Abstract

The cellular stress response protein GADD34 mediates growth arrest and apoptosis in response to DNA damage, negative growth signals, and protein malfolding. GADD34 binds to protein phosphatase PP1 and can attenuate the translational elongation of key transcriptional factors through dephosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α). Recently, we reported the involvement of human SNF5/INI1 (hSNF5/INI1) protein in the functions of GADD34 and showed that hSNF5/INI1 binds GADD34 and stimulates the bound PP1 phosphatase activity. To better understand the regulatory and functional mechanisms of GADD34, we undertook a yeast two-hybrid screen with full-length GADD34 as bait in order to identify additional protein partners of GADD34. We report here that human cochaperone protein BAG-1 interacts with GADD34 in vitro and in SW480 cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor z-LLL-B to induce apoptosis. Two other proteins, Hsp70/Hsc70 and PP1, associate reversibly with the GADD34-BAG-1 complex, and their dissociation is promoted by ATP. BAG-1 negatively modulates GADD34-bound PP1 activity, and the expression of BAG-1 isoforms can also mask GADD34-mediated inhibition of colony formation and suppression of transcription. Our findings suggest that BAG-1 may function to suppress the GADD34-mediated cellular stress response and support a role for BAG-1 in the survival of cells undergoing stress.

The eventual fate of cells following exposure to genotoxic stress is determined by signaling from competing pathways favoring either death or survival. The subsequent down-regulation of both p53-dependent and -independent apoptosis pathways may be key to both cell survival and oncogenesis. The growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein GADD34 mediates growth arrest and apoptosis in response to stress signals elicited by genotoxic stress, amino acid deprivation, and protein malfolding at the endoplasmic reticulum (21, 22, 35). The GADD34 transcript is stabilized under conditions of cellular stress, leading to the observed rise in its mRNA level independent of cellular p53 status (24).

The GADD34 protein harbors a highly conserved carboxy-terminal peptide domain homologous to herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) ICP34.5, a virulence factor that blocks the premature shutoff of protein synthesis in HSV-1-infected neuroblastoma cells and allows HSV-1-infected cells to circumvent apoptosis (6, 10, 11, 19). Both ICP34.5 and mammalian GADD34 engage protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) and target dephosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation elongation factor eIF2α (13, 20). In HSV-1-infected cells, this molecular event enables protein synthesis (19). In mammalian cells, the dephosphorylation attenuates eIF2α-mediated induction of stress-responsive genes and has been proposed in feedback regulation of cellular stress response initiated by protein malfolding at the endoplasmic reticulum (35).

The mechanism and regulation of GADD34-mediated growth suppression and apoptosis remain poorly understood. Recently we reported the association of the human SNF5 protein (hSNF5/INI1), a member of the hSWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, with GADD34 (1). We showed that hSNF5/INI1 may function as a regulatory subunit for PP1 (60). hSNF5/INI1, GADD34, and PP1 can coexist in a stable heterotrimeric complex. The disruption of the association between hSNF5/INI1 and GADD34 by the coexpression of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 2 interferes with the GADD34-mediated growth-inhibitory function in NIH 3T3 cells harboring a constitutively active12V-Ha Ras. Previously, we also showed that the chimeric leukemic HRX fusion protein, generated as a result of chromatin translocation in acute leukemia involving the 11q23 locus, also inhibits GADD34-mediated apoptosis in p53-defective SW480 cells exposed to UV irradiation (1). GADD34 has also been shown to bind the Src-related tyrosine kinase Lyn (16) and to be phosphorylated by Lyn in response to DNA damage. Although both Lyn and GADD34 have both been implicated in DNA damage response, coexpression of Lyn curiously interferes with GADD34-mediated apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Together, these findings suggest that the GADD34-mediated stress response may require tight cellular control and that viral and leukemic proteins may target GADD34 in order to gain survival advantage.

Bcl-2-associated athanogene protein BAG-1 is a multifunctional protein initially identified to bind Bcl-2 and augments Bcl-2-mediated antiapoptotic function (50). BAG-1 appears to form complexes with several other proteins including a number of nuclear hormone receptors (7, 26, 58, 66), the serine/threonine protein kinase Raf-1 (55), two members of tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor family (3, 29), the p53-indicible negative growth regulator Siah (30), and, most notably, the heat shock-inducible chaperone protein Hsp70/Hsc70 (5, 49). BAG-1 binds to the ATPase domain of Hsp70/Hsc70 (45) and stimulates the ATPase activity. It also modulates the substrate affinity of Hsp70/Hsc70 chaperone complex (5, 48, 49). Human BAG-1 exists in four isoforms (p50, p46, p33, and p29) as result of alternative translations from the BAG-1 mRNA (38, 62). These protein isoforms differ in their amino termini and in their subcellular localization and tissue distribution (62). The largest isoform BAG-1/p50 (also known as BAG-1L) is translated from a noncanonical CUG start site and contains an amino-terminal nuclear localization domain. BAG-1/p50 stimulates the androgen receptor transcription function through its amino terminus, which also associates with Hsp70/Hsc70 (15). The overexpression of BAG-1 isoforms p50, p46, and p33 in C33A cervical carcinoma cells confers resistance of these cells to apoptosis-inducing agents; BAG-1/p29, however, failed to protect these cells from the same stimuli (9). Recently, BAG-1 has been proposed to coordinate cell growth signals as a part of the heat shock response based on the observation that Hsp70/Hsc70 can competitively disrupt the BAG-1-Raf-1 kinase complex, thereby arresting DNA synthesis (46).

In the present study, we report the identification of BAG-1 as a protein partner to GADD34. We show that BAG-1 isoforms bind GADD34 through their common carboxy terminus both in vitro and in vivo. Using the proteasome inhibitor sodium benzyloxycarbonyl-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-leucyl boronic acid (z-LLL-B) to induce GADD34 in SW480 cells, we demonstrate the association of these two proteins during apoptosis. The GADD34-BAG-1 complex can also bind reversibly to endogenous Hsp70/Hsc70 and PP1. The composition of this multiprotein complex is determined in part by ATP, which reduces the associations of these two proteins with the complex. BAG-1 negatively regulates the GADD34-bound PP1 activity, and the expression of BAG-1 also masks GADD34-mediated growth suppression and reverses GADD34 inhibition of general transcription. These results suggest that BAG-1 may function to suppress the GADD34-mediated cellular stress response and may facilitate cell survival under conditions of stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast two-hybrid screen.

The reagents and yeast strains were used as specified by the manufacturer (Clontech). Briefly, full-length GADD34 was subcloned into the pGBK-T7 vector to generate the bait construct (pGBK-GADD34) for the two-hybrid screen. The bait plasmid was used to transform Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109, and the yeast transformant was mated with Y187 yeast strain expressing the GAL4 activation domain-human cDNA fusion protein library derived from pooled normal donor bone marrow RNA (Clontech). The diploid yeast colonies were screened for the transactivation of ADE2, HIS3, MEL1, and lacZ reporter genes. The library plasmid (pACT) of the positive clones was isolated and sequenced to determine the identity of the insert. The inserts were recloned into the pGAD-T7 vector, retransformed into Y187, and mated with AH109 containing pGBK-GADD34 to reconfirm the transactivation of reporter genes on Leu− Trp− Ade− His− (QDO) plates supplemented with X-α-Gal (Clontech).

