Abstract

Purpose: This project enhanced access to and awareness of health information resources on the part of public libraries in western Pennsylvania.

Setting/Participants/Resources: The Health Sciences Library System (HSLS), University of Pittsburgh, conducted a needs assessment and offered a series of workshops to 298 public librarians.

Brief Description: The National Library of Medicine–funded project “Access to Electronic Health Information” at the HSLS, University of Pittsburgh, provided Internet health information training to public libraries and librarians in sixteen counties in western Pennsylvania. Through this project, this academic medical center library identified the challenges for public librarians in providing health-related reference service, developed a training program to address those challenges, and evaluated the impact of this training on public librarians' ability to provide health information.

Results/Outcome: The HSLS experience indicates academic medical center libraries can have a positive impact on their communities by providing health information instruction to public librarians. The success of this project—demonstrated by the number of participants, positive course evaluations, increased comfort level with health-related reference questions, and increased use of MEDLINEplus and other quality information resources—has been a catalyst for continuation of this programming, not only for public librarians but also for the public in general.

Evaluation Method: A training needs assessment, course evaluation, and impact training survey were used in developing the curriculum and evaluating the impact of this training on public librarians' professional activities.

INTRODUCTION

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, many public libraries housed professional medical collections as part of their goal of “stimulating all neighborhood intellectual and scientific progress” [1]. With the advent of credentialing standards for medical schools and hospitals and the need for specially trained medical librarians, the public library's role in housing professional collections diminished. Instead, most refocused their energies on collecting medical publications appropriate for use of the lay public [2].

This divergence of goals and populations served between public libraries and the academic medical center libraries continues to challenge both types of libraries. As the health care system increasingly involves patients and families in treatment decisions, the public's appetite for health information in print [3], and particularly on the Internet [4], is growing exponentially. Public libraries have reported that health information questions account for 6% to 20% of reference requests [5]. A short survey conducted from May 18, 2000, through June 6, 2000, at the Science and Technology Division reference desk at the main branch of the Carnegie Public Library in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, found that 17.4% of all questions asked were health related [6].

Some academic medical center libraries also offer services to the public, but each must maintain a balance between meeting the needs of the public and fulfilling their obligation to serve their primary clientele [7]. Many different models of the two types of libraries working together have been tried over the years. Public libraries and academic medical center libraries have collaborated on health information networks [8], outreach services to rural citizens [9], Web-based information services [10], multi-institutional reference services [11], continuing education through a talkback telephone teleconference [12], and a variety of other consumer health information partnerships [13]. The academic medical center library's role can be one of facilitator and partner, assisting public libraries with health information education and training programs for their staff.

THE “ACCESS TO ELECTRONIC HEALTH INFORMATION FOR THE PUBLIC” PROJECT

In February 2000, the Health Sciences Library System (HSLS) of the University of Pittsburgh was awarded funding by the National Library of Medicine as one of forty-nine projects in thirty-four states designed to improve access to electronic health information for the public. HSLS's primary goals for this project were to:

enhance access to health information and awareness of health information resources for consumers in western Pennsylvania

increase health information literacy by teaching how to search the Internet for reliable and authoritative resources

demonstrate the role of the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINEplus‡ and PubMed§ in locating health information

The primary clientele of HSLS are the faculty, staff, and students of the six schools of the health sciences at the university, as well as the physicians, residents, and staff of the nineteen hospitals of the UPMC/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Though the public is not restricted from entering the library and using the print resources, onsite use by those unaffiliated with the university or the health system is not encouraged.

