Abstract

The crystal structures of Mycobacterium smegmatis RecA (RecAMs) and its complexes with ADP, ATPγS, and dATP show that RecAMs has an expanded binding site like that in Mycobacterium tuberculosis RecA, although there are small differences between the proteins in their modes of nucleotide binding. Nucleotide binding is invariably accompanied by the movement of Gln 196, which appears to provide the trigger for transmitting the effect of nucleotide binding to the DNA-binding loops. These observations provide a framework for exploring the known properties of the RecA proteins.

Homologous genetic recombination plays an important role in the repair of DNA damage, generation of genetic diversity, maintenance of genomic integrity, and proper segregation of chromosomes. RecA protein plays a central role in all of these processes (4). The mechanistic aspects of homologous recombination promoted by the prototype Escherichia coli RecA protein (RecAEc) may arguably be the best understood, but study of its counterparts from other organisms will be essential for establishing a more general understanding.

In contrast to the much-studied RecAEc, Mycobacterium tuberculosis RecA (RecAMt) displays some unique characteristic features (13). In particular, the M. tuberculosis recA gene contains an intervening sequence in its open reading frame which subsequently undergoes protein splicing to generate the 38-kDa active form of RecA (13). Recently, our group reported the structures of RecAMt and its nucleotide complexes and compared them with the structure of RecAEc (5, 6, 19). These investigations revealed, among other aspects, subtle differences in the overall arrangement of binding site residues, which provided an explanation for the reduced levels of ATP binding and hydrolysis in RecAMt compared with those in RecAEc (6). Biochemical studies of M. tuberculosis have not only implicated the recombination machinery as being inefficient but have also revealed a high degree of illegitimate recombination. On the other hand, several independent lines of evidence suggest that the level of allele exchange in fast-growing Mycobacterium smegmatis, which is often used as a model for M. tuberculosis, is relatively high (9). Homologous recombination is also important for the generation of mutants by allele exchange, which is proposed to be useful for the development of subunit vaccines and for understanding of the molecular mechanism of pathogenesis. To gain insights into the structural basis of these differences, we analyzed the structures of M. smegmatis RecA (RecAMs), which is devoid of an intein sequence (8a), and its complexes with nucleotide cofactors.

RecAMs was purified as described elsewhere (Ganesh and Muniyappa, submitted). ADP, ATPγS, and dATP were obtained from Amersham Biosciences. Native RecAMs crystals were grown from a hanging drop of 6 mg of protein/ml in 100 mM citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 M ammonium acetate, and 6% polyethylene glycol 4000 equilibrated against 25% polyethylene glycol 4000 in the same buffer. Crystals of RecAMs-ADP, RecAMs-ATPγS, and RecAMs-dATP were grown by cocrystallization under similar conditions but in the presence of a 2 mM concentration of the appropriate nucleotide and 2 mM MgCl2. X-ray diffraction data from the native crystals and the complexes were collected at 24°C by using a MAR 300 imaging plate mounted on a Rigaku RU200 X-ray generator. In all cases, the crystal-to-plate distance was kept at 110 mm. Data were processed using the DENZO and SCALEPACK program suites (17). The data collection statistics are given in Table 1. The structure solution was achieved by molecular replacement by using AMoRe (16) with a search model constructed from RecAMt (Protein Data Bank code 1G19). All manual rebuilding was carried out using FRODO (10). Structure refinement was carried out by using CNS (2) and employing grouped B factors. Omit maps (21), along with 2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc maps, were used for building the model into the electron density.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics of RecAMs and its nucleotide complexes

| Characteristic (unit) | Native RecA | RecA-ADP | RecA-ATPγS | RecA-dATP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P61 | P61 | P61 | P61 |

| Unit cell dimension (Å) | a = b = 103.441, c = 71.765 | a = b = 103.320, c = 73.663 | a = b = 103.275, c = 73.200 | a = b = 102.960, c = 73.578 |

