Abstract

Objectives: To educate athletic trainers and others about the need for emergency planning, to provide guidelines in the development of emergency plans, and to advocate documentation of emergency planning.

Background: Most injuries sustained during athletics or other physical activity are relatively minor. However, potentially limb-threatening or life-threatening emergencies in athletics and physical activity are unpredictable and occur without warning. Proper management of these injuries is critical and should be carried out by trained health services personnel to minimize risk to the injured participant. The organization or institution and its personnel can be placed at risk by the lack of an emergency plan, which may be the foundation of a legal claim.

Recommendations: The National Athletic Trainers' Association recommends that each organization or institution that sponsors athletic activities or events develop and implement a written emergency plan. Emergency plans should be developed by organizational or institutional personnel in consultation with the local emergency medical services. Components of the emergency plan include identification of the personnel involved, specification of the equipment needed to respond to the emergency, and establishment of a communication system to summon emergency care. Additional components of the emergency plan are identification of the mode of emergency transport, specification of the venue or activity location, and incorporation of emergency service personnel into the development and implementation process. Emergency plans should be reviewed and rehearsed annually, with written documentation of any modifications. The plan should identify responsibility for documentation of actions taken during the emergency, evaluation of the emergency response, institutional personnel training, and equipment maintenance. Further, training of the involved personnel should include automatic external defibrillation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, first aid, and prevention of disease transmission.

Keywords: policies and procedures, athletics, planning, catastrophic

Although most injuries that occur in athletics are relatively minor, limb-threatening or life-threatening injuries are unpredictable and can occur without warning.1 Because of the relatively low incidence rate of catastrophic injuries, athletic program personnel may develop a false sense of security over time in the absence of such injuries.1–4 However, these injuries can occur during any physical activity and at any level of participation. Of additional concern is the heightened public awareness associated with the nature and management of such injuries. Medicolegal interests can lead to questions about the qualifications of the personnel involved, the preparedness of the organization for handling these situations, and the actions taken by program personnel.5

Proper emergency management of limb- or life-threatening injuries is critical and should be handled by trained medical and allied health personnel.1–4 Preparation for response to emergencies includes education and training, maintenance of emergency equipment and supplies, appropriate use of personnel, and the formation and implementation of an emergency plan. The emergency plan should be thought of as a blueprint for handling emergencies. A sound emergency plan is easily understood and establishes accountability for the management of emergencies. Furthermore, failure to have an emergency plan can be considered negligence.5

POSITION STATEMENT

Based on an extensive survey of the literature and expert review, the following is the position of the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA):

Each institution or organization that sponsors athletic activities must have a written emergency plan. The emergency plan should be comprehensive and practical, yet flexible enough to adapt to any emergency situation.

Emergency plans must be written documents and should be distributed to certified athletic trainers, team and attending physicians, athletic training students, institutional and organizational safety personnel, institutional and organizational administrators, and coaches. The emergency plan should be developed in consultation with local emergency medical services personnel.

An emergency plan for athletics identifies the personnel involved in carrying out the emergency plan and outlines the qualifications of those executing the plan. Sports medicine professionals, officials, and coaches should be trained in automatic external defibrillation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, first aid, and prevention of disease transmission.

The emergency plan should specify the equipment needed to carry out the tasks required in the event of an emergency. In addition, the emergency plan should outline the location of the emergency equipment. Further, the equipment available should be appropriate to the level of training of the personnel involved.

Establishment of a clear mechanism for communication to appropriate emergency care service providers and identification of the mode of transportation for the injured participant are critical elements of an emergency plan.

The emergency plan should be specific to the activity venue. That is, each activity site should have a defined emergency plan that is derived from the overall institutional or organizational policies on emergency planning.

Emergency plans should incorporate the emergency care facilities to which the injured individual will be taken. Emergency receiving facilities should be notified in advance of scheduled events and contests. Personnel from the emergency receiving facilities should be included in the development of the emergency plan for the institution or organization.

The emergency plan specifies the necessary documentation supporting the implementation and evaluation of the emergency plan. This documentation should identify responsibility for documenting actions taken during the emergency, evaluation of the emergency response, and institutional personnel training.

