Abstract

Objective: To gain an understanding of the professional socialization experiences of certified athletic trainers (ATCs) working in the high school setting.

Design and Setting: A qualitative investigation using a grounded theory approach was conducted to explore the experiences related to how ATCs learned their professional role in the high school setting.

Participants: A total of 15 individuals (12 ATCs currently practicing at the high school level, 2 current high school athletic directors who are also ATCs, and 1 former high school ATC) participated in the study. The average number of years in their current position for the 12 currently practicing ATCs was 10.16 ± 7.44, with a range of 2 to 25 years. The 2 athletic directors averaged 5.5 years of experience in their roles, and the former high school athletic trainer had worked in that setting for 1 academic year.

Data Analysis: The interviews were transcribed and then analyzed using open, axial, and selective coding. Peer debriefing, member checks, and triangulation were used to establish the trustworthiness of the study.

Results: Informal learning processes were discovered as the overarching theme. This overarching theme was constructed from 2 thematic categories that emerged from the investigation: (1) an informal induction process: aspects of organizational learning, and (2) creating networks for learning.

Conclusions: Informal learning is critical to the professional socialization process of ATCs working in the high school setting. Because informal learning hinges on self-direction, self-evaluation, reflection, and critical thinking, the findings of this study indicate that both preservice and continuing education should attempt to foster and enhance these qualities.

Keywords: informal role induction, learning networks, organizational socialization, self-evaluation, reflection, critical thinking

Professional socialization is a process by which individuals learn the knowledge, skills, values, roles, and attitudes associated with their professional responsibilities.1 Socialization is considered to be a key component of professional preparation and continued development in health and allied medical disciplines2,3 and has been investigated in medical education,4,5 nursing,6,7 occupational therapy,8 and physical therapy.9

Professional socialization is typically exemplified as a 2-part developmental process that includes experiences before entering a work setting (anticipatory socialization) and experiences after entering a work setting (organizational socialization).10 The first process, anticipatory socialization, refers to experiences such as one's formal training as an undergraduate or graduate student, background as an employee in another setting such as an Emergency Medical Technician, or prior experience as a volunteer with an organization such as the American Red Cross. Organizational socialization refers to experiences such as in-service education and mentoring. The organizational socialization phase of professional socialization can be divided into 2 parts: (1) a period of induction, and (2) role continuance.10 Induction experiences take many forms. For example, induction processes can be either very formalized (ie, requiring employees to attend specific orientations or instructional sessions) or very informal (ie, no orientation). Additionally, induction processes may be either sequential, requiring specific skills to be learned at specific times during the initial periods of a job, or random, having no time frame for the development of various skills within the organization. Role continuance, on the other hand, focuses on adjusting to the organizational demands over time and continually learning the nuances of a given role and developing professionally. While athletic training has given a great deal of attention to the anticipatory socialization by way of the professional preparation process, there is a paucity of research related to organizational socialization.

Organizational socialization relates to how individuals adapt to their new roles and learn about what is acceptable practice in dealing with the demands of their work. For example, the organizational socialization can be very structured, such as having an athletic director orient a new employee in a very systematic manner, or this process can be unstructured, leaving the employee to ask questions of other employees as various situations arise. Understanding the organizational aspects of professional socialization allows the discovery of the necessary aspects of professional development in a work setting and can serve to improve both athletic training education and continuing education strategies. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to explore the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers (ATCs) in the high school setting in order to gain insight and understanding into how they initially learned and continued to learn their professional responsibilities in an organizational setting.

METHODS

Because the purpose of the project required an exploration of the actual experiences of ATCs in the high school setting and how the setting influenced their learning, qualitative methods were employed. The fundamental objective of qualitative research is to gain insight into and understand the meaning of a particular experience,11,12 and the context that influences the meaning,13 rather than drawing firm conclusions. Qualitative research is also well suited to study processes13 such as professional socialization.

In qualitative research, the protection of the participants' anonymity is paramount. Therefore, audiotape recordings of interviews were transcribed and labeled with pseudonyms that are used at various locations in the manuscript. Moreover, at the completion of the study, the audiotapes were destroyed, but the transcripts were maintained using the established pseudonyms. Before data collection, appropriate institutional review board approval was received.