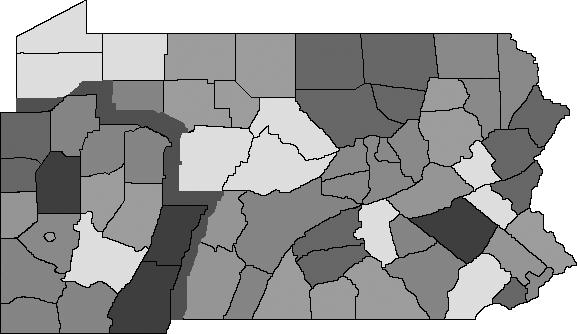

To achieve the project's goals, the HSLS approach was to provide support and training on health information services and resources to public librarians in western Pennsylvania. HSLS partnered with the Allegheny County (Pennsylvania) Library Association (ACLA), a federated library system with forty-four participating libraries in and around Pittsburgh. ACLA also served as liaison to public libraries located in the surrounding sixteen counties (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sixteen counties participating in public librarian training

With the assistance of ACLA, an advisory group composed of eighteen public librarians representing 146 public libraries and library systems in western Pennsylvania was formed. The role of this advisory group was to assist in developing a needs assessment to determine the curriculum content and the preferred method of delivery and schedule for training. In addition, they would help market this training initiative to public librarians.

NEEDS ASSESSMENT

In March 2000, a needs assessment survey (Appendix A) was sent to public libraries in the target area. The purpose of the needs assessment was to identify the health information training needs of public librarians. The needs assessment asked about the types of health questions public librarians received from their users, the sources used to answer these questions, the librarians' use of the Internet, and the librarians' concerns in providing health information. Public libraries in Pennsylvania are arranged into districts with the larger public library in the district designated as the district center library. ACLA distributed the needs assessment survey to each of the district center libraries. In turn, the district center libraries sent the survey to the public libraries in their regions.

A total of forty-four surveys were returned. Many were completed by more than one librarian at a particular library or represented information compiled by an entire library system or district center. Many surveys had multiple responses for each question. When analyzing the responses, it was impossible to delineate the number of librarians or number of respondents for each question. Therefore, the data analyzed below might represent group answers to some questions.

Analysis of the responses revealed that public librarians handled a wide variety of health questions. The most common type of questions focused on specific diseases, with respondents naming lupus, cancer, reproductive disorders, osteoarthritis, diabetes, genetic disorders, and Down syndrome as examples. The second highest category of health questions related to drugs or medications. Examples are: “What are the side effects of lipitor?”; “What are the latest therapies for multiple sclerosis?”; and “I'm not feeling well. Could my symptoms come from the drugs I'm taking?” The third largest type of health questions received by public librarians was about alternative therapies and modalities, such as “What is reiki and when should it be used?” or “I don't want to take hormones. What are the herbal remedies for menopause?” Questions on specific phytotherapies and vitamins were common. Finally, many health questions fell into the category of wellness and prevention, focusing on topics such as weight loss and diets, as well as nutrition and disease prevention.

Survey results further revealed that public librarians had concerns about their print health collections. They were unsure about what a basic health collection for a public library should contain and what reference books should be used to answer specific disease questions. They acknowledged that their print collections were out-of-date and reported that they were often unable to find answers to health questions with print resources on hand. When asked, “Do you feel that you have resource limitations in answering medical questions,” the overwhelming majority (84%) responded “yes.”

Public librarians also indicated that using the Internet to answer health-related questions was a challenge. Many librarians using search engines to locate health information had concerns about the quality of the retrieved information. Only 12% of the responses indicated use of the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINEplus, and 27% had used PubMed. The complexity of medical databases also caused problems. Public libraries in Pennsylvania have access to resources such as Clinical Reference Systems (patient-education materials), MICROMEDEX USP DI (drug information), and the Health Reference Center (full-text consumer health information) through the Pennsylvania Online World of Electronic Resources (POWER). Survey results revealed that librarians had little understanding of the content of these freely available databases.

Responses also indicated concern about how to provide consumer health reference. Difficulty with medical terminology was mentioned by most as their primary difficulty. One response stated that requestors “never have the correct spelling, so we [librarians] spell the medical term or drug phonetically. We look for information on how the drug name sounds or the procedure is pronounced like [sic] and then determine which medical term is the correct one.” Another respondent reported that “a patron asked for ‘bubble abration’—I tracked it down as balloon endometrial ablation!” Many reported that questioners had limited information, and comments such as “the doctor didn't explain it well” or “I didn't understand what my health provider said” were common.

