Abstract

In the present studies we developed lentivirus vectors with regulated, consistent transgene expression in B lymphocytes by incorporating the immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer (Eμ) with and without associated matrix attachment regions (EμMAR) into lentivirus vectors. Incorporation of these fragments upstream of phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) or cytomegalovirus promoters resulted in a two- to threefold increase in enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in B-lymphoid but not T-lymphoid, myeloid, fibroblast, or carcinoma cell lines. A 1-log increase in EGFP expression was observed in B-lymphoid cells (but not myeloid cells) differentiated from human CD34+ progenitors in vitro transduced with Eμ- and EμMAR-containing lentivectors. Lastly, we evaluated the expression from the EμMAR element in mice 2 to 24 weeks posttransplant with transduced hematopoietic stem cells. In mice receiving vectors with the Eμ and EμMAR elements upstream of the PGK promoter, there was a 2- to 10-fold increase in EGFP expression in B cells (but not other cell types). Evaluation of the coefficient of variation of expression among different cell types demonstrated that consistent, position-independent transgene expression was observed exclusively in B cells transduced with the EμMAR-containing vector and not other cells types or vectors. Proviral genomes with the EμMAR element had increased chromatin accessibility, which likely contributed to the position independence of expression in B lymphocytes. In summary, incorporation of the EμMAR element in lentivirus vectors resulted in enhanced, position-independent expression in primary B lymphocytes. These vectors provide a useful tool for the study of B-lymphocyte biology and the development of gene therapy for disorders affecting B lymphocytes, such as immune deficiencies.

Genetically modified human hematopoietic stem cells may offer new treatment options for patients with inherited or acquired genetic disorders by producing and delivering therapeutic gene products in vivo. Two components of successful gene therapy with hematopoietic stem cells are the efficient transfer of genes to the target cells and the appropriate expression of the transgene in desired cell populations. Retrovirus vectors have commonly been used to transfer therapeutic genes into target cells because they can stably integrate into the target cell genome at relatively high efficiency. Gene transfer to primitive human hematopoietic progenitors in clinical trials with patients with immune deficiencies has recently been demonstrated using retrovirus vectors with transgenes expressed from strong, constitutive promoters (3, 7).

While constitutive transgene expression is suitable for gene therapy applications in deficiencies of housekeeping genes, such as lysosomal storage disease or other enzyme deficiencies, it will not be acceptable for other disorders. For example, X-linked agammaglobulinemia results from a deficiency in Bruton's tyrosine kinase, which is involved in signal transduction pathways necessary for B-cell development (23). Ectopic or otherwise nonregulated expression of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in all cell progeny of hematopoietic stem cells could lead to abnormalities in cell growth or function (21, 23).

In gene therapy applications requiring lineage-restricted transgene expression, a self-inactivating vector design in which the viral promoter and enhancer in the U3 region of the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) are removed from the vector plasmid, which eliminates the proviral promoter following proviral integration, can be used (26, 32). The transgene is then expressed from an internal lineage-specific promoter and/or other regulatory elements. One advantage to the use of lentivirus-based gene transfer vectors is that large genomic regulatory regions including promoters and/or enhancers can be incorporated into the vector without destabilizing the viral genome, thus providing lineage-specific expression. This strategy has resulted in lineage-specific transgene expression in erythroid cells (24, 25), T-lymphoid cells (19, 22), and antigen-presenting cells (11). In general, regulated expression has been demonstrated most effectively in erythroid cells for which the elements controlling several erythroid-specific genes are well characterized (13). However, to date, consistent, regulated, and position-independent transgene expression in B lymphocytes has not been demonstrated from lentivirus gene transfer vectors.

Lentivirus vectors integrate randomly into the genome and, thus, proviral transgene expression is affected by the local chromosomal environment into which the vector has integrated through the effects of local chromosomal structure, activators, repressors, or silencers. This can result in variable levels of transgene expression from each integration site. Furthermore, the proportion of cells expressing the transgene can be variable within a clone, which is termed positional variegation of expression. In theory, altering the chromatin structure to more closely resemble a genomic locus transcriptionally active in the desired lineage will lead to consistency in the regulation and level of transgene expression.

To achieve B-lymphoid-specific expression of germ line transgenes, many studies have included regulatory elements from the immunoglobulin locus, such as the heavy chain intronic enhancer (Eμ) (5, 17, 29). Incorporation of the Eμ element in expression cassettes can lead to B-lymphoid enhancement of transgene expression in cell lines and transgenic mice (1); however, the level of enhancement may be variable (10, 16). To achieve consistent, position-independent B-lymphoid-specific expression in transgenic mice, the matrix attachment regions (MARs), which flank Eμ sequences in the heavy chain locus, must be included within the expression cassette (10, 16). Deletion of the MARs at the endogenous immunoglobulin gene also results in variegated expression in B lymphocytes (30). There are several mechanisms by which the MARs likely influence transgene expression. For example, there are binding sites for transcription factors such as Bright (B-cell regulator of immunoglobulin heavy chain transcription) (18), which enhances expression in activated or terminally differentiated B lymphocytes. The MARs also contain binding sites for elements which prevent expression in non-B lymphocytes, such as SATB1, which represses expression in T lymphocytes (12). The MARs can also affect expression through effects on the organization and structure of chromatin domains (4), maintenance of a domain of chromatin accessibility (20), and enhancing histone acetylation (14).

In the studies presented here, we have investigated the ability of Eμ and EμMAR elements to produce consistent, position-independent transgene expression from lentivirus vectors in B-lymphoid cell lines and primary cells. Our studies demonstrate that incorporation of the EμMAR element into lentivirus gene transfer vectors resulted in regulated, position-independent transgene expression in B lymphocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of cell lines.

All cell lines were maintained in optimal growth medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin (all base media, l-glutamine, and antibiotics were obtained from Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, Calif.), and fetal bovine serum (FBS; Omega Scientific, Tarzana, Calif.) or heat-inactivated calf serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). B-lymphoid (Nalm-6, Reh, Raji, and AA2), T-lymphoid (Jurkat and CEM), and myeloid cell lines (U937, HL60, and K562) were maintained in RPMI with 10% FBS (R10). Adherent HEK 293 and NIH 3T3 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS and 10% heat-inactivated calf serum, respectively.

Lentivirus vectors and supernatant production.