With qualitative methods, the researcher is the primary “instrument” for data collection and analysis, and extreme sensitivity is given to the nature and perspectives of human participants. A researcher's perspective, however, can shape the analysis and interpretation of the qualitative data. My perspectives about the high school setting were shaped in 2 ways. First, I was formerly employed as a clinical high school ATC and interacted with coaches, athletic directors, and athletes and their parents. Second, at the time of data collection and analysis, I was a faculty member in a Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP)-accredited program that used several high school sites as clinical education experiences for the athletic training students. Entering this study, I believed that professionals are not simply products of their work environments but rather active participants in their professional development and that this process continues throughout their careers. This line of thought is consistent with symbolic interactionism, which is often used as a theoretic basis for grounded theory studies.14

Participants

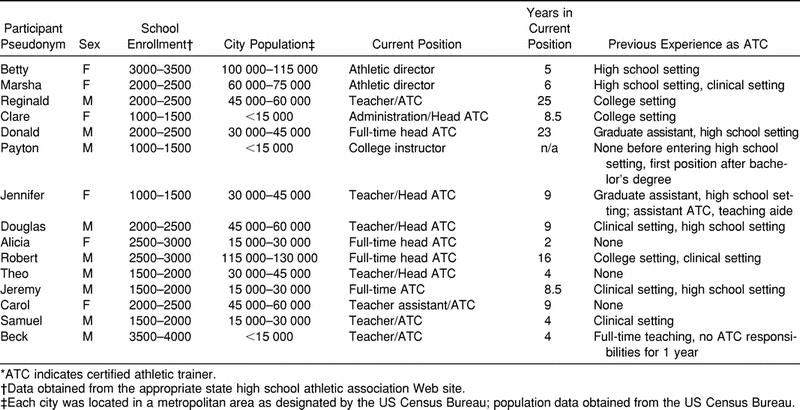

A total of 15 individuals (12 ATCs currently practicing at the high school level, 2 current high school athletic directors who are also ATCs, and 1 former high school ATC) participated in the study. The average number of years in their current position for the 12 currently practicing ATCs was 10.1 ± 7.44, with a range of 2 to 25 years. The 2 athletic directors averaged 5.5 years of experience, and the former high school ATC had worked in that particular setting for 1 year before entering graduate school. The athletic directors and former high school ATC were included in order to cross-reference, or triangulate, the perspectives of the currently practicing ATCs. Six participants were women and 9 were men. The participants represented 3 different midwestern states. Participants were initially purposefully selected: that is, I recruited volunteers whom I knew and who agreed to interviews. I then asked these individuals for suggestions of other ATCs who might be willing to participate. The remaining individuals were contacted via either e-mail or phone and agreed to interviews. Before the interviews, participants were required to review and sign an informed consent form. The Table identifies other pertinent participant demographic information.

Table 1.

Participants' Demographic Information and ATC* Experience

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected using semistructured interviews. Each interview incorporated several key questions or open-ended statements, including the following:

Describe your first few years of being an ATC at the high school level.

How did you learn your role and professional responsibilities at the high school level?

What has been your greatest challenge at the high school level, and how did you learn to deal with it?

What do you like best, or what are the good things about your current position?

What aspect of your job do you feel least satisfied by?

What is, or how would you describe, your professional mission?

What motivates you on a daily basis?

What advice might you give to an ATC just about to enter the high school setting for the first time?

Because both athletic directors were former ATCs practicing in the high school setting, they were asked to reflect on their experiences as an ATC by answering questions 1 through 4 and question 8. Additionally, they were asked to describe the priorities of the athletic department, the role of ATCs in the high school setting, and the challenges that ATCs face in the high school setting.

The interviews ranged in length from approximately 35 to 105 minutes. Eight interviews were conducted by phone, and 7 interviews were conducted in person, based on feasibility and availability. Participants gave advanced written and verbal consent to tape record the interviews. The tape-recorded interviews were then transcribed and analyzed using a grounded theory approach. Data were collected until theoretic saturation was achieved.15

The grounded theory approach, as discussed by Glaser and Strauss,16 is helpful for generating theory (a set of explanatory concepts) based on the data collected. I specifically used open, axial, and selective coding procedures documented by Strauss and Corbin.15 Raw data were analyzed inductively, and incidents or experiences related to the phenomenon under investigation were identified and labeled as a particular concept. This type of coding strategy is described as “creating tags,” and the purpose is to produce a set of concepts that represents the information obtained in the interview.17 Identifying these concepts and placing them into like categories based on their content completed the formal open-coding process. Relating categories with any subcategories that might exist and examining how one category related to another completed the axial-coding process. Selective coding involved integrating the categories into a larger theoretic scheme and organizing the categories around a central explanatory concept, specifically, the proposition that informal learning processes were critical to the successful professional socialization of ATCs in the high school setting.