Generation of BAG-1 and GADD34 plasmids.

Generation of the expression vectors for GADD34 was described previously (42). The expression plasmids for BAG-1 isoforms and the ΔUBQ mutant were generated by subcloning of appropriate PCR fragments into the KpnI-EcoRI sites of pSG5-FL2 vector.

Cell line transfection and drug exposure.

Human 293T, SW480 (American Type Culture Collection), and NIH 3T3-ras cells (a gift from R. Bruce Montgomery) were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Bio-Whittaker) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Bio-Whittaker) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. For coimmunoprecipitation analysis, the indicated expression plasmids (10 μg) were transfected by the calcium phosphate method into 293T cells (1, 8, 59). The transfection medium was replaced at 24 h, and the cells were allowed to recover for an additional 24 h. For colony formation assays, the indicated plasmids (5-12.5 μg), along with the marker plasmids, were transfected into NIH 3T3-ras cells with the Superfect reagent (Qiagen) as recommended by the manufacturer. In the colony formation assays, the selective antibiotic puromycin (2 μg/ml) was added 24 h following transfection. z-LLL-B (Affinity Research) and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS; Sigma) in dimethyl sulfoxide were added directly to the growth media.

Flow cytometry and apoptosis ladder assay.

Untreated and z-LLL-B-treated SW480 cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, stored in 70% ethanol, stained with propidium iodide (400 μg/ml), and analyzed on a Beckton-Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer. Total DNA was also harvested from these cells at the indicated times and analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel to detect the presence of the 100-bp DNA ladder.

Coimmunoprecipitation analysis.

Cytoplasmic extracts prepared from SW480 cells by the Dignam method (32) or whole-cell lysates from transfected 293T cells described previously (60) were immunoprecipitated with either anti-GADD34 (H193; Santa Cruz) or anti-Myc antibodies (9E10) at a 1:20 concentration for 2 h at 4°C. The immune complexes were captured with protein A-Sepharose beads and washed with 2× lysis buffer (1× lysis buffer is 40 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 100 mM NaCl, 0.4% NP-40, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 50 mM NaF, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors [Complete Mini-EDTA free; Roche]) four times, and the bound proteins were eluted with 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate SDS sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 1% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.28 M β-mercaptoethanol, 0.001% bromphenol blue) at 98°C for 5 min. The proteins were then separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% polyacrylamide) (PAGE) and transferred onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). Immunodetection of the proteins was carried out at the indicated antibody concentrations: 1:1,000 for anti-Myc and anti-FLAG M2 (Eastman-Kodak), 1:250 for anti-GADD34, anti-BAG-1 (NeoMarkers), anti-Hsc70 (W-27, Santa Cruz), and anti-PP1 (06-221, Upstate Biotechnology), and 1:10,000 for horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Sigma) by chemiluminescence (Pierce).

GST-binding assays.

In vitro-transcribed-translated 35S-labeled full-length GADD34 was generated as described previously (1, 59). Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-BAG1/p46 was prepared from bacterial lysates as recommended by the manufacturer (Pharmacia) and adsorbed onto glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma).35S-labeled GADD34 was then mixed with glutathione-agarose, GST-bound agarose, or GST-BAG1/p46-bound agarose in 1× binding buffer (40 mM HEPES [pH 8.0], 10% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-50) for 1 h at 4°C. The agarose-bound proteins were then washed three times with 1× binding buffer and eluted with 2× SDS sample buffer. The eluents were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) and autoradiography carried out overnight at 25°C.

Colony formation assays.

A total of 2 × 104 to 5 × 104 cells were seeded onto 60-mm-diameter plates 16 to 24 h prior to transfection. At 24 h following plasmid transfection, the medium from each plate was changed and puromycin was added at the indicated concentration. The cells were maintained for 10 to 14 days, with fresh medium and drug replacement every 3 to 4 days. The number of colonies formed per plate was quantitatively determined following staining with crystal violet. Duplicate transfections were performed for each condition.

Protein phosphatase assays.

The substrate 32P-labeled histone (type III-SS; Sigma) was generated as previously described (28, 60) with the substitution of porcine heart protein kinase catalytic subunit (5 U/ml) (Sigma), precipitated twice with 20% trichloroacetic acid, and washed extensively with cold acetone. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). In vitro protein phosphatase assays were carried out in phosphatase buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol) with 20 μg of 32P-labeled histone per reaction, in the presence of the indicated amount of anti-Myc immunoprecipitates at 30°C for 1 to 2 h in 100 μl of reaction mixture. Okadaic acid (Calbiochem) or a nuclear inhibitor of PP1 (Calbiochem) was included in indicated samples. The immune complexes immobilized on protein A-Sepharose were first washed twice with 1× immunoprecipitation buffer and then once with the phosphatase buffer before the phosphatase assay (28). The reactions were terminated with 200 μl of 20% trichloroacetic acid, the mixtures were centrifuged for 5 min, and 200-μl volumes of the supernatant were counted by Cerenkov counting.

RESULTS

Human BAG-1 interacts with GADD34 in yeast and mammalian cells.

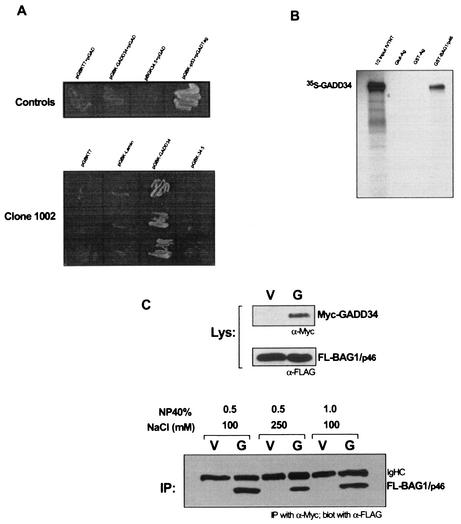

To better understand the functional mechanism of GADD34, a yeast two-hybrid screen was carried out using full-length GADD34 as bait to identify potential protein partners. In this screen, yeast strain AH109 harboring an expression construct for chimeric GADD34-GAL4 DNA binding domain fusion protein was mated with yeast strain Y187 harboring a cDNA library derived from pooled normal donor bone marrow fused to the GAL4 activation domain. Approximately 5 × 107 CFU was screened on appropriate nutrient-deficient agar plates. Three independent cDNA clones encoding in-frame BAG-1 cDNA sequences were isolated. All three clones encode amino acids 26 to 345 of BAG-1/p50 encompassing full-length sequences of BAG-1/p46, BAG-1/p33, and BAG-1/p29. The specific interaction of GADD34 with clone 1002 in yeast is depicted in Fig. 1A (lower panel). Only yeast mating involving GAL4-BD-GADD34 resulted in transactivation of reporter genes that allowed for growth of diploid yeast colonies in the high-stringency agar plates. Clone 1002 does not exhibit interaction with GAL4-BD-γ134.5 encoding amino acids 537 to 630 of GADD34, a domain homologous to HSV-1 ICP34.5.

