Abstract

Objective: To present Situational Leadership as a model that can be implemented by clinical instructors during clinical education. Effective leadership occurs when the leadership style is matched with the observed followers' characteristics. Effective leaders anticipate and assess change and adapt quickly and grow with the change, all while leading followers to do the same. As athletic training students' levels of readiness change, clinical instructors also need to transform their leadership styles and strategies to match the students' ever-changing observed needs in different situations.

Data Sources: CINAHL (1982–2002), MEDLINE (1990–2001), SPORT Discus (1949–2002), ERIC (1966–2002), and Internet Web sites were searched. Search terms included leadership, situational leadership, clinical instructors and leadership, teachers as leaders, and clinical education.

Data Synthesis: Situational Leadership is presented as a leadership model to be used by clinical instructors while teaching and supervising athletic training students in the clinical setting. This model can be implemented to improve the clinical-education process. Situational leaders, eg, clinical instructors, must have the flexibility and range of skills to vary their leadership styles to match the challenges that occur while teaching athletic training students.

Conclusions/Recommendations: This leadership style causes the leader to carry a substantial responsibility to lead while giving power away. Communication is one of the most important leadership skills to develop to become an effective leader. It is imperative for the future of the profession that certified athletic trainers continue to develop effective leadership skills to address the changing times in education and expectations of the athletic training profession.

Keywords: leadership, Situational Leadership, teacher as leader, clinical education

In athletic training education programs, professional skills and abilities are refined in the clinical-education component. This educational component relies heavily on the expertise and effectiveness of clinical instructors (CIs), who serve as teachers of clinical skills, and educational leaders, who pass on leadership behaviors while teaching, supervising, and mentoring athletic training students (ATSs). Given the vast range of ATSs' behavior variables, such as level of emotional maturity, competency, and commitment, CIs need to be able to adjust their leadership styles or strategies to best fit the students' observed needs in specific situations. Furthermore, effective clinical teaching is influenced by the CIs' leadership skills and abilities.1 As in other disciplines, CIs who are effective teachers demonstrate similar attributes and characteristics as effective leaders.2–6 Therefore, CIs who play a role in educating the future protégés of the athletic training profession must also develop their leadership styles and skills.

The purpose of this article is to present a leadership model, Situational Leadership (SL), which can be implemented by CIs during clinical education. The SL model can create or enhance the CIs' own leadership styles and enhance the use of their leadership skills and abilities in the clinical setting. The SL theory is based on a commonsense approach and is easily understood by all involved; thus, it is an appealing model for students and practitioners.7

DEFINING LEADERSHIP

Before we can understand leadership and its role in clinical education, we must first define leadership. Unfortunately, the definition of leadership takes on many forms, depending on the perspective and element discussed. A few pertinent definitions related to this discussion are presented. Leadership has been observed in all socioeconomic environments and at different hierarchic levels for a very long time.8 Typically, leadership positions are viewed as top-of-the-scale positions, such as presidents, chief executive officers, deans, department chairs, and program directors. Leadership also can be viewed in any position in which a person's followers “buy into” the leader's vision and work toward a set goal.8 Furthermore, leadership can be defined as the ability to induce others to take actions toward a common aspiration.9 Theory indicates that leadership consists of 3 elements: relation, leader driven, and action.9 In the relation element, more than 1 person is needed to create a leader; without followers, there is no leader. In the leader-driven element, a leader must do something or cause something to happen. The final element is that leadership requires followers to take action: leaders promote followers to increase productivity by using incentives, rewards, or team building, or conversely, by punishing.9 Finally, leadership can be defined as a relationship founded on trust and confidence that encourages people to take risks. Risks encourage change, and change keeps organizations alive.10 On the basis of these definitions, leaders have significant and responsible influence over followers. In the athletic training clinical-education process, CIs must assume the leadership positions as clinical teachers. Moreover, when CIs model effective teaching techniques and develop leadership expertise, they become effective teacher-leaders; they view leadership as an opportunity to positively affect their own growth and their students' learning.11

In summary, many definitions explain leadership. Each situation presents its own operational definition and description. Athletic training provides many different scenarios in which leaders emerge in various situations and positions. The focus here will be on CIs as leaders and teachers in clinical education, using the SL model.

