Abstract

Objective: To describe the professional socialization process of certified athletic trainers (ATCs) in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I to guide athletic training education and professional development.

Design and Setting: We conducted a qualitative study to explore the experiences related to how participants were socialized into their professional roles in Division I.

Subjects: A total of 16 interviews were conducted with 11 male (68.75%) and 5 female (31.25%) participants who were either currently or formerly affiliated with an NCAA Division I athletic program.

Data Analysis: The interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed inductively using a modified grounded theory approach. Trustworthiness was obtained by peer review, data source triangulation, and member checks.

Results: We identified a discernible pattern of socialization experiences and perceptions among the participants. The professional socialization processes of Division I collegiate ATCs is explained as a 5-phase developmental sequence: (1) envisioning the role, (2) formal preparation, (3) organizational entry, (4) role evolution, and (5) gaining stability.

Conclusions: Examining the professional socialization process provides insights into the experiences of Division I collegiate ATCs as they prepare for their job responsibilities and develop professionally. Appropriate socialization tactics, such as the use of a structured mentoring experience, formal orientation, and staff development programming, can be implemented to promote effective professional development. Additionally, undergraduate students may be well served if they are educated to better use informal learning situations during their initial socializing events.

Keywords: professional development, qualitative research, anticipatory socialization, organizational socialization

Professional socialization serves as a driving influence that has a profound impact on one's professional development. It is also primarily involved with the growth and change of one's thoughts, feelings, attitudes, purpose, and spirit as a professional.1 A better understanding of socialization provides an essential first step to identifying educational strategies to improve the undergraduate education and professional development of certified athletic trainers (ATCs).

Attempting to understand professional socialization as a process has given rise to several phase or stage models in other disciplines.2–4 These models have described the experiences that professionals endure as they learn a particular role. Generally, the professional socialization process is divided into 2 aspects, anticipatory and organizational. Anticipatory socialization includes aspects of socialization before entering a work setting or organization, whereas organizational socialization entails processes that occur after entering the work setting or organization.

The professional socialization process involves learning particular skills, values, attitudes, and norms of behavior and is considered to be a key component of professional preparation and continued development in health and allied medical disciplines.5,6 Although the professional socialization process has been systematically studied from a multitude of perspectives by researchers throughout the 20th century,2,6–17 to date we are unaware of any research reported on the professional socialization of ATCs. Socialization has been known to be both important and inevitable, and in recent years it has been viewed as having the power to effect either negative (ie, burnout) or positive (ie, personal enrichment) results for health care professionals.18

The purpose of our study was to gain insight and understanding about the professional socialization process of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I (NCAA DI) collegiate ATCs. Three research questions guided this aspect of the study: (1) What informal and formal processes socialize ATCs into their professional role at the NCAA DI level? (2) How do ATCs perceive their experiences during their first several years of practice? (3) Do these experiences change over time in a detectable pattern?

METHODS

A qualitative method was used to understand the experiences of ATCs in the NCAA DI context. Qualitative research is an interpretation of data based on the meaning that individuals give to their experiences.19,20 According to Boyle,21 qualitative research is well suited to study individuals who share similar social and cultural characteristics. A qualitative investigation can facilitate the understanding of organizations by examining participant knowledge, meaning, and behavior and requires a researcher to inspect ideas and practices that influence the way people conduct themselves professionally in a specific organizational context.22

Theoretic Framework

Symbolic interactionism provided the theoretic framework for this study. Symbolic interactionism emphasizes the conscious aspects of human behavior related to interaction and suggests that a person is active, rather than passive, in creating his or her conduct but that the expectations of others involved with the interaction are considered.12,15 From a symbolic interactionist perspective, professional socialization is a dynamic, ongoing process marked by one's interaction with others and the environment. Using symbolic interactionism as the theoretic framework allowed us to discover the development of perspectives and meanings related to the participants' socialization processes. We were then able to identify how and why they came to envision themselves as ATCs in the NCAA DI setting, how they perceived their first several years of practice in that context, and how they developed their roles over time.