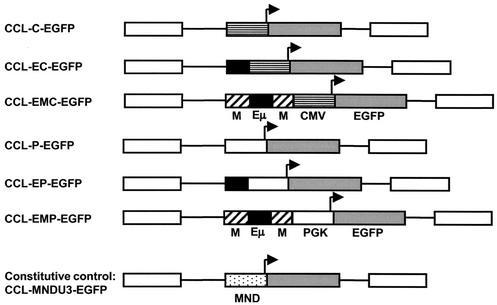

The lentivirus vectors used in this study were based on the pCCL self-inactivating vector kindly provided by Luigi Naldini (CellGenesys, Foster City, Calif.) (32). In this vector, the viral promoter was crippled through the deletion of the viral enhancers and TATA box in the U3 promoter region of the 3′LTR. Two basic vector designs were used with the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter transgene expressed from either an internal murine phosphoglycerate kinase promoter (PGK; CCL-P-EGFP) or human cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter (CMV; CCL-C-EGFP) (Fig. 1). The genomic Eμ enhancer, or EμMAR element, was cloned upstream of each promoter. In one set of vectors, a 0.6-kb fragment containing the core Eμ (kindly provided by Sherri Morrison, University of California Los Angeles) was cloned upstream of the PGK promoter (CCL-EP-EGFP) in the forward orientation and upstream of the CMV promoter in both orientations (CCL-EforC-EGFP and CCL-ErevC-EGFP). In the second set of vectors, a larger 0.9-kb fragment from the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus which includes Eμ and its flanking MARs (EμMAR; kindly provided by Marc Shulman, University of Toronto) was inserted upstream of the PGK and CMV promoters (CCL-EMP-EGFP and CCL-EMC-EGFP). A lentivector with the constitutive promoter from the U3 region of the MND retrovirus (9), which was modified from the myeloproliferative sarcoma virus retroviral LTR (CCL-MNDU3-EGFP), was used as a positive control in these studies.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagrams of integrated proviruses used in this study. The vectors are third-generation self-inactivating vector backbones based on a CCL series of vectors (26). Abbreviations: C, human CMV promoter; P, murine phosphoglycerate promoter; E, immunoglobulin intronic heavy chain enhancer; EM, immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer with associated MARs; MNDU3, LTR promoter for the U3 region of MND retrovirus.

Vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G)-pseudotyped lentivirus supernatants were produced by triple transfection of 293T fibroblasts as described elsewhere. In brief, 10 μg of the vector plasmid, 10 μg of the 8.9 packaging plasmid (27) (which does not express human immunodeficiency virus type 1 accessory proteins) and 2 μg of pMDG-VSV-G envelope plasmid were transfected into confluent HEK 293T cells (10-cm-diameter dish). Supernatant was collected from 48 to 96 h posttransfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. The titer of each batch of supernatant was determined following exposure of subconfluent 293A cells to serial dilutions of virus supernatant supplemented with 8 μg of Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml. Three days after exposure to supernatant, the percentage of cells expressing provirus was determined by flow cytometric analysis for EGFP expression. The number of infectious virus particles per milliliter was calculated by multiplying the percentage of 293 cells expressing EGFP, the number cells at the time of virus addition, and the supernatant dilution.

Cell line transduction.

To facilitate evaluation of expression in cells with a single copy of vector, aliquots of cells were transduced with a series of half-log serial dilutions of each supernatant. Cells were transduced by the addition of diluted supernatant to aliquots of 105 cells in a total volume of 1 ml. The proportion of cells expressing EGFP was determined by flow cytometry 5 to 7 days later with detailed expression analysis performed on cells transduced by the supernatant dilution that yielded less than 10% positive cells.

Human cord blood progenitor transduction and differentiation.

Human umbilical cord blood samples were collected in accordance with the Committee on Clinical Investigations of Childrens Hospital Los Angeles in anticoagulant citrate-dextran (Sigma). The mononuclear cells were collected following Ficoll-Paque density gradient separation (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway N.J.) and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The CD34+ cells were separated using a CD34 progenitor isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.) and either used immediately or viably cryopreserved until use. For lentivirus transduction, the CD34-positive cells were cultured overnight at a density of 2 × 105/ml on Retronectin (Takara Shuzo Inc., Otsu, Japan) in X-vivo 15 (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) with 50 ng of human interleukin 6 (hIL-6; Biosource International Inc., Camarillo, Calif.) per ml, 20 ng of hIL-3 (Biosource International)/ml, 50 ng of human stem cell factor (hSCF; Biosource International)/ml, and 50 ng of human FLT3L (Immunex Inc., Seattle, Wash.)/ml. On the following day, virus supernatant was added twice to a final concentration of 2 × 107/ml (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 100). On the subsequent day, the cells were harvested and washed in PBS. Half of the cells were plated under culture conditions which support B lymphopoiesis on S17 stroma in RPMI with 5% FBS and 50 ng of FLT3L/ml as previously described (15). The remaining cells were cultured under myeloid conditions on Retronectin in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (I-MDM) supplemented with 20% FBS, 10 ng of hIL-3/ml, 25 ng of hIL-6/ml, and 25 ng of hSCF/ml. Both B-lymphoid and myeloid cultures were maintained by half-volume medium changes twice weekly.

Murine marrow harvest, transduction, and transplantation.

The mice used in this study were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and maintained at the Childrens Hospital Los Angeles Central Animal Facility as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Donor marrow was harvested from 8- to 12-week-old male B6.SJL mice (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ; stock number 002014; Jackson Laboratories) 2 days post-5-fluorouracil injection (150 mg/kg of body weight; American Pharmaceutical Partners, Los Angeles, Calif.). The marrow was cultured at a density of 2 × 106/ml on Retronectin-coated tissue culture plates in I-MDM supplemented with 20% FBS, 10 ng of murine IL-3/ml, 2.5 ng of murine SCF/ml (all murine cytokines were from Biosource International), 50 ng of hIL-6/ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, and 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol. Lentivirus supernatant was added once daily on days 1 and 2 to achieve a final virus concentration of 107/ml with each transduction (MOI, ∼5). Recipient 8- to 12-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (stock number 664; Jackson Laboratories) were conditioned by two doses of 600 cGy of γ-irradiation (128 cGy/min, from a cesium-137 source) given on two consecutive days (total of 1,200 cGy). One to 2 h following the second dose of irradiation, 2 × 106 to 4 × 106 transduced donor marrow cells were injected into each recipient in 200 μl of PBS with 50 U of heparin/ml. Antibiotics were added to the drinking water for 3 weeks posttransplantation (200 μg of Maxim-200/ml; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, St. Joseph, Mo.). The donor-recipient pairs were major histocompatibility complex matched but congenic at the non-major histocompatibility CD45 locus, with donors expressing CD45.1 and recipients expressing CD45.2 isoforms of CD45, which are easily distinguishable using commercially available antibodies (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.).

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting.

For flow cytometry analysis of EGFP transgene expression in cell lines, cells were harvested, washed in PBS, and resuspended in indicator-free Hanks' buffered saline (Invitrogen). The samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). For intracellular staining for the immunoglobulin heavy chain (μ), cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit according to the manufacturer's standard protocol (Becton Dickinson) and stained with a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human immunoglobulin M (heavy chain) antibody (Pharmingen).

Differentiated progeny of transduced human cord blood CD34+ progenitors were analyzed at 5 weeks of culture by flow cytometric analysis for EGFP expression. To evaluate EGFP expression in B lymphocytes, cells were harvested from the S17 cultures and stained with PE-conjugated anti-human CD19 antibodies (Pharmingen). Expression in myeloid cells was evaluated in all cells produced in the myeloid cultures, since B lymphocytes are not produced or maintained under these conditions (15).

