Abstract

The β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases are members of the thiolase superfamily and are key regulators of bacterial fatty acid synthesis. As essential components of the bacterial lipid metabolic pathway, they are an attractive target for antibacterial drug discovery. We have determined the 1.3 Å resolution crystal structure of the β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II (FabF) from the pathogenic organism Streptococcus pneumoniae. The protein adopts a duplicated βαβαβαββ fold, which is characteristic of the thiolase superfamily. The two-fold pseudosymmetry is broken by the presence of distinct insertions in the two halves of the protein. These insertions have evolved to bind the specific substrates of this particular member of the thiolase superfamily. Docking of the pantetheine moiety of the substrate identifies the loop regions involved in substrate binding and indicates roles for specific, conserved residues in the substrate binding tunnel. The active site triad of this superfamily is present in spFabF as His 303, His 337, and Cys 164. Near the active site is an ion pair, Glu 346 and Lys 332, that is conserved in the condensing enzymes but is unusual in our structure in being stabilized by an Mg2+ ion which interacts with Glu 346. The active site histidines interact asymmetrically with Lys 332, whose positive charge is closer to His 303, and we propose a specific role for the lysine in polarizing the imidazole ring of this histidine. This asymmetry suggests that the two histidines have unequal roles in catalysis and provides new insights into the catalytic mechanisms of these enzymes.

The β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases catalyze the addition of two-carbon units onto the growing acyl chain during the elongation phase of fatty acid synthesis. This enzymatic activity involves what is an irreversible chemical event in biosynthetic pathways, the formation of a carbon-carbon bond via a Claisen-like condensation reaction (15). These condensing enzymes are members of a superfamily of enzymes whose members all catalyze essentially the same reaction. Included in the superfamily are the thiolases involved in fatty acid degradation (β-oxidation) (46), or sterol biosynthesis (25), and the related enzymes that synthesize polyketides in plants and bacteria (18). Structural studies on this superfamily of enzymes have revealed that they share a common βαβαβαββ topology which is duplicated by an internal pseudodyad that may have arisen by gene duplication (26). Members of the superfamily that have been structurally characterized include the peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-coenzyme A (3-ketoacyl-CoA) thiolases from a variety of organisms (26), an array of bacterial fatty acid-condensing enzymes (8, 19, 31, 36, 38, 40, 41, 45), and the polyketide chalcone synthase (13). Based on the structural and functional differences between the enzymes, the superfamily is subdivided into three classes (31). The thiolases form one group, the fatty acid elongation-condensing enzymes form a second group, and those involved in polyketide synthesis and in the initial fatty acid condensation reaction constitute a third group.

Structural studies on the binding of substrates and inhibitors, as well as mutagenesis studies, have provided insights into the mechanisms by which the condensing enzymes of fatty acid synthesis recognize and bind substrates and catalyze the condensation reaction (15). The elongating substrate is attached as a thioester to the terminal sulfur atom of the pantetheine moiety of acyl carrier protein (ACP). The elongation reaction catalyzed by the condensing enzymes comprises two steps. In the first step, the transacylation reaction, ACP deposits the substrate on the active site cysteine of the condensing enzyme. During the second step, the decarboxylation reaction, the condensing enzyme catalyzes the transfer of the substrate to a malonyl moiety, also attached to ACP, which releases its terminal carboxyl group as CO2 in the process. The result is an addition of two carbons to the growing lipid attached to ACP. The subsequent three reactions of fatty acid synthesis—reduction, dehydration, and second reduction—are needed to convert the keto group into a methylene group before the cycle can restart. In bacteria and plants, the catalytic components and the ACP are discrete and independent enzymes, and this arrangement is referred to as the type II or dissociated fatty acid synthase (FAS) (21). In mammals and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), the components are fused into a multidomain complex referred to as the type I or associated FAS system (47). Although the sequence similarity is marginal, it is clear from conserved active site residues that the condensing enzymes within both types of FAS architecture are related and have similar catalytic mechanisms. This is supported by the finding that cerulenin is an irreversible inhibitor of both type I and type II condensing enzymes (6, 50) and mimics the transition state of the catalytic reaction when buried at the active site (32, 39).

The best-characterized type II system is that from Escherichia coli (21, 42). This organism has three condensing enzymes. Synthase I, or FabB, is required for a critical step in the elongation of unsaturated fatty acids, and mutants (fabB) lacking synthase I activity require supplementation with exogenous unsaturated fatty acids to support growth (7, 43). Synthase II, or FabF, controls the temperature-dependent regulation of fatty acid composition, and mutants lacking synthase II activity (fabF) are deficient in the elongation of palmitoleate to cis-vaccenate but grow normally under standard culture conditions (10, 14). Synthase III, or FabH, is a specialized initiating condensing enzyme that the type II system requires to generate the first four-carbon unit from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP (20). The crystal structures of all three enzymes from E. coli have been determined (8, 19, 36).

