Abstract

The structure of the recombinant Escherichia coli protein YbcJ, a representative of a conserved family of bacterial proteins (COG2501), was determined by nuclear magnetic resonance. The fold of YbcJ identified it as a member of the larger family of S4-like RNA binding domains. These domains bind to structured RNA, such as that found in tRNA, rRNA, and a pseudoknot of mRNA. The structure of YbcJ revealed a highly conserved patch of basic residues, comprising amino acids K26, K38, R55, K56, and K59, which likely participate in RNA binding.

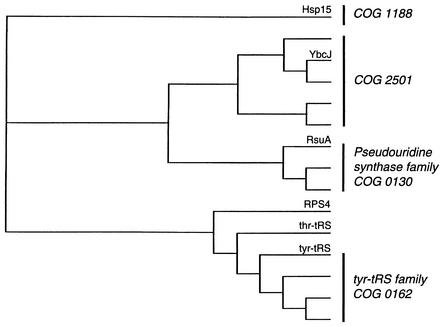

YbcJ is a 77-residue protein belonging to a large family of conserved bacterial proteins, classified in the COG2501 cluster of orthologous groups (1, 32). These proteins show distant sequence similarity with the larger family of ribosomal protein S4 domains, but with distinct features specific for this COG. S4 domains are usually present in larger proteins containing other functional domains, such as tyrosyl-tRNA and threonine-tRNA synthetases (tyr-tRS and thr-tRS, respectively), pseudouridine synthases, ribosomal proteins S4 (RPS4s), and methyltransferases (2) (see the phylogenic tree in Fig. 1). Recent structural work on complexes of S4 proteins with RNA, S4 in the ribosome (5) and tyr-tRS with tRNA (41) reveal the important role of S4 domains for binding specific structured conformations of RNA, such as those present in rRNA and tRNA. These interactions are further exemplified by the unique interaction of S4 with a nested pseudoknot mRNA structure spanning the ribosome binding site and regulating synthesis of a set of ribosomal proteins (29).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenic tree of the amino acid sequences of S4 domains. The amino acid sequences were aligned using the multiple alignment program CLUSTAL W (33). The tree was drawn with TreeView (24). The COG numbers for each group are indicated.

Proteins most similar to YbcJ (i.e., COG2501) are very small—approximately 80 amino acids long—and do not contain any additional recognizable functional domains. Their characteristic sequence motif, located in the C-terminal part, consists of E/D-x-R/K-R/K-x-x-K (ETRKRCK in YbcJ) and is likely related to a unique function of this subclass of S4 family proteins. Structural work on YbcJ was undertaken to investigate the relationship between proteins in COG2501 and the larger family of S4 proteins and to provide a structural basis for future functional studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of YbcJ.

The ybcJ gene was amplified by PCR using recombinant Taq polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) with Escherichia coli MC1061 genomic DNA as a template. The amplified insert was cloned into a modified pET20b vector (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) using BamHI-EcoRI restriction sites and transformed into the BL21 (DE3) strain of E. coli. The full-length construct includes an N-terminal His8 tag and a thrombin cleavage site. The expression of YbcJ was induced by 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 25°C for 18 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 35 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 8.0], 0.3 M NaCl, 1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 2 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 3.5 mg of lysozyme, and 250μg of DNase). Cells were disrupted by sonication, and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation. The supernatant containing YbcJ was loaded on a 1.5-ml column of Ni2+-loaded chelating Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and eluted with 0.2 M imidazole in phosphate buffer [pH 8.0] by using standard protocols. Isotopically enriched YbcJ was prepared from cells grown on minimal M9 media containing [15N]ammonium chloride with or without [13C6]glucose (Cambridge Isotopes Laboratory, Andover, MA). The His tag was cleaved by incubation for 18 h with 40 units of thrombin at 4°C and removed using the Ni2+ affinity column. The cleaved protein used for the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments contained two extra N-terminal residues (Gly-Ser) numbered −1 and 0.

NMR spectroscopy.

