Abstract

Replication-competent chimeric retroviruses constructed of members of the two subfamilies of Retroviridae, orthoretroviruses and spumaretroviruses, specifically murine leukemia viruses (MuLV) bearing hybrid MuLV-foamy virus (FV) envelope (env) genes, were characterized. All viruses had the cytoplasmic tail of the MuLV transmembrane protein. In ESL-1, a truncated MuLV leader peptide (LP) was fused to the complete extracellular portion of FV Env, and ESL-2 to -4 contained the complete MuLV-LP followed by N-terminally truncated FV Env decreasing in size. ESL-1 to -4 had an extended host cell range compared to MuLV, induced a cytopathology reminiscent of FVs, and exhibited an ultrastructure that combined the features of the condensed core of MuLV with the prominent surface knobs of FVs. Replication of ESL-2 to -4 resulted in the acquisition of a stop codon at the N terminus of the chimeric Env proteins. This mutation rendered the MuLV-LP nonfunctional and indicated that the truncated FV-LP was sufficient to direct Env synthesis into the secretory pathway. Compared to the parental viruses, the chimeras replicated with only moderate cell-free titers.

Foamy viruses (FVs) are complex retroid viruses with a unique replication strategy different from that of orthoretroviruses and hepadnaviruses (18, 25). FVs, like the morphological type B and D orthoretroviruses, have their cores preformed in the cytoplasm of cells before budding at the plasma membrane (5, 13). Primate FV budding, however, takes place preferentially at intracellular membranes in addition to the plasma membrane (5, 13).

There are a number of unusual features of the prototypic FV (PFV) Env protein (15). The C terminus of the PFV transmembrane protein (TM) bears an endoplasmic reticulum retrieval signal that is responsible for the endoplasmic reticulum localization of its glycoprotein precursor gp130Env (7-9). Furthermore, PFV is unable to release particles without the coexpression of cognate Env protein (1, 2, 23). The specificity of Env incorporation into PFV cores is mediated by the leader peptide, which appears to have more unexpected features (16). The PFV LP is cleaved from the main surface (SU)-TM part of Env only very late in morphogenesis and constitutes the integral gp18 of the virion (16).

Previous studies showed that PFV Env can pseudotype murine leukemia virus (MuLV) particles in a transient cotransfection system with a MuLV vector and a Gag/Pol packaging construct (14). An enhancement of pseudotyping was achieved by replacing the cytoplasmic domain (CyD) of PFV TM with the corresponding MuLV domain (14). While removal of amino acids (aa) 2 to 25 from the PFV LP resulted in the complete loss of Env incorporation into PFV cores, pseudotyping of MuLV cores was enhanced regardless of the above-mentioned substitution of the CyD (16). These results prompted us to investigate the possibility of generating replication-competent MuLV hybrids expressing PFV Env.

Experimental design.