Fatty acid synthesis is recognized as a promising target for the development of new antibacterial agents (16). Although lipid synthesis is essential for cell viability in all organisms, the differing architectures of the type I and II systems together with their evolutionary separation suggests that agents can be identified that will specifically target the bacterial system. Indeed, triclosan (17, 28) and isoniazid (2) are two commonly used antibacterial agents that are known to target fatty acid synthesis. The fungal antibiotic thiolactomycin (TLM) specifically targets bacterial condensing enzymes (49), and the search is intensifying for TLM derivatives that specifically target these enzymes from major pathogens (11, 44). To complement these efforts, we have completed the structure of FabF from Streptococcus pneumoniae (spFabF) at 1.3-Å resolution, the highest resolution for any member of the superfamily. The structure is refined to very high accuracy and reveals the geometry of the active site in exquisite detail. Our high-resolution data provide new insights into the mechanism of the condensing enzymes as well as its evolutionary history.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification.

The spFabF gene was amplified from S. pneumoniae strain RN4220, cloned into pET15b, and expressed and purified to homogeneity by using previously described techniques (39). Purified enzymes were then dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM dithiothreitol; concentrated with an Amicon stirred cell; and stored in 50% glycerol at −20°C.

Crystallization and data collection.

Crystals of spFabF protein were grown by using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. The protein was dialyzed into 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol and concentrated to 20 mg/ml, as measured by the Bradford assay (3). Crystallization experiments were set up with equal volumes (2 μl) of protein and a well solution of 0.25 M magnesium acetate, Tris-HCl (pH 7.75), and 15% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 3350. Two distinct crystal forms grew in 1 week at 18°C. Crystals of both forms were frozen in a mixture of equal parts paratone-N and mineral oil. Using the rotation method and an oscillation angle of 1°, complete datasets were collected on both crystals at the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) beamline at the Advanced Photon Source. The triclinic form diffracted to 2.1 Å, and the orthorhombic form diffracted to 1.3 Å. All data were processed by using HKL2000 (37), and the relevant statistics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data reduction statistics

| Parameter (unit) | Resulta for form:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | Orthorhombic | |

| Spacegroup | P1 | P21212 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 61.5, 71.6, 96.1 | 63.7, 90.0, 62.2 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 89.9, 83.1, 69.1 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0-2.1 (2.18-2.1) | 15.0-1.3 (1.32-1.30) |

| Multiplicity | 2.1 (1.8) | 8.5 (7.1) |

| Rsymb | 0.038 (0.254) | 0.080 (0.351) |

| I/Σ | 18.7 (1.7) | 30.7 (3.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 92.6 (58.6) | 99.8 (99.8) |

| No. of reflections | 937,038 | 1,002,530 |

| No. of unique reflections | 90,012 | 88,233 |

Values in parentheses refer to the highest-resolution shell.

Rsym = ΣΣ|Ii − Im|/ΣΣIi, where Ii is the intensity of the measured reflection and Im is the mean intensity of all symmetry-related reflections.

Solution of the triclinic crystal form.

The structure of the triclinic form was determined by using the molecular replacement (MR) method. A BLAST (1) search of the Protein Data Bank returned the β-ketoacyl synthase II (FabF) from Synechocystis sp. as having the highest sequence identity (23.5%), and the structure of this enzyme (Protein Data Bank code 1E5M) was used to create a search model for the MR procedure. Consideration of the Matthew's coefficient of the triclinic form suggested that the crystallographic asymmetric unit (ASU) contained two dimers, and a dimer was therefore constructed and used as the search model. The program AMoRe (34) was used to determine the MR solution. Rigid body refinement of the MR solution and calculation of the initial 2Fo-Fc, and Fo-Fc maps were performed by using the Crystallography and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance System (CNS) (4). The map and MR solution were displayed by using the program O (22), and the S. pneumoniae FabF sequence (GenBank accession no. AAF98276) was built into the density. Five cycles of refinement were performed. Each cycle consisted of simulated annealing in CNS with fourfold noncrystallographic symmetry restraints followed by manual rebuilding in O. Waters were then picked by using CNS. Four large peaks in the density (one per monomer in the ASU) were interpreted as Mg2+ ions, since these were present in the crystallization buffer. All waters were visually inspected, and suspect waters due to poor density or nonideal hydrogen-bonding geometry were rejected. A final round of energy minimization with REFMAC (33) completed the refinement. The statistics of the final refined model are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Refinement statistics

| Parameter (unit) | Result for form:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | Orthorhombic | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30.0-2.1 | 15.0-1.3 |

| No. of reflections in working set | 67,647 | 83,903 |

| No. of reflections in test set | 2,083 | 2,038 |

| No. of protein atoms in ASU | 12,264 | 3,112 |

| No. of Mg2+ ions in ASU | 4 | 2 |

| No. of water molecules in ASU | 216 | 325 |

| Rwork | 0.208 | 0.139 |

| Rtest | 0.235 | 0.160 |

| RMS deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.62 | 1.81 |

| Mean B, main chain (Å2) | 41.92 | 11.58 |

| Mean B, side chains and water molecules (Å2) | 44.30 | 15.91 |

| Ramachandran plot (percent of amino acids in region) | ||

| Most favored | 89.1 | 90.3 |

| Additionally allowed | 9.9 | 8.8 |

| Generously allowed | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Disallowed | 0.3 | 0.0 |

Solution of the orthorhombic crystal form.

