Abstract

Objective: To construct interval throwing programs followed by a simulated game for collegiate softball players at all positions. The programs are intended to be used as functional progressions within a comprehensive rehabilitation program for an injured athlete or to augment off-season conditioning workouts.

Design and Setting: We collected data over a single season of National Collegiate Athletic Association softball at the University of Delaware and Goldey Beacom College. We observed 220 half-innings of play and 2785 pitches during data collection.

Subjects: The subjects were collegiate-level softball players at all positions of play.

Measurements: We recorded the number of pitches for pitchers. For catchers, we recorded the number of sprints to back up a play, time in the squat stance, throws back to the pitcher, and the perceived effort and distance of all other throws. We also collected the perceived effort and distance of all throws for infielders and outfielders.

Results: Pitchers threw an average of 89.61 pitches per game; catchers were in the squat stance 14.13 minutes per game; infielders threw the ball between 4.28 times per game and 6.30 times per game; and outfielders threw distances of up to 175 feet.

Conclusions: We devised the interval throwing programs from the data collected, field dimensions, the types of injuries found to occur in softball, and a general understanding of tissue healing. We designed programs that allow a safe and efficient progressive return to sport.

Keywords: simulated game, college softball conditioning, rehabilitation for softball, softball injuries

College softball and women's collegiate sport participation have seen incredible growth over the last 2 decades. The number of female National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) athletes has more than doubled over this time period. During the 1998–1999 academic year, 14 943 of the 145 832 NCAA female athletes were softball players.1,2 Serious injuries in collegiate softball rarely happen, but less serious injuries, which may cause time loss from sport, occur frequently. From NCAA Injury Surveillance System (ISS) data over the last 13 years of softball, the average practice injury rate was 3.3 per 1000 athlete-exposures, and the average game injury rate was 5.0 per 1000 athlete-exposures.3 An athlete-exposure is defined as one athlete participating in one practice or game in which she is exposed to the possibility of athletic injury. Of the injuries sustained, the most common type of injury was sprains (25%), followed by contusions (24%) and strains (13%). In addition, during the 1999 season, 28% of injuries resulted in 7 or more days of time loss.3 Powell and Barber-Foss4 studied sex-related injury patterns in high school sports. They found that 22.9% of softball injuries were classified as forearm, wrist, or hand injuries, while 16.3% of softball injuries were to the upper arm or shoulder. They also noted that throwing accounted for 28.1% of practice injuries and 12.2% of game injuries.4

Very little research has been conducted differentiating fast-pitch softball players from baseball players. The available literature groups the athletes together as throwing athletes and does not account for differences in the games. In contrast to NCAA baseball, NCAA softball contests are played on a smaller field, with a larger ball, in fewer innings of play.5,6 Softball players are injured more frequently than baseball players. Powell and Barber-Foss4 noted differences in injuries over the course of a season between baseball and softball players at the high school level. Softball players had a 27% higher injury rate than baseball players.4

While the differences between baseball and softball encompass players of all positions, the largest difference is in pitching style. Fast-pitch softball players use a windmill style, which is accomplished with the humerus remaining in the plane of the body. Baseball pitchers throw overhead from an abducted position.7,8 The power in the windmill pitch comes from adduction of the arm across the body. Baseball pitchers generate power during internal rotation of the humerus. While the power is attained through different motions, the same muscle, the pectoralis major, is responsible for most of the power in both pitches.7–9 The eccentric follow-through phase of the baseball pitch demonstrates high activity of the external rotators to slow the arm down.10 In contrast, the role of the posterior rotator cuff (external rotators) in the windmill pitch is lessened as the forearm strikes the lateral thigh at ball release, dissipating the energy.7,8,11 Most high-level baseball pitchers throw a high percentage of fastballs. This is not the case in softball. Pitching at the collegiate level of softball usually involves the mastery of 5 different pitches (fastball, rise, curve, drop, change-up). The fastball is not as effective as the other pitches and, therefore, is not thrown as often as it is in baseball.12

A common assumption prevalent in softball is that the pitching style used by softball pitchers does not place significant stress on the athlete. The result is pitchers throwing too many pitches without the benefit of rest. They may pitch in consecutive games and batting practice.13,14 Loosli et al15 observed injury patterns in collegiate softball pitchers from 8 college teams ranked in the top 15 teams in the country in 1989. Nearly half (11 of 24, or 45%) of the players contracted a time-loss injury (modified or missed activity) at some point during the season. Of the 11 time-loss injuries, 9 involved the upper extremity. Also, the pitchers with grade I and II injuries (had pain or complaints but continued to play) averaged more innings per season than those who were uninjured.15

The conventional exercises for shoulder rehabilitation focus on strengthening and endurance training of the dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder in order to decrease the stress placed on the passive structures of the joint. Treatment programs include capsular stretching (especially the posterior capsule in overhand throwers), rotator cuff strengthening, multidirectional strengthening, dynamic stabilization techniques, plyometrics, open and closed kinetic chain exercises, and concentric and eccentric exercises.13,16–26 While these traditional therapies are necessary, the only way to imitate the forces and torques placed on the joints of the upper extremity and trunk during softball is by pitching and throwing.21

