Abstract

The capsaicin receptor, TRPV1 (VR1), is a sensory neuron-specific ion channel that serves as a polymodal detector of pain-producing chemical and physical stimuli. Extracellular Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1 observed in patch–clamp experiments when using both heterologous expression systems and native sensory ganglia is thought to be one mechanism underlying the paradoxical effectiveness of capsaicin as an analgesic therapy. Here, we show that the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin binds to a 35-aa segment in the C terminus of TRPV1, and that disruption of the calmodulin-binding segment prevents TRPV1 desensitization. Compounds that interfere with the 35-aa segment could therefore prove useful in the treatment of pain.

Capsaicin elicits burning pain by activating specific (vanilloid) receptors on sensory nerve endings (1). The cloned capsaicin receptor, TRPV1 (VR1), a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel super family, is a nociceptive neuron-specific capsaicin-gated ion channel that also responds to heat, protons, anandamide, and lipoxygenase products (2–6). Furthermore, analysis of mice lacking TRPV1 showed that TRPV1 is essential for selective modalities of pain sensation and for tissue injury-induced thermal hyperalgesia, suggesting a critical role for TRPV1 in the detection or modulation of pain (7, 8). TRPV1-mediated depolarization of nociceptive afferents triggers the transmission of action potentials to the central nervous system as well as the release of inflammatory peptides from peripheral nociceptor terminals (1). Extracellular Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1 has been observed in patch–clamp experiments when using both heterologous expression systems and native sensory ganglia (1, 2, 9–12). The inactivation of nociceptive neurons by capsaicin has generated extensive research on the possible therapeutic effectiveness of capsaicin as a clinical analgesic tool (1, 13–15). Still, however, the underlying mechanism of this inactivation process is not known.

Desensitization to capsaicin is a complex process with varying kinetic components: a fast one that appears to depend on Ca2+ influx through the capsaicin receptor channels (9–12) and a slower component that does not. Previous studies have shown that calcineurin inhibitors reduce desensitization, indicating the involvement of Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation/dephosphorylation process (9), and protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of TRPV1 recently has been reported to mediate the slow component of TRPV1 desensitization (16). On the other hand, there have been several studies reporting that calmodulin (CaM) mediates Ca2+-dependent inhibition or inactivation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (17–19), NMDA receptor ion channels (20–22), L type Ca2+ channels (23–26), P/Q type Ca2+ channels (27, 28), and small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (29), many of which have high Ca2+ permeability. A 1.6-Å crystal structure of the gating domain of a small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel complexed with Ca2+/CaM was reported recently (30). Furthermore, several members of the TRP ion channel super family have been found to be regulated by CaM binding (31–38). Despite the fact that TRPV1 contains no obvious CaM-binding sites, such as a consensus isoleucine–glutamine motif, that TRPV1 is a member of the TRP ion channel super family suggests the possibility that CaM inactivates TRPV1 in a Ca2+-dependent manner. We report that CaM binds to a 35-aa segment of TRPV1 and that disruption of the CaM-binding segment prevents the desensitization.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis. A deletion mutant of TRPV1 lacking 35 aa (Δ35AA) was made by PCR. Rat CaM cDNA was obtained from the brain cDNA library (CLONTECH). Three CaM mutants, D21A/D57A (the first and second Ca2+-binding positions of all four EF hands), D94A/D130A (the third and fourth Ca2+-binding positions), and D21A/D57A/D94A/D130A were introduced by using oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. cDNAs were subcloned into pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen).

Mammalian Cell Culture. Human embryonic kidney-derived HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM (supplemented with 10% FBS/penicillin/streptomycin/L-glutamine) and transfected with 1 μg of plasmid DNA by using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen). TRPV1 cDNA was prepared as described (2).

Electrophysiology. Whole-cell patch–clamp recordings were carried out 1 or 2 days after transfection of TRPV1 cDNA to HEK293 cells as described above. Data were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz for analysis (Axopatch 200B amplifier with PCLAMP software, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Standard bath solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4 (adjusted with NaOH). In Ca2+-free bath solution, CaCl2 was replaced with 5 mM EGTA. Acid solution was buffered with 10 mM Mes instead of Hepes, and pH was adjusted to 4.0. Pipette solution contained 140 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 (adjusted with KOH). All patch-clamp experiments were performed at room temperature (22°C). The solutions containing drugs were applied to the chamber (180 μl) by gravity at a flow rate of 5 ml/min.