The structure of the orthorhombic form was determined by MR by using the structure of the triclinic form to construct the search model. The Matthew's coefficient of the orthorhombic crystal form indicated that the ASU most likely contained a single monomer of SpFabF, and a single monomer from the triclinic ASU was chosen to serve as the search model. The program AMoRe was used to solve the MR problem. An initial rigid body refinement (CNS) was followed by two cycles of simulated annealing (CNS) and manual rebuilding (O). Waters were picked (CNS) and followed with a round of energy minimization (CNS). Two large peaks in the density were again interpreted as Mg2+ ions. At this point, the Rwork was 0.195 and the Rfree was 0.203. REFMAC was then employed to refine the structure by using energy minimization, allowing full anisotropic refinement of B factors. The statistics of the final, refined model are shown in Table 2.

Protein Data Bank accession numbers. The refined coordinates of both the orthorhombic form (accession code 1OX0) and the triclinic form (accession code 1OXH) of spFabF have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank.

RESULTS

Description of the crystal structures.

Analysis of the final, refined structure of the triclinic crystal form showed that the model had good stereochemistry (Table 2). A Ramachandran analysis performed with PROCHECK (24) showed only four residues (Leu 339 in each of the four monomers) in the disallowed region. These residues have well-defined densities and are close to the boundary between disallowed and generously allowed regions. The final R factors (Rwork = 0.208; Rfree = 0.235) indicate good agreement of the model with the experimental data. All monomers in the ASU are equally complete. Only the N-terminal methionines and the final two C-terminal amino acids (Asn 412 and Arg 413) were not visible in the electron density. These residues are presumably disordered in this crystal form. The triclinic crystal form contains four monomers per ASU. Each monomer contains 408 amino acids. These four monomers are arranged in two dimers, which is consistent with the fact that its homologs are dimers both in solution and in their crystal structures (19, 31, 36) and pack with a Matthew's coefficent of 2.21 Å3/Da. The conformations of the four monomers present in the ASU are almost identical, except for variations in the conformations of the side chains at crystal contacts which differ between the four monomers. In addition, one Mg2+ ion per monomer is bound near each active site, as described below.

The structural analysis of the final, refined structure of the orthorhombic crystal form showed excellent stereochemistry, which is to be expected from a structure refined to such high resolution (Table 2). The final R factors (Rwork = 0.139 and Rfree = 0.160) show excellent agreement between the model and the experimental data. Only the final two C-terminal residues are not visible in the structure, and these are presumably disordered. Five residues in the proximal region of the His tag before it attaches to the N-terminal methionine were also visible in the electron density. A portion of the final 2Fo-Fc electron density map in the active site region is shown in Fig. 1. The structure of the orthorhombic crystal form contains one monomer per ASU and contains 414 amino acids. The crystal packing is compact (Matthew's coefficient = 1.95 Å3/Da), and the biological dimer is created by the crystallographic two-fold axis parallel to the c axis of the crystal. The crystal structure showed two Mg2+ bound per monomer. One is located near the active site, approximately 9 Å from the active site Cys 164 (see Fig. 6A), and the other is involved in a crystal contact between dimers.

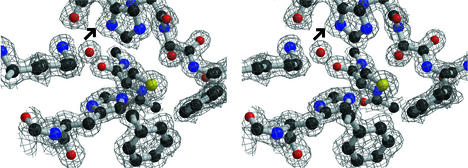

FIG. 1.

The electron density in the active site, contoured at the 1-σ level. The distortion of the electron density at the ND nitrogen in His 303 is indicated by the arrow. This figure was made with BOBSCRIPT (12) and rendered with Raster3D (29).

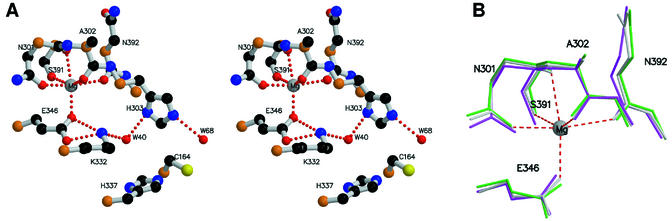

FIG. 6.

(A) A stereo view of the magnesium cation binding site in FabF from S. pneumoniae and its relation to the active site. Water molecules are labeled W40 and W68. Coordinate bonds to the Mg2+ and hydrogen bonds are indicated with dotted red lines. The α carbons are colored orange. (B) A superposition of the cation binding site of S. pneumoniae FabF (gray) with the conserved features of E. coli FabF (magenta) and Synechocystis sp. FabF (green). Residues from S. pneumoniae are labeled. All figures were made by using MOLSCRIPT (23) and rendered with Raster3D (29).

A comparison of the structures of the triclinic and orthorhombic crystal forms shows only minor differences in the conformations of the side chains that mediate the different intermolecular contacts in the two crystal lattices. There is significantly less disorder in the orthorhombic crystal form, as is demonstrated by a comparison of mean B factors (Table 2). Both main and side chain B factors for the orthorhombic form (〈BMC〉 = 11.6 Å2; 〈BSC〉 = 15.9 Å2) are significantly less than the corresponding values calculated for the triclinic form (〈BMC〉 = 41.9 Å2; 〈BSC〉 = 44.3 Å2) calculated with CCP4 (5). Since the orthorhombic crystal form is refined to a much higher resolution, the descriptions and associated figures of the molecule refer to this structure.