Participants

A total of 16 interviews were conducted with 11 male (68.75%) and 5 female (31.25%) participants who were either currently or formerly affiliated with NCAA DI programs. Of the 16 participants, 11 were currently full-time collegiate ATCs, 2 were former full-time NCAA DI collegiate ATCs, 1 was a current graduate assistant ATC, and 2 were athletic administrators (1 athletic director and 1 assistant athletic director). The participants collectively represented Districts 3, 4, 5, and 9, and they also represented 4 different NCAA DI athletic conferences. Additionally, the participants (excluding the graduate assistant and administrators) averaged 11.7 years of experience as an ATC, 9.2 years of which were at the NCAA DI level. Eight of these participants were head ATCs, and 5 were assistant ATCs. Northern Illinois University's Institutional Review Board approved the study, and each participant gave informed consent. The participants also gave verbal consent for tape recording before each interview.

Six interviews were arranged with individuals, and several subsequent participants were selected after the original 6 participants suggested the names of other potential participants. This is referred to as a snowball sampling strategy.23 The total number of participants was not determined at the outset of the study; instead, it was based on the concept of redundancy of information or saturation of data. Lincoln and Guba24 identified redundancy of information as being the point at which the researcher determines that no new information is forthcoming or that the same information is being discovered again and again from the participants. On reaching this point, data collection was terminated.

Data Collection

Textual data were collected using semistructured interviews that were conducted by one researcher (W.A.P.). Eleven of the interviews were conducted by telephone, whereas 5 were conducted in person, based on feasibility. Additionally, to triangulate the data and enhance the quality and credibility of the analysis,23,25 athletic administrators and a graduate assistant ATC were interviewed to compare alternative perspectives and further understand the professional socialization processes that occur within this context. Six of the ATCs also consented to and participated in follow-up electronic interviews (e-mail) that permitted clarification as the data were analyzed and to determine that their perspectives had not changed since the original interview.

The interviews were designed to determine the meanings and central themes in the participants' lives and their relationship to them.26 Moreover, the interviews allowed not only the interpretation of the present, but also a re-creation of the past experiences of the participants.27 As such, participants were able to reflect on their past experiences and create a greater understanding of the processes related to their professional development.

To avoid bias in asking questions, a semistructured interview guide was used, and each interview began with the question, “Could you give me a little bit of background about yourself and what brought you to be a certified athletic trainer at the collegiate level?” Examples of other questions or directed statements on the interview guide included the following: (1) “Describe your first few years of being an ATC at the college level,” (2) “What is, or how would you describe, your personal and professional mission?” (3) “Has your mission changed since you first began practicing as an athletic trainer? If so, how?”

Data Analysis

The interview data were transcribed, coded, and analyzed inductively using a modified grounded theory approach.28 Such an inductive analysis is characterized by the detection of concepts, relationships, and understandings,20,29 and the textual data were initially analyzed by creating concepts and categories. The transcripts were read and specific incidents or experiences were given names or labels that represented them. These conceptual statements were then written on index cards, examined, and organized into categories according to their similarities. This was similar to Lincoln and Guba's24 process of identifying “units of data,” such as sentences, paragraphs, or comments, that can provide information about particular concepts. In this study, subcategories were developed based on the anticipatory and organizational socialization experiences and included the following: (1) envisioning the role, (2) formal preparation, (3) organizational entry, (4) role evolution, and (5) gaining stability. Collectively, these subcategories comprised the category “role dynamics: the professional socialization processes of NCAA DI collegiate ATCs.”

Establishing Trustworthiness of the Data Analysis and Interpretation

Trustworthiness of the data analysis and interpretation was established using 3 strategies: (1) data source triangulation, (2) member checks, and (3) peer review. Interviewing alternative participants (athletic administrators and a graduate assistant ATC) and conducting follow-up electronic interviews completed the data source triangulation. This allowed us to determine that the experiences remained consistent at other times or as individuals interacted30 and to ensure the credibility of the study.20,27

Member checks were completed by taking the interpretations of the data to 3 of the participants to see if the researcher's interpretations were reasonable.20 Having an experienced qualitative researcher comment on the findings of the study as they emerged constituted the peer review. The review was accomplished by having this individual examine the recorded transcripts and coding sheets while the various concepts, categories, and themes were explained.

RESULTS

We identified a discernible pattern of career selection influences and organizational-based experiences and perceptions among the participants relative to their challenges and concerns once they entered the collegiate setting. Attempting to understand the experiences of the collegiate ATCs interviewed for this study gave significant insights into the evolution of their professional role and their role stability.