The emergency plan should be reviewed and rehearsed annually, although more frequent review and rehearsal may be necessary. The results of these reviews and rehearsals should be documented and should indicate whether the emergency plan was modified, with further documentation reflecting how the plan was changed.

All personnel involved with the organization and sponsorship of athletic activities share a professional responsibility to provide for the emergency care of an injured person, including the development and implementation of an emergency plan.

All personnel involved with the organization and sponsorship of athletic activities share a legal duty to develop, implement, and evaluate an emergency plan for all sponsored athletic activities.

The emergency plan should be reviewed by the administration and legal counsel of the sponsoring organization or institution.

BACKGROUND FOR THIS POSITION STAND

Need for Emergency Plans

Emergencies, accidents, and natural disasters are rarely predictable; however, when they do occur, rapid, controlled response will likely make the difference between an effective and an ineffective emergency response. Response can be hindered by the chaotic actions and increased emotions of those who make attempts to help persons who are injured or in danger. One method of control for these unpredictable events is an emergency plan that, if well designed and rehearsed, can provide responders with an organized approach to their reaction. The development of the emergency plan takes care and time to ensure that all necessary contingencies have been included. Lessons learned from major emergencies are also important to consider when developing or revising an emergency plan.

Emergency plans are applicable to agencies of the government, such as law enforcement, fire and rescue, and federal emergency management teams. Furthermore, the use of emergency plans is directly applicable to sport and fitness activities due to the inherent possibility of “an untoward event” that requires access to emergency medical services.6 Of course, when developing an emergency plan for athletics, there is one notable difference from those used by local, state, and federal emergency management personnel. With few exceptions, typically only one athlete, fan, or sideline participant is at risk at one time due to bleeding, internal injury, cardiac arrest, shock, or traumatic head or spine injury. However, emergency planning in athletics should account for an untoward event involving a game official, fan, or sideline participant as well as the participating athlete. Although triage in athletic emergency situations may be rare, this does not minimize the risks involved and the need for carefully prepared emergency care plans. The need for emergency plans in athletics can be divided into 2 major categories: professional and legal.

Professional Need. The first category for consideration in determining the need for emergency plans in athletics is organizational and professional responsibility. Certain governing bodies associated with athletic competition have stated that institutions and organizations must provide for access to emergency medical services if an emergency should occur during any aspect of athletic activity, including in-season and off-season activities.6 The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has recommended that all member institutions develop an emergency plan for their athletic programs.7 The National Federation of State High School Associations has recommended the same at the secondary school level.8 The NCAA states, “Each scheduled practice or contest of an institution-sponsored intercollegiate athletics event, as well as out-of-season practices and skills sessions, should include an emergency plan.”6 The 1999–2000 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook further outlines the key components of the emergency plan.6

Although the 1999–2000 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook is a useful guide, a recent survey of NCAA member institutions revealed that at least 10% of the institutions do not maintain any form of an emergency plan.7 In addition, more than one third of the institutions do not maintain emergency plans for the off-season strength and conditioning activities of the sports.

Personnel coverage at NCAA institutions was also found to be an issue. Nearly all schools provided personnel qualified to administer emergency care for high-risk contact sports, but fewer than two thirds of institutions provided adequate personnel to sports such as cross-country and track.9 In a memorandum dated March 25, 1999, and sent to key personnel at all schools, the president of the NCAA reiterated the recommendations in the 1999–2000 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook to maintain emergency plans for all sport activities, including skill instruction, conditioning, and the nontraditional practice seasons.8

A need for emergency preparedness is further recognized by several national organizations concerned with the delivery of health care services to fitness and sport participants, including the NATA Education Council,10 NATA Board of Certification, Inc,11 American College of Sports Medicine, International Health Racquet and Sports Club Association, American College of Cardiology, and Young Men's Christian Association.12 The NATA-approved athletic training educational competencies for athletic trainers include several references to emergency action plans.10 The knowledge of the key components of an emergency plan, the ability to recognize and appraise emergency plans, and the ability to develop emergency plans are all considered required tasks of the athletic trainer.11 These responsibilities justify the need for the athletic trainer to be involved in the development and application of emergency plans as a partial fulfillment of his or her professional obligations.

