histocompatibility complex class I-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 63:2361-2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orme, I. M., and A. M. Cooper. 1999. Cytokine/chemokine cascades in immunity to tuberculosis. Immunol. Today 20:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papiernik, M. 2001. Natural CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Their role in the control of superantigen responses. Immunol. Rev. 182:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto, M., M. Torten, and S. C. Birnbaum. 1978. Suppression of the in vivo humoral and cellular immune response by staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB). Transplantation 25:320-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin, H. Y., J. F. Elliott, J. R. Lakey, R. V. Rajotte, and B. Singh. 1998. Endogenous immune response to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67) in NOD mice is modulated by adjuvant immunotherapy. J. Autoimmun. 11:591-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu, B., K. A. Frait, F. Reich, E. Komuniecki, and S. W. Chensue. 2001. Chemokine expression dynamics in mycobacterial (type-1) and schistosomal (type-2) antigen-elicited pulmonary granuloma formation. Am. J. Pathol. 158:1503-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regner, M., and P. H. Lambert. 2001. Autoimmunity through infection or immunization? Nat. Immunol. 2:185-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhoades, E. R., A. M. Cooper, and I. M. Orme. 1995. Chemokine response in mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 63:3871-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ristori, G., M. G. Buzzi, U. Sabatini, E. Giugni, S. Bastianello, F. Viselli, C. Buttinelli, S. Ruggieri, C. Colonnese, C. Pozzilli, and M. Salvetti. 1999. Use of Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 53:1588-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rook, G. A., G. Ristori, M. Salvetti, G. Giovannoni, E. J. Thompson, and J. L. Stanford. 2000. Bacterial vaccines for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune disorders. Immunol. Today. 21:503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selmaj, K., C. F. Brosnan, and C. S. Raine. 1991. Colocalization of lymphocytes bearing gamma delta T-cell receptor and heat shock protein hsp65+ oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:6452-6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sewell, D. L., E. K. Reinke, L. H. Hogan, M. Sandor, and Z. Fabry. 2002. Immunoregulation of CNS autoimmunity by helminth and mycobacterial infections. Immunol. Lett. 82:101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shehadeh, N., F. Calcinaro, B. J. Bradley, I. Bruchlim, P. Vardi, and K. J. Lafferty. 1994. Effect of adjuvant therapy on development of diabetes in mouse and man. Lancet 343:706-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silveira, P. A., and A. G. Baxter. 2001. The NOD mouse as a model of SLE. Autoimmunity 34:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stauffer, Y., S. Marguerat, F. Meylan, C. Ucla, N. Sutkowski, B. Huber, T. Pelet, and B. Conrad. 2001. Interferon-alpha-induced endogenous superantigen. a model linking environment and autoimmunity. Immunity 15:591-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinman, L. 1996. Multiple sclerosis: a coordinated immunological attack against myelin in the central nervous system. Cell 85:299-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Crevel, R., T. H. Ottenhoff, and J. W. van der Meer. 2002. Innate immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:294-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41a.World Health Organization. 2002. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. WHO Report 2002. WHO/CDS/TB/2002.295.

- 42.Wucherpfennig, K. W. 2001. Mechanisms for the induction of autoimmunity by infectious agents. J. Clin. Investig. 108:1097-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao, M. L., and R. B. Fritz. 1998. Acute and relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in IL-4- and alpha/beta T cell-deficient C57BL/6 mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 87:171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]