Abstract

Appropriate and consistent use of condom remains an effective approach to HIV/AIDS intervention. We analyzed the baseline data gathered for a situationally-based HIV/AIDS intervention in order to assess the potential predictors of condom use among the Uniformed Services Personnel in Nigeria. Using condom purchase as a proxy for intention to use condom, we examined the distribution of the demographic and life style characteristics, knowledge of HIV transmission mode and knowledge of how to correctly use condom. A univariable logistic regression was used to identify the potential predictors, followed by multivariable logistic regression modeling. The knowledge of how to correctly wear condom was the most significant positive predictor of the intention to use condom, adjusted prevalence odds ratio (APOR), 5.99, (95% CI, 1.26, 19.79). The other main positive predictors of intent to use condom were the knowledge of the mode of HIV transmission via blood, APOR 2.43 (95%CI, 1.01, 5.82), saliva (5. 87, 95% CI, 3.15, 10.94), and pre-ejaculatory fluid (APOR, 3.58, 95% CI, 1.67, 7.48). Male gender was also a significant positive predictor of the intent to use condom, APOR, 2.55, (95% CI, 1.10, 5.97). The results further indicated alcohol use (APOR, 0.32, 95%CI, 0.16, 0.61), marijuana use (APOR, 0.24, 95% CI, 0.11, 0.56), and the frequency of oral sexual behavior (APOR, 0.006, 95%CI, 0.002, 0.019) as negative predictors of the intent to use condom. Therefore, these findings suggest that for an HIV/AIDS intervention to be effective in this population, it must incorporate these predictor variables into its design and conduct.

Keywords: Condom use predictors, HIV/AIDS Intervention, Nigerian Uniformed Services Personnel, Condom use intent

INTRODUCTION

HIV infection and AIDS morbidity and mortality prevalence are highest in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). While this region represents only 11% of the total global population, it is home to approximately 70% of the world’s HIV infections and over 25 million people are living with HIV/AIDS in SSA 1. Nigeria is second only to South Africa in the absolute number of people living with HIV, with over 3.6 million people infected with HIV in Nigeria as of the end of the year 2003. Data from sentinel survey in Nigeria indicated an increased in HIV prevalence from 1.8% in 1991 to 5.8% in 2001 2. Regarding Uniformed Services Personnel, HIV prevalence is reported to be higher compared to the general population 3. HIV Work conditions, relatively young age, mobility and values peculiar to the uniformed service personnel have been proposed as being contributory to this high prevalence of HIV in the uniformed services personnel 4. Yet the uniformed services personnel integrate freely with the society and therefore may pose a risk in fueling the pandemic 5.

In a study on knowledge and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among Nigerian navy personnel, 88% of the personnel were reported to have had lifetime multiple sexual partners ranging from 1–40 with a mean of 5.1, while 32% had sexual contact with female sex worker, with 20% within the last six months of the survey 3.

Despite the health and social problems caused by HIV, condom use behaviors are generally not popular. For example, a very low percentage of study population report using condom in the last sexual intercourse: 21.5 % in Tanzania 6, 25 % in Uganda 7,11, and 54.4% in South Africa 8. Even among men having sex with commercial sex workers where perceived vulnerability is expected to be higher, reported usage of condom during the last sexual intercourse was only 46% in Nigeria 9. The proportion of study subjects who had never used condom was also high ranging from 57% in Tanzania 10 to 41% in Uganda 11.

There are a few studies on predictors of condom use among Uniformed Services Personnel. In a study looking at men’s abstinence behavior when their wives are unavailable for sex, lower educational status (primary and secondary), younger age of the wife, and low occupational status and monogamy which may be a proxy for religion was reported to be predictors of condom use 9. Age is also consistently reported as a predictor of condom use behavior in a number of studies done in Africa 9, 10, 12, 13. The role of gender is also an important predictor of condom use. In general, women compared to men were more likely to respond yes to the question: “never use condom”. This is understandable since women are often disempowered in condom use negotiation 28. Condom use was also reported to be less in sexual intercourse among spouses than with casual partners 13.

Though lower educational level was reported to be a good predictor of men’s abstinence in the absence of their wife, higher education predicts condom use 6, 10. Perceived susceptibility to HIV seems to compel people to engage in protective behaviors. Having more sexual partners, having sex with commercial sex workers and knowing someone with HIV positively predicts condom use 6, 11, 13.