In Vivo Binding Assay. HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM and plated at 60–70% confluence in 100-mm dishes and then transfected with 0.5 μg of rat TRPV1 cDNA or vector (pcDNA3) and 0.5 μg of Myc-tagged rat CaM cDNA, as described above. Thirty-six hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 1 μM capsaicin at 37°C for 3 min. After treatment with capsaicin, the cells were washed and suspended with ice-cold PBS. Onetenth of the samples were centrifuged and resuspended in SDS sample buffer (total cell lysate). The remaining samples were resuspended in TNE buffer [10 mM Tris·HCl/150 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA/complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)] with 2 mM CaCl2 and centrifuged for 15 min at 100,000 × g. The pellets were suspended in TNE buffer with 1% Nonidet P-40 and 2 mM CaCl2 and then sonicated for 30 sec. After the centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatants were precleared with protein A and then incubated at 4°C for 3 h with 4 μg of rabbit anti-rat TRPV1 antibodies. Anti-rabbit IgG was added and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Total cell lysate and the immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-TRPV1 or anti-Myc antibodies (QE10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). A peptide encoding the predicted carboxyl terminus of TRPV1 (EDAEVFKDSMVPGEK) was coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin via an amino-terminal cysteine and used to immunize rabbits.

In Vitro Binding Assay. Fusion proteins comprising GST at the N terminus in-frame with N terminus, the first intracellular loop, the second intracellular loop, C terminus, four segments in C terminus (Fig. 2), and C terminus lacking 35 aa were generated by PCR and standard cloning techniques. The PCR products were subcloned into the pGEX vector (Amersham Biosciences). The final constructs were verified by sequencing. GST-TRPV1 proteins were purified according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Biosciences). The GST pull-down assay was performed by mixing the GST-TRPV1 proteins and 5 μg of bovine brain CaM (Calbiochem) in binding buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl/100 nM NaCl/1 mM EDTA/0.1% Triton-X/complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)] with [Ca(+)] or without [Ca(-)] 2 mM CaCl2. EGTA (5 mM) was added to the Ca(-) binding buffer. After a 2-h incubation at 4°C, the beads and bound materials were washed extensively and analyzed by SDS/PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) and immunoblotting by anti-CaM antibodies (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY).

Fig. 2.

In vivo and in vitro interaction of calmodulin with TRPV1. (A) TRPV1 immunoprecipitation analysis in HEK293 cells transfected with Myc-tagged CaM and TRPV1 or pcDNA3 with or without capsaicin (Cap) treatment (1 μM, 3 min) in the presence of Ca2+. CaM was coimmunoprecipitated with TRPV1 depending on Cap treatment. Similar CaM expression was confirmed in both pcDNA3- and TRPV1-transfected cells regardless of Cap treatment. (B) Analysis of CaM binding to cytoplasmic domains of TRPV1 by using a GST pull-down assay in the presence of Ca2+. Only the C terminus of TRPV1 was found to interact with CaM. (C) Identification of a CaM-binding segment in the C terminus of TRPV1 by using a GST pull-down assay in the presence of Ca2+. Four C-terminal segments of TRPV1 used for making GST-fusion proteins are shown in the context of a putative transmembrane topology model (Left). (Right) A pull-down assay using GST-fusion proteins with four segments. (D) GST pull-down assays with C terminus of TRPV1 (Left), C terminus lacking 35 aa (Left), and segment 2 of C terminus (Right) in the presence (+) or absence (-) of Ca2+.

Chemicals. 1,2-Bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid and (N-[2-(N-(4-chlorocinnamyl)-N-methylaminomethyl)phenyl]-N-{2-hydroxyethyl}-4-methoxybenzenesulfonamide) (KN93), Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II inhibitor, were purchased from Sigma. Two CaM inhibitors, N-(6-aminohexyl)-1-naphthalenesulfonamide hydrochloride (W-7) and calmidazolium chloride, were purchased from Seikagaku Kogyo (Tokyo) and Calbiochem, respectively.