Trustworthiness

Several techniques were employed in order to establish trustworthiness of the data collection and analysis, including peer debriefing, data-source triangulation, and member checks. A peer debriefing was completed by having an athletic trainer with a formal education in qualitative methods (a minimum of 3 qualitative research methodology courses at the doctoral level) review the documented concepts and thematic categories for relevance, consistency, and logic. Moreover, the reviewer examined the interview questions in each transcript to determine if they were “leading” in nature. The textual data from any questions identified as being leading were not included in the analysis. The reviewer was in agreement with the findings based on the purpose of the study and even suggested other concepts that would strengthen one particular category.

Data-source triangulation, which is cross-checking perspectives,18 was obtained by interviewing current high school athletic directors and a former high school ATC. Member checks were completed electronically by e-mailing the results to 5 participants and allowing them to comment on the thematic categories. Three individuals responded, agreed with the results, and had no further input, indicating no misinterpretation of the professional-socialization process that emerged from this study. On an informal basis, I also explained the results to 4 other participants, and they were in agreement with the findings.

RESULTS

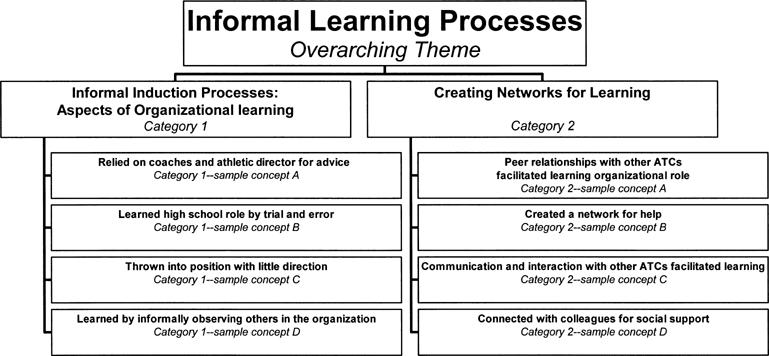

The concepts identified during the open coding were organized into 2 categories that gave insight into the professional socialization process: (1) an informal induction process, aspects of organizational learning, and (2) creating networks for learning. The Figure provides a conceptual framework and identifies representative sample concepts and the categories into which they were placed. The axial coding allowed for making connections among categories and understanding the setting that influenced the socialization process. The selective-coding process allowed for the discovery of an overarching theme or informal learning processes that integrated the categories and gave insight into the resultant proposition that informal learning processes are critical to the successful professional socialization of ATCs in the high school setting.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual framework of the qualitative data organization is presented. Note that the concepts organized into the categories are representative samples of the concepts coded in the margins of the transcripts.

An Informal Induction Process: Aspects of Organizational Learning

Certified athletic trainers entering the high school level reported extremely nonstructured, informal processes relative to learning the full extent of their professional responsibilities within the organization. Peer relationships drove most of the learning at the high school level in that ATCs were able to gain an understanding of their responsibilities by obtaining feedback from the coaches that they worked with and, although in some instances to a lesser extent, their athletic directors (Figure, sample concept A, category 1). For example, Theo stated that learning the “ins” and “outs” of the organization came from interactions with the coaching staff, specifically the football coach:

He's an extremely intelligent human being and he knows the politics of the system and he knows…everything about the “ins” and the “outs” of the school district, and schools in general, so he was very helpful in getting me to learn more about the after-school athletic type aspect [of my job].

Supporting this claim, Alicia stated that “the football coach kind of showed me the ropes…,” indicating that the positive relations with the coaching staff influenced her organizational learning when she initially entered the high school setting.