Description of the structure of spFabF.

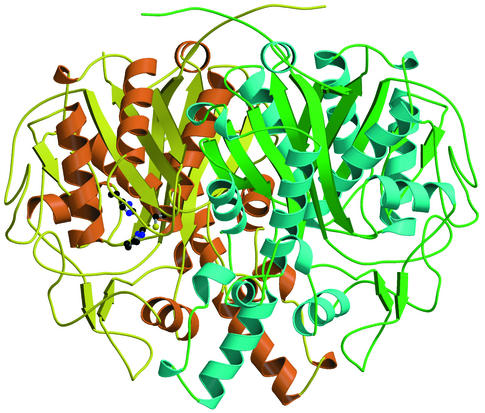

Structurally, the spFabF protein is similar to its homologs, and its structure is shown in Fig. 2. Since the overall fold is described in detail elsewhere (Synechocystis sp. FabF [31], E. coli FabF [19], and E. coli FabB [36]), our discussion is brief. The spFabF protein forms an α/β structure that can be divided into two halves, an N-terminal region comprising residues 1 to 250 and a C-terminal region comprising residues 251 to 409. The basic fold of the superfamily was first described for a yeast thiolase (26), and the two halves have identical core structures comprising a five-stranded mixed β-sheet that is flanked on one side by two α-helices and on the other by a single α-helix. A single copy of this duplicated topology was identified in the first domain of phosphoglucomutase (26). The basic topology of this duplicated motif, βαβαβαββ, is modified differently in the two halves of the monomer by distinct insertions. In the N-terminal half there are three insertions, and the secondary structure can be written as β I1 α β I2 α β α β I3 β, where the letter I indicates the location of an insert, and the inserts are numbered one through three. The C-terminal region contains a single insert, insert number four, and this half of the monomer is described as β α β α β α I4 β β. To reflect this topological identity, we have named the core secondary structural elements Nβ1 to Nβ5 and Nα1 to Nα3 in the N-terminal region and Cβ1 to Cβ5 and Cα1 to Cα3 in the C-terminal region (48). An axis of pseudosymmetry runs between the β-sheets and passes through the point near where the N termini of helices Nα3 and Cα3 meet in the structure. The close structural superposition of the two pseudosymmetrical halves is shown in Fig. 3.

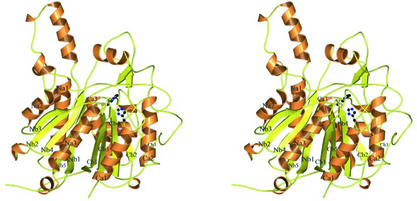

FIG. 2.

A stereo view of the FabF monomer from S. pneumoniae. All α-helices are orange and labeled a1 through a3, and all β-strands are yellow and labeled b1 through b5. Secondary structural elements in the N-terminal half are labeled with an N and those in the C-terminal half are labeled with a C. The active site residues, Cys 164, His 303, and His 336, are represented as ball-and-stick figures. This figure was made by using MOLSCRIPT (23) and rendered with Raster3D (29).

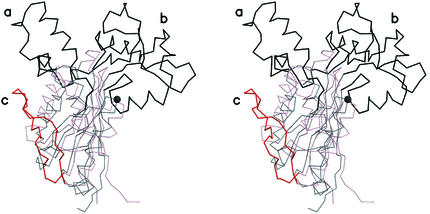

FIG. 3.

The superposition of the N- and C-terminal halves of FabF from S. pneumoniae, showing the location of the major insertions in the sequence. The N-terminal domain is black, and the C-terminal domain is red. Insertions are indicated with darker colors. The insertion creating the acyl-chain-binding pocket is I2 and is labeled a. The insertions creating the pantetheine binding site are I1 and I3 and are labeled b. The single insertion in the C-terminal domain formed by I4 is labeled c. The location of the active site cysteine (Cys 164) is marked with a black sphere. This figure was made by using MOLSCRIPT (23) and rendered with Raster3D (29).

The structure of the spFabF dimer is shown in Fig. 4. The dimerization interface is large and complex, taking advantage of both hydrophobic packing, salt bridges, and numerous hydrogen-bonding interactions. The buried surface area measures 3,344 Å2. Notable regions within the interface include a cluster of methionines comprising residues 133, 142, 149, and 269′ (the prime indicates an amino acid from the opposite monomer) and an anti-parallel-β-sheet interaction between Nβ3 and Nβ3′. This latter contact is at the center of the interface and results in the extension of the 5-stranded β-sheet at the core of the N-terminal region to a 10-stranded β-sheet which spans both monomers in the dimer.

FIG. 4.

The FabF dimer from S. pneumoniae. In monomer one, all α-helices are orange and all β-strands and coil regions are yellow. In monomer two, all α-helices are blue and all β-strands and coil regions are green. The active site triad (Cys 164, His 303, and His 337) is represented with ball-and-stick figures in monomer one. This figure was made by using MOLSCRIPT (23) and rendered with Raster3D (29).

DISCUSSION

The active site and catalytic mechanism.

