Structural genomics efforts worldwide have the goal of determining large numbers of protein structures in order to complement the ever-expanding database of genome sequences. Currently, some 87 bacterial genomes have been sequenced and another 125 are in progress (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMGifs/Genomes/micr.html). While structural genomics projects worldwide vary in their specific objectives, nearly all have two common themes. One is to develop high-throughput technologies for gene cloning, protein expression and purification, protein crystallization, structure determination, and overall data management (33). These technologies, when integrated, will allow implementation of a protein structure pipeline with a minimum of manual intervention. The other objective is, through target selection, to generate new biological insights into how proteins function at the atomic level. Most structural genomics initiatives currently under way (see http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/strucgen.html for a summary) focus on the genomes of prokaryotes, as the protein complement of these organisms is more tractable to high-throughput analysis than is currently the case with eukaryotes.

E. COLI AS A MODEL SYSTEM FOR STRUCTURAL GENOMICS

Among bacteria, Escherichia coli has been considered a model organism and has historically been the focus of many studies. Many decades of research have resulted in a wealth of genetic, biochemical, and structural information that together is unparalleled in other systems. Several efforts are currently under way worldwide to integrate this information in a “systems biology” approach to understanding E. coli at the whole-cell level, such as Project CyberCell (http://www.projectcybercell.com). Interest has also developed in simulating cell behavior in silico, as is being done, for example, with the Mycoplasma genitalium E-CELL project (68). Structural information on the E. coli proteome will be an important component of such projects.

Several full E. coli genome sequences have been determined, including those for E. coli K-12 (8), the hemorrhagic strains O157:H7 EDL933 (48) and O157:H7 (Sakai) (22), and the uropathogenic strain CFT073 (70). The availability of these genome sequences has spurred a more detailed analysis of the E. coli proteome, with techniques including microarrays (54, 63, 67), systematic gene knockouts, and high-resolution two-dimensional gels (35, 69). As well, the availability of the full genome sequences has provided the opportunity to utilize a number of in silico approaches to analysis of the proteome, including protein-protein interaction mapping (72) and protein evolution classification and divergence (34, 44).

FUNCTIONAL AND STRUCTURAL INFORMATION FOR THE E. COLI PROTEOME

As of 2001, a significant number (≈20%, or 862 of 4,285) of the E. coli protein-encoding genes had no assigned function (55). Approximately 50% of the proteins from E. coli have an experimentally verified function, with another 29.5% having an imputed function based on sequence similarity. Up-to-date functional and biochemical information on the E. coli genome can be obtained through the GenProtEC database (http://genprotec.mbl.edu/;) (50). A comparatively greater deficiency in functional information exists for the proteomes of the O157:H7 and CFT073 strains of E. coli, in which many proteins not common to E. coli K-12 have unknown functions. One role that structural genomics can and will have is to help assign and verify functions for these proteins, in combination with other biochemical approaches (75, 76). Even where function has been tentatively assigned, based mainly on sequence similarity to a sequence or sequences of defined function, errors in functional assignment can result (10). A further complication is that sequence-related proteins, in some instances, can have divergent functions (44).

Another role of structural genomics is to delineate the correspondence between sequence and structure space; a number of protein structures from otherwise unrelated (i.e., 8 to 10% sequence identity) families turn out to have remarkably similar folds (51). The current estimate is that ≈1,000 predominant protein folds account for the great majority of protein sequence families, with structural examples available for about half of these (31).

The extent of known and predicted structural information for the E. coli proteome can be described in different ways. Currently, 378 structures of E. coli proteins have been deposited within the Protein Data Bank (PDB [6]). Comparison of the sequences for E. coli proteins against PDB sequences with ψ-Blast with a threshold E-value of 0.001 yields an estimated 46.6% (1,997 of 4,289) of E. coli K-12 proteins and 41.7% (2,228 of 5,349) of E. coli O157:H7 proteins with at least some portion of assigned structure within the FAMSBASE protein modeling database (74). As part of current international structural genomics efforts, ≈50 protein structures have been determined from E. coli and deposited within the PDB, including many of those shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of structures determined

| Protein | Functiona | Resolution (Å) | Rwork/Rfree (%) | Ligand | PDB code | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoeA | Molybdopterin biosynthesis protein MoeA | 2.2 | 22.6/27.7 | Mg(H2O)6 | 1FC5 | 53 |

| Kb1 | 2-Amino-3-ketobutyrate CoA ligase | 2.0 | 15.1/20.6 | External aldimine | 1FC4 | 52 |

| HisC | l-Histidinol phosphate aminotransferase | 1.5 | 20.5/21.9 | PMP | 1FG7 | 57 |