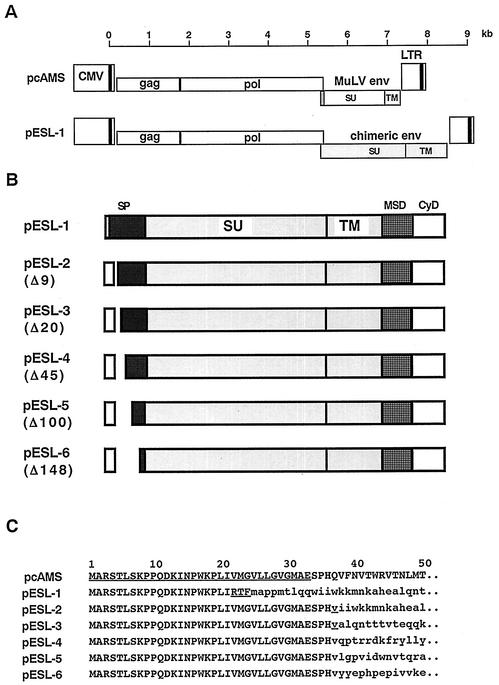

All plasmids analyzed in this study were based on the infectious MuLV molecular clone pAMS (21). To enhance the transient production of virus after transfection of 293T cells with full-length plasmids, the immediate-early gene enhancer/promoter of human cytomegalovirus was substituted for the authentic 5′ U3 region of the long terminal repeat. The resulting plasmid, pcAMS, was the backbone of the recombinant molecular clones shown in Fig. 1. pESL-1 harbors the PFV Env with inactivating mutations of the env gene-located splice sites, which are normally used by transcripts originating from the PFV internal promoter (17). In addition, in pESL-1 the CyD of the MuLV TM was inserted in place of the PFV TM CyD. Virus derived from pESL-1 contains two consecutive LP sequences at the Env N terminus. The first, a truncated LP sequence of 21 aa, was derived from MuLV to which the original start of PFV Env was fused in frame (Fig. 1). We therefore created a number of clones which harbored the complete MuLV LP of 33 aa in length plus 3 aa beyond the cleavage site followed by deletions of portions of PFV Env (28, 29). A total of 9, 20, 45, 100, and 148 aa of PFV Env were deleted from the N terminus in pESL-2, -3, -4, -5, and -6, respectively (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of wild-type MuLV and hybrid genome constructs. (A) Genetic organization of the pcAMS and pESL-1 molecular clones. (B) Details of the hybrid env genes of pESL-1 to -6. The PFV-encoded sequences are indicated as shaded boxes, and the MuLV sequences are indicated as white boxes. The identification of the PFV regions (which correspond to the LP and the membrane-spanning domain [MSD] and CyD of TM) is tentative, because the exact domain borders have not yet been determined. The CyD of the hybrid viruses was derived from MuLV, and the MSD, the extracellular domain of TM, and SU were derived from PFV. pESL-1 contains only the N-terminal 21 aa of the MuLV LP followed by the complete PFV LP. pESL-2 to -6 harbor the complete MuLV LP of 33 aa and various N-terminally deleted forms of the PFV LP. The numbers of deleted amino acids are indicated in brackets. (C) Deduced amino acid sequences of the N termini of MuLV (pcAMS) and hybrid Env proteins in single-letter code. The LP sequence of MuLV in pcAMS, the RTF motif in pESL-1 (which is derived from neither MuLV nor PFV), and the V in pESL-2 and -3, which correspond to a mutated PFV residue, are underlined. MuLV sequences are in capital letters, and PFV sequences are in lowercase letters.

Analysis of the replication competence of hybrid viruses.

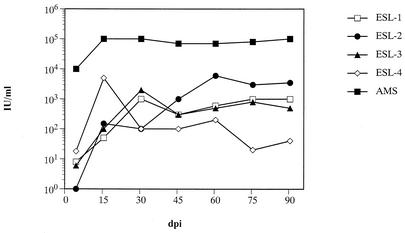

To analyze replication competence, 293T cells were transiently transfected with the molecular clones and cell-free culture supernatants were used to infect Mus dunni-LacZ cells (3). At 4 days later, virus yields in the cultures were determined by analyzing the transfer rate of the MuLV LacZ vector integrated in the M. dunni-LacZ cells on M. dunni cells by X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) staining. While after this time no infectivity was found in ESL-5- and -6-infected cells, the vector transfer of the other cultures was low but reproducibly detectable. Cell-free titers of copackaged LacZ vector were 1 to 2 IU/ml for ESL-2 and 8 to 15 IU/ml for ESL-1, -3, and -4. As shown in Fig. 2, titers increased over time and reached 1 to 2 × 103 IU/ml in ESL-1- and -3-infected cells at 30 days postinfection and 5 to 6 × 103 IU/ml in ESL-4- and -2-infected cells at 15 and 60 days postinfection, respectively. For AMS, the control virus, titers of 104 to 105 IU/ml were measured.

FIG. 2.

Development of extra-cellular viral titers in M. dunni-LacZ cells. 293T cells were transfected with the respective plasmids, and cell-free supernatant was used to infect M. dunni-lacZ cells. On the indicated day postinfection, the cell-free supernatant was analyzed for its ability to mobilize the LacZ vector integrated in the M. dunni-LacZ cells to M. dunni cells, which in turn were stained. The numbers of blue foci were estimated on the basis of the replication competence of the recombinant viruses in M. dunni-lacZ cells.

Analysis of the genetic stability of the replication-competent mutants.