Conventional rehabilitation exercises used for the injured throwing athlete should include a structured throwing program. The purpose of an interval throwing program (ITP) is to return an injured player to preinjury status through a step-wise functional progression without overstressing the healing tissues. Throwing too much too soon goes against this principle and may cause an athlete to heal more slowly.21 Few examples of ITPs exist in the literature.13,16,21,27–29 Most are based merely on how quickly the authors believe an athlete should return to play. Axe et al21,29 have developed 2 ITPs based on data that consider the stresses placed on the athlete during a game situation as well as the type of injury a player has incurred. One of these programs is devised for Little League (9- to 12-year-old) baseball pitchers, and the other was designed for baseball pitchers at all other levels (Senior Little League to professional).21,29 We found no published data-based ITPs for fast-pitch softball players. In addition, we found no published data-based ITPs designed for position players other than the pitcher for baseball or softball at any level.

The culmination of an ITP is a simulated game. A true simulated game is derived from game-specific data of athletes at a particular level of competition (ie, college). The injured athlete must complete this simulated game before being cleared to return to competition. No descriptions of data-based simulated games have been published for softball players at any position. Coleman et al30 reviewed data collected from 3 professional baseball seasons in order to determine an injured pitcher's readiness for return to play. They used a simulated game that included number of pitches per inning, innings pitched per game, time between innings, and preinjury pitch mix utilized by the player in question.30 While the simulated game is excellent for testing a pitcher for game worthiness, it does not include a step-wise progression building toward the simulated game.21

The purpose of our study was to develop data-based ITPs followed by simulated games for collegiate fast-pitch softball players at all positions. These ITPs are based on the game data collected, rules of the game at the collegiate level, and the type of injury sustained.

METHODS

Data Acquisition

We collected pitching data for the pitcher's throwing program over 220 half-innings and 2785 pitches of NCAA softball during a single season. We recorded number of pitches per inning and per game. We used these data and NCAA softball rules (eg, innings per game, pitcher to home plate distance)5 to construct the pitcher's throwing program.

We collected catcher data over 219 half-innings. We recorded time in the squat stance, throws to the pitcher (43 ft [13.11 m]),5 throws to base (throws involving an attempt to put out an opposing runner), distance of throws to base, the intensity (percentage effort) of throws to base, and sprints to first or third base (60 ft [18.29 m]).5 We then assessed the time in the squat stance, throws to the pitcher, throws to base, and sprints by number per inning and number per game. We calculated the mean distance of throws and intensity of throws. Intensity of throws was estimated by the observer based on the game situation (eg, live plays were always recorded as 100%). We used these data and NCAA softball rules5 to construct the catcher's throwing program.

We collected the infielder and outfielder data over 219 half-innings. We recorded number of throws, distance of throws, and intensity of throws for each position. We calculated the mean distance of throws and intensity of throws and assessed the number of throws per inning and per game. We then constructed the infielder and outfielder throwing programs from these data and NCAA softball rules.5

Data Management

In order to construct the ITPs, we considered dimensions of the collegiate-level softball field, the data we collected, the types of injuries found in collegiate softball players, and a general understanding of tissue healing times and properties. We developed separate programs for the catcher and pitcher because the stresses placed on these players during a game situation vary greatly from those placed on infielders and outfielders. In addition, we constructed one program for the infielders and one for the outfielders. These programs reflect the maximums of all infielders and outfielders, respectively. This type of design allows an infielder to be cleared for play at any position in the infield and the outfielder to be cleared for play at any position in the outfield. We used the ranges, instead of means, to devise the throwing programs because in any given contest, the athlete may have to perform at the maximum level. Therefore, the simulated games represent the maximums at each position.

RESULTS

Pitchers

During data collection, no pitchers were removed from a game due to injury, and no other pitching changes were noted within games. However, in all recorded cases, pitchers were replaced between doubleheaders. The pitchers averaged 12.7 pitches per inning and 89.6 pitches per game. The range of pitches was 60 to 141 per game; 2785 pitches were recorded. We recorded no pick-off attempts during data collection because, unlike baseball, the runners in softball are not allowed to lead off.

