Abstract

Previous evaluations of inactivated whole-virus and envelope subunit vaccines to equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) have revealed a broad spectrum of efficacy ranging from highly type-specific protection to severe enhancement of viral replication and disease in experimentally immunized equids. Among experimental animal lentivirus vaccines, immunizations with live attenuated viral strains have proven most effective, but the vaccine efficacy has been shown to be highly dependent on the nature and severity of the vaccine virus attenuation. We describe here for the first time the characterization of an experimental attenuated proviral vaccine, EIAVUKΔS2, based on inactivation of the S2 accessory gene to down regulate in vivo replication without affecting in vitro growth properties. The results of these studies demonstrated that immunization with EIAVUKΔS2 elicited mature virus-specific immune responses by 6 months and that this vaccine immunity provided protection from disease and detectable infection by intravenous challenge with a reference virulent biological clone, EIAVPV. This level of protection was observed in each of the six experimental horses challenged with the reference virulent EIAVPV by using a low-dose multiple-exposure protocol (three administrations of 10 median horse infectious doses [HID50], intravenous) designed to mimic field exposures and in all three experimentally immunized ponies challenged intravenously with a single inoculation of 3,000 HID50. In contrast, naïve equids subjected to the low- or high-dose challenge develop a detectable infection of challenge virus and acute disease within several weeks. Thus, these data demonstrate that the EIAV S2 gene provides an optimal site for modification to achieve the necessary balance between attenuation to suppress virulence and replication potential to sufficiently drive host immune responses to produce vaccine immunity to viral exposure.

Development of effective vaccines to animal lentivirus infections is complicated by the diverse array of persistence mechanisms employed by these viruses to evade host immune surveillance and by the general lack of natural controlling immunity to lentiviral infections that typically result in progressively degenerative diseases. To date, the development of vaccines to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) has relied substantially on the use of animal lentivirus models to evaluate the efficacy of various vaccine strategies. Animal lentivirus systems used as AIDS vaccine models have included simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) for monkey, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) for monkey, equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) for horse, and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) for cat (1). The results of these experimental studies have yielded only limited success in identifying vaccines that can reproducibly elicit enduring broadly protective immunity against exposure to variant lentiviral populations. Interestingly, the greatest success has been realized with live attenuated animal lentivirus vaccines that are able to drive a critical maturation of virus-specific humoral and cellular immune responses (15, 24, 28). EIAV, a macrophage-tropic lentivirus, causes a persistent infection in horses and a chronic disseminated disease of worldwide importance in veterinary medicine (reviewed in reference 21). The disease, transmitted via blood-feeding insects or iatrogenic sources such as contaminated syringe needles, is characterized by recurring cycles of viremia and of clinical episodes characterized by fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, edema, and various wasting symptoms at irregular intervals separated by weeks or months. This chronic stage of disease typically lasts for 6 to 12 months postinfection, at which time most EIAV-infected horses progress to an inapparent state of infection without clinical signs (10, 21). Among virulent lentiviruses, EIAV is unique in that, despite aggressive virus replication and rapid antigenic variation, greater than 90% of infected animals progress from a chronic disease state to an inapparent carrier stage by establishing strict immunologic control over virus replication (21). Thus, the natural immunologic control characteristic of persistent EIAV infections offers a novel model for identifying critical immune correlates of protection and indicates the potential of developing an effective prophylactic vaccine to protect horses from EIAV exposure.

During the past 15 years, we have evaluated a number of experimental EIAV vaccines based on inactivated whole virus and on viral or recombinant envelope subunit vaccines. The results of these vaccine trials demonstrate a remarkable breadth of efficacy, ranging from protection from detectable infection or disease to severe enhancement of EIAV replication and disease. This indicates that vaccine immune responses are a double-edged sword that can have beneficial or deleterious effects on the outcome of virus exposure (8, 11, 14, 23, 25). In addition to our EIAV vaccine studies, Chinese scientists have reported success in controlling EIAV infections in that country with a live attenuated EIAV vaccine produced by serial passage in donkey leukocyte cells (27). However, the protective efficacy of this vaccine has not been confirmed by others, and the genetic and antigenic properties of the vaccine strain of virus are undefined. Thus, there remains an important need for the development of a well-characterized and effective vaccine to EIAV that can be applied to control this worldwide veterinary problem.

The rational approach to attenuated lentivirus vaccine development has been to inactivate selected accessory genes or regulatory segments to achieve a genetic composition that minimizes potential virulence but that supports sufficient sustained viral replication to achieve mature immune responses that are enduring and broadly protective. We previously reported that inactivation of expression of the accessory S2 gene of a reference pathogenic molecular clone designated EIAVUK resulted in a significant attenuation of virus replication levels and an asymptomatic infection in vivo without substantially altering viral replication in vitro in cultured equine macrophages (18, 19). This attenuated phenotype of the EIAVUKΔS2 proviral mutant appeared to offer a number of advantages as a molecularly characterized candidate to evaluate as a modified live vaccine to protect against virulent EIAV exposure. We describe here a comprehensive analysis of the virologic, immunogenic, and protective properties of the EIAVUKΔS2 in horses experimentally inoculated and challenged intravenously (i.v.) with single or multiple doses of the reference EIAVPV virulent strain of virus. The results of these studies indicate the potential of the EIAVUKΔS2 to elicit robust vaccine immunity and to protect against detectable infection by rigorous challenge virus exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of attenuated viral vaccine.

The EIAVUKΔS2 proviral clone was derived from the in vivo pathogenic molecular clone, EIAVUK (7), by inserting two stop codons in the S2 reading frame, as described (19). Viral stocks were prepared by harvesting the supernatant medium from Lipofectamine-mediated transfection (Gibco BRL) of equine dermal cells (ATCC CRL 6288) with EIAVUKΔS2 mutant proviral DNA (19). Viral stocks were assayed by a micro-reverse transcriptase (RT) assay, and stock viral titers were determined in an infectious center assay in fetal equine kidney cells, as described previously by Lichtenstein et al. (20).

Experimental subjects, clinical evaluation, and sample collection.