CHARACTERISTICS OF EFFECTIVE LEADERS

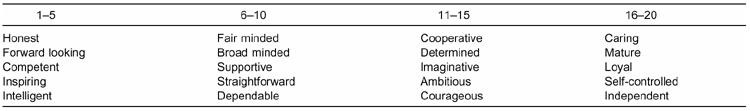

For many years, researchers who studied characteristics of effective leaders have found one common theme: leaders are agents of change.7 In the early 1980s, Kouzes and Posner10 researched more than 20 000 business and government executives, asking what the subordinates and leaders valued in a leader. They identified 5 top characteristics: (1) honest, (2) forward looking or visionary, (3) inspiring, (4) competent, and (5) fair minded. The top 20 characteristics from their most recent study are presented in Table 1. Other investigations of leadership studies identified similar characteristics and attributes.9,12–18

Table 1. Twenty Characteristics, Values, or Traits Identified in Effective Leaders in Rank Order10

LEADERSHIP THEORIES AND SITUATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Many theories and models have emerged throughout the decades of research in leadership. The leadership model presented in this article, which is easily applied in clinical education, is SL. Since the early 1960s, Hersey has researched and developed what is known as the SL model. This model is used by leaders to recognize current behaviors of people and motivate, facilitate, and encourage them to reach their highest levels of performance and potential.7,19 Situational leadership describes the relationship and task between the appropriate behavior and response by the leader based on the follower's maturity level. Again, the key to effective leadership lies in matching the appropriate behavior or style of the leader to the follower's maturity level.7,19

To be a good leader is to know your group and its members' abilities and willingness to perform tasks at all times. In addition, to be an effective leader, you must know how others perceive your leadership style and be aware of your own preferred style.16 Leadership in the clinical setting is just one aspect of leadership in athletic training educational programs. Again, effective leadership is not limited to the heads of organizations; it is employed at many levels within organizations and affects all personnel.19,20 In other words, athletic training CIs must know the skills and abilities of their entry-level ATSs to display effective leadership while they are teaching. As the students' cognitive abilities, emotional maturity, and levels of experience change, CIs should demonstrate multiple leadership practices in teachable situations and be ready to adapt their leadership style to any specific clinical situation. Furthermore, effective leaders identify the most effective leadership style for a given condition and adapt their leadership style accordingly.

There is a fine line between leadership strategies and clinical teaching methods, and parallels between leadership in the clinical setting and teaching styles can be seen. The following information is designed to lead readers to think about the leadership style and characteristics used by the CI during teachable situations. The leadership concepts that are described in the following section draw on effective leadership characteristics and behaviors and use the basic attributes of creating trust, building respect and commitment, enhancing communication skills, and demonstrating support between CIs and ATSs.

CLINICAL INSTRUCTORS AS SITUATIONAL LEADERS

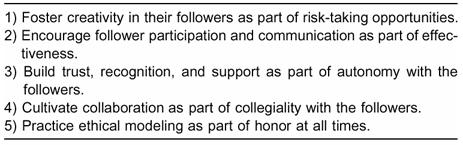

Situational Leadership can be easily implemented by athletic training instructors; this model takes a commonsense approach and is easy to understand.7 The advantages of SL for CIs are numerous because it promotes actions that are characteristic of teachers as leaders. These effective leadership behaviors (Table 2) can be shared with and taught to ATSs by CIs during clinical education. Many health science investigators have conducted empirical studies to review SL as an effective leadership style21–25; however, only one study (in nursing) applied SL to clinical education.23

Table 2. Behaviors Observed in Situational Leaders

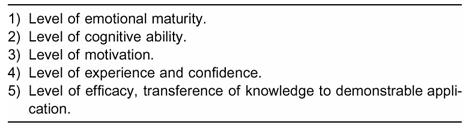

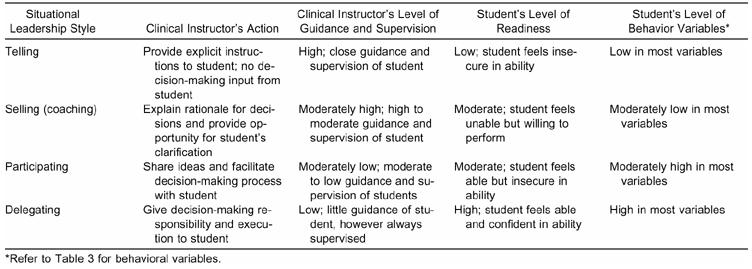

To be effective using the SL model, CIs must have the flexibility and range of leadership skills to vary their leadership style. The SL model includes 4 leadership styles that are appropriate for CIs to use with different observed behaviors identified in students: (1) telling, (2) selling, (3) participating, and (4) delegating.7,19 A situational leader adapts his or her leadership behaviors to match the features of the situation and levels of readiness of the followers. However, before a leadership style can be incorporated in a clinical-education situation, the ATSs' level of readiness should be assessed to determine the CI's best-fit leadership style. Readiness is defined as the ability and willingness of the followers to perform a specific task.7,19 Table 3 depicts the 5 variables that determine follower readiness and should be assessed by the CI before a leadership style is implemented.19 Once the student's level of readiness is determined, via observation or written assessment, the situational style that best fits the given situation for student readiness is then incorporated to promote growth and guide or challenge the student. Table 4 has been adapted from the works of Hersey et al19 and summarizes the 4 SL styles that match the follower's readiness levels with the appropriate leadership style.