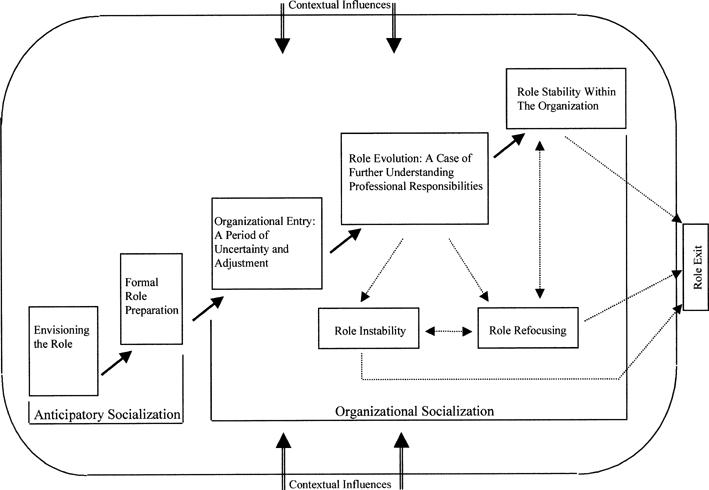

Through the collection and analysis of data, it was determined that the socialization of ATCs occurred in a 5-phase development sequence: (1) envisioning the role, (2) formal preparation, (3) organizational entry, (4) role evolution, and (5) gaining stability (Figure). This model is presented herein and systematically compared with related literature.

Fig. 1.

Processes model of professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I.

Envisioning the Role

Career selection was highly influenced by a personal identity with the culture of sport. Twelve of the current or former full-time collegiate ATCs' primary attraction to athletic training was a fondness for sport, sport-related health care, or high-level competition, or a combination of these. In fact, more than half of the participants were themselves former high school or collegiate athletes, many of whom were injured during sport participation and subsequently cared for by an athletic trainer. These individuals, therefore, were able to identify with a career that was inextricably linked to the sport culture. When asked what brought them to be an athletic trainer at the collegiate level, it was not uncommon for other participants to remark just as one participant explained,

Ever since I could remember, I participated in sports and I enjoyed competition. I enjoyed the camaraderie and being part of a team…so I wanted to find [a career] that I could keep in close contact with that kind of atmosphere and be able to help people.

At this stage of the socialization process, the participants appear to have been strongly influenced by the sport culture and a fondness for competition.

Formal Role Preparation

Once the participants in this study envisioned themselves in an athletic training role, they each took the necessary and logical steps to become an ATC. Although a person's experiences coupled with his or her occupational interests are socializing agents, the more formal anticipatory socialization process begins during an undergraduate professional education. The professional training generally extends from course work to clinical education or field experience or both. The undergraduate experience for the participants in this study, however, did not complete the formal preparation process. That is, a graduate assistantship (GA) seemed necessary to gain an appropriate level of experience to fully prepare them for the NCAA DI collegiate setting.

A GA position appeared to be a rite of passage for becoming an NCAA DI ATC. Except for one individual, each participant in the study had an NCAA DI collegiate athletic GA position. Thus, a GA in the collegiate setting is often a prerequisite to obtaining a collegiate athletic training position, and it is used as training for those aspiring to work in that setting. Unfortunately, however, the participants suggested that the GA is a small developmental step rather than an experience that fully prepares them for the responsibilities of being a full-time NCAA DI ATC.

When asked to compare the GA to the full-time staff position, one collegiate athletic trainer explained:

When I was a graduate assistant, my sport responsibilities were a little different…the types of athletes that you are dealing with and the quantity of the athletes that you are dealing with is different as well as the type and quantity of the coaches that you are dealing with. Now I deal with a larger quantity of coaches on a daily basis and that makes [the job] tougher. I also deal with a larger quantity of student-athletes.

Not only does the quantity of work differ significantly from the GA, but the level of responsibility does also. For example, when asked about the change in role from a graduate assistant to a full-time staff member, one participant explained that a graduate assistant ultimately still had a head ATC or assistant ATC who made final decisions.