In murine transplant experiments, donor engraftment and transgene expression was monitored simultaneously by flow cytometric analysis for PE-conjugated anti-CD45.1 antibody staining (Pharmingen) for donor cells (recipient cells express CD45.2) and EGFP transgene expression. At 1 to 2 months posttransplant, peripheral blood was collected from the tail vein in heparinized glass capillary tubes to evaluate donor engraftment and EGFP expression. At the time of sacrifice, peripheral blood, marrow, spleen, and thymus were collected for flow cytometric analysis of transgene expression. For analysis of transgene expression in specific hematopoietic lineages, single-cell suspensions were labeled with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD45.1 antibodies and PE-conjugated lineage markers and subjected to simultaneous three-color flow cytometric analysis. The PE-conjugated lineage markers were directed against CD19 or B220 for B lymphocytes, CD4 and CD8 for T lymphocytes, TER-119 for erythrocytes, GR-1 for granulocytes, and CD11b for monocytes and macrophages (all antibodies from Pharmingen). For transgene expression analysis of leukocytes, cell suspensions from blood, marrow, and spleen were treated with FACSLyse solution (Becton Dickinson), which contains 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) to lyse erythrocytes and fix samples prior to flow cytometric analysis. In some experiments, a fixative-free ammonium chloride erythrocyte lysis buffer was used, which prevented leakage of EGFP.

To develop EGFP-positive pools of cells with single vector integrations, aliquots of cells were transduced with a series of half-log serial dilutions of each supernatant. The proportion of cells expressing EGFP was determined by flow cytometry 5 days later, and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed on the population of cells with between 2 and 5% positive cells. The cells were sorted on a FACSVantage cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using CellQuest software. EGFP-positive cells were collected in RPMI with 20% FBS and cultured as described above.

Vector copy number analysis.

The vector copy number was determined by real-time PCR analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Puregene genomic DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer's recommended protocols (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). EGFP sequences were amplified using a 200 nM concentration each of a sense primer (5′-CTGCTGCCCGACAACCA-3′) and an antisense primer (5′-GAACTCCAGCAGGACCATGTG-3′). Each PCR amplification reaction was performed with 100 ng of genomic DNA in Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Incorporated, Foster City, Calif.). Amplified EGFP sequences were detected with 50 nMprobe (5′-6-carboxyfluorescein-CCCTGAGCAAAGACCCCAACGAGA-tetramethylrhodamine-3′), which is homologous to EGFP sequences internal to the primers. Samples and standards were run in duplicate. Each PCR run included a standard curve of genomic DNA with known EGFP copy numbers of 1, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001 vector copies per cell. PCR amplification was performed in an Applied Biosystems GeneAmp 7700 sequence detection system instrument with denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification with denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing and extension at 60°C for 60 s. Analysis was performed using the Sequence Detection software (version 0.1.7).

Restriction endonuclease sensitivity assay.

For the preparation of nuclei, cultured cells were harvested, washed in PBS, and pelleted by centrifugation (200 × g). The cell pellets were resuspended in cell lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM sodium chloride, 3 mM magnesium chloride, and 0.4% NP-40) and washed three times in cell lysis buffer. After the last wash, the cells were resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer. The restriction enzyme NruI (10 U; Invitrogen) was added to each sample and then incubated at 37°C. NruI was used because it cuts once in the provirus, in the leader region. At the specified time of incubation (4 or 16 h), the enzyme was inactivated by heating at 65°C for 15 min and the DNA was collected following phenol-chloroform extraction. The samples were then digested with BglII (Invitrogen), which cuts in both proviral LTRs and thus cuts out the provirus. Following digestion, the DNA samples were run on agarose gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (NEN/Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.). The membranes were hybridized to an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled EGFP probe that detects the provirus.

RESULTS

Eμ enhances expression in B-lymphocyte cell lines.

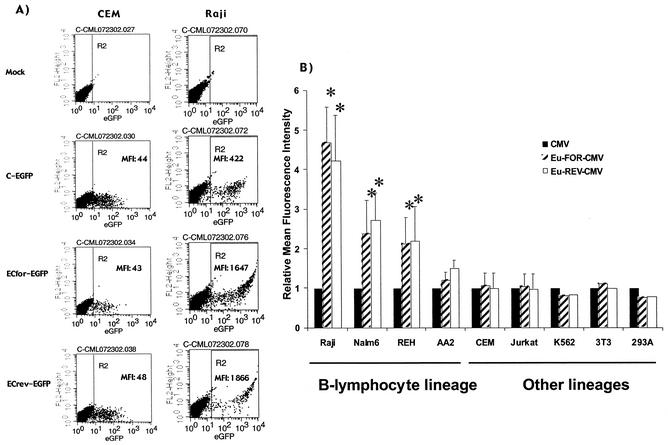

In the first series of experiments, we evaluated the effect of the Eμ element and its orientation in lentivirus vectors on EGFP reporter transgene expression driven by the human CMV promoter in a series of B-lymphoid and non-B-lymphoid cell lines (Fig. 1, vectors CCL-C-EGFP and CCL-EC-EGFP). Multiple or variable numbers of proviral integrants may obscure or confound differences in transgene expression from different vectors. Thus, to evaluate expression in cells containing a single vector integrant, we exposed various cell lines to serial dilutions of lentivirus supernatant. Within a cell line, comparisons of expression levels by vectors were performed on the cells transduced with vector dilutions with similar levels of gene transfer and less than 10% EGFP-positive cells. There was a wide range in the level of transgene expression, measured as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), from the control CCL-C-EGFP vector in the various cell types. Since different cell lines express variable levels of EGFP from the vectors with the base CMV promoter, the data are presented as the relative MFI, in which the MFI from the Eμ-containing vectors is divided by the MFI of the CMV vector for the same cell type, thereby giving a fold enhancement of expression.

In B-lymphoid cell lines there was a 1.2- to 4.7-fold-higher MFI of EGFP expression from vectors carrying the Eμ element in either the forward or reverse orientation compared to the vector lacking the Eμ element, demonstrating an orientation-independent increase in transgene expression (Fig. 2). Sample flow cytometric analyses used in this experiment to calculate data from CEM T-lymphoid cells and Raji B-lymphoid cells are shown in Fig. 2A. The increased expression in B lymphocytes from the Eμ element was statistically significant (Student's t test) in three of four cell lines (P < 0.05), Raji, Nalm-6, and REH, and insignificant in one cell line, AA2 (P < 0.1). In contrast to the increased expression in B-lymphoid cells, the Eμ element did not increase the MFI of EGFP expression in non-B-lymphoid cells such as 293A or NIH 3T3 fibroblasts, CEM or Jurkat T-lymphoid cells, or K562 myeloid cells (Fig. 2B) (P > 0.2; Student's t test). These data demonstrate that the Eμ element provides an orientation-independent increase in the level of expression in B-lymphoid cells but not other cell types.

FIG. 2.

Enhancement of transgene expression by Eμ is B-lymphoid specific and orientation independent. Cells were transduced once with half-log dilutions of lentivirus supernatant and evaluated by flow cytometry 5 to 7 days later. The aliquot of each cell type with each vector with <10% positive cells was used for the graph to minimize the effects of multiple integrations. (A) Sample flow cytometric dot plots used for the analysis in this figure. (B) A summary of the flow cytometric analysis of EGFP expression. The data are presented as the fold enhancement over the MFI of CMV-promoted vectors ± the standard deviation. The * indicates a statistically significant increase of expression over the CCL-C-EGFP control with a P value of <0.05 (Student's t test).

Enhancement with Eμ and EμMAR elements is physiologically regulated in vitro.