FIG. 1.

Interaction of GADD34 with BAG-1 isoforms in vitro and in vivo. (A) Protein-protein interactions were assessed by mating yeast strain AH109 harboring the indicated pGBKT7 vector with yeast strain Y187 harboring the indicated pGAD vector containing the indicated cDNA insert. (Top) Relevant positive and negative YTH controls. (Bottom) Mating between three independent clones of Y187/ pGAD-1002 (BAG-1) with AH109 containing the indicated pGBK-T7 bait constructs. (B) In vitro-transcribed-translated 35S-labeled GADD34 was adsorbed onto glutathione-agarose (Glut-Ag), GST-bound agarose (GST-Ag), or GST-BAG-1/p46-bound agarose (GST-BAG1/p46). The autoradiogram of bound [35S]GADD34 and half of the input GADD34 is shown. (C) Lysates from 293T cells cotransfected with pSG5-FL-BAG-1/p46 and either the empty pCS2/MT vector (V) or pCS2/MT-GADDfull length (G) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc antibodies, adsorbed onto protein A-Sepharose beads, and washed in buffers containing the indicated concentration of NP-40 and NaCl. Lysates (Lys) and bound proteins (IP) were determined by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. IgHC, immunoglobulin heavy chain.

To confirm the interaction of BAG-1 and GADD34, we examined the protein association by using both GST pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation assays. In the experiment in Fig. 1B, in vitro-transcribed and -translated 35S-labeled full-length GADD34 was tested for its ability to bind glutathione-bound, GST-bound, or GST-BAG-1/p46-bound agarose. Following washing, GADD34 was found to bind selectively to the GST-BAG-1/p46-bound agarose. To determine whether these proteins might associate in mammalian cells, we coexpressed Myc-GADD34 and FLAG-BAG-1/p46 in 293T cells and examined the ability of anti-Myc antibodies to coprecipitate FLAG-BAG-1/p46 with myc-GADD34 in cell lysates (Fig. 1C). We found that FLAG-BAG-1/p46 could be coprecipitated with Myc-GADD34 and that the association is stable in buffer containing 250 mM NaCl or 1% NP-40 (Fig. 1C, lower panel).

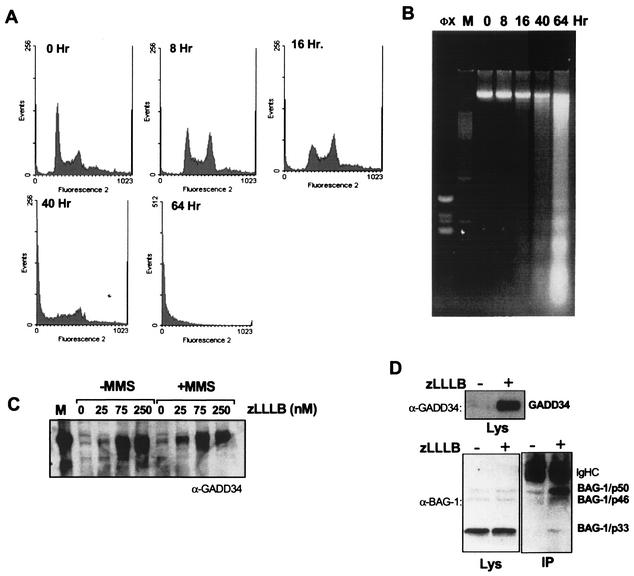

GADD34 associates with BAG-1 in proteasome inhibitor z-LLL-B-treated SW480 cells undergoing apoptosis.

Proteasome inhibitor z-LLL-B is a cell-permeable leupeptin analogue that inhibits the “chymotrypsin-like” and “post-glutamyl” hydrolase activities of the human 20S proteasome (36). z-LLL-B induces apoptosis in MOLT-4 and L5178Y cells via a p53-dependent pathway (44). In the p53-defective SW480 colon carcinoma cells, z-LLL-B at 50 to 250 nM arrested the cell proliferation primarily at G2/M 8 h following exposure (Fig. 2A) and induced detectable apoptosis as early as 16 to 24 h. The apoptosis was confirmed by a rising sub-G1 fraction on the propidium iodide DNA histogram (Fig. 2A) and the presence of the apoptotic DNA ladder (Fig. 2B). Coincidentally with apoptosis, GADD34, whose level is normally barely above the threshold of detection, accumulated in the treated SW480 cells in a z-LLL-B concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). The addition of an alkylating agent, MMS, known to increase GADD34 transcripts in SW480 cells at an optimal concentration of 0.1 μM had only a minimal effect on the z-LLL-B induction of the GADD34 protein at 24 h (Fig. 2C). Utilizing z-LLL-B to induce a high level of endogenous GADD34, we tested the associations of BAG-1 and GADD34 in SW480 cells by a coimmunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 2D). BAG-1/p50, BAG-1/p46, and BAG-1/p33 isoforms were found in SW480 cell lysates, with BAG-1/p33 being the predominant form. Their levels were unaltered by z-LLL-B. All three were found to coprecipitate to various extents with GADD34 in the cytoplasmic extracts from z-LLL-B-treated cells, with BAG-1/p50 being found preferentially in complex with GADD34. These results suggest that a portion of the BAG-1 proteins can complex with GADD34 in mammalian cells undergoing apoptosis.

FIG. 2.

GADD34 induction by z-LLL-B and interaction with endogenous BAG-1/p33. (A) DNA histogram of propidium iodide-labeled SW480 cells at the indicated times following treatment with 250 nM z-LLL-B. (B) DNA ladder analysis carried out for z-LLL-B-treated cells at the indicated times. Markers: M, 100-bp DNA ladder; ΦX, ΦX/HaeIII. (C) Immunoblot of SW480 cell lysates with anti-GADD34 antibodies 24 h following treatment with z-LLL-B at the indicated concentration with or without 0.1 μM MMS. (D) Equivalent amounts of cytoplasmic extract were immunoprecipitated with anti-GADD34 antibodies. Proteins in the extracts (Lys) and in the immune complexes (IP) were determined with the indicated antibodies on Western analysis.