Behavioral and epidemiologic factors leading to HIV infection and AIDS morbidity remain to be fully understood. Lifestyle variables, socioeconomic factors and psychosocial propensity are elements that influence HIV preventive behaviors, specifically condom use. We postulated that the intention to use condom may be predicted by socio-demographic factors, knowledge of HIV transmission modes and lifestyle variables. These postulates are based on the accumulative body of evidence that intentions are functions that propagate attitudes and actions and that, given a specific intention, in an action-oriented environment, one’s intention to act leads to an action or anticipated behavior 14–17. To our knowledge, this study represents the first large sample design to examine multiple predictors of condom use among Uniformed Services Personnel in Africa. The significance of this study provides the opportunity to consider these predictors in designing intervention programs for HIV reduction in our study population and the possibility of replicating similar intervention among Uniformed Services Personnel in other parts of Africa and globally.

METHODS

Study Population

Subjects or participants in this study were Nigerian Uniformed Service Personnel. The study population consisted of a cohort of 2214 men and women, age 18 to 50 and older recruited in 2003 for HIV education intervention. Of the 2214, 13.32% were women and 86.63% were men. The detail of the materials and methods is available elsewhere, 18, 19. In brief, our study is based on the baseline data of the intervention that was designed and conducted to reduce HIV risk related behavior in this cohort.

Design

This study utilized the baseline data of the intervention trial in testing the hypotheses that particular socio-demographic characteristics and lifestyle variables predict the intention to use condom. Three cantonments stationed in the Southwest, Nigeria were selected for intervention. Baseline data were collected between June, 2003 and January, 2004. A modified version of a Center for AIDS Intervention Research at the University of Wisconsin, Medical College (Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine) Pridefest Survey was used. This instrument obtains information on socio-demographic, sexual activities, drug use, beliefs about condom, measured on a score of 1–10 scale with 1=100% disagree and 10=100% agree.

Study Variables

Intention to use condom

The outcome variable is the proxy, condom purchase for the intention to use condom. Using a binary response mode, respondents were asked if there is a particular place they go to get condom.

Knowledge of how to correctly wear condom

Good condom use was defined as the correct response on the composite questions defining this covariate (how to correctly wear condom). Respondents were asked to identify correctly the steps in using condom and to place number in sequence beside the steps.

Knowledge of HIV transmission risky behaviors

The knowledge of HIV risk was defined as correct response to the composite defining the most and the least risk for sexual transmission of HIV. Respondents were asked to rank the HIV transmission risky behaviors in order of ‘riskiness” and to assign the largest number to the least risky (4) and the least number to the most risky (1).

Knowledge of HIV modes of transmission

Respondents were given a list of items as modes of HIV transmission and were asked to identify from this list using binary response, with Yes=1 and No=0. The question asked: You can get HIV from……?

Sexual Behavior/Practices

Respondents were asked about the frequency of vaginal sex (penile-vaginal intromission), oral sex (fellatio/cunnilungus) and anal sex (inceptive and receptive rectal) during the past six weeks preceding the survey. The response were categorized as : None=1; 1–5 times=2; 6–10 times=3; 11–15 times=4 and => 16=5 times. In addition, respondents were asked about sex with main partner, sexual preference, sex with HIV positive individual and having sex for money or food. All covariates were binary: Yes=1 and No=2.

Drug and Alcohol Use Behavior

These covariates elicited information on substances as determinants of risky behaviors predicting condom use and HIV transmission. Respondents were asked about the frequency of alcohol and marijuana use during the past six weeks. The responses were categorized to elicit dose-response or biologic gradient: :None or zero times=1; 1–4 times=2 and 5 and above=3.

Beliefs and AIDS

Respondents were asked to indicate how strongly they agree or disagree with the statement: I am worried about catching AIDS so I would be sure to use condom, even in the heat of the moment. The response was measured in a scale of 1 to 10 and interpreted in percentage scale with 1 meaning 100% disagreement and 10 meaning 100% agreement.

Human Subjects and Ethical Consideration

The research protocol was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards (IRB) in the United States and Nigeria.