In addition to the equipment and personnel involved in emergency response, the emergency plan must include consideration for the sport activity and rules of competition, the weather conditions, and the level of competition.13 The variation in these factors makes venue-specific planning necessary because of the numerous contingencies that may occur. For example, many youth sport activities include both new participants of various sizes who may not know the rules of the activity and those who have participated for years. Also, outdoor sport activities include the possibility of lightning strikes, excessive heat and humidity, and excessive cold, among other environmental concerns that may not be factors during indoor activities. Organizations in areas of the country in which snow may accumulate must consider provisions for ensuring that accessibility by emergency vehicles is not hampered. In addition, the availability of safety equipment that is necessary for participation may be an issue for those in underserved areas. The burden of considering all the possible contingencies in light of the various situations must rest on the professionals, who are best trained to recognize the need for emergency plans and who can develop and implement the venue-specific plans.

Legal Need. Also of significance is the legal basis for the development and application of an emergency plan. It is well known that organizational medical personnel, including certified athletic trainers, have a legal duty as reasonable and prudent professionals to ensure high-quality care of the participants. Of further legal precedence is the accepted standard of care by which allied health professionals are measured.14 This standard of care provides necessary accountability for the actions of both the practitioners and the governing body that oversees those practitioners. The emergency plan has been categorized as a written document that defines the standard of care required during an emergency situation.15 Herbert16 emphasized that well-formulated, adequately written, and periodically rehearsed emergency response protocols are absolutely required by sports medicine programs. Herbert16 further stated that the absence of an emergency plan frequently is the basis for claim and suit based on negligence.

One key indicator for the need for an emergency action plan is the concept of foreseeability. The organization administrators and the members of the sports medicine team must question whether a particular emergency situation has a reasonable possibility of occurring during the sport activity in question.14,15,17 For example, if it is reasonably possible that a catastrophic event such as a head injury, spine injury, or other severe trauma may occur during practice, conditioning, or competition in a sport, a previously prepared emergency plan must be in place. The medical and allied health care personnel must constantly be on guard for potential injuries, and although the occurrence of limb-threatening or life-threatening emergencies is not common, the potential exists. Therefore, prepared emergency responders must have planned in advance for the action to be taken in the event of such an emergency.

Several legal claims and suits have indicated or alluded to the need for emergency plans. In Gathers v Loyola Marymount University,18 the state court settlement included a statement that care was delayed for the injured athlete, and the plaintiffs further alleged that the defendants acted negligently and carelessly in not providing appropriate emergency response. These observations strongly support the need to have clear emergency plans in place, rehearsed, and carried out. In several additional cases,19–21 the courts have stated that proper care was delayed, and it can be reasoned that these delays could have been avoided with the application of a well-prepared emergency plan.

Perhaps the most significant case bearing on the need for emergency planning is Kleinknecht v Gettysburg College, which came before the appellate court in 1993.5,17 In a portion of the decision, the court stated that the college owed a duty to the athletes who are recruited to be athletes at the institution. Further, as a part of that duty, the college must provide “prompt and adequate emergency services while engaged in the school-sponsored intercollegiate athletic activity for which the athlete had been recruited.”17 The same court further ruled that reasonable measures must be ensured and in place to provide prompt treatment of emergency situations. One can conclude from these rulings that planning is critical to ensure prompt and proper emergency medical care, further validating the need for an emergency plan.5

Based on the review of the legal and professional literature, there is no doubt regarding the need for organizations at all levels that sponsor athletic activities to maintain an up-to-date, thorough, and regularly rehearsed emergency plan. Furthermore, members of the sports medicine team have both legal and professional obligations to perform this duty to protect the interests of both the participating athletes and the organization or institution. At best, failure to do so will inevitably result in inefficient athlete care, whereas at worst, gross negligence and potential life-threatening ramifications for the injured athlete or organizational personnel are likely.

Components of Emergency Plans

Organizations that sponsor athletic activities have a duty to develop an emergency plan that can be implemented immediately and to provide appropriate standards of health care to all sports participants.5,14,15,17 Athletic injuries may occur at any time and during any activity. The sports medicine team must be prepared through the formulation of an emergency plan, proper coverage of events, maintenance of appropriate emergency equipment and supplies, use of appropriate emergency medical personnel, and continuing education in the area of emergency medicine. Some potential emergencies may be averted through careful preparticipation physical screenings, adequate medical coverage, safe practice and training techniques, and other safety measures.1,22 However, accidents and injuries are inherent with sports participation, and proper preparation on the part of the sports medicine team will enable each emergency situation to be managed appropriately.