Based on the interview data, the peer relationships may have allowed for informal learning because the organizations were focused on academics and on the health and welfare of the students. That is, during the interview process, there were occasional discussions regarding minor conflicts between staff members, but absent from the interviews were identifiable power struggles that deterred high school ATCs from achieving their professional mission of providing quality health care. In fact, there was evidence to suggest that a common priority at each of the organizations allowed ATCs, coaches, and athletic directors to coexist in a collegial manner. For example, when asked about the organizational priorities, Theo stated:

Sports…definitely…helps define the high school. So I think the administration accepts that…[but] definitely the school's number one mission is the education of its students. Our athletic department is very strict on its maintaining of the academic requirements for eligibility…we actually started an at-risk after school program for any kid who is in danger of failing a class… They get help with any questions they may have and they are required to do their homework before they go to practice or any game. I firmly believe I have one of the best coaching staffs to be able to work for as far as the kids come first and the victories don't.

Both athletic directors interviewed for this project supported the ATC's comments:

Well, the priority certainly…[is] the student-athletes, students first. So academics is very important to us here at High School A. We watch and monitor that very closely and all our coaches have that mindset. Then, certainly, the second would be the safety issue. That comes from my athletic experience, prevention. We are very attuned to proper weight training and nutrition. We constantly talk to student-athletes about diet, sleep, healthy choices for their bodies, [both] mentally and physically. Then, we feel that winning will take care of itself.

Academics are first and foremost in my mind. And I say athletics is an educational opportunity and so what we try to do is make …our mission [reflect this priority]. I make all the decisions based on that particular mission.

Participants in this study were socialized into their role in the high school setting using individual and informal tactics, meaning that they were often functioning independently and relying on trial-and-error learning (Figure, sample concept B, category 1). Moreover, many participants explained that they learned through the observation of others (Figure, sample concept D, category 1). For example, Marsha stated, “I am very fortunate that I've been around a lot of people who have very good people skills, and I feel that I picked up on that. I think athletic trainers are very adaptable to being flexible and can learn some of the ropes just by watching.”

Additionally, with the exception of working closely with coaches and other staff, there was no formalized mentoring in place to facilitate learning of their role. In short, the ATCs were expected to enter the setting and immediately begin functioning in their role in an independent manner (Figure, sample concept C, category 1).

There appeared to be no detectable timeline to the professional-socialization process relative to specific events or professional experiences, except that when each of the individuals entered the setting, there was a small period of adjustment. The induction process during this time was extremely informal. For the high school ATCs who obtained a position immediately after completing their undergraduate degree (Carol, Theo, Alicia, and Payton), much of the adjustment was related to moving from a setting that had a great deal of supervision to one with little supervision. For example, Theo mentioned:

[Although] the first year was pretty calm for the most part, [I] just tried to get used to things and being on my own without having a supervisor that could help me out with whatever I needed help with.

Even Reginald, reflecting on his first-year experience, stated, “I knew what I was doing [relative to] athletic training …but I didn't know all the ‘ins and outs’ and the politics.”

Consistently, participants identified the necessity of setting up their health care system in the high school setting and learning how best to communicate with other staff (coaches and athletic directors), parents, and student assistants and how to meet the demands of providing health care to such a large athletic population. Learning this role was informal and often described as a trial-and-error process. For example, Alicia reflected on initially entering the high school setting and stated:

Actually, I learned by trial and error. There really wasn't anyone [to facilitate my learning]. The other person that I worked with started the same day I did, so neither of us had any idea, we just kind of went into it with what knowledge we had of what a college [athletic] training room was like and kind of took that into our own [facilities]. Obviously we had to modify certain things, like getting prescriptions for modalities and things like that.

Similarly, when asked about how she initially learned her role in the high school, Jennifer commented on the induction period and stated that “unless there was previously an athletic trainer within the organization, there would be nobody to orient a newcomer to [his or her] role.” Confirming this theme, Robert stated, “I was not given any type of orientation or didn't meet any of the coaches. I was given a set of keys and told ‘good luck.’ I was on my own…My budget was woeful…so it was tough that first year….” Donald added, “I think a lot of [learning of the job] is trial and error. There are a lot of things that I don't do now that I did years ago and I thought, well, that didn't quite work, I could have handled that situation differently.”