| 2.2 | 21.3/25.7 | PLP | 1IJI | |||

| 2.2 | 20.2/22.1 | PLP-l-histidinol | 1FG3 | |||

| HisD | l-Histidinol dehydrogenase | 1.75 | 19.0/22.5 | None | 1K75 | 4 |

| 1.7 | 21.3/24.1 | l-Histidinol, Zn2+, NAD+ | 1KAE | |||

| 2.1 | 25.2/28.6 | l-Histidine, Zn2+, NAD+ | 1KAR | |||

| 2.1 | 24.8/28.1 | l-Histamine, Zn2+, NAD+ | 1KAH | |||

| RsuA | 16S rRNA pseudouridine synthase | 2.0 | 21.7/26.2 | Uracil | 1KSK | 58 |

| 2.65 | 21.3/25.6 | UMP | 1KSV | |||

| RlmB | 23S rRNA 2′-O-methyltransferase | 2.5 | 22.9/27.9 | None | 1GZ0 | 41 |

| YciO | Putative ssRNA binding | 2.1 | 21.2/22.9 | SO4 | 1KK9 | 27 |

| RpiA | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase | 2.5 | 22.7/27.0 | None | 1LKZ | 49 |

| RffH | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidyltransferase | 2.6 | 22.3/28.4 | dTTP/Mg2+ | 1MC3 | 59 |

| YebC | Unknown | 2.2 | 27.3/31.7 | None | 1KON | NA |

| CoaE | Dephosphocoenzyme A kinase | 1.8 | 21.0/24.5 | None | 1N3B | 47 |

| YdiB | Shikimate/quinate dehydrogenase | 2.5 | 22.6/29.4 | NAD+/PO3− | 1O9B | 41a |

| PdxA | 4-Hydroxythreonine-4-phosphate dehydrogenase | 2.0 | 22.1/26.9 | Zn2+/PO43− Zn2+/4-hydroxy- threonine-4-phosphate | NAb | |

| AgP | Glucose-1-phosphatase | 2.4 | 21.8/28.4 | Glucose-1-phosphate | 1NT4 | D. C. Lee et al., submitted for publication |

| Tig | Trigger factor, PPIase domainc | None | 1L1P | G. Kozolv et al., unpublished results | ||

| YbcJ | Putative RNA bindingc | None | 1O09 | 69a | ||

| MTH245 | Phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase | 1.7 | 21.5/24.5 | Cd2+ | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: CoA, coenzyme A; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; PPIase, peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase.

NA, not available.

Structure determined by nuclear magnetic resonance.

MONTREAL-KINGSTON BACTERIAL STRUCTURAL GENOMICS INITIATIVE

A unified view of the biology of any cell will require information on the structural components of the cell. A considerable amount of protein structural information has accumulated on the E. coli proteome, both from various independent laboratories and from current structural genomics projects worldwide. As part of the Montreal-Kingston Bacterial Structural Genomics Initiative (http://euler.bri.nrc.ca/brimsg/bsgi.html), genes have been selected from both E. coli K-12 and O157:H7 for structure determination. Proteins under study include those of both known and unknown function, with the emphasis on enzymes from small-molecule metabolic pathways (65), putative RNA binding proteins, and proteins that may play a role in bacterial pathogenesis. To date, a total of 17 structures have been determined by X-ray or nuclear magnetic resonance methods from this project and are summarized in Table 1. These structures shed light on a range of important biological processes in E. coli, ranging from the synthesis of histidine to binding and modification of rRNA to carbohydrate metabolism.

In the following we describe three examples of biological processes for which the structures determined provide new insights into and understanding of the molecular mechanisms at work in the cell.

HISTIDINE BIOSYNTHESIS

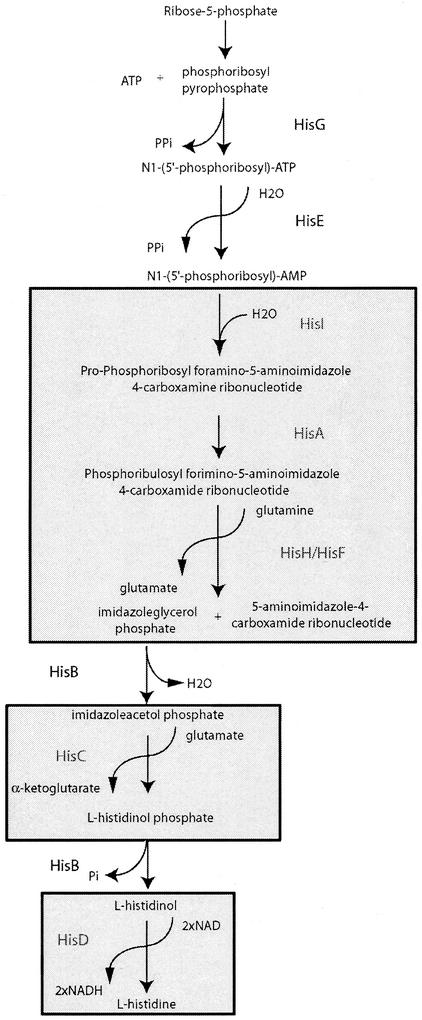

The histidine biosynthesis pathway has served as a paradigm for understanding a number of key processes in E. coli, including enzyme regulation by feedback control and genetic regulation. This pathway consists of 10 enzymatic steps, catalyzed by eight enzymes, beginning with ribose-5-phosphate and phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (reviewed in references 1 and 71). Two of these eight enzymes, HisI/E (11) and HisB (9), are bifunctional in eubacteria, while one, HisH/F, is a heterodimer (30). Despite this wealth of biochemical and genetic information, little was known about the structures of the enzymes in this pathway. Several initial targets from the project included enzymes from the histidine biosynthesis pathway, including HisA, HisI, HisC, HisD, and HisG.