Table 3. Students' Behavior Variables That Determine Situational Leadership Styles

Table 4. Clinical-Instructor Leadership Style Paired with Student's Level of Readiness (adapted from Situational Leadership Model)19

Telling and selling styles of the SL model may be appropriate for students who are in the beginning semesters of the athletic training education program and need strong guidance and supervision. The remaining 2 styles, participating and delegating, may be used with more experienced students because these ATSs have a sense of confidence and a greater knowledge base.

The telling style is appropriate when the followers are new or inexperienced and need direction and guidance to complete a specific task. In this case, the leader provides detailed instructions and closely supervises the followers' performance, all the while building trust and demonstrating straightforwardness. The leader unilaterally initiates problem-solving and decision-making processes.7,19 The telling leadership technique is most appropriate to use with beginning ATSs because these students have a low level of experience, confidence, and knowledge and a low to moderate level of maturity.

When teaching a beginning student to administer superficial heat clinically, the CI should be explicit and directive in the instructions given to the ATS. The student does not need to think deeply about the process of acting to a command but only reacts to that command. Additionally, the CI should dialog with the student to teach the guidelines of using superficial heat to foster student growth and advance the learning process. The CI not only teaches the clinical skills in this example but also communicates effectively and listens actively, all traits of an effective leader. Even though the CI performs the telling, or problem-solving and decision-making processes, the student still learns because of the quality communication and feedback between the CI and student. It is imperative to provide useful, level-specific feedback to foster learning, create a sense of confidence in the student, and advance the student to the next level of readiness (the ability and willingness to perform a task). In summary, the telling style provides the ATS with specific instructions and close supervision to ensure that quality learning occurs, and the CI communicates to cultivate knowledge and skills in the given task.

The next level of leadership is the selling style (also known as the coaching style). This style allows the leader to provide moderate to high direction to the student and lead by example. The leader now encourages the follower to express his or her own feelings and suggestions to solve a challenge. This style encourages 2-way communication. The ATS begins to become empowered, but the final decision remains with the CI. This style is useful when students are more responsible, experienced, and willing to do the task but may lack the necessary skills needed for independence in the given situation.7,19 For example, an athlete enters the athletic training facility before practice in need of superficial heat for a chronic quadriceps muscle injury. Through previous observation, the ATS recognizes the need to retrieve a hot pack for this athlete and communicates that need to the CI. In turn, the CI challenges the student's knowledge by asking pointed questions and suggesting several alternative treatment protocols or modalities from which the student might choose. This questioning challenges the student to decide the best method of treatment for this injury. By giving the appropriate feedback and receiving positive reinforcement from the CI, the student builds self-confidence. The CI gives moderate direction and supervision, but the student analyzes the problem, creates solutions, and explains and defines the rationale for the solutions. The CI still takes responsibility for the student's actions by approving or denying the student's suggested protocol. In the selling style, dialog between the CI and ATS is crucial; communication enhances the student's self-confidence and motivation, ensures the development of new skills, and increases cognitive ability and refining of previously learned skills. To summarize, key communication with moderate to high direction and high guidance from the leader to the follower characterizes the selling style.7,19

Next in SL is the participating style, which moves the student toward greater independence for autonomous performance. This style is characterized by low task or direction and high relationship behavior. In other words, the day-to-day decision-making and problem-solving tasks move from the leader (CI) to the follower (ATS). This style encourages the student to use his or her ability to perform the desired task, but the student may not be committed to starting or completing the assignment. Commitment in this context is defined as the student's level of motivation and confidence.7,19 A lack of commitment at this point in the student's development may be due to insecurity or a lack of confidence in newly acquired skills. For example, an athlete with hip pain enters the athletic training facility and approaches the ATS. The ATS is reluctant to assist this athlete, based on lack of experience and lack of confidence with this particular injury. The CI directs the ATS to assist the injured athlete and encourages the ATS to use previously acquired skills and knowledge. The ATS may ask the CI if a particular method of treatment that was used on another athlete with a similar injury should be administered, thus seeking approval and building confidence. The CI quizzes the ATS regarding the previous learning and, as a result, instills in the ATS a greater sense of self-confidence. Again, communication is key to further building the rapport between the CI and ATS and improving the student's learning. The CI continues to support the student's effort to use the skills already developed and further reinforces skills that were more recently acquired. Communication, confidence building, and supportive leadership characteristics are used in this example.