Organizational Entry Phase: A Period of Uncertainty and Adjustment

Making a transition from being a graduate assistant to a full-time NCAA DI ATC offered many challenges to the participants. The ATCs who were inducted into the NCAA DI organization consistently stated that they experienced a period of uncertainty, although to varying degrees. Additionally, there was some evidence of role strain in that the bulk of participants in the study suggested that they were often overwhelmed, lacked an understanding of exactly how tasks should be completed in the “new system,” and were astonished by the high volume of work. Thus, the induction period of organizational socialization was a period of uncertainty and adjustment for the ATCs. When asked about her initial collegiate experience, one participant exclaimed it to be “overwhelming, I was put over here at [this facility]…by myself with a graduate assistant in the afternoons …but basically [I was] just sort of thrown into the fires.”

The ATCs entering the NCAA DI settings stated that the job differed slightly from what they expected following their GA positions. The primary differences were the intense volume of required work, the added responsibility, and an occasional uncertainty regarding how to act to “fit in.” One participant, when asked about his initial challenges in collegiate athletics, suggested that administrative acceptance is the primary challenge when entering an organization. He stated, “Why I think the main challenge you have is that of acceptance. Are you going to be accepted by that administration, with the principles and so forth that you stand by?”

The ATCs interviewed in this study overwhelmingly suggested that to adjust to their new professional demands they “learned on the run.” Much of their survival in the organizational entry period was the by-product of a great deal of trial and error as they faced situations for which they felt ill prepared, indicating that their formal education was inadequate. One participant stated:

I went in [to my first collegiate position], and I would try to do something that we had done at [the university where I did my graduate work] and were successful with, but it wasn't successful…[here]. So I'd have to re-evaluate and things like that…I'll admit I learned a lot on the run.

The participants consistently identified a lack of formal induction processes. More specifically, job responsibilities were described in writing, but no formal training, orientation, or learning processes, apart from administrative tasks (eg, vehicle requests, referral procedures, or travel requests), were implemented. When asked about learning their role during the induction process, participants explained that they “learned by doing” and relied informally on colleagues.

Moreover, many participants “reached back in order to move forward” to successfully learn their role. That is, in order for many to meet the demands of their new positions without a formal induction process, they often went to previous mentors for guidance and help.

Despite the formal preparation necessary to enter the collegiate setting, ATCs were not completely prepared for what they experienced. The length of time this stage lasted, however, varied for each participant. Although the participants generally discussed this stage relative to their first year on the job, it was apparent with 2 participants that this stage was extremely brief.

Role Evolution: A Case of Further Understanding the Professional Role

Information was gained about the participants' continued development by asking them to explain their professional mission and whether it had changed since entering the collegiate setting. Two less-experienced collegiate ATCs interviewed (each with only 2 years of full-time staff experience) had trouble explaining their mission. The initial response from the others, however, was that their mission was to provide the best quality of health care possible to the athletes. When asked about how their mission has changed, many remarked on how they had come to understand the full nature of their professional role and realized its comprehensive nature. For example, one participant stated that originally her mission was to provide the best possible health care. However, she eventually learned the other aspects necessary for success:

I think that the student-athletes rely on us in several different areas…academically [and] emotionally…because [athletic trainers] are a nonthreatening group. You know we are not their peers, we are not competing against them for a position on the team, we are not their coaches to whom they have to prove something or be perfect in their eyes. We are not their teachers. We're not the administration. We're not the media. They can sort of let their guard down when we are in their company and…they rely…on you a lot more than for their physical ailments, and I probably didn't realize I was going to be a friend and a mother to them when I first [started my job].

Another ATC stated that his “mission is to be the best athletic trainer possible. It's to keep the student-athlete in the center of the focus and provide the best health care.” When asked about whether his mission and focus had changed since being in collegiate athletics, he stated, “Oh yes, dramatically. At one time, all I was worried about was accolades you know, is the team winning and those sorts of things. You know, if the team wins, do I get a ring?” Over time, though, he moved from focusing on acclamation and prestige to the interpersonal relationships with the athletes.

It appeared that ATCs were deeply influenced by the relationships they had with the athletes they served. Undoubtedly, after spending season after season, road trip after road trip, and practice after practice, adding up to an inordinate number of hours, with their patients (something other health professionals rarely do), the collegiate ATCs came to find that even the sense of mission changes over time. They soon learned that their role included far more than health care for athletic-related injuries and technical aspects of the job. Furthermore, it appeared that they became increasingly connected with and committed to their patients.

Three participants suggested that their mission changed over time to include promoting the profession itself, whereas one head ATC indicated that although his mission is to deliver quality health care, it is also to create an environment that allows his staff to grow both professionally and personally.