NMR samples contained 4 to 7 mM YbcJ in 50 mM phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl, 15 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.1 mM sodium azide at pH 6.8. NMR experiments were performed at 313 K on a Bruker DRX500 spectrometer, with the exception of the 1H-15N residual dipolar couplings, which were collected on a Bruker 600-MHz AVANCE spectrometer. Sequential backbone assignments were based on scalar couplings through the backbone (14) using HNCACB (39) and CBCA(CO)NH (11) experiments. Backbone assignments were checked using carbonyl chemical shift correlations from (H)CACOCANH (19) and HNCO (12) experiments and further confirmed by searching for characteristic sequential cross-peaks from the backbone amide proton to the preceding amide or a proton (40) in an 1H-15N NOESY-HMQC experiment. Carbon and proton assignments for the side chains were obtained from 1H-15N TOCSY-HMQC, C(CO)NH, and H(CCO)NH experiments (10). Spin systems for the aromatic rings were connected to the protein backbone via homonuclear DQF-COSY, TOCSY, and NOESY cross-peaks recorded in D2O. Chemical shifts were measured relative to internal 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) for 1H and calculated for 13C and 15N with the assumptions γ15N/γ1H = 0.101329118 and γ13C/γ1H = 0.251449530 (37). 1H-15N heteronuclear NOEs were measured at 313 K on YbcJ (26). NMR spectra were processed using XWINNMR (Bruker Biospin) and GIFA (27) software and analyzed with XEASY (3). 1H-15N residual dipolar couplings were determined from comparison of the 1JNH splittings of 15N-labeled YbcJ in an isotropic medium and an aligned medium containing ∼8 mg of Pf1 phage/ml using the IPAP-HSQC pulse sequence (23).

Structure calculations.

Structures were calculated using the ARIA module (22) implemented in the program CNS, version 1.1 (4). NOE restraints were obtained from an 1H-15N NOESY-HMQC experiment using a mixing time of 110 ms and from a two-dimensional NOESY experiment (110 ms mixing time) of unlabeled YbcJ recorded in D2O. Manually assigned distance restraints were classified according to the peak intensities as strong (1.8 to 3.0 Å), medium (1.8 to 4.0 Å), and weak (1.8 to 5.0 Å). Distance restraints assigned by ARIA were calibrated according to NOE peak volumes. Regions of regular α-helical and β-strand secondary structures were determined based on Cα, Hα, and CO chemical shifts (36, 38), sequential and medium-range NOE patterns, and values of 3JHNHα coupling constants derived from an HNHA experiment (17). From this latter experiment, 44 φ dihedral angles were obtained. For β-methylene protons, stereospecific assignments were determined from the strength of the 3JHαHβ coupling constants measured with a DQF-COSY experiment, and from the HNHβ and HαHβ NOE cross-peaks. Wherever β-methylene protons could be assigned stereospecifically, the χ1 angle was restrained to one of the staggered conformations (+60°, +180°, −60°) ± 60°. A total of 26 χ1 dihedral angles were found. Finally, a lyophilized sample of 15N-labeled YbcJ was dissolved in D2O, and 1H-15N HSQC experiments were recorded at 10-min intervals at 293 K. Amide protons were considered to exchange slowly and then to be involved in a hydrogen bond if they were still visible in spectra recorded 45 to 65 min after the addition of D2O. For each hydrogen bond, two distance restraints were applied: 1.5 to 2.3 Å for NH(i)-O(j) and 2.5 to 3.3 Å for N(i)-O(j).

An initial set of 600 cross-peaks from two-dimensional NOESY and three-dimensional 1H-15N NOESY-HMQC spectra were manually assigned. These NOEs, together with the 70 experimental dihedral angles (44 φ and 26 χ1, see above), were used in the ARIA protocol to calibrate and assign the unassigned NOE cross-peaks. After a first round in ARIA, about 320 additional NOE cross-peaks were unambiguously assigned. Fifty-six more were manually assigned. The resulting models were then used to identify hydrogen bonds. Twenty-seven hydrogen bonds were consistently observed, giving rise to 54 distance restraints. These assigned NOEs, hydrogen bonds, and torsion angles were then used in a second run of ARIA. Thirty additional distance restraints (NOEs) were then assigned. This ensemble of distance and dihedral restraints was used in a CNS structural calculation protocol starting with an extended molecule. From 50 structures calculated, the structure having the lowest energy and least violations was used as input for the TALOS program (8). TALOS derives information on the φ and ψ backbone dihedral angles from a comparison of secondary chemical shifts patterns of amino acid triplets against a database of secondary chemical shifts of known conformations. This calculation with TALOS generated 6 additional φ dihedral and 13 new ψ dihedral angle constraints. Finally, residual dipolar coupling restraints (34) were incorporated into the CNS calculations to generate a total of 60 conformers of YbcJ. The residual dipolar coupling alignment tensor was initially estimated from distribution of couplings (6) and further refined as described by Clore et al. (7). The final values used for axial and rhombic components of the alignment tensor were 14 for Da and 0.5 for R.