The first crystal structures for enzymes in this pathway were reported for HisA and HisF from Thermotoga maritima (32). Subsequently, we (57) and concurrently others (21) independently determined the structure of E. coli HisC. The structures of the HisH/HisF heterodimeric enzyme from Thermus thermophilus HB8 (46) and Thermotoga maritima (17) as well as the isolated HisF subunit from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (12) and Pyrobaculum aerophilum (3) have recently been reported. This was followed by the structure of E. coli HisD (4). A report on the crystallization of E. coli HisG has been made (36), and its structure has been determined, although it has not yet been reported in the literature. A schematic view of the histidine biosynthesis pathway with the enzymes of known structure highlighted is presented in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Histidine biosynthesis pathway of E. coli (71). Steps in the pathway for which enzyme structures have been determined are shown in shaded boxes.

HisI. Our attempts to crystallize E. coli HisI/E, a bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the second and third steps, respectively, in the histidine biosynthesis pathway, were unsuccessful. However, we were able to crystallize phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase (EC 3.5.4.19) from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, a protein that is homologous to the N-terminal half of E. coli HisI and catalyzes the third step in this pathway. The HisI enzyme from Methanococcus vannielii has been best characterized biochemically, is a possible Zn2+ metalloprotein, and is Mg2+ activated (14).

Each monomer of HisI consists of a four-stranded mixed β-sheet, with an α-helix on the face of the β-sheet opposite the dimer interface. Interaction between the two HisI monomers forms the dimer interface by extending the mixed β-sheet from four to six strands, burying about 40% of the surface area of each monomer. A metal binding site is formed at the dimer interface, consisting of three Cys residues. This site is occupied by a Cd2+ ion in the structure determined but probably represents the expected Zn2+-binding site of HisI.

rRNA BINDING AND MODIFICATION

rRNA undergoes processing by a number of enzymes during maturation. While in many cases the precise functions of these modifications are not understood, the locations of these modifications often cluster to functionally important sites within the ribosome structure and therefore presumably influence ribosome function (reviewed in reference 15). Two of the most common modifications are conversion of uridine to pseudouridine (5-β-d-ribofuranosyl; ψ), a reaction catalyzed by pseudouridine synthases, or methylation of the ribose (2′OH) moiety or the base at various positions, as catalyzed by a variety of rRNA methyltransferases.

RsuA. Bacterial pseudouridine synthases have been grouped into four families based on sequence similarities, with the families being designated by one protein from each of the groups. These are designated TruA, TruB, RluA, and RsuA (summarized in reference 16). E. coli possesses a total of 10 pseudouridine synthases that modify uracil bases at 17 positions in tRNA as well as large-subunit 23S and small-subunit 16S rRNAs (16). Despite the lack of overall sequence similarity for these enzymes, a common feature of them all is a strictly conserved, catalytically essential Asp residue (25).

Relatively little structural information is available for pseudouridine synthases. Prior to structure determination of RsuA, the structure of the tRNA-specific ψ-synthase TruA from E. coli has been reported (18a). Concurrent with the structure determination of RsuA, the structure of E. coli TruB bound to an RNA T stem-loop was reported (23).

RsuA catalyzes the specific formation of ψ516, the only pseudouridine in 16S rRNA (13, 73). As this enzyme acts preferentially on an RNA fragment (bases 1 to 678) complexed with 30S proteins but neither free 16S rRNA nor intact 30S particles, it has been suggested that RsuA acts during an intermediate stage during ribosome assembly (73). Analysis of an E. coli MG1655 or BL21(DE3) rsuA strain did not show any influence on bacterial growth in either minimal or rich medium at a variety of temperatures, indicating that RsuA is not essential under ordinary physiological conditions (13).

