Abstract

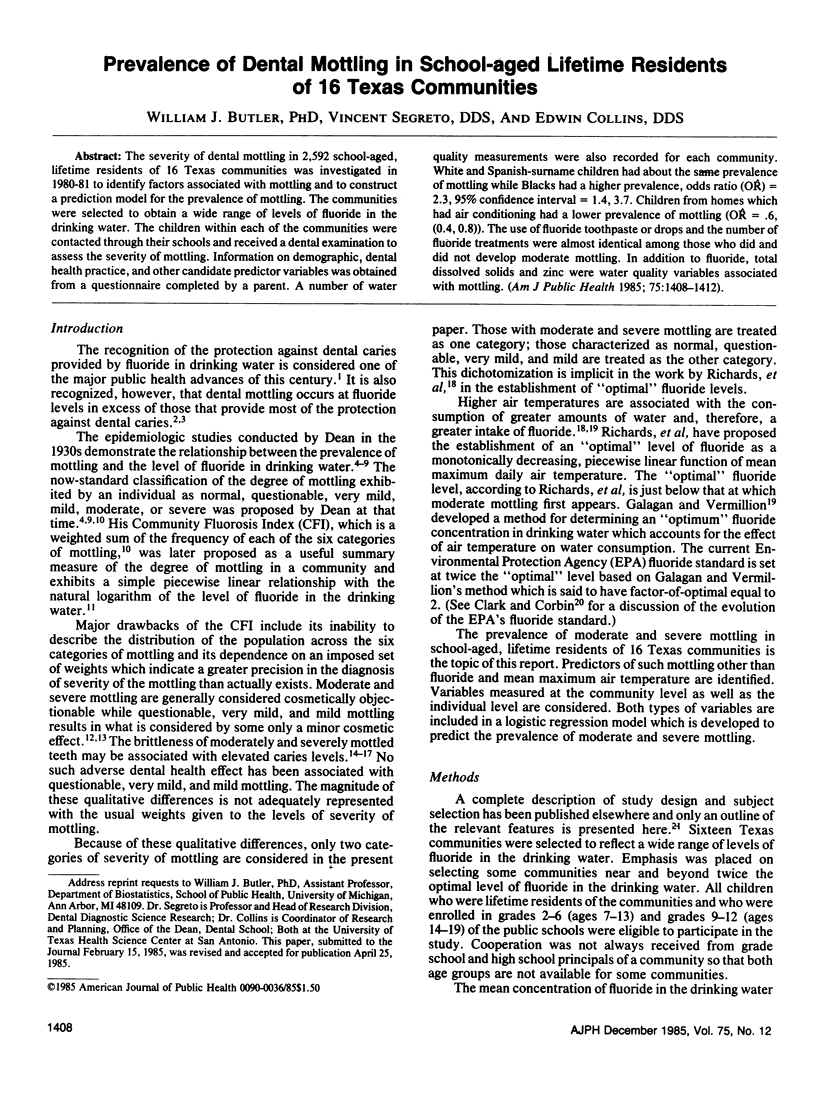

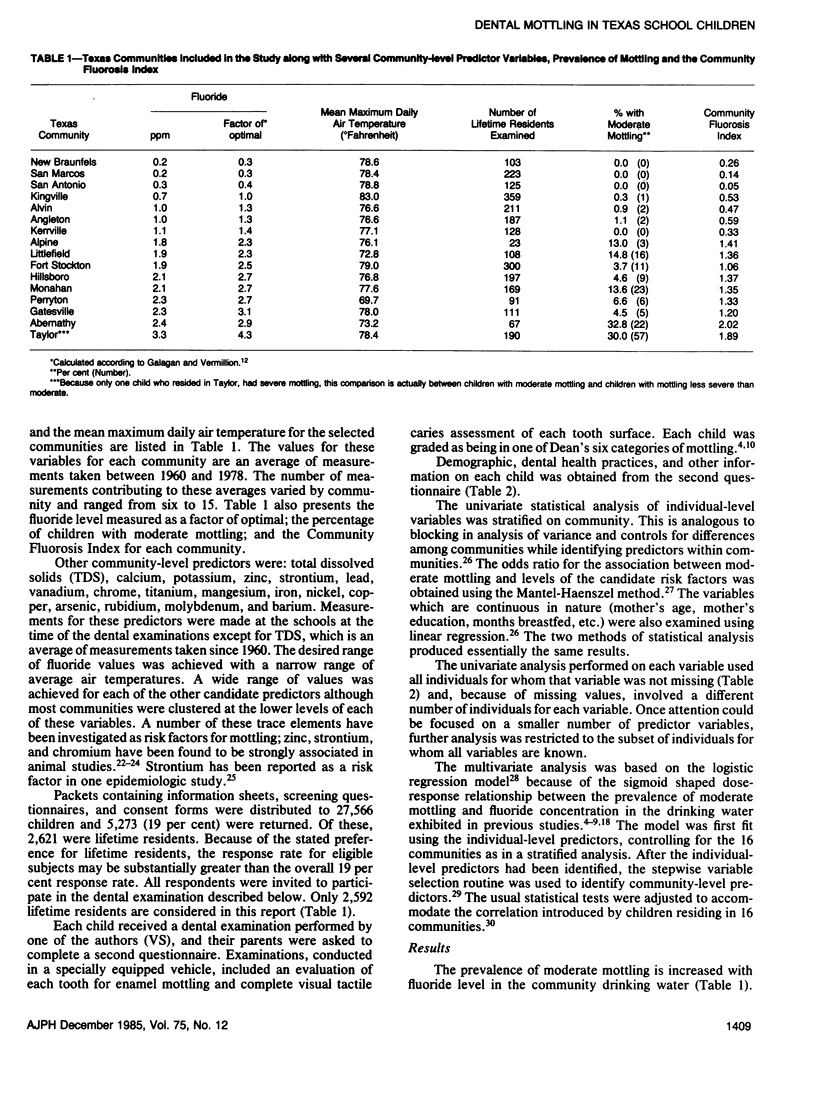

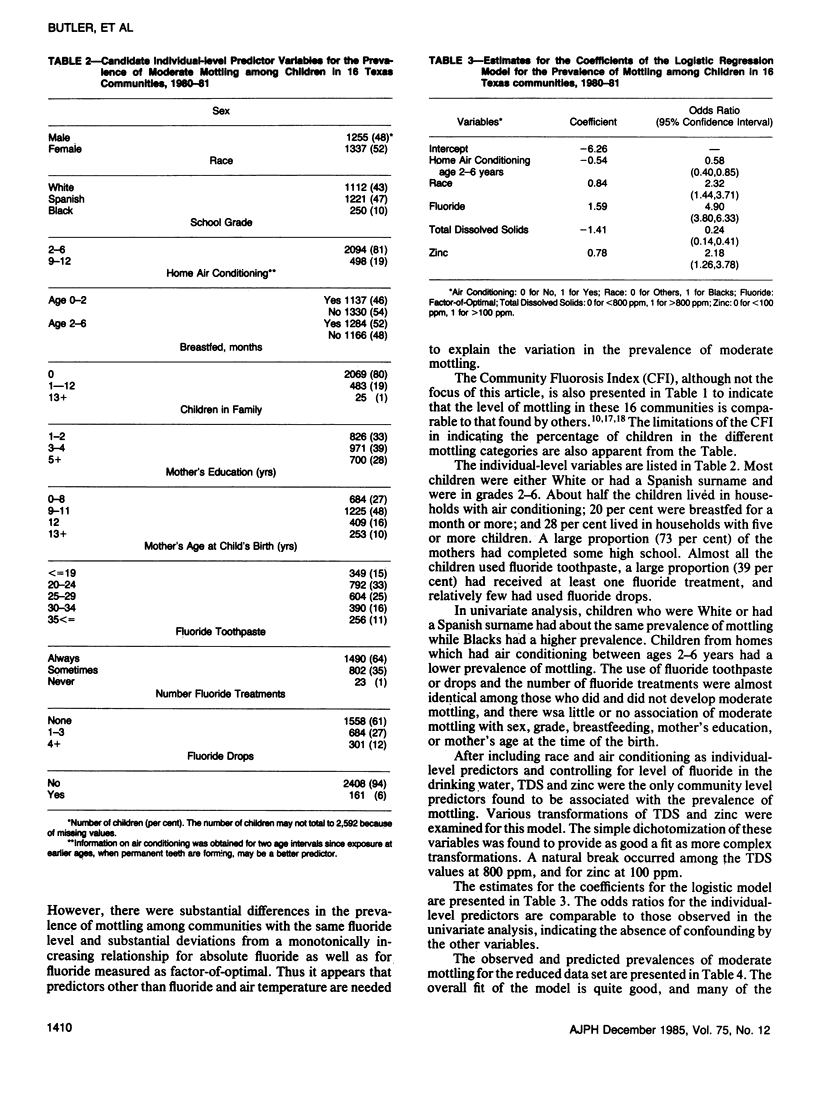

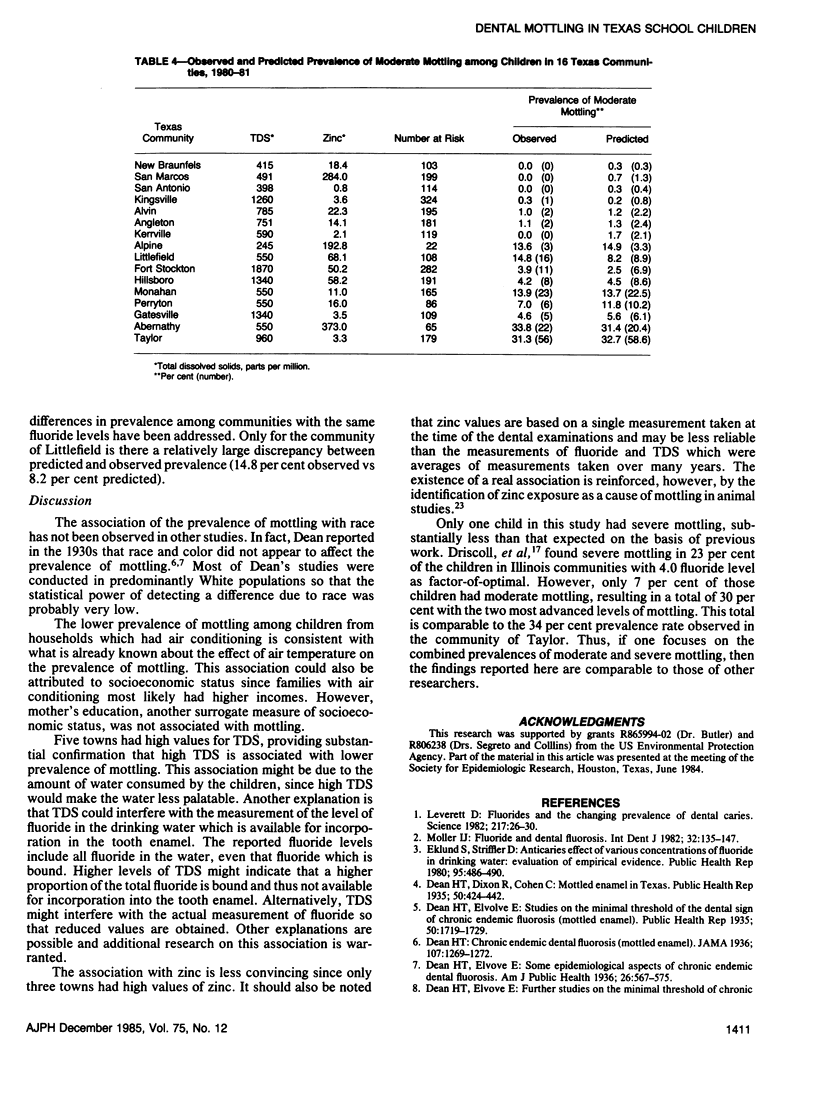

The severity of dental mottling in 2,592 school-aged, lifetime residents of 16 Texas communities was investigated in 1980-81 to identify factors associated with mottling and to construct a prediction model for the prevalence of mottling. The communities were selected to obtain a wide range of levels of fluoride in the drinking water. The children within each of the communities were contacted through their schools and received a dental examination to assess the severity of mottling. Information on demographic, dental health practice, and other candidate predictor variables was obtained from a questionnaire completed by a parent. A number of water quality measurements were also recorded for each community. White and Spanish-surname children had about the same prevalence of mottling while Blacks had a higher prevalence, odds ratio (OR) = 2.3, 95% confidence interval = 1.4, 3.7. Children from homes which had air conditioning had a lower prevalence of mottling (OR = .6, (0.4, 0.8)). The use of fluoride toothpaste or drops and the number of fluoride treatments were almost identical among those who did and did not develop moderate mottling. In addition to fluoride, total dissolved solids and zinc were water quality variables associated with mottling.