Other responses indicated that, though many public librarians felt unqualified or lacked confidence in dealing with health questions, they also felt pressed to assist individuals in interpreting and understanding information without giving the impression of offering medical advice. Responses also indicated librarians were sometimes uncomfortable in dealing with individuals under stress from coping with a difficult diagnosis or having to make a crucial health decision.

Finally, 61% of responses by public librarians reported that they had limited time available to answer medical questions. Many individuals required extensive assistance from a librarian in using the Internet to locate answers to their specific questions. Indeed, a study in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, recently found that the public library was an important point of access to the Internet for individuals with low incomes and low educational levels and for those over the age of sixty-five [14].

WEBSITE

Based on the results of the needs assessment, project activities focused on development of a training curriculum and a specialized Website for consumer health information. The training would highlight how to approach and analyze health-related reference questions, how to locate quality health information in print and on the Internet, and how to use MEDLINEplus and other quality Internet sites to begin searching for information.

The HSLS Health Information for the Consumer site** (Figure 2) was introduced in July 2000. This site was developed both as a training site and as the home site for a patient and family library managed by HSLS at a UPMC/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center hospital. The Website provides an instructional approach to locating consumer health information. Each topical area offers four to five links to high-quality Web resources, with the first link usually to a MEDLINEplus resource. Each page then has a didactic section with instruction on the reasons the sites were selected, information tips, and additional links and references. This site provides a resource directory of health and social service agencies in southwestern Pennsylvania, as well as tools to locate or find a physician.

Figure 2.

Health Information for the Consumer site

TRAINING

A series of three workshops was developed with the series titled “Health Information for Public Librarians: Understanding Medical Information and Identifying Resources for the Southwestern Pennsylvania Community.” Each four-hour workshop was approved for four Medical Library Association continuing-education units and structured to be part of MLA's Consumer Health Information Specialization program.

“Workshop I: Introduction to Medical Information” was a didactic program offered only once to a large group of participants and served as the “theory class.” Various instructors discussed the consumer health reference interview, the concept of evidence-based information, and collection development. A clinical social worker discussed methods of dealing with individuals under stress, and a cancer patient educator reviewed the types of health information available to patients from a health system.

“Workshop II: Internet Resources and Databases” was designed as a hands-on experience in a computer lab, with a maximum of twelve students and two librarian instructors. This class format was more informal and offered the librarians an opportunity to express their particular experiences or concerns. The primary focus was on using HSLS's Health Information for the Consumer Website, NLM's MEDLINEplus, and PubMed, as well as other National Institutes of Health consumer sites such as ClinicalTrials.gov and the National Cancer Institute's cancer.gov. An overview of the medical databases on POWER was also included.

Participants learned about the different resources by using a health information case study. This case study follows a fictitious library patron's increasingly complex quest for health information [15]. The patron begins by asking for basic information about his diagnosis and drug side effects. He proceeds to more complicated requests for evidence-based information, as he tries to decide among various treatment options.

“Workshop III: Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Information Resources” addressed consumer interest in CAM, locations of scientific-based CAM studies, information about the primary herbal monographs, role of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the National Institutes of Health, and issues surrounding quackery and fraud.

From November 2000 through July 2001, 298 attendees participated in the workshops. Workshop I, offered only once, had seventy-nine participants. Workshop II was offered at seven locations in the sixteen-county area with 112 librarians participating. Another sixty-seven librarians attended a two-hour demonstration version of this program that was offered three times at varied locations. Workshop III was offered three times to forty participants.

Class evaluations were returned by 222 participants. The combined ratings, taken from the class evaluations of all three workshops, indicated the following: 92% of participants from all three workshops agreed with the statement “I acquired knowledge and skills I can use.” Overall, 75% rated the courses as “excellent” and another 23% as “above average.” Ninety-nine percent of participants rated the instructors as “knowledgeable,” and 92% agreed that they were effective teachers.

TRAINING IMPACT SURVEY

To determine the long-term impact of training on the public librarians' professional activities related to locating health information, a training impact survey (Appendix B) was sent to the 112 participants of “Workshop II: Internet Resources and Databases.” Participants from Workshop II were selected to receive the survey because this workshop provided the most comprehensive hands-on experience. The survey was sent three months after completion of training.