Catchers

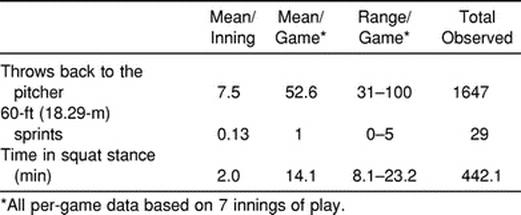

We found the catchers to be in the squat stance for an average of 14.1 minutes. They threw to the pitcher an average of 52.6 times per game. Live throws, or throws to base, were made an average of 3.2 times per game at an average distance of 65.7 ft (20.03 m) and an average effort of 97.65%. In addition, we calculated 1 sprint of approximately 60 ft (18.29 m) for each game (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Softball Catchers' Data (Throws to Base Not Included)

Table 2. Softball Fielders' Data

Fielders

The shortstops averaged the most throws per game (6.3). The highest average effort of throws (93.1%) was exhibited by the third basemen, who only threw the ball an average of 4.3 times per game, while the second basemen averaged the lowest average effort per throw (80.6%). The longest throws (average, 63.8 ft [19.45 m]) were from the third basemen, while the shortest throws (46.2 ft [14.08 m]) were made by the second basemen. Even though they averaged the shortest throwing distances, the first and second basemen had the largest ranges (10 to 110 ft [3.05 to 33.53 m] and 10 to 130 ft [3.05 to 39.62 m], respectively) (see Table 2).

The left fielders averaged the most plays (2.8) per game, and had a low average distance of throws (77.5 ft [23.62 m]), a small range of distances of throws (10 to 140 ft [3.05 to 42.67 m]), and the lowest average effort (87.8%). Right and center fielders had larger and more similar average distance of throws (87 and 85.8 ft [26.52 and 26.15 m], respectively) and ranges of distance of throws (25 to 165 ft [7.62 to 50.29 m] and 20 to 175 ft [6.10 to 53.34 m], respectively) (see Table 2).

Program Design

Within a given ITP, an athlete progresses from no throwing to the volume and intensity present in a game situation. Each program includes long tosses designed to increase endurance and strength throughout the progression. All long tosses should be thrown with the “crow-hop” method, which employs a hop, skip, and throw to incorporate the use of the lower extremities and trunk. The “crow-hop” minimizes the risk of improper mechanics and enables the body to gain momentum from the lower extremities and trunk.28 Total throwing volume (number of throws × distance × intensity) is progressed slowly throughout each program.21 During each step and portion of each step of the throwing programs, one of the 3 components of the total throwing volume is increased, thereby increasing the total throwing volume. For instance, the total throwing volume of the field practice in step 3 of the infielder's program is (5 × 60 × .75) + (10 × 75 × .75) = 787.5, while the total throwing volume of the field practice in step 4 is (5 × 60 × .75) + (5 × 84 × .75) + (5 × 120 × .75) = 990. The pitching program consists of 4 phases; the catching program has 3 phases; and the infielder and outfielder programs have 2 phases each.

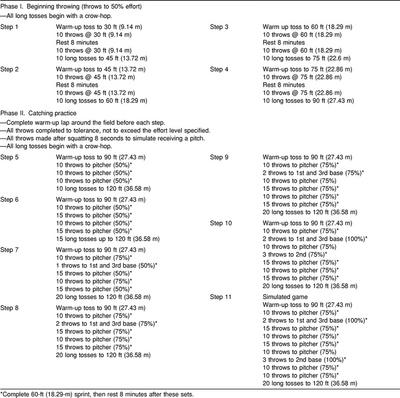

The 4 phases of the pitching program are early throwing, initiation of pitching, intensified pitching, and a simulated game. We designed these phases to slowly progress the loads applied to the throwing arm. The program begins with short throws to tolerance (up to 50% effort) as well as long tosses up to 120 ft (36.58 m) to increase arm strength and endurance (early throwing). No pitching is instituted in this phase. The next phase, initiation of pitching, includes pitching up to 75% effort as well as continuation of the long-toss component. The intensified pitching stage takes the pitcher from the initiation of pitching to the simulated game. Off-speed pitches (curve, rise, drop, change-up) and rest intervals, which correspond with a game situation, are incorporated in this phase. The pitcher chooses the mix of pitches that compare with her preinjury pitch preference. The final stage of this phase is for the athlete to pitch batting practice. Before being cleared for return to play, the pitcher pitches a simulated game. The simulated game is based on the maximums of all inning and game data collected (Appendix A).

Appendix A. Softball Pitcher's Program

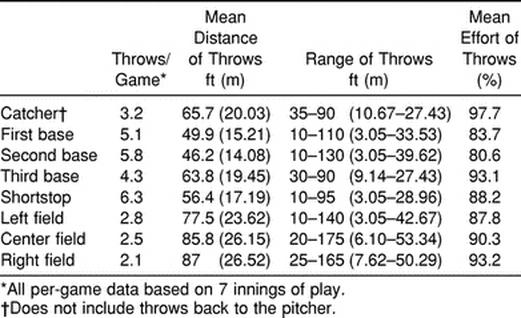

The catcher's program has 3 phases: beginning throwing, catching practice, and a simulated game. First, the catcher throws only up to 50% of perceived effort, with long tosses to 90 ft (27.43 m). This phase (beginning throwing) allows the catcher to build the strength and endurance that are necessary for intensified activity. With progression, sprints are incorporated as in a game situation when backing up throws. Additionally, the athlete simulates throwing to second base as well as throwing the ball back to the pitcher (catching practice). Eventually, the athlete completes a simulated game before she is cleared for return to play (Appendix B).

