Abstract

In this paper, the Arrhenius curves of selected hydrogen-transfer reactions for which kinetic data are available in a large temperature range are reviewed. The curves are discussed in terms of the one-dimensional Bell–Limbach tunnelling model. The main parameters of this model are the barrier heights of the isotopic reactions, barrier width of the H-reaction, tunnelling masses, pre-exponential factor and minimum energy for tunnelling to occur. The model allows one to compare different reactions in a simple way and prepare the kinetic data for more-dimensional treatments. The first type of reactions is concerned with reactions where the geometries of the reacting molecules are well established and the kinetic data of the isotopic reactions are available in a large temperature range. Here, it is possible to study the relation between kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) and chemical structure. Examples are the tautomerism of porphyrin, the porphyrin anion and related compounds exhibiting intramolecular hydrogen bonds of medium strength. We observe pre-exponential factors of the order of kT/h≅1013 s−1 corresponding to vanishing activation entropies in terms of transition state theory. This result is important for the second type of reactions discussed in this paper, referring mostly to liquid solutions. Here, the reacting molecular configurations may be involved in equilibria with non- or less-reactive forms. Several cases are discussed, where the less-reactive forms dominate at low or at high temperature, leading to unusual Arrhenius curves. These cases include examples from small molecule solution chemistry like the base-catalysed intramolecular H-transfer in diaryltriazene, 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)-benzoxazole, 2-hydroxy-phenoxyl radicals, as well as in the case of an enzymatic system, thermophilic alcohol dehydrogenase. In the latter case, temperature-dependent KIEs are interpreted in terms of a transition between two regimes with different temperature-independent KIEs.

Keywords: tunnelling, kinetic isotope effects, solid state, nuclear magnetic resonance, relaxometry

1. Introduction

The mechanism of H-transfer from carbon to other heavy atoms in enzymes has become an important phenomenon of current interest (Basran et al. 2006; Kohen 2006). Large kinetic hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) isotope effects of the order of 10–100 at room temperature and concave curvatures of Arrhenius curves indicate tunnelling of hydrogen nuclei through the reaction barrier. Traditionally, kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) have been described theoretically in terms of a combination of isotope fractionation and transition state theory (TST; Bigeleisen 1949, 1955). In this theory, KIEs arise mainly from zero-point energy (ZPE) changes between the initial and the transition state (TS). The contribution of tunnelling to H-transfer reactions has been described by Bell (1973, 1980). His one-dimensional ‘Bell tunnelling model’ has been very successfully applied to explain kinetic H/D isotope effects using adaptable parameters. As kinetic data obtained for liquid solutions mostly refer to only a small temperature range, often only the so-called ‘Bell tunnelling correction’ to the classical KIEs has been used, which is easily mistaken for the ‘full’ Bell tunnelling model. A two-dimensional empirical tunnelling model has been developed in the 1970s by Dogonadze, Kuznetsov & Ulstrup (Bruniche-Olsen et al. 1979; German et al. 1980; Kuznetsov & Ulstrup 1999, 2006) and modified recently (Knapp et al. 2002) for use in enzyme reactions. Siebrand et al. (1984a,b) have proposed a golden rule treatment of H-transfer between the eigenstates of the reactants and products, where low-frequency vibrations play an important role that modifies the heavy atom distances. Limbach et al. (2004b) have modified the Bell tunnelling model for use in a variety of cases, including multiple H-transfer reactions, and have pointed out how this model performs reduction from two dimensions to one dimension. A number of quantum-mechanical theories have been proposed, which allow one to calculate isotopic Arrhenius curves from first principles, where tunnelling is included. These theories generally start with an ab initio calculation of the reaction surface and use either quantum or statistical rate theories in order to calculate rate constants and KIEs. Among these are the ‘variational TST’ (Truhlar 2006), the ‘instanton’ approach (Smedarchina et al. 2005), a Redfield-relaxation-type theory (Brackhagen et al. 1998), the ‘protein-promoting vibration’ (Antoniou & Schwartz 2001), and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) simulations (Olsson et al. 2003, 2004; Hatcher et al. 2004). Unfortunately, these methods are generally not available for the experimentalist at the stage when he needs to simulate his Arrhenius curves. For this stage, empirical tunnelling models are important. In addition, these approaches do not address or reproduce convex Arrhenius curves, while the methods discussed in this paper can reproduce and rationalize both the concave and convex Arrhenius plots.

Thus, as there is no unique theory of H-transfer to date, the experimental study of condensed matter model H-transfer systems is important. The scope of this contribution is, therefore, to provide an overview of H-transfer model systems, where the rate constants and kinetic H/D isotope effects are known in a large temperature range. The Arrhenius curves of these model reactions were recalculated using the empirical Bell–Limbach tunnelling model, which is described and justified in §2. Then, ‘simple’ H-transfers, consisting only of an intrinsic H-transfer step, are discussed. Finally, ‘complex’ processes are reviewed, where pre-equilibria affect the Arrhenius curves. An overview of multiple H-transfer reactions, which have been studied in our laboratory (Klein et al. 2004), will be published elsewhere.

2. H-bond geometries and tunnel model

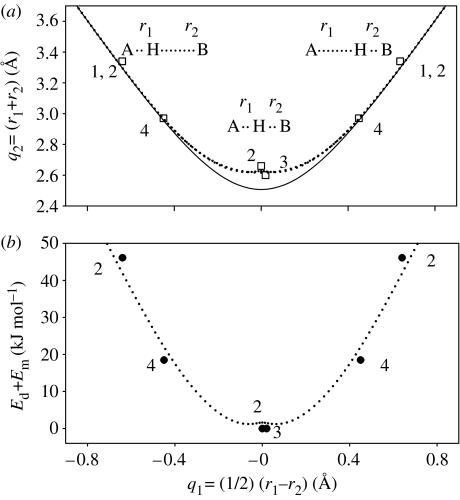

In the past, it has been shown that the neutron diffraction data of hydrogen bonds A–H⋯B indicate a correlation between the two hydrogen bond distances r1≡rA–H and r2≡rH⋯B (Steiner 1995, 1998). One can associate the so-called valence bond orders or bond valences to these distances, which correspond to the ‘exponential distances’:

| (2.1) |

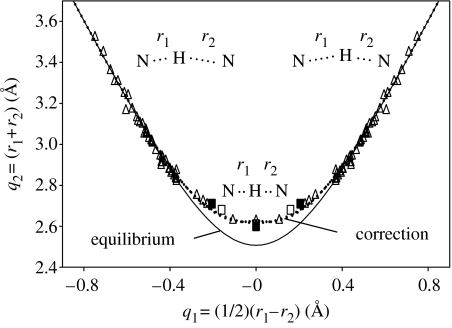

where and represent the equilibrium distances in the free hypothetical diatomic units AH and BH, and b1 and b2 the bond decay parameters. A typical geometric hydrogen-bond correlation is depicted in figure 1 for NHN-hydrogen bonded systems (Limbach et al. 2004b). Here, instead of a plot of r1 versus r2, a plot of q2=r1+r2 versus q1=(1/2)(r1−r2) is shown. For a linear H-bond, q1 represents the distance of H from the H-bond centre and q2 represents the distance between the two heavy atoms of the hydrogen bond. However, the hydrogen-bond angle does not enter the correlation, which is, therefore, valid for both linear as well as nonlinear hydrogen bonds. When H is transferred from one heavy atom to the other, q1 increases from negative to positive values and q2 goes through a minimum, which is located at q1=0 for hydrogen-bonded systems of the AHA-type and near 0 for the AHB-type. The parameters of equation (2.1) are determined by comparison with experimental neutron structures in the Cambridge Structural Data Bank. This correlation means that, in approximation, both proton transfer and hydrogen-bonding coordinates can be combined into a single coordinate. The shortest possible heavy atom distance is given by (Steiner 1998)

which leads to the values of symmetric hydrogen bonds listed in table 1.

Figure 1.

Correlation of the hydrogen-bond length q2=r1+r2 with the proton transfer coordinate q1=(1/2)(r1−r2). The solid line represents the correlation for equilibrium distances calculated with b1=b2=0.404 Å and . The dotted line represents the empirical correction for zero-point vibrations. Open symbols represent the geometries of various NHN-hydrogen bonded systems obtained from neutron structures (open triangles) and solid state NMR data (open squares). Filled squares represent NDN hydrogen bonded systems studied by solid state NMR. Adapted from Limbach et al. (2004b).

Table 1.

Shortest possible heavy atom distances of symmetric H-bonds predicted by the valence bond order model.

| ro (Å) | b (Å) | q2min (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OHO | 0.95 | 0.37 | 2.41 |

| NHN | 0.99 | 0.404 | 2.53 |

| CHC | 1.1 | ∼0.4 | ∼2.75 |

The solid correlation line in figure 1 is calculated using the parameters of table 1, whereas the dotted line includes an empirical correction for zero-point vibrations of the hydrogen atoms in the bridge. Owing to the higher ZPE of H compared to D, the widths of the zero-point vibrational wave functions are also larger. This increases the heavy atom distance q2min, when compared to the equilibrium values of table 1 (Limbach et al. 2005a).