Results

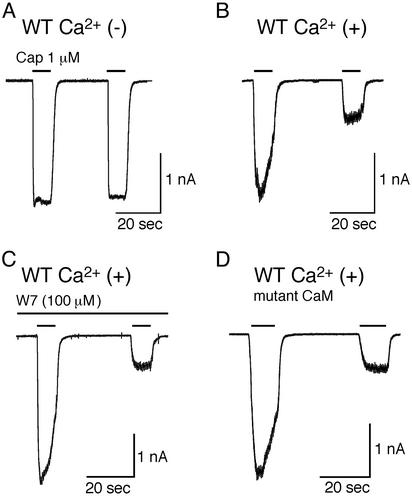

In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, little reduction of capsaicin-activated currents was observed on short (10-sec) repetitive application [amplitude of second response was 95.5 ± 1.6% (mean ± SE) of the first, n = 4] (Fig. 1A) in HEK293 cells expressing WT TRPV1. On the other hand, a prominent reduction in the amplitude of capsaicin-activated currents (desensitization) was detected in the presence of 2 mM extracellular Ca2+ (23.9 ± 7.5% of the first response, n = 4, P < 0.01 vs. without Ca2+) (Fig. 1B), as described (1, 2). We examined the amplitude of the desensitized currents at 30 sec, 2 min, 5 min, and 10 min after the initial brief capsaicin application. Intracellular Ca2+ concentration is supposed to resume its resting level at these time points. However, no recovery was observed (22.0 ± 4.6% of the first response at 10 min, n = 3), suggesting that the Ca2+-dependent structural change of TRPV1, if any, may be hard to reverse once it occurs. To confirm the importance of intracellular Ca2+ for the capsaicin-evoked desensitization, we examined the effect of 10 mM 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, a potent Ca2+ chelator, in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ in HEK 293 cells expressing TRPV1. However, this compound failed to prevent TRPV1 desensitization (data not shown), suggesting that the site of Ca2+ action for desensitization, if there is one, must be very close to the channel pore through which Ca2+ enters. Next, we examined the potential involvement of CaM in TRPV1 desensitization. CaM inhibitor, W-7, or calmidazolium included in the pipette solution could not prevent TRPV1 desensitization (14.8 ± 3.1%, n = 8 for W-7, P < 0.01 vs. without Ca2+; 27.9 ± 9.5%, n = 5 for calmidazolium, P < 0.01 vs. without Ca2+) (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Cotransfection of TRPV1 with the three CaM mutants in their EF hands lacking Ca2+-binding ability (D21A/D57A, D94A/D130A, and D21A/D57A/D94A/D130A) also failed to prevent TRPV1 desensitization (23.0 ± 4.9%, n = 6; 31.5 ± 8.4%, n = 4; 26.5 ± 7.6%, n = 4, respectively, P < 0.01 vs. without Ca2+) (Fig. 1D). In addition, application of W-7 or calmidazolium was without effects on TRPV1 desensitization in the cells expressing TRPV1 and mutant CaMs (data not shown). These results suggest that CaM is not likely involved in Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1.

Fig. 1.

Extracellular Ca2+ dependence of capsaicin receptor current desensitization. (A and B) Representative traces of capsaicin-evoked whole-cell currents by short, repetitive application in HEK293 cells expressing WT TRPV1 in the absence (A) or presence (B) of extracellular Ca2+. Cells were held at -60 mV. (C) Representative trace of WT TRPV1 current evoked by capsaicin with CaM inhibitor W7 (100 μM) in the pipette solution in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. (D) Representative trace of capsaicin-evoked current in cells expressing WT TRPV1 and mutated CaM (D21A/D57A/D94A/D130A) in the presence of extracellular Ca2+.

However, we examined the direct interaction of TRPV1 with CaM biochemically because negative results with such inhibitors have been reported in some electrophysiological studies in other channels (39–41). In HEK293 cells expressing both TRPV1 and Myc-tagged CaM, CaM could be coimmunoprecipitated with TRPV1 in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the amount of CaM coimmunoprecipitated with TRPV1 was increased on capsaicin treatment. This finding suggests that an increased Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 results in making Ca2+/CaM complex, leading to TRPV1 desensitization.