The goal of the sports medicine team is the delivery of the highest possible quality health care to the athlete. Management of the emergency situation that occurs during athletic activities may involve certified athletic trainers and students, emergency medical personnel, physicians, and coaches working together. Just as with an athletic team, the sports medicine team must work together as an efficient unit to accomplish its goals.22 In an emergency situation, the team concept becomes even more critical, because time is crucial and seconds may mean the difference among life, death, and permanent disability. The sharing of information, training, and skills among the various emergency medical care providers helps reach the goal.22,23

Implementation. Once the importance of the emergency plan is realized and the plan has been developed, the plan must be implemented. Implementation of the emergency plan requires 3 basic steps.23

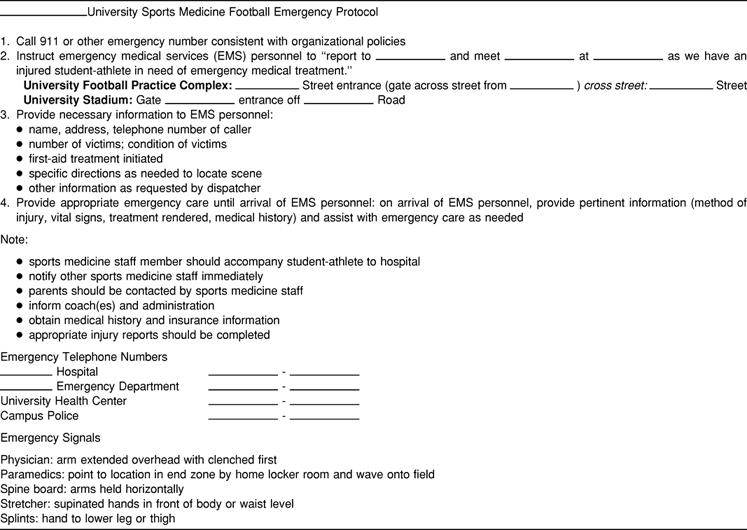

First, the plan must be committed to writing (Table) to provide a clear response mechanism and to allow for continuity among emergency team members.14,16 This can be accomplished by using a flow sheet or an organizational chart. It is also important to have a separate plan or to modify the plan for different athletic venues and for practices and games. Emergency team members, such as the team physician, who are present at games may not necessarily be present at practices. Moreover, the location and type of equipment and communication devices may differ among sports, venues, and activity levels.

Table 1.

Sample Venue-Specific Emergency Protocol

The second step is education.23 It is important to educate all the members of the emergency team regarding the emergency plan. All personnel should be familiar with the emergency medical services system that will provide coverage to their venues and include their input in the emergency plan. Each team member, as well as institution or organization administrators, should have a written copy of the emergency plan that provides documentation of his or her roles and responsibilities in emergency situations. A copy of the emergency plan specific to each venue should be posted prominently by the available telephone.

Third, the emergency plan and procedures have to be rehearsed.16 This provides team members a chance to maintain their emergency skills at a high level of competency. It also provides an opportunity for athletic trainers and emergency medical personnel to communicate regarding specific policies and procedures in their particular region of practice.22 This rehearsal can be accomplished through an annual in-service meeting, preferably before the highest-risk sports season (eg, football, ice hockey, lacrosse). Reviews should be undertaken as needed throughout the sports season, because emergency medical procedures and personnel may change.

Personnel. In an athletic environment, the first person who responds to an emergency situation may vary widely22,24; it may be a coach or a game official, a certified athletic trainer, an emergency medical technician, or a physician. This variation in the first responder makes it imperative that an emergency plan be in place and rehearsed. With a plan in place and rehearsed, these differently trained individuals will be able to work together as an effective team when responding to emergency situations.

The plan should also outline who is responsible for summoning help and clearing the uninjured from the area.

