Abstract

Objective: To identify the major influences in the development of expert male National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I certified athletic trainers.

Design and Setting: The participants were individually interviewed, and the data were transcribed and coded.

Subjects: Seven male NCAA Division I certified athletic trainers, who averaged 29 years of experience in the profession and 20 years at the Division I level.

Results: We found 3 higher-order categories that explained the development of the certified athletic trainers and labeled these meaningful experiences, personal attributes, and mentoring. The growth and development of the athletic trainers were influenced by a variety of meaningful experiences that began during their time as students and continued throughout their careers. These experiences involved dealing with challenging job conditions, educational conditions, and attempts to promote and improve the profession. The personal attributes category encompassed the importance of a caring and service-oriented attitude, building relationships with athletes, and maintaining strong bonds within their own families. Mentoring of these individuals occurred both inside and outside the athletic training profession.

Conclusion: We provide a unique view of the development of athletic trainers that should be of interest to those in the field, regardless of years of experience.

Successful individuals in any field seek environments that are congruent with the characteristics that allow them to express their attitudes and values while best using their skills and abilities.1 Although the discipline of athletic training has many positive attributes associated with it, athletic trainers must deal with a number of stressors that may include dual responsibilities (eg, head athletic trainer and curriculum director), lack of resources, and high athlete-to-athletic trainer ratios.2 The demands can make it difficult for the athletic training professional to stay excited and motivated for an extended period. The question then becomes, “What can be done in the profession of athletic training to ensure that those people who enter the profession are prepared for what awaits them?” Our study is an attempt to address this issue.

Krumboldtz and Worthington3 outlined some factors that can help ease the transition for students who are entering the workplace, including the importance of a knowledgeable and respected counselor or mentor. Under the tutelage of this leader, a student's abilities and skills are refined or expanded (or both) in areas such as organization, interpersonal communication, and reasoning.3 After acquiring these skills, students can work specifically in their field of interest, such as health care, electronics, or engineering.3

Research in athletic training has also supported the importance of mentoring with respect to career transition of young professionals. For example, Curtis et al4 found that the clinical experience became more meaningful and beneficial when a supervising athletic trainer or mentor provided guidance and understanding in a given situation. Moreover, the interaction between the student and supervisor positively affected the career development of the student.4

During the last 2 decades, studies on the career development patterns of certified athletic trainers (ATCs) have been sparse. Quantitative studies in career development issues have focused on topics such as the quality of supervision in athletic training education programs,4 factors that affect the professional lives of athletic trainers,5 and the importance of selected employment characteristics.6 An alternative method of data acquisition involves using qualitative research methods to emphasize the processes and meanings that are not examined in terms of quantity, amount, intensity, or frequency.7 Qualitative researchers seek to capture the richness and complexity of individual experiences. For example, why are so many ATCs burning out so early in their careers, or what attracts individuals to the athletic training profession? The answers to these types of questions can be collected using a number of different qualitative research methods, such as observations, narratives, semiotic analyses, and interviews.7

The purpose of our study was to conduct an in-depth examination of male National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I ATCs who have been identified as leaders in their field based on their longevity and contributions to the field of athletic training. In particular, what factors helped contribute to their rise to prominence? A qualitative method was used to help meet the goals of the study. This allowed the ATCs an opportunity to describe their experiences from a phenomenologic perspective and, thus, maximized the opportunity for them to accurately describe their experiences and for the research team to capture the complexity of this topic.

METHODS

Participants

The criteria for identifying our expert ATCs were in agreement with previous research on expert performers in other domains, in which a minimum of 10 years of experience or more than 10 000 hours of concerted time in the field was required.8,9 These criteria were used as minimum requirements, because the focus was to formulate a sample with more than 25 years of experience as an athletic trainer. A panel of 3 ATCs who were familiar with possible candidates generated a list of 23 potential male subjects from various universities across the United States. Each candidate was then contacted by telephone and given a brief explanation of the study. The final group of 7 participants from 6 different states was determined by their willingness to participate in the study and their availability to meet for an interview before or at the National Athletic Trainers' Association Convention in Kansas City, MO, June 16–19, 1999.