Eight outbred horses and three outbred ponies of mixed age and gender were used for two independent vaccine trials. All horses were clinically monitored daily and were maintained as described previously (9, 14). Rectal temperatures and clinical status were recorded daily. Samples of serum, plasma, and whole blood were collected from each horse at predetermined intervals. Plasma samples were collected at predetermined specified intervals and during each febrile episode (>39°C). Plasma samples were stored at −80°C until being used to determine plasma viral RNA level and to carry out genetic analysis of viral RNA. Tissue samples from the liver, spleen, and peripheral lymph nodes were collected from the horses for the genetic analysis of viral RNA to detect EIAV infection. Serum samples were stored at −20°C until being tested for antibody reactivity in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Western blot analysis, or neutralization antibody assays. Whole-blood samples were appropriately fractionated for enumeration of platelets or for experimentation with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). PBMC were either used on the same day for the evaluation of EIAV-specific proliferative responses and EIAV-specific cytolytic activity or were stored in liquid nitrogen for later evaluation.

Experimental immunization and virus challenge procedures. (i) Vaccine trial I.

We initially examined immunogenicity and protective efficacy of EIAVUKΔS2 in a group of six horses that were experimentally inoculated with the attenuated virus strain and were then challenged by using a low-dose multiple-exposure (LDME) challenge to more closely resemble natural exposure by horse fly bites. For this vaccine trial, the test horses were inoculated two times at a 30-day interval by i.v. injection of 105 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) of EIAVUKΔS2 vaccine stock, as titered by infectious center assay in fetal equine kidney cells (20). Six months following the initial vaccine dose, the six inoculated horses and two naïve horses were i.v. challenged by the LDME protocol, which consisted of three sequential i.v. inoculations of 10 median horse infectious doses (HID50) of the virulent challenge EIAVPV at 2-day intervals. The horses were monitored daily for clinical symptoms of EIA, and blood was drawn at regular intervals for assays of platelets, viral replication, and virus-specific immune responses (10, 14). The horses were observed for 328 days, at which time they were euthanatized and tissues from selected horses were harvested and processed for analyses of EIAV infection (12).

(ii) Vaccine trial II.

To extend the analyses of EIAVUKΔS2 vaccine efficacy by providing a more detailed analysis of tissue infection by challenge virus, we next employed our standard pony immunization and challenge system previously used to evaluate experimental inactivated whole-virus and subunit EIAV vaccines (8, 14, 25). Briefly, a group of three ponies were inoculated i.v. with 106 TCID50 of the same EIAVUKΔS2 vaccine stock utilized in the above vaccine trial. Six months after vaccination, all three vaccinated ponies were challenged i.v. with 3,000 HID50 of pathogenic EIAVPV. Inoculated ponies were monitored before and after challenge daily for clinical signs of EIAV, and blood was drawn at regular intervals for assays of platelets, levels of viral replication, and virus-specific immune responses (10, 14). The ponies were observed for 280 days, at which time they were euthanatized and selected tissues were harvested and processed for analyses of EIAV infection as described by Harrold et al. (12).

Quantitative and qualitative serologic analyses.

Serum immunoglobulin G antibody reactivity to EIAV envelope glycoproteins was quantitatively (endpoint titer) and qualitatively (avidity index and conformation ratio) determined by using our standard concanavalin A ELISA procedures as described previously (10). Virus-neutralizing activity to the challenge virus strain EIAVPV mediated by immune sera was assessed in an indirect cell-ELISA-based infectious center assay by using a constant amount of infectious EIAVPV and sequential twofold dilution of serum (9). Detection of serum antibody reactivity to EIAV core protein p26 was conducted by using the ViraCHEK/EIA kit manufactured by Synbiotics Laboratory (Via Frontera, San Diego, Calif.). Serum samples were also assayed in the present U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reference diagnostic assay for EIAV, i.e., the agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID) (3).

Quantification of virus RNA levels in plasma.

Plasma samples from all animals were analyzed for the presence of viral RNA per milliliter of plasma by using a previously described semiquantitative RT-PCR assay based on gag-specific amplification primers (10). The standard RNA curve was linear in the range of 102 molecules as a lower limit and 108 molecules as an upper limit.

Genetic strain analysis of viral RNA in plasma and tissue samples.

To differentiate vaccine strain EIAVUKΔS2 from the challenge virus EIAVPV, virion-associated genomic RNA was extracted from plasma samples and pulverized tissue samples as described earlier (12) and was then used for genetic analysis by a nested RT-PCR and restriction digestion analysis. To distinguish the parental challenge virus from the attenuated vaccine strain, we took advantage of the fact that the insertion of the two stop codons in the S2 reading frame generated a unique SpeI restriction digestion site not found in the parental S2 gene. Thus, a nested RT-PCR amplification spanning the parental-type S2 gene of the wild-type challenge virus EIAVPV produced a 5,820-bp fragment that is resistant to digestion by SpeI. In contrast, the analogous S2 fragment amplified from the vaccine strain EIAVUKΔS2 is susceptible to digestion by SpeI, generating characteristic 322- and 260-bp fragments resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. Primer oligonucleotides used for the nested RT-PCR included primer PV12AS for reverse transcription, primers S2F1 (5′GCAGTAGTAGTTAATGATGAA3′) and S2R1 (5′CAACCCTATATAATGTTGCTGTGGG3′) for the first round of amplification, and primers S40 and S15 for the nested reactions (17).

Assays of PBMC CTL activity.

EIAV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity of PBMC from inoculated and challenged animals was measured in a standard 51Cr release assay as described by Hammond et al. (9).

RESULTS

Clinical and virologic profiles of horses experimentally inoculated with EIAVUKΔS2.

We have previously demonstrated a correlation between a dynamic maturation of virus-specific immune responses and the development of protective immunity in monkeys experimentally inoculated with attenuated SIV strains, typically achieved by about 6 to 8 months postinoculation (2, 6, 22). In addition, Johnson et al. (15) demonstrated an inverse relationship between the degree of protection (vaccine efficacy) and the level of attenuation (vaccine safety) of experimental engineered SIV strains. This report demonstrated that the attenuated virus must sustain levels of viral replication sufficient to drive the maturation of immune responses to establish enduring broadly protective immunity. To assess the replication and virulence properties of EIAVUKΔS2, we inoculated a group of six horses i.v. with 106 TCID50 of the attenuated virus stock. The inoculated horses were monitored daily for any clinical signs of EIA (fever, petechiae, etc.), and blood samples were taken at regular intervals for measurement of platelets, plasma virus, and EIAV-specific humoral and cellular immunity.