The response rate was 41%; forty-seven surveys were returned. When asked, “After completing the workshop, how comfortable do you feel assisting patrons with medical questions?,” 93% of respondents felt “comfortable” assisting the public with their medical questions, with 7% “somewhat comfortable.”

After the training, librarians consulted multiple resources to answer health questions. Ninety-four percent consulted MEDLINEplus, with 85% using it at least monthly. About half of the public librarians (49%) used PubMed to answer their health questions. PubMed was used weekly by 21% and at least monthly by 41%. Three months after training, 89% of public librarians continued to use the HSLS Health Information for the Consumer site. This site was used weekly by 44%, another 33% monthly, and 23% once every couple of months. Eighty-one percent of librarians used medical reference books, 68% used circulating books, and 59% used POWER.

ONGOING ACTIVITIES

HSLS continues its partnership with the Allegheny County Library Association to update public librarians about health information issues. In April 2002, the workshop “Are You Ready? Bioterrorism Resources for the Librarian” was offered to this population. In fall 2002, HSLS librarians offered additional workshops for this group.

Public librarians participating in the first series of workshops requested that HSLS offer training directly to their communities. HSLS faculty librarians have developed a two-hour hands-on class for the public focusing on MEDLINEplus.

HSLS librarians have also served as faculty for non-credit courses offered to the public through the University of Pittsburgh Center for Lifetime Learning. Workshops were offered for the first time in winter 2002 and are continuing.

The HSLS Health Information for the Consumer site will be upgraded to reflect new initiatives and additional consumer health information. This site is a link from the University of Pittsburgh Office of Human Resources, providing easy access to health information for the university's community.

DISCUSSION

Providing hands-on intensive instruction in varied locations to a large number of participants from diverse settings offered many challenges. Workshops were initially offered at the Falk Library of the Health Sciences on the main campus of the University of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh. Participants at these early workshops were primarily from public libraries within the city limits. Librarians from outside Allegheny County were often reluctant to travel to the city. Many found it difficult to be away from the library for a full day, because small libraries often rely on only one or two librarians for coverage. Workshop instructors were able to schedule training sessions in computer labs in outlying areas, including two district library centers and the University of Pittsburgh regional campuses at Greensburg, Johnstown, and Titusville, Pennsylvania. Relocating the training nearer to the public librarians contributed to the success of this program.

The HSLS experience demonstrates that academic medical center libraries can have a positive impact on their communities by providing health information instruction to public librarians. The success of this project—indicated by the number of participants, positive course evaluations, increased comfort level with health-related reference questions, and increased use of MEDLINEplus and other quality information resources—has been a catalyst for continuation of this programming, not only for public librarians but also for the public in general.

CONCLUSION

Opportunities exist for consumer and patient health information training through partnerships between academic medical center libraries and public libraries. These programs could benefit health sciences librarians with little public library experience as well as public librarians with little health information or patient-education experience. Traineeships or internships would allow for focused education on consumer health and patient-education issues and assist public librarians in their roles as providers of consumer health information and patient education [16].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Reed Williams, 1999–2000 trainee, Health Sciences Library and Bioinformatics, Health Sciences Library System, and the Center for Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh, for her development and compilation of the needs assessment. We recognize Marilyn Jenkins, executive director of the Allegheny County Library Association, for her continuing support of these programs.

APPENDIX A

Access to electronic consumer health information for the public.

Needs assessment survey, Health Sciences Library System, University of Pittsburgh.

Thank you for participating in this survey. We hope to gather information that will help us help you provide better library services to your customers or patrons searching for health and medical information. Your input is greatly appreciated.

1. Please indicate below the general kinds of health or medical information most frequently sought by customers or patrons at your library: Please check all that apply.