The participants averaged 29 years of experience as professionals in the field of athletic training and 20 years of experience at the Division I level. The participant group also included District and National Athletic Trainers' Association Hall of Fame members. The institutional review board at California State University, Fresno, approved this study, and each participant read, agreed to, and signed a consent form before the interview began.

Interview Technique

We used an open-ended, unstructured interview format. This format allowed the researcher to suggest the topic for discussion and provided the interviewee with the opportunity to answer freely, with few restrictions.7,10 Unlike quantitative methods, which attempt to capture precise data of a codable nature to describe behavior within preestablished categories, qualitative methods are used in an attempt to understand the complex behavior of members of society without imposing strict guidelines that may limit the field of inquiry.7 This type of interview allowed the subjects to stress points they believed were most important in their career development, rather than relying on the investigators' notions.

The interview was enhanced through a technique known as probing. Probes can be used to complete or clarify answers by requesting examples and evidence, by asking the interviewee to finish a thought or answer, or by indicating that the interviewer is following the conversation.10,11 For example, several participants mentioned the names of individuals who influenced their careers. The researcher followed these statements with a probe such as, “Could you tell me more about his/her influence on you?” or “You mentioned your family; would you mind sharing more about that part of your life?”

The participants were asked to share examples of specific situations that they felt enhanced their development as ATCs. No leading questions with hints about desired answers or topics were asked. For example, the term “mentoring” was not suggested to the interviewee at any time. The interviewer always began by saying, “Tell me when you first considered becoming an athletic trainer, what path you took to reach your current position, and what your major influences were.” The interviewee was allowed the latitude to answer in any way he chose. All interviews were tape recorded, and each interaction lasted an average of 50 minutes.

Data Analysis

A full verbatim transcription of each interview was typed at the completion of the interviews. Before any form of analysis began, each transcript was returned to the subject to verify content and accuracy. Minor editing, such as removing names, was performed by the research team to protect the anonymity of the participants. Brackets were used to clarify ambiguous segments of text.

The qualitative analysis was based on the guidelines of Côté et al.12 The process was inductive in that the information emerged from the data rather than being determined before data collection and analysis. First, the text was divided into pieces of information called meaning units.12,13 Tesch13 defined a meaning unit as a comprehensible idea or item that can stand alone. Seven interview transcripts were analyzed, resulting in a total of 281 meaning units. The 3-step process of analysis outlined by Côté et al12 was then followed: (1) creating tags, (2) creating properties, and (3) creating categories.

Each meaning unit was labeled with a tag; each tag described the information contained in each meaning unit. Similar information was given the same tag. A total of 45 tags were created to explain the various developmental patterns, characteristics, and major influences in the lives of the participants.

Similar tags were assembled into higher-order groups called properties. Properties were coded based on the features within the tags and meaning units. For example, loyalty, generosity, independence, and integrity were tags that were regrouped into the higher-order property called personal characteristics. Ten properties were identified for the 45 tags.

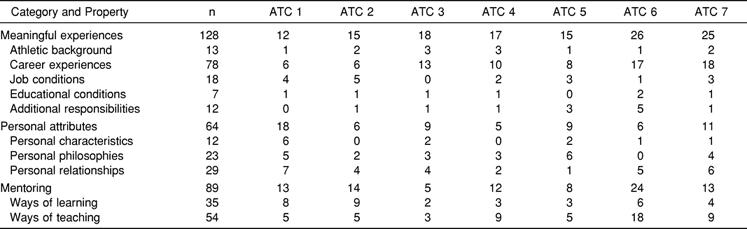

The properties were ultimately assembled into the highest-order group called categories. For example, the properties of personal characteristics, personal philosophies, and personal relationships were placed into a higher-order category called personal attributes. The merging of the 10 properties formed 3 categories. The inductive process was considered complete at the category level when no additional meaningful groupings emerged. A complete list of properties and categories is found in the Table.