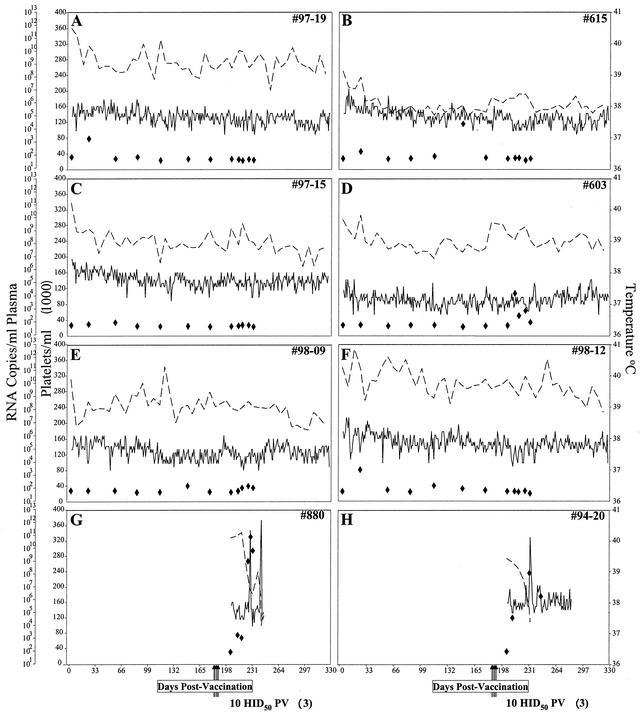

Figure 1A to F summarize the clinical and virologic profiles of the six experimentally inoculated horses over the 6-month observation period. In general, all of the experimentally immunized horses remained asymptomatic for EIA, as demonstrated by a lack of fever episodes and maintenance of normal levels of blood platelets, a sensitive quantitative measure of EIA (10, 26). This lack of detectable virulence by vaccination with EIAVUKΔS2 was associated with relatively low levels of virus replication (Fig. 1). The highest levels of EIAVUKΔS2 replication, approximately 103 genomic RNA copies per ml of plasma, were observed at about 3 weeks postinoculation, which corresponds to the typical timing for acute EIAV viremia (9, 26). Following this initial viral replication, EIAVUKΔS2 levels decreased to less than 100 genomic RNA copies per ml of plasma for the remainder of the observation period. The lack of disease and low levels of apparent systemic EIAVUKΔS2 replication observed here are in marked contrast to the clinical progression and levels of virus replication observed in animals experimentally infected with the parental virulent EIAVPV strain (Fig. 1G to H) (10, 16). In these latter infections, the first disease cycle is usually evident by 4 weeks postinfection, followed by sequential irregular disease cycles. In EIAVPV-infected animals, a minimum 107 RNA copies per ml of plasma are associated with EIA disease cycles and 104 to 105 copies per ml are typically observed during asymptomatic stages of infection. Thus, these data demonstrate the high level of attenuation caused by the inactivation of the viral S2 gene and the evident lack of virulence from persistent infection, as described previously in experimental infections of ponies (18).

FIG. 1.

Clinical and virologic profiles of experimental horses. Six horses (A to F) were vaccinated with EIAVUKΔS2 as described in Materials and Methods. Rectal temperature (—, right y axis) and platelet counts (· · ·, first left y axis) were monitored daily for up to 330 days (x axis) after vaccination. Quantification of the virus load (⧫, second left y axis) was performed on viral RNA extracted from plasma at periodic time points prior to and after virulent virus challenge by using the LDME protocol (↑↑↑), as described in Materials and Methods. Febrile episodes in the two control horses (G and H) subjected to LDME were defined by a rectal temperature above 39°C in conjunction with a reduction in platelets (below 100,000/μl of whole blood) and other clinical symptoms of EIA. EIAVUKΔS2-inoculated horses: (A) no. 97-19, (B) no. 615, (C) no. 97-15, (D) no. 603, (E) no. 99-09, and (F) no. 98-12. Control horses: (G) no. 880 and (H) no. 94-20.

Virulent EIAV challenge of horses experimentally inoculated with EIAVUKΔS2.

To examine the protective efficacy of the immune responses elicited by the attenuated virus infection, we next challenged the experimentally inoculated horses with a reference virulent EIAVPV strain used in previous vaccine trials (8, 11, 23, 25). The natural route of EIAV infection of horses in the field is by hematophagous insects that transmit microliters of blood from infected to naïve animals (13). To mimic this situation, we developed an LDME challenge that consists of a sequence of three i.v. inoculations of 10 HID50 of virulent EIAVPV administered at 2-day intervals. As summarized in Fig. 1G and H, challenge of two naïve horses with the LDME protocol resulted in acute EIA disease symptoms (fever and thrombocytopenia) by 3 weeks postchallenge, with a second disease cycle observed in horse no. 880 within 60 days postchallenge. These disease cycles were associated with viremia levels of greater than 108 RNA copies per ml of plasma. The clinical and virologic responses to the LDME challenge presented here are similar to those observed in at least six other experimentally infected horses that were part of other trials (data not shown) and are representative of the EIAVPV virulence in naïve horses (9, 10, 16).

The LDME challenge protocol was also used to examine protection provided by the EIAVUKΔS2-specific immune responses present in the six experimentally inoculated horses at 6 months postinfection. In marked contrast to the rapid disease observed in LDME-challenged control horses, the experimentally inoculated horses all remained asymptomatic over a 5-month observation period postchallenge. There were no significant increases in daily rectal temperatures or drop in platelet levels postchallenge (Fig. 1A to F). In addition, the levels of viremia postchallenge remained at about 100 RNA copies per ml of plasma during first 2 months postchallenge and never exceeded 1,000 copies per ml over the 5-month observation period postchallenge (Fig. 1). These data demonstrated that inoculation with the attenuated virus EIAVUKΔS2 elicited highly protective immunity from apparent disease and increases in viremia after virulent virus challenge.

Development of humoral and cellular immune responses to EIAVUKΔS2 immunization.