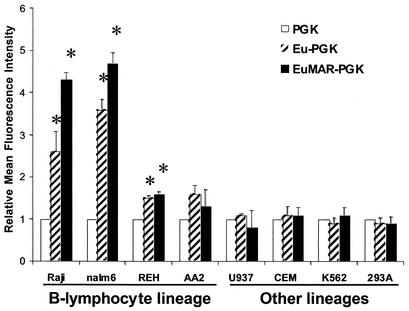

In transgenic mouse studies, expression cassettes carrying the Eμ enhancer showed an increase in the level of transgene expression in B lymphocytes; however, the expression levels were variable even among B lymphocytes (1). Inclusion of the MARs, which flank the Eμ enhancer in the transgenic cassette, produced consistent, B-lymphoid-specific, and position-independent transgene expression (16). To determine the effects of the Eμ MARs in lentivirus vectors, we analyzed the levels of EGFP expression from vectors carrying either the Eμ or EμMAR elements in B-lymphoid and non-B-lymphoid cell lines.

Incorporation of either the Eμ element or the EμMAR element into the lentivirus vectors with either the PGK or CMV promoters resulted in a marked increase in the MFI in B-lymphoid cell lines compared to the parental vectors. Averages of the MFIs from two independent experiments are presented in Fig. 3. In Nalm-6 and Raji, for example, the highest levels of expression were observed from the CCL-EMP-EGFP vector (with the EμMAR), with intermediate expression from the CCL-EP-EGFP vector (with the Eμ) and the lowest from CCL-P-EGFP. In REH and AA2, overall lower levels of enhancement were observed with similar levels of expression from CCL-EP-EGFP and CCL-EMP-EGFP. The increased level of expression for the CCL-EP-EGFP and CCL-EMP-EGFP vectors was significantly higher than expression from the control CCL-P-EGFP in Nalm-6, RAJI, and REH (P < 0.05; t test). In AA2 cells, expression from the CCL-EMP-EGFP was significantly higher than the control (P < 0.05), while expression from the CCL-EP-EGFP vector was not statistically higher than that of the control CCL-P-EGFP (P = 0.1; t test).

FIG. 3.

Transgene expression from the PGK promoter is enhanced in B-lymphoid cell lines with the Eμ or EμMAR elements. Cells were transduced once with half-log dilutions of lentivirus supernatant and evaluated by flow cytometry 5 to 7 days later. The aliquot of each cell type with each vector with <10% positive cells was used for the graph to minimize the effects of multiple integrations. The data are presented as the average fold enhancement over the MFI of PGK-promoted vectors from two experiments. The * indicates a statistically significant increase of expression over the CCL-P-EGFP control vector with a P value of <0.05 (Student's t test).

There was not an increase in the level of transgene expression in any of the non-B-lymphoid cell lines tested from vectors carrying either Eμ or EμMAR elements over the parental PGK (Fig. 3). Similar results were observed with the CMV-promoted vectors (data not shown). The enhancement of transgene expression from the Eμ and EμMAR vectors in the B-cell lines was stably maintained for up to 8 months of extended in vitro passage of the B cells (data not shown).

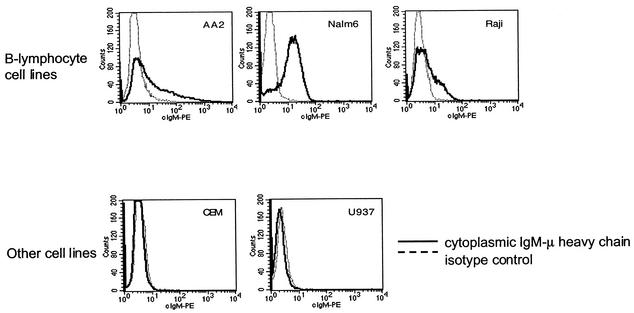

The level of enhancement varied among the B-lymphoid cell lines, with the highest expression observed in Raji and Nalm-6 and lower enhancement observed in REH and AA2. We investigated whether the level of enhancement of transgene expression from the Eμ- and EμMAR-containing vectors correlated with the expression of the endogenous μ heavy chain gene expression. During B-cell development, the μ heavy chain is first expressed in the cytoplasm in pre-B-cells following DH-VH rearrangement and on the cell surface in immature B cells following light chain rearrangement. The levels of μ heavy chain expression were determined in the cytoplasm following permeabilization by staining with a PE-conjugated anti-human μ-immunoglobulin heavy chain antibody and flow cytometric analysis. The level of cytoplasmic μ heavy chain expression and the level of transgene enhancement from the Eμ and EμMAR elements were similar (Fig. 4). For example, endogenous μ expression was detected in Nalm-6, AA2, and Raji cells, which demonstrated enhancement of EGFP transgene expression from the Eμ- and EμMAR-containing vectors. As expected, the μ-immunoglobulin heavy chain was not expressed in myeloid cells (U937) and T lymphocytes (CEM). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the enhancement of expression from Eμ- and EμMAR-containing proviruses is B-lymphoid specific, and the level of expression is physiologically regulated similarly to the endogenous immunoglobulin heavy chain gene.

FIG. 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of cytoplasmic expression of the endogenous immunoglobulin heavy chain gene in hematopoietic cell lines. The cells were permeabilized prior to antibody staining to detect cytoplasmic μ expression.

Expression in human B lymphocytes differentiated in vitro.

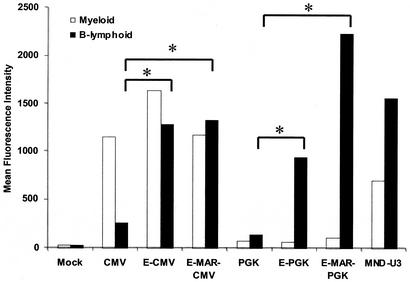

In the next experiments we evaluated the expression from lentivectors carrying Eμ and EμMAR in normal primary human B-lymphoid and myeloid cells differentiated from transduced progenitor cells. Human cord blood CD34+ cells were transduced with the CMV- and PGK-promoted lentivirus vector series and then differentiated into B-lymphoid and myeloid cells using in vitro cell culture systems that direct lineage-specific differentiation. The CMV promoter was highly active in the myeloid cells, with high levels of EGFP expressed (MFIs, 1,150 to 1,637) from the vectors with the CMV promoter alone or with the Eμ-CMV or EμMAR-CMV elements (Fig. 5). B lymphocytes expressed relatively low levels of EGFP from the CMV parental vector (MFI, 260). However, addition of the Eμ or EμMAR elements to the CMV promoter dramatically increased the expression in B lymphocytes to levels similar to that in myeloid cells, with MFIs of 1,288 and 1,327, respectively. Thus, expression from the CCL-EC-EGFP and CCL-EMC-EGFP vectors demonstrated a high level of transgene expression in both myeloid and B-lymphoid cells.

FIG. 5.

Transgene expression in hematopoietic cells differentiated from lentivirally transduced human cord blood CD34+ cells. The CD34+ cells were exposed to lentivirus supernatant, and then one aliquot was cultured under myeloid differentiation conditions and a second aliquot was cultured under B-lymphoid differentiation conditions. To determine EGFP expression in B lymphocytes, the cells were stained with antibodies against CD19 in the B-lymphoid cultures, while expression in myeloid cells was determined by flow cytometry for EGFP expression in all cells of myeloid cultures. The * indicates that the increased expression observed from vectors containing the Eμ or EμMAR elements was statistically higher than that with either control vector (P < 0.05).