Statistical analysis

Chi square statistic with Fisher Exact test (correcting for small cells) was used to assess the differences in the baseline characteristics among the gender, ethnicity, education, and age. Using univariable logistic regression analysis, we examined separately the relationship between intention to use condom and the following variables: participants’ age, gender, educational attainment, sexual preference, alcohol and drug use, types of sexual activities, ethnicity, HIV status, casual sex, main sexual partner, sex with HIV positive person, and concerns about contracting AIDS. Next, we performed multivariable analysis using logistic regression to adjust simultaneously for the possible confounding effects of these variables in predicting intention to use condom in preventing HIV infection. We entered into the final model, variables that were statistically and biologically significant and performed the goodness of fit test and regression diagnostic to see if the model fits. We determined a priori that the independent variables in the logistic models would be those significantly associated with appropriate condom use in the univariable analyses, using a statistically significant level of 0.05. We also examined the statistical interaction of age and ethnicity, ethnicity and education, and age and gender. The results of the logistic regression are shown as prevalence odds ratio and adjusted prevalence odds ratio. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical package, version 9.0.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study cohort, with more than two thirds of participants represented by males, 1,918 (86.63%), age group 18–29 years representing more than half of the participants, 1,217 (54.97%), and majority of participants represented by Senior Secondary school (United States equivalent of the 10th to 12th grade) as the highest educational attainment, 1,014 (45.80%). The Hausas comprised the majority in this sample, 564 (25.47%),

Table 1.

Study Characteristics – Socio-demographic information on study participants

| Number (n=2214) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 295 | 13.32 |

| Male | 1,918 | 86.63 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.05 |

| Age (age group in years) | ||

| 18–29 | 1,217 | 54.97 |

| 30–49 | 912 | 41.19 |

| => 50 | 83 | 3.75 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.09 |

| Ethnicity (race or ethnic group) | ||

| Hausa | 564 | 25.47 |

| Ibo | 463 | 20.91 |

| Ijaw | 203 | 9.17 |

| Yoruba | 498 | 22.49 |

| Ibibio | 250 | 11.29 |

| Other | 235 | 10.61 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.05 |

| Education (Highest educational attainment) | ||

| Elementary School | 345 | 15.58 |

| Junior Secondary | 627 | 28.32 |

| Senior Secondary | 1,014 | 45.80 |

| College | 226 | 10.21 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.09 |

Table 2A shows the crude Prevalence Odds Ratio of the potential demographic predictors of intention to use condom in unconditional univariable logistic regression model. Males compared to females were 32% more likely to intend to use condom, prevalence Odds ratio (POR), 1.32, 95% Confidence Interval (CI), 0.85, 2.05, indicating the failure of gender to predict the intention to use condom. Compared to age group (18 – 29), the age group (30 – 49) was 32% more likely to intend to use condom POR, 1.32 (95% CI, 0.94, 1.85). While other ethnic groups compared to Hausa were less likely to intend to use condom, this finding was not significant X (df=5), 5.52, (ρ =0.39). Compared to elementary education, participants with Senior Secondary educational attainment were two times more likely to intend to use condom, POR 2.04, (95% CI, 1.25, 3.34).

Table 2A.

Demographic Predictors of Intention to Use Condom in Univariable Logistic Regression

| Potential Predictors of Intention to use condom | Prevalence Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Chi-square (X) and degree of freedom (df) | Chi Square’s ρ- value ( α < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1.0 Reference(ref) | (ref.) | ||

| Male | 1.32 | 0.85 – 2.05 | 1.58 (1) | 0.28 |

| Age Group (years) | ||||

| 18–29 | 1.0 (ref) | ref | ||

| 30–49 | 1.32 | 0.94, 1.85 | ||

| => 50 | 0.86 | 0.54, 2.47 | 3.08 (2) | Fisher’s Exact |

| 0.19 | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hausa | 1.0 (ref) | ref | ||