Appendix B. Softball Catcher's Program

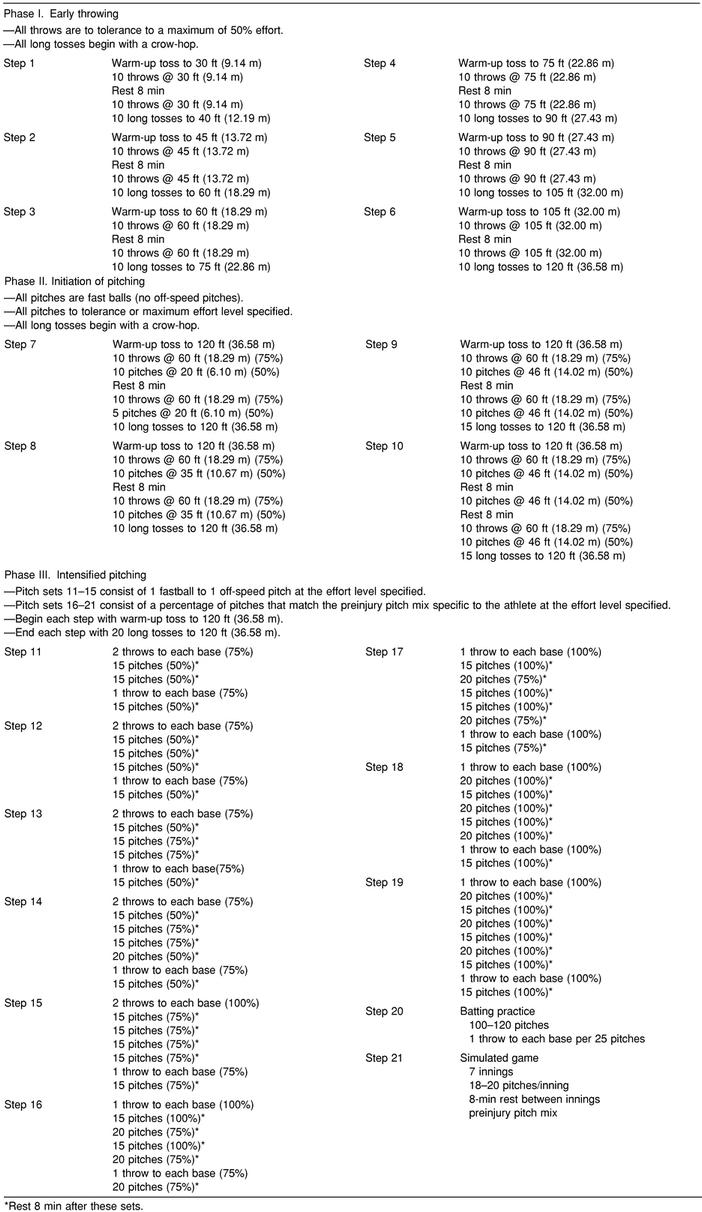

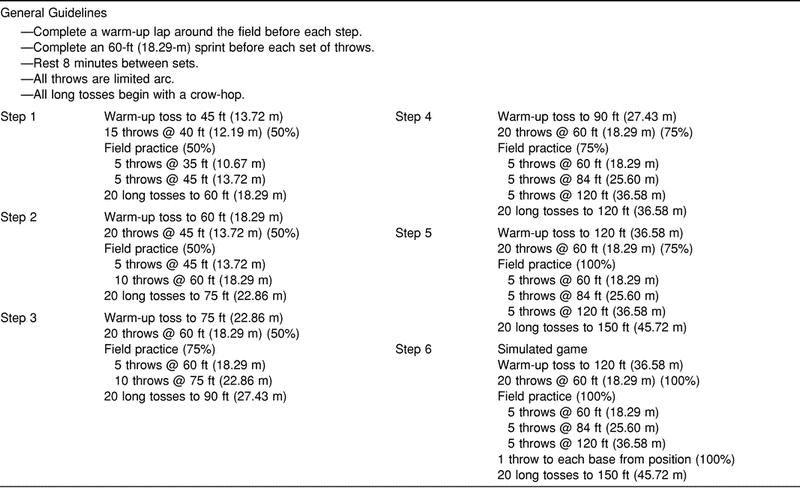

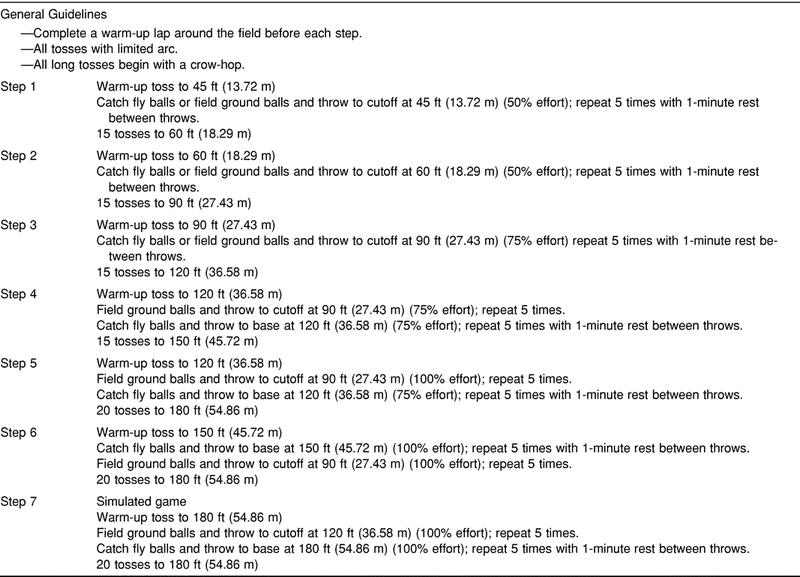

The infielder and outfielder programs consist of only 2 phases: throwing and a simulated game. The infielder's throwing phase begins with short throws at 50% of maximum intensity and long tosses up to 60 ft (18.29 m). It then progresses, over 5 steps, to throws at 100% effort and long tosses up to 150 ft (45.72 m). Fielding practice and sprints are included in the program (Appendix C). Before returning to play, the athlete must complete the simulated game. The outfielder's throwing program consists of the return-to-throwing phase and a simulated game. Initially, the fielders only throw up to 50% of maximum effort and up to distances of only 60 ft (18.29 m). The final stage includes long tosses of up to 180 ft (54.86 m) and throws of up to 100% effort. Fly and ground balls are included in all stages, and rest intervals correspond with rest between innings (Appendix D). The final step is for the athlete to complete a simulated game.