The quality of structures obtained was assessed using PROCHECK (18) without the unstructured residues 1 to 8. The graphic representations of the three-dimensional structures were performed using MOLMOL (15), GRASP (21), and MOLSCRIPT (16). Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/) under accession code 1P9K.

RESULTS

Resonance assignment.

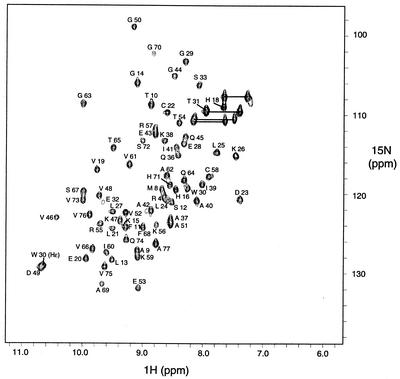

1H-15N HSQC spectrum of 15N-enriched YbcJ showed very good signal dispersion (Fig. 2). Sequence-specific resonance assignments were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Amide signals of residues 1 to 3, 5 to 7, 34, and 35 were absent. Essentially, all backbone and side chain proton signals were unambiguously assigned, including the side chain protons of Asn7, Pro17, Gly34, and Ala35. The Hη of Arg and ɛNH2 protons of Lys residues were not assigned.

FIG. 2.

Two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of 15N-enriched YbcJ from E. coli. The spectrum was acquired at 313 K in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), 300 mM NaCl. The 1H-15N cross-peaks are labeled with the assigned amino acid type and residue number. Cross-peaks corresponding to the asparagine and glutamine side chains are connected with a horizontal line.

Secondary structure.

The pattern of short- and medium-range NOEs and 3JHNHα coupling constants served to identify the secondary structural elements of YbcJ. A figure of the 3JHN-Hα and the NOE and chemical shift index data are available online (http://www.bri.nrc.ca/mcgnmr). The pattern of dNN(i, i+2), dαN(i, i+3), and dαN(i, i+4) NOE connectivities with 3JHNHα coupling constants smaller than 6 Hz indicated the presence of two α-helices (21 to 29 α1 and 38 to 46 α2). Characteristic long-range backbone NOE connectivities (i-j >4) and large coupling constants (>9 Hz) were used to defined β-strands. Based on this standard, five β-strands (9 to 11 β1, 47 to 49 β2, 50 to 52 β3, 64 to 68 β4, and 71 to 75 β5) were identified, with β2 to β3, β2 to β4, and β4 to β5 being antiparallel and β1 to β5 being parallel. The location and the extent of the secondary structural elements were further supported by the analysis of 13Cα, 1Hα, and 13CO secondary chemical shifts (36, 38).

Tertiary structure of YbcJ.

A total of 1,011 nonredundant interproton distance constraints, 89 dihedral restraints, and 51 residual 1H-15N dipolar couplings were used in the final round of calculations. The distribution of constraints by range is summarized in Table 1. From the 60 final structures calculated by CNS (see Materials and Methods), 20 structures with the lowest energy and least violations were chosen to represent the solution structure of YbcJ (Fig. 3). In this family, all NOE violations were less than 0.2 Å and dihedral violations were less than 2°. These 20 structures exhibit no significant deviations from ideal covalent geometry and satisfy both the experimental and geometric constraints with minimal violations.

TABLE 1.