| Ibo | 0.70 | 0.43, 1.16 | ||

| Ijaw | 0.56 | 0.31, 1.01 | ||

| Yoruba | 0.69 | 0.42, 1.13 | ||

| Ibibio | 0.60 | 0.34, 1.06 | ||

| Other | 0.85 | 0.45, 1.63 | 5.25 (5) | 0.39 |

| Education | ||||

| Elementary | 1.0 (ref.) | ref | ||

| Jnr. Secondary | 0.79 | 0.50, 1.25 | ||

| Snr. Secondary | 2.04 | 1.25, 3.34 | ||

| College | 0.56 | 0.32, 0.98 | 33.7 (3) | 0.001 |

Table 2B shows the crude prevalence odds ratio of lifestyle variables and sexual preference as potential predictors of intention to use condom. Self-reporting of HIV test and sexual preference were not significant predictors of intention to use condom. Compared to participants reporting sex with female as sexual preference, those reporting sex with males as sexual preference, reflecting majority of females in our study population, were 32% less likely to intend to use condom, POR, 0.68, (95% CI, 0.38, 7.18). Anal sex was marginally a significant predictor of intent to use condom, while vaginal sex with those who reported having sex eleven to fifteen times during the last six weeks compared to those reporting none were ten and half times more likely to use condom, indicating vaginal sex as a significant potential predictor of intention to use condom, POR, 10.67,( 95% CI, 2.75, 41.42). In contrast, oral sex was a significant negative predictor of condom use, thus the more the frequency of oral sex during the last six weeks, the less likely participants were to intend to use condom, X (df=3), 10.33, (ρ=0.016). Compared to participants reporting not having main sexual partner, those with main sexual partner were 33% less likely to intend to use condom, POR, 0.67,(95%CI, 0.48, 0.93). Having sex with main sexual partner was a significant negative predictor of condom use, thus compared with those reporting not having sex with main sexual partner, those having sex with main partner were 59% less likely to intend to use condom, POR, 0.41, (95% CI, 0.29, 0.58). Though not significant, sex with casual partner POR, 1.11 (95% CI, 0.81, 1.53) and sex with HIV positive individual POR, 1.17, (95% CI, 0.28, 4.95) were potential predictors of intent to use condom. The participants reporting having sex for money or food were 36% less likely to intend to use condom, POR, 0.64, (95% CI, 0.22, 1.84).

Table 2B.

Lifestyle Variables Predictors of Intention to Use Condom in Univariable Logistic Regression

| Potential Predictors of Intention to use condom | Prevalence Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Chi-square (X) and degree of freedom (df) | Chi Square’s ρ - value ( α < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV test result (self-reporting) | ||||

| HIV Seropositivity | 1.0 (reference) | Reference | ||

| HIV Seronegativity | 1.65 | 0.38, 7.18 | 0.46 (1) | Fishers exact, 0.36 |

| Sexual preference | ||||

| Sex with female | ||||

| Sex with male | 1.0 (reference) | |||

| 0.68 | 0.44, 1.05 | 3.62 (2) | 0.16 | |

| Alcohol | ||||

| None | 1.0 (reference) | |||

| 1–4 times* | 0.59 | 0.42, 0.83 | ||

| => 5 times | 1.34 | 0.68, 2.60 | 12.95 (2) | 0.002 |

| Marijuana | ||||

| None | 1.0 (reference) | Reference | ||

| 1–4 times | 0.48 | 0.34, 0.69 | ||

| => 5 times | 0.88 | 0.37, 2.01 | 17.42 (2) | 0.001 |

| Main sexual partner | 0.67 | 0.48, 0.93 | ||

| Sex with main partner | 0.41 | 0.29, 0. 58 | ||

| Sex with casual partner | 1.11 | 0.81 1.53 | ||

| Sex with HIV positive | 1.17 | 0.28, 4.95 | ||

| Sex for money or food | 0.64 | 0.22 1.84 | ||

| Anal sex | ||||

| None | 1.0 (reference) | ref | ||

| 1–5 times | 0.99 | 0.20, 0.488 | 12.20(2) | Fisher exact, 0.38 |

| Vaginal sex | ||||

| None | 1.0 (reference) | ref | ||

| 1–5 times | 1.14 | 0.43,2.99 | ||

| 6–10 times | 1.16 | 0.44,3.03 | ||

| 11–15 times | 10.67 | 2.75, 41.42 | 42.9(4) | 0.001 |

| Oral sex | ||||

| None | 1.0 (reference) | ref | ||

| 1–5 times | 0.47 | 0.17, 1.23 | ||

| 6–10 times | 0.10 | 0.02, 0.53 | 10.33(3) | 0.016 |

Alcohol use, marijuana use and sexual behavior during the last six weeks

Participants reporting one to four times of alcohol consumption during the last six weeks were 41% less likely to use condom, POR, 0.59, (95% CI, 0.42, 0.83). Participants reporting one to four times use of marijuana during the last six weeks compared to non-users of marijuana were 52% less likely to intend to use condom, POR, 0.48, (95% CI, 0.34, 0.69). These results demonstrate that the likelihood of intending to use condom decreases with the increase in the frequency of alcohol and marijuana use.

Table 2C represents the knowledge of condom use, HIV transmission risk, and belief regarding AIDS as predictors of intention to use condom in a univariable logistic modeling. Knowledge that HIV is transmitted via vaginal and anal sexual practices were significant negative predictors of intention to use condom. The knowledge of HIV transmission modes (blood, vaginal secretions, semen, saliva and pre-ejaculatory fluid) were significant positive predictors of intention to use condom. Compared to those without adequate knowledge of HIV transmission via blood, those with knowledge transmission via blood were six times (POR 6.9, 95% CI 4.79, 9.98), vaginal secretion were more than five times (POR 5.5, 95%CI, 3.93, 7.72), semen were more than four times (POR, 4,33, 95% CI, 2.95, 6.35), saliva were eight times (POR, 8.06, 95%CI, 5.77, 11.26), and pre-ejaculatory fluids were more than four times (POR, 4.79, 95%CI, 3.45, 6.65) likely to intend to use condom.