Table 1.

Frequency of Meaning Units Within Each Property and Category by Certified Athletic Trainer (ATC)

Trustworthiness of Data Analysis

We used a number of methods to ensure that the conclusions made by the research team were trustworthy.11,14,15 Some examples were peer debriefing, prolonged engagement, and member checking. Peer debriefing refers to a method of analysis verification whereby a second inquirer probes the researcher's biases and explores and clarifies meanings and interpretations.15 In the current study, the debriefer (an ATC knowledgeable in qualitative analysis) checked 25% of the total meaning units for appropriate placement of tags.14 This debriefer was provided with the list of 45 tags and approximately 70 randomly selected meaning units for tagging. The meaning units were provided separately from the tags to eliminate the bias of the researcher. A 91% agreement match was established between the researcher and the second investigator. Discrepancies among researchers were restudied until an agreement was reached regarding the tagging of the meaning units. This assured the research team that the meaning units were placed in the appropriate sections.

Prolonged engagement refers to gaining the knowledge and understanding of the investigated “culture” to detect misinformation introduced by the investigator or the respondents.15 The primary investigator of the current study (R.M.) has been a member of the athletic training “culture” for 5 years. The familiarity of the researcher to the profession helped gain the trust of the participants and avoided the distortion or misinterpretation of information. It also allowed the researcher to understand the context of the information.

Sparkes14 listed member checking as the most crucial technique for establishing credibility. This is a method by which data, interpretations, and conclusions are tested with the participants from whom the data were originally collected.12,15 Feedback from the participants served to ensure the credibility of the analysis. The current study used this technique, and each subject was asked to evaluate a summary of the findings. The summary (2 pages in length) was sent to each of the 7 participants, and 5 were returned. The participants were asked to make any changes, corrections, or revisions to ensure accuracy of the information. All 5 of the participants made positive comments regarding the accuracy and content of the summary. This process provided strong corroboration that the career development paths of expert male ATCs were captured.

RESULTS

The results of the study revealed 3 higher-order categories that significantly influenced the development of expert male NCAA Division I ATCs. They were labeled as meaningful experiences, personal attributes, and mentoring. A description of each category will precede a presentation of supporting citations on the career experiences and major influences of the participants.

Nature of the Data

Although the categories and properties emerged from all 7 athletic trainers, the number of meaning units varied slightly in frequency, ranging from 32 to 56. The difference in the number of meaning units was a result of the open-ended nature of the interviews and does not reflect the knowledge level of the participants in the current study. As well, the higher number of meaning units in the category called meaningful experiences does not mean that it is more important than the other 2 categories. It may, however, relate to the complexity of the category.

Meaningful Experiences

The meaningful experiences category presents a unique look at the personal and professional history of participants by providing them with a foundation of knowledge on which to build their careers. Five properties emerged from this analysis; they were labeled athletic background, career experiences, job conditions, educational conditions, and additional responsibilities.

Athletic Background. All of the participants were involved in sports as youths and in high school. Although they all achieved different levels of success in their chosen sport, all of their athletic careers came to an end due to injury or their inability to be competitive at the next level. As ATC 2 said, “I was involved in athletics in high school. My junior year in high school, I injured my knee. It was a triad injury. In those days, if you tore your anterior cruciate ligament, it was career ending.” In addition, ATC 7 said, “I played high school football and baseball. I didn't consider myself a bad athlete, but when I saw the environment in college, I found out that physically I couldn't match up. It was the first time in my life where I couldn't compete.”