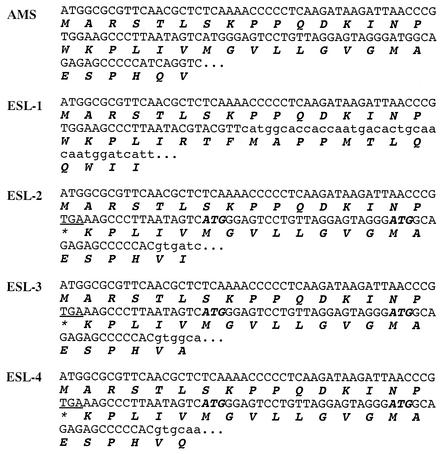

To investigate whether recombinations occurred in the replicating hybrids and to verify that the PFV env gene or its deletion mutants were still present in the recombinants, DNA from infected M. dunni-LacZ cells was analyzed by PCR and sequencing. PCR amplimers, which were generated on DNA extracted from cells on days 20 and 90 postinfection, matched perfectly to the original plasmid's fragment length (data not shown). DNA sequencing revealed the authentic sequence except for a G-to-A mutation in the third position of the 17th codon of the MuLV LP in ESL-2, -3, and -4 virus genomes (Fig. 3). This transition led to the introduction of a TGA stop codon in place of an original TGG encoding tryptophan (Fig. 3). The following two potential ATG start codons are located 6 and 14 triplets downstream (Fig. 3). No differences were found between sequences from viruses of day 20 or 90 after replication in cell culture.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the genetic stability of the replication-competent ESL-1 to -4 hybrids. DNA sequencing revealed the authentic ESL-1 sequence and a mutation of a TGG triplet in the AMS 5′ env gene to a TGA stop codon (underlined) in ESL-2 to -4. In ESL-4, the two first-interval ATG start codons are indicated in bold; MuLV sequences are in capital letters; PFV sequences are in lowercase letters.

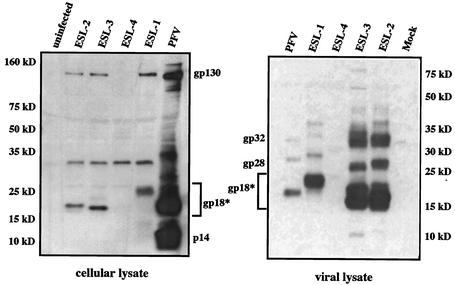

Processing and incorporation of PFV Env into hybrid viruses.

Using a PFV LP-specific rabbit antiserum (16) to analyze biochemically the expression, processing, and incorporation of PFV Env into MuLV particles, lysates from infected M. dunni-LacZ cells and from virions purified by ultracentrifugation through sucrose cushions were subjected to immunoblotting. Recent studies of PFV Env documented N-terminal cleavage with the appearance of cellular gp18 and p14 and viral gp18, gp28, and gp32 products (16). Proteins of similar sizes were present in MuLV/PFV hybrid viruses. Two bands, corresponding to the unprocessed PFV Env precursor (gp130) and the major LP cleavage product (gp18), were detected in cellular lysates from ESL-1-, ESL-2-, and ESL-3-infected cells (Fig. 4). However, p14, the unglycosylated form of gp18, was not found in these samples. Further, proteins comparable in size to those reported for the PFV particle-associated LP cleavage products (gp18, gp28, and gp32) were seen in ESL-1, -2, and -3 virion preparations (Fig. 4). As the N-terminal 21-aa fragment of MuLV Env is fused to PFV Env in ESL-1, the LP-related bands observed with this virus exhibited slower mobilities than the corresponding bands of wild-type PFV. The premature termination of the MuLV LP and consequently the truncations that occurred in the N-terminal region of LP in ESL-2 and -3, respectively, caused the LP products of these viruses to migrate slightly faster than those of ESL-1 and wild-type PFV (Fig. 4). For ESL-4, from which the first 45 aa of the PFV LP were removed, no Env precursor and LP cleavage product expression was observed in immunoblotting (Fig. 4), although virus production was detected by the vector transfer assay. Most likely, due to removal of more than 50% of the N-terminal 86-aa fragment of PFV Env (against which the antiserum was generated [16]), the viral proteins did not react with this PFV LP-specific serum.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot analysis of chimeric Env proteins with LP-specific antiserum. Lysates of virus-infected M. dunni-LacZ cells (left panel) and viral particles collected by centrifugation through sucrose cushions (right panel) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Using the ECL detection system (Amersham), after blotting the membranes were reacted with a polyclonal rabbit antiserum directed against the first 86 aa of PFV LP and developed after incubation with secondary antibody. No reactivity was found for ESL-4 virus, most likely because the deletion of 45 aa from PFV LP did not allow the reaction with the antiserum. Compared with those of the wild-type virus, the reactive proteins of the recombinants migrate slightly differently (indicated by “gp18*”). This corresponds to the introduced and acquired mutations in ESL-1 to -3. For instance, the LP in ESL-1 is of approximately 21-kDa apparent molecular mass instead of 18 kDa. Molecular mass markers and the main PFV proteins stained with this LP antiserum (21) are shown.