Once they better understood their role and evolved as professionals, the participants attempted to gain stability in their role. Role stabilization, however, was a direct, progressive step following role evolution for only a few ATCs. For the others, attempting to gain stability resulted in other steps in the professional socialization process.

Gaining Stability

Conversations with ATCs who have been in their respective settings for several years helped to identify the fifth phase, gaining role stability. In an attempt to stabilize one's professional role, 3 avenues can be taken: (1) stability within, (2) refocusing within, and (3) instability.

Finding “stability within” the organization seemed to occur when the values of the ATC were relatively congruent with the organization's, and fair levels of collegiality and administrative support existed. In these instances, the perception was that the organization was acting in a moral manner. Moreover, ATCs were able to use their skills and have a degree of autonomy in their role. Despite any disagreements with the administration, these individuals could live with the organizational constraints and felt as though they still contributed to the organization's success and fulfilled their professional mission. A direct progression to role stability from the role evolution stage was found in 3 instances among all of the interviews. An ATC finding this avenue of role stability was asked why he felt he was successful:

I think part of it is my dedication to the kids and my dedication to the institution…Also, I think I have a fairly high set of morals…to me we have a very ethical program…and I'm pretty proud that we treat everybody equally here. We at least try, and I think the ethical moral standpoint we come from helps everyone out here too.

“Refocusing within” refers to those individuals who believed they did not have adequate organizational support or commitment as it pertained to their role, yet they chose to remain in the organization. They realized that their true reward came from helping the student-athletes and being a trusted health care provider. These individuals learned to “pick their battles” within the organization so they did not become too discouraged:

I've gotten—not discouraged—but…I realized that athletic training is a priority, but it's not one of the main priorities. Winning, the coaches, winning coaches, bringing in money [and] certain programs are more important, and [the administration] will address those needs, and we are support staff, and our needs aren't really addressed. Everyone's [needs] are addressed before ours, and I sort of got very discouraged, and instead of getting all upset about it, I just sort of accepted it and tried to pick the battles instead of trying to fight for everything.

This same ATC, when asked what keeps her continuing as a professional in the collegiate setting, stated the following:

I try to focus on [the student-athletes]…I mean I work with coaches, and I work with [the] administration, but my primary source of responsibility is towards the student-athletes for their physical and mental well being…And then if I can nurse an injury back or get an athlete back on the field…that makes me feel good…And I always try to focus on them, even if the coaches complain, or the administration wants us to do more.

“Role instability” refers to the ATCs who were unable to find adequate organizational support or commitment necessary for them to fulfill their professional mission. Subsequently, these individuals removed themselves from the organization and took another position. This occurred with 3 ATCs. For example, one athletic trainer explained how he felt so controlled by some aspects of the organization that he would not be able to adequately attain his professional goals:

I would say that the major reason for leaving the collegiate setting is that I reached a point where I was tired of having my life dictated by other people. And, as much as I could be responsible and lead our staff of athletic trainers and student athletic trainers, I was limited in that our ability to function was always related to what was dictated by everyone else [in the organization]. And the second part of it was that no matter how hard I worked, I never felt like it was enough, or that it was good enough. An example would be that if a basketball player hurt their knee and they were going to see an orthopaedic surgeon tomorrow, you know it was never “That's great, I'm glad you could get them in,” it was “Why can't they be seen today? Why are we waiting on this, why aren't they doing…their surgery now, why is the MRI scheduled for Friday and today's Monday?”

It must be made clear that role exiting occurred not only with those ATCs experiencing role instability, but with one individual who refocused within and another who experienced a long period of role stability. For example, one participant explained that after being in a period of role stability for 13 years, he was influenced by organizational changes that eventually led to his exiting his role.

I stayed there for 13 years, and it wasn't until the 13th year that another administrator came in and a coach who [also] administered and started actually using steroids with the team at that time. And then I bailed out. I got out of there. There was no hope for me. They didn't like me, and I didn't like them, and I lost everything. They brought in a new group of team doctors. They …[dismissed]…the doctors that had been there since I had [been there] and hired a new bunch. So I had no support there. I lost that. And once I lost that, I knew there was no hope for me. So I bailed. I got out.

DISCUSSION

Investigating the experiences of NCAA DI collegiate ATCs from a process perspective identifies the transitional periods in their anticipatory and organizational socialization. The following section will compare our results with the socialization literature.