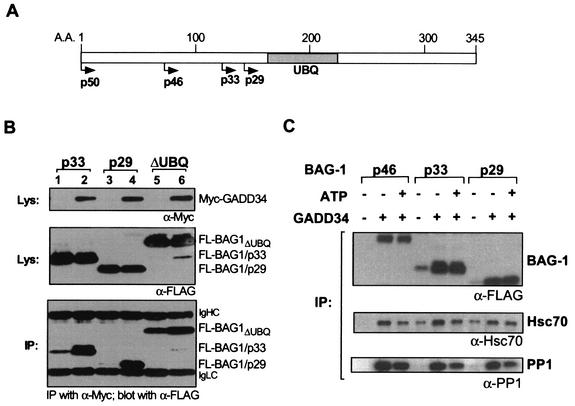

Human BAG-1 isoforms bind GADD34 through a shared carboxy terminus, and Hsp70/Hsc70 and PP1 interact reversibly with this complex.

We next determined the region on BAG-1 that binds to GADD34 by testing the ability of full-length GADD34 to bind other BAG-1 isoforms (p33 and p29) and a mutant BAG-1/p46 missing the ubiquitin-like region (amino acids 169 to 216) with homologies to ubiquitin and the ubiquitin family of proteins (4). The results in Fig. 3B show that GADD34 binds to all three BAG-1 proteins that have the common carboxy-terminal region (amino acids 216 to 345), as evidenced by the larger amounts of all three BAG-1 proteins immunoprecipitated by the anti-Myc antibodies in the presence of Myc-GADD34 compared with the nonspecific precipitation of BAG-1/p33 and ΔUBQ by the same antibodies. The ubiquitin-like region on BAG-1 was found to be unnecessary for this association. Of note, the preferential association of BAG-1/p50 with GADD34 in SW480 cells (shown in Fig. 2D) suggests that there may also be other unique sequences in the amino terminus of BAG-1/p50 that can mediate its direct or indirect association with GADD34.

FIG. 3.

The binding of BAG-1 isoforms with GADD34 and the modulation of ATP on associated proteins. (A) Schematic of BAG-1 protein isoforms, with the shaded box indicating the position of the ubiquitin-like domain (UBQ). (B) GADD34 interaction with BAG-1 isoforms. Coimmunoprecipitation (IP) analysis was carried out with 293T cells expressing (FLAG-tagged BAG-1/p33 (lanes 1 and 2), FLAG-tagged BAG-1/p29 (lanes 3 and 4), or FLAG-tagged BAG-1ΔUBQ (lanes 5 and 6) with (lanes 1, 3 and 5) or without (lanes 2, 4, and 6) Myc-GADD34. Lysates (Lys) were blotted with anti-Myc or anti-FLAG to determine the level of protein expression. Anti-Myc immunoprecipitates were blotted with anti-FLAG to determine the levels of bound FL-BAG-1/p33, FL-BAG-1/p29, and FL-BAG-1ΔUBQ (lower panel). IgHC, immunoglobulin heavy chain; IgLC, immunoglobulin light chain. (C) ATP modulation of the binding of endogenous Hsp70/Hsc70 and PP1 to the GADD34-BAG-1 complex. Coimmunoprecipitation analysis was carried out with 293T cells overexpressing GADD34 and the indicated BAG-1 isoforms in either the presence or the absence of 10 mM ATP. Coprecipitated proteins were detected with the indicated antibodies.

Since the carboxy terminus of BAG-1 also binds to Hsp70/Hsc70, we examined the possibility that endogenous Hsp70/Hsc70 may be associated with the GADD34-BAG-1 protein complex and whether the presence of ATP, which modulates the association of Hsp70/Hsc70 with both BAG-1 and Bcl-2, affected these protein interactions (34, 49, 65). In the experiment in Fig. 3C, immunoprecipitation of BAG-1 isoforms with Myc-GADD34 was performed with the anti-Myc antibodies in buffers that either did or did not include 10 mM ATP. The levels of coprecipitated BAG-1 and endogenous Hsp70/Hsc70 were determined on immunoblots. ATP was found to weaken the association of Hsp70/Hsc70 with GADD34-BAG-1/p46 and GADD34-BAG-1/p33 protein complexes but minimally affected Hsp70/Hsc70 association with p29. The interaction of GADD34 with BAG-1 itself was also unaltered by the presence of ATP. We also determined whether endogenous PP1 can bind to this complex and investigated the influence of ATP on the PP1 association. The lower panel of Fig. 3C demonstrates that endogenous PP1 can bind to the GADD34-BAG-1 protein complexes, and, surprisingly, PP1 was also partially released from these complexes by ATP. Since PP1 does not bind either to BAG-1 or Hsp70/Hsc70 (data not shown), these results suggest that ATP probably induces a conformational change in the GADD34-BAG-1 complex that affects the affinity of PP1 for GADD34. The findings here also imply that GADD34 and BAG-1 may exist in a protein complex that includes other protein partners that may bind reversibly in an ATP-dependent manner.

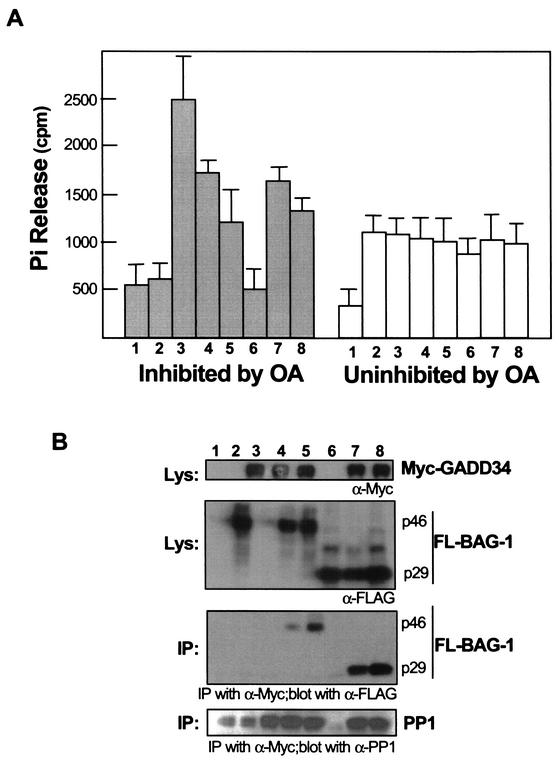

BAG-1 isoforms negatively modulate GADD34-associated phosphatase activity.