Structure statistics of YbcJ

| Field and variable(s) | Value |

|---|---|

| Restraints for final structure calculations | |

| Total restraints used | 1,151 |

| Total NOE restraints | 1,011 |

| Intraresidue | 473 |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 223 |

| Medium range (1 < |i − j| = 4) | 90 |

| Long range (|i − j| > 4) | 162 |

| Hydrogen bond restraints | 54 |

| 15N-1H residual dipolar couplings | 51 |

| Dihedral angles restraints | 89 |

| φ dihedral angles | 50 |

| ψ dihedral angles | 13 |

| χ1 dihedral angles | 26 |

| Statistics for structure calculations (<SA>a) | |

| RMSD from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0021 ± 0.00011 |

| Angles (degrees) | 0.359 ± 0.0076 |

| Inproper (degrees) | 0.2840 ± 0.0108 |

| RMSD from experimental restraints: distances (Å)b | 0.0100 ± 0.0007 |

| Final energies (kcal · mol−1) | |

| Etotal | −199.7 ± 14.0 |

| Ebonds | 5.4 ± 0.6 |

| Eangles | 42.6 ± 1.8 |

| EvdWc | −340.5 ± 10.4 |

| ENOE | 7.6 ± 1.0 |

| Ecdih | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| EImpropoer | 7.4 ± 0.6 |

| Esani | 76.5 ± 8.9 |

| Coordinate precision (Å)(<SA> versus <SA>)d | |

| RMSD of backbone atoms (N, Cα, C) for residues 9-77 | 0.68 ± 0.15 |

| RMSD of all heavy atoms for residues 9-77 | 1.27 ± 0.20 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%)e | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 67.0 ± 2.8 |

| Residues in additional allowed regions | 29.4 ± 1.4 |

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 3.2 ± 1.2 |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 0.4 ± 0.7 |

| Analysis of residual dipolar couplings | |

| RMSD (Hz) | 2.398 ± 0.139 |

| Q factor | 0.1758 ± 0.0102 |

| Correlation coefficient | 0.1243 ± 0.0072 |

<SA> refers to the ensemble of the 20 structures with lowest energy from 60 calculated structures.

No distance restraint in any of the structures included in the ensemble was violated by more than 0.2 Å.

Repel = 0.8 for the final step of calculations.

RMSD between the ensemble of structures <SA> and the average structure of the ensemble <SA>.

Generated using PROCHECK on the ensemble of the 20 lowest-energy structures, residues 9-77.

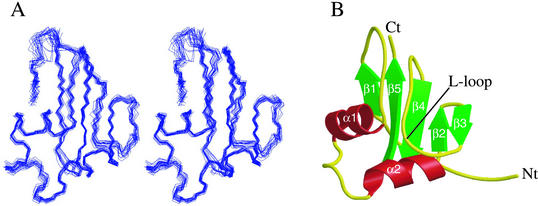

FIG. 3.

Three-dimensional solution structure of YbcJ. (A) Stereo view of 20 NMR models superimposed to minimize the RMSD of C, Cα, and N atom positions for residues 9 to 77. The residues 1 to 8 are not shown. (B) MOLSCRIPT (16) diagram of the backbone fold of the model closest to the geometric average. Nt and Ct indicate the N and C termini.

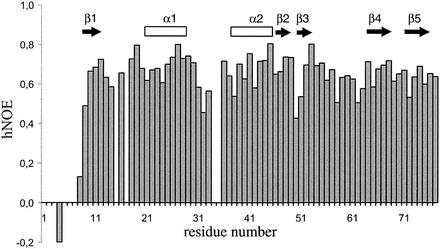

In the NMR ensemble of YbcJ, the regions comprising residues 13 to 15 and 50 to 51 are less well defined, and the first eight residues at the N terminus are completely disordered. This correlates with the lack of constraints in these regions and with the lower 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE values (Fig. 4). Although the value for residue 32 has a larger error due to the weakness of the signal in the HSQC spectrum (see Fig. 2), values between 0.46 and 0.58 were obtained for residues 31 to 33. This indicates that the region located between the two α-helices is relatively flexible, despite the fact that it appears quite structured in the final conformers. Unfortunately, no data are available for the N-terminal region (residues 1 to 3 and 5 to 7) and residues 34 and 35, since they were not detected in 1H-15N HSQC spectra. When calculated with residues 9 to 77, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the 20 structures with respect to the mean coordinate positions is 0.68 and 1.27 Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively. The backbone heteronuclear NOE values for the structured regions are all positive, and most range between 0.6 and 0.8 (Fig. 4), which is in good agreement with the structural model (Fig. 3). In the calculated ensemble, 67.0% of residues were in the most favored region on Ramachandran plot using the software program PROCHECK; 29.4% were in the additionally allowed region, 3.2% were in the generously allowed region, and 0.4% were in the disallowed region. The residues located in the two latter regions are mostly located in flexible regions or connect secondary structural elements. The structural statistics for the 20 structures are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 4.