| Z | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Data resolution (Å) | 3.80 | 3.30 | 3.50 | 3.50 |

| Last shell (Å) | 3.94-3.80 | 3.42-3.30 | 3.62-3.50 | 3.62-3.50 |

| No. of unique reflections | 4,340 (434)a | 6,339 (649) | 5,464 (503) | 5,484 (524) |

| Completeness of data(%) | 98.5 (99.3) | 92.5 (93.8) | 95.7 (89.3) | 92.2 (94.2) |

| I/σ(I) | 4.9 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.5) | 6.7 (2.1) | 6.2 (2.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 15.2 (47.9) | 10.9 (47.0) | 10.3 (46.8) | 12.9 (44.3) |

| Resolution limit used in refinement (Å) | 15.0-3.8 | 15.0-3.3 | 15.0-3.5 | 15.0-3.5 |

| Rfactor (%) | 23.8 | 22.8 | 22.3 | 23.2 |

| Rfree (%) | 30.5 | 27.9 | 27.7 | 27.9 |

| Root mean square deviation from ideal | ||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Bond angle (°) | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Dihedral angle (°) | 23.4 | 24.3 | 24.2 | 24.6 |

| Improper angle (°) | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| No. of protein atoms | 2,222 | 2,237 | 2,265 | 2,389 |

| No. of ligand atoms | 27 | 31 | 30 | |

| No. of solvent atoms | 25 | 55 | 43 | 67 |

| Residues in Ramachandran plot (%) | ||||

| Allowed region | 96.5 | 96.5 | 93.2 | 91.1 |

| Generously allowed region | 2.7 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 7.7 |

| Disallowed region | 0.8 | 0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

Fo-Fc difference Fourier maps permitted an initial unambiguous positioning of the nucleotides in all three complexes. All structures were refined in a manner identical to that for the native RecAMs. The geometric parameters for the nucleotides were obtained from the HIC-Up database (11). A few water molecules were built into the density, where the peaks were visible at contours of at least 2.5σ in Fo-Fc and 0.8σ in 2Fo-Fc electron density maps. The stereochemical quality of all four structures was validated by using PROCHECK (14). The refinement parameters are given in Table 1. Superposition of structures was carried out using ALIGN (3).

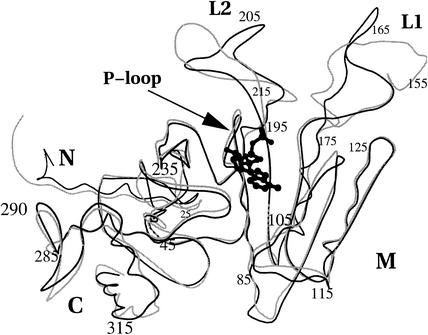

RecAMt and RecAMs have 89% sequence identity, and as expected, their structures are very similar except for the two DNA-binding loops (Fig. 1). As in RecAEc and RecAMt, the RecAMs monomer consists of a central domain (M), flanked by two smaller domains at the amino and carboxyl termini (N and C, respectively). The M domain, comprising a P loop-containing NTPase fold, hosts several functionally important regions, such as the P loop (residues 68 to 75) involved in nucleotide binding and the L1 (residues 158 to 166) and L2 (residues 196 to 211) loops involved in DNA binding.

FIG. 1.

Superposition of RecAMs (black line) and RecAMt (grey line). The N (residues 1 to 32), M (residues 33 to 270), and C (residues 271 to 330) domains are indicated. The nucleotide molecule is shown in ball-and-stick representation. The phosphate binding P loop and DNA-binding loops L1 and L2 are also indicated. All figures were prepared using MOLSCRIPT (12).