We proceeded to examine whether BAG-1 affects the GADD34-bound PP1 phosphatase activity. In the experiments in Fig. 4, we isolated GADD34 complexes immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibodies from 293T cells transfected with a Myc-GADD34 expression plasmid. These GADD34 complexes were previously found to be associated with phosphatase activities that can be differentiated based on their sensitivity to either okadaic acid (OA) or to NIPP1, a selective inhibitor for PP1 (18, 25, 53). We cotransfected increasing amounts of BAG1/p46 or BAG-1/p29 to determine if the BAG1 association will influence GADD34-bound PP1 activity. In the experiment in Fig. 4A, the PP1-specific phosphatase activity associated with the GADD34 immune complex was determined by measuring the fraction of the total phosphatase activity that could be inhibited by 50 nM OA. Both OA-inhibited and -uninhibited phosphatase activities have been found, and the results show that increasing levels of either BAG-1/p46 or BAG-1/p29 reduced GADD34-associated PP1 activities. In contrast, the OA-uninhibited “nonspecific” phosphatase activities remained unaffected by BAG-1. Although 50 nM OA inhibits the phosphatase activities of both PP1 and PP2A, we have shown previously that only PP1 is bound to the overexpressed GADD34 (60). These results were further confirmed with the PP1 selective inhibitor NIPP1 (data not shown). The immunoblots shown in Fig. 4B depict the levels of BAG-1 and GADD34 expression and the level of coprecipitated BAG-1 and endogenous PP1. Both BAG-1 isoforms failed to displace endogenous PP1 that was bound to GADD34, since this level (lanes 3 to 5, 7 and 8) remained significantly above the level of PP1 nonspecifically bound to the Sepharose beads (lanes 1, 2, and 6). The reduction of GADD34-bound PP1 activity is therefore probably a result of either direct modulation by BAG-1 or displacement of an unidentified activation factor but is not a reflection of decreased levels of PP1 bound to GADD34.

FIG. 4.

Modulation of GADD34-bound PP1 phosphatase activity by BAG-1/p46 and p29. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with pCS2/MT (lane 1, 4 μg), pSG5-FL-BAG-1/p46 (lane 2, 8 μg), pCS2/MT-GADD34 (lanes 3 to 5, 4 μg) with increasing amounts of pSG5-FL-BAG-1/p46 (lane 4, 4 μg; lane 5, 8 μg), pSG5-FL-BAG1/p29 (lane 6, 8 μg), or pCS2/MT-GADD34 (lanes 7 and 8; 4 μg) with increasing amount of pSG5-FL-BAG1/p29 (lane 7, 4 μg; lane 8, 8 μg). The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibodies, adsorbed onto protein A-Sepharose, and assayed for phosphatase activity in the presence or absence of OA. The enzyme activities were measured at 60 min from triplicate transfection samples. Phosphatase activities either inhibited or uninhibited by OA are reported. (B) Proteins of the lysates and immunoprecipitation (IP) eluents from pooled duplicate samples were blotted with anti-Myc, anti-FLAG, or anti-PP1 antibodies, indicating the levels of specific proteins.

BAG-1 isoform coexpression masks GADD34 suppression of NIH 3T3-ras colony formation.

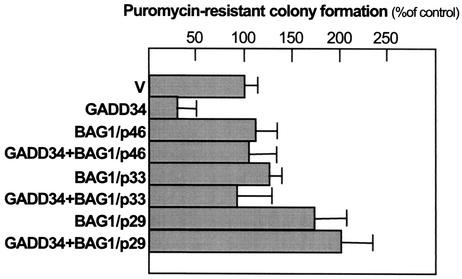

We recently demonstrated that the enforced expression of GADD34 in NIH 3T3-ras cells reduces the colony numbers in colony formation assays, probably due to both reduced survival and growth suppression (60). To assess the influence of BAG-1 protein expression on GADD34 function, we coexpressed BAG-1 isoforms and GADD34 along with an antibiotic selection plasmid (pBABEpuro) in NIH 3T3-ras cells and assayed for colony formation in the presence of puromycin (Fig. 5). A total of 20 to 200 colonies are typically scored on a 60-mm-diameter plate. The results from three independent experiments show that the overexpression of GADD34 reduced the colony formation by an average of 75% compared with that for NIH 3T3-ras cells transfected with an empty expression plasmid. The expression of BAG-1 isoforms p46 and p33 alone had no effect on colony formation, while the expression of BAG1/p29 alone appeared to promote colony formation by an average of 60%. When these BAG-1 isoform proteins were coexpressed with GADD34, the suppression effect of GADD34 in an NIH 3T3-ras colony formation assay was negated in these cells.

FIG. 5.

Effect of BAG-1 isoforms on GADD34 suppression of colony formation. NIH 3T3-ras cells transfected with empty plasmid vectors (V) or 5 μg of the indicated expression plasmids encoding GADD34, BAG-1/p46, BAG-1/p33, or BAG-1/p29 along with 1 μg of pBABEpuro were selected with 2 μg of puromycin per ml for 10 days. Plasmids were transfected in equal amounts into each plate. The number of visible colonies was determined from duplicate plates. The bar graph depicts the results from three independent experiments, with the colony scores normalized against the vector-only control.

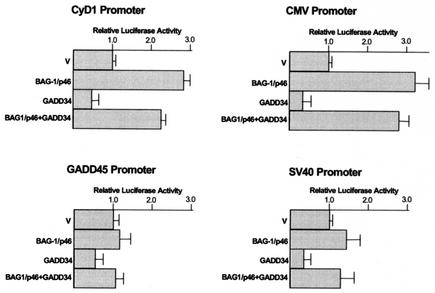

BAG-1 isoform coexpression reverses GADD34-mediated general transcription suppression.

GADD34 has a suppression effect on general transcription. In 293T, G401, and SW480 cells transfected with chimeric reporter constructs linked to constitutively activated promoters, GADD34 generally suppressed the reporter gene activity to 25 to 50% of the empty vector controls (not all data shown). The transcription suppression effect was independent of GADD34-mediated apoptosis since both the transfection efficiency, as determined by the expression of a cotransfected enhanced green fluorescent protein construct, and the level of expressed BAG-1 protein were unaltered in the presence of GADD34 (data not shown). The suppression effect was observed for nearly all constitutively activated promoter elements tested (CMVie, SV40, and cyclin D1) and the p53-dependent GADD45 promoter. To determine if BAG-1/p46 can interfere with this function, we tested the coexpression of BAG-1 on this observed GADD34 effect (Fig. 6). With all four promoters in 293T cells, BAG-1/p46 alone stimulated the promoter activity to various degrees and masked the GADD34-mediated transcription suppression when BAG-1/p46 was coexpressed with GADD34. Of note, BAG-1/p50 has been reported to bind directly to the CMV promoter element (15), and we have confirmed that this promoter is stimulated consistently to a greater extent.

FIG. 6.

Effect of BAG-1 isoforms on GADD34-mediated transcription suppression. The indicated chimeric luciferase reporter constructs linked to indicated promoters were cotransfected with expression constructs for GADD34 (3 μg) and/or BAG-1 (6 μg). The luciferase assay was performed on day 3. The luciferase activity relative to vector-only control (V) is reported from duplicate transfections.

DISCUSSIONS

In cells experiencing genotoxic, physiological, and environmental stress, GADD34 mediates a set of responses that include general repression of transcription and translation, growth arrest, and apoptosis. In this report, we present evidence that the prosurvival protein BAG-1 associates with GADD34 in a complex that can include at least two other proteins, Hsp70/Hsc70 and PP1. The coexpression of BAG-1 at a comparable level to GADD34 inhibits GADD34-bound PP1 phosphatase activity and masks both GADD34-mediated growth suppression and inhibition on general transcription. Taken together, these findings suggest that BAG-1 functions to down-regulate the GADD34-mediated stress response by directly binding to GADD34 and may therefore promote cell survival in cancers that aberrantly express BAG-1 proteins.