Heteronuclear NOEs (hNOE) for backbone amide nitrogens measured at a proton frequency of 500 MHz. Secondary structural elements are indicated as arrows (β-strands) and open rectangles (α-helices).

The protein YbcJ folds into an α+β structure with five β-strands on one side and two α-helices on the opposite side of the molecule. The two α-helices consist of approximately two turns (residues 21 to 29 and 38 to 46 for α1 and α2, respectively). Extended strands 2 to 3 and 4 to 5 form two adjacent β-hairpins where strand 2 is antiparallel to strand 4, while the strand 1 is parallel to the strand 5 (see the ribbon diagram in Fig. 3B). A total of 14 hydrogen bonds stabilize this well-defined β-sheet. The loop between the strands 3 and 4 forms an L-shaped loop (residues 53 to 61) which is located on the same side as the two α-helices. This L-loop interacts with the beginning of the first α-helix by forming a hydrogen bond between HN of residue 19 and CO of residue 60. The φ and ψ dihedral angles for residues 19, 20, 60, and 61 are quite consistent for an antiparallel β-sheet.

The amide protons implicated in all these hydrogen bonds were found to slowly exchange with D2O. Specifically, these were amide protons in β-sheet residues 11, 13, 47, 48, 49, 51, 64, 66, 67, 68, 73, 74, 75, and 76 and α-helical residues 24 to 30 and 42 to 46. This was also the case for the amide protons of residues 19 and 64, which are hydrogen bonded with the carbonyl groups of residues 60 (see above) and 62, respectively. The 64 HN-62 CO hydrogen bond, which forms a γ-turn, was not restrained in the structure calculation.

Hydrophobic contacts involving the residues F11, L13, V19, L21, L24, L25, V48, A51, C58, I60, V66, V73, and V75 form a hydrophobic core, which stabilizes the folding and structural integrity of the molecule. This hydrophobic core also involves side chains of the three residues W30 (end of the α1 helix), F68, and H71 (turn of the second β-hairpin β4-β5) that form an aromatic stacking.

Finally, additional hydrogen bonds were observed in almost all the final structures and contribute to the stability of different parts of YbcJ: E22 (HN)—D25 (Oδ) (17 of 20 structures) and H71 (HN)—A69 (O) (18 of 20 structures). These amide protons also slowly exchanged but they were not visible 45 min. after addition of D2O.