Table 2C.

Knowledge of Condom use, knowledge of HIV transmission risk and belief regarding AIDS as Predictors of condom use

| Potential Predictors of Intention to use condom | Prevalence Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Chi-square (X) and degree of freedom (df) | Chi Square’s ρ- value (α < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of good condom use | 3.65 | 1.70, 7.87 | 12.39 (1) | 0.001 |

| Knowledge of HIV risk behaviors | ||||

| Anal Sex | 0.24 | 0.13, 0.42 | ||

| Vaginal sex | 0.27 | 0.18, 0.42 | ||

| Oral sex | 3.76 | 0.51, 27.5 | 1.97 (1) | Fisher’s exact, 0.12 |

| Mutual masturbation | 0.65 | 0.37, 1.13 | 2.36 (1) | 0.12 |

| Knowledge of HIV transmission factors | ||||

| Blood | 6.9 | 4.79, 9.98 | 134.89(1) | 0.001 |

| Vaginal secretions | 5.50 | 3.93, 7.72 | 117.56(1) | 0.001 |

| Semen | 4.33 | 2.95, 6.35 | 64.9(1) | 0.001 |

| Kissing | 8.06 | 5.77, 11.26 | 193.1(1) | 0.001 |

| Ejaculatory fluid | 4.79 | 3.45, 6.65 | 102.8(1) | 0.001 |

| Knowledge of best condom | 0.51 | 0.37, 0.70 | 232.0(1) | 0.001 |

| Worries about having AIDS | 0.35 | 0.24 0.51 | 31.65(1) | 0.001 |

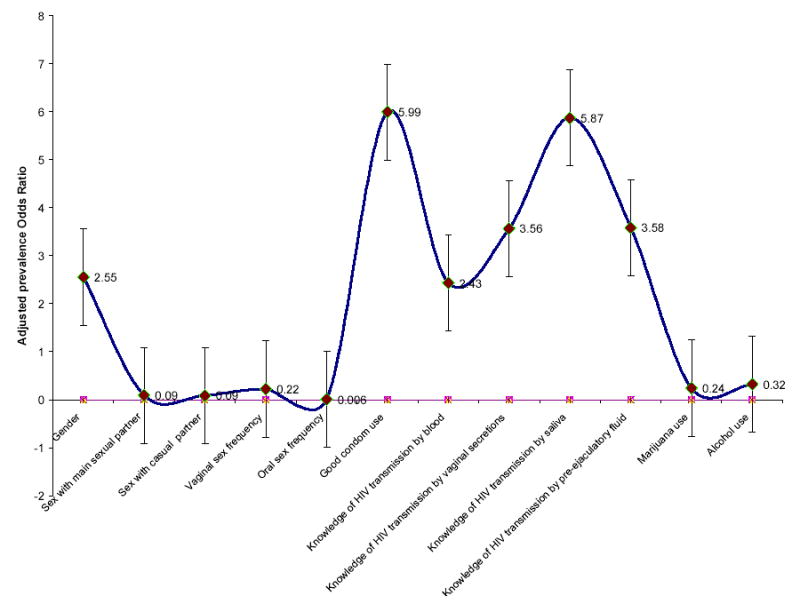

Table 3 presents the predictors of intention to use condom in a multivariable logistic regression model, with adjustment for the confounding effects of the covariates in the model. The predictors in this model after adjustment for the mixing effect remain significant. Gender, knowledge of how to correctly wear condom, knowledge of blood, vaginal secretion, saliva and pre-ejaculatory fluid as the mode of HIV transmission were the positive predictors of the intention to use condom. Therefore, according to these findings, knowledge of how to correctly wear condom was the most significant predictor of the intention to use condom, adjusted prevalence odds ratio (APOR), 5.99, (95% CI, 1.26, 9.79). The other main predictors of intent to use condom were the knowledge of the mode of HIV transmission via saliva, (5. 87, 95% CI, 3.15, 10.94) and pre-ejaculatory fluid (APOR, 3.58, 95% CI, 1.67, 7.48). Male gender was also a potent significant predictor of the intent to use condom, APOR, 2.55, (95% CI, 1.10, 5.97).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis of the predictors of intention to use condom

| Predictors of Intention to use condom | Adjusted Prevalence Odds Ratio (OR)* | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Wald test (z) | ρ-value (α < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 2.55 | 1.10, 5.97 | 2.15 | 0.032 |