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Clark N., Corbin S. The evolution of standards for naturally occurring fluorides: an example of scientific due process. Public Health Rep. 1983 Jan-Feb;98(1):53–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curzon M. E., Spector P. C. Enamel mottling in a high strontium area of the U.S.A. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1977 Sep;5(5):243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1977.tb01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean H. T., Elvove E. Some Epidemiological Aspects of Chronic Endemic Dental Fluorosis. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1936 Jun;26(6):567–575. doi: 10.2105/ajph.26.6.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll W. S., Horowitz H. S., Meyers R. J., Heifetz S. B., Kingman A., Zimmerman E. R. Prevalence of dental caries and dental fluorosis in areas with optimal and above-optimal water fluoride concentrations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983 Jul;107(1):42–47. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1983.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann D. R., Yaeger J. A. Alterations in the formation of rat dentine and enamel induced by various ions. Arch Oral Biol. 1969 Sep;14(9):1045–1064. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(69)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund S. A., Striffler D. F. Anticaries effect of various concentrations of fluoride in drinking water: evaluation of empirical evidence. Public Health Rep. 1980 Sep-Oct;95(5):486–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest J. R. Mottled enamel. Br Dent J. 1965 Oct 5;119(7):316–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman B. Dental fluorosis and caries in high-fluoride districts in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1974;2(3):132–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALAGAN D. J., VERMILLION J. R. Determining optimum fluoride concentrations. Public Health Rep. 1957 Jun;72(6):491–493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis J. R., Cooper M. M., Kennedy T., Koch G. G. A computer program for testing average partial association in three-way contingency tables (PARCAT). Comput Programs Biomed. 1979 May;9(3):223–246. doi: 10.1016/0010-468x(79)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverett D. H. Fluorides and the changing prevalence of dental caries. Science. 1982 Jul 2;217(4554):26–30. doi: 10.1126/science.7089534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller I. J. Fluorides and dental fluorosis. Int Dent J. 1982 Jun;32(2):135–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson B. Dental findings in high-fluoride areas in Ethiopia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1979 Feb;7(1):51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1979.tb01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Weekly Reports for DECEMBER 6, 1935. Public Health Rep. 1935 Dec 6;50(49):1719–1750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Weekly Reports for SEPTEMBER 10, 1937. Public Health Rep. 1937 Sep 10;52(37):1249–1295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retief D. H., Bradley E. L., Barbakow F. H., Friedman M., van der Merwe E. H., Bischoff J. I. Relationships among fluoride concentration in enamel, degree of fluorosis and caries incidence in a community residing in a high fluoride area. J Oral Pathol. 1979 Aug;8(4):224–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1979.tb01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. F., Westmoreland W. W., Tashiro M., McKay C. H., Morrison J. T. Determining optimum fluoride levels for community water supplies in relation to temperature. J Am Dent Assoc. 1967 Feb;74(3):389–397. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1967.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]