It has been well established that the formation of a nucleoprotein filament is essential for the display of all activities of RecA (7, 8). Molecules of RecAMs in the crystal structure pack around the 61 axis to form a filament, as indeed RecAEc and RecAMt do in their crystal structures. The filaments of RecA further aggregate to form bundles, as in the crystal structures of RecAEc and RecAMt. However, different views exist on the biological significance of the aggregation patterns observed in the crystal structures (1, 6, 15, 18, 20). The interactions involved in filament formation are very similar in the three structures. In contrast, there is considerable variation in the interactions responsible for bundle formation. The surface of the filament is more negatively charged in RecAMs and RecAMt than in RecAEc because of changes in sequences. There are several hydrogen bonds, including those associated with salt bridges, in RecAEc filaments. None of these hydrogen bonds exists in the RecAMs and RecAMt structures. Thus, the crystal structures indicate that bundle formation is strong in RecAEc and weak in the mycobacterial proteins. In solution studies (8a), no bundle formation could be detected in the latter.

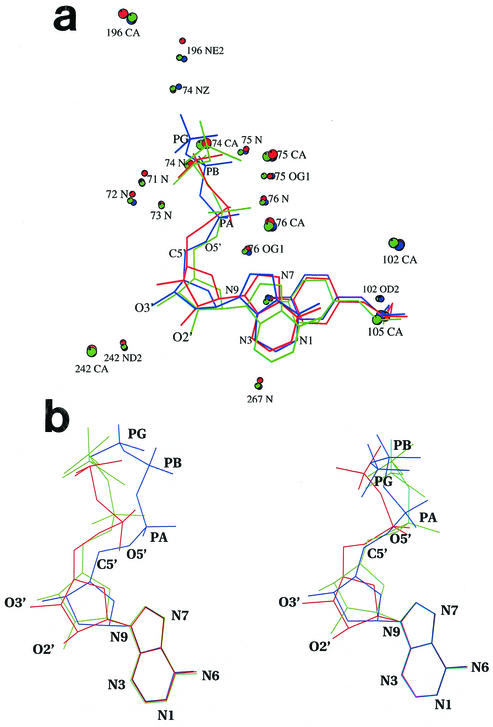

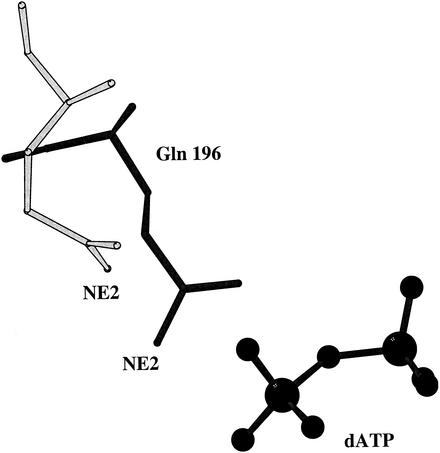

A fundamental prerequisite for the display of all activities of RecA is its binding of ATP along with magnesium. The structure of an RecAEc-ADP complex (18), determined more than a decade ago, resulted in the identification of the nucleotide binding site. However, only the α-carbon positions in the complex are available. The first detailed discussion of RecA-nucleotide interactions resulted from the analyses of the complexes of the M. tuberculosis protein with different nucleotides (5, 6). The nucleotide binding region of RecAMt is characterized by its expansion compared with that in RecAEc, despite substantial sequence identity in the concerned regions, thus accounting for the reduced nucleotide binding affinity of RecAMt (5, 6). The same expansion in relation to RecAEc also occurs in RecAMs. In both cases, this expansion occurs in the native structure itself and is not dependent on nucleotide binding. The residues with oxygen or nitrogen atoms within 4 Å of phosphate oxygens in any one of the seven RecAMt and RecAMs complexes are residues 69 to 76 (the P loop) and 196. These residues constitute the phosphate binding region. Likewise, residues 105 and 242 can interact with sugar oxygens. The residues which interact with the base are 102, 105, and 267. The polar protein atoms which are within 4 Å of the polar atoms in the nucleotide in most or all of these seven complexes are Ser 71 N, Ser 72 N, Gly 73 N, Lys 74 N, Thr 75 N, Thr 75 OG1, Thr 76 N, Thr 76 OG1, Asp 102 OD2, Tyr 105 OH, Gln 196 NE2, Asn 242 ND2, and Gly 267 N (Fig. 2a). Tyr 105, in addition to interacting with O4′ through its hydroxyl group, stacks against the base. The α-carbons of the 11 residues involved in nucleotide binding in the two native structures superpose with a maximum deviation of 0.5 Å, indicating that the geometries of the binding sites in RecAMs and RecAMt are essentially the same. When the corresponding atoms in the complexes are superposed on those in the native structure, the α-carbon of Gln 196 deviates by 1 Å or more. Many side chain atoms of this residue deviate by more than 2 Å (Fig. 3). This indicates substantial movement of Gln 196 with respect to the other binding site residues. Thus, the position of 196 appears to be highly sensitive to nucleotide binding.