Host cell range and cytopathogenicity of hybrid viruses.

To determine the host cell range of the hybrid viruses, mouse NIH 3T3, bovine MDBK, hamster BHK-21, and human HT1080 and HeLa cells were inoculated with supernatants from infected M. dunni-LacZ cells and the cells were subjected to X-Gal staining to test for the transfer of the MuLV lacZ vector. Blue cells were observed in all cell lines, indicating that the hybrids were able to enter into and express genes in these cells. In contrast to results for the hybrid viruses and in accordance with the well-known entry blocking of amphotropic MuLV into these cell lines (29), no blue BHK-21 and MDBK cells were detected upon infection with parental AMS virus and X-Gal staining.

A cytopathic effect characterized by the formation of multinucleated giant cells was observed in ESL-1- to -4-infected HT1080, M. dunni, and NIH 3T3 cells (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that the hybrid viruses have a broadened host cell range compared to the parental AMS virus and induce a cytopathology similar to that of PFV (10, 13, 24).

Ultrastructure of hybrid viruses.

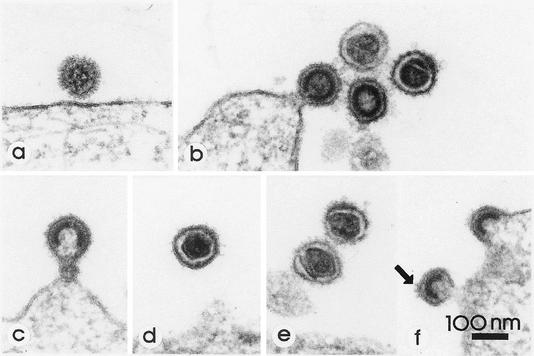

MuLV and PFV show characteristic, distinct ultrastructural morphologies (Fig. 5 a and b) (2, 4, 6). While the cores of MuLV as typical mammalian type C retroviruses are assembled concomitantly with the budding process, the cores of FVs are preassembled in the cytoplasm, i.e., they become enveloped only after cores are completely assembled (4). In contrast, a structural reorganization of orthoretroviruses takes place after release of the immature virion, which leads to maturation (6). In mature MuLV virions, a polygonal, fully condensed, and centered core often can be seen, while the cores of infectious PFV usually appear less condensed (5, 6). Another major morphological difference is the length of the SU glycoprotein structures. PFV has very prominent club-like knobs about 12 nm in length. MuLV knobs, in contrast, measure only 5 nm in length and are, therefore, barely detectable by thin-section transmission electron microscopy (4, 6). Accordingly, we expected the replication-competent hybrid viruses ESL-1 to -3 to combine the morphological features of both virus subfamilies, i.e., mammalian C-type virus cores with FV-like knobs on the envelope. As shown in Fig. 5, this is what we observed in ultrathin sections of HT1080 cells producing the wild-type and recombinant viruses. While wild-type MuLV particles are studded with barely detectable knobs (Fig. 5b), the recombinants show much longer spikes (Fig. 5c to f) which are comparable to the wild-type PFV knobs (Fig. 5a). However, differences were noted regarding the density of the hybrid spikes (compare Fig. 5a and f). This suggested that the hybrid glycoproteins are more easily shed from MuLV than are the authentic knobs from PFV.