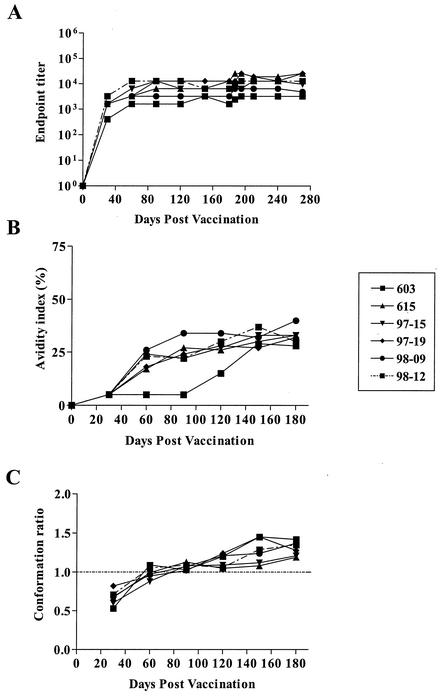

We next used our standard panel of quantitative (titer) and qualitative (avidity and conformation) assays to examine the maturation of EIAV envelope-specific antibody responses during the first 6 months postinoculation (Fig. 2). These data demonstrated a relatively uniform envelope-specific antibody response to the EIAVUKΔS2 inoculation among the six horses. Envelope-specific antibody titers increased rapidly during the first couple of months postinoculation, reaching steady-state levels that ranged from about 1:1,000 to 1:10,000 (Fig. 2A). In contrast to the rapid development of quantitative antibody levels, the qualitative properties of the envelope-specific antibodies, as measured by avidity and conformational dependence, increased for several more months, eventually reaching similar levels by 5 to 6 months postinoculation (Fig. 2B and C). The development of envelope-specific antibody responses to the attenuated virus, EIAVUKΔS2, is similar to the maturation of antibody responses characteristic of experimental infections with virulent EIAV, both in terms of the dynamics of change and the ultimate steady-state properties (9, 10).

FIG. 2.

Development of envelope-specific antibody responses to infection by inoculation by EIAVUKΔS2 and postchallenge. Longitudinal characterization of the quantitative and qualitative properties of induced EIAV envelope-specific antibodies were conducted in concanavalin A ELISAs of endpoint titer (A), avidity (B), and conformational dependence (C) as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Serum antibody titers for each time point are presented as the log10 of the highest reciprocal dilution yielding reactivity 2 standard deviations above background. (B) Avidity index measurements through day of challenge are presented as percentages of the antibody-antigen complexes resistant to disruption with 8 M urea. (C) Conformation dependence values through day of challenge are calculated as the ratio of serum antibody reactivity with native envelope to that with denatured envelope antigen. Conformation ratios greater than 1.0 indicate predominant antibody specificity for conformational determinants, while ratios less than 1.0 indicate predominant antibody specificity for linear envelope determinants.

A relatively slow development of serum-neutralizing antibodies to experimental EIAV infection that required several months in experimental infections with virulent and avirulent strains of EIAV, with average maximum titers of about 1:300, was previously reported (10). To examine the ability of the EIAVUKΔS2 inoculation to elicit serum-neutralizing antibodies, we tested immune serum samples taken at 6 months postinoculation for their ability to inactivate the parental virulent EIAVPV infectivity in cultured fetal equine kidney cells (9), as summarized in Fig. 3A. These data demonstrated that the attenuated virus infection generated serum antibody-neutralizing titers that ranged from 1:10 to 1:110 at 6 months postinoculation. In addition we assessed virus-specific CTL responses elicited by EIAVUKΔS2 6 months postinoculation by measuring EIAV Gag-specific reactivity of isolated PBMC in a standard CTL assay system (9). The Gag-specific CTL activity generated by the EIAVUKΔS2 is summarized in Fig. 3B. In general, the inoculated horses displayed similar levels of CTL activity, ranging from 25 to 40% specific lysis.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of humoral and cellular virus specific responses pre- and postchallenge in horses inoculated with EIAVUKΔS2. Characterization of EIAV-induced immune responses was illustrated in assays evaluating EIAV-specific neutralizing antibody response (A) and EIAV Gag-specific CTL activity (B). (A) Mean reciprocal dilutions of serum from vaccinated horses that neutralized 50% of input EIAVPV as measured in an infectious center assay are presented for serum samples collected at the day of challenge and 4 weeks postchallenge. (B) EIAV Gag-specific CTL activity elicited by experimental immunization and challenge was measured by using fresh PBMC from experimental horses at the day of challenge and 4 weeks postchallenge. EIAV Gag-specific CTL activity is presented as percent specific lysis of target cells. All procedures are described in detail by Hammond et al. (9).

Taken together, this panel of immune assays indicated the ability of EIAVUKΔS2 to achieve humoral and cellular immune responses by 6 months postimmunization that were similar to mature immunity observed in long-term inapparent carriers of EIAV, despite the relatively low levels of replication by the attenuated vaccine strain (10).

Commercially available diagnostic assays.

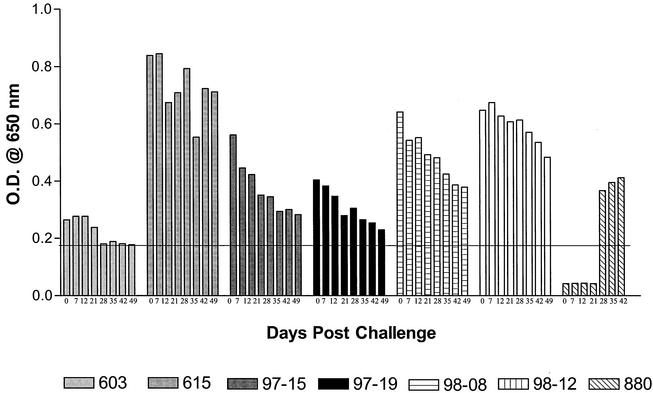

Immunogenicity of EIAVUKΔS2 was further characterized by reactivity testing in standard USDA-approved commercial diagnostic assays for EIAV infection based on detecting antibody to the viral capsid protein, p26. These diagnostic assays included the USDA AGID test (3) and the ELISA-based ViraCHEK. The data in Fig. 4 indicate that all six of the experimentally inoculated horses were seropositive in the ViraCHEK diagnostic assay at the day of challenge. In contrast, the same immune serum samples were uniformly negative in the less sensitive AGID tests (data not shown). These reactivities demonstrated that horses inoculated with the EIAVUKΔS2 can be detected by the more sensitive diagnostic assays that are the basis of USDA and other national regulatory policies to control EIAV infection, suggesting a need for diagnostics that can distinguish vaccinated from naturally infected horses.