Anticipatory Socialization

Consistent with the literature,31 the experiences throughout the participants' lives and interactions with significant others and the organization influenced their professional role and career choices. The anticipatory socialization stage is forged by several cultural influences, including the professional discipline, professional influences, individual factors, and societal influences.2 Anticipatory socialization occurs when people are able to anticipate what it would be like as a member of a particular group or occupation to which they do not yet belong.6 With respect to selecting athletic training as a career, participants in this study identified with and were influenced by the culture of sport. Lawson32 stated that “sport socialization is the process by which individuals acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for sport participation as well as the meaning derived from such participation.” Socialization through sport can also nurture one's choice of career related to sport.32 Moreover, socialization through sport can affect the psychosocial development and socialization into roles outside sport.33

Lum30 stated that social roles are imagined by virtue of a person's “reflective thought through the manipulation of symbols.” Such anticipation leads an individual to adopt specific group values and beliefs that facilitate his or her acceptance into a group.2 Therefore, because the participants in this study were highly influenced by the sport culture, they were able to envision themselves in a sport setting.

The anticipatory phase extends into the formal role preparation phase during the undergraduate and graduate student experiences that can be viewed as a process of developing a stronger vision about what it means to be an collegiate athletic trainer.

Organizational Socialization

Entry into the NCAA DI setting begins the organizational socialization of the ATC. As professionals enter an organization to work, they often commit themselves to a particular way of life complete with its rewards, associations, demands, and possibilities.11

Organizational socialization has been described as a learning process whereby individuals understand and make sense of their new context, subsequently “learning the ropes” of a specific organizational role.11 This process simply allows a novice to become a mature practitioner. Initial entry is considered an extension of anticipatory socialization, because it includes those processes that occur before an individual enters an organization and shortly thereafter. Our findings are consistent with other findings that suggest that entering a new position is considered to be an extremely demanding experience.34 Despite the effort put into undergraduate education and using the GA as a rite of passage, many inductees into the NCAA DI athletic organization still had formidable challenges and adjustments to make to adapt to their roles. Such a transitional period, therefore, is an excellent opportunity to consider the use of socialization tactics11,35 and educational interventions, such as a structured mentoring experience, formal training or orientation, and staff development programming, which can offer support from a multitude of perspectives.

Many of the participants reported contacting previous mentors for advice about how to handle challenging situations in their new work environment. Such advice from these mentors helped them to gather themselves and move toward confronting the challenges faced in their work environment. This particular point in their development may be well suited for a more structured mentor relationship with individuals who are in the same or a similar context. Adult mentors can help individuals understand how to better navigate their work environments.

The establishment of mentors and role models is essential to effective lifelong education in the professions.36 The professional socialization literature consistently recommends mentoring as a useful strategy for dealing with issues of induction and role continuance. In fact, mentoring systems at the organizational level are often used “to introduce people to the inner network of the organization, which may assist them in their career advancement.”37

At the organizational level, a formally structured learning orientation may attenuate some of the uncertainty experienced by ATCs entering and evolving through the NCAA DI setting as full-time staff members. One participant suggested that he was oriented about such things as travel procedures and insurance issues but not about other aspects of organizational procedures and norms. A more formalized orientation can help reduce role ambiguity that may lead to role strain.38 Athletic training supervisors and administrators must recognize the day-to-day learning needs of personnel and initiate individualized goals, objectives, and learning plans to facilitate a smooth organizational entry and professional development over time.

The experiences of ATCs inducted into the NCAA DI setting are surprisingly similar to those of teachers documented by Lortie.39 Many teachers learned by doing and entered into a “sink or swim” proposition. They were required to begin their role with a full level of responsibility and perform a full complement of teaching tasks. In like fashion, inducted ATCs are expected to begin their roles with the same responsibilities as an ATC who has several years of experience. Consequently, they learned the finer points of their role by solving problems as best they could, often through trial and error.

These learning experiences during the organizational entry period were informal in nature. Thus, undergraduate student athletic trainers may be well served if they are educated about the initial entry into a professional role and how to better use informal learning situations during their initial socializing events. As such, facilitating self-directed learning among undergraduate students can potentially better prepare them for the independent learning required in the workplace. If practitioners are learning through trial and error, then facilitating reflective practice with undergraduate and graduate-level students becomes paramount. Furthermore, because practitioners are ultimately expected to function independently in a work environment, perhaps more attention should be given to progressing student athletic trainers from a more dependent clinical education environment to a more independent field experience environment during the anticipatory socialization period. Other disciplines have used or required internships, preceptorships, residencies, and fellowships to allow students to gain an appropriate level of experience to prepare for a given professional role.