DISCUSSION

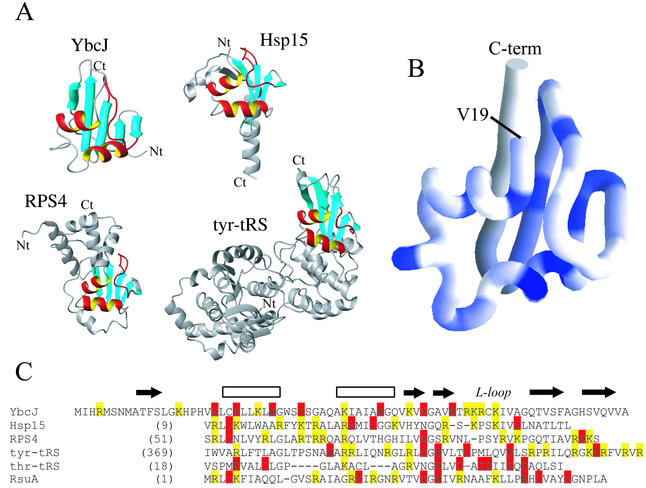

X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy have provided three-dimensional structures of a number of S4-family RNA binding domains: protein S4 of the 30S ribosomal subunit RPS4 (9, 20), heat shock protein Hsp15 (31), thr-tRS (28), tyr-tRS (41) and the pseudouridine synthase RsuA (30), which catalyzes formation of pseudouridine (ψ) in the 16S rRNA. Despite the relatively low sequence similarity among the S4 domains of these proteins (Fig. 5C), they are folded similarly, especially around the centers of the domain (Fig. 5A). These structures show significant Dali Z scores (3.4, 4.9, 5.3, 2.6, and 3.8, respectively) against YbcJ (13). A score of 2.0 or more indicates significant similarity. The common secondary structures are two α-helices and the three following β-strands, the first two of which form a small β-hairpin. This distinct structural motif (in particular, the two helices and adjacent loop highlighted in red in Fig. 5A) is termed the αL motif (31). Analysis of the sequences of S4 domains shows that the most highly conserved residues are buried and populate the interface between the different elements forming the αL motif (Fig. 5B). Residues of the first β-hairpin, β2-β3, are also highly conserved and probably important for the folding and stability of the αL motif.

FIG. 5.

(A) The peptide backbone folds of three different S4 family proteins are compared with YbcJ. The PDB codes are 1DM9 for Hsp15 (31), 1C05 for RPS4 (20), and 1H3E for tyr-tRS (41). In these proteins, the fragment corresponding to the YbcJ, αL motif, and β-sheet is highlighted, while the rest of the molecule is in gray (the L-loop is red). Nt and Ct indicate N-terminal and C-terminal positions. (B) Representation of the YbcJ backbone from residues 19 to 77 generated with GRASP (21). The backbone trace is color-coded according to the similarity of the residues of YbcJ compared with the sequences of 50 S4/Hsp/tRNA synthetase RNA-binding domains in the Conserved Domain Database (gnl|CDD|12100). Residues having low similarity are shown in white, while those having high similarity are blue. The orientation is the same as in Fig. 3. (C) Structure-based sequence alignment of the proposed αL RNA-binding motif in the proteins presented in the text. The first four proteins are presented in panel A. The secondary structure is shown above the sequence alignment. Positively and negatively charged residues are shown in yellow and red, respectively.

Recently, two structures of S4 domains bound to RNA were reported. These are the entire 30S ribosomal subunit (PDB code 1FJG) (5) and the tyr-tRS (PDB code 1H3E) (41). In both structures, the αL motif was found to interact with a double-stranded RNA. However, one can remark that the surfaces involved in this contact are not exactly the same. For tyr-tRS, the residues that interact with RNA are on the helix α2 (S383, R389, N393, and R394) and the turn of the second β-hairpin, β4-β5 (R420, K422, D423, and R424). For the RPS4, in addition to α2 helix (S113, R115, Q116, R118, Q119, R122, and H123), the L-shaped loop contributes to this interaction (R131, R132, D134, and R139).

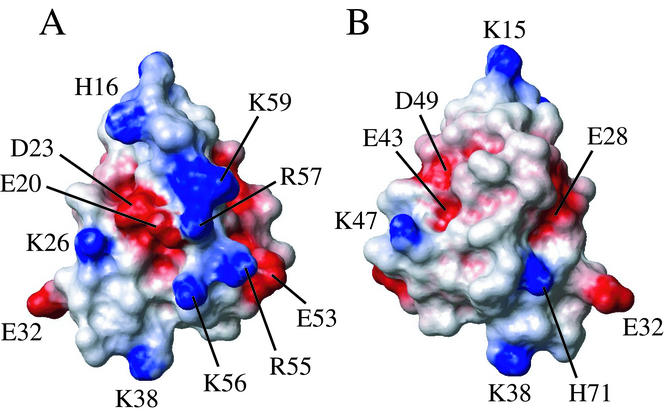

We analyzed the distribution of charged residues in YbcJ to look for a potential RNA binding surface. Regions with a high concentration of positive charges are essential for interactions with the negatively charged phosphate backbone of RNA (25, 35). In YbcJ, side chains of K38 on α2 and R55, K56, R57, and K59 on the L-shaped loop cluster to form a positively charged surface in the αL motif (Fig. 6A). On the same face, the α1 helix exposes another positive side chain (K26) but also exposes two negatively charged residues (E20 and D23) in the middle of this basic area. The positively charged residues K26, K38, R55, K56, and K59 are strongly conserved in proteins from COG2501, suggesting that this is a conserved feature of this subfamily of bacterial proteins. The opposite face of YbcJ is relatively hydrophobic (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

(A and B) Potential map of the surface of YbcJ, calculated with MOLMOL (15). Two orientations, related by a 180° rotation along a vertical axis, are shown. The orientation of panel A is the same as that of Fig. 3 and 5. Residues 1 to 7 were removed for clarity. The surfaces are color coded, with red indicating net negative electrostatic potential and blue indicating positive potential.