Transgene expression from the PGK-promoted vector CCL-P-EGFP was lower in both myeloid and B-lymphoid cells (MFIs of 75 and 141, respectively) than from the CMV-promoted vectors (Fig. 5). Incorporation of the Eμ or EμMAR elements into the PGK-promoted vector led to marked increases in transgene expression in B-lymphoid cells (MFIs of 939 and 2,238, respectively). The increased expression observed from vectors containing the Eμ or EμMAR elements with both promoters was statistically significant (P < 0.05). There was no increase in the level of EGFP expression in myeloid cells by the vectors with either the Eμ enhancer or the EμMAR elements with either promoter (P > 0.1).

This experiment demonstrates the potential of the Eμ and EμMAR elements to enhance expression specifically in normal primary human B lymphocytes in vitro.

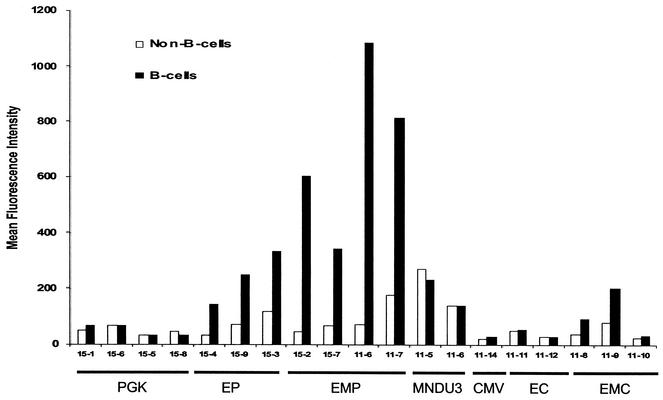

EμMAR stimulates expression in B lymphocytes in murine cells in vivo.

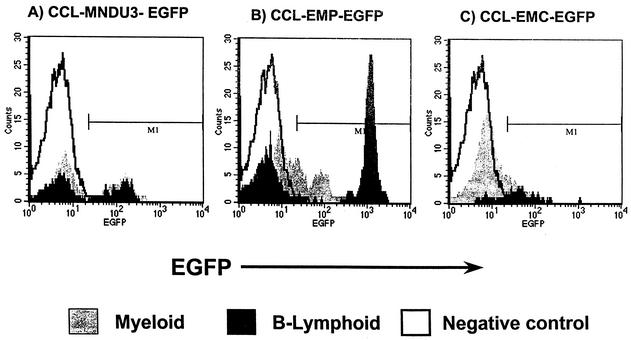

Expression analysis in cell lines and normal human B lymphocytes derived from CD34+ cord blood progenitor cells indicated that both the Eμ and EμMAR elements enhanced expression in B lymphocytes and that this enhancement was stable during the 5-week culture in vitro. In the next series of experiments, we investigated the effects of the Eμ and EμMAR elements on transgene expression in primary hematopoietic cells produced in vivo from transduced murine hematopoietic stem cells. Lentiviruses randomly insert their genetic material into the target cell genome, and thus proviral transgene expression may be influenced by the local chromosomal environment into which the vector has integrated. We hypothesized that both the Eμ and the EμMAR fragments would provide enhanced B-lymphocyte expression but that the EμMAR fragment would also provide consistent and position-independent B-lymphoid expression. To test this hypothesis, donor murine marrow was exposed to lentivirus supernatant under conditions which transduce ∼10% of the progenitors with a low or single vector integrant in each cell. The transduced marrow was transplanted into lethally irradiated murine recipients. Peripheral blood samples were collected 5 to 8 weeks posttransplant by tail vein sampling and analyzed for EGFP transgene expression by flow cytometric analysis in B220+ or CD19+ B lymphocytes and in B220− or CD19− cells (hereafter referred to as non-B cells). A sample histogram analysis from three recipients is shown in Fig. 6, and a summary of the EGFP expression in B lymphocytes and non-B lymphocytes from all recipients is shown in Fig. 7.

FIG. 6.

Representative flow cytometry analysis of EGFP transgene expression in peripheral blood from mice at 8 weeks posttransplant. (A) Control mouse recipient of marrow transduced with the CCL-MNDU3-EGFP vector. (B) Recipient of marrow transduced with the CCL-EMP-EGFP vector. (C) Recipient of marrow transduced with the CCL-EMC-EGFP vector.

FIG. 7.

Summary of EGFP transgene expression in murine peripheral blood at 5 to 8 weeks posttransplant. B lymphocytes were detected by positive staining for B220 or CD19. Non-B lymphocytes were all leukocytes negative for B220 or CD19.

In recipients of the PGK series of vectors, the parental CCL-P-EGFP vector showed low levels of expression in both B lymphocytes and non-B lymphocytes (Fig. 7). Statistically higher MFIs were observed in circulating B lymphocytes from recipients of CCL-EP-EGFP (P < 0.05) and CCL-EMP-EGFP (P < 0.05) than of the parental CCL-P-EGFP vector, whereas there was not increased expression in non-B cells (P > 0.1) (Fig. 7). Overall, the level of expression in B lymphocytes was threefold higher from the vector with the EμMAR element (average MFI, 714; range of MFIs, 344 to 1,089) than from the vector with only the Eμ element (average MFI, 245; range of MFIs, 146 to 336). A relatively high level of expression was observed in both B-lymphocyte and non-B-lymphocyte cell types in recipients of the constitutive positive control lentivector CCL-MND-EGFP (Fig. 6 and 7), indicating that there is not a biological block to efficient EGFP transgene expression in non-B-lymphoid cells.

At the time of recipient sacrifice (8 to 15 weeks posttransplantation), spleens were harvested for analysis of transgene expression and vector copy number in B lymphocytes. A low level of expression was observed in B lymphocytes from the CCL-P-EGFP vector (MFIs, 29 to 30) (Table 1). As observed with the peripheral blood samples, incorporation of the Eμ element resulted in a 1.6- to 2.4-fold increase in the MFI of EGFP expression (MFIs, 46 to 72) in B lymphocytes (Table 1). Transgene expression from the CCL-EMP-EGFP vector was further increased, with MFIs of 156 to 299, a 5.2- to 10-fold increase in the MFI over that of the parental PGK vector (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of transgene expression and proviral copy number analysis in recipient spleens

| Vector | MFI of B lympho- cytes | Proportion of cells expressing EGFPa | Provirus copy no.b | Ratio of cells expressing EGFP/vector copy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGK | 30 | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0.5 |

| PGK | 29 | 0.013 | 0.024 | 0.54 |

| PGK | 30 | 0.016 | 0.0052 | 0.31 |

| Eμ-PGK | 72 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.93 |

| Eμ-PGK | 47 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.63 |

| Eμ-PGK | 46 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.33 |

| EμMAR-PGK | 299 | 0.039 | 0.050 | 0.78 |

| EμMAR-PGK | 171 | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.42 |

| EμMAR-PGK | 156 | 0.106 | 0.157 | 0.68 |

| CMV | NAc | 0 | NDd | |

| CMV | NA | 0 | 0.025 | 0 |

| EμMAR-CMV | 89 | 0.01 | 1.290 | 7.8 × 10−3 |

| EμMAR-CMV | 31 | 0.007 | 0.825 | 8.4 × 10−3 |

| Negative control mouse | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Proportion of cells expressing EGFP was determined by flow cytometry analysis.