FIG. 2.

(a) Superposition of the nucleotides and their surroundings in the complexes with ADP (red), ATPγS (green), and dATP (blue). The protein atoms that interact with the nucleotide in all or most structures of RecAMs and RecAMt are shown. Where this atom belongs to the side chain, the α-carbon position is also indicated. The tyrosyl side chain, which stacks against the base in addition to interacting with the sugar, is shown in full. (b) Comparable views, based on superposition of bases, of nucleotides in RecAMs (left) and RecAMt (right). ADP, ATPγS, and dATP are shown in red, green, and blue, respectively.

FIG. 3.

The position of Gln 196 with respect to the two terminal phosphates of dATP in the RecAMs-dATP complex (black). The position of this residue in the native structure, obtained by the superposition of all α-carbon atoms in the two structures, is also indicated (grey) for comparison.

Although the geometries of the binding sites themselves are nearly the same in all of the complexes, there is considerable variation in the positions of the nucleotides, as can be seen in Fig. 2a. The same is true in the RecAMt complexes as well. These variations arise partly because of the conformational variations in the nucleotides themselves, as can be seen in Fig. 2b, where the nucleotides are compared by superposing their bases. The planar bases superpose very well in RecAMs and RecAMt complexes, with almost all atomic deviations being less than 0.1 Å. Among the sugar atoms, O5′, involved in the linkage to a phosphate group, and the attached C5′ exhibit the maximum deviations. In the absence of O2′, O3′ in dATP tends to move towards the position of O2′ in the complexes involving ADP and ATPγS. The largest deviations are exhibited by the phosphate groups. The deviations in the first, second, and terminal phosphorus atoms between the RecAMt complexes with ATPγS and dATP are 1.9, 1.4, and 1.4 Å, respectively. The corresponding deviations in the RecAMs complexes are 2.1, 3.1, and 2.5 Å, respectively. The nucleotides as a whole move in the crystal structures such that deviations in atomic positions in them between the RecAMs and RecAMt complexes are reduced from what they are with respect to an internal coordinate system. In any case, the atomic deviations between ATPγS and dATP are larger in the RecAMs complexes than in the RecAMt complexes. The differences outlined above provide a framework for examining the biochemical differences in nucleotide binding by RecAMs and RecAMt (8a).

DNA-binding loops L1 and L2 are undefined in the RecAEc structure. In the RecAMt structures, L1 is defined in one complex and L2 is defined in another (5). There is reasonable evidence for the loops in the RecAMs-dATP complex. Their conformation and orientation appear to be different from those observed in the two RecAMt complexes. However, it is too early to draw firm conclusions on the basis of these differences, especially as the loops are disordered in most of the relevant crystal structures.