| Having sex with main sexual partner | 0.09 | 0.031, 0.260 | −4.45 | 0.000 |

| Having sex with causal partner | 0.09 | 0.031, 0.277 | −4.27 | 0.000 |

| Vaginal sex (1–4 times) | 0.22 | 0.07, 0.65 | −2.73 | 0.006 |

| Oral sex (1–4 times) | 0.006 | 0.002, 0.019 | −8.72 | 0.000 |

| Good condom use | 5.99 | 1.26, 19.79 | 2.29 | 0.022 |

| Knowledge of blood as HIV transmission mode | 2.43 | 1.01, 5.82 | 1.99 | 0.047 |

| Knowledge of vaginal secretion as HIV transmission mode | 3.56 | 1.68, 7.55 | 3.31 | 0.001 |

| Knowledge of kissing as HIV transmission mode | 5.87 | 3.15, 10.94 | 5.58 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge of pre-ejaculatory fluid as HIV transmission mode | 3.58 | 1.67, 7.48 | 3.31 | 0.001 |

| Marihuana use | 0.24 | 0.11, 0.56 | −4.89 | 0.000 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.32 | 0.16, 0.61 | −0.27 | 0.000 |

Twelve significant predictors of intent to use condom after adjustment for age, ethnicity and all the covariates that were significant predictors of the intention to use condom in the univariable logistic regression model.

Figure 1 presents the plot of adjusted prevalence odds versus the positive and negative predictors of the intention to use condom in the multivariable unconditional logistic regression model. The negative predictors of the intent to use condom in this model were having sex with main partner, having sex with casual partner, frequencies of oral and vaginal sex practices, and the frequencies of alcohol and marijuana use. The most potent negative predictor of condom use in our study population was oral sex practice. Thus participants who admitted of having oral sex 1 – 4 times during the last six weeks were 99.4% less likely to intend to use condom, APOR, 0.006, (95% CI, 0.002, 0.019). Having main sexual partner negatively predicted the intent to use condom in this population, APOR, 0.099, (95% CI, 0.031, 0.260). Alcohol was an important negative predictor of the intention to use condom, thus participants who reported of 1 to 4 times alcohol use during the last six weeks were 68 % less likely to intend to use condom, APOR, 0.32, (95%CI, 0.16, 0.61). Participants reporting of marijuana use (1 to 4 times) during the past week were 76% less likely to intend to use condom, APOR, 0.24, (95% CI, 0.11, 0.56).

Figure 1.

Potential Predictors of Intention to use condom in the multivarible logistic Regression Model

DISCUSSION

This study hypothesized that the intention to use condom may be predicted by socio-demographic factors, knowledge of HIV transmission modes, and lifestyle variables. We used the proxy condom purchase for intent to use condom. These hypotheses were based on the accumulative body of evidence that intentions are functions that propagate attitudes and actions, and that given a specific intention, in an action-oriented environment, one’s intent to act leads to an action or anticipated behavior 14–17. Using the baseline data of the intervention, we examined possible predictors of intent to use condom. This study reveals that the Intent to use condom is a complex of behavioral expectations including knowledge of risk, belief, actions, and knowledge of condom use itself, taken collectively and not separately in predicting the probability of condom use intention in this population. Thus by using the multivariable model that allows for the adjustment of the confounding effects of these covariates, our study provides important data in understanding knowledge, risk perception and belief in contracting HIV, as related to intention to use condom in this population.

The univariable logistic modeling predicted the intention to use condom by highest level of educational attainment, alcohol, marihuana, anal and vaginal sexual practice, knowledge of the mode of HIV transmission and appropriate knowledge of condom use. The knowledge of how to correctly wear condom has a predictor of the intention to use condom has been previously reported 20, indicating the consistency of our finding 20. Participants with higher educational attainment were more likely to intend to use condom in the univariable model. However, the effect of education as a predictor of intention to use condom did not persist in the multivariable model. This observation points to the complexities of variables that predict condom use. The intention to use condom may be influenced by financial decision besides psychosocial determinants. Like most previous studies9, 10, 12, 13, age was a predictor of intent to use condom in our study, but this influence (predictability) disappeared after adjustment for other variables in the multivariable analysis. It is likely that age interacts with gender and socio-economic status and socioeconomic status interacts with education in predicting the intention to use condom. These interactions were removed from the final model due to lack of significance at αlevel, 0.05 (ρ <0.05).