□ Drugs/Medications

□ Specific disease or illness

□ Health/wellness/prevention

□ Health care systems or delivery

□ Health care providers

□ Alternative medicine

Of those above, please rank the three most frequent (e.g., 1. Drugs, 2. Health care providers, 3. Specific disease) _______________________________________________________________________________

2. If you could estimate a percentage of health or medical questions asked primarily for student papers, homework, or reports, what would it be? _______________________________________________________________________________

3. If you could estimate a percentage of health or medical questions asked over the phone (as opposed to in person), what would it be? _______________________________________________________________________________

4. Which of the following sources do you consult to answer medical reference questions? Please check all that apply.

□ Reference books

□ Circulating books

□ Colleagues at your own library

□ Websites

□ Colleagues at other libraries

□ Journal articles (full text via databases or in print)

□ Other source. Please specify: _______________________________________________________________________________

Electronic databases

□ Health Source Plus, USP DI, or Clinical Reference Systems via EbscoHost

□ Health Reference Center via Infotrac

□ Alt-Health Watch

□ MEDLINE

□ Other electronic database. Please specify: _______________________________________________________________________________

Of those above, please indicate the three types of sources you use most frequently (e.g., 1. reference books, 2. Websites, 3. health reference center) _______________________________________________________________________________

5. Have you used MEDLINE in the past year?

□ Yes

□ No

If yes, what mode of access have you used?

□ PubMed

□ Internet Grateful Med

□ Fee-based system. Please specify: _______________________________________________________________________________

If you have used MEDLINE, do you feel comfortable using it?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Somewhat

6. Have you ever used the PubMed Web interface from the National Library of Medicine (NLM)?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Don't know

7. Have you ever used MEDLINEplus from the NLM?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Don't know

8. On a scale of 1 to 5, how would you rate your comfort level with medical terminology? (1 = extremely uncomfortable and 5 = perfectly comfortable) _______________________________________________________________________________

Is medical terminology a topic you feel you need more information about?

□ Yes

□ No

9. If you had to divide up 100% of your health or medical questions, about what percentage fall into the following categories:

______Quick/ready reference (0–3 minutes)

______Reference answered at time of call or question at desk (4–10 minutes)

______Follow-up (e.g., call back, consult colleague, more in-depth research)

100% total

10. Training on what kinds of topics would be most helpful to you in your work? _______________________________________________________________________________

11. What are the major health or medical topics most frequently sought by customers or patrons at your library? Please be as specific as possible. _______________________________________________________________________________

12. What, if anything, do you find difficult about answering medical reference questions? _______________________________________________________________________________

Do you feel that you have time limitations in answering medical questions?

□ Yes

□ No

Do you feel that you have resource limitations?

□ Yes

□ No

13. Do you refer your patrons or customers to other libraries to answer health or medical questions?

□ Yes

□ No

If yes, to which library(ies) do you most often refer? _______________________________________________________________________________

14. To help us better understand your role in serving patrons or customers, please indicate your job title:

□ Library assistant

□ Librarian

□ Administrator/librarian. Please provide job title: _______________________________________________________________________________

□ Administrator/non-librarian. Please provide job title: _______________________________________________________________________________

□ Other. Please specify: _______________________________________________________________________________

15. Please use the space below (or attach an extra sheet) to provide at least two medical or health reference questions you or your staff members have received in the past six months. Particularly difficult questions would be helpful. _______________________________________________________________________________

APPENDIX B

Health information for public librarians training impact survey.

1. After completing the workshops, how comfortable do you feel assisting patrons with medical questions. Please circle one below.

Very comfortable

Comfortable

Somewhat comfortable

Uncomfortable

Very uncomfortable

2. Which of the following sources do you currently consult to answer medical reference questions? Please check all that apply.