FIG. 5.

Electron micrographs of ultrathin sections of HT1080 cells infected with parental PFV, parental MuLV, and replication-competent hybrid viruses. (a) PFV is studded with prominent knobs comparable in length to the knobs present on the hybrid viruses. Budding, immature, and mature MuLV particles are studded with tiny SU projections. (b) The core of the mature virion appears as a polygon. Compared with MuLV, both budding and mature ESL-1 (c and d), ESL-2 (e), and ESL-3 (f) hybrid viruses show distinctly longer glycoprotein knobs (arrow in panel f). The mature ESL-1 particle (d) shows a polygonal core reminiscent of the mature MuLV core. Magnification, ×120,000.

Conclusions.

The overall replication strategies, assembly pathways, and morphogenesis characteristics of spuma- and orthoretroviruses differ significantly from each other (19, 25). While PFV capsids specifically incorporate only the cognate Env protein, MuLV cores tolerate the incorporation of a wide spectrum of heterologous glycoproteins (16, 20, 23). Transient cotransfection studies of packaging and vector constructs, on the other hand, suggested that PFV Env can efficiently pseudotype MuLV cores when modified in the CyD of TM or partially deleted in the LP sequence, which has been shown to mediate the specificity of FV Env in interactions with its cognate capsid protein (14, 16). We have now extended these studies by generating MuLVs containing hybrid Env proteins. Several conclusions can be drawn from those hybrids, which were replication competent. (i) The deletion of 45 aa of the PFV LP still results in a functional Env protein that is able to pseudotype MuLV cores. (ii) The occurrence of a nonsense mutation in the env gene early during replication of ESL-2 to -4, all of which contain the complete MuLV LP sequence (11, 12, 28, 29), indicates that two consecutive LP sequences are not well tolerated by the chimeric Env proteins. (iii) Amphotropic MuLV does not readily infect hamster and bovine cell lines, while cells refractory to PFV infection are not known to date (10, 13, 15, 22, 24, 27). The extended host range of the ESL viruses provides ultimate proof for their hybrid Env nature. (iv) Cleavage and particle association of the LP has previously been shown only in the native context of FV particles (16). The incorporation of the LP into the chimeric viruses is direct evidence for the inherent property of PFV LP to be a membrane-spanning particle-associated protein. (v) MuLV and PFV are relatively unrelated but both parental viruses replicate in mice (26). The chimeric viruses characterized here are interesting tools for the investigation of the pathogenicity and immunogenicity of individual retroviral gene blocks in the living host.

Acknowledgments

We particularly thank S. Kanzler (TU Dresden) for expert technical assistance throughout the project, F. Kaulbars (Robert Koch-Institut) for her reliable work in thin section EM, and R. Riebe (Bundesforschungsanstalt für Viruserkrankungen der Tiere) for the gift of cell lines.