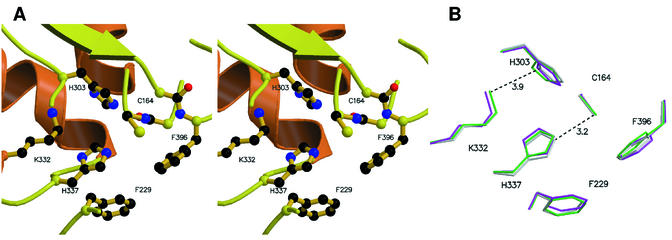

The active site of the condensing enzyme superfamily is a catalytic triad composed of a central cysteine residue, and either two histidines (as in FabF and FabB) or a histidine and an asparagine (as in FabH and the thiolases). This active site triad is located at the convergence of the N termini of the two helices, Nα3 and Cα3, that are related by the axis of pseudosymmetry of the monomer. The cysteine is located at the N terminus of helix Nα3. Other important groups within the active site include a conserved phenylalanine and two main-chain amides that constitute an oxyanion hole adjacent to the cysteine. The active site is located at the base of a tunnel which accommodates the pantetheine moiety of holo-ACP, to which the substrate is attached. The structure of the spFabF active site is shown in Fig. 5A. In spFabF, the active site residues are Cys 164, His 303, and His 337, the conserved phenylalanine is Phe 229, and the two important main-chain amides belong to Cys 164 and Phe 396. Cys 164 and His 337 are related by the pseudosymmetry, i.e., they are in approximately corresponding positions in the structures of the N-terminal and C-terminal halves, and the third residue (His 303) lies at the C-terminal end of strand Cβ2. The active site tunnel is approximately 15 Å deep and 10 Å wide, and the interior surface of this tunnel is populated by several highly conserved residues whose possible role in binding the pantetheine moiety of holo-ACP is discussed below.

FIG. 5.

(A) A stereo view of the active site of FabF from S. pneumoniae showing the major conserved residues and the oxyanion hole. The oxyanion hole is created by the amide nitrogens of Cys 164 and Phe 396. Secondary structural elements are colored as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (B) A superposition of the active sites of S. pneumoniae FabF (gray) with E. coli FabF (magenta) and Synechocystis sp. FabF (green). For SpFabF, distances between Lys 332 NZ and His 303 ND and between Cys 164 SG and His 337 NE are indicated in angstroms. All figures were made by using MOLSCRIPT (23) and rendered with Raster3D (29).

A critical step in the transacylation reaction is the initial nucleophilic activation of the active site cysteine. One proposal is that one or both of the histidines play a role in abstracting the proton from the cysteine thiol (19, 31). However, mutagenesis of the histidines to alanine does not eliminate transacylation to the active site cysteine of FabB (27), and in the case of FabH, it actually augments the nucleophilicity of the cysteine as reflected in the increased rate of the transacylation half-reaction (8). We proposed that activation of the cysteine is effected through the electric dipole moment of helix Nα3, which is directed towards the sulfur atom, and enhances the nucleophilicity of the cysteine sulfur by lowering its pKa. The orientation of this dipole towards the active site of this superfamily was noted in the first thiolase structure (26), and there is no question that it has a profound effect on the electrostatic environment of the condensation enzyme active site. The magnitude of the helix dipole effect is sensitive to the direction of the α-helix axis, and in the spFabF structure, the orientation of helix Nα3 is rigidly held in place by specific contacts, both hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding. The C-terminal end of the helix is immobilized by a cluster of aromatic side chains that interacts with a partner cluster across the dimer interface (Phe 175, Phe 180, and Phe 182). At the N-terminal end, immediately C-terminal to the active site cysteine, the five polar residues, Ser 165, Ser 166, Ser167, Asn 168, and Asp 169, form specific hydrogen-bonding interactions with surrounding groups despite being located within the hydrophobic core of the molecule. Furthermore, the importance of positioning Cys 164 in line with the dipole is highlighted by the unusual backbone conformation of Ala 163 (ϕ = 51° and ψ = −123°). This strained conformation of Ala 163 is required in order to maintain the special position of Cys 164 in line with the helix.

Another important issue is the role of the histidines in the active site. The hypothesis that the role of the histidines is to hydrogen bond with the thioester carbonyl oxygen of the malonyl-ACP substrate, to stabilize the negative charge on this oxygen in the decarboxylation transition state, is largely based on the structures of the E. coli FabB enzyme in complex with the inhibitors TLM (39) and cerulenin (32, 39). Indeed, mutagenesis of either histidine in FabB results in the loss of malonyl-ACP decarboxylation to acetyl-ACP activity (27). This role requires that both histidines are oriented with their NE atoms pointed towards the active site cysteine and that both NE atoms are protonated. The rotamer of His 303 is revealed in our structure by the fact that its ring nitrogens are clearly hydrogen bonded to water molecules in such a way as to direct the NE nitrogen toward the active site cysteine (Fig. 6A). The rotamer of His 337 is indicated by hydrogen bonds with the backbone amide nitrogen of residue 336 and the active site cysteine sulfur, which places its NE nitrogen toward the active site also. As for the protonation states of these nitrogens, even with a 1.3-Å resolution structure, one cannot unequivocally determine this directly from the electron density. Interestingly, there is a significant bulge (3.5 σ in the Fo-Fc map) in the electron density of the ND nitrogen of His 303 (Fig. 1). This feature does not exist on any of the other histidines within the structure refined to high accuracy by using anisotropic temperature factors. A similar feature exists in the crystal structure of complexes of E. coli FabB with fatty acids (35). In that structure, a hydroxide ion was modeled into the density (1.9-Å data), and it was argued that the negative charge on the hydroxide would influence the ND of His 303, causing it to be protonated. This implies that the NE nitrogen, which points toward the active site, would be unprotonated. We attempted to model this hydroxide ion into our higher resolution data, but we failed. The final, refined hydroxide position was 1.2 Å from the ND nitrogen (much too close for a nitrogen-hydroxide H bond) and generated a large, negative peak in an Fo-Fc map (absolute peak height > 4.5 σ). Thus, the presence of a hydroxide ion, and any mechanism which invokes a role for such an ion, is ruled out by our higher resolution data.