How do the H-bond geometries change during a typical H-transfer process? It is clear that at the minimum value of the heavy atom coordinate q2, only a single geometry is allowed, which is consistent with a single-well potential for the H-motion. In contrast, at other geometries, the correlation curve indicates the possibility of double-well situations, where the barrier height Ed increases with increasing value of the heavy atom coordinate q2.

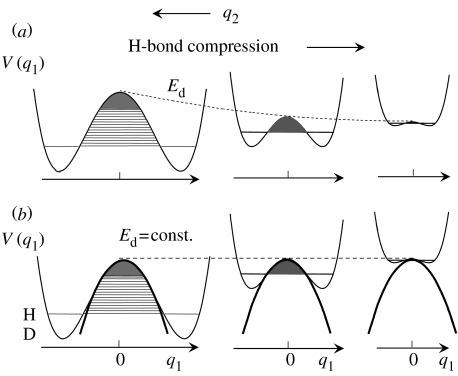

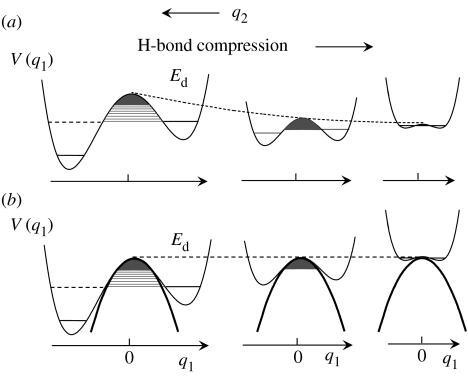

This situation is schematically illustrated in figure 2a in the case of degenerate H-transfers. One-dimensional cuts V(q1) at different values of q2 through a two-dimensional potential surface of a degenerate H-transfer are displayed. The barrier height Ed of the double well, describing the H-transfer, decreases when q2 is decreased, and eventually a single-well configuration is reached. There are only a small number of AH vibrational states below the barrier available; here, only the vibrational ground states are depicted.

Figure 2.

(a) One-dimensional cuts V(q1) through a two-dimensional potential energy surface of a degenerate H-transfer at different values of q2. (b) Reduction of the two-dimensional double-well potential problem to a one-dimensional Bell model. Adapted from Gerritzen & Limbach (1984).

Such a two-dimensional model can be reduced to a one-dimensional model by setting Ed equal to constant as indicated in figure 2b, and by assuming a continuous distribution of configurations with different values of q2. Such a situation can be achieved by the excitation of low-frequency H-bond vibrations or phonons. The situation of figure 2b can be practically replaced by an inverted parabola as a barrier, with a continuous distribution of vibrational levels on both sides of the barrier.

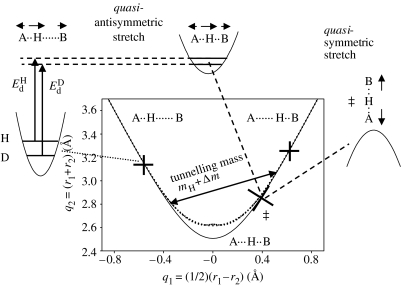

A similar argument holds for non-degenerate H-transfers as illustrated schematically in figure 3. Here, we note that the asymmetry of the potential curve, i.e. the difference in the energy between the two wells, will disappear in the region of the strongest H-bond compression.

Figure 3.

(a) One-dimensional cuts V(q1) through a two-dimensional potential energy surface of a non-degenerate H-transfer at different values of q2. (b) Reduction of the two-dimensional double-well potential problem to a one-dimensional Bell model.

A detailed discussion of the origin of kinetic H/D isotope effects is beyond the scope of this paper. However, we note two sources that have been discussed in §1, i.e. (i) ZPE changes of H in the TS as compared to the initial state; and (ii) tunnel effects leading to KIEs because of different tunnelling masses for H and D.

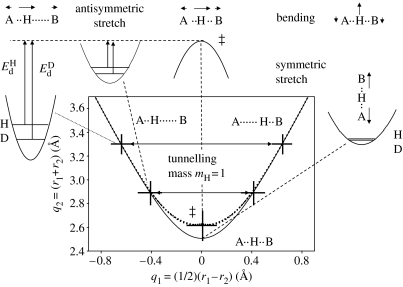

The expected changes in the ZPEs of the H-transfer for a degenerate reaction are illustrated schematically in figure 4. The antisymmetric stretch in the initial state exhibits different ZPEs for H and D as the force constants are large. This vibration becomes imaginary in the TS, which is assumed to be located in the minimum of q2 and the associated ZPE is lost. There is ZPE in the bending vibration, but little ZPE in the symmetric stretch in the TS. This leads to a substantial difference in the effective barriers of the H- and D-transfers. Tunnelling pathways can occur at larger values of q2, which is expected to remain constant during the tunnelling process. Then, the tunnelling mass is 1 for H and 2 for D.

Figure 4.

Hydrogen-bond correlation and zero-point vibrations of a degenerate H-transfer. The transition state is indicated by the double dagger. It is characterized by an imaginary frequency corresponding to a saddle point.

In contrast, if the transfer is non-degenerate, then a situation may occur as indicated in figure 5. At the TS, there is remaining ZPE in the antisymmetric stretch. This will lead to a decrease in the difference of the effective barriers for H and D. Tunnelling pathways may no longer involve only changes of q1, but a substantial heavy atom motion. This means that the effective tunnelling masses will be increased by an additional mass Δm as illustrated schematically in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Hydrogen-bond correlation and zero-point vibrations of a non-degenerate H-transfer.

The simplest tunnel model that allows one to calculate Arrhenius curves of H-transfer reactions is the Bell tunnelling model (Bell 1973), which has been modified in our laboratory (Gerritzen & Limbach 1984). The model has been reviewed recently by Limbach & Klein et al. (2004a).

The probability of a particle passing through or crossing a barrier is given by Bell (1973, 1980)

| (2.3) |

where W represents the energy of the particle and D(W) the transmission coefficient given according to the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin approximation by

| (2.4) |

where pi represents the momentum; m, the mass of the particle moving in the x-direction; V(x), the potential energy experienced by the particle; a′, the position of the particle when it enters or leaves the barrier region; V(0)=Ed, the energy of the barrier, i.e. the ‘barrier height’; and 2a, the width of the barrier at the lowest energy, where tunnelling can occur. Classically, G(W)=0 for W<Ed and G(W)=1 for W>Ed, but quantum-mechanically G(W)>0 for W≤Ed and G(W)<1 for W≥Ed. We assume that the barrier region can be approximated by an inverted barrier, i.e. the potential is given by

| (2.5) |

It has been shown by Bell (1973, p. 275) that

| (2.6) |

where νt represents the ‘tunnel frequency’. The fraction of particles in the energy interval dW is given by the Boltzmann law

| (2.7) |

The classical integrated reaction probability is then given by

| (2.8) |

the quantum-mechanical integrated reaction probability by

| (2.9) |

and the ratio of both quantities by

| (2.10) |

Using an Arrhenius-type law for the classical temperature dependence, it follows that

| (2.11) |

Replacing the Boltzmann constant by the gas constant, and introducing a superscript as label for the isotope L=H, D, it follows that

| (2.12) |

At very high temperatures, the integral becomes unity and one obtains the classical expression

From equation (2.12), one obtains the following expression for the ‘primary’ kinetic H/D isotope effect as a function of temperature:

where QL is the ‘tunnel correction’ (Bell 1973). The energy difference describing the losses of ZPE between the reactant and the TS can be calculated using Bigeleisen theory (Bigeleisen 1949, 1955).

In the low temperature regime for W=0, it follows from equation (2.6) that

| (2.15) |

Therefore,

| (2.16) |

We assume that the width of the barrier for the D-transfer can be calculated from equation (2.5), resulting in

| (2.17) |

With mH=1 and mD=2; the low-temperature rate constant is then determined mainly by aH for a given value of . The low-temperature and temperature-independent KIEs are, therefore, determined by , which is experimentally obtained at high temperatures. In other words, and the high-temperature KIEs cannot be varied independently of each other, which is not in agreement with the experimental data. This effect can be associated with heavy atom tunnelling during the H-transfer. The tunnelling mass increases and the low-temperature H/D isotope effect decreases.

In order to take the heavy atom tunnelling into account, we use the expansion (Gerritzen & Limbach 1984)

| (2.18) |

with

| (2.19) |

The heavy atom contribution generally reduces the value of . For example, if both oxygen atoms are displaced each by 2aO=0.05 Å during H-tunnelling in an OHO-hydrogen bond over 2aH=0.5 Å, then it follows that Δm=0.32, and the total tunnelling mass is 1.32 instead of 1.