Mammalian BAG-1 has antiapoptotic and growth-regulatory functions in a number of settings. BAG-1 augments the antiapoptotic function of Bcl-2 since the enforced expression of the mouse BAG-1 protein in Jurkat cells stably expressing Bcl-2 confers resistance to Fas ligand; staurosporin, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated cell lysis in these cells (50). Similarly, the expression of BAG-1 either with heparin-bound epidermal growth factor in CHO cells or alone in cervical carcinoma cells has been reported to reduce the sensitivity of these cells to a variety of apoptotic stimuli (29, 64). Conversely, decreased levels of BAG-1 were found to precede olfactory neuronal apoptosis and may be related to ubiquitination of the BAG-1 protein (47). Since GADD34 facilitates apoptosis to these stimuli, the observed BAG-1 effect may be explained in part by its ability to interfere with GADD34 pathways that facilitate apoptosis. BAG-1 has been reported to reverse both Siah-1A- and p53-induced growth arrest in 293 cells without affecting p53-mediated transcription activity (30). Although the related protein murine Siah-1B is induced early after activation of p53 in leukemia cell lines (23), there is currently no direct evidence to suggest that Siah-1A plays a role in mediating cellular stress response.

The aberrant overexpression of BAG-1 has been reported in a number of naturally occurring human cancers and in cancer cell lines. BAG-1 overexpression has been estimated to occur in 50% of breast carcinomas (51, 54), 73% of non-small cell lung carcinomas (41), ≥80% of laryngeal carcinomas (61), 59% of oral squamous cell carcinomas (43), and 25 to 75% of cervical carcinomas (63, 64). The pattern of subcellular BAG-1 expression and BAG-1 isoform distribution in these cases requires further investigation. Using BAG-1 overexpression as a biomarker, prognostic stratification can be demonstrated for subsets of breast, cervical, head and neck, and lung cancers (41, 43, 51, 54, 61, 64). A consistent clinical effect of BAG-1 overexpression on prognosis has not been demonstrated, suggesting that BAG-1 may have pleiotropic effects in tumor cells depending on the environment, specific BAG-1 isoform expression pattern, and subcellular localization of the overexpressed proteins.

The cellular ATP concentration (and energy charge) has long been known to regulate a multitude of cellular physiological pathways, most notably involving metabolic, mitochondrial, contractile protein, and neuronal functions (17, 40, 56, 57). In stressed cells, the intracellular ATP concentration can drop precipitously from the normal concentration of 5 to 10 mM. A fall in the intracellular ATP level, commonly observed in dying cells, may also determine the mode of cell death (14, 27). ATP, which influences the function of a number of heat shock proteins, is known to induce molecular conformational change in Hsp70/Hsc70 (31, 37, 52). Here, we show that ATP reduces the affinity of both Hsp70/Hsc70 and PP1 for the BAG-1-GADD34 complex without disrupting the association of BAG-1 and GADD34. The association of BAG-1 with Bcl-2 has been previously shown to be stabilized by the presence of ATP (49). The interaction of the carboxy-terminal “BAG” domain on BAG-1 with the ATPase domain on Hsp70/Hsc70 results in a conformation change in both proteins such that the latter becomes incompatible to nucleotide binding (45). These ATP-dependent reversible protein associations raise the possibility that both the composition and function of the BAG-1-GADD34 complex may be regulated by ATP. Of note, subunits of PP1 have been reported to be in a phosphoprotein complex with Hsc70/Hsp70 and Hsp90 in resting platelets (39).

In addition to GADD34 and Hsp70/Hsc70, a number of other proteins interact with the carboxy terminus of BAG-1, including Bcl-2, Raf-1 kinase, and Siah-1A (30, 50, 55). Raf-1 and Hsp70/Hsc70 compete for binding to BAG-1 such that elevated levels of Hsp70/Hsc70 sequesters BAG-1 and down-regulates the BAG-1-mediated activation of Raf-1 kinase and its downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase effector pathways (46). BAG-1 has therefore been proposed to coordinate cell growth signals and mitogenesis, with Hsp70/Hsc70 functioning as a sensor in stress signaling. Our findings here suggest that GADD34 may also serve as a transducer of negative growth signals by binding to BAG-1 at the same carboxy terminus. The effect of GADD34 on BAG-1 functions remains to be determined; however, it is predicted to have negative regulatory consequences.

The proteasome is the central cellular enzyme complex that catalyzes the ATP-dependent proteolytic degradation of many rate-limiting enzymes, transcriptional regulators, and critical regulatory proteins (12, 33). Although the GADD34 transcript is induced by a variety of apoptosis-inducing agents, the GADD34 protein level in both unstressed and stressed cells is rarely above the level of detection, probably reflecting a tight regulation, in part by the proteasome system. Overexpression of GADD34 in eukaryotic cells results in growth arrest and facilitates apoptosis independent of functional p53 (22). We show here that the potent proteasome inhibitor z-LLL-B can elicit apoptosis in the p53-defective SW480 cells and cause a rapid accumulation of GADD34 protein. The mechanism underlying GADD34 accumulation by z-LLL-B probably involves both induction of GADD34 and interference of GADD34 degradation through inhibition of proteasome systems. BAG-1 has recently been shown to undergo polyubiquitylation in a ternary complex with Hsp70/Hsc70 and the ubiquitin ligase CHIP, resulting in the stimulation of a degradation-independent association of the BAG-1 with the proteasome (2). It is possible that GADD34 may be a target for the proteasome through its association with BAG-1. Proteasome inhibitors such as z-LLL-B may therefore potentiate the effect of other anticancer agents by up-regulating GADD34-mediated growth suppression and apoptosis, particularly in tumors with a high prevalence of p53 mutation. Proteasome inhibitors should also prove to be useful in the study of GADD34, whose low endogenous levels have precluded in vivo investigations.

Acknowledgments

We thank William Schubach for insightful discussions and Douglas Tkachuk for providing the GADD34 promoter construct.