Univariable and multivariable analysis regarding gender as a predictor of intent to use condom, in this study is consistent with previously published findings, 13, 21. Compared to men, women were of disadvantage in intent to use condom. This has been explained on the premise of inability to negotiate condom use associated with socio-economic motivation of sexual encounter and lack of empowerment among this gender 28. Our finding is suggestive of the need to evaluate gender and other socio-economically affiliated factors in an intervention aimed at condom use in reducing HIV infectivity.

Having a main sexual partner was a negative predictor of the intent to use condom in both models. This finding is coherent and consistent with other similar findings, 13. In retrospect, having information on marital status and current cohabitation variable might have provided useful information on the interpretation of this covariate. However despite this inadequacy, maintaining one sexual partner, implying monogamous relation negatively predicted the intent to use condom 22, 23

Alcohol and Marihuana use as negative predictors of intent to use condom has been illustrated in previous studies in sampled populations 24. Albeit the non dose-response or biologic gradient association, our result is consistent some recent finding24 The knowledge of HIV modes of transmission was a potent predictor of condom use in the univariable model and persisted after adjustment for biologically and statistically significant variables in the final multivariable model. Our findings thus agree with earlier finding on knowledge of HIV transmission risk factors and the intention to use condom 24. Substance use (alcohol and marijuana) in this study represents very potent predictor of the intent to use condom. Therefore the likelihood of not intending to use condom increases with exposure to alcohol and marijuana use in this sample.

Unlike previous studies reporting significant racial variation in condom use when comparing blacks and whites in the United States 27, our result revealed the contrary in the ethnic groups identified in this population. In the univariable model, compared to Hausas, other ethnic groups were less likely to intend to use condom. But because of the biologic significance of ethnicity, we allowed this covariate in the final model and found insignificant predictability across all ethnic strata. Based on the mainstream theory that the Hausas are more religious and hence would be more likely to intend to use condom, this study is yet to confirm this postulate in this sample.

Unique in this study is the predictability of knowledge of how to correctly wear condom, measured by the appropriate steps in condom use prior to sexual act. In both the univariable and multivariable models, this association persisted with a reasonable strength of the measure or predictability. Studies have demonstrated that the appropriate and consistent use of condom provide as much as 94% reduction in the risk of HIV transmission 25, and that if properly used, condoms are effective in retarding the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections 26.

While some studies have shown that concerns about HIV or AIDS increase one’s intention to use condom 7, our study failed to demonstrate this correlation. In addition, we failed to demonstrate the intent to use condom with sexual activities with HIV positive individuals in this sample. In the former, it appears that the scale used to measure the covariate “worried about getting AIDS”, disagreed and agreed on a scale of 1–10 did not measure this response adequately and hence the possibilities of misclassification. With the latter, this finding though significant, remains to be explained in our sample. A plausible explanation may be attributed to the belief in the underdeveloped nations that AIDS is the industrialized or developed nation’s machinery to inhibit and deter human sexual response and sexual expression. Furthermore, despite the perception of high risk for HIV and AIDS among blacks, this population is likely to response with anger to condom use 27.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this design represents the first large Uniformed Services Personnel study to identify the predictors of the intention to use condom in this population. Knowledge of how to correctly wear condom, gender, education (not a predictor in the multivariable modeling), knowledge of HIV transmission modes, alcohol and marijuana use, oral sexual practice, casual sexual practice and having main sexual partner are potential predictors of intent to use condom in this sample. While this population is representative of Uniformed Services Personnel in the Sub-Saharan region of the world, it does not represent the nonuniformed population in this region, but may reflect similar special population worldwide. Therefore, HIV intervention aimed at increasing condom use should consider these covariates, including age and ethnicity in its design and conduct. This study is limited by its very design; cross sectional, sampling issues and socially acceptable or desirable response. Regarding sampling issues, we were not able to use design logistic regression model, which is most adequate in analyzing survey data. However, given the examination of the distribution of the data prior to modeling, it is unlikely that sampling weight bias might have significantly biased these findings. While self-reporting on sexual issues are more prone to bias, the methodology utilized in this study seems to have reduced some of the inherent bias in sexually related survey research. Another limitation is the absence of data on socio-economic variables such as income level since intention to use condom may correlate with means to purchase condom. In conclusion, our study is suggestive, despite these limitations, of the utilization of these predictor variables in designing HIV intervention aimed at condom use for Uniformed Services Personnel in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant #01-038-258, from the World AIDS Foundation, Paris, France. Preparation of this manuscript was facilitated in part by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant #RO1 MH073361-02. Dr. Harrison N. Kamiru is a research scholar at Baylor International Pediatrics AIDS Initiative supported by grant D43 TWO1036 from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health. The authors are grateful to Jennifer Krueger (Galveston College) and Jonathan Brunt (University of Houston) for assisting in proofreading the manuscript and providing technical supports in the preparation of the tables and figure.