Determined by real-time PCR.

NA, not available, as cells were not expressing EGFP.

ND, sample not analyzed.

To verify that the higher level of expression in the Eμ- and EμMAR-containing vectors was not from increased vector proviral copies per cell, we calculated the proportion of cells expressing EGFP per proviral copy as determined by real-time quantitative PCR analysis on DNA samples from the spleens of recipient mice (Table 1). The proportion of cells carrying the provirus that expressed EGFP was not consistently different among recipients of the different vectors. For example, in samples from mice transplanted with PGK-transduced cells, 0.31 to 0.54 cells were expressing EGFP per vector copy. Recipients of EμPGK- and EμMAR-PGK-containing vectors expressed EGFP in 0.33 to 0.93 and 0.42 to 0.78 cells per vector copy, respectively. These data indicate that there was a similar proportion of cells expressing EGFP per vector copy for each vector and that the higher expression from the Eμ and EμMAR vectors in B lymphocytes was not due to higher vector copy numbers but was due to intrinsic differences in the expression from each vector.

Neither Eμ nor EμMAR stimulate expression from the CMV promoter in murine cells.

In contrast to transgene expression from the PGK series of vectors, low levels of expression in low proportions of cells were observed in B lymphocytes and non-B cells in the recipients of the CMV series of vectors. Surprisingly, the EμMAR element did not increase the level of expression from the CMV promoter in B lymphocytes (Fig. 6 and 7). The lack of expression was not due to a lack of gene transfer, since proviral sequences were detected in spleens of mice transplanted with CMV-promoted vectors at similar levels to those observed with PGK-promoted vectors (Table 1). The reason for the lack of expression from the CMV promoter in this study is unclear; however, it is of note that other studies have also observed that the human CMV promoter is poorly expressed in murine cells (2, 28).

The EμMAR element contributes to position-independent transgene expression.

In addition to increasing the level of expression, we investigated whether the EμMAR element increased the uniformity or position independence of transgene expression in B-lymphocyte and non-B-lymphocyte cell types.

A uniform level of expression was observed in B lymphocytes from the CCL-EMP-EGFP vector, evidenced by the sharp peak in the level of EGFP expression in B lymphocytes (Fig. 6B). The variation in the level of EGFP expression among the cells in a sample can be quantified by the coefficient of variation (COV), which is calculated during routine data analysis in the CellQuest software. A low COV indicates a uniform level and position independence of expression.

A comparison of the COV of EGFP expression in B-lymphoid and non-B-lymphoid cells from peripheral blood samples from mice transplanted with marrow transduced with the CCL-EP-EGFP and CCL-EMP-EGFP vectors and the control CCL-MND-EGFP vector is presented in Table 2. In each recipient of the CCL-EMP-EGFP vector, there was a ∼2-fold-higher COV for non-B lymphocytes than for B lymphocytes. This represents a significantly wider variation in the level of expression from the CCL-EMP-EGFP vector in non-B cells than in B cells (P < 0.005; paired t test). This difference cannot be attributed to general expression differences between B-lymphoid and non-B-lymphoid expression, as there was not a statistical difference between the COVs observed in B cells and non-B cells from the CCL-EP-EGFP (P = 0.23; paired t test) or CCL-MNDU3-EGFP (P = 0.25; paired t test) vectors. These data demonstrate that the MAR elements flanking Eμ are necessary for position-independent, transgene expression from lentivirus vectors in B lymphocytes in vivo.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the COV of the MFI of EGFP expression in circulating cells

| Vector | Animal | MFI COV

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| B cells | Non-B cells | ||

| EμMAR-PGK | 11-6 | 39 | 67 |

| 11-7 | 59 | 83 | |

| 15-2 | 30 | 56 | |

| 15-7 | 35 | 77 | |

| Eμ-PGK | 15-4 | 95 | 77 |

| 15-5 | 70 | 85 | |

| 15-8 | 89 | 48 | |

| MND | 11-4 | 122 | 64 |

| 11-5 | 68 | 68 | |

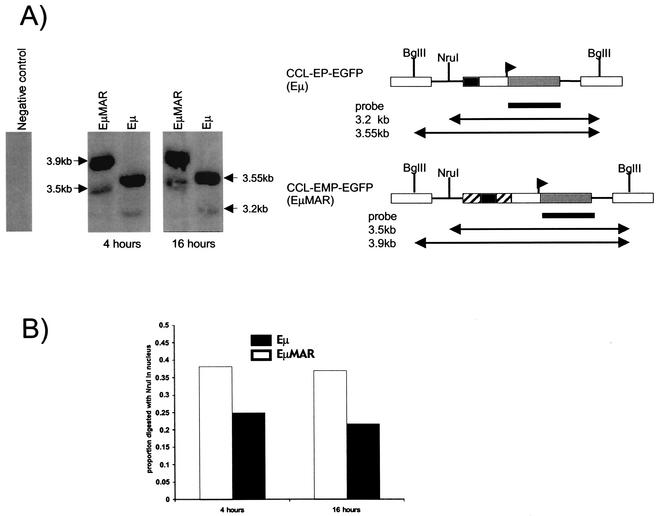

The EμMAR element increases the endonuclease sensitivity of the proviral genome.

We next determined whether the MAR element contributed to accessibility of the proviral chromatin. To obtain pools of cells with ∼1 copy per cell, we used FACS analysis to sort EGFP-positive cells from CEM-, K562-, and Nalm-6-transduced pools with less than 5% EGFP-positive cells. Nuclei were harvested from cells carrying the CCL-EP-EGFP and CCL-EMP-EGFP vectors and control untransduced cells. To determine the accessibility of the proviral chromatin in cells transduced with each vector, DNA in chromatin from intact, isolated nuclei was digested with NruI, which cuts once in the proviral genome, upstream of the EμMAR element. Subsequently, the genomic DNA was extracted and the provirus was cut out of the genome using BglII. Southern blot analysis was performed, and the proportion of the proviral genome that was in chromatin accessible to digestion with the restriction endonuclease (NruI) was quantified by densitometry. The Southern blot autoradiograph and a summary of the CEM densitometry data for one experiment are presented in Fig. 8A. Densitometric analysis of the Southern blot autoradiographs in CEM cells is summarized in Fig. 8B and demonstrated there was a 1.5- to 2.0-fold increase in the level of NruI digestion in nuclei from cells carrying proviruses with the EμMAR element over that of those with the Eμ. In Nalm-6 and K562 cells, the same trend was present, with a 1.1- to 1.5-fold increased NruI digestion of vector proviruses carrying the EμMAR element over that in those carrying the Eμ element alone (data not shown). Collectively, these data demonstrate increased chromatin accessibility of proviruses carrying the MAR element over those without it.

FIG. 8.

Restriction endonuclease sensitivity of proviruses. (A) Schematic diagram of the predicted fragments following NruI digestion of the nuclei and subsequent BglII digestion of extracted DNA on cells transduced with either vector. Sample autoradiograph of CEM cells following endonuclease restriction and Southern blot hybridization to an EGFP-labeled probe. (B) Summary of the densitometry analysis from the Southern blot autoradiograph shown in panel B.