In order to successfully navigate the informal induction period and evolve as an ATC at the high school setting, participants sought to create learning networks beyond their institution. The next theme further explains this phenomenon.

Creating Networks for Learning

Participants consistently discussed contacting other ATCs in order to learn how best to deal with their responsibilities. While many ATCs who were new to the high school setting often relied on their previous mentors for advice and direction, it was interesting to find that both novices and veterans at the high school level took the initiative to make connections with other ATCs outside the high school in order to continually learn (Figure, sample concepts A and C, category 2). In fact, Theo stated that while he did not have to travel to away events with the teams, he did so in order to network with the other ATCs at local schools and learn from them:

I have done a lot of traveling with my sports which I don't have to do but because of the bonds I've made with the kids and parents I…go to the away games. [I also] get to talk to the other athletic trainers and [discuss various situations] and sometimes they have some helpful answers or places to look for better answers.

Jeremy also identified networking as critical to learning:

I think that is one of the biggest things you learn as you go is that you do develop some type of network of athletic trainers who you can call and say ‘this is the [most interesting] thing. I've been doing this [procedure] and this [technique], but [the athlete] is just not getting better. What do you think?’

It appears that the role of a high school ATC evolves as he or she gains more experience. Initially ATCs make network connections in order to learn, but as they become more experienced, they play more of a mentoring role, being contacted by less experienced peers for advice about how to deal with issues in the high school setting. For example, Robert stated:

Professionally…my involvement with [the regional professional association] has been really rewarding. It has helped me a lot to deal with life…I will often call up Bruce Johnson (pseudonym) and bounce [ideas] off of him. But [now] more people call me and bounce things off of me more than I call other people. I really feel like I'm the grandfather in the area.

Now, I get phone calls all the time from other athletic trainers about ‘how should I handle this…?’ Maybe it's because I'm old now too, but there is a bigger network now than there was 20 something years ago.

Aside from facilitating learning, networks were also used to provide help and social support (concepts B and D, category 2). For example, Reginald explained that he received a call from a high school ATC in a nearby suburb. The ATC had experienced the death of an athlete approximately 6 months earlier, and called to get contact information for another area ATC who experienced an athlete's death more recently because he wanted to offer his support.

Given the nature of the 2 thematic categories, the resultant proposition is that informal learning procedures are critical to the professional-socialization process for ATCs working in the high school setting. The results of this study suggest that learning through informal means, such as collegial networks, organizational peers, and trial and error, are necessary elements for navigating the high school work setting and being socialized into the ATC role.

DISCUSSION

Professional socialization is a complex process that has the propensity to influence an individual's success in a work environment. The socialization literature6,10,19–22 concludes that the initial entry into an organizational setting is a period of adjustment for many professionals. This study supports these findings, as participants suggested that there was an initial adjustment when entering the high school setting from their previous setting (undergraduate program, master's program, or previous job). Additionally, many participants learned through informal means such as trial and error and by observing others in the organizational setting. Based on a socialization study by Ostroff and Kozlowski,23 this is not unusual, as many individuals frequently rely primarily on observation of others and trial and error to acquire their information in an organization. Thus, informal learning plays a critical role in the professional-socialization process.

Informal Learning

Informal learning can be defined as a lifelong process by which individuals acquire and accumulate knowledge, skills, attitudes, and insights from daily experiences and exposure to an environment and individuals rather than from a structured, hierarchic education system.24 Informal learning generally occurs as a means of achieving particular individual or organizational goals, often as a result of expanded responsibilities.25 Informal learning is reported to account for up to 90% of new learning.26

Informal learning is often intentional but lacks the formalized structure that is found in education-based systems.27 Although some authors27 contended that trial-and-error learning is better defined as incidental learning because it is not intentional, the participants in this study appeared to make intentional, conscious efforts to identify which professional actions or strategies worked and which did not, in order to better meet the demands of their work environments. Informal learning implies that much of the learning was experiential and action based in nature. That is, learning occurred as participants attempted to find solutions to problems or events related to their work setting.

As the participants of this study entered the high school setting and accepted the organizational challenges involved in developing a system of health care, they engaged in informal learning to manage their new responsibilities. Leslie et al25 stated that more informal learning takes place when the goals of an individual and an organization are in alignment. As in this study, a common priority appeared to be shared by ATCs, athletic directors, and coaching staffs that suggested the student-athletes' welfare related to academics and health was a main concern. Perhaps this allowed for a great deal of informal learning to take place.