FIG. 4.

Serologic responses of equids following challenge with EIAVPV. Antibodies against the core protein (p26) were examined by using the ViraCHEK ELISA. The horizontal line represents the optical density at 650 nm of the positive control antiserum supplied by the manufacturer. Values above this line are seropositive for EIAVPV.

Anamnestic immune responses to virulent virus challenge.

Infection by EIAV challenge of experimentally immunized horses is typically associated with detectable anamnestic immune responses that can be measured in the reference virus-specific antibody and CTL assays (9). Figures 2A, 3A, and 4 demonstrate a lack of detectable antibody anamnestic responses as measured, respectively, by quantitative changes in envelope-specific antibody, serum neutralization assays, and p26-specific antibody. In fact, interesting decreases in neutralizing antibody (Fig. 3A) and in p26-specific antibody (Fig. 4) in the experimentally inoculated horses after LDME challenge are in distinct contrast to the rapid rise in p26-specific antibodies observed in naïve control horses subjected to the same challenge. Similarly, Gag-specific CTL responses (Fig. 3B) declined by at least twofold at 4 weeks postchallenge in the five experimental horses that displayed detectable CTL activity as a result of EIAVUKΔS2 inoculation. The lack of detectable anamnestic responses to the LDME challenge suggests a very high level of immune control that either rigorously limits or prevents infection by the virulent challenge EIAVPV.

Detection of attenuated EIAVUKΔS2 and virulent EIAVPV strains.

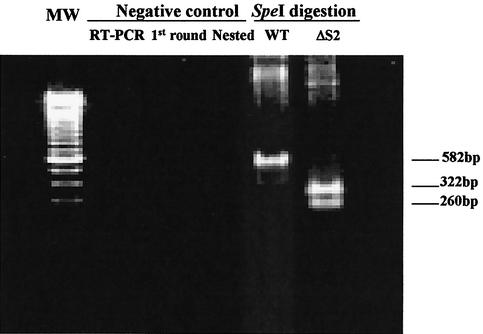

To provide a more sensitive and specific assay of infection by the challenge virus, we developed a nested RT-PCR procedure to distinguish between the parental S2 gene in the virulent challenge EIAVPV and the modified S2 gene in the attenuated EIAVUKΔS2 proviral strain (Materials and Methods). This diagnostic assay is based on the introduction of a unique SpeI restriction site in a 582-bp segment of the modified S2 gene that is not present in the wild-type S2 gene segment. As illustrated in Fig. 5, RT-PCR amplification of the S2 segment from EIAVPV genomic RNA produces a single 582-bp product that is resistant to digestion by SpeI. However, the RT-PCR amplification product from EIAVUKΔS2 is digested by SpeI into two smaller fragments (322 and 260 bp) that are clearly resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. The nested RT-PCR was highly specific and provided detection levels down to 20 RNA copies of S2.

FIG. 5.

Representative diagnostic RT-PCR/digest to distinguish attenuated and challenge EIAV strains. To distinguish modified from parental S2 genes contained in the attenuated and challenge virus, respectively, the region of the viral genome encompassing the S2 gene open reading frame was RT-PCR amplified from control RNA extracted from EIAVUK and EIAVUKΔS2 with virus-specific primers and was subjected to SpeI restriction endonuclease digestion and visualized by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining. MW, 100-bp molecular mass marker; WT, EIAVUK; and ΔS2, EIAVUKΔS2.

By using this diagnostic RT-PCR assay, we analyzed plasma samples taken from the challenged experimental and control horses at 4 and 17 weeks postchallenge and lymph nodes taken at 17 weeks postchallenge (Table 1). The wild-type S2 gene was readily detected in plasma and lymph node samples taken from the challenged control horses, consistent with the high levels of viral RNA in plasma detected in these horses after LDME challenge (Fig. 1). In contrast, the RT-PCR failed to detect either wild-type or modified S2 from five of the six experimental horses, reflecting the low levels of plasma viral RNA observed in these horses (Fig. 1). The modified S2 gene was detected only in horse no. 615 in the week-4 plasma and the lymph node sample taken at week 17. Wild-type S2, indicative of challenge virus infection, was not detected in any of the plasma or lymph node samples taken from the six experimental horses.

TABLE 1.

Genetic analysis of viral RNA in plasma and lymph node tissue in vaccinated and control horses challenged with EIAVPV

| Vaccine strain | Animal no. | Viral RNA in plasma at

|

Viral RNA in lymph node at wk 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 4 | Wk 17 | |||

| EIAVUKΔS2 | 603 | —a | — | — |

| 615 | ΔS2b | — | ΔS2 | |

| 97-15 | — | — | — | |

| 97-19 | — | — | — | |

| 98-09 | — | — | — | |

| 98-12 | — | — | — | |

| Unvaccinated | 97-20 | WTc | WT | WT |

| 880 | WT | N/Ad | N/A | |

—, negative, no amplification of viral RNA with expected size encompassing wild-type (wt) or mutated S2 gene.

ΔS2, amplification of viral RNA with expected size encompassing mutated S2 gene.

WT, amplification of viral RNA with expected size encompassing mutated WT gene.

N/A, sample not available.

Experimental challenge of ponies inoculated with EIAVUKΔS2.