The final leadership style is the delegating style. This style is used when the followers are willing and able to take responsibility for directing their own behaviors. For instance, the CI and ATS discuss the challenge or situation, and a consensus of the exact problem is defined. Once both parties agree on the task, the decision-making process is delegated totally to the student. However, entire delegation to the student does not imply lack of involvement by the CI. This style allows the leader to focus attention on the next goal-setting task or problem identification for the follower.7,19 An ATS who has developed a broad knowledge base to this point has successfully performed designated skills in front of the CI and has reached the highest maturity level is encouraged to make clinical decisions with little guidance from the CI. Furthermore, it is imperative that the CI has “tested and challenged” the knowledge base, both the cognitive and psychomotor abilities of the ATS, before allowing him or her to become semiautonomous. Because the CI still must assume responsibility for the quality of care delivered by the ATS, supervision is still required.

Situations in athletic training change frequently, as does the student's knowledge base and readiness level; therefore, CIs should use a variety of leadership practices to educate and prepare students to accomplish the day's activities. In summary, the SL style used by the CI matches the evolution and progression of the student's readiness. When the student's ability and willingness are low, the CI uses the telling or selling styles (or both) to direct and guide the student to accomplish the task. Conversely, when the student's readiness level is high, the CI uses the participating or delegating styles (or both) to decrease control and allow the student to accomplish the goal with little direction.

CONCLUSIONS

Leadership is a fundamental element in clinical instruction. Situational leaders carry a substantial responsibility to lead and give power away as they encourage their followers in attaining their greatest potential. Again, leadership is not limited to the heads of organizations but is used at many levels within organizations. In clinical education, multiple leadership activities parallel a variety of clinical-instruction teaching methods; however, the actions or behaviors performed by clinical instructors are based on effective leader characteristics. These characteristics include creating trust, building respect and commitment, enhancing communication skills, and demonstrating support between themselves and their ATSs. The 4 styles that encompass SL are telling, selling, participating, and delegating. The level of readiness of the follower determines the style employed. As the ATS's level of readiness changes, so should the clinical instructor's leadership strategy.

REFERENCES

- Platt L S. Leadership Skills and Abilities, Professional Attributes, and Effectiveness in Athletic Training Clinical Instructors [dissertation] Duquesne University; Pittsburgh, PA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S T. Faculty and student perceptions of effective clinical teachers. J Nurs Educ. 1981;20:4–15. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19811101-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagler S, Loper-Powers S, Spitzer A. Clinical teaching is more than evaluation alone. J Nurs Educ. 1988;27:342–348. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19881001-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong C M, McCauley G T. Measuring the nursing, teaching, and interpersonal effectiveness of clinical instructors. J Nurs Educ. 1993;32:325–328. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19930901-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gien L T. Evaluation of faculty teaching effectiveness: toward accountability in education. J Nurs Educ. 1991;30:92–94. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19910201-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarski R W, Kulig K, Olsen R E. Clinical teaching in physical therapy: student and teacher perceptions. Phys Ther. 1990;70:173–178. doi: 10.1093/ptj/70.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R L, Ginnett R C, Curphy G J, Leading Organizations: Perspectives for a New Era . Contingency theories of leadership. In: Hickman G R, editor. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Bass B M. Bass & Stogdill's Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications. 3rd ed The Free Press; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Locke E A. The Essence of Leadership: The Four Keys to Leading Successfully. Lexington Books; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzes J M, Posner B Z. The Leadership Challenge. 3rd ed Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Merideth E M. Leadership Strategies for Teachers. SkyLight Training and Publishing Inc; Arlington Heights, IL: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Howell J, Avolio B J, Leading Organizations: Perspectives for a New Era . The ethics of charismatic leadership. In: Hickman G E, editor. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J E, Brookhart S M. Leader authenticity: key to organizational climate, health and perceived leader effectiveness. J Leadersh Stud. 1996;3:87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis W. On Becoming a Leader. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.; Reading, MA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stogdill R M. Handbook of Leadership: A Survey of Theory and Research. The Free Press; New York, NY: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy W K, Miskel C G. Educational Administration: Theory, Research and Practice. 5th ed McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tead O. The Art of Leadership. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl G. Leadership in Organizations. 4th ed Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey P, Blanchard K H, Johnson D E. Management of Organizational Behavior: Utilizing Human Resources. 7th ed Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio B J. Full Leadership Development. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss R G. Leadership theories and their implications for occupational therapy practice and education. Occup Ther Pract. 2000;5:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ketchum S M. Overcoming the four toughest management challenges: increase your effectiveness by using situational leadership. Clin Lab Manage Rev. 1991;5:246–247,250–251,254–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan M J, Hoover P S, Hoover R. Leadership: theory lets clinical instructors guide students toward autonomy. Nurs Health Care. 1988;9:82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucie D. Effective managerial leadership in sport organization. J Sport Manage. 1994;1:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Reed J F. Situational leadership. Nurs Manage. 1992;23:63–64. doi: 10.1097/00006247-199201000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]