DISCUSSION

Consistent, position-independent transgene expression will be necessary for effective, enduring gene therapies of single gene disorders. Most gene therapy clinical trials directed to hematopoietic stem cells to date, including the two trials demonstrating therapeutic benefit for severe combined immune deficiency (3, 7), have utilized the constitutive retroviral LTR promoter for transgene expression. However, long-term animal studies have indicated that, over time, transgene expression can be silenced from viral promoters (6, 8). Furthermore, lineage-specific regulation of expression will also be required for some disorders affecting cells of a single lineage (e.g., hemoglobinopathies, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, chronic granulomatous disease). We reasoned that incorporation into a gene transfer vector of genomic regulatory sequences, such as enhancers and MARs from a cellular gene expressed in a lineage of interest, would provide regulated, position-independent expression in the lineage of interest.

We tested this hypothesis by evaluating transgene expression in cells of the B-lymphoid lineage from integrated lentivirus vectors containing the enhancer from the μ-immunoglobulin heavy chain gene, which is expressed exclusively in B cells. The Eμ enhancer was the first lineage-specific cellular enhancer to be described (5, 17), and it has routinely been used to drive expression of germ line transgenes to the B-lymphoid lineage in transgenic mice (10, 16). The Eμ enhancer binds and is activated by several transcriptional factors present in cells of the B-lymphoid lineage, such as Bright (18). The Eμ enhancer is flanked by MAR elements which are essential for consistent, position-independent expression of transgenes under control of the Eμ enhancer. Transgene expression cassettes lacking the MAR display variable levels of expression in individual transgenic founders and are subject to silencing (10, 16). In contrast, transgenes containing the MAR sequences flanking the Eμ enhancer display consistent levels of expression among different founder mice, and the chromatin associated with the MAR-containing transgenes remains in an open configuration (16). Ideally, the presence of the Eμ enhancer and associated MAR sequences in lentivirus vectors would have similar effects of increasing expression levels specifically in B lymphocytes and decreasing the variability of expression from vectors integrated at different chromosomal sites.

In the first set of experiments, we evaluated the expression profile of lentivirus vectors with and without the Eμ enhancer element. These studies demonstrated that the Eμ element enhances expression from lentivirus vectors in B-lymphoid cells from a variety of sources, including cell lines, normal human cells in vitro, and primary murine cells in vivo. The enhancement is B-cell specific and is independent of the orientation of the Eμ element in the lentivirus vector, as would be expected of an enhancer. These expression data from integrated lentivirus vector proviruses are similar to the expression observed from expression cassettes containing the Eμ enhancer in transient expression assays and transgenic mice (16). As expected, expression levels from the exogenous Eμ enhancer in the lentivirus vectors paralleled that of the endogenous Eμ immunoglobulin heavy chain gene, with the highest expression of the EGFP transgene seen in the B-cell lines with the highest levels of expression of cytoplasmic μ heavy chain protein. Normal human B lymphocytes differentiated from CD34+ progenitors on S17 stromal cells express cytoplasmic μ heavy chain at 5 weeks (15). Transcriptional factors which activate the Eμ enhancer, such as Bright, increase in amounts with increasing stages of B-cell maturation, thereby activating both the exogenous and endogenous Eμ elements (31). Thus, these vectors display the desired property of physiologically responsive, lineage-specific expression.

Utilizing the weak, basal murine PGK promoter with a low intrinsic level of transgene expression, we achieved relatively B-lymphoid-specific expression in normal human and primary murine hematopoietic cells. In contrast, by coupling the Eμ enhancer with the strong, constitutive human CMV promoter, which expresses at high levels in myeloid cells but expresses poorly in B cells, we obtained a high level of expression in both human myeloid and B-lymphoid cells. The poor expression from the human CMV promoter in human B-lymphoid cells, which is strongly improved by the presence of the Eμ enhancer, suggests that the intrinsic enhancer of the human CMV promoter fragment is not active in B cells but that the CMV promoter can function when activated by the Eμ enhancer. In contrast, the human CMV promoter was inactive in murine cells of all lineages and was not activated in B cells by the presence of the Eμ enhancer. Other studies have also demonstrated poor expression from the human CMV promoter in murine tissues (2, 28). Murine cells may lack trans-acting factors needed for transcription from the human CMV promoter, and this apparently cannot be overcome by the inclusion of the Eμ enhancer even though the Eμ enhancer can function in murine B cells, based on the enhancement of expression observed with the PGK promoter.

Recombinant lentivirus vectors integrate into random sites of the target cell genome. Thus, expression from integrated lentivirus vectors may be influenced by transcriptional enhancers or silencers or other elements in the local chromatin environment, leading to inconsistent or variable expression from each integration site. In studies of transgenic mice, position-independent expression in the B-lymphoid lineage from expression cassettes with the Eμ enhancer was only observed if the MARs which flank the Eμ enhancer were included in the vector (16). We evaluated the uniformity of transgene expression from integrated proviruses by comparing the COV of the level of EGFP expression from circulating murine B-lymphoid and non-B-lymphoid cells transduced with vectors with and without the Eμ and EμMAR elements. Lower COVs were observed in B lymphocytes than in non-B cells in recipients of the EμMAR-PGK vector. Higher COVs were observed in B lymphocytes expressing from the Eμ-PGK and MND vectors, which do not contain the MAR element. These data demonstrate that the EμMAR element is necessary for uniform, position-independent B-lymphoid transgene expression from lentivirus vectors.

Transgenic mouse studies by Jenuwein and colleagues have suggested that the EμMAR element maintained the chromatin in an open configuration (20) and thereby accessible to transcriptional machinery. We investigated whether the MAR element contributed to position-independent transgene expression by maintaining the chromatin in an open configuration in integrated lentiviral proviruses using a restriction endonuclease sensitivity assay. The data from these experiments demonstrated that cells carrying the MAR element had increased chromatin accessibility in intact nuclei over otherwise similar vectors without the MAR element. This effect was observed in CEM, K562, and Nalm-6 cells, which are derived from the T-lymphocyte, myeloid, and B-lymphocyte lineages, respectively, even though expression enhancement was only observed from Nalm-6. These data demonstrate that expression of the transgene is not necessary to maintain the provirus in an open configuration. This is similar to the observations of Jenuwein and colleagues in transgenic mouse studies, where they determined that transgene transcription was not necessary for accessibility in chromatin (20).

In summary, incorporation of the Eμ or EμMAR elements in lentivirus vectors resulted in enhanced transgene expression in human and murine B-cell lines and primary cells over that in control vectors without these elements. Addition of the EμMAR element with the CMV promoter resulted in an equalization of transgene expression between human B-lymphoid and myeloid cells. Furthermore, consistent, position-independent transgene B-lymphoid expression was observed from integrated lentiproviruses expressing from the PGK promoter with the EμMAR element in primary murine cells differentiated from transduced progenitors. Our data suggest that the mechanism of this enhancement is due, at least in part, to the maintenance of the proviral genome in an open configuration. It is likely that the chromatin-opening function of the MAR element will contribute to consistent transgene expression in B lymphocytes from other promoters as well. The development of these vectors will facilitate the development of models of B-lymphoid disease and therapy by directing expression of genes involved in B-cell malignancies and the development of directed, lineage-specific gene therapy for immune deficiencies, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Health and Human Services (PO1 CA59318). C.L. was supported by fellowships from the Immune Deficiency Foundation and Childrens Hospital Los Angeles Research Institute.