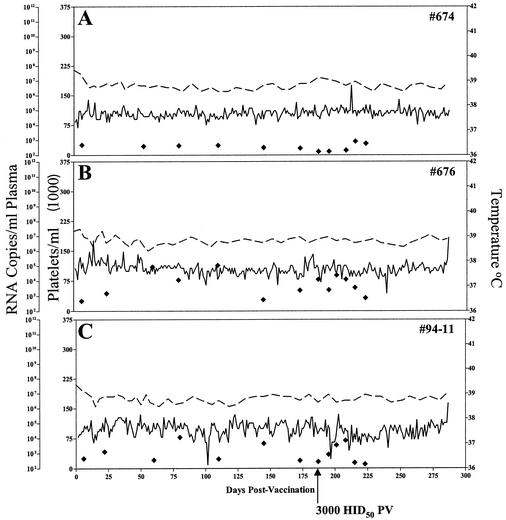

While the preceding genetic analysis indicated a lack of detectable infection by the challenge EIAVPV, the analyses are somewhat limited by the small number of tissue samples available for testing from the experimentally inoculated horses. Therefore, we performed a second experiment in three ponies to more directly address the issue of protection from infection after challenge. For this second experiment, we challenged a group of three ponies that were inoculated i.v. 6 months earlier with 106 TCID50 of the reference EIAVUKΔS2 stock. These experimental pony infections have been described in detail as part of the characterization of the in vivo role of S2 during persistent infection (18). As described previously, all of the experimentally infected ponies remained asymptomatic for EIA and maintained steady-state levels of EIAVUKΔS2 replication of about 103 RNA copies per ml of plasma (Fig. 6). A summary of the virus-specific antibody responses at 6 months postinoculation is presented in Table 2. In general, the antibody responses indicated a similar maturation of virus-specific immune responses to the experimental horse inoculations described above. These ponies then were used to test the protective efficacy of the immunity elicited by EIAVUKΔS2 to a more rigorous virus challenge consisting of 3,000 HID50 of EIAVPV inoculated i.v., a 100-fold increase over the total LDME exposure of 30 HID50. Figure 6 summarizes the clinical profiles of the three experimental ponies after the virulent virus challenge. These data indicate a lack of EIA clinical symptoms (fever and platelet reduction) during the 14-week postchallenge observation period. Therefore, the attenuated virus inoculation was able to protect against the development of detectable disease after i.v. inoculation of 3,000 HID50 of virulent EIAV.

FIG. 6.

Clinical and virologic profiles of experimental ponies inoculated with EIAVUKΔS2 and challenged with virulent EIAVPV. Ponies were inoculated i.v. with a single dose of EIAVUKΔS2 containing 3,000 equine HID50, as described in Materials and Methods. Rectal temperature (—, right y axis) and platelet count (…, first left y axis) were monitored daily for up to 280 days (x axis) after vaccination. Quantification of the virus load (⧫, second left y axis) was performed on viral RNA extracted from plasma at periodic time points prior to and after high-dose virus challenge (↑) (described in Materials and Methods). (A) Pony no. 674, (B) pony no. 676, and (C) pony no. 94-11.

TABLE 2.

Envelope-specific antibody responses at day of challenge in ponies experimentally inoculated with EIAVUKΔS2a

| Vaccine strain | Animal no. | Antibody endpoint titer | Antibody avidity index | Antibody conformation ratio | 50% neutralizing antibody titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIAVUKΔS2 | 674 | 1.3 × 104 | 53 | 1.2 | 0 |

| 676 | 1 × 105 | 48 | 1.5 | 6 | |

| 94-11 | 6.3 × 103 | 45 | 1.2 | 6 |

The quantitative and qualitative properties of envelope-specific serum antibody responses at 6 months postinoculation were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

To examine for any detectable infection by the challenge EIAVPV, we used the RT-PCR diagnostic protocol to assay for wild-type and modified S2 in plasma and tissues from the challenged ponies. Plasma samples were analyzed at weeks 1 through 4 and 14 postchallenge to assess acute and chronic infection status. The ponies were euthanatized at 14 weeks postchallenge, and samples of blood, lymph node, liver, and spleen were harvested and processed for the nested RT-PCR S2 diagnostic analysis. The results of these genetic assays (Table 3) revealed attenuated S2 in the majority of the plasma samples analyzed, with at least three positive samples for each pony; there was no detectable wild-type S2 in any plasma sample. Modified S2 was also detected in the lymph node and liver samples from pony no. 674 and in the spleen from pony no. 94-11. The remaining six of the nine tissue samples were negative for detectable S2, and no wild-type S2 was detected in any of the nine tissue samples. Thus, these data indicate that inoculation with EIAVUKΔS2 prevented detectable infection by rigorous i.v. challenge with 3,000 HID50 of highly virulent EIAVPV.

TABLE 3.

Genetic analysis of viral RNA in plasma and tissues in vaccinated horses challenged with EIAVPV

| Vaccine strain | Animal no. | Viral RNA in plasma at wk:

|

Viral RNA in tissues at wk 14

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 14 | Lymph node | Liver | Spleen | ||

| EIAVUKΔS2 | 674 | —a | ΔS2b | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | — |

| 676 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 94-11 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | ΔS2 | — | — | ΔS2 | |

—, no amplification of viral RNA with expected size encompassing wild-type (WT) or mutated S2 gene.

ΔS2, amplification of viral RNA with expected size encompassing mutated S2 gene.

DISCUSSION

The ideal goal of an AIDS vaccine is the production of enduring host immune responses that are able to protect against infection through natural routes of exposure by diverse strains of HIV-1. While these standards directed early vaccine development in human and animal lentivirus models, the nearly uniform lack of success in achieving this level of vaccine immunity by numerous and diverse vaccine strategies has generated doubt as to the feasibility of achieving apparently “sterilizing” immunity to lentiviral infections (1). These limitations have triggered reexamination of AIDS vaccine standards to consider experimental vaccine efficacy based more on the vaccine's ability postexposure to lower viral replication levels, to moderate clinical progression, and to reduce transmission potential. To define the specifics of these vaccine efficacy parameters, it is important to identify optimal vaccines in animal lentivirus models and associated immune correlates of protection that can be adapted to human vaccine trials.

Based on a wide variety of experimental vaccine studies in different lentivirus systems, it appears that classical viral particle or simple subunit vaccines fail to adequately drive host immune maturation to achieve enduring broadly protective virus-specific immune responses (22). Higher levels of success have been realized with various prime-boost vaccine regimens that combine live vector and protein subunit immunizations to achieve a level of immune maturation that can beneficially control virus replication and disease in experimentally challenged animals. The best levels of vaccine protection, however, have been realized with live attenuated viral vaccines, as demonstrated in the SHIV, SIV, and FIV systems. These attenuated animal lentiviral vaccine studies, however, have indicated an inverse relationship between the level of viral attenuation and the ability to achieve protection from experimental challenge (15). Thus, these live attenuated lentiviral vaccines provide an important model to evaluate the maximum level of vaccine efficacy in terms of duration and breadth of protection from variant virus strains and to define critical immune correlates of vaccine immunity.