In addition, all personnel associated with practices, competitions, skills instruction, and strength and conditioning activities should have training in automatic external defibrillation and current certification in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, first aid, and the prevention of disease transmission.5,7

Equipment. All necessary supplemental equipment should be at the site and quickly accessible.13,25 Equipment should be in good operating condition, and personnel must be trained in advance to use it properly. Improvements in technology and emergency training require personnel to become familiar with the use of automatic external defibrillators, oxygen, and advanced airways.

It is imperative that health professionals and organizational administrators recognize that recent guidelines published by the American Heart Association call for the availability and use of automatic external defibrillators and that defibrillation is considered a component of basic life support.26 In addition, these guidelines emphasize use of the bag-valve mask in emergency resuscitation and the use of emergency oxygen and advanced airways in emergency care. Personnel should consider receiving appropriate training for these devices and should limit use to devices for which they have been trained.

To ensure that emergency equipment is in working order, all equipment should be checked on a regular basis. Also, the use of equipment should be regularly rehearsed by emergency personnel, and the emergency equipment that is available should be appropriate for the level of training of the emergency medical providers and the venue.

Communication. Access to a working telephone or other telecommunications device, whether fixed or mobile, should be ensured.5,17,21 The communications system should be checked before each practice or competition to ensure proper working order. A back-up communication plan should be in effect in case the primary communication system fails. A listing of appropriate emergency numbers should be either posted by the communication system or readily available, as well as the street address of the venue and specific directions (cross streets, landmarks, and so on) (Table).

Transportation. The emergency plan should encompass transportation of the sick and injured. Emphasis should be placed on having an ambulance on site at high-risk events.15 Emergency medical services response time should also be factored in when determining on-site ambulance coverage. Consideration should be given to the level of transportation service that is available (eg, basic life support, advanced life support) and the equipment and training level of the personnel who staff the ambulance.23

In the event that an ambulance is on site, a location should be designated with rapid access to the site and a cleared route for entering and exiting the venue.19 In the emergency evaluation, the primary survey assists the emergency care provider in identifying emergencies that require critical intervention and in determining transport decisions. In an emergency situation, the athlete should be transported by ambulance to the most appropriate receiving facility, where the necessary staff and equipment can deliver appropriate care.23

In addition, a plan must be available to ensure that the activity areas are supervised if the emergency care provider leaves the site to transport the athlete.

Venue Location. The emergency plan should be venue specific, based on the site of the practice or competition and the activity involved (Table). The plan for each venue should encompass accessibility to emergency personnel, communication system, equipment, and transportation.

At home sites, the host medical providers should orient the visiting medical personnel regarding the site, emergency personnel, equipment available, and procedures associated with the emergency plan.

At away or neutral sites, the coach or athletic trainer should identify, before the event, the availability of communication with emergency medical services and should verify service and reception, particularly in rural areas. In addition, the name and location of the nearest emergency care facility and the availability of an ambulance at the event site should be ascertained.

Emergency Care Facilities. The emergency plan should incorporate access to an emergency medical facility. In selection of the appropriate facility, consideration should be given to the location with respect to the athletic venue. Consideration should also include the level of service available at the emergency facility.

The designated emergency facility and emergency medical services should be notified in advance of athletic events. Furthermore, it is recommended that the emergency plan be reviewed with both medical facility administrators and in-service medical staff regarding pertinent issues involved in athlete care, such as proper removal of athletic equipment in the facility when appropriate.22,23,27

Documentation. A written emergency plan should be reviewed and approved by sports medicine team members and institutions involved. If multiple facilities or sites are to be used, each will require a separate plan. Additional documentation should encompass the following15,16:

Delineation of the person and/or group responsible for documenting the events of the emergency situation

Follow-up documentation on evaluation of response to emergency situation

Documentation of regular rehearsal of the emergency plan

Documentation of personnel training

Documentation of emergency equipment maintenance

It is prudent to invest organizational and institutional ownership in the emergency plan by involving administrators and sport coaches as well as sports medicine personnel in the planning and documentation process. The emergency plan should be reviewed at least annually with all involved personnel. Any revisions or modifications should be reviewed and approved by the personnel involved at all levels of the sponsoring organization or institution and of the responding emergency medical services.