Given the nature of organizational entry, role evolution, and gaining role stability among participants in this study, it appears advisable that potential ATCs in the NCAA DI setting obtain information relative to the type of orientation and direction they will be given once they enter the setting. Examples include whether a formal mentoring or orientation program exists to help them adjust to their new demands, the amount and type of feedback they will be given, and the type of organizational support they can expect.

Parkay et al40 suggested that individuals could benefit from opportunities to interact with others who are at higher phases of professional development. Similarly, ATCs just entering an organization could benefit from interacting with other ATCs who have gained role stability. Such interactions could facilitate the professional socialization process and the aspects of professional development that have aided them as professionals. This particular strategy may also be helpful for undergraduate student socialization as well, because understanding what to expect from an organization can facilitate a more effective anticipatory socialization.

The findings of professional socialization in this study parallel those reported by Wanous4 after he synthesized many stage models of organizational socialization. He suggested that when individuals enter an organization, they discover either a confirmation or disconfirmation of their expectations and identify work-related conflicts. Soon individuals clarify their roles and learn how to work within the organizational structure. An individual then establishes commitments and learns the behaviors that are consistent with the organization, subsequently becoming an insider. The exception to the model derived from this study, however, is those who did not gain role stability. In these instances, the ATCs' attitudes, values, and ideals were not consistent with the organizations'. These particular individuals refocused their commitments or removed themselves from the organization and took a position at a different university or a different practice setting (eg, sports medicine clinic). It is critical, therefore, that potential staff ATCs gain a great deal of information relative to the organization's values, priorities, and expectations to ensure congruity between the individual and the organization to enhance movement toward role stability in that setting. This is particularly important because a work context may either reinforce or contradict the previous socialization procedures that an ATC has experienced.

Limitations

One limitation of our study is that it was not longitudinal. Rather, we relied on the participants' ability to reflect on past experiences and perceptions with respect to their socialization. Becker et al12 used a similar strategy, however, in a landmark study on the socialization of medical students. The professional development of NCAA DI collegiate ATCs is a prime topic for a longitudinal study to clarify the findings presented herein. Such long-term contact with subjects may uncover significant insights not revealed in this study. Another limitation is linked to the generalizability of the study. Although qualitative research that uses small sample sizes may be transferable to similar contexts, it may not be generalizable. Therefore, additional research investigating the professional socialization process in other contexts or settings is necessary to identify potential educational strategies required to facilitate professional growth.

CONCLUSION

We attempted to answer 3 primary questions: (1) What informal and formal processes socialize ATCs into their professional roles at the NCAA DI level? (2) How do ATCs perceive their experiences during their first several years of practice? (3) Do these experiences change over time in a detectable pattern? The conclusions from this study suggest that the professional socialization process of ATCs into their professional roles at the NCAA DI level appears to be primarily informal or unstructured in nature, as indicated by statements such as “learning on the run” and “learning by doing.” Moreover, this informal socialization process often involved participants' contacting previous mentors for guidance and advice. The socialization experiences during the first several years of practice appeared to create a great deal of uncertainty and adjustment among the ATCs, but they soon learned the multifaceted nature of their responsibilities as their roles evolved.

Our findings give insight into a discernible pattern of not only socialization experiences and perceptions among the participants' organizational socialization but also their anticipatory socialization. As such, the professional socialization processes of DI collegiate ATCs is explained as a 5-phase developmental sequence: (1) envisioning the role, (2) formal preparation, (3) organizational entry, (4) role evolution, and (5) gaining stability.

The professional development process model presented herein explicates the socialization process of NCAA DI collegiate ATCs. Further examination of individuals who have gained role stability may uncover vital and critical events that allowed them to succeed within their organization.

The profession of athletic training has devoted significant effort to reforming undergraduate athletic training education, but the professional socialization process in athletic training education programs has been a neglected research area. Therefore, it is advisable for future researchers to investigate the development of a professional orientation among student athletic trainers to understand the specific professional values and attitudes to which students are socialized.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We give special thanks to Dr Gene Roth for his insightful comments during this study.