Appendix C. Softball Infielder's Program

Appendix D. Softball Outfielder's Program

PROGRAM PROGRESSION

Soreness Rules

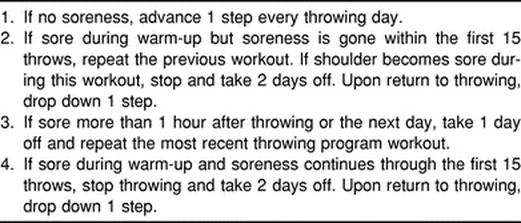

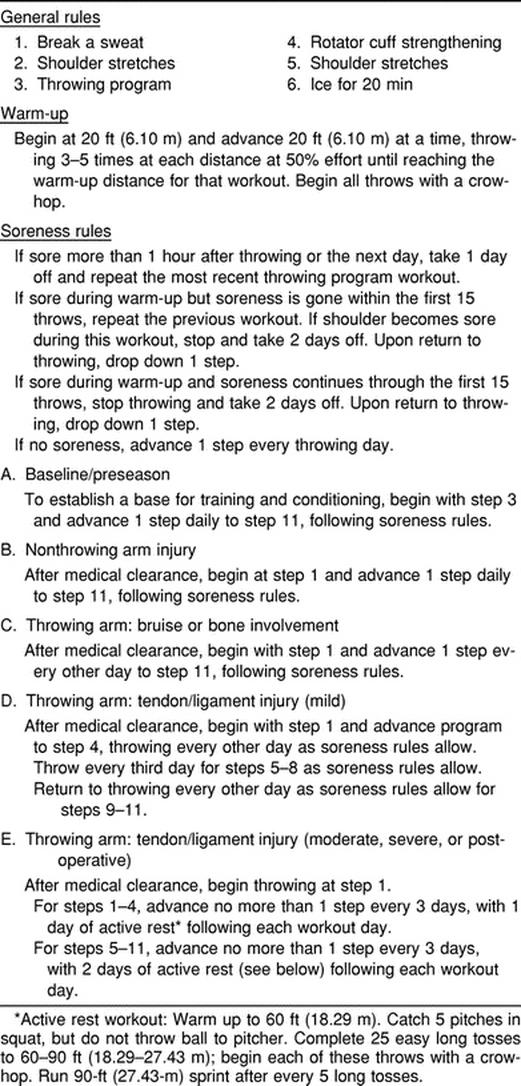

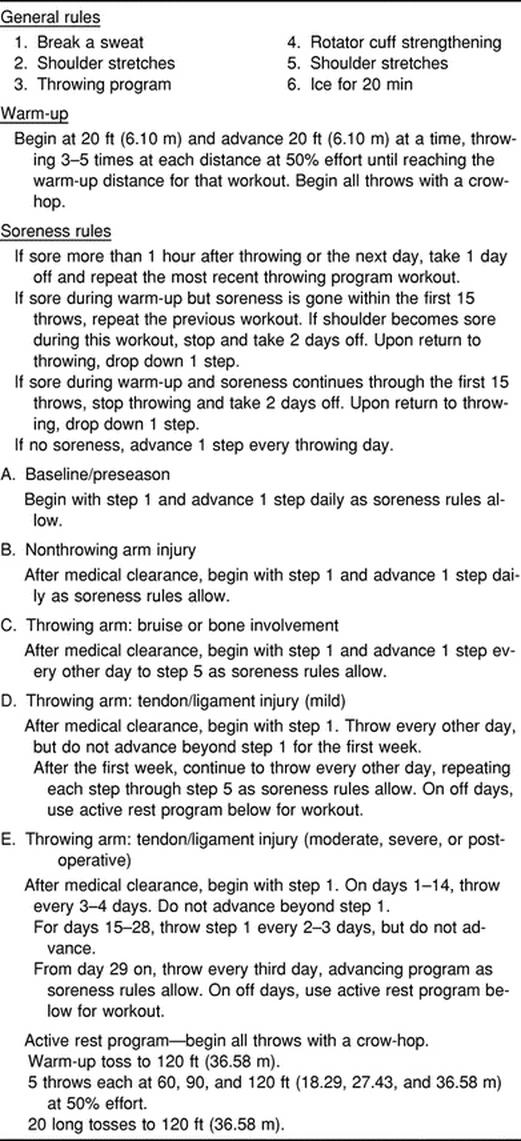

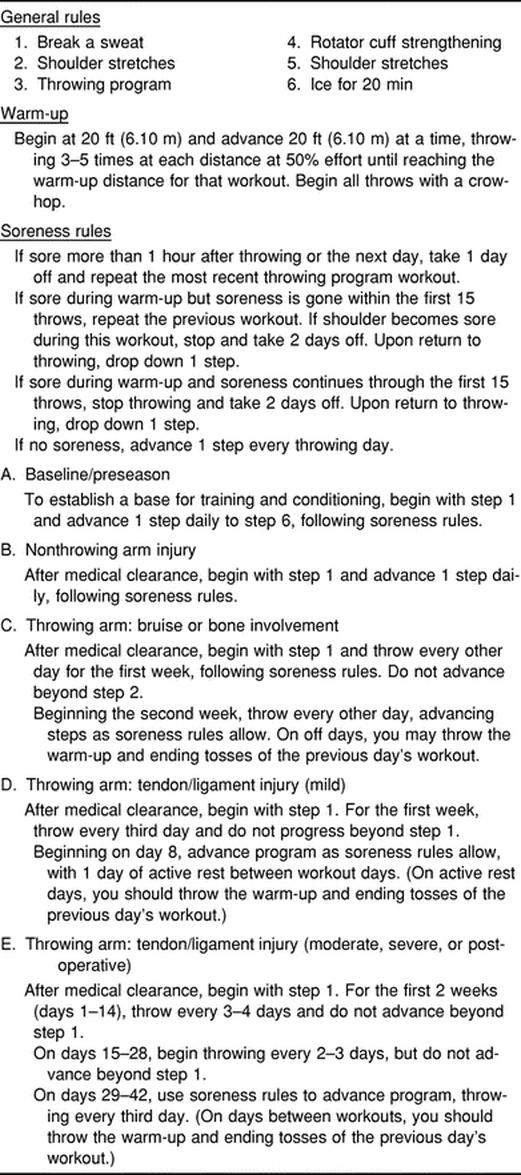

Axe et al21 defined soreness rules (Table 3) for baseball pitchers in an ITP. Their rules allow the athlete to modify progression according to symptoms. Athletes may heal at different rates and, therefore, need to progress at different paces. The soreness rules are used to prevent overstressing the soft tissues during progressive return to play. They dictate when an athlete may progress to a higher step, remain at the same step, or drop down one step. They also help dictate the amount of rest time indicated between throwing days.21