We thank Karen Pepper for excellent technical support, Gay Crooks for assistance with B-lymphocyte cultures, and Marc Shulman and Sheri Morrison for plasmids containing the Eμ and EμMAR elements used in these studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, J. M., A. W. Harris, C. A. Pinkert, L. M. Corcoran, W. S. Alexander, S. Cory, R. D. Palmiter, and R. L. Brinster. 1985. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature 318:533-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addison, C. L., M. Hitt, D. Kunsken, and F. L. Graham. 1997. Comparison of the human versus murine cytomegalovirus immediate early gene promoters for transgene expression by adenoviral vectors. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1653-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiuti, A., S. Slavin, M. Aker, F. Ficara, S. Deola, A. Mortellaro, S. Morecki, G. Andolfi, A. Tabucchi, F. Carlucci, E. Marinello, F. Cattaneo, S. Vai, P. Servida, R. Miniero, M. G. Roncarolo, and C. Bordignon. 2002. Correction of ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy combined with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Science 296:2410-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez, J. D., D. H. Yasui, H. Niida, T. Joh, D. Y. Loh, and T. Kohwi-Shigematsu. 2000. The MAR-binding protein SATB1 orchestrates temporal and spatial expression of multiple genes during T-cell development. Genes Dev. 14:521-535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerji, J., L. Olson, and W. Schaffner. 1983. A lymphocyte-specific cellular enhancer is located downstream of the joining region in immunoglobulin heavy chain genes. Cell 33:729-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowtell, D. D., G. R. Johnson, A. Kelso, and S. Cory. 1987. Expression of genes transferred to haemopoietic stem cells by recombinant retroviruses. Mol. Biol. Med. 4:229-250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavazzana-Calvo, M., S. Hacein-Bey, G. de Saint Basile, F. Gross, E. Yvon, P. Nusbaum, F. Selz, C. Hue, S. Certain, J. L. Casanova, P. Bousso, F. L. Deist, and A. Fischer. 2000. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science 288:669-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Challita, P. M., and D. B. Kohn. 1994. Lack of expression from a retroviral vector after transduction of murine hematopoietic stem cells is associated with methylation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2567-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Challita, P. M., D. Skelton, A. el-Khoueiry, X. J. Yu, K. Weinberg, and D. B. Kohn. 1995. Multiple modifications in cis elements of the long terminal repeat of retroviral vectors lead to increased expression and decreased DNA methylation in embryonic carcinoma cells. J. Virol. 69:748-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockerill, P. N., M. H. Yuen, and W. T. Garrard. 1987. The enhancer of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus is flanked by presumptive chromosomal loop anchorage elements. J. Biol. Chem. 262:5394-5397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui, Y., J. Golob, E. Kelleher, Z. Ye, D. Pardoll, and L. Cheng. 2002. Targeting transgene expression to antigen-presenting cells derived from lentivirus-transduced engrafting human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood 99:399-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson, L. A., T. Joh, Y. Kohwi, and T. Kohwi-Shigematsu. 1992. A tissue-specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell 70:631-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis, J., and D. Pannell. 2001. The beta-globin locus control region versus gene therapy vectors: a struggle for expression. Clin. Genet. 59:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez, L. A., M. Winkler, and R. Grosschedl. 2001. Matrix attachment region-dependent function of the immunoglobulin mu enhancer involves histone acetylation at a distance without changes in enhancer occupancy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:196-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fluckiger, A. C., E. Sanz, M. Garcia-Lloret, T. Su, Q. L. Hao, R. Kato, S. Quan, A. de la Hera, G. M. Crooks, O. N. Witte, and D. J. Rawlings. 1998. In vitro reconstitution of human B-cell ontogeny: from CD34+ multipotent progenitors to Ig-secreting cells. Blood 92:4509-4520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrester, W. C., C. van Genderen, T. Jenuwein, and R. Grosschedl. 1994. Dependence of enhancer-mediated transcription of the immunoglobulin mu gene on nuclear matrix attachment regions. Science 265:1221-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillies, S. D., S. L. Morrison, V. T. Oi, and S. Tonegawa. 1983. A tissue-specific transcription enhancer element is located in the major intron of a rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain gene. Cell 33:717-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrscher, R. F., M. H. Kaplan, D. L. Lelsz, C. Das, R. Scheuermann, and P. W. Tucker. 1995. The immunoglobulin heavy-chain matrix-associating regions are bound by Bright: a B cell-specific trans-activator that describes a new DNA-binding protein family. Genes Dev. 9:3067-3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Indraccolo, S., S. Minuzzo, F. Roccaforte, R. Zamarchi, W. Habeler, L. Stievano, V. Tosello, D. Klein, W. H. Gunzburg, G. Basso, L. Chieco-Bianchi, and A. Amadori. 2001. Effects of CD2 locus control region sequences on gene expression by retroviral and lentiviral vectors. Blood 98:3607-3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenuwein, T., W. C. Forrester, L. A. Fernandez-Herrero, G. Laible, M. Dull, and R. Grosschedl. 1997. Extension of chromatin accessibility by nuclear matrix attachment regions. Nature 385:269-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan, W. N. 2001. Regulation of B lymphocyte development and activation by Bruton's tyrosine kinase. Immunol. Res. 23:147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowolik, C. M., J. Hu, and J. K. Yee. 2001. Locus control region of the human CD2 gene in a lentivirus vector confers position-independent transgene expression. J. Virol. 75:4641-4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maas, A., and R. W. Hendriks. 2001. Role of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cell development. Dev. Immunol. 8:171-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.May, C., S. Rivella, J. Callegari, G. Heller, K. M. Gaensler, L. Luzzatto, and M. Sadelain. 2000. Therapeutic haemoglobin synthesis in beta-thalassaemic mice expressing lentivirus-encoded human beta-globin. Nature 406:82-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.May, C., S. Rivella, A. Chadburn, and M. Sadelain. 2002. Successful treatment of murine beta-thalassemia intermedia by transfer of the human beta-globin gene. Blood 99:1902-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyoshi, H., U. Blomer, M. Takahashi, F. H. Gage, and I. M. Verma. 1998. Development of a self-inactivating lentivirus vector. J. Virol. 72:8150-8157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naldini, L., U. Blomer, P. Gallay, D. Ory, R. Mulligan, F. H. Gage, I. M. Verma, and D. Trono. 1996. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 272:263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park, F., K. Ohashi, W. Chiu, L. Naldini, and M. A. Kay. 2000. Efficient lentiviral transduction of liver requires cell cycling in vivo. Nat. Genet. 24:49-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Queen, C., and D. Baltimore. 1983. Immunoglobulin gene transcription is activated by downstream sequence elements. Cell 33:741-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronai, D., M. Berru, and M. J. Shulman. 1999. Variegated expression of the endogenous immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene in the absence of the intronic locus control region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7031-7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webb, C. F. 2001. The transcription factor, Bright, and immunoglobulin heavy chain expression. Immunol. Res. 24:149-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zufferey, R., T. Dull, R. J. Mandel, A. Bukovsky, D. Quiroz, L. Naldini, and D. Trono. 1998. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J. Virol. 72:9873-9880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]