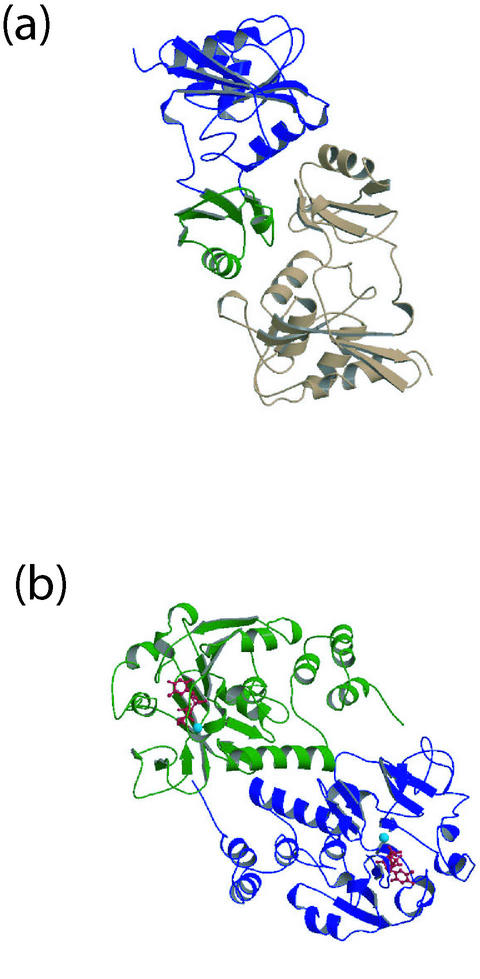

The crystal structure of E. coli RsuA was determined for the enzyme bound to either uracil or UMP (58). The structure revealed three domains, with the N-terminal domain connected to the central and C-terminal domains by an extended six-residue linker (Fig. 3a). The N-terminal domain shows both sequence similarity (2) and structural similarity to a family of RNA-binding domains having the αL structural motif, including those from ribosomal protein S4 and ribosome-associated heat shock protein Hsp15 (62). Based on this structural similarity, we proposed a model for how this domain may function by binding to RNA and correctly position the catalytic module of RsuA.

FIG.3.

Structures of E. coli rRNA binding and processing proteins. (a) Pseudouridine synthase RsuA (PDB code 1KSV), consisting of the rRNA-binding domain (blue) and catalytic module (green) bound to UMP (red). This structure (58) and its comparison with the structure of TruA (18) and the sequences of other pseudouridine synthases revealed a conserved fold for the catalytic module and similar active site for the four families of these enzymes. (b) The small conserved RNA-binding protein YbcJ (PDB code 1O09). The overall structure of this protein contains the αL motif (62) and resembles that of a domain of ribosomal protein S4. (c) 23S rRNA 2′-O-methyltransferase RlmB dimer (PDB code 1GZ0), with the rRNA-binding domain (blue) and catalytic domain (green) depicted. The rRNA-binding domain resembles that of ribosomal proteins L7 and L30, while the C-terminal domain containing the active site displays a novel methyltransferase fold with a deep knot (41).

The catalytic module of RsuA consists of a 170-residue-long segment comprising the central and C-terminal domains. This module contains a central β-sheet that spans both domains and is found to be structurally conserved in both TruA and TruB. Superposition of these modules also indicates a common active site cleft and a similar position for the catalytic Asp residue (Asp102 in RsuA). Together, these results suggest a common evolutionary origin for the bacterial pseudouridine synthases, which may have diverged from a common ancestor.

Two catalytic mechanisms have been proposed for pseudouridine synthases, like that found in either glycoside hydrolases or a Michael addition reaction (25). A series of elegant studies with 5-fluorouracil-tRNA led to the conclusion that the Michael addition mechanism is most probable (20). This conclusion has not been completely substantiated by the structural studies, one reason being the absence of additional residues at the active site that could participate in acid-base catalysis (42).

YbcJ. The structure of E. coli YbcJ, a member of a large family of sequence-related proteins (COG2501), has been determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (69a). This protein adopts an α+β fold (Fig. 3b) similar to that found in small ribosomal protein S4 and related domains found in larger proteins, including RsuA (58). While the specific function of YbcJ is currently unknown, it most likely plays a role in binding to structured RNA, such as tRNA, rRNA, or the pseudoknot of mRNA.

RlmB. Various RNA molecules, including rRNA and mRNA, are modified by methylation, either as part of maturation or for regulatory purposes. The rRNA of E. coli is no exception, with one 2′-O-methylation and nine base methylations within the 16S rRNA and three 2′-O-methylations and 11 base methylations within the 23S rRNA (15). Of the methylatated ribose moieties of 23S rRNA, three, at G2251, C2498, and U2552, occur in the peptidyltransferase region (60). Methylation of G2251 in E. coli is carried out by the enzyme RlmB, a 2′-O-methyltransferase that uses S-adenosylmethionine as the methyl donor (37). Deletion of the rlmB gene is not lethal, indicating that it is not essential for ribosome maturation. It is interesting that this protein was previously annotated as a putative methyltransferase (YjfH) of unknown function and that its function was defined (37) at nearly the same time that its structure was determined. This is likely to be a trend that will continue in the future and suggests that determining the structures of proteins of currently unknown function should not be a deterrent to researchers.