The participants wanted to stay involved in athletics after they were through competing. They all found the ability to do so in some capacity. According to ATC 7, “A freshman football coach told me that there was an opportunity for me to be part of athletics without participating as an athlete. He was the one who got me involved in athletic training. Even though he wasn't an athletic trainer, he taught the athletic training classes at the university.” In addition, ATC 4 said, “I had completed my sophomore year at a junior college as wrestler. An athletic trainer from a local university asked me if I was going to continue to compete. I said, ‘No, but I want to stay involved in athletics.’ He asked me if I would be interested in becoming a student athletic trainer. I began attending the university and working for him as a student athletic trainer.”

Career Experiences. The opportunity to become involved in athletic training came about differently for each of the participants. Some of the ATCs became involved in the profession with other goals in mind, such as coaching. Others became involved through association with other student athletic trainers. According to ATC 3, “I decided that what I wanted to do was go into coaching. Since I had a number of injuries by the time I got into college, I decided to take some athletic training classes. I wanted to become proficient in athletic training and understanding injuries so that when I became a coach, I could help kids avoid suffering like I did.” Also, ATC 6 said, “While working as a student manager, I got to know some of the student trainers that were working with the different teams on campus. I became interested in athletic training and started work as a student athletic trainer. I enjoyed the science aspect of things as well as the athletic side of things.”

Job Conditions. Becoming involved in a developing profession is not always easy. Work conditions were very demanding. One athletic trainer (ATC 3) described his experience as a senior in college:

My senior year in college, the football team had triple-a-day practices. I did the athletic training and the equipment and all the washing for three practices a day. We didn't have a lot of duplicate equipment, so I had to pull things out of lockers just to have enough clothes for practice. It was a busy time. I became proficient enough in the taping aspect that by the time the [staff athletic trainer] would get to practice, I would already have the team taped and prepared for practice. I took pride in that.

Educationally, very few schools had an athletic training curriculum in place. One athletic trainer (ATC 6) stated,

Back at that time, structured education for athletic training was just beginning. I tried to set up my course of study as close to that as possible. I ended up becoming a biology major. I created my own program by combining classes like anatomy, physiology with some physical education courses. I then coupled the classroom education with my experiences as a student athletic trainer.

Accepting a great deal of responsibility in their first job out of college was a common trait among the participants. They were suddenly accountable for the medical care for an entire athletic program. According to ATC 1, “I learned a real respect for what some of the other athletic trainers had accomplished. Here I am, seeing kids with broken collarbones, fingers, all kinds of wild stuff that I didn't have the chance to see at the university, and I had to be responsible for them. It was my job to take care of them. I wanted to do it and I enjoyed doing it.” Another athletic trainer (ATC 7) stated,

It was the first time that I was handling a collegiate program on my own. It also started me in a role of teaching and organizing my own athletic training program. All of a sudden, the entire collegiate athletic program was on my shoulders rather than one sport. I had to learn how to balance football, baseball, basketball, track, and women's sports, while also teaching classes. I never had to do all of those things at the same time before.

Educational Conditions. Educational changes and certification requirements have become more demanding during the last 2 decades. Today's ATCs must be more knowledgeable from an academic standpoint than their predecessors. According to ATC 2,

The level of knowledge that's expected from us is much higher than it was 20 years ago. Twenty years ago you were expected to tape, evaluate an ankle sprain, and give an ultrasound treatment. Now, when you look at the competencies that are required for entry-level athletic trainers, I don't know if I could be an athletic trainer. Educationally, today's students are more qualified to do a lot of things that I'm expected to do at this time.

Additional Responsibilities. The ATCs also took on the responsibilities of understanding the history of the profession and doing their part to improve and promote athletic training. One athletic trainer (ATC 6) said the following:

I developed a real keen sense of the importance of the association and the history of the association. I learned about the evolution of athletic training. Unfortunately, the growth of the profession has made its history less well known. Now, when you go to a convention with 10 000 people, you could walk by Paul Grace or Lindsy McLean and not know who they are or what their importance is to the association.