Our structural results indicate a crucial role for the conserved Lys 332 in determining the protonation state of His 303 ND. This lysine, together with Glu 346, forms a conserved buried ion pair adjacent to the active site that has been previously noted in these enzymes. This has led one group to suggest that the role for this lysine is solely structural (19). However, mutagenesis of this residue results in an enzyme that lacks malonyl-ACP decarboxylation activity (27), suggesting that it also plays a more active role in catalysis. We suggest that the positive charge of the ɛ-amino group polarizes His 303 such that the NE atom on the opposite side of the ring is protonated and in a position to hydrogen bond to the carbonyl group of the substrate. The positive charge on Lys 332 is 3.9 Å from His 303 ND, as opposed to 4.6 Å from His 337 ND. Similar arrangements are also observed in the structures of related condensing enzymes (19, 30, 31) (Fig. 5B), and this suggests distinct roles for the two histidines in catalysis. For example, His 303 may have the greater role in stabilizing the charge buildup in the decarboxylation transition state. The use of charged or polar groups to modulate the charge distribution on the imidazole ring of histidine is common within enzyme active sites. A recent example that demonstrates the use of a negative charge, i.e., opposite to that which we propose for the condensation enzymes, is within the active site of tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (9). In this case, two histidines perform two sequential nucleophilic attacks to cleave a tyrosine-DNA bond in a ping-pong reaction, and both are activated such that the attacking NE nitrogens contain the lone pair of electrons. To ensure that the reaction occurs in the correct sequence, the first attacking histidine is strongly activated by a glutamate, whereas the second histidine is weakly activated by a glutamine. A more in-depth biochemical analysis of a wider variety of site-directed mutants in the condensing enzyme active site will be required to determine if the two histidines have different roles in catalysis.

In the spFabF structure, there is a bound Mg2+ ion close to the Glu-Lys ion pair that is octahedrally coordinated to the OE1 of Glu 346, and the coordination shell is completed by Asn 301 OD1, Ser 391 OG, Asn 301 O, Ala 302 O, and Asn 392 O (Fig. 6A). This Mg2+ ion is not present in other structures of these enzymes, despite the existence of equivalent coordination sites. However, the presence of Mg2+ in our structure does not significantly distort the geometry of the residues involved in the coordination of the Mg2+ (Fig. 6B), nor does it alter the active site geometry (Fig. 5B). SpFabF retains full activity in buffers containing EDTA, indicating that Mg2+ does not have a role in catalysis. Mg2+ concentrations higher than 150 mM do progressively inhibit the activity of SpFabF, but this effect may be due to divalent cation interactions with ACP rather than the condensing enzyme. It is most likely that the presence of Mg2+ in the spFabF structure arises from the high concentration of this cation (250 mM) in the crystallization buffer.

The pseudodyad, a closer look.

A superposition of the two halves of the spFabF monomer, i.e., residues 1 to 250 (the N-terminal half) and residues 251 to 409 (the C-terminal half), highlights the similarity of the two folds, which clearly reflects a gene duplication event (see Fig. 3). In the case of spFabF, the root mean square deviation for the 84 superimposed carbon atoms is 1.8 Å, which indicates a high level of structural similarity. The regions outside of the duplicated areas fold into three highly structured lobes, two of which originate from the N-terminal region and one which originates from the C-terminal region. The two N-terminal lobes form key substrate recognition features that distinguish the elongation enzymes from the other two major classes of the thiolase superfamily. The lobe encompassing residues 107 to 138, which is insert 2 (I2), is labeled a in Fig. 3. In the complete structure, it interacts with its dimeric partner across the two-fold axis and together they create the pair of pockets that accommodate the acyl chains of the elongating lipid substrates (32, 35, 39). The second and largest lobe is labeled b in Fig. 3, and it encompasses two stretches of the protein, residues 15 to 70 (I1) and 194 to 233 (I3). They combine to create the pantetheine binding pocket that reaches down into the active site from the surface. The third lobe, labeled c in Fig. 3, is created by insert 4 (I4) and is located in the C-terminal domain. It is the shortest excursion from the duplicated fold and interacts with strand Cβ3. The residues within this lobe have no obvious mechanistic role, and it may simply represent a structural surrogate of the dimeric interaction that involves strand Nβ3 with itself across the two-fold axis.