The structure of E. coli RlmB revealed a dimeric enzyme, with each 29-kDa monomer consisting of two domains connected by an extended linker (Fig. 3c) (41). The smaller domain adopts an α/β fold and resembles the structures of ribosomal proteins L7 and L12 from Haloarcular marismortui and L30 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The larger domain has an α/β/α architecture and resembles a Rossmann fold. The structural organization of RlmB has parallels to that of RsuA in that the N-terminal domain is relatively small and appears to function specifically in RNA binding, while the C-terminal domain is larger and contains the catalytic machinery. Both proteins also exhibit flexibility of one domain relative to the other.

During tracing of the RlmB model from the experimental electron density map, it was noticed that the polypeptide chain threaded through itself, forming a knot. A knot in a protein structure occurs if a knot would result in the chain when either end of the polypeptide chain was grasped and pulled apart. Deep knots, in which a long piece of polypeptide is threaded through itself, are exceedingly rare in protein structures and have been found in only one other protein structure previously, that of acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase (PDB 1YVE [64]). Concurrently, the structures of other methyltransferases belonging to the same family as RlmB have shown a similar knotted structure, indicating that this is a defining structural feature for this family of enzymes (45). The functional significance of the knot is that it both forms part of the active-site region and is involved in dimer formation.

CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM

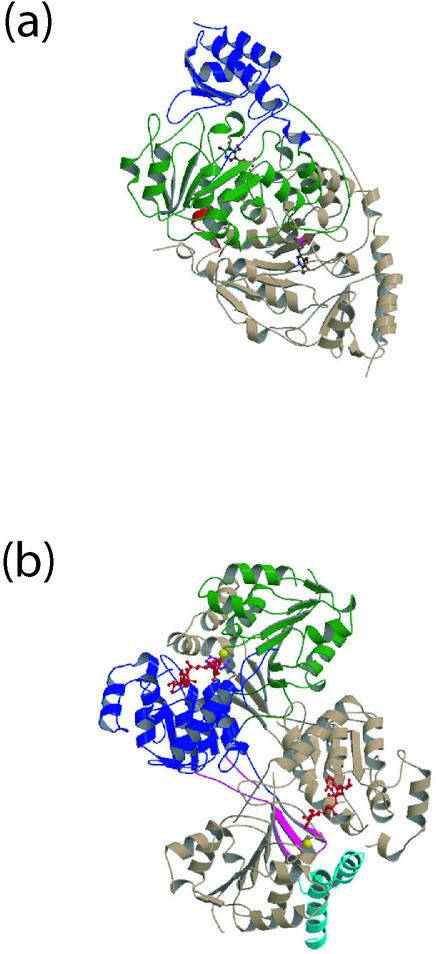

RffH. l-Rhamnose is a critical component of the O antigen of lipopolysaccharide found in bacteria (56). Two sets of genes contribute to synthesis of O antigen, those of the rfb and rff clusters (38). In E. coli, two paralogous genes, RfbA (of the rfb cluster) and RffH (of the rff cluster), function as glucose-1-phosphate thymidyltransferases (EC 2.7.7.24). These enzymes catalyze the first step in the synthesis of l-rhamnose from glucose-1-phosphate and dTTP (56). The enzymes RfbA and RffH from E. coli have ≈65% sequence identity. As these enzymes are not found in mammals and the O antigen is a well-documented virulence determinant in pathogenic bacteria, RffH is an attractive antimicrobial target.

Several structures of RmlA and RfbA, some with bound ligands, were determined previous to the structure determination of E. coli RffH (5, 7, 78). While it would appear at first glance that an additional structure would not contribute much in the way of new information, the structure of E. coli RffH unexpectedly revealed new information about the role of Mg2+ in catalysis for this group of enzymes (59). Comparison of the RffH complex with that of other nucleoside triphosphate transferases and their complexes with substrates and products allowed us to formulate a hypothesis on the dynamics of the events occurring during the reaction and the role of the Mg2+ ion in stabilization of the phosphosugar substrate and correct positioning of its phosphate for attack on the α-phosphate of the nucleoside triphosphate (59).

RpiA. Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase (RpiA; EC 5.3.1.6) catalyzes the interconversion of ribose-5-phosphate and ribulose-5-phosphate, a key reaction in the nonoxidative branch of the pentose phosphate cycle. In so doing, it contributes intermediates to the formation of nucleic acids (via ribose-5-phosphate) or to glycolysis (via glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate). RpiA is one of two ribose-5-phosphate isomerases in E. coli, the other being RpiB (61). RpiA is constitutively expressed and accounts for the majority of active enzyme in E. coli, while RpiB is inducible. These two proteins have been found to be unrelated in sequence.