In the EIAV system, we have previously demonstrated that classical vaccine strategies using viral particle or envelope subunit vaccines produce a marked spectrum of vaccine efficacy, ranging from highly strain-specific protection to severe enhancement of virus replication and disease (8, 11, 14, 23, 25). The present study for the first time demonstrates conclusively that an engineered live attenuated EIAV proviral vaccine is able to elicit protective immunity from disease and from detectable infection by rigorous i.v. virulent EIAV challenge. The vaccine protection was realized both against an LDME i.v. challenge (three administrations of 10 HID50) designed to mimic natural field infections and against a high-dose i.v. challenge containing 3,000 HID50 of virulent virus. While the protective efficacy of the present attenuated EIAV vaccine is similar to that observed with other successful attenuated animal lentivirus vaccines, the high-dose challenge employed in the EIAV vaccine trial is at least 300-fold higher than that employed for SIV, SHIV, and FIV vaccine studies. Vaccine protection from i.v. virus exposure has been found to be more difficult to achieve than is protection from mucosal virus challenge in various animal lentivirus systems (1, 29). Thus, the apparent efficacy of the attenuated EIAVUKΔS2 vaccine appears to document the feasibility of producing protective immunity against relatively strenuous viral exposure.

Does the EIAVUKΔS2 vaccine achieve sterilizing immunity? Vaccines typically limit viral infection to subclinical levels rather than completely preventing infection after virus exposure. While it is not possible to demonstrate with certainty a lack of infection by the challenge EIAV exposure, several lines of evidence are consistent with this possibility. First, there was a lack of humoral and cellular anamnestic responses in the immunized horses after viral challenge, indicating a lack of new infection to stimulate memory immune responses. In fact, the antibody and cellular immune responses actually decreased postchallenge. Second, there was no detectable increase in plasma virus levels postchallenge, as would be expected from infection by the aggressive EIAVPV challenge. Finally, we were unable to detect challenge virus S2 sequences by sensitive RT-PCR procedures in PBMC analyzed at several time points postchallenge and in various tissues analyzed at 5 months postchallenge. Taken together, these observations suggest that mature immune responses to the EIAVUKΔS2 inoculation may achieve sterilizing immunity to experimental virus challenge. However, more rigorous analyses of experimental horses postchallenge by blood transfers to naïve horses or immune suppression to amplify replication of infecting EIAV strains would substantiate the development of sterilizing immunity. The level of protection observed in the present studies certainly warrants further evaluation of this genetically defined provirus as a candidate vaccine to control EIAV infection.

The protective efficacy of the EIAVUKΔS2, however, must be considered since the EIAVPV challenge is a cell-free stock of a biological clone that contains a mixture of envelope quasispecies that are about 1% divergent from the attenuated proviral clone (7). Natural EIAV exposure, as with other lentiviruses, will include immunologically diverse viral strains and virus-infected cells contained in whole blood. The EIAVUKΔS2 vaccine provides a useful model system to test vaccine efficacy against challenge viruses with increasing levels of envelope diversity and against whole blood containing free virus and infected monocytes. The EIAVUKΔS2 vaccine described here also provides a useful system to evaluate potential immune correlates of protection. As observed in previously reported studies of attenuated SIV vaccines (2, 4-6, 22), it w2as found that there was a time requirement of about 6 months to achieve optimal protective immunity in horses experimentally inoculated with EIAVUKΔS2 (23); virus challenge at 2 months postinoculation of the attenuated EIAV resulted in 100% infection with the challenge virus (unpublished data). The development of protective immunity correlated with the maturation of EIAV envelope-specific antibody responses as measured by antibody titer, affinity, and conformational dependence. Interestingly, there was no obvious correlation of in vivo immune protection with the level of in vitro serum neutralization, as the EIAVUKΔS2 inoculation elicited neutralizing antibody titers to the challenge EIAVPV that ranged from less than 1:10 to 1:120. These observations suggest that the in vitro serum neutralization assays for EIAV may not accurately reflect the role of envelope-specific antibodies in vivo in light of the obvious importance of virus-specific antibody maturation to the development of protective immunity to virus challenge.