This work was supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA Merit Review) and a grant from the NIH (5K08CA71928-01) to D.Y.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H. T., R. Chinery, D. Y. Wu, S. J. Kussick, J. M. Payne, A. J. Fornace, Jr., and D. C. Tkachuk. 1999. Leukemic HRX fusion proteins inhibit GADD34-induced apoptosis and associate with the GADD34 and hSNF5/INI1 proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7050-7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti, S., J. Demand, C. Esser, N. Emmerich, H. Schild, and J. Hohfeld. 2002. Ubiquitylation of BAG-1 suggests a novel regulatory mechanism during the sorting of chaperone substrates to the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45920-45927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardelli, A., P. Longati, D. Albero, S. Goruppi, C. Schneider, C. Ponzetto, and P. M. Comoglio. 1996. HGF receptor associates with the anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1 and prevents cell death. EMBO J. 15:6205-6212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer, P., A. Arndt, S. Metzger, R. Mahajan, F. Melchior, R. Jaenicke, and J. Becker. 1998. Structure determination of the small ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1. J. Mol. Biol. 280:275-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bimston, D., J. Song, D. Winchester, S. Takayama, J. C. Reed, and R. I. Morimoto. 1998. BAG-1, a negative regulator of Hsp70 chaperone activity, uncouples nucleotide hydrolysis from substrate release. EMBO J. 17:6871-6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassady, K. A., M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1998. The herpes simplex virus US11 protein effectively compensates for the gamma1(34.5) gene if present before activation of protein kinase R by precluding its phosphorylation and that of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2. J. Virol. 72:8620-8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cato, A. C., and S. Mink. 2001. BAG-1 family of cochaperones in the modulation of nuclear receptor action. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 78:379-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, C. A., and H. Okayama. 1988. Calcium phosphate-mediated gene transfer: a highly efficient transfection system for stably transforming cells with plasmid DNA. BioTechniques 6:632-638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J., J. Xiong, H. Liu, G. Chernenko, and S. C. Tang. 2002. Distinct BAG-1 isoforms have different anti-apoptotic functions in BAG-1-transfected C33A human cervical carcinoma cell line. Oncogene 21:7050-7059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou, J., and B. Roizman. 1992. The gamma 1(34.5) gene of herpes simplex virus 1 precludes neuroblastoma cells from triggering total shutoff of protein synthesis characteristic of programed cell death in neuronal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:3266-3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou, J., and B. Roizman. 1990. The herpes simplex virus 1 gene for ICP34.5, which maps in inverted repeats, is conserved in several limited-passage isolates but not in strain 17syn+. J. Virol. 64:1014-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conaway, R. C., C. S. Brower, and J. W. Conaway. 2002. Emerging roles of ubiquitin in transcription regulation. Science 296:1254-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connor, J. H., D. C. Weiser, S. Li, J. M. Hallenbeck, and S. Shenolikar. 2001. Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein GADD34 assembles a novel signaling complex containing protein phosphatase 1 and inhibitor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6841-6850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eguchi, Y., S. Shimizu, and Y. Tsujimoto. 1997. Intracellular ATP levels determine cell death fate by apoptosis or necrosis. Cancer Res. 57:1835-1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Froesch, B. A., S. Takayama, and J. C. Reed. 1998. BAG-1L protein enhances androgen receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 273:11660-11666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grishin, A. V., O. Azhipa, I. Semenov, and S. J. Corey. 2001. Interaction between growth arrest-DNA damage protein 34 and Src kinase Lyn negatively regulates genotoxic apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10172-10177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halestrap, A. P., E. Doran, J. P. Gillespie, and A. O'Toole. 2000. Mitochondria and cell death. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28:170-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie, D. G. 1993. Protein phosphorylation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 19.He, B., J. Chou, D. A. Liebermann, B. Hoffman, and B. Roizman. 1996. The carboxyl terminus of the murine MyD116 gene substitutes for the corresponding domain of the gamma(1)34.5 gene of herpes simplex virus to preclude the premature shutoff of total protein synthesis in infected human cells. J. Virol. 70:84-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He, B., M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1998. The gamma134.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 has the structural and functional attributes of a protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit and is present in a high molecular weight complex with the enzyme in infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20737-20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollander, M. C., M. S. Sheikh, K. Yu, Q. Zhan, M. Iglesias, C. Woodworth, and A. J. Fornace, Jr. 2001. Activation of Gadd34 by diverse apoptotic signals and suppression of its growth inhibitory effects by apoptotic inhibitors. Int. J. Cancer 96:22-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollander, M. C., Q. Zhan, I. Bae, and A. J. Fornace, Jr. 1997. Mammalian GADD34, an apoptosis- and DNA damage-inducible gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272:13731-13737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu, G., Y. L. Chung, T. Glover, V. Valentine, A. T. Look, and E. R. Fearon. 1997. Characterization of human homologs of the Drosophila seven in absentia (sina) gene. Genomics 46:103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackman, J., I. Alamo, Jr., and A. J. Fornace, Jr. 1994. Genotoxic stress confers preferential and coordinate messenger RNA stability on the five gadd genes. Cancer Res. 54:5656-5662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagiello, I., A. Van Eynde, V. Vulsteke, M. Beullens, A. Boudrez, S. Keppens, W. Stalmans, and M. Bollen. 2000. Nuclear and subnuclear targeting sequences of the protein phosphatase-1 regulator NIPP1: J. Cell Sci. 113:3761-3768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kullmann, M., J. Schneikert, J. Moll, S. Heck, M. Zeiner, U. Gehring, and A. C. Cato. 1998. RAP46 is a negative regulator of glucocorticoid receptor action and hormone-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:14620-14625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leist, M., B. Single, A. F. Castoldi, S. Kuhnle, and P. Nicotera. 1997. Intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentration: a switch in the decision between apoptosis and necrosis. J. Exp. Med. 185:1481-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, M., H. Guo, and Z. Damuni. 1995. Purification and characterization of two potent heat-stable protein inhibitors of protein phosphatase 2A from bovine kidney. Biochemistry 34:1988-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, J., L. Hutchinson, S. M. Gaston, G. Raab, and M. R. Freeman. 2001. BAG-1 is a novel cytoplasmic binding partner of the membrane form of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor: a unique role for proHB-EGF in cell survival regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:30127-30132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuzawa, S., S. Takayama, B. A. Froesch, J. M. Zapata, and J. C. Reed. 1998. p53-inducible human homologue of Drosophila seven in absentia (Siah) inhibits cell growth: suppression by BAG-1. EMBO J. 17:2736-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClellan, A. J., J. B. Endres, J. P. Vogel, D. Palazzi, M. D. Rose, and J. L. Brodsky. 1998. Specific molecular chaperone interactions and an ATP-dependent conformational change are required during posttranslational protein translocation into the yeast ER. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:3533-3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mercier, P. A., N. A. Winegarden, and J. T. Westwood. 1999. Human heat shock factor 1 is predominantly a nuclear protein before and after heat stress. J. Cell Sci. 112:2765-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myung, J., K. B. Kim, and C. M. Crews. 