Pantetheine binding.

The pantetheine binding site is located in the active site tunnel, which contains a number of residues that are strictly conserved in 23 of 23 FabF-FabB sequences examined. These are Ala 208, Gly 228, Thr 305, Thr 307, and Phe 396. Near the entrance to the tunnel are Ala 208 and Gly 228, whereas Thr 305 and Thr 307 are stacked on top of each other when looking down into the tunnel entrance, aligning themselves with the active site at the base of the tunnel. The conservation of these five residues and their location in this region of the protein suggest that they play an important role in binding the pantetheine moiety. We and others have observed the binding of a pantetheine moiety in the structures of FabH that form a complex with CoA (8, 38, 41). Using the common features of the FabH and spFabF substrate binding tunnels as a guide, we docked the pantetheine moiety from the FabH structures into our spFabF structure in order to identify potential roles for the conserved active site tunnel residues of FabB-FabF. A weakness of our model is that we are using the FabH-CoA structure to model the FabF-holo-ACP interactions. However, the model clearly suggests roles for the conserved residues in FabF and FabB. Ala 208 and Gly 228 form the entrance to the tunnel and are probably conserved to provide the necessary opening. Thr 305 and Thr 307 are in a position to form hydrogen bond interactions with the peptide groups of pantetheine, and Phe 396 makes hydrophobic interactions with the final two carbon atoms that are linked to the terminal sulfur atom. These interactions are predicted to clamp the end of the pantetheine and its attached substrate close to the active site. These latter hydrophobic interactions would mimic what occurs in the FabH structure through the interactions of Leu 198 (E. coli FabH sequence) with the pantetheine moiety.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM34496, Cancer Center (CORE) support grant CA21765, and the American Syrian Lebanese Associated Charities.

Data were collected at the SER-CAT 22-ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. SER-CAT-supporting institutions may be found at www.ser.anl.gov/new/index.html. The use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy, under contract no. W-31-109-Eng-38.

We thank Yon-Mei Zhang for the SpFabF enzymatic assays and the Protein Production Facility, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, for protein preparation and crystallization trials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee, A., E. Dubnau, A. Quémard, V. Balasubramanian, K. S. Um, T. Wilson, D. Collins, G. de Lisle, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1994. inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 263:227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunger, A. T., P. D. Adams, G. M. Clore, W. L. DeLano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J. S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54:905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collaborative Computation Project, Number 4. 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 50:760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Agnolo, G., I. S. Rosenfeld, J. Awaya, S. Omura, and P. R. Vagelos. 1973. Inhibition of fatty acid biosynthesis by the antibiotic cerulenin. Specific inactivation of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 326:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Agnolo, G., I. S. Rosenfeld, and P. R. Vagelos. 1975. Multiple forms of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 250:5289-5294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies, C., R. J. Heath, S. W. White, and C. O. Rock. 2000. The 1.8 Å crystal structure and active site architecture of β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase III (FabH) from Escherichia coli. Structure 8:185-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies, D. R., H. Interthal, J. J. Champoux, and W. G. Hol. 2002. The crystal structure of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase, Tdp1. Structure 10:237-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Mendoza, D., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1983. Thermal regulation of membrane lipid fluidity in bacteria. Trends Biochem. Sci. 8:49-52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas, J. D., S. J. Senior, C. Morehouse, B. Phetsukiri, I. B. Campbell, G. S. Besra, and D. E. Minnikin. 2002. Analogues of thiolactomycin: potential drugs with enhanced anti-mycobacterial activity. Microbiology 148:3101-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esnouf, R. M. 1999. Further additions to MolScript version 1.4, including reading and contouring of electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D 55:938-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrer, J.-L., J. M. Jez, M. E. Bowman, R. A. Dixon, and J. P. Noel. 1999. Structure of chalcone synthase and the molecular basis of plant polyketide biosynthesis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:775-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garwin, J. L., A. L. Klages, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1980. β-Ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II of Escherichia coli. Evidence for function in the thermal regulation of fatty acid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 255:3263-3265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heath, R. J., and C. O. Rock. 2002. The Claisen condensation in biology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19:581-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heath, R. J., S. W. White, and C. O. Rock. 2001. Lipid biosynthesis as a target for antibacterial agents. Prog. Lipid Res. 40:467-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath, R. J., Y.-T. Yu, M. A. Shapiro, E. Olson, and C. O. Rock. 1998. Broad spectrum antimicrobial biocides target the FabI component of fatty acid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30316-30321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopwood, D. A., and D. H. Sherman. 1990. Molecular genetics of polyketides and its comparison to fatty acid biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24:37-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, W., J. Jia, P. Edwards, K. Dehesh, G. Schneider, and Y. Lindqvist. 1998. Crystal structure of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II from E. coli reveals the molecular architecture of condensing enzymes. EMBO J. 17:1183-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackowski, S., and C. O. Rock. 1987. Acetoacetyl-acyl carrier protein synthase, a potential regulator of fatty acid biosynthesis in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 262:7927-7931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackowski, S., and C. O. Rock. 2002. Forty years of fatty acid biosynthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292:1155-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones, T. A., J. Y. Zou, S. W. Cowan, and M. Kjeldgaard. 1991. Improved methods for binding protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47:110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. McArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:282-291. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liscum, L. 2002. Cholesterol biosynthesis, p. 409-431. In D. E. Vance and J. E. Vance (ed.), Biochemistry of lipids, lipoproteins and membranes, 4th ed. Elsevier, New York, N.Y.