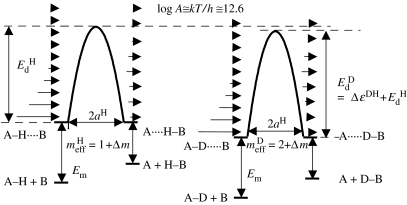

Equation (2.12) is visualized in figure 6. A Boltzmann distribution of particles, where the populations are symbolized by arrows of different length, hits the barrier from the left side. The arrows on the right side represent the particles that tunnelled through the barrier. As the tunnelling mass of H is smaller than D, at a given temperature, the energy for the maximum number of H tunnelling through the barrier is smaller than for D.

Figure 6.

Modified Bell tunnelling model for H- and D-transfer. Adapted from Limbach & Klein et al. (2004a).

As has been proposed by Gerritzen & Limbach (1984), equation (2.12) needs to be modified in a minor way for application in multiple proton transfer reactions. The most important change is to replace the lower integration limit of 0 in equation (2.11) by a minimum energy Em for tunnelling to occur, as illustrated in figure 6, i.e.

| (2.20) |

This modification is necessary, for example, when the reaction pathway involves an intermediate. Tunnelling can then take place only at an energy which corresponds to the energy of the intermediate. Then, one can identify Em with the energy Ei of this intermediate. However, Em may also represent or include an energy Er necessary for a heavy atom rearrangement preceding the tunnelling process. In this interpretation, it also represents the ‘work term’ in the Marcus theory of electron transfer (Marcus 1966). A set of Arrhenius curves, calculated using equation (2.20), then depend on the following parameters:

A single pre-exponential factor A in s−1 is used for all isotopic reactions, i.e. a possible mass dependence is neglected within the margin of error. If solvent reorganization and pre-equilibria are absent, A is expected to be about 1013 s−1. According to TST, pre-exponential factors are given by kT/h=1012.6 s−1 for T=298 K.

Em=ΔH+Er+Ei represents the minimum energy for tunnelling to occur as described earlier and is assumed to be isotope-independent. We note that a similar effect on the Arrhenius curves may be obtained by using more complex barrier shapes (Basran et al. 2001). Several terms may contribute to Em. Er represents a reorganization energy arising from heavy atom motions preceding the H-transfer. Ei represents an energy gap or energy asymmetry between the initial state and the final state. ΔH represents the reaction enthalpy of any pre-equilibrium of H-transfer discussed earlier. ΔH is most often assumed to be isotope-independent, and leads, therefore, to temperature-independent KIEs as has been discussed in both enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems (Kwart 1982; Gerritzen et al. 1984; Braun et al. 1994; Limbach & Klein et al. 2004a; Kohen 2006). Such non-zero enthalpy has been used in many cases as the main evidence for systems that can only be rationalized by ‘Marcus-like’ models (Kohen & Klinman 1999; Basran et al. 2006).

is the barrier height for the H-transfer step of interest. Therefore, the sum represents the total barrier height for the H-transfer.

2aH is the barrier width of the inverted parabola used to describe the barrier of the H-transfer at energy Em. This parameter indicates the tunnel distance of H. 2aD is not much different and is given by equation (2.17).

represents the increase in the barrier height when H is replaced by D.

The tunnelling masses are given by , L=H, D with and . Δm corresponds to the contribution of heavy atom displacements during the tunnelling process as defined in equation (2.19).

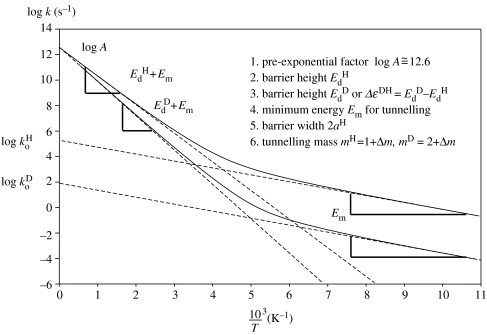

In order to illustrate the formalism, we have plotted typical Arrhenius curves of H- and D-transfer reactions using arbitrary parameters in figure 7. From the slopes of the two curves, at high temperature quantities and can be obtained. Different slopes lead to temperature-dependent kinetic H/D isotope effects in this temperature range. At low temperature, parallel Arrhenius curves are expected, exhibiting a slope given by Em. By extrapolation of the low-temperature branches to high temperatures, the values of and are obtained. According to equation (2.16), they provide information about the barrier width, 2aH, and the heavy atom tunnelling extra mass, Δm.

Figure 7.

Arrhenius curves of H- and D-transfer calculated according to the Bell–Limbach tunnelling model, illustrating the parameters of the model.

All the parameters of the Arrhenius curves discussed in the following sections are listed in table 2. In the cases of complex H-transfers, which involve pre-equilibria, the reaction enthalpies (ΔH) and reaction entropies (ΔS) of the pre-equilibria are also included. A unique parameter set can, however, be obtained only if the kinetic data of the H- and D-reactions are available in both the low- as well as the high-temperature regime. This is not always the case.

Table 2.

Bell–Limbach tunnelling model parameters of various H-transfers.

| r1 (Å) | r2 (Å) | (kH/kD)298 K | Em (kJ mol−1) | ΔH (kJ mol−1) | ΔS (J K−1 mol−1) | log A (s−1) | Ed (kJ mol−1) | Δm (a.m.u.) | 2a (Å) | Δϵ (kJ mol−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| porphyrina | 1.03b/1.32d | 2.31b/1.28d | 11.5 | 23.4 | — | — | 12.6 | 29.3 | 2.5 [1.5] | 0.48 [0.68] | HD 4.9 [4.95], DT 3.0 [2.2] |

| porphyrin aniona | 1.03b/1.33e | 2.31b/1.33f | 16.5 | 10.7 | — | — | 12.6 | 35.4 | 0 [1.5] | 0.87 [0.78] | HD 6.5 [7.74], DT 4.2 [3.8] |

| TTAAg | 1.03 | 1.94 | 1.8 | 3.4 [2.9] | — | — | 12.6 [12.4] | 15.1 [14.2] | 3 [3] | 0.17 [0.50] | 1.05 [3.0] |

| MeBOh | — | — | 14.5 | 0.293 | −9 | −60 | 12.6 | 19.7 | 2.1 | 0.29 | 5.44 |

| Ingold radicali | — | — | 18 | 4.2 | −18 | −98 | 12.6 | 49.4 | 1.8 | 0.39 | 5.86 |

| bsADH enzymec state 1 | — | — | 41.8 | — | — | 12.6 | 48.1 | 0 | 0.36 | 5.86 | |

| bsADH enzymec state 2 | — | — | 4.8 | 55.7 | 100j | 333j | 12.6 | 33.5 | 0 | 0.14 | 0 |

| Loth radicale | — | — | 56 | 0 | 21 | 38 | 12.6 | 27.2 | 0 | 0.3 | 6.7 |

| Bubnov radicalk | — | — | 9.8 | 1.26 | — | — | 12.6 | 23.9 | 1 | 0.17 | 3.3 |

Transition state values calculated by Maity et al. (2000).

Transition state values calculated by Vangberg & Ghosh (1997).

Reaction enthalpy and entropy of the formation of state 2 dominating at high temperatures from state 1 dominating at low temperatures. Square brackets indicate values published previously.

3. Elementary single H-transfers

In this section, we will discuss the Arrhenius curves of three single H-transfers where the rate constants observed refer to a well-defined elementary reaction step.

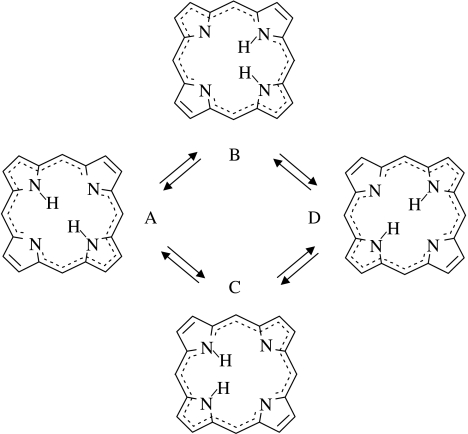

As a first example, we discuss the tautomerism of unsubstituted porphyrin (scheme 1). This molecule forms two degenerate trans-tautomers A and D, which interconvert by two successive non-degenerate single proton transfer steps via the degenerate cis-intermediates B and C. It has been shown (Limbach et al. 1982) using formal kinetics that the observed rate constants of the overall process are given by

| (3.1) |

where the rate constant kLL refers to the degenerate double hydron transfer from A to D, and the rate constant kL to the uphill single hydron transfer rate constants from A to B or C. Experimentally, the rate constants kHH, kHD and kDD were measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in the liquid and the solid state (Braun et al. 1994). The values of kHH and kDD were reported by Butenhoff & Moore (1988). Later, the values of kHT and kTT could also be measured by dynamic NMR spectroscopy (Braun et al. 1996a). In these papers, the validity of equation (3.1) was checked, which experimentally proved the stepwise transfer. Thus, the rate constant kL, L=H, D and T could be measured. In a subsequent paper, the corresponding rate constants of the mono-deprotonated porphyrin anion were also measured for liquid solution and a solid phosphazene matrix (Braun et al. 1996b). Again, no dependence of the rate constants on the environment was observed.