To confirm that such an interaction occurs and to identify the domains of TRPV1 involved, recombinant proteins carrying GST fused to the four cytoplasmic domains of TRPV1 were generated for use in an in vitro binding assay with CaM in the presence of Ca2+. This assay demonstrated that the C terminus of TRPV1 contains the segment necessary for interaction with CaM (Fig. 2B). To further narrow down the amino acids involved, GST was fused to the four segments of the C terminus (Fig. 2C Left), and the resultant fusion proteins were subjected to the in vitro binding assay in the presence of Ca2+. Segment 2 was found to be sufficient for this interaction (Fig. 2C Right). In addition, the C terminus of TRPV1 lacking an internal 35-aa segment (E767-T801) (segment 2 in Fig. 2C; 44 aa minus overlapping 9 aa: EGVKRTLSFSLRSGRVSGRNWKNFALVPLLRDAST) failed to bind CaM, either in the presence or absence of Ca2+, further indicating that this 35 aa is essential for binding of TRPV1 with CaM (Fig. 2D Left).

We also found Ca2+ dependency of this interaction in an in vitro binding assay with or without Ca2+ by using GST-fusion proteins with the C terminus of TRPV1 lacking the 35 aa and segment 2 in the C terminus (Fig. 2D). Binding of CaM with the C terminus or segment 2 of TRPV1 was Ca2+-dependent, a phenomenon in agreement with the reported importance of Ca2+ for CaM function. Notably, the interaction of TRPV1 with CaM could be observed in the absence or presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 2D), suggesting that Ca2+ passing through the TRPV1 channels can act on CaM already bound to TRPV1. Also, that segment 2 of TRPV1 could bind to CaM in the absence of Ca2+ indicates that Ca2+-unbound CaM binds to segment 2.

The functional importance of this 35-aa segment was examined by using the patch–clamp technique in HEK293 cells expressing either WT TRPV1 or Δ35AA. The amount of Ca2+ entering the cell through the channel might be one of the determinants affecting the TRPV1-inactivation rates (16). Therefore, we decided to compare desensitization in cells expressing the different forms of TRPV1 (WT vs. mutant) but exhibiting similar current densities. Interestingly, in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, the desensitization induced by short capsaicin applications was almost completely abolished in the Δ35AA mutant (23.9 ± 7.5%, n = 4, 244 ± 46 pA/pF for WT; 93.3 ± 5.5%, n = 4, 243 ± 120 pA/pF for the mutant; P < 0.01) (Fig. 3 A and C), indicating that the 35-aa segment plays an important role in desensitization to such short, repetitive stimuli. Electrophysiological properties including outwardly rectifying IV relation and capsazepine sensitivity were unchanged in the mutant (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

CaM-binding segment of TRPV1 is sufficient for the extracellular Ca2+-dependent desensitization. (A) Representative trace of capsaicin-evoked current by short, repetitive application in HEK293 cells expressing deletion mutant of TRPV1 (Δ35AA) in the presence of extracellular Ca2+.(B) Representative traces of current responses evoked by long application of capsaicin in cells expressing WT TRPV1 (Left and Center)or Δ35AA (Right) in the absence (Left) or presence (Center and Right) of Ca2+. (C and D) Extent of desensitization summarized from the data in the short application (C) and the long application (D) protocol. The current ratios (mean ± SE) of the second to the first of two consecutive, 10-sec applications with a 30-sec interval (C) or the residual fractions (mean ± SE) of peak currents remaining at application of 1 μM capsaicin for 30 sec (D) are shown. *, P < 0.01 vs. WT TRPV1 with Ca2+; **, P < 0.01 vs. Δ35AA, two-tailed unpaired t test. (E) Effects of deleting a CaM-binding domain on desensitization of the TRPV1 currents induced by short, repetitive acid stimulations in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. The ratios (mean ± SE) of the second to the first of two consecutive, 10-sec applications of acidic solution (pH 4.0) are shown. *, P < 0.01 vs. WT TRPV1 with Ca2+; /#, P < 0.05 vs. WT TRPV1 with Ca2+, two-tailed unpaired t test.