Garrick28 stated that many respected adult educators link informal learning to concepts such as “autonomous learning,” “self-directed learning,” and “independent learning.” In fact, supporting these claims, Lankard29 suggested that to enhance informal learning, learners must (1) autonomously direct their learning, (2) self-evaluate their learning, (3) engage in critical self-reflection, and (4) think critically. This has many implications for athletic training preservice and continuing education.

Implications for Preservice Athletic Training Education

Athletic training preservice education has thoroughly emphasized the necessity of addressing content, competence, and clinical proficiency. This study, however, identifies the necessity of fostering reflective practitioners who are self-directed and self-evaluative to fully prepare them as informal learners. Educators can enhance these aspects by using reflective journals, individualized learning plans, and formalized student self-evaluations. Although these characteristics may be approached in some programs and curriculums, given their importance to professional development, consideration must be given to making these goals explicit during undergraduate athletic training education.

Implications for Continuing Athletic Training Education

The previously mentioned characteristics have implications relative to continuing professional education as well. For example, Bickham30 suggested that the “foremost goal of continuing professional education is to teach professionals to develop and hone critical-thinking skills.” Continuing professional educators who give ATCs opportunities to conduct verbal reasoning and problem solving and who consciously raise questions can help accomplish this goal.30 Unfortunately, a great deal of continuing education in athletic training focuses on content, such as transferring information by listening to lectures, completing home study courses, or updating cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills, rather than focusing on fostering critical-thinking ability. Moreover, although the transfer of information at a continuing education event can be enlightening for many, a significant issue is whether the information improves professional practice.31

Adult learners will engage in learning activities providing their job performance will be enhanced by the experience.32 Given the participants' need to learn information in order to solve problems linked to practice, continuing education must be more integrated with practice-based problems if it is to be effective.30 Perhaps this is why the participants in this study created learning networks. Ritchie33 commented on networking and stated that “while professionals tend to be self-directing and autonomous, they are not necessarily singular or practicing in isolation. Professionals rely on other professionals to help meet their continuing learning needs.”

Given the self-directed nature of informal learning, perhaps alternative strategies to continuing education, such as self-directed learning plans based on an individual's contextual learning needs are a viable continuing education strategy.34 Such a strategy would foster self-direction, self-evaluation, and self-reflection.33 Additionally, critical self-reflection strategies, such as video analysis of skills and self-evaluations, can promote intentional active learning and the formation of learning communities that facilitate practice-based learning33 and support the direct link of applying continuing professional education to practice.

Limitations

Most of the participants in this study were practicing at schools located in metropolitan areas as designated by the US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, yet none were located in an inner city school or extremely rural setting. The propositions resulting from this grounded theory, therefore, may not be transferable to the inner city or rural school context.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this study was to gain insight into and understanding of how ATCs in the high school setting initially learned and continued to learn their professional responsibilities in an organizational setting. The organizational aspects of the professional-socialization process among high school ATCs are principally informal in nature. As such, the ATCs relied on informal learning strategies during their period of induction. To facilitate their continued development, informal learning networks that largely comprised colleagues outside of the organizational setting were created.

To ensure that individuals effectively learn through informal means, preservice athletic training education programs would be well advised to foster the development of reflective practitioners who think critically and are self-directed and self-evaluative. This can be accomplished by using such educational strategies as reflective journals, learning plans, and independent projects.

Continuing professional educators should also attempt to foster self-evaluation, critical reflection, and critical-thinking ability. Continuing professional educators can accomplish this by employing strategies such as verbal reasoning and problem solving and consciously raising questions and giving clinicians an opportunity to discuss their thought processes in a nonthreatening learning environment. Moreover, it has been argued that continuing education should be linked to practical problems.

Because informal learning is highly contextual, multiple influences have the propensity to shape the extent to which informal learning is successful, including cultural factors, career structure, technology, and learning needs.35 As such, future studies could investigate exactly how these factors influence informal learning and role socialization. Additionally, because informal learning can be inhibited in many ways, it may be helpful to examine the environmental inhibitors (ie, job demands) of informal learning in various athletic training settings.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by a grant from the Mid-America Athletic Trainers' Association.