Scheme 1.

The tautomerism of unsubstituted porphyrin.

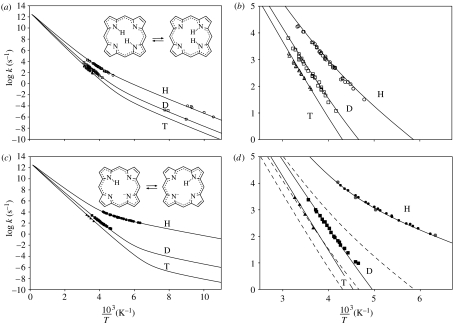

All the rate constants measured for both the systems are depicted in the Arrhenius diagrams in figure 8. For the parent compound porphyrin, an Arrhenius curve pattern as discussed in figure 7 is observed. Noteworthy is the same slope Em of the Arrhenius curves of the H- and D-transfer leading to temperature-independent isotope effects at low temperatures. As illustrated schematically in figure 9, Em will be caused by the asymmetry of the reaction to a greater part. It is clear that not only the energy of the cis-intermediate is required for tunnelling to occur, but also some reorganization energy of the ring skeleton might be necessary. We also note that the low-temperature kinetic H/D isotope effect is smaller than that predicted from the relatively large barrier difference of H and D evaluated at high temperatures. In order to match this, a relatively high value of Δm for heavy atom contribution had to be used to reduce the low-temperature isotope effect. We note that Smedarchina et al. (1998) have reproduced the Arrhenius curves of all isotopic reactions of porphyrin using the same theory.

Figure 8.

Arrhenius diagrams of the tautomerism of (a, b) porphyrin and its (c, d) mono-deprotonated anion. Adapted from Braun et al. (1996b). The solid lines were calculated using the parameters listed in table 2.

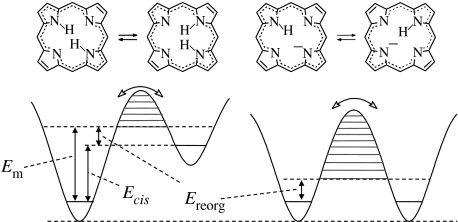

Figure 9.

Potential curves (schematically) of the tautomerism of porphyrin and its mono-deprotonated anion. Adapted from Braun et al. (1996b).

In contrast, this was not necessary in the case of the porphyrin anion, where the transfer is degenerate and the low-temperature KIEs are substantially larger than in the parent compound. Therefore, we assign a much smaller value of Em to the reorganization of the porphyrin skeleton preceding the transfer. When compared to the parent compound, larger values for both the tunnelling distance as well as for the differences of the barrier heights of the isotopic reactions are obtained. These findings can be associated with the lack of reaction asymmetry in the anion as discussed in §2.

The porphyrin analogue 1,8-dihydro-5,7,12,14-tetramethyldibenzo(b,i)-15N4-(1,4,8,11)-tetraazacyclotetra-deca-4,6,11,13-tetraene (TTAA) (figure 10) is subject to a related stepwise tautomerism in the crystalline state (Langer et al. 2001), which was studied by solid-state NMR and NMR relaxometry (Hoelger et al. 1994) in the microsecond time-scale. Here, we discuss only the transfer step illustrated in figure 10. Evidence was found that the transfer is near-degenerate. Concave Arrhenius curves for the H- and D-reactions were observed in a large temperature range, exhibiting surprisingly small kinetic H/D isotope effects, which were explained in terms of a relatively large heavy atom contribution to tunnelling and a small barrier width. The latter could arise from the substantially stronger H-bond in TTAA compared to the porphyrin.

Figure 10.

Arrhenius diagrams of the tautomerism of polycrystalline 1,8-dihydro-5,7,12,14-tetramethyldibenzo(b,i)-15N4-(1,4,8,11)-tetraazacyclotetra-deca-4,6,11,13-tetraene (TTAA) according to Langer et al. (2001). The solid lines were calculated using the parameters listed in table 2.

In figure 11a, we have plotted the values of the correlated hydrogen-bond coordinates of porphyrin, TTAA (table 2), as well as the calculated values of the TSs of porphyrin (Maity et al. 2000) and of its anion (Vangberg & Ghosh 1997). We note that all geometries are located on the NHN-hydrogen bond correlation curve of figure 1, especially the coordinates of the TSs of porphyrin and its anion, exhibiting values of 2.60 and 2.66 Å. This means that hydrogen-bond compression of porphyrin is the most important heavy atom motion, which enables the tautomerism; the TS structures correspond to the expected strongest possible NHN-hydrogen bonds, whereas the initial states do not show any sign of hydrogen-bonding.

Figure 11.

(a) Hydrogen-bond geometries of (1) porphyrin, (3) its transition state, (2) the transition state of the porphyrin anion and (4) polycrystalline 1,8-dihydro-5,7,12,14-tetramethyldibenzo(b,i)-15N4-(1,4,8,11)-tetraazacyclotetra-deca-4,6,11,13-tetraene (TTAA). Values were taken from table 2. (b) Barrier heights of the H-transfer are calculated from the Arrhenius curves of the species in (a). The barrier heights of the transition states are set to zero.

The question arises of how the intrinsic barrier of the symmetric H-transfer depends on the hydrogen-bond geometries. In figure 11b we have therefore plotted the experimental values of Ed+Em for the porphyrin anion and TTAA as a function of q1 (table 2). We included the values of zero as a reference for the TSs calculated for porphyrin (Maity et al. 2000) and the anion (Vangberg & Ghosh 1997). The dotted line seems to represent the observed data well and was calculated using

We do not expect this relation to be of general use, as electronic effects are not taken into account. However, it would be interesting to know in the future how well the geometries of initial and TSs can be described in terms of the bond-valence concept.

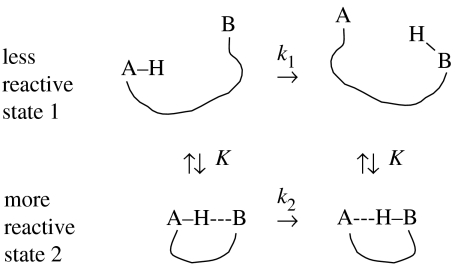

4. Complex H-transfers

In many H-transfer reactions in solution, with the exception of intramolecular reactions as in porphyrins, the reaction centres first have to form a reactive complex from non-reactive configurations. In this section, we will study the question how Arrhenius curves are affected by pre-equilibria, and then discuss various experimentally published cases.

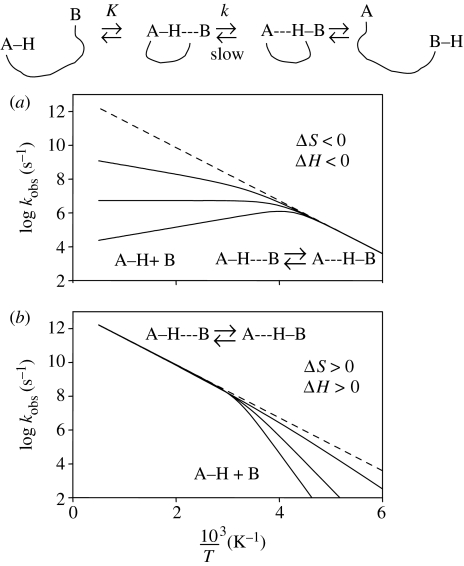

(a) The effects of a fast pre-equilibrium on the observed rates of H-transfer

We treat the following reaction:

| (4.1) |

where NR stands for non-reactive reactants, R for reactive reactants and P for the products. This model is intentionally very simple and for complex systems such as enzymes, NR and R represent two ensembles of non-reactive and reactive states. This model and its ability to explain curved Arrhenius plots are in accordance with the more general Tolman's interpretation of the activation energy (Truhlar & Kohen 2001). The following description is simplified by assuming that the pre-equilibrium is fast, and the isotope-sensitive H-transfer converting the reactive forms into products constitutes the rate-limiting step. This assumption can be omitted with minor effect on the structure of the following equations. Practically, the important property of K is that isotopically it is not sensitive, while k is sensitive. The equilibrium constant of the pre-equilibrium (K) is given by

| (4.2) |

where ΔH and ΔS represent the enthalpy and entropy of the pre-equilibrium. k represents the first-order or pseudo-first-order rate constant of the rate-limiting H-transfer which converts the reactants to the products. Please note that this H-transfer process (k) includes all the isotopically sensitive steps that lead to the formation of the tunnelling configuration and any motion that is coupled to the H-transfer between the donor and the acceptor. Since tunnelling per se occurs only between degenerated energy levels, all the asymmetric curves in the current model (e.g. figure 3) require vibrational excitation (motion) prior to tunnelling, and that motion is included in k. A model by Klinman is presented in this issue (Klinman 2006), where the terms ‘coarse tuning’ and ‘fine tuning’ are coined to describe different stages of system pre-arrangement toward tunnelling conformation. This model is a good analogy to the one described here despite the fact that in Klinman's model, the fine tuning is on a faster time-scale than the coarse one. In the following, the rate expression for the observed rate constants kobs is depicted.