This profession grew on the hard work of a lot of individuals working full-time jobs and donating their time to make the profession better. The full-time positions on the boards of today used to be held by practicing athletic trainers. In order for the profession to grow, the athletic trainers of today have to be involved and help lead the profession forward. If things aren't going the way they want, then they have a legitimate right to complain. If they sit back and don't get involved then they have no right to say anything.

The athletic trainers looked to make an impact by educating the community. As ATC 4 said,

Realizing that the coaches and administrators had little understanding of what we were doing, I put on an educational workshop for local coaches and administrators. The first year attendance was about 30 people. By the fourth year, we had over 100 people. I brought people in to speak and paid for their expenses through sponsorships. These workshops got a lot of positive publicity in the local area.

The development of athletic trainers is not limited to their career experiences. Personal attributes contribute to their success. The next section identifies characteristics that have enhanced the professional aptitude of the participants.

Personal Attributes

A second higher-order category called personal attributes details the individual nature of ATCs. In particular, this category identifies their personal characteristics, their philosophies, and their relationships both inside and outside the athletic training domain.

Personal Characteristics. Characteristics such as loyalty, generosity, and a strong work ethic helped these individuals succeed in a field where they must put others above themselves. According to ATC 1, “One of the things that I pride myself on is being loyal. If someone works for me and does a good job, I'll do anything I can to help them for the rest of my life. I make that promise to them. If they're loyal, then I return that to them as many times as I can.” In addition, ATC 7 said, “I've had a unique opportunity to give something back to the school. At the same time, the institution has come back and done some things for me. So, it became a 2-way street. I guess my final goal at [the university] would be to make sure that I left this place in a better condition than when I came.”

Personal Philosophies. The work ethic and philosophies of the participants have resulted in the development of a great passion for their work. As ATC 2 said, “For the last 15 years, I haven't worn a watch. The job has never been about how much time I spend at work. I go to work, do my job, and go home when everything is done. If you start looking at the clock and worrying about the fact that you're putting in 14 to 15 hours a day, you won't last very long.” Another athletic trainer (ATC 7) said, “Years ago the philosophy was that the job wasn't done until the job was done and practice wasn't over until everyone went home. Now because of clinical environments and educational controls, the ‘good old boys' have a hard time recognizing there is a 40-hour week. I'm probably one of those.”

The athletic trainers truly cared about the athletes. As ATC 1 said, “To me, and I mean this with all my heart, an athletic trainer is a person who cares more about the athlete than he does himself. The athlete comes first over you. That doesn't mean he's first over your religion or your family; it means he's first over you. Athletes know if you really care. I take my time and pay attention to them.”

The athletic trainers made their availability to the athletes a priority. Their professional philosophies were based on a service-oriented concept. As ATC 1 explains, “I've been an athletic trainer a long time now, almost 30 years, and I haven't missed a day of work, not one. My responsibility is to be there for those athletes, and that's my job. They expect me to be there with them all the time.” According to ATC 2,

I went in and opened the training room at 7 in the morning and closed at 7 or 8 at night. The coaches thought the sun rose and set with me. It wasn't because I knew everything but it was because I was willing to put in the time. I think that that's true with most successful athletic trainers. I think you can make up for what you don't know by working hard and being interested. Spending time with kids and being available to them is very important.”

The personal characteristics of the participants have made their careers more successful and fulfilling. However, the ATCs could not have accomplished everything alone. They received support and direction from the personal relationships they have created inside and outside the sporting environment.

Personal Relationships. The development of a bond between the ATC and the athlete is inevitable while working in an athletic training environment. There is a mutual respect for one another. Relationships that are created can last a lifetime. The following are statements made by ATC 1 and 2, respectively:

As a student, I noticed how much the athletes respected our head athletic trainer, and I noticed how much he cared for them in return. I thought the way they treated him, and the fact that athletes would come back years later to see him, was something special. There was a special bond that he had with the athletes. He taught me to respect the athletes and care for them. The very special bond that we have with athletes as athletic trainers is hard to find anywhere else. I'm not sure everybody has that bond, but I think some of us do.