Table 3. Soreness Rules

Injuries

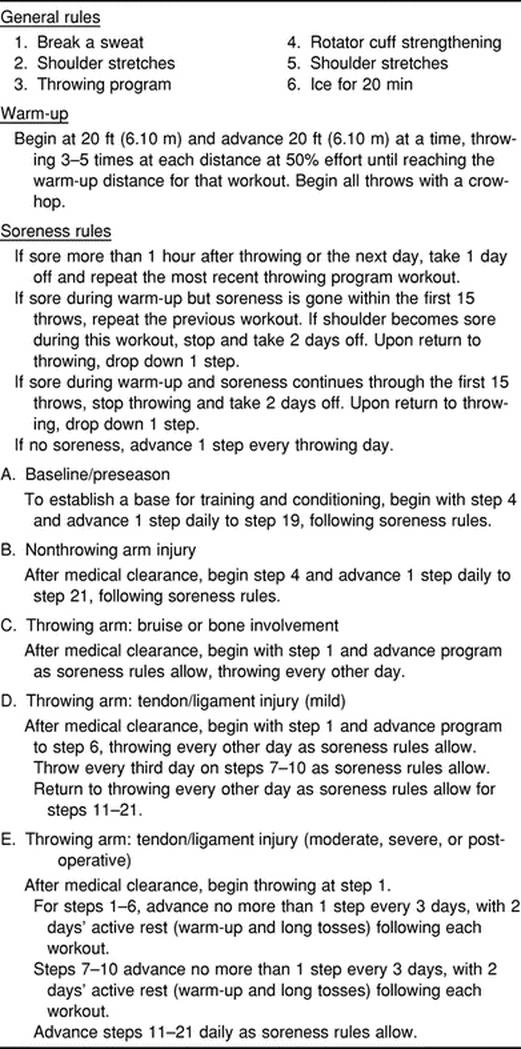

In the return-to-play phase of rehabilitation, we use an injury classification scheme to modify the program: specifically when to begin throwing, how many days of rest are needed between days of throwing, and how quickly the athlete may progress through the ITP. The classification is hierarchical. Injuries to body parts other than the throwing arm require the least modification, followed by injuries to the throwing arm that do not involve the joints (bruises), mild injuries to the throwing arm that involve the joints (tendinitis), and injuries to the throwing arm that are severe (postoperative, torn ligament) (Appendices E,F,G,H). Before initiation of throwing, the physician and any rehabilitation specialist involved must determine that the healing structures are ready to withstand the stresses of throwing.21 Once throwing has begun, the athlete can progress as the classification of her injury and the soreness rules allow.

Appendix E. Softball Pitcher's Instructions

Appendix F. Softball Catcher's Instructions

Appendix G. Softball Infielder's Instructions

Appendix H. Softball Outfielder's Instructions

DISCUSSION

No data-based ITPs developed for collegiate softball players at any position have previously been published. Furthermore, no published data-based ITPs for positional players other than pitchers have been developed for baseball or softball. The ITP being suggested is not intended to replace traditional rehabilitation but instead to augment those treatments. Within rehabilitation programs, it is imperative to include a functional progression that allows a speedy and safe return to sport.

Despite the cited differences between baseball and softball, the upper extremity injuries found in softball players other than the pitcher (overhead throwers) are similar to those of baseball players.4,31 The shoulder injuries that occur in overhead throwers include, but are not limited to, impingement,7,20,23–26,32 instability,7,8,13,20,23–26 undersurface rotator cuff tears,7,8,16,20,23,25,26 and glenoid labrum tears.7,8,16,20,23,25,26 Common elbow problems in overhead throwers are medial epicondylitis,33,34 partial or complete tearing of the flexor musculature,34 osteochondral defects of the capitellum,20,26,33,34 ulnar collateral ligament laxity or rupture,20,26,27,33,34 olecranon osteophytes and loose bodies,20,26,32,33 and ulnar neuritis.20,26,33,34

Softball pitchers do, however, have specific injury patterns linked to the dynamics of the windmill pitch. Most of these injuries occur in the shoulder and elbow. Shoulder injuries include instability,13,14 rotator cuff tendinitis,15 bicipital tendinitis,14,15 subscapularis strain,14 pectoralis strain,14 biceps-labrum degeneration,13,14 and trapezius strain.15 Elbow injuries include ulnar neuritis,13,14 ulnar collateral ligament damage,14 and tendinitis.15

The injuries to softball pitchers are a result of the forces and torques imparted upon the upper extremity during the windmill pitch. The forces, torques, and speed with which the windmill pitch occurs are responsible for the incidence and type of injuries sustained.14 The athlete must be rehabilitated successfully to withstand the listed values imparted on the upper extremity during windmill pitching.

Clearing an athlete to begin the ITP is the responsibility of the health care professionals as a team. They must be sure that the healing tissues can withstand the forces applied to the joints during the early stages of the throwing program. The athlete's personal healing characteristics, the incurred injury, the treatment being administered, and the player's softball position all dictate the decision of the health care team.21 The early stages of the throwing programs only allow the athlete to throw to tolerance but at no greater effort than 50%. Baseball players are not usually accurate in attempting to duplicate a desired effort level. Fleisig et al35 studied 27 healthy college baseball pitchers. When requested to throw at 50% effort, the pitchers averaged ball speeds of 85% of their maximum and forces and torques of 75% of their maximum. When requested to throw at 75% effort, the ball speeds reached 90% and the forces and torques reached 85%.35 These findings indicate the need for early supervision of the program by the rehabilitation professional or athletic trainer.

Our goal was to develop data-based ITPs for collegiate-level softball players in all positions. We intend these programs to be used as functional progressions within traditional rehabilitation programs for injured softball players. In addition, the programs are useful for training and conditioning regimens used during the off-season and preseason. Our objective is for the programs to be useful for all health care professionals, coaches, and their respective athletes. The programs are designed to allow the athlete and coach or athletic trainer to continue the program once formal rehabilitation has ended. The throwing or pitching athlete is slowly progressed from no throwing to game situation levels of throwing through a gradual increase in intensity and total throwing volume step by step. The goal we are proposing for the ITPs for collegiate softball players is to promote efficient and safe return to sport.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chris Kuchta and Robbin Wickham, MPT, for their assistance.