The crystal structure of E. coli RpiA revealed a dimeric enzyme, with each monomer consisting of two domains with a shallow cleft between them (Fig. 4b) (49). Dimer formation occurs through interaction of the small domain of each monomer. The larger domain shows structural resemblance to other sugar or sugar-phosphate binding proteins, including glutaconate coenzyme A transferase, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase and d-ribose binding protein. This domain also appears to be the location of the active site, containing the conserved residues Asp81, Asp84, and Lys94. A more detailed structural analysis of E. coli RpiA in the presence of the inhibitor arabinose-5-phosphate helped define the catalytic mechanism for this enzyme (77). Asp81 appears to play a role in opening of the sugar ring, while Glu103 is proposed to be the general base. Lys94 and Glu-84 may assist in stabilizing the intermediate and transition states of the reaction, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Structure of carbohydrate-processing enzymes from E. coli. (a) Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase RpiA dimer (PDB code 1LKZ), with the small domain (green) and large domain (blue) shown. The structure revealed a dimeric enzyme, with each monomer having two domains (49). The putative active-site residues Asp81, Asp84, and Lys94 cluster near the active-site cleft. (b) Glucose-1-phosphate thymidyltransferase RffH dimer (PDB code 1MC3). dTTP (red) and Mg2+ (sky blue) are depicted in ball-and-stick representation. The RffH structure adopts a dimer-of-dimers arrangement (59). The Mg2+ ion within the active site serves to correctly orient the substrate molecules, thereby facilitating an SN2 nucleophilic attack at the dTTP α-phosphate.

CONCLUSIONS

The few examples described herein show the value of a broad-based approach to structure determination with the view to exploitation of a relatively simple model organism. The relative simplicity of cloning and expression of bacterial genes in a homologous expression system provides an opportunity to concentrate on subsequent steps in the structure determination pipeline, in particular protein purification and crystallization. Progress in these steps will have an impact not only on the throughput of the structural genomics projects but also on the ongoing work in many other structural biology laboratories that concentrate on focused problems. The biological insight gained through structural investigation of E. coli proteins, one of the most important model systems in contemporary biology, will not only benefit the microbiological community but will have a profound effect on understanding the living cell and, eventually, on the development of new antimicrobial agents.

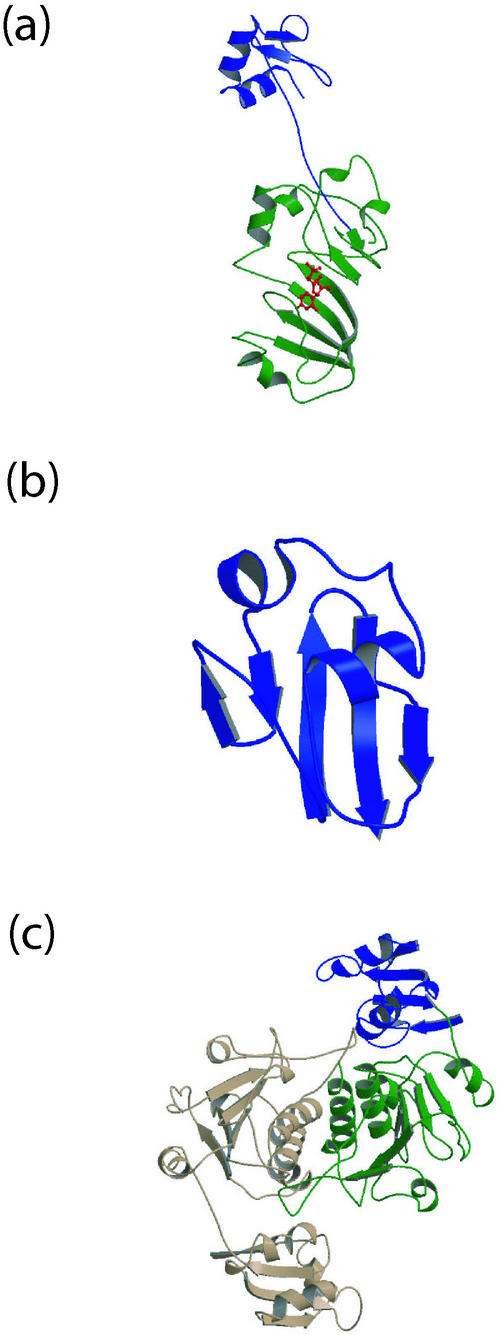

HisC. The crystal structure of l-histidinol phosphate aminotransferase (HisC; EC 2.6.1.9) catalyzes the seventh step in histidine biosynthesis, the pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent conversion of 3-(imidazol-4-yl)-2-oxopropyl phosphate and glutamate to 2-oxoglutarate and histidinol phosphate (24). Three crystal structures were determined, that for the pyridoxamine-5′-phosphate (PMP) form of HisC, the internal aldimine form bound to PLP, and in covalent complex with PLP and l-histidinol phosphate (57).