□ Reference books

□ MEDLINEplus

□ USP DI

□ Circulating books

□ HSLS CHI Web page

□ Clinical Reference System

□ Colleagues

□ PubMed (MEDLINE)

□ Alt-Health Watch

□ Health Source Plus

□ Health Reference Center

3. Do you use MEDLINEplus from the National Library of Medicine (NLM)?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Don't Know

Where did you learn about it? _______________________________________________________________________________

4. If yes, how often do you use it?

□ Several times a day

□ Once daily

□ 2–3 times per week

□ One time a week

□ Several times a month

□ Once a month

□ Once every couple of months

□ Never

5. Do you ever use MEDLINE via NLM's PubMed Web interface?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Don't know

Where did you learn about it? _______________________________________________________________________________

6. If yes, how often do you use it?

□ Several times a day

□ Once daily

□ 2–3 times per week

□ One time a week

□ Several times a month

□ Once a month

□ Once every couple of months

□ Never

7. Do you ever use HSLS's Health Information for the Consumer Website?

□ Yes

□ No

□ Don't know

Where did you learn about it? _______________________________________________________________________________

8. If yes, how often do you use it?

□ Several times a day

□ Once daily

□ 2–3 times per week

□ One time a week

□ Several times a month

□ Once a month

□ Once every couple of months

□ Never

Footnotes

* Funded in part by the National Library of Medicine under a contract (#NO1-LM-6-3521) with the New York Academy of Medicine.

† Based on a presentation at the Donald A. B. Lindberg Lecture and Symposium, Center for Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; June 28, 2002.

‡ The MEDLINEplus Website may be viewed at http://medlineplus.gov.

§ The PubMed Website may be viewed at http://pubmed.gov.

** The Health Sciences Library System (HSLS) Health Information for the Consumer Website may be viewed at http://www.hsls.pitt.edu/chi/.

Contributor Information

Charles B. Wessel, Email: cbw@pitt.edu.

Jody A. Wozar, Email: jwozar@pitt.edu.

Barbara A. Epstein, Email: bepstein@pitt.edu.

REFERENCES

- Wannarka M. Medical collections in public libraries of the United States: a brief historical study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1968 Jan; 56(1):1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannarka M. Medical collections in public libraries of the United States: a brief historical study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1968 Jan; 56(1):10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering MJ, Harris J. Consumer health information demand and delivery: implications for libraries. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1996 Apr; 84(2):209–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. Vital decisions: how Internet users decide what information to trust when they or their loved ones are sick. [Web Document]. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trust, 2002. [22 May 2002; cited 27 Aug 2002]. <http://www.pewinternet.org/reports/pdfs/PIP_Vital_Decisions_May2002.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Wood FB, Lyon B, Schell MB, Kitendaugh P, Cid VH, and Siegel ER. Public library consumer health information pilot project: results of a National Library of Medicine evaluation. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):314–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- \[nmConsumer health information in Allegheny County: an environmental scan/conducted by the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Pittsburgh for the Jewish Healthcare Foundation. Pittsburgh, PA: Jewish Healthcare Foundation, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander SM. Providing health information to the general public: a survey of current practices in academic health sciences libraries. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Jan; 88(1):62–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild EY, Furman JA, Addison BL, and Umbarger HN. The CHIPS project: a health information network to serve the consumer. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Oct; 66(4):432–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guard R, Fredericka TM, Kroll S, Marine S, Roddy C, Steiner T, and Wentz S. Health care, information needs, and outreach: reaching Ohio's rural citizens. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):374–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KH. Health Infonet of Jefferson County: collaboration in consumer health information service. Med Ref Serv Q. 2001 Fall; 20(3):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander S. Consumer health information partnerships: the health science library and multiple library system. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1996 Apr; 84(2):247–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wender RW. Talkback telephone network: techniques of providing library continuing education. Spec Libr. 1983 Jul; 74(3):265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LM, Manbeck V. CHI collections in public libraries: a historical perspective. In: Baker LM, Manbeck V, eds. Consumer health information for public librarians. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2002:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Consumer health information in Allegheny County,. op. cit., 24. [Google Scholar]

- Health Sciences Library System, University of Pittsburgh. Practice case (Mr. Harris). [Web Document]. Pittsburgh, PA: The University. [rev. Jan 2001; cited 27 Aug 2002]. <http://www.hsls.pitt.edu/chi/case.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Medical Library Association and the Consumer and Patient Health Information Section (CAPHIS/MLA). The librarian's role in the provision of consumer health information and patient education [policy statement]. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1996 Apr; 84(2):238–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]