REFERENCES

- National Collegiate Athletic Association NCAA Online. Available at: http://www.ncaa.org/participation_rates/1982–99_overall.html. Accessed February 8, 2001.

- National Collegiate Athletic Association The Research Staff. Available at: http://www.ncaa.org/participation_rates/1998–99_women'sparticpationrates.html. Accessed February 8, 2001.

- The National Collegiate Athletic Association News NCAA Injury Surveillance System. http://www.ncaa.org/news/19990927/active/3620n07.html. Accessed February 8, 2001.

- Powell J W, Barber-Foss K D. Sex-related injury patterns among selected high school sports. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:385–391. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280031801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collegiate Athletic Association . NCAA 2000 Softball Rules. National Collegiate Athletic Association; Indianapolis, IN: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Collegiate Athletic Association . NCAA 2000 Baseball Rules. National Collegiate Athletic Association; Indianapolis, IN: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meister K. Current concepts: injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete, part one: biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:265–275. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280022301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altchek D W, Dines D M. Shoulder injuries in the throwing athlete. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:159–165. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe F W, Moynes D R, Tibone J E, Perry J. An EMG analysis of the shoulder in pitching: a second report. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:218–220. doi: 10.1177/036354658401200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe F W, Tibone J E, Perry J, Moynes D. An EMG analysis of the shoulder in throwing and pitching: a preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11:3–5. doi: 10.1177/036354658301100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffet M W, Jobe F W, Pink M M, Brault J, Mathiyakom W. Shoulder muscle firing patterns during the windmill softball pitch. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:369–374. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford D. An Introduction to Softball Pitching Mechanics. Wm C Brown; Dubuque, IA: 1990. pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hurd W. Special population: rehabilitation considerations for the female softball player. Sports Med Update. 1999;14:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Barrentine S W, Fleisig G S, Whiteside J A, Escamilla R F, Andrews J R. Biomechanics of windmill softball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms at the shoulder and elbow. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:405–415. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.6.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loosli A R, Requa R K, Garrick J G, Hanley E. Injuries to pitchers in women's collegiate fast-pitch softball. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:35–37. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas A M, Zawacki R M, McCarthy C F. Rehabilitation of the pitching shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:223–235. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk K E, Arrigo C A, Andrews J R. Closed and open kinetic chain exercise for the upper extremity. J Sport Rehabil. 1996;5:88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzullo D J, Karas S, Irrgang J J. Functional plyometric exercises for the throwing athlete. J Athl Train. 1995;30:22–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lephart S M, Pincivero D M, Giraldo J L, Fu F H. Current concepts: the role of proprioception in the management and rehabilitation of athletic injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:130–137. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisig G S, Barrentine S W, Escamilla R F, Andrews J R. Biomechanics of overhand throwing with implications for injuries. Sports Med. 1996;21:421–437. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199621060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axe M J, Wickham R, Snyder-Mackler L. Data-based interval throwing programs for Little League, high school, college and professional baseball pitchers. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2001;9:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen R L, Callis M, Potts J, Shall L M. A modified internal rotation stretching technique for overhead and throwing athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21:216–219. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.21.4.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield R, Hawkins R, Dillman C J, Atkins J, Hagerman G. Rehabilitation for the overhead athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18:433–441. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk K E, Arrigo C. Current concepts in the rehabilitation of the athletic shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18:365–378. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.1.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister K, Andrews J R. Classification and treatment of rotator cuff injuries in the overhead athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18:413–421. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T E. Cleveland Clinic Foundation; Cleveland, OH: Shoulder and elbow problems occurring with throwing in softball or baseball. Presented at: Sports Medicine for the Athletic Trainer. June 20-21 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Azar F M, Andrews J R, Wilk K E, Groh D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:16–23. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280011401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk K E, Arrigo C A. Interval sport programs for the shoulder. In: Andrews J R, Wilk K E, editors. The Athlete's Shoulder. Churchill Livingstone; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 669–671. [Google Scholar]

- Axe M J, Snyder-Mackler L, Konin J G, Strube M J. Development of a distance-based interval throwing program for Little League-aged athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:594–602. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman A E, Axe M J, Andrews J R. Performance profile-directed simulated game: an objective functional evaluation for baseball pitchers. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1987;9:101–105. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1987.9.3.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J R, Carson W G, Jr, McLeod W D. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:337–341. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibone J E, Jobe F W, Kerlan R K, et al. Shoulder impingement syndrome in athletes treated by an anterior acromioplasty. Clin Orthop. 1985;198:134–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar F M, Wilk K E. Nonoperative treatment of the elbow in throwers. Oper Tech Sports Med. 1996;4:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jobe F W, Nuber G. Throwing injuries of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1986;5:621–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisig G S, Barrentine S, Zheng N. Conference Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Meeting of the American Society of Biomechanics. Atlanta, GA: Kinematic and kinetic comparison of full-effort and partial-effort baseball pitching. October 17-19 1996. [Google Scholar]