Each monomer of HisC consists of two domains, a larger, 218-residue PLP-binding domain, and a smaller domain of about 115 amino acids (Fig. 2a). As well, a 16-residue N-terminal arm contributes to dimerization of the enzyme. The structure of the PLP-binding domain has an α/β/α architecture and resembles that of other PLP-binding aminotransferases, including those of the aspartate and tyrosine aminotransferases. This structural similarity is further reflected by sequence similarity, with the PLP-binding domain from HisC showing 24% and 21% sequence identity to the corresponding domains from aspartate and tyrosine aminotransferases, respectively. Analysis of interactions between PLP and HisC showed that several residues, including Tyr55, Asn157, Asp184, Tyr187, Ser213, Lys214, and Arg222, are conserved in the sequences of aspartate, tyrosine, and histidinol phosphate aminotransferases. Together, these results are consistent with a common evolutionary origin for this group (family I) of aminotransferases (26, 40).

FIG. 2.

Structures of enzymes from the histidine biosynthesis pathway of E. coli. (a) l-Histidinol phosphate aminotransferase (HisC) dimer as bound to PMP (PDB code 1FG7). The small domain (blue) and large domain (green) containing bound pyridoxamine-5′-phosphate (PMP, red) are depicted. This enzyme catalyzes the seventh step in the histidine biosynthesis pathway. Structures were determined with bound PMP and PLP as well as with both l-histidinol phosphate and PLP, the latter structure resembling a gem-diamine intermediate (57). (b) l-Histidinol dehydrogenase dimer bound to Zn2+, l-histidinol, and NAD (PDB code 1KAE). The two larger domains, 1 (blue) and 2 (green), contain a Rossmann fold, with domain 3 (magenta) containing a three-stranded β-sheet and 4 (sky blue) a two-helix hairpin. The ligands Zn2+ (yellow) and NAD/l-histidinol (red) are depicted in ball-and-stick representation. The HisD structure and its complexes revealed the role of Zn2+ in substrate binding, a gene duplication event leading to two incomplete Rossmann fold domains, and the roles of His327 and Glu326 in catalysis (4). These and subsequent figures were prepared with the program Molscript (18) and rendered with Raster3D (39).

A surprising result was obtained when crystals of HisC were soaked in l-histidinol phosphate. Rather than observing the expected external aldimine, we observed a covalent, tetrahedral complex between HisC(Lys214NZ), l-histidinol phosphate, and PLP (57). In structural terms, this tetrahedral complex resembled the gem-diamine intermediate that is predicted to form during conversion of the internal to external aldimine (29). This intermediate had previously been detected spectroscopically and its structure inferred from modeling, but its structure had not been determined crystallographically. The observation of this complex in HisC crystals may be a consequence of protein-packing interactions in the crystal state that prevent its conversion to the external aldimine.

HisD. The last step of l-histidine biosynthesis, the four-electron oxidation of l-histidinol to l-histidine, is performed by l-histidinol dehydrogenase (HisD; EC 1.1.1.23). This enzyme catalyzes the formation of l-histidine in two steps; NAD-dependent oxidation of l-histidinol to l-histindaldehyde, followed by another NAD-dependent oxidation to form l-histidine. It has been shown previously that HisD is a Zn-metalloenzyme (19), with the Zn atom essential for activity.

Like HisI and HisC, HisD is a dimeric enzyme. Each HisD monomer consists of four domains, two larger (1 and 2) and two smaller (3 and 4). The two larger domains adopt incomplete Rossmann folds and contain the binding sites for NAD (domain 1) and l-histidinol/Zn2+ (domain 2), respectively (Fig. 2b). While these domains are structurally conserved, they have insignificant sequence similarity, suggesting that they arose by an ancestral gene duplication event, followed by divergence in function to bind either NAD or l-histidinol/Zn2+. As expected, these domains show structural similarity with other Rossmann fold-containing enzymes, although they represent a new sequence family for such proteins. Overall, the four domains of HisD together represent a novel tertiary fold (4).

The Zn2+ ion present at the HisD active site is bound in an octahedral coordination environment, with four ligands from the protein (Gln259, His262, Asp360, and His419) and two from l-histidinol (ND1 and N). While mutagenesis experiments correctly predicted His262 and His419 as ligands (43), the involvement of the l-histidinol amino group in Zn2+ coordination was not predicted (28). Unlike previous studies that suggested that Zn2+ participates directly in catalysis (28, 66), the structure of enzyme-ligand complexes indicated that Zn2+ is involved in substrate binding through proper positioning of l-histidinol within the active site.

Acknowledgments

We thank the various members of the project for their contributions to the structures described here: M. Adams, J. Barbosa, L. Boju, S. Gandhi, W. Huang, P. Iannuzzi, J. Jia, G. Kozlov, R. Larocque, Y. Li, C. Lievre, V. Lunin, G. Michel, F. Ouellet, G. Pal, E. Rangarajan, S. Raymond, V. Sauvé, A. Schmidt, J. Schrag, C. Smith, M. Suits C. Udell, J. Zheng, and L. Volpon. We also thank N. O'Toole for statistics relating to E. coli proteins being worked as part of other structural genomics projects and A. Tocilj for assistance with figures.