With the total concentration C=cNR+cR it follows that

| (4.3) |

Often, only the sum of the concentrations of NR and R is measured, i.e. the kinetics cannot distinguish between NR and R. As the interconversion between NR and R is assumed to be fast, the observed first-order or pseudo-first-order rate constant is then given by

| (4.4) |

In the case where K≫1, it follows that

| (4.5) |

In contrast, if K≪1, it follows that

| (4.6) |

Let us assume an Arrhenius law for the main reaction step of

| (4.7) |

with arbitrary parameters A=1013 s−1 and Ea=30 kJ mol−1 represented by the dashed line in figure 12. In figure 12a we discuss the case where the formation of the reactive state involves a negative enthalpy and entropy as expected for a hydrogen-bond association between the reaction partners AH and B. Thus, the reacting state predominates at low temperatures, where kobs=k. The true Arrhenius curve is then measured exhibiting normal pre-exponential factors. At high temperatures, however, the reactive state dissociates and becomes non-reactive and kobs=kK. As K≪1 in this region, the observed Arrhenius curve is convex and exhibits an unusually small pre-exponential factor. The effective activation energy is given by Ea−|ΔH|.

Figure 12.

Arrhenius curves of a H-transfer in the presence of a pre-equilibrium. Arbitrary parameters of the Arrhenius curves in the reactive complex: log A=13, and Ea=30 kJ mol−1. Parameters of the formation of the active complex. (a) ΔH=−20 kJ mol−1, ΔS=−70 J K−1 mol−1; ΔH=−30 kJ mol−1, ΔS=−120 J K−1 mol−1; ΔH=−40 kJ mol−1, ΔS=−170 J K−1 mol−1. (b) ΔH=10 kJ mol−1, ΔS=40 J K−1 mol−1; ΔH=30 kJ mol−1, ΔS=100 J K−1 mol−1; ΔH=50 kJ mol−1, ΔS=160 J K−1 mol−1. Adapted from Limbach et al. (2005b).

In figure 12b, we consider a case where the formation of the reactive state involves positive entropy and enthalpy. Such a case could happen if the reaction partners AH and B are involved in strong interactions with other species. For example, AH could be hydrogen-bonded to any proton acceptor, or B to any proton donor, which requires break up of this interaction before the partners can react. The reacting state predominates at high temperatures and the non-reactive state at low temperatures. Only at high temperatures is the true Arrhenius curve measured, exhibiting a normal pre-exponential factor of about 13. At low temperatures, the observed rate constants are smaller than the intrinsic ones; the effective activation energy is given by Ea+|ΔH|. In addition, the observed pre-exponential factor is unusually large.

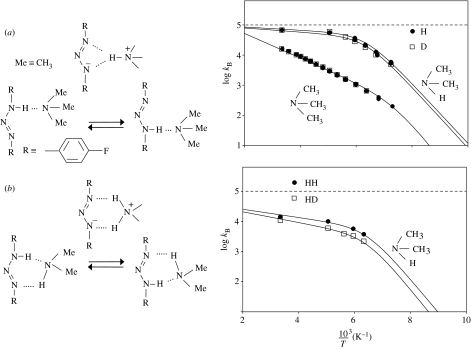

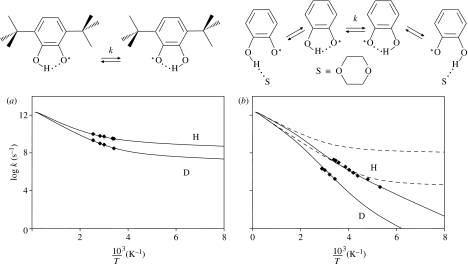

(b) H-transfers with reactive complexes dominating at low temperatures

Let us consider the case of degenerate base-catalysed intra- and intermolecular proton transfer of a triazene as a recent example, which has been discovered (Männle & Limbach 1996) and studied (Limbach et al. 2005b) using dynamic liquid-state NMR (figure 13). In contrast to carboxylic acids and amidines, triazenes cannot form cyclic dimers in which a double proton transfer takes place. 1,3-Bis(4-fluorophenyl)[1,3-15N2]triazene was studied using 1H and 19F NMR in the presence and absence of dimethylamine, trimethylamine and water, using tetrahydrofuran-d8 and methylethylether-d8 as solvents, down to 130 K. Surprisingly, both dimethylamine and trimethylamine were able to pick up the mobile proton of the triazene at one nitrogen atom and carry it to the other nitrogen atom, resulting in an intramolecular transfer process catalysed by a different base molecule each time. Even more surprising is that the intramolecular transfer (figure 13a) catalysed by dimethylamine is faster than the superimposed intermolecular double proton transfer (figure 13b).

Figure 13.

(a) Arrhenius diagrams of the intramolecular proton and deuteron transfer in 1,3-bis-(4-fluorophenyl)-[1,3-15N2]triazene dissolved at a concentration of 0.1 mol l−1 in methylethylether-d8, catalysed by the bases dimethylamine (0.0028 and 0.0041 mol l−1 at xD=0 and 0.95, respectively) and trimethylamine (0.02 mol l−1 at xD=0 and 0.96). kB represents the average inverse lifetimes of the base B between two exchange events. (b) Arrhenius diagrams of the intermolecular proton and deuteron transfer of 1,3-bis-(4-fluorophenyl)-[1,3-15N2]triazene catalysed by dimethylamine. Adapted from Limbach et al. (2005b).

The kinetic H/D isotope effects are small, especially in the catalysis by trimethylamine, indicating a major heavy atom rearrangement and absence of tunnelling. This is because of the high asymmetry of the H-transfer from the triazene to the base. Semi-empirical parametric model 3 (PM3) and ab initio density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate a reaction pathway via a hydrogen-bond switch of the protonated amine representing the TS, where the imaginary frequency required by the saddle point corresponds to a heavy atom motion as was illustrated schematically in figure 4. Tunnelling is absent because of the very high tunnelling masses involved, corresponding to the mass of the base.

The Arrhenius curves of all processes are strongly convex. This phenomenon is explained in terms of the hydrogen-bond association of the triazene with the added bases, preceding the proton transfer. At low temperatures, all catalysts are in a hydrogen-bonded reactive complex with the triazene, and the rate constants observed are equal to the reacting complex. However, at high temperatures, dissociation of the complex occurs, and the temperature dependence of the observed rate constants is also affected by the enthalpy of the hydrogen-bond association according to the intermolecular analogue of equation (4.4). As tunnelling is not involved, we do not discuss the Arrhenius curves in a more quantitative way here. Hence, we refer the reader to the paper by Limbach et al. (2005b).

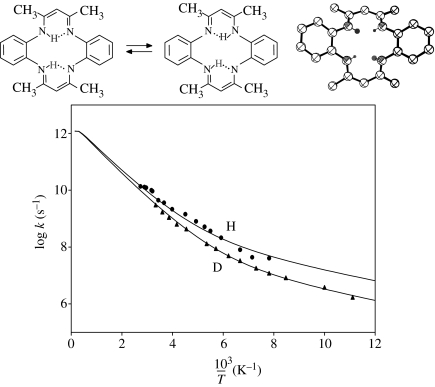

Using optical methods, Al–Soufi et al. (1991) followed the kinetics of the intramolecular H- and D-transfer between the keto and the enol form of 2-(2′-hydroxy-4′-methylphenyl) benzoxazole (MeBO) dissolved in alkanes. No dependence of the rate constants on the solvent viscosity could be found. The Arrhenius diagram obtained in a very wide temperature range is depicted in figure 14. At low temperatures, the rare regime of temperature-independent rate constants is obtained, exhibiting a very large temperature-independent kinetic H/D isotope effect of about 1400. At room temperature, quite a large effect of about 14.5 is still obtained.

Figure 14.

Arrhenius plot of the triplet state tautomerism of 2-(2′-hydroxy-4′-methylphenyl) benzoxazole (MeBO, upper curve) and its deuterated analogue (lower curve) dissolved in alkanes. The kinetic data were taken from Al-Soufi et al. (1991). The solid lines were calculated using the parameters listed in table 2.