Analyses of the mycobacterial RecA crystal structures presented here support the earlier suggestion (5) of a plausible structural basis for the relation between nucleotide binding and DNA binding. As discussed above, nucleotide binding is invariably accompanied by the movement of Gln 196. Indeed, the most conspicuous effect of nucleotide binding appears to be the movement of this residue. Gln 196 is the first residue in the L2 loop, and it could presumably function as the link for propagation of the effects of nucleotide binding to L2. However, the route for this propagation of the effect to L1 is less obvious. In this regard, the previous suggestion (5) of the involvement of a connector segment between L1 and L2 deserves further exploration.

Acknowledgments

The diffraction data were collected on an imaging plate detector at the X-ray Facility for Structural Biology, which is supported by the Department of Science and Technology and the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India. The use of facilities at the Supercomputer Education and Research Centre and the Interactive Graphics Based Molecular Modelling Facility and the Bioinformatics Centre (both supported by DBT) is acknowledged. The work forms part of a DBT-sponsored genomics program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brenner, S. L., A. Zlotnick, and J. D. Griffith. 1988. RecA protein self-assembly. Multiple discrete aggregation states. J. Mol. Biol. 204:959-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brünger, A. T., P. D. Adams, G. M. Clore, W. L. Delano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J. S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system (CNS): a new software system for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D54:905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen, G. E. 1997. ALIGN: a program to superimpose protein coordinates, accounting for insertions and deletions. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30:1160-1161. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox, M. M. 2000. Recombinational DNA repair in bacteria and the RecA protein. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 63:311-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datta, S., N. Ganesh, Nagasuma R. Chandra, K. Muniyappa, and M. Vijayan. 2003. Structural studies on MtRecA-nucleotide complexes: insights into DNA and nucleotide binding and the structural signature of NTP recognition. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 50:474-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datta, S., M. M. Prabu, M. B. Vaze, N. Ganesh, N. R. Chandra, K. Muniyappa, and M. Vijayan. 2000. Crystal structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RecA and its complex with ADP-AlF4: implications for decreased ATPase activity and molecular aggregation. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4964-4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egelman, E. H. 1993. What do X-ray crystallographic and electron microscopic structural studies of the RecA protein tell us about recombination? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 3:189-197. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flory, J., S. S. Tsang, and K. Muniyappa. 1994. Isolation and visualization of active presynaptic filaments of RecA protein and single stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7026-7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Ganesh, N., and K. Muniyappa. The Mycobacterium smegmatis RecA protein is structurally similar but functionally distinct from Mycobacterium tuberculosis RecA. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Husson, R. N., B. E. James, and R. A. Young. 1990. Gene replacement and expression of foreign DNA in mycobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:519-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones, T. A. 1978. A graphics model building and refinement system for macromolecules. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 11:268-272. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleywegt, G. J., and T. A. Jones. 1998. Databases in protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D54:1119-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar, R. A., M. B. Vaze, N. R. Chandra, M. Vijayan, and K. Muniyappa. 1996. Functional characterization of the precursor and spliced forms of RecA protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry 35:1793-1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereo chemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morimatsu, K., M. Takahashi, and B. Norden. 2002. Arrangement of RecA protein in its active filament determined by polarized-light spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11688-11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navaza, J. 1994. AMoRe—an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. A50:157-163. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otwinowski, Z., and W. Minor. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Story, R. M., and T. A. Steitz. 1992. Structure of the RecA protein-ADP complex. Nature 355:374-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Story, R. M., I. T. Weber, and T. A. Steitz. 1992. The structure of the E. coli RecA protein monomer and polymer. Nature 355:318-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VanLook, M. S., X. Yu, S. Yang, A. L. Lai, C. Low, M. J. Campbell, and E. H. Egelman. 2003. ATP-mediated conformational changes in the RecA filament. Structure 11:187-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijayan, M. 1980. Phase evaluation and some aspects of the Fourier refinement of macromolecules, p. 19.01-19.26. In R. Diamond, S. Ramaseshan, and K. Venkateshan (ed.), Computing in crystallography. Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore, India.