Being involved with the athletes on a day-to-day basis is what keeps me going. That has made it really easy to stay interested and motivated. It's certainly not money, glamour, or prestige. When a kid comes back on campus and the first place that he comes into is the athletic training room, it says a lot. That's what I will miss the most. Having that relationship with the athletes where they depend upon you and respect you. It's always been a family to me. They become my children.

In a profession where a great deal of time is spent with others, the demanding work environment can limit the time that is spent at home. As ATC 7 states,

Growing up in a small community, my children respected what I did and at the same time resented what I did. I was there at the big events, but the day-to-day battles and struggles in their lives were basically handled by their mother. We always went on the basis that what I brought was quality and not quantity. I would have liked to spend some more time with them so they could understand better where I was coming from. They had the opportunity to get an education. I think they had a good support structure, and they both turned out to be good kids.

Some of the ATCs made special compromises to accommodate both family and work as illustrated by the following statement by ATC 2: “I have 3 boys, and they are very much a part of what I do. They can come in and spend time with dad. They love to do that. Sometimes they come out to the field for practice. So even though I'm working 90 hours a week, they are not spent exclusively away from the family. My family is very much involved in a lot of what I do.”

One athletic trainer (ATC 4) has changed his views on the amount of time spent at work versus time spent at home.

I don't feel that putting in over 70 hours a week is the way to function anymore. There is more to life than work. It was fine when it was just me or my wife and I, but when you start a family you have a commitment to them as well. In order to be able to give of yourself to them, something has to be sacrificed. I have lessened my availability in the athletic training room to be available to my family. When you look at things in proper perspective, the first thing is your faith, then your family, and then your job. If you keep life in that perspective something has to give, so I started altering that in my life. I do my job to the best of my ability. I try to be honest and fair with my athletes and my coaches. I think it is important to keep your life in balance.

Meaningful experiences and personal attributes can be influential in the development of an athletic trainer. Without direction, however, these experiences and qualities can go undeveloped. All of the participants had the benefit of a number of mentoring role models to guide, encourage, and teach them. The next section will describe the final higher-order category, mentoring, in greater detail.

Mentoring

Mentoring involves the educational and developmental relationship between a trusted supervisor and a less experienced individual. Mentors provide their protégés with the opportunity to learn and grow throughout their careers.

Ways of Learning. The participants had the ability to gain knowledge from a number of resources. Most of their knowledge was gained through experience and opportunities working with other ATCs, coaches, or classroom teachers. As ATC 7 explains,

[My head athletic trainer's] influence was really straightforward and very simple. What he gave me was an academic and practical view of athletic training that I never had. He was a real professional. He became a real educational avenue and a professional role model for me. He was a neat man in that he taught me what I wanted to know. I've tried to model myself after him. He didn't spoon feed it. He sat back and let you get into a problem and then tried to help you solve it, if you could. I liked his teaching method because he never browbeat you and he never spoon fed you. I thought that was good.

I learned a lot about intensity from all of our coaches. As we moved up in level, the intensity moved up. Your knowledge of what people can and can't do changes with experience. That was a learning experience from coaches, not the players.

Another athletic trainer (ATC 2) stated, “One instructor I had in high school, who taught music of all things, had a significant passion for what he did. He loved doing what he did and it came through when he dealt with students. He could motivate students to do better than they could do otherwise. That was a significant influence for me.”

Ways of Teaching. The participants promoted learning environments that allowed their students to grow in the profession. The participants taught young athletic trainers by allowing them to make their own mistakes and guiding them back into the right direction, as the following statements by ATCs 3, 6, and 5, respectively, illustrate.