A comparison of potential maps of the surface of YbcJ with Hsp15, RPS4, thr-tRS, tyr-tRS, and RsuA reveals important differences in the distribution of charged residues. In particular, the positively charged surface is not always at the same place in the S4 domain. In Hsp15 and RPS4, the positive charges are essentially clustered around the α2 helix and the L-loop, which corresponds to the binding site of RNA by RPS4. In RsuA, five positive residues on α1 and α2 helices define the basic surface. In tyr-tRS, the positive surface is on helix α2 and the turn of the second β-hairpin, β4-β5. Finally, thr-tRS was crystallized with RNA, but no interactions were observed between the S4 domain and the RNA. The αL motif in thr-tRS is highly negative, with eight negatively and only two positively charged residues. Although, structurally, YbcJ is most similar to tyr-tRS, which has the highest DALI Z score (Fig. 5), the distribution of charged residues looks more like RPS4 and Hsp15 and, to a lesser extent, RsuA. We hypothesize that the YbcJ would bind RNA in the same way as RPS4 and Hsp15, i.e., on the side comprising the helix α2 and the L-loop. Extrapolation from the various S4 family members would suggest that YbcJ interacts with structured or double-stranded RNA.

In conclusion, YbcJ possesses a number of structural and sequence properties of the RNA-binding proteins of the S4 superfamily. The solution structure of YbcJ reveals the presence of an αL motif, rich in positive charged residues (arginines and lysines), which may function to bind RNA. Functional studies of YbcJ are currently in progress to delimit the RNA-binding surface and residues involved.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Montreal-Kingston Bacterial Structural Genomics Initiative under a CIHR Genomics grant to M.C., I.E., and K.G.