2001. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and proteasome inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 21:245-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nollen, E. A., A. E. Kabakov, J. F. Brunsting, B. Kanon, J. Hohfeld, and H. H. Kampinga. 2001. Modulation of in vivo HSP70 chaperone activity by Hip and Bag-1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:4677-4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novoa, I., H. Zeng, H. P. Harding, and D. Ron. 2001. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2alpha. J. Cell Biol. 153:1011-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orlowski, M., and S. Wilk. 2000. Catalytic activities of the 20 S proteasome, a multicatalytic proteinase complex. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 383:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osipiuk, J., M. A. Walsh, B. C. Freeman, R. I. Morimoto, and A. Joachimiak. 1999. Structure of a new crystal form of human Hsp70 ATPase domain. Acta Crystallogr. Ser. D 55:1105-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Packham, G., M. Brimmell, and J. L. Cleveland. 1997. Mammalian cells express two differently localized Bag-1 isoforms generated by alternative translation initiation. Biochem. J. 328:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polanowska-Grabowska, R., C. G. Simon, Jr., R. Falchetto, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and A. R. Gear. 1997. Platelet adhesion to collagen under flow causes dissociation of a phosphoprotein complex of heat-shock proteins and protein phosphatase 1. Blood 90:1516-1526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Racay, P., P. Kaplan, and J. Lehotsky. 1996. Control of Ca2+ homeostasis in neuronal cells. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 15:193-210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rorke, S., S. Murphy, M. Khalifa, G. Chernenko, and S. C. Tang. 2001. Prognostic significance of BAG-1 expression in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 95:317-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roth, M. B., A. M. Zahler, and J. A. Stolk. 1991. A conserved family of nuclear phosphoproteins localized to sites of polymerase II transcription. J. Cell Biol. 115:587-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shindoh, M., M. Adachi, F. Higashino, M. Yasuda, K. Hida, T. Nishioka, M. Ono, S. Takayama, J. C. Reed, K. Imai, Y. Totsuka, and T. Kohgo. 2000. BAG-1 expression correlates highly with the malignant potential in early lesions (T1 and T2) of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 36:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shinohara, K., M. Tomioka, H. Nakano, S. Tone, H. Ito, and S. Kawashima. 1996. Apoptosis induction resulting from proteasome inhibition. Biochem. J 317:385-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sondermann, H., C. Scheufler, C. Schneider, J. Hohfeld, F. U. Hartl, and I. Moarefi. 2001. Structure of a Bag/Hsc70 complex: convergent functional evolution of Hsp70 nucleotide exchange factors. Science 291:1553-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song, J., M. Takeda, and R. I. Morimoto. 2001. Bag1-Hsp70 mediates a physiological stress signalling pathway that regulates Raf-1/ERK and cell growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:276-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sourisseau, T., C. Desbois, L. Debure, D. D. Bowtell, A. C. Cato, J. Schneikert, E. Moyse, and D. Michel. 2001. Alteration of the stability of Bag-1 protein in the control of olfactory neuronal apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 114:1409-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stuart, J. K., D. G. Myszka, L. Joss, R. S. Mitchell, S. M. McDonald, Z. Xie, S. Takayama, J. C. Reed, and K. R. Ely. 1998. Characterization of interactions between the anti-apoptotic protein BAG-1 and Hsc70 molecular chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22506-22514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takayama, S., D. N. Bimston, S. Matsuzawa, B. C. Freeman, C. Aime-Sempe, Z. Xie, R. I. Morimoto, and J. C. Reed. 1997. BAG-1 modulates the chaperone activity of Hsp70/Hsc70. EMBO J. 16:4887-4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takayama, S., T. Sato, S. Krajewski, K. Kochel, S. Irie, J. A. Millan, and J. C. Reed. 1995. Cloning and functional analysis of BAG-1: a novel Bcl-2-binding protein with anti-cell death activity. Cell 80:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang, S. C., N. Shaheta, G. Chernenko, M. Khalifa, and X. Wang. 1999. Expression of BAG-1 in invasive breast carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 17:1710-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theyssen, H., H. P. Schuster, L. Packschies, B. Bukau, and J. Reinstein. 1996. The second step of ATP binding to DnaK induces peptide release. J. Mol. Biol. 263:657-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trinkle-Mulcahy, L., P. Ajuh, A. Prescott, F. Claverie-Martin, S. Cohen, A. I. Lamond, and P. Cohen. 1999. Nuclear organisation of NIPP1, a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 that associates with pre-mRNA splicing factors. J. Cell Sci. 112:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turner, B. C., S. Krajewski, M. Krajewska, S. Takayama, A. A. Gumbs, D. Carter, T. R. Rebbeck, B. G. Haffty, and J. C. Reed. 2001. BAG-1: a novel biomarker predicting long-term survival in early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 19:992-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, H. G., S. Takayama, U. R. Rapp, and J. C. Reed. 1996. Bcl-2 interacting protein, BAG-1, binds to and activates the kinase Raf-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7063-7068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wijker, J. E., P. R. Jensen, J. L. Snoep, A. Vaz Gomes, M. Guiral, A. P. Jongsma, A. de Waal, S. Hoving, S. van Dooren, C. C. van der Weijden, et al. 1995. Energy, control and DNA structure in the living cell. Biophys. Chem. 55:153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winder, W. W. 2001. Energy-sensing and signaling by AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 91:1017-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Witcher, M., X. Yang, A. Pater, and S. C. Tang. 2001. BAG-1 p50 isoform interacts with the vitamin D receptor and its cellular overexpression inhibits the vitamin D pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 265:167-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu, D. Y., G. V. Kalpana, S. P. Goff, and W. H. Schubach. 1996. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 (EBNA2) binds to a component of the human SNF-SWI complex, hSNF5/Ini1. J. Virol. 70:6020-6028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu, D. Y., D. C. Tkachuk, R. S. Roberson, and W. H. Schubach. 2002. The human SNF5/INI1 protein facilitates the function of the growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein (GADD34) and modulates GADD34-bound protein phosphatase-1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27706-27715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamauchi, H., M. Adachi, K. Sakata, M. Hareyama, M. Satoh, T. Himi, S. Takayama, J. C. Reed, and K. Imai. 2001. Nuclear BAG-1 localization and the risk of recurrence after radiation therapy in laryngeal carcinomas. Cancer Lett. 165:103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang, X., G. Chernenko, Y. Hao, Z. Ding, M. M. Pater, A. Pater, and S. C. Tang. 1998. Human BAG-1/RAP46 protein is generated as four isoforms by alternative translation initiation and overexpressed in cancer cells. Oncogene 17:981-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang, X., Y. Hao, Z. Ding, and A. Pater. 2000. BAG-1 promotes apoptosis induced by N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide in human cervical carcinoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 256:491-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang, X., Y. Hao, A. Ferenczy, S. C. Tang, and A. Pater. 1999. Overexpression of anti-apoptotic gene BAG-1 in human cervical cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 247:200-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeiner, M., M. Gebauer, and U. Gehring. 1997. Mammalian protein RAP46: an interaction partner and modulator of 70 kDa heat shock proteins. EMBO J. 16:5483-5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zeiner, M., and U. Gehring. 1995. A protein that interacts with members of the nuclear hormone receptor family: identification and cDNA cloning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11465-11469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]