REFERENCES

- Clark P G. Values in health care professional socialization: implications for geriatric education in interdisciplinary teamwork. Gerontologist. 1997;37:441–451. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvill L M. Anticipatory socialization of medical students. J Med Educ. 1981;56:431–433. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden J. Professional socialization and health education preparation. J Health Educ. 1995;26:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Becker H S, Geer B, Hughes E C, Strauss A L. Boys in White. University of Chicago; Chicago, IL: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Shuval J T, Adler I. The role of models in professional socialization. Soc Sci Med. 1980;14:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glen S, Waddington K. Role transition from staff nurse to clinical nurse specialist: a case study. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7:283–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1998.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H A. The Nurse's Quest for a Professional Identity. Addison-Wesley; Menlo Park, CA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons M. Understanding professional behavior: experiences of occupational therapy students in mental health settings. Am J Occup Ther. 1997;51:686–692. doi: 10.5014/ajot.51.8.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corb D F, Pinkston D, Harden R S, O'Sullivan P, Fecteau L. Changes in students' perceptions of the professional role. Phys Ther. 1987;67:226–233. doi: 10.1093/ptj/67.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teirney W G, Rhodes R A. Faculty Socialization as a Cultural Process: A Mirror of Institutional Commitment. George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development; Washington, DC: 1993. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 93–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pitney W A, Parker J. Qualitative research in athletic training: principles, possibilities, and promises. J Athl Train. 2001;36:185–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S B. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. Jossey Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Sage Publications Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chenitz W C, Swanson J M, editors. From Practice to Grounded Theory: Qualitative Research in Nursing. Addison-Wesley; Menlo Park, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed Sage Publications Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B G, Strauss A L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Côté J, Salmela J H, Baria A, Russell S J. Organizing and interpreting unstructured qualitative data. Sport Psychol. 1997;7:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed Sage Publications Inc; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Colucciello M L. Socialization into nursing: a developmental approach. Nursing Connections. 1990;3:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroot S A, Faucette N, Schwager S. In the beginning: the induction of the physical educator. J Teach Phys Educ. 1993;12:375–385. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson K M. A qualitative study on the socialization of beginning physical education teacher educators. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1993;64:188–201. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1993.10608796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn S P, Hekelman F P. Reality shock: a case study in the socialization of new residents. Fam Med. 1993;25:633–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff C, Kozlowski S WJ. Organizational socialization as a learning process: the role of information acquisition. Personnel Psychol. 1992;45:849–874. [Google Scholar]

- La Belle T J. Formal, nonformal and informal education: a holistic perspective on lifelong learning. Int Rev Educ. 1982;28:159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie B H, Kosmahl-Aring M, Brand B. Informal learning: the new frontier of employee & organizational development. Econ Dev Rev. 1998;15:2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman M C. Environmental inhibitors to informal learning in the workplace: a case study of public school teachers. Adult Educ Q. 2000;50:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Marsick V J, Watkins K E. Informal and incidental learning. New Direct Adult Contin Educ. 2001;89:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Garrick J. Informal learning in corporate workplaces. Hum Resour Dev Q. 1998;9:129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lankard B A. New Ways of Learning in the Workplace. ERIC Clearinghouse for Adult, Career, and Vocational Education; Columbus, OH: 1995. ERIC Digest #161. [Google Scholar]

- Bickham A. The infusion/utilization of critical thinking skills in professional practice. In: Young W H, editor. Continuing Professional Education in Transition: Visions for the Professions and New Strategies for Lifelong Learning. Krieger; Malabar, FL: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cevero R M. Trends and issues in continuing professional education. In: Mott V W, Daley B J, editors. Charting a Course for Continuing Professional Education: Reframing Professional Practice. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles M. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. Gulf Publishing; Houston, TX: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie K. Informal, practice-based learning for professionals: a changing orientation for legitimate continuing professional education? Aust J Adult Commun Educ. 1998;38:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pitney W A. Continuing education in athletic training: an alternative approach based on adult learning theory. J Athl Train. 1998;33:72–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager P. Recognition of informal learning: challenges and issues. J Vocation Educ Train. 1998;50:521–535. [Google Scholar]