Because it has been proposed that desensitization is kinetically complex, we also examined the effects of the 35-aa segment on TRPV1 currents evoked by long-duration (40-sec) capsaicin application. In cells expressing WT TRPV1, during a protracted capsaicin application, little reduction in the amplitude of capsaicin-activated currents was observed in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ [remaining current (mean ± SE): 92.3 ± 4.0%, n = 4, 465 ± 90 pA/pF] (Fig. 3B Left), whereas in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, a considerable time-dependent reduction in current amplitude was observed (7.1 ± 0.9%, n = 4, 382 ± 101 pA/pF, P < 0.01 vs. without Ca2+) (Fig. 3 B Center and D), as described previously (1, 2). In contrast, although some desensitization was observed in currents generated by the Δ35AA mutant in response to protracted capsaicin exposure, the extent of desensitization was significantly smaller than that exhibited by WT TRPV1 (24.0 ± 2.4%, n = 6, 245 ± 102 pA/pF, P < 0.01 vs. WT TRPV1 without Ca2+ and WT TRPV1 with Ca2+) (Fig. 3 B Right and D). These findings suggest that the fast component of TRPV1 desensitization involves the 35-aa segment but that this effect, in turn, can influence the extent of the slow component.

We next sought to determine whether the 35-aa-mediated desensitization was operative in the context of stimulation by other TRPV1 ligands such as protons, which activate TRPV1 through interaction with a different site than capsaicin (42). Whereas WT TRPV1 showed significant desensitization in response to short, repetitive exposure to protons, protonactivated currents mediated by the Δ35AA desensitized very little in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ [ratio (mean ± SE) of the second to the first of two consecutive responses: 86.8 ± 6.2% for WT without Ca2+, n = 4, P < 0.05 vs. WT with Ca2+; 67.0 ± 3.1% for WT with Ca2+, n = 4; 100.8 ± 7.0% for Δ35AA with Ca2+, n = 4, P < 0.01 vs. WT with Ca2+) (Fig. 3E). This finding indicates that the 35-aa-mediated effect is not ligand-specific.

An earlier study has suggested the involvement of Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation in the Ca2+-dependent desensitization of capsaicin-induced currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons (9). Therefore, we examined the effect of CaMKII inhibitor, KN93, on desensitization of the TRPV1 currents induced by both short and long applications of capsaicin in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. We found that KN93 did not show any effects on the desensitizing properties (28.0 ± 11.7% of the first response, n = 6, and 7.1 ± 4.0% of the peak response, n = 5, for short and long capsaicin application, respectively), suggesting that CaMKII is not involved in the Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1, at least in the patch-clamp conditions we used.

Discussion

The results presented here identify a structural determinant involved in extracellular Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1. Ca2+-dependent desensitization is a relatively common feature of many cation channels including l-type Ca2+ channels, NMDA receptor channels, and TRP channels including TRPV1. It may be a physiological safety mechanism against a harmful Ca2+ overload in the cell, especially during large Ca2+ influx through the channels, and it is reported to be involved in phototransduction in Drosophila in some TRP channels. Feedback inhibition of NMDA receptor activity by Ca2+-dependent process is believed to allow for the regulation of Ca2+ influx in the postsynaptic cell. Similar regulation of Ca2+ flux through TRPV1 might play a role in the establishment of sensory neuron activation threshold and in the protection of these neurons from Ca2+ overload. The desensitization may induce refractoriness of sensory neurons to other noxious stimuli, leading to the use of capsaicin as an analgesic agent.