I give people enough freedom to either lengthen their stride or fail. Some athletic trainers like things to be extremely structured. They like to have everything done a certain way all the time. I like to sit down with my students and talk about what direction we are going to take. I'm very strict about the emergency medical stuff and those parameters, but as far as day-to-day operations and assignments, what I do is I step back and I give my graduate assistant the responsibility. I say, “Here are the guidelines and parameters in which we need to stay as far as legality and organization. This is what I have to have done; figure out how to do it.”

Because of the opportunities that I've had, I try to make sure that my students and staff have that same type of opportunity in the program I now run. There are many different ways of doing things, and I let them try their way. They may stumble on to the fact that the way I do it is the better way, but that's for them to learn and not necessarily for me to tell them.

I'm going to make sure that all of our student athletic trainers get tons of experience. I want them to feel like they are getting the experience that they need. I'm not just going to have people move around from sport to sport every 2 weeks. I want them to feel like they are part of the one team. I want them to get to know the players and feel the same things I've felt.

DISCUSSION

Providing an account of the career development experiences and major influences of expert ATCs is a necessary step in documenting the progression of the discipline of athletic training. Before this study, such information had never been the focus of an empirical research study. Our results contribute both theoretically and practically to the athletic training domain. In the former, the results extend research on career development issues to the field of athletic training. In the latter, the results focus on aspects of the profession that are not covered in most university courses but should be of interest to those in the field, regardless of years of experience.

The results of our study are in agreement with the assumptions of the person-environment fit theory reviewed by Swanson and Fouad.1 For example, individuals seek environments that allow them to use their abilities. The theory also assumes that the process is reciprocal in that the person shapes the environment as the environment shapes the person. The ATCs in our study developed their skills and gained experience in athletic training while simultaneously promoting and changing the profession in a positive direction through mentoring and hard work. Working within an “industry-specific” training program3 gave the participants the education and practical skills they needed to function at high levels as ATCs.

Many of the personal attributes of expert athletic trainers were also found in Salmela's16 research on expert coaches. We compared our results with expert coaches rather than with other health care professionals because of the similar time demands and daily contact with athletes. Salmela16 found that expert coaches understood that to reach a high level of success in their profession, they had to work long hours and make personal sacrifices. These coaches demonstrated a genuine concern for their athletes as people. It is possible that some personal elements of coaching and athletic training, such as caring about athletes, exhibiting a passion for one's job, and exuding a strong work ethic, are crucial for achieving success in these domains.

It seems reasonable to conclude that part of the success of the ATCs can be traced to their genuine concern for the well-being of each of their athletes. Although the knowledge of many athletes is limited in relation to anatomy and athletic training, they do know when you care and when you don't. Injuries can occur at any time. When these injuries take place, the athlete becomes vulnerable and seeks an athletic trainer for help, one who cares about him or her a great deal.

Research has shown that mentorships play an important role in the career progression and development of many professionals.17–20 Most research in this area, however, has focused on mentoring in education and business. Only recently has research been performed on mentoring in sport and athletic training. The development of the ATCs in the present study, particularly early in their careers, was greatly enhanced by more experienced individuals. Our results are in agreement with Curtis et al,4 who found that student athletic trainers benefited greatly from the guidance and direction of a mentor. Our results extend their research by providing a qualitative framework so that the participants could explain how their careers were enriched. For example, our ATCs learned from a number of different sources, including classroom teachers, other expert ATCs, and coaches. The phenomenon of being mentored by individuals outside the profession is a rare finding that has not been previously addressed in other mentoring research.

Limitations

Although our study enhances the understanding of the career development experiences of ATCs, some limitations must be addressed. An obvious one is that only male ATCs were sampled in the current study. Female ATCs were not included for 2 main reasons. First is the hypothesized differences that are believed to exist between male and female ATCs. Second, we were unable to acquire a sufficient list of female ATCs with the same level of experience. Future research that examines the career development patterns of female ATCs is recommended.