A puzzling result in figure 14 was that the experimental pre-exponential factors were only about 109 s−1 instead of about 1013 s−1 as expected, as had been pointed out by the authors of this study. We have recalculated the Arrhenius curves using equation (4.4) and the parameters listed in table 2 are plotted in figure 14. Owing to the large body of data, all parameters could be determined. The calculated intrinsic Arrhenius curves are symbolized by the dashed lines and calculated curves representing the observed rate constants by the solid lines. For their calculation, a pre-equilibrium is assumed where the reactive forms of the molecule dominate at low temperatures. In this region, the intrinsic Arrhenius curves of the H- and the D-transfer symbolized by the dashed lines coincide with the observed ones, as kobs=k. However, at high temperature it is assumed that a non-reactive form of the molecule dominates because of its more positive entropy leading to kobs=kK. Thus, both the observed rate constants and the observed pre-exponential factors are smaller than expected.

We note that a very small minimum energy Em was found for tunnelling to occur at low temperatures, which refers to the reactive complex. This value could, therefore, be determined independently of ΔH and ΔS of the pre-equilibrium. In other cases, as discussed later, only the sum of ΔH+Em can be determined. The barrier for the transfer is similar to the one found for TTAA.

The difference in the barrier for H and D is substantially large, of the order of the one found for porphyrin. In addition, a contribution for heavy atom tunnelling is observed.

At present, we can only speculate about the structure of the non-reactive form. At low temperatures, the keto form may exhibit a zwitterionic aromatic character, and at high temperature a less polar quinoid structure. Both structures are normally limiting structures. However, the zwitterionic structure is highly solvated and will exhibit, therefore, a much more negative entropy compared with the quinoid structure. The entropy decrease is expected to be large especially in the case of apolar, but polarizable solvents as has been shown by Caldin et al. (1975). Another possibility could be the formation of an enolic conformer exhibiting a non-reactive intramolecular OHO- instead of a reactive OHN-hydrogen bond. However, further spectroscopic and kinetic measurements will be necessary to clarify this problem.

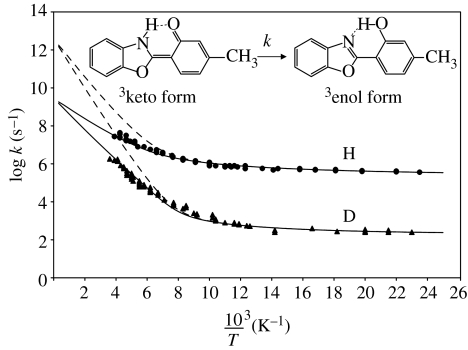

Finally, let us discuss the well-established example of the isomerization of 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylphenyl radical to 3,5-di-tert-butylneophyl in apolar organic solvents depicted in figure 15, which has been studied by Brunton et al. (1978). Various barrier types were used for Bell-type semi-classical tunnelling calculations. It was shown that an inverted parabola could not give a satisfactory fit. The pre-exponential factors found for other barrier types were of the order of 8–12. As depicted in figure 15, a solution to the problem can again be obtained in terms of a pre-equilibrium, where a reactive form again dominates at low temperature and a non-reactive form at high temperature, as in the preceding case of MeBO. In the case of the 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylphenyl radical, one may interpret the reactive form with a configuration where the C–H bonds of the methyl groups are pointing in the direction of the aromatic acceptor carbon atom. Such a configuration could have a more negative entropy compared with the non-reactive forms, with unfavourable transfer geometries dominating at high temperatures. The tunnel parameters used to calculate the Arrhenius curves are included in table 1. No anomaly can be detected; the high barrier can be explained by the limited capability to form CHC-hydrogen bonds.

Figure 15.

Arrhenius curves of the isomerization of the 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylphenyl radical to 3,5-di-tert-butylneophyl in apolar organic solvents. The solid and dashed lines were calculated as described in the text using the parameters listed in table 2. Data from Brunton et al. (1978).

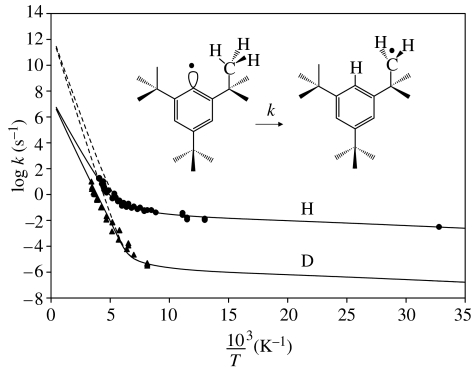

(c) H-transfers with reacting complexes dominating at high temperatures

Let us discuss some examples where non-reactive states are present at low temperatures and reactive states at high temperatures.

The first two examples are the H-transfers in 2-hydroxyphenoxyl radicals, which have been studied using dynamic electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. When 3,6-di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxyphenoxyl and its deuterated analogue are dissolved in heptane, the Arrhenius diagram of figure 16a is obtained (Bubnov et al. 1978). The KIE is about 10 at room temperature. Setting the pre-exponential factor to 1012.6 (table 2), leads to the concave Arrhenius curve depicted as solid lines. In contrast, figure 16b depicts the kinetic data of the parent compound 2-hydroxyphenoxyl in CCl4/CCl3F to which 0.11 mol l−1 dioxane had been added to increase the solubility. Now, a KIE of about 56 is obtained at room temperature. This large difference between the two molecules was noted some time ago by Limbach & Gerritzen (1982); in particular, that the effective frequency factor of the D-transfer was substantially smaller than that of the H- transfer. Two Arrhenius curves of the H- and D-reactions are almost parallel. Application of Bell–Limbach tunnelling leads to unusually large pre-exponential factors of 1018 s−1. As shown in figure 16b and the parameters in table 2, the use of equation (4.4) improves the analysis, although the interpretation is similar as before.

Figure 16.

(a) Arrhenius curves of the tautomerism of 3,6-di-tert-butyl-2-hydroxyphenoxyl dissolved in heptane according to Bubnov et al. (1978). (b) 2-Hydroxyphenoxyl dissolved in CCl4/CCl3F/dioxane according to Loth et al. (1976). The solid lines were calculated using the parameters listed in table 2.

The dashed lines in figure 16b indicate the intrinsic Arrhenius curves of the transfer, whereas the solid lines indicate the one including the pre-equilibrium. The reduction in the rate constants compared to the di-tert-butyl radical is explained by the formation of a non-reactive species at low temperatures, which is hydrogen-bonded to the added dioxane. Thus, for the reaction to occur, first the intramolecular H-bonded species has to be formed, which exhibits not only a higher energy but also a more positive entropy. A comparison of the Arrhenius curves in figure 16b indicates that the desolvated intramolecular H-bonded species is never dominant over the whole temperature range, as the interaction with dioxane is stronger because of the linear intermolecular H-bond, in comparison with the weaker intramolecular H-bond.

The larger kinetic H/D isotope effects in the parent radical can be explained in terms of its higher symmetry compared with the di-tert-butyl radical. In the latter, the methyl groups on both sides of the ring are not ordered, leading to the effective asymmetric double-well of the H-transfer potentials.

These examples show how subtle structural effects can lead to very different H-transfer properties.

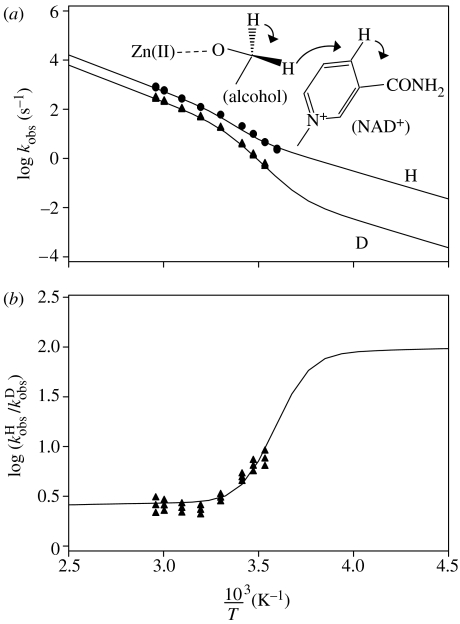

(d) H-transfer with different reacting complexes at different temperatures

Finally, let us discuss the example of a thermophilic alcohol dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus (bsADH) studied by Kohen et al. (1999). This enzyme catalyses the abstraction of a hydride to NAD+ as depicted in figure 17. The Arrhenius diagram is depicted in figure 17a; a sudden decrease in the apparent slope and intercept of the Arrhenius curves is observed around room temperature. The puzzling observation is that the KIEs are temperature-independent in the high-temperature regime, but temperature-dependent in the low-temperature regime.

Figure 17.