The Ca2+ dependence of CaM binding to TRPV1 (Fig. 2B) might be notable because Ca2+ entering through the channel can make CaM/Ca2+ complex, leading to the initiation of the channel inactivation. However, weak CaM binding to TRPV1 also was detected even in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 2D). This finding is in good agreement with a model in which CaM is tethered constitutively to the L type Ca2+ channels in a Ca2+-independent manner, a conclusion drawn from an experiment with Ca2+-insensitive CaM in which all four Ca2+-binding sites were mutated (25). Local tethering of CaM to the channels might ensure a relatively rapid response to a local Ca2+ signal (39). No putative Ca2+-binding EF hand motif or consensus CaM-binding isoleucine–glutamine motif was revealed to be involved in the interaction of CaM with TRPV1. Several amino acid sequences other than isoleucine–glutamine motif could be targets for CaM binding as suggested in L type Ca2+ channels (23). In our experiment, three kinds of mutant CaMs could not prevent Ca2+-dependent desensitization although those CaM mutants were reported to prevent the desensitization of several ion channels (24, 25, 28, 29, 37, 38). The reason for the negative results with mutant CaMs is not clear. Together with the ineffectiveness of the CaM inhibitors, W-7 and calmidazolium, the negative results might make it unlikely that CaM is involved in Ca2+-dependent TRPV1 desensitization. It is also less likely that endogenous CaM is sufficient for making CaM/Ca2+ complex show its effect. It remains a more likely mechanism for TRPV1 desensitization that the 35-aa segment disrupted in TRPV1 has another function independent of CaM binding. However, some endogenous CaM might not be affected by the two CaM inhibitors. Alternatively, prebound CaM might be insensitive to the inhibitors. Furthermore, there are many reports of negative results with the inhibitors, especially in the patch-clamp experiments. Therefore, we still cannot exclude the possibility that binding of CaM/Ca2+ complex to the 35-aa segment causes desensitization. Future studies will clarify this point and how the interaction between CaM and the 35-aa segment demonstrated in in vitro experiments relates to the importance of the segment for TRPV1 desensitization.

The desensitization of capsaicin-activated currents in sensory neurons was reported previously to be due to the activation of Ca2+-dependent phosphatase, calcineurin (PP2B) (9). That finding is consistent with the observation that TRPV1 can be phosphorylated by either PKA or PKC (16, 43, 44). In a recent study, it was reported that capsaicin receptors exist in the phosphorylated state in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (45). We have ruled out the possibility that CaMKII is involved in the Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1 although CaM involvement suggested it. Future studies aimed at exploring the role of Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation/dephosphorylation processes in the desensitization of recombinant TRPV1 may clarify further the mechanistic basis.

In conclusion, we identified a structural determinant of TRPV1 that interacts with CaM. The interaction may underlie, in part, the paradoxical use of capsaicin as analgesic. Moreover, compounds acting on the 35-aa segment of TRPV1 could prove useful in the treatment of pain by interfering with Ca2+/CaM function.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. J. Caterina (The Johns Hopkins University) for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan and the Japan Brain Foundation, and by the Uehara Memorial Foundation (M.T.) and the Maruishi Pharmaceutical Company, Limited (Japan).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CaM, calmodulin; TRP, transient receptor potential; Δ35AA, deletion mutant of TRPV1 lacking 35 aa.

References

- 1.Szallasi, A. & Blumberg, P. M. (1999) Pharmacol. Rev. 51, 159-211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caterina, M. J., Schumacher, M. A., Tominaga, M., Rosen, T. A., Levine, J. D. & Julius, D. (1997) Nature 389, 816-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tominaga, M., Caterina, M. J., Malmberg, A. B., Rosen, T. A., Gilbert, H., Skinner, K., Raumann, B. E., Basbaum, A. I. & Julius, D. (1998) Neuron 21, 531-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zygmunt, P. M., Petersson, J., Andersson, D. A., Chuang, H.-H., Sorgard, M., Di Marzo, V., Julius, D. & Hogestatt, E. D. (1999) Nature 400, 452-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang, S. W., Cho, H., Kwak, J., Lee, S.-Y., Kang, C.-J., Jung, J., Cho, S., Min, K. H., Suh, Y.-G., Kim, D., et al. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6155-6160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caterina, M. J. & Julius, D. (2001) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 487-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caterina, M. J., Leffler, A., Malmberg, A. B., Martin, W. J., Trafton, J., Petersen-Zeitz, K. R., Koltzenburg, M., Basbaum, A. I. & Julius, D. (2000) Science 288, 306-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis, J. B., Gray, J., Gunthorpe, M. J., Hatcher, J. P., Davey, P. T., Overend, P., Harries, M. H., Latcham, J., Clapham, C., Atkinson, K., et al. (2000) Nature 405, 183-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Docherty, R. J., Yeats, J. C., Bevan, S. & Boddeke, H. W. (1996) Pflügers Arch. 431, 828-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koplas, P. A., Rosenberg, R. L. & Oxford, G. S. (1996) J. Neurosci. 17, 3525-3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, L. & Simon, S. A. (1996) J. Neurophysiol. 75, 1503-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piper, A. S., Yeats, J. C., Bevan, S. & Docherty, R. J. (1999) J. Physiol. 518, 721-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein, J. E. (1987) Cutis 39, 352-353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maggi, C. A. (1991) J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 33, 1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell, E., Bevan, S. & Dray, A. (1993) in Capsaicin in the Study of Pain, ed. Wood, J. N. (Academic, San Diego), pp. 255-269.