- 26.Mathieu, M., Y. Modis, J. P. Zeelen, C. K. Engel, R. A. Abagyan, A. Ahlberg, B. Rasmussen, V. S. Lamzin, W. H. Kunau, and R. K. Wierenga. 1997. The 1.8 Å crystal structure of the dimeric peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications for substrate binding and reaction mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 273:714-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuire, K. A., M. Siggaard-Andersen, M. G. Bangera, J. G. Olsen, and P. Wettstein-Knowles. 2001. β-Ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase I of Escherichia coli: aspects of the condensation mechanism revealed by analyses of mutations in the active site pocket. Biochemistry 40:9836-9845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMurray, L. M., M. Oethinger, and S. Levy. 1998. Triclosan targets lipid synthesis. Nature (London) 394:531-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merrit, E. A., and D. J. Bacon. 1997. Rasater 3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277:505-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, R., H. G. Gallo, H. G. Khalak, and C. M. Weeks. 1994. SnB: crystal structure determination via Shake-and-Bake. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 27:613-621. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moche, M., K. Dehesh, P. Edwards, and Y. Lindqvist. 2001. The crystal structure of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II from Synechocystis sp. at 1.54 A resolution and its relationship to other condensing enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 305:491-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moche, M., G. Schneider, P. Edwards, K. Dehesh, and Y. Lindqvist. 1999. Structure of the complex between the antibiotic cerulenin and its target, β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:6031-6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murshudov, G. N., A. A. Vagin, and E. J. Dodson. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D 53:240-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navaza, J. 1994. AMoRe—an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. A 50:869-873. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen, J. G., A. Kadziola, P. Wettstein-Knowles, M. Siggaard-Andersen, and S. Larsen. 2001. Structures of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I complexed with fatty acids elucidate its catalytic machinery. Structure 9:233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olsen, J. G., A. Kadziola, P. Wettstein-Knowles, M. Siggaard-Andersen, Y. Lindquist, and S. Larsen. 1999. The X-ray crystal structure of β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase I. FEBS Lett. 460:46-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otwinowski, Z., and W. Minor. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan, H., S. Tsai, E. S. Meadows, L. J. Miercke, A. T. Keatinge-Clay, J. O'Connell, C. Khosla, and R. M. Stroud. 2002. Crystal structure of the priming β-ketosynthase from the R1128 polyketide biosynthetic pathway. Structure 10:1559-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price, A. C., K. H. Choi, R. J. Heath, Z. Li, C. O. Rock, and S. W. White. 2001. Inhibition of β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthases by thiolactomycin and cerulenin: structure and mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 276:6551-6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu, X., C. A. Janson, A. K. Konstantinidis, S. Nwagwu, C. Silverman, W. W. Smith, S. Khandekar, J. Lonsdale, and S. S. Abdel-Meguid. 1999. Crystal structure of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III. A key condensing enzyme in bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36465-36471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qiu, X., C. A. Janson, W. W. Smith, M. Head, J. Lonsdale, and A. K. Konstantinidis. 2001. Refined structures of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III. J. Mol. Biol. 307:341-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rock, C. O., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1996. Escherichia coli as a model for the regulation of dissociable (type II) fatty acid biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1302:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenfeld, I. S., G. D'Agnolo, and P. R. Vagelos. 1973. Synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids and the lesion in fabB mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 248:2452-2460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakya, S. M., M. Suarez-Contreras, J. P. Dirlam, T. N. O'Connell, S. F. Hayashi, S. L. Santoro, B. J. Kamicker, D. M. George, and C. B. Ziegler. 2001. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of thiotetronic acid analogues of thiolactomycin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11:2751-2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scarsdale, J. N., G. Kazanina, X. He, K. A. Reynolds, and H. T. Wright. 2001. Crystal structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20516-20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulz, H. 2002. Oxidation of fatty acid in eukaryotes, p. 127-180. In D. E. Vance and J. E. Vance (ed.), Biochemistry of lipids, lipoproteins and membranes, 4th ed. Elsevier, New York, N.Y.

- 47.Smith, S. 1994. The animal fatty acid synthase: one gene, one polypeptide, seven enzymes. FASEB J. 8:1248-1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor, P., S. L. Pealing, G. A. Reid, S. K. Chapman, and M. D. Walkinshaw. 1999. Structural and mechanistic mapping of a unique fumarate reductase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:1108-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsay, J.-T., C. O. Rock, and S. Jackowski. 1992. Overproduction of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I imparts thiolactomycin resistance to Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 174:508-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vance, D. E., I. Goldberg, O. Mitsuhashi, K. Bloch, S. Omura, and S. Nomura. 1972. Inhibition of fatty acid synthetases by the antibiotic cerulenin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 48:649-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]