SUMMARY

The purpose of this statement is to present the position of the NATA on emergency planning in athletics. Specifically, professional and legal requirements mandate that organizations or institutions sponsoring athletic activities have a written emergency plan. A well-thought-out emergency plan consists of a number of factors, including, but not necessarily limited to, personnel, equipment, communication, transportation, and documentation. Finally, all sports medicine professionals, coaches, and organizational administrators share professional and legal duties to develop, implement, and evaluate emergency plans for sponsored athletic activities.

Acknowledgments

This position statement was reviewed for the National Athletic Trainers' Association by the Pronouncements Committee and by John Cottone, EdD, ATC; Francis X. Feld, MEd, MS, CRNA, ATC, NREMT-P; and Richard Ray, EdD, ATC.

REFERENCES

- Arnheim D D, Prentice W E. Principles of Athletic Training. 9th ed WCB/McGraw-Hill Inc; Madison, WI: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan M G. Emergency care: planning for the worst. Athl Ther Today. 1998;3(1):12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner D M, Glickman S E. Considerations for the athletic trainer in planning medical coverage for short distance road races. J Athl Train. 1994;29:145–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowlan W P, Davis G A, McDonald B. Preparing for sudden emergencies. Athl Ther Today. 1996;1(1):45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shea J F. Duties of care owed to university athletes in light of Kleinecht. J Coll Univ Law. 1995;21:591–614. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin T, Dick R W. 1999–2000 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook. National Collegiate Athletic Association; Indianapolis, IN: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brown G T. NCAA group raising awareness on medical coverage. NCAA News. 15:6–7. 1999; March. [Google Scholar]

- Shultz S J, Zinder S M, Valovich T C. Sports Medicine Handbook. National Federation of State High School Associations; Indianapolis, IN: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey C W. Memorandum to all National Collegiate Athletic Association Institutions: Emergency Care and Coverage at NCAA Institutions. National Collegiate Athletics Association; Indianapolis, IN: Mar 25, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Athletic Trainers' Association Education Council . Athletic Training Educational Competencies. 3rd ed National Athletic Trainers' Association; Dallas, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Athletic Trainers' Association Board of Certification . Role Delineation Study of the Entry-Level Athletic Trainer Certification Examination. 3rd ed FA Davis; Philadelphia, PA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert D L. Do you need a written emergency response plan? Sports Med Stand Malpract Rep. 1999;11:S17–S24. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin A. Emergency equipment: what to keep on the sidelines. Physician Sportsmed. 1993;21(9):47–54. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1993.11710414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller H. Managing Sports and Risk Management Strategies. Carolina Academic Press; Durham, NC: 1993. pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin J M, Ingersoll C. Athletic Training Management: Concepts and Applications. Mosby-Year Book Inc; St Louis, MO: 1995. pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert D L. Legal Aspects of Sports Medicine. Professional Reports Corp; Canton, OH: 1990. pp. 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinknecht v Gettysburg College, 989 F2d 1360 (3rd Cir 1993)

- Gathers v Loyola Marymount University. Case No. C759027, Los Angeles Super Court (settled 1992)

- Mogabgab v Orleans Parish School Board, 239 So2d 456 (Court of Appeals, Los Angeles, 970)

- Hanson v Kynast, 494 NE2d 1091 (Oh 1986)

- Montgomery v City of Detroit, 448 NW2d 822 (Mich App 1989)

- Kleiner D M. Emergency management of athletic trauma: roles and responsibilities. Emerg Med Serv. 1998;10:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courson R W, Duncan K. The Emergency Plan in Athletic Training Emergency Care. Jones & Bartlett Publishers; Boston, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Athletic Trainers' Association Establishing communication with EMTs. NATA News. Jun, 1994. pp. 4–9.

- Waeckerle J F. Planning for emergencies. Physician Sportsmed. 1991;19(2):35–38. [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association Guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care: international consensus on science. Curr Emerg Cardiovasc Care. 2000;11:3–15. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.114312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner D M, Almquist J L, Bailes J, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association; Dallas, TX: 2001. Prehospital Care of the Spine-Injured Athlete: A Document from the Inter-Association Task Force for Appropriate Care of the Spine-Injured Athlete. [Google Scholar]