- 16.Bhave, G., Zhu, W., Wang, H., Brasier, D. L., Oxford, G. S. & Gereau, R. W., IV. (2002) Neuron 35, 721-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman, A. L. (1995) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 5, 296-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molday, R. S. (1996) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 6, 445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grunwald, M. E., Yu, W.-P., Yu, H.-H. & Yau, K.-W. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9148-9157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehlers, M. D., Zhang, S., Bernhardt, J. P. & Huganir, R. L. (1996) Cell 84, 745-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang, S., Ehlers, M. D., Bernhardt, J. P., Su, C.-T. & Huganir, R. (1998) Neuron 21, 443-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krupp, J. J., Vissel, B., Thomas, C. G., Heinemann, S. F. & Wesrbrook, G. L. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 1165-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuhlke, R. D. & Reuter, H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 3287-3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuhlke, R. D., Pitt, G. S., Deisseroth, K., Tsien, R. W. & Reuter, H. (1999) Nature 399, 159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson, B. Z., DeMaria, C. D. & Yue, D. T. (1999) Neuron 22, 549-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin, N., Olcese, R., Bransby, M., Lin, T. & Birnbaumer, L. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2435-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, A., Wong, S. T., Gallagher, D., Li, B., Strom, D. R., Scheuer, T. & Catterall, W. (1999) Nature 399, 155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demaria, C. D., Soong, T. W., Alseikhan, B. A., Alvania, R. S. & Yue, D. T. (2001) Nature 411, 484-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia, X.-M., Fakler, B., Rivard, A., Wayman, G., Johnson-Pais, T., Keen, J. E., Ishii, T., Hirschberg, B., Bond, C. Y., Lutsenko, S., et al. (1998) Nature 395, 503-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumacher, M. A., Rivard, A. F., Bachinger, H. P. & Adelman, J. P. (2001) Nature 410, 1120-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warr, C. G. & Kelly, L. E. (1996) Biochem. J. 314, 497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott, K., Sun, Y., Beckingham, K. & Zuker, C. S. (1997) Cell 91, 375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chevesich, J., Kreuz, A. J. & Montell, C. (1997) Neuron 18, 95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemeyer, B. A., Bergs, C., Wissenbach, U., Flockerzi, V. & Trost, C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3600-3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trost, C., Bergs, C., Himmerkus, N. & Flockerzi, V. (2001) Biochem. J. 355, 663-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang, J., Lin, Y., Zhang, Z., Tikunova, S., Birnbaumer, L. & Zhu, M. X. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21303-21310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang, Z., Tang, J., Tikunova, S., Johnson, J. D., Chen, Z., Qin, N., Dietrich, A., Stefani, E., Birnbaumer, L. & Zhu, M. X. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3168-3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh, B. B., Liu, X., Tang, J., Zhu, M. X. & Ambudkar, I. S. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 739-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levitan, I. B. (1999) Neuron 22, 645-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Victor, R. G., Rusnak, F., Sikkink, R., Marban, E. & O'Rourke, B. (1997) J. Membr. Biol. 156, 53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imredy, J. P & Yue, D. T. (1994) Neuron 12, 1301-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jordt, S.-E., Tominaga, M. & Julius, D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8134-8139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Numazaki, M., Tominaga, T., Toyooka, H. & Tominaga, M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13375-13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rathee, P. K., Distler, C., Obreja, O., Neuhuber, W., Wang, G. K., Wang, S.-Y., Nau, C. & Kress, M. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 4740-4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vellani, V., Mapplebeck, S., Moriondo, A., Davis, J. B. & McNaughton, O. A. (2001) J. Physiol. 534, 813-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]