We thank Christophe Deprez for preparing a script converting BLAST data into GRASP format.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 1999. Novel predicted RNA-binding domains associated with the translation machinery. J. Mol. Evol. 48:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartels, C., T.-H. Xia, M. Billeter, P. Güntert, and K. Wüthrich. 1995. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 5:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunger, A. T., P. D. Adams, G. M. Clore, W. L. DeLano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J.-S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54:905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter, A. P., W. M. Clemons Jr., D. E. Brodersen, B. T. Wimberly, R. Morgan-Warren, and V. Ramakrishnan. 2000. Functional insights from the structure of the 30S ribosomal subunit and its interactions with antibiotics. Nature 407:340-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clore, G. M., A. M. Gronenborn, and A. Bax. 1998. A robust method for determining the magnitude of the fully asymmetric alignment tensor of oriented macromolecules in the absence of structural information. J. Magn. Reson. 133:216-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clore, G. M., A. M. Gronenborn, and N. Tjandra. 1998. Direct refinement against residual dipolar couplings in the presence of rhombicity of unknown magnitude. J. Magn. Reson. 131:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornilescu, G., F. Delaglio, and A. Bax. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13:289-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies, C., R. B. Gerstner, D. E. Draper, V. Ramakrishnan, and S. W. White. 1998. The crystal structure of ribosomal protein S4 reveals a two-domain molecule with an extensive RNA-binding surface: one domain shows structural homology to the ETD DNA-binding motif. EMBO J. 17:4545-4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grzesiek, S., J. Anglister, and A. Bax. 1993. Correlation of backbone amide and aliphatic side-chain resonances in C-13/N-15-enriched proteins by isotropic mixing of C-13 magnetization. J. Magn. Reson. 101:114-119. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grzesiek, S., and A. Bax. 1992. Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:6291-6293. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grzesiek, S., and A. Bax. 1992. Improved 3D triple-resonance NMR techniques applied to a 31 kDa protein. J. Magn. Reson. 96:432-440. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holm, L., and C. Sander. 1993. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 233:123-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay, L. E., M. Ikura, R. Tschudin, and A. Bax. 1990. Three-dimensional triple resonance NMR-spectroscopy of isotopically enriched proteins. J. Magn. Res. 89:496-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koradi, R., M. Billeter, and K. Wüthrich. 1996. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuboniwa, H., S. Grzesiek, F. Delaglio, and A. Bax. 1994. Measurement of HN-Hα J couplings in calcium-free calmodulin using new 2D and 3D water-flip-back methods. J. Biomol. NMR 4:871-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohr, F., and H. Ruterjans. 1995. A new triple-resonance experiment for the sequential assignment of backbone resonances in proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 6:189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markus, M. A., R. B. Gerstner, D. E. Draper, and D. A. Torchia. 1999. Refining the overall structure and subdomain orientation of ribosomal protein S4 delta 41 with dipolar couplings measured by NMR in uniaxial liquid crystalline. J. Mol. Biol. 292:375-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholls, A., K. A. Sharp, and B. Honig. 1991. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins 11:281-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilges, M., M. J. Macias, S. I. O'Donoghue, and H. Oschkinat. 1997. Automated NOESY interpretation with ambiguous distance restraints: the refined NMR solution structure of the pleckstrin homology domain from beta-spectrin. J. Mol. Biol. 269:408-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ottiger, M., F. Delaglio, and A. Bax. 1998. Measurement of J and dipolar couplings from simplified two-dimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 131:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page, R. D. M. 1996. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel, D. J. 1999. Adaptive recognition in RNA complexes with peptides and protein modules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9:74-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng, J. W., and G. Wagner. 1994. Investigation of protein motions via relaxation measurements. Methods Enzymol. 239:563-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pons, J. L., T. E. Malliavin, and M. A. Delsuc. 1996. Gifa V.4: a complete package for NMR data set processing. J. Biomol. NMR 8:445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sankaranarayanan, R., A. C. Dock-Bregeon, P. Romby, J. Caillet, M. Springer, B. Rees, C. Ehresmann, B. Ehresmann, and D. Moras. 1999. Crystal structure of E. coli threonyl-tRNA synthetase, a translational repressor enzyme with an essential catalytic zinc, complexed with its tRNA. Cell 97:371-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlax, P. J., K. A. Xavier, T. C. Gluick, and D. E. Draper. 2001. Translational repression of the Escherichia coli α operon mRNA: importance of an mRNA conformational switch and a ternary entrapment complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38494-38501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sivaraman, J., V. Sauve, R. Larocque, E. A. Stura, J. D. Schrag, M. Cygler, and A. Matte. 2002. Structure of the 16S rRNA pseudouridine synthase RsuA bound to uracil and UMP. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staker, B. L., P. Korber, J. C. Bardwell, and M. A. Saper. 2000. Structure of Hsp15 reveals a novel RNA-binding motif. EMBO J. 19:749-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatusov, R. L., D. A. Natale, I. V. Garkavtsev, T. A. Tatusova, U. T. Shankavaram, B. S. Rao, B. Kiryutin, M. Y. Galperin, N. D. Fedorova, and E. V. Koonin. 2001. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:22-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjandra, N., J. G. Omichinski, A. M. Gronenborn, G. M. Clore, and A. Bax. 1997. Use of dipolar 1H-15N and 1H-13C couplings in the structure determination of magnetically oriented macromolecules in solution. Nature Struct. Biol. 4:732-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varani, G. 1997. RNA-protein intermolecular recognition. Acc. Chem. Res. 30:189-195. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wishart, D. S., and B. D. Sykes. 1994. The 13C chemical shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical shift data. J. Biomol. NMR 4:171-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wishart, D. S., C. G. Bigam, J. Yao, F. Abildgaard, H. J. Dyson, E. Oldfield, J. L. Markley, and B. D. Sykes. 1995. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift references in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 6:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wishart, D. S., B. D. Sykes, and F. M. Richards. 1992. The chemical shift index: a fast and simple method for the assignment of protein secondary structure through NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 31:1647-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wittekind, M., and L. Mueller. 1993. HNCACB, a high sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amise-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha and beta carbon resonances with the alpha and beta carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. B 101:201-205. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wüthrich, K. 1986. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 41.Yaremchuk, A., I. Kriklivyi, M. Tukalo, and S. Cusack. 2002. Class I tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase has a class II mode of cognate tRNA recognition. EMBO J. 21:3829-3840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]