(a) Arrhenius curves of the intrinsic H-transfer in a thermophilic alcohol dehydrogenase (bsADH). The kinetic data are taken from Kohen et al. (1999). (b) Corresponding logarithms of the kinetic H/D isotope effects. The solid lines were calculated using the reaction network of scheme 2 and the parameters listed in table 2.

The solid lines in figure 17a were calculated assuming the simple reaction network of scheme 2. It is assumed that the enzyme adopts two different states 1 and 2 at equilibrium (K), where 1 is less reactive than 2 (scheme 2). In the less-reactive state 1 dominating at lower temperatures, the rate constant of H-transfer is given by k1, but in the more reactive state dominating at higher temperatures, it is given by k2. Assuming again that the H-transfer is slower than the conversions between the states, we obtain the following expression by modification of equation (4.4):

| (4.8) |

where x1 and x2 correspond to the mole fractions of states 1 and 2 and K is again the equilibrium constant of the formation of state 2 from state 1. According to table 2, state 2 dominates at higher temperatures in spite of its higher energy because of its very large positive entropy: this could be a state where the protein has become ideally flexible for proper activity, in contrast to the low-temperature regime. This conclusion is in accordance with the fact that bsADH evolved to function at approximately 65 °C and with qualitative suggestions proposed in the past to rationalize the curved Arrhenius plot (Kohen & Klinman 1999, 2000; Kohen et al. 1999; Liang et al. 2004).

Scheme 2.

Conformational dependent H-transfer in an biomolecule.

The tunnel parameters included in table 2 indicate a groundstate tunnelling situation at high and low temperatures, with temperature-independent KIEs. The apparent temperature dependence observed at low temperatures is the result of the transition between the two regimes, but does not arise from intrinsic temperature-dependent KIEs. We note that in both states the pre-exponential factor of 1012.6 s−1 employed throughout this study was consistent with the data. The minimum energy for tunnelling to occur is larger in the high-temperature state 2, but the barrier height and the barrier width are smaller compared with the low-temperature state 1. Thus, there seems to be a substantial change in the barrier parameters upon flexibilization of the enzyme at higher temperatures.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have analysed the Arrhenius curves of various H- and D-transfer reactions using the Bell–Limbach tunnelling model. In this model, semi-classical tunnelling calculations are performed using the parameters that can be obtained empirically by fitting to the experiment. A main parameter is the pre-exponential factor that is found to be of the order of kT/h≅1012.6 s−1. In the current model, deviations from this value indicate the presence of a pre-equilibrium that is sometimes also manifest in convex-shaped Arrhenius curves. A minimum energy for tunnelling represents the slope of the Arrhenius curves at low temperature in the regime of temperature-independent KIEs. For degenerate H-transfers, the difference in the effective barriers of the H- and D-transfer are larger than the non-degenerate transfers. Contributions from heavy atom tunnelling to the tunnelling masses seem to be larger in the non-degenerate cases. Both effects lead to larger KIEs for the degenerate transfer processes compared with the non-degenerate ones. These conclusions show that the Bell–Limbach tunnel model is useful for the first screening of experimental data. Especially, one becomes conscious of the number and type of parameters that can be obtained from these data. This model is not contradictory to many of the models classified as Marcus-like (for review of such models, see Kohen 2006 and Klinman's contribution to this in this issue). The two concepts overlap at the fact that Δm (2.19) is part of the tunnelling mass (meff). Even though the procedures are very different, the ‘tunnelling’ of the heavy atoms, whose motion is coupled to the H-tunnelling, is analogues to the environmental dynamics that are promoting or at least coupled to the H-tunnelling in Marcus-like models. Thus, the Bell–Limbach model does not replace a more physical description based on quantum-mechanical and rate theories, but helps to prepare for their use, by detecting, for example, a hidden pre-equilibrium. An ideal treatment of experimental data is a ladder of different theoretical treatments, where each treatment consists of an important step towards a better understanding of H-transfer reactions. The current model treats deviations from classical Arrhenius plot in a similar manner to Truhlar & Kohen (2001) by dividing the reacting system into two populations, reactive (R) and non-reactive (NR). The unique advantage of the model presented here over many other more detailed and sophisticated models is the way the temperature dependency of the rate and isotope effect is addressed and its ability to fit and rationalize nonlinear Arrhenius plots. Finally, we note that in the case of thermophilic dehydrogenase, a new kind of temperature-dependent KIEs is proposed, consisting of a transition between two regimes with different temperature-independent KIEs.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn, via the Research Training Center 788 ‘Hydrogen Bonding and Hydrogen Transfer’ and the project Ma 515/20, and NIH (GM065368) and NSF (CHE 01-33117). We also thank the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (Frankfurt) for financial support.

Footnotes

One contribution of 16 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Quantum catalysis in enzymes—beyond the transition state theory paradigm’.

References

- Al-Soufi W, Grellmann K.H, Nickel B. Keto–enol tautomerization of 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole and 2-(2′-hydroxy-4′-methylphenyl)benzoxazole in the triplet state: hydrogen tunneling and isotope effects. 1. Transient absorption kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:10 503–10 509. doi:10.1021/j100178a043 [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou D, Schwartz S.D. Internal enzyme motions as a source of catalytic activity: rate-promoting vibrations and hydrogen tunneling. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:5553–5558. doi:10.1021/jp004547b [Google Scholar]

- Basran J, Patel S, Sutcliffe M.J, Scrutton N.S. Importance of barrier shape in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Vibrationally assisted hydrogen tunneling in tryptophan tryptophylquinone-dependent amine dehydrogenases. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6234–6242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008141200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008141200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basran J, Masgrau L, Sutcliffe M.J, Scrutton N.S. Solution and computational studies of kinetic isotope effects in flavoprotein and quinoprotein catalyzed substrate oxidations as probes of enzymic hydrogen tunneling and mechanism. In: Kohen A, Limbach H.H, editors. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. ch. 25. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 671–690. [Google Scholar]

- Bell R.P. 2nd edn. Chapman & Hall; London, UK: 1973. The proton in chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Bell R.P. Chapman & Hall; London, UK: 1980. The tunnel effect. [Google Scholar]

- Bigeleisen J. The relative reaction velocities of isotopic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1949;17:675–678. doi:10.1063/1.1747368 [Google Scholar]

- Bigeleisen J. Statistical mechanics of isotopic systems with small quantum corrections. I. General considerations and the rule of the geometric mean. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:2264–2267. doi:10.1063/1.1740735 [Google Scholar]

- Brackhagen O, Scheurer Ch, Meyer R, Limbach H.H. Hydrogen transfer in the porphin anion: a quantum dynamical study of vibrational effects. Special Issue on Hydrogen transfer: experiment and theory. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 1998;102:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Braun J, Schlabach M, Wehrle B, Köcher M, Vogel E, Limbach H.H. NMR study of the tautomerism of porphyrin including the kinetic HH/HD/DD isotope effects in the liquid and the solid state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:6593–6604. doi:10.1021/ja00094a014 [Google Scholar]

- Braun J, Limbach H.H, Williams P, Morimoto H, Wemmer D. Observation of kinetic tritium isotope effects by dynamic NMR. Example: the tautomerism of porphyrin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996a;118:7231–7232. doi:10.1021/ja954146n [Google Scholar]

- Braun J, Schwesinger R, Williams P.G, Morimoto H, Wemmer D.E, Limbach H.H. Kinetic H/D/T isotope and solid state effects on the tautomerism of the conjugated porphyrin monoanion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996b;118:11 101–11 110. doi:10.1021/ja961313q [Google Scholar]

- Bruniche-Olsen N, Ulstrup J. Quantum theory of kinetic isotope effects in proton transfer reactions. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1. 1979;75:205–226. doi:10.1039/f19797500205 [Google Scholar]

- Brunton G, Gray J.A, Griller D, Barclay L.R.C, Ingold K.U. Kinetic applications of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. 32. Further studies of quantum-mechanical tunneling in the isomerization of sterically hindered aryl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:4197–4200. doi:10.1021/ja00481a031 [Google Scholar]

- Bubnov N.N, Solodnikov S.P, Prokofiev A.I, Kabachnik M.I. Dynamics of degenerate tautomerism in free radicals. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1978;47:549–571. doi:10.1070/RC1978v047n06ABEH002238 [Google Scholar]

- Butenhoff T.J, Moore C.B. Hydrogen atom tunneling in the thermal tautomerism of porphine imbedded in a n-hexane matrix. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:8336–8341. doi:10.1021/ja00233a009 [Google Scholar]

- Caldin E.F, Mateo S. Kinetic isotope effects and tunnelling in the proton-transfer reaction between 4-nitrophenylnitromethane and tetramethylguanidine in various aprotic solvents. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1. 1975;71:1876–1904. doi:10.1039/f19757101876 [Google Scholar]

- German E.D, Kuznetsov A.M, Dogonadze R.R. Theory of the kinetic isotope effect in proton transfer reactions in a polar medium. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2. 1980;76:1128–1146. doi:10.1039/f29807601128 [Google Scholar]