REFERENCES

- Colucciello M L. Socialization into nursing: a developmental approach. Nursingconnections. 1990;3:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney W G, Rhoads R A. Faculty Socialization as a Cultural Process: A Mirror of Institutional Commitment. The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development; Washington, DC: 1993. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report 93–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H A. The Nurse's Quest for a Professional Identity. Addison-Wesley; Menlo Park, CA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wanous J P. Organizational Entry: Recruitment, Selection, Orientation, and Socialization of Newcomers. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden J. Professional socialization and health education preparation. J Health Educ. 1995;26:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Harvill L M. Anticipatory socialization of medical students. J Med Educ. 1981;56:431–433. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff J A. Integrating new faculty into the existing department culture. Chronicle Phys Educ Higher Educ. 1995;7(4):12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney W G, Bensimon E M. Promotion and Tenure: Community and Socialization in Academe. State University of New York; Albany, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Templin T J, Schempp P G. Socialization into physical education: its heritage and hope. In: Templin J T, Schempp G P, editors. Socialization Into Physical Education: Learning to Teach. Brown & Benchmark; Indianapolis, IN: 1989. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B E, Saks A M, Lee R T. Socialization and newcomer adjustments: the role of organizational context. Hum Relations. 1998;51:897–927. [Google Scholar]

- Van Maanen J, Schein E H. Toward a theory of organizational socialization. In: Staw B M, Cummings L L, editors. Research in Organizational Behavior. VOL. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1979. pp. 209–264. [Google Scholar]

- Becker H S, Geer B, Hughes E C, Strauss A L. Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit D. A sociological analysis of the extent and influence of professional socialization on the development of a nursing identity among nursing students at two universities in Brisbane, Australia. J Adv Nurs. 1995;21:164–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21010164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie E E. Nurse practitioners: issues in professional socialization. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutter L, Field P A, Campbell I E, Day R. Socialization into nursing: nursing students as learners. J Nurs Educ. 1997;36:149–155. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19970401-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabari J S. Professional socialization: implications for occupational therapy education. Am J Occup Ther. 1985;39:96–102. doi: 10.5014/ajot.39.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark P G. Values in health care professional socialization: implications for geriatric education in interdisciplinary teamwork. Gerontologist. 1997;37:441–451. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtilo R. Foreword. In: Davis C M, editor. Patient Practitioner Interaction: An Experimental Manual for Developing the Art of Health Care. 3rd ed. Slack; Thorofare, NJ: 1998. pp. xvii–xviii. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman D M. Ethnography: Step by Step. Sage Publications; London, England: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S B. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J C. Styles of ethnography. In: Morse J M, editor. Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1984. pp. 159–185. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzman H B. Ethnography in organizations. In: Van Maanan J, editor. Qualitative Research Methods Series. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y S, Guba E G. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson D A, Harris E L, Skipper B L, Allen S D. Doing Naturalistic Inquiry: A Guide to Methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B G, Strauss A L. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A L, Corbin J M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lum J L. Reference groups and professional socialization. In: Hardy M E, Conway M E, editors. Role Theory: Perspectives for Health Professionals. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York, NY: 1978. pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Stroot S A, Williamson K M. Issues and themes of socialization into physical education. J Teach Phys Educ. 1993;12:337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson H A. Occupational socialization and the design of teacher education programs. J Teach Phys Educ. 1986;5:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon H L, Frey J H. A Sociology of Sport. Wadsworth; Belmont, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson K M. A qualitative study on the socialization of beginning physical education teacher educators. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1993;64:188–201. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1993.10608796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneer M E. The influence of professional organizations on teacher development. In: Templin T J, Schempp P G, editors. Socialization into Physical Education: Learning to Teach. Brown & Benchmark; Indianapolis, IN: 1989. pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Houle C O. Continuing Learning in the Professions. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J W, Eggland S A. Principles of Human Resource Development. Perseus; Reading, MA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mobily P R. An examination of role strain for university nurse faculty and its relation to socialization experiences and personal characteristics. J Nurs Educ. 1991;30:73–80. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19910201-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lortie D C. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Parkay F W, Currie G D, Rhodes J W. Professional socialization: a longitudinal study of first-time high school principals. Educ Admin Q. 1992;28:43–75. [Google Scholar]