The protection realized with the EIAVUKΔS2 immunization further supports the hypothesis that vaccine immunity to lentivirus infection, including HIV-1, can be achieved despite the apparent lack of natural immunity. However, the experiments described here further emphasize the requirement for adequate maturation of virus-specific immune responses to achieve robust protective vaccine immunity. When the attenuated EIAV and other animal lentiviruses are used as models, it appears that the necessary immune maturation is best accomplished by sustained low levels of antigen presentation and consistent stimulation of the host immune system. In light of these observations, it appears that lentivirus vaccines will need to be based on regimens that require multiple antigen exposure and/or sustained antigen presentation, perhaps by live vector or DNA plasmid vaccines. Thus, it will be of interest to test these latter immunization strategies in the EIAV system to determine their efficacy compared to the standards set by the present live attenuated EIAV proviral vaccine.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID grant RO1 AI25850 (R.C.M.), by funds from the Lucille P. Markey Charitable Trust, and by the University of Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogers, W. M., C. Cheng-Mayer, and R. C. Montelaro. 2000. Developments in preclinical AIDS vaccine efficacy models. AIDS 14(Suppl. 3):S141-S151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clements, J. E., R. C. Montelaro, M. C. Zink, A. M. Amedee, S. Miller, A. M. Trichel, B. Jagerski, D. Hauer, L. N. Martin, R. P. Bohm, et al. 1995. Cross-protective immune responses induced in rhesus macaques by immunization with attenuated macrophage-tropic simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 69:2737-2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coggins, L., and N. L. Norcross. 1970. Immunodiffusion reaction in equine infectious anemia. Cornell Vet. 60:330-335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole, K. S., M. Murphey-Corb, O. Narayan, S. V. Joag, G. M. Shaw, and R. C. Montelaro. 1998. Common themes of antibody maturation to simian immunodeficiency virus, simian-human immunodeficiency virus, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. J. Virol. 72:7852-7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole, K. S., J. L. Rowles, B. A. Jagerski, M. Murphey-Corb, T. Unangst, J. E. Clements, J. Robinson, M. S. Wyand, R. C. Desrosiers, and R. C. Montelaro. 1997. Evolution of envelope-specific antibody responses in monkeys experimentally infected or immunized with simian immunodeficiency virus and its association with the development of protective immunity. J. Virol. 71:5069-5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole, K. S., J. L. Rowles, M. Murphey-Corb, J. E. Clements, J. Robinson, and R. C. Montelaro. 1997. A model for the maturation of protective antibody responses to SIV envelope proteins in experimentally immunized monkeys. J. Med. Primatol. 26:51-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook, R. F., C. Leroux, S. J. Cook, S. L. Berger, D. L. Lichtenstein, N. N. Ghabrial, R. C. Montelaro, and C. J. Issel. 1998. Development and characterization of an in vivo pathogenic molecular clone of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 72:1383-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond, S. A., S. J. Cook, L. D. Falo, Jr., C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1999. A particulate viral protein vaccine reduces viral load and delays progression to disease in immunized ponies challenged with equine infectious anemia virus. Virology 254:37-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond, S. A., S. J. Cook, D. L. Lichtenstein, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1997. Maturation of the cellular and humoral immune responses to persistent infection in horses by equine infectious anemia virus is a complex and lengthy process. J. Virol. 71:3840-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond, S. A., F. Li, B. M. McKeon, Sr., S. J. Cook, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 2000. Immune responses and viral replication in long-term inapparent carrier ponies inoculated with equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 74:5968-5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond, S. A., M. L. Raabe, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1999. Evaluation of antibody parameters as potential correlates of protection or enhancement by experimental vaccines to equine infectious anemia virus. Virology 262:416-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrold, S. M., S. J. Cook, R. F. Cook, K. E. Rushlow, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 2000. Tissue sites of persistent infection and active replication of equine infectious anemia virus during acute disease and asymptomatic infection in experimentally infected equids. J. Virol. 74:3112-3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issel, C. J., and L. D. Foil. 1984. Studies on equine infectious anemia virus transmission by insects. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 184:293-297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issel, C. J., D. W. Horohov, D. F. Lea, W. V. Adams, Jr., S. D. Hagius, J. M. McManus, A. C. Allison, and R. C. Montelaro. 1992. Efficacy of inactivated whole-virus and subunit vaccines in preventing infection and disease caused by equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 66:3398-3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, R. P., J. D. Lifson, S. C. Czajak, K. S. Cole, K. H. Manson, R. Glickman, J. Yang, D. C. Montefiori, R. Montelaro, M. S. Wyand, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1999. Highly attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus protect against vaginal challenge: inverse relationship of degree of protection with level of attenuation. J. Virol. 73:4952-4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leroux, C., J. K. Craigo, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 2001. Equine infectious anemia virus genomic evolution in progressor and nonprogressor ponies. J. Virol. 75:4570-4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leroux, C., C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1997. Novel and dynamic evolution of equine infectious anemia virus genomic quasispecies associated with sequential disease cycles in an experimentally infected pony. J. Virol. 71:9627-9639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, F., C. Leroux, J. K. Craigo, S. J. Cook, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 2000. The S2 gene of equine infectious anemia virus is a highly conserved determinant of viral replication and virulence properties in experimentally infected ponies. J. Virol. 74:573-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, F., B. A. Puffer, and R. C. Montelaro. 1998. The S2 gene of equine infectious anemia virus is dispensable for viral replication in vitro. J. Virol. 72:8344-8348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lichtenstein, D. L., K. E. Rushlow, R. F. Cook, M. L. Raabe, C. J. Swardson, G. J. Kociba, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1995. Replication in vitro and in vivo of an equine infectious anemia virus mutant deficient in dUTPase activity. J. Virol. 69:2881-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montelaro, R., J. M. Ball, and K. Rushlow. 1993. Equine retroviruses, p. 257-360. In J. A. Levy (ed.), Τhe Retroviridae. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 22.Montelaro, R. C., K. S. Cole, and S. A. Hammond. 1998. Maturation of immune responses to lentivirus infection: implications for AIDS vaccine development. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14(Suppl. 3):S255-S259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montelaro, R. C., C. Grund, M. Raabe, B. Woodson, R. F. Cook, S. Cook, and C. J. Issel. 1996. Characterization of protective and enhancing immune responses to equine infectious anemia virus resulting from experimental vaccines. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:413-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson, C., B. Makitalo, R. Thorstensson, S. Norley, D. Binninger-Schinzel, M. Cranage, E. Rud, G. Biberfeld, and P. Putkonen. 1998. Live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)mac in macaques can induce protection against mucosal infection with SIVsm. AIDS 12:2261-2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raabe, M. L., C. J. Issel, S. J. Cook, R. F. Cook, B. Woodson, and R. C. Montelaro. 1998. Immunization with a recombinant envelope protein (rgp90) of EIAV produces a spectrum of vaccine efficacy ranging from lack of clinical disease to severe enhancement. Virology 245:151-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rwambo, P. M., C. J. Issel, W. V. Adams, Jr., K. A. Hussain, M. Miller, and R. C. Montelaro. 1990. Equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) humoral responses of recipient ponies and antigenic variation during persistent infection. Arch. Virol. 111:199-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen, R.-X., and Z. Wang. 1985. Development and use of an equine infectious anemia donkey leucocyte attenuated vaccine. EIAV: a national review of policies, programs, and future objectives. American Quarter Horse Association, Amarillo, Tex.

- 28.Ui, M., T. Kuwata, T. Igarashi, K. Ibuki, Y. Miyazaki, I. L. Kozyrev, Y. Enose, T. Shimada, H. Uesaka, H. Yamamoto, T. Miura, and M. Hayami. 1999. Protection of macaques against a SHIV with a homologous HIV-1 Env and a pathogenic SHIV-89.6P with a heterologous Env by vaccination with multiple gene-deleted SHIVs. Virology 265:252-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren, J. 2002. Preclinical AIDS vaccine research: survey of SIV, SHIV, and HIV challenge studies in vaccinated nonhuman primates. J. Med. Primatol. 31:237-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]