Footnotes

Guarantor: Dr. Ekere James Essien

References

- 1.UNAIDS 2004 report on global AIDS pandemic: 4th Global report.

- 2.Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria Sentinel Survey Report, 2003: National HIV Sero-prevalence Sentinel Survey Technical Report.

- 3.Nwokoji UA, Ajuwon AJ. Knowledge of AIDS and HIV risk-related sexual behavior among Nigerian naval personnel. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:24–24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS: AIDS and the Military: UNAIDS point of View. Geneva, Switzerland, Joint United nations Program on HIV/AIDS, 1998.

- 5.UNAIDS, 2002 report on global AIDS pandemic: 2nd Global report.

- 6.Lugoe WL, Klepp KI, Skutle A. Sexual debut and predictors of condom use among secondary school students in Arusha, Tanzania. AIDS Care. 1996;8:443–452. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adih WK, Alexander CS. Determinants of condom use to prevent among youth in Ghana. J adolesc Health. 1999;24:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peltzer K. Factors affecting behaviors that address HIV risk among senior secondary school pupils in South Africa. Psychol Rep. 2001;89:51–56. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.89.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawoyin TO. Condom use with sex workers and abstinence behaviour among men in Nigeria. J R Soc Health. 2004;124:230–233. doi: 10.1177/146642400412400521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapiga SH, Lwihula GK, Shao JF, Hunter DJ. Predictors of AIDS knowledge, condom use and high-risk sexual behaviour among women in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. Int J STD AIDS. 1995;6:175–183. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuwaha F, Faxelid E, Höjer B. Predictors of condom use among patients with sexually transmitted diseases in Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:491–495. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199910000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelzer K, Promtussananon S. HIV/AIDS knowledge and sexual behavior among junior secondary school students in South Africa. Journal of social sciences. 2005;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mbizvo MT, Ray S, Bassett M, McFarland W, Machekano R, Katzenstein D. Condom use and the risk of HIV infection: Who is being protected? Cent Afr J Med. 1994;40:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Champion V, Skinner CS, Menon U. Development of a self-efficacy scale for mammography. Res Nur Heal. 2005;28:329–336. doi: 10.1002/nur.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longshore D, Stein JA, Conner BT. Psychosocial antecedents of injection risk reduction: a multivariate analysis. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:353–66. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.353.40395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thrasher JF, Campbell MK, Oates V. Behavior-specific social support for healthy behaviors among African American church members: applying optimal matching theory. Health Educ Behav. 2004;2:193–205. doi: 10.1177/1090198103259184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72:271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Essien J, Meshack A, Ekong E, Williams M, Amos C, James T, Peters R, Ogungbade G, Ross M. Effectiveness of a situationally-based HIV risk-reduction intervention for the Nigerian Uniformed Services on readiness to adopt condom use with casual partners. Counselling, Psychotherapy, and Health. 2005;1:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross MW, Essien EJ, Ekong E, James TM, Amos CE, Ogungbade GO, Williams ML: The impact of a situationally-focused individual HIV/STD risk reduction intervention on risk behavior in a one year cohort of Nigerian military personnel. Military Medicine (In Press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Reitman D, Lawrence JS, St, Jefferson KW, et al. Predictors of African American adolescent’s condom use and HIV risk behavior. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:499–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laraque D, McLean DE, Brown-Peterside P, et al. Predictors of reported condom use in central Harlem youth as conceptualized by the health belief model. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norman LR. Predictors of consistent condom use: a hierarchical analysis of adults from Kenya, Tanzania and Trinidad. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:584–590. doi: 10.1258/095646203322301022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Leary A, Goodhart F, Jemmott LS, et al. Predictors of safer sex on the college campus: a social cognitive theory analysis. J Am Coll Health. 1992;40:254–256. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.9936290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Determinants of condom use stage of change among heterosexually-identified methamphetamine users. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8:391–400. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes KK, Levine R, Weaver M. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:454–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner R, Blackburn RD, Upadhyay UD: Closing the condom gap. Baltimore: John Hopkins University School of Public health, Population Information Program. Population Reports Series H. No. 9.

- 27.Johnson EH, Jackson LA, Hinkle Y, et al. What is the significance of black-white differences in risky sexual behavior? J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86:745–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soet JE, Dilori C, Dudley WN. Women’s self-reported condom use: intra and interpersonal factors. Women and Health. 1998;27:19–32. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]