- Gerritzen D, Limbach H.H. Kinetic isotope effects and tunneling in cyclic double and triple proton transfer between acetic acid and methanol in tetrahydrofuran studied by dynamic 1H and 2H NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:869–879. doi:10.1021/ja00316a007 [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher E, Soudackov A.V, Hammes-Schiffer S. Proton-coupled electron transfer in soybean lipoxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5763–5775. doi: 10.1021/ja039606o. doi:10.1021/ja039606o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelger C.G, Wehrle B, Benedict H, Limbach H.H. High-resolution solid-state NMR relaxometry as a kinetic tool for the study of ultrafast proton transfers in crystalline powders. Example: dimethyldibenzotetraaza[14]annulene. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:843–851. doi:10.1021/j100054a020 [Google Scholar]

- Klein O, Aguilar-Parrilla F, Lopez J.M, Jagerovic N, Elguero J, Limbach H.H. A dynamic NMR study of the mechanisms of double, triple and quadruple proton and deuteron transfer in cyclic hydrogen bonded solids of pyrazole derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11 718–11 732. doi: 10.1021/ja0493650. doi:10.1021/ja0493650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinman J.P. Linking protein structure and dynamics to catalysis: the role of hydrogen tunnelling. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2006;361:1323–1331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1870. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M.J, Rickert K, Klinman J.P. Temperature-dependent isotope effects in soybean lipoxygenase-1: correlating hydrogen tunneling with protein dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3865–3874. doi: 10.1021/ja012205t. doi:10.1021/ja012205t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohen A. Kinetic isotope effects as probes for hydrogen tunneling in enzyme catalysis. In: Kohen A, Limbach H.H, editors. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. ch. 28. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 743–764. [Google Scholar]

- Kohen A, Klinman J.P. Hydrogen tunneling in biology. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:R191–R198. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80058-1. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80058-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohen A, Klinman J.P. Protein flexibility correlates with degree of hydrogen tunneling in thermophilic and mesophilic alcohol dehydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10 738–10 739. doi:10.1021/ja002229k [Google Scholar]

- Kohen A, Cannio R, Bartolucci S, Klinman J.P. Enzyme dynamics and hydrogen tunnelling in a thermophilic alcohol dehydrogenase. Nature. 1999;399:496–499. doi: 10.1038/20981. doi:10.1038/20981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov A.M, Ulstrup J. Proton and hydrogen atom tunnelling in hydrolytic and redox enzyme catalysis. Can. J. Chem. 1999;77:1085–1096. doi:10.1139/cjc-77-5-6-1085 [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov A.M, Ulstrup J. Proton transfer and proton conductivity in condensed matter environment. In: Kohen A, Limbach H.H, editors. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. ch. 26. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 691–724. [Google Scholar]

- Kwart H. Temperature dependence of primary kinetic isotope effect as a mechanistic criterion. Acc. Chem. Res. 1982;15:401–408. doi:10.1021/ar00084a004 [Google Scholar]

- Langer U, Hoelger C, Wehrle B, Latanowicz L, Vogel E, Limbach H.H. A 15N NMR study of proton localization and proton transfer thermodynamics and kinetics in polycrystalline porphycene. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2000;13:23–34. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1395(200001)13:1<23::AID-POC211>3.0.CO;2-W [Google Scholar]

- Langer U, Latanowicz L, Hoelger C, Buntkowsky G, Vieth H.M, Limbach H.H. 15N and 2H NMR relaxation and kinetics of stepwise double proton and deuteron transfer in polycrystalline tetraaza[14]annulene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001;3:1446–1458. doi:10.1039/b007564g [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z.X, Lee T, Resing K.A, Ahn N.G, Klinman J.P. Thermal-activated protein mobility and its correlation with catalysis in thermophilic alcohol dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9556–9561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403337101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403337101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbach H.H, Gerritzen D. Discussion remarks. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1982;74:279–296. doi:10.1039/dc9827400229 [Google Scholar]

- Limbach H.H, Hennig J, Gerritzen D, Rumpel H. Primary kinetic HH/HD/DH/DD isotope effects and proton tunnelling in double proton-transfer reactions. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1982;74:229–243. doi:10.1039/dc9827400229 see also pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Limbach H.H, Klein O, Lopez Del Amo J.M, Elguero J. Multiple kinetic hydrogen/deuterium isotope effects in quadruple proton transfer reactions. Z. Phys. Chem. 2004a;217:17–49. [Google Scholar]

- Limbach H.H, Pietrzak M, Benedict H, Tolstoy P.M, Golubev N.S, Denisov G.S. Empirical corrections for quantum effects in geometric hydrogen bond correlations. J. Mol. Struct. 2004b;706:115–119. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2004.03.006 [Google Scholar]

- Limbach H.H, Denisov G.S, Golubev N.S. Hydrogen bond isotope effects studied by NMR. In: Kohen A, Limbach H.H, editors. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. ch. 7. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2005a. pp. 193–252. [Google Scholar]

- Limbach H.H, Männle F, Detering C, Denisov G.S. Dynamic NMR studies of base-catalyzed intramolecular single vs. intermolecular double proton transfer of 1,3-bis(4-fluorophenyl)triazene. Chem. Phys. 2005b;319:69–92. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2005.05.021 [Google Scholar]

- Loth K, Graf F, Günthard H. Chemical exchange dynamics and structure of intramolecular O⋯H⋯O bridges: an ESR and INDO study of 2-hydroxy- and 2,6-dihydroxy-phenoxyl. Chem. Phys. 1976;13:95–113. doi:10.1016/0301-0104(76)80013-4 [Google Scholar]

- Maity D.K, Bell R.L, Truong T.N. Mechanism and quantum mechanical tunneling effects on inner hydrogen atom transfer in free base porphyrin: a direct ab initio dynamics study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:897–906. doi:10.1021/ja9925094 [Google Scholar]

- Männle F, Limbach H.H. Observation of an intramolecular base-catalyzed proton transfer in 1,3-di-(4-fluorphenyl)-triazene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1996;35:441–442. doi:10.1002/anie.199604411 [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R.A. On the analytical mechanics of chemical reactions. Quantum mechanics of linear collisions. J. Chem. Phys. 1966;45:4493–4499. doi:10.1063/1.1727528 [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M.H.M, Siegbahn P.E.M, Warshel A. Simulating large nuclear quantum mechanical corrections in hydrogen atom transfer reactions in metalloenzymes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003;9:96–99. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M.H.M, Siegbahn P.E.M, Warshel A. Simulations of the large kinetic isotope effect and the temperature dependence of the hydrogen atom transfer in lipoxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2820–2828. doi: 10.1021/ja037233l. doi:10.1021/ja037233l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokofiev A.I, Bubnov N.N, Solodnikov S.P, Kabachnik M.I. A kinetic isotope effect of the intramolecular hydrogen migration within 2-oxy-3,6-di-tert-butylphenoxy radical. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973;14:2479–2480. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)96183-0 [Google Scholar]

- Siebrand W, Wildman T.A, Zgierski M.Z. Golden-rule treatment of hydrogen-transfer reactions. 1. Principles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984a;106:4083–4089. doi:10.1021/ja00327a003 [Google Scholar]

- Siebrand W, Wildman T.A, Zgierski M.Z. Golden-rule treatment of hydrogen-transfer reactions. 2. Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984b;106:4089–4096. doi:10.1021/ja00327a004 [Google Scholar]

- Smedarchina Z, Zgierski M.Z, Siebrand W, Kozlowski P.M. Dynamics of tautomerism in porphine: an instanton approach. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;109:1014–1024. doi:10.1063/1.476644 [Google Scholar]

- Smedarchina Z, Siebrand W, Fernández-Ramos A. Kinetic isotope effects in multiple proton transfer. In: Kohen A, Limbach H.H, editors. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. ch. 20. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2005. pp. 521–548. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner T. Lengthening of the N–H bond in NHN hydrogen bonds. Preliminary structural data and implications of the bond valence concept. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1995:1331–1332. doi:10.1039/c39950001331 [Google Scholar]

- Steiner T. Lengthening of the covalent X–H bond in heteronuclear hydrogen bonds quantified from organic and organometallic neutron crystal structures. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:7041–7052. doi:10.1021/jp981604g [Google Scholar]

- Truhlar D.G. Variational transition-state theory and multidimensional tunneling for simple and complex reactions in the gas phase, solids, liquids, and enzymes. In: Kohen A, Limbach H.H, editors. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. ch. 22. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 579–620. [Google Scholar]

- Truhlar D.G, Kohen A. Convex Arrhenius plots and their interpretation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:848–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.848. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.3.848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangberg T, Ghosh A. Monodeprotonated free base porphyrin. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:1496–1497. doi:10.1021/jp963408k [Google Scholar]