This work was funded by a Marie Curie Individual Fellowship from the EU (contract QLK5-CT-1999-51410) and grant support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to D.L. (Li 621/2-3) and A.R. (RE 627/6-3), the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BEO31/32/0312191), the Bayerische Forschungsstiftung (Forgen), and the Sächsisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Landwirtschaft (66-8802.3527/62 and 13-8811.61/142).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin, D. N., and M. L. Linial. 1998. The roles of Pol and Env in the assembly pathway of human foamy virus. J. Virol. 72:3658-3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer, N., M. Heinkelein, D. Lindemann, J. Enssle, C. Baum, E. Werder, H. Zentgraf, J. G. Müller, and A. Rethwilm. 1998. Foamy virus particle formation. J. Virol. 72:1610-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forestell, S. P., J. S. Dando, E. Böhnlein, and R. J. Rigg. 1996. Improved detection of replication-competent retrovirus. J. Virol. Methods 60:171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank, H. 1987. Oncovirinae: type C oncovirus, p. 273-287. In M. V. Nermut and A. C. Steven (ed.), Animal virus structure. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 5.Gelderblom, H., and H. Frank. 1987. Spumavirinae, p. 305-311. In M. V. Nermut and A. C. Steven (ed.), Animal virus structure. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 6.Gelderblom, H. R. 1991. Assembly and morphology of HIV: potential effect of structure on viral function. AIDS 5:617-638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goepfert, P. A., K. Shaw, G. Wang, A. Bansal, B. H. Edwards, and M. J. Mulligan. 1999. An endoplasmatic retrieval signal partitions human foamy virus maturation to intracytoplasmic membranes. J. Virol. 73:7210-7217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goepfert, P. A., K. L. Shaw, G. D. Ritter, Jr., and M. J. Mulligan. 1997. A sorting motif localizes the foamy virus glycoprotein to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol. 71:778-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goepfert, P. A., G. Wang, and M. J. Mulligan. 1995. Identification of an ER retrieval signal in a retroviral glycoprotein. Cell 82:1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartley, J. W., and W. P. Rowe. 1976. Naturally occurring murine leukemia viruses in wild mice: characterization of a new “amphotropic” class. J. Virol. 19:19-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson, L. E., T. D. Copeland, G. W. Smythers, H. Marquardt, and S. Oroszlan. 1978. Amino-terminal amino acid sequences and carboy-terminal analysis of Rauscher murine leukemia virus glycoproteins. Virology 85:319-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson, L. E., R. Sowder, T. D. Copeland, G. Smythers, and S. Oroszlan. 1984. Quantitative separation of murine leukemia virus proteins by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography reveals newly described gag and env cleavage products. J. Virol. 52:492-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooks, J. J., and C. J. Gibbs. 1975. The foamy viruses. Bacteriol. Rev. 39:169-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindemann, D., M. Bock, M. Schweizer, and A. Rethwilm. 1997. Efficient pseudotyping of murine leukemia virus particles with chimeric human foamy virus envelope proteins. J. Virol. 71:4815-4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindemann, D., and P. A. Goepfert. The foamy virus envelope glycoproteins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lindemann, D., T. Pietschmann, M. Picard-Maureau, A. Berg, M. Heinkelein, J. Thurow, P. Knaus, H. Zentgraf, and A. Rethwilm. 2001. Particle-associated glycoprotein signal peptide essential for virus maturation and infectivity. J. Virol. 75:5762-5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindemann, D., and A. Rethwilm. 1998. Characterization of a human foamy virus 170-kilodalton Env-Bet fusion protein generated by alternative splicing. J. Virol. 72:4088-4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linial, M. L. 1999. Foamy viruses are unconventional retroviruses. J. Virol. 73:1747-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linial, M. L., and S. W. Eastman. Particle assembly and genome packaging. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Miller, A. D. 1997. Development and applications of retroviral vectors, p. 437-473. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 21.Miller, A. D., M. F. Law, and I. M. Verma. 1985. Generation of helper-free amphotropic retroviruses that transduce a dominant-acting, methotrexate-resistant dihydrofolate reductase gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:431-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, D. G., and A. D. Miller. 1993. Inhibitors of retrovirus infection are secreted by several hamster cell lines and are also present in hamster sera. J. Virol. 67:5346-5352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietschmann, T., M. Heinkelein, M. A. Heldmann, H. Zentgraf, A. Rethwilm, and D. Lindemann. 1999. Foamy virus capsids require the cognate envelope protein for particle export. J. Virol. 73:2613-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasheed, S., M. B. Gardner, and E. Chan. 1976. Amphotropic host range of naturally occurring wild mouse leukemia viruses. J. Virol. 19:13-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rethwilm, A. 2003. Foamy virus replication strategy. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Schmidt, M., S. Niewiesk, J. Heeney, A. Aguzzi, and A. Rethwilm. 1997. Mouse model to study the replication of primate foamy viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1929-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teich, N. 1984. Taxonomy of retroviruses, p. 25-208. In R. Weiss, N. Teich, H. Varmus, and J. Coffin (ed.), RNA tumor viruses, vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbors Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Witte, O. N., A. Tsukamoto-Adey, and I. L. Weissman. 1977. Cellular maturation of oncornavirus glycoproteins: topological arrangement of precursor and product forms in cellular membranes. Virology 76:539-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witte, O. N., and D. F. Wirth. 1979. Structure of the murine leukemia virus envelope glycoprotein precursor. J. Virol. 29:735-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]