Certainly, differences face today's ATCs compared with those individuals in our study. For example, the current educational status, increases in sexual equality, and expansion into other nontraditional roles are just some examples. Despite this, we believe that the results of the current study are still very applicable to modern-day athletic training professionals. We strongly believe that a passionate, service-oriented, caring, and hardworking attitude will always be associated with the athletic training profession and is something that needs to be documented. It is possible that possessing these variables is as important or more important than the academic knowledge and resources available to today's ATCs. Along the same line, our intent was not to suggest that the career development paths of the athletic trainers in this study are the best or only ways to become successful in this field. Rather, the intention was to summarize the information from a sample of professionals who have made, and continue to make, a positive contribution to the profession of athletic training.

A final point must be addressed in this section. Unfortunately, it is difficult to translate to the reader the excitement and the passion in the voices of these participants as they shared their thoughts and knowledge with us. More specifically, it was especially rewarding to hear their love for the profession of athletic training.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we attempted to examine an area that has received limited empirical attention in the athletic training literature. Although many individuals have been working in the athletic training profession for years, few have actually documented the steps that took them to the top of their profession. It was our desire to begin an exploration and exchange of information about this area of importance. We believe that our study has contributed to the understanding of the career experiences of expert male Division I ATCs. It also provided a unique appreciation for anyone involved in the profession of athletic training, particularly those experts who perform at the highest level. We hope this article will bring attention to this topic and encourage other practitioners to conduct research in this fascinating area of athletic training. We also strongly support the use of innovative and creative methods to study this area.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rose M. Lyon, Paul Schechter, and those athletic trainers who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- Swanson J L, Fouad N A. Applying theories of person-environment fit to the transition from school to work. Career Dev Q. 1999;47:337–347. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix A E, Acevedo E O, Hebert E. An examination of stress and burnout in certified athletic trainers at Division I-A universities. J Athl Train. 2000;35:139–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumboltz J D, Worthington R L. The school-to-work transition from a learning theory perspective. Career Dev Q. 1999;47:312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis N, Helion J G, Domsohn M. Student athletic trainer perceptions of clinical supervisor behaviors: a critical incident study. J Athl Train. 1998;33:249–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staurowsky E, Scriber K. An analysis of selected factors that affect the work lives of athletic trainers employed in accredited educational programs. J Athl Train. 1998;3:244–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold B L, Gansneder B M, Van Lunen B L, Szczerba J E, Mattacola C G, Perrin D H. Importance of selected athletic trainer employment characteristics in collegiate, sports medicine clinic, and high school settings. J Athl Train. 1998;33:254–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N K, Lincoln Y S, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson K A, Krampe R T, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:363–406. [Google Scholar]

- Simon H, Chase W. Skill in chess. Am Sci. 1973;61:394–403. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H J, Rubin I S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Côté J, Salmela J H, Russell S J. The knowledge of high performance gymnastic coaches: methodological framework. Sport Psychol. 1995;9:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tesch R. Qualitative Research Analysis Types and Software Tools. Falmer Press; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes A C. Validity in qualitative inquiry and the problem of criteria: implications for sport psychology. Sport Psychol. 1998;12:363–386. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y S, Guba E G. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Salmela J H, editor. Great Job Coach: Getting the Edge From Proven Winners. Potentium; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Abell S K, Dillon D R, Hopkins C J, McInerney W D, O'Brien D G. Somebody to count on: mentor/intern relationships in a beginning teacher internship program. Teaching Teacher Educ. 1995;11:173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Borman C, Colson S. Mentoring: an effective career guidance technique. Vocational Guidance Q. 1984;32:192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Carter K. Using cases to frame mentor-novice conversations about teaching. Theory Pract. 1988;27:214–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt D M, Michael C. Mentorship: a career training and development tool. Acad Manage Rev. 1983;8:475–485. [Google Scholar]