This research is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant 200103GSP-90094-GMX-CFAA-19924 to M.C., K.G., I.K., and Z.J.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alifano, P., R. Fani, P. Lio, A. Lazcano, M. Bazzicalupo, M. S. Carlomagno, and C. B. Bruni. 1996. Histidine biosynthetic pathway and genes: structure, regulation and evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 60:44-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin,1999. Novel predicted RNA-binding domains associated with the translation machinery. J. Mol. Evol. 48:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banfield, M. J., J. S. Lott, V. L. Arcus, A. A. McCarthy, and E. N. Baker. 2001. Structure of HisF, a histidine biosynthetic protein from Pyrobaculum aerophilum. Acta Crystallogr. D57:1518-1525. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Barbosa, J. A. R. G., J. Sivaraman, Y. Li, R. Larocque, Matte, A., Schrag, J. D., and Cygler, M. 2002. Mechanism of action and NAD+ binding mode revealed by the crystal structure of l-histidinol dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1859-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton, W. A., J. Lesniak, J. B. Biggins, P. D. Jeffrey, J. Jiang, K. R. Rajashankar, J. S. Thorson, and D. B. Nikolov. 2001. Structure, mechanism and engineering of a nucleotidyltransferase as a first step toward glycorandomization. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman, H. M., J. Westbrook, Z. Feng, G. Gilliland, T. N. Bhat, H. Weissig, I. N. Shindyalov, and P. E. Bourne. 2000. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:235-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blankenfeldt, W., M. Asuncion, J. S. Lam, and J. H. Naismith. 2000. The structural basis of the catalytic mechanism and regulation of glucose-1-phosphate thymidyltransferase (RlmA). EMBO J. 19:6652-6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, T. A. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and J. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady, D. R., and L. L. Houston. 1973. Some properties of the catalytic sites of imidazoleglycerol phosphate dehydratase-histidinol phosphate phosphatase, a bifunctional enzyme from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 248:2588-2592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner, S. E. 1999. Errors in genome annotation. Trends Genet. 15:132-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlomagno, M. S., L. Chiariotti, P. Alifano, A. G. Nappo, and C. B. Bruni,1988. Structure and function of the Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli K-12 histidine operons. J. Mol. Biol. 203:585-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhuri, B. N., S. C. Lange, R. S. Myers, S. V. Chittur, V. J. Davisson, and J. L. Smith. 2001. Crystal structure of imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase: a tunnel through a (β/α)8 barrel joins two active sites. Structure 9:987-997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conrad, J., L. Niu, K. Rudd, B. Lane, and J. Ofengand. 1999. 16S ribosomal RNA pseudouridine synthase RsuA of Escherichia coli: Deletion, mutation of the conserved Asp102 residue, and sequence comparison among all other pseudouridine synthases. RNA 5:751-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Ordine, R. L., T. J. Klein, and V. J. Davisson. 1999. N1-(5′-phosphoribosyl)adenosine-5′-monophosphate cyclohydrolase: purification and characterization of a unique metalloenzyme. Biochemistry 38:1537-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Decatur, W. A., and M. J. Fournier. 2002. rRNA modification and ribosome function. Trends Biochem. Sci 27:344-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Campo, M., Y. Kaya, and J. Ofengand. 2001. Identification and site of action of the reamining four putative pseudouridine synthases in Escherichia coli. RNA 7:1603-1615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douangamath, A., M. Walker, S. Beismann Driemeyer, M. C. Fernandez, R. Sterner, and M. Wilmanns. 2002. Structural evidence for ammonia tunneling across the (β/α)8 barrel of the imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase bienzyme complex. Structure 10:185-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esnouf, R. M. 1997. An extensively modified version of MolScript that includes greatly enhanced coloring capabilities. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 15:132-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Foster, P. G., L. Huang, D. V. Santi, and R. M. Stroud. 2000. The structural basis for tRNA recognition and pseudouridine formation by pseudouridine synthase I. Nat, Struct. Biol. 7:23-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grubmeyer, C., M. Skiadopoulos, and A. E. Senior. 1989. l-Histidinol dehydrogenase, a Zn2+-metalloenzyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 272:311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu, X., Y. Liu, and D. V. Santi. 1999. The mechanism of pseudouridine synthase I as deduced from its interaction with 5-fluouracil-tRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14270-14275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haruyama, K., T. Nakai, I. Miyahara, K. Hirotsu, H. Mizuguchi, H. Hayashi, and H. Kagamiyama. 2001. Structures of Escherichia coli histidinol-phosphate aminotransferase and its complexes with histidinol-phosphate and N-(5′-phosphopyridoxyl)-l-glutamate: double substrate recognition of the enzyme. Biochemistry 40:4633-4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi, T., K. Makino, M. Ohnishi, K. Kurokawa, K. Ishii, K. Yokoyama, C. G. Han, E. Ohtsubo, K. Nakayama, T. Murata, M. Tanaka, T. Tobe, T. Iida, H. Takami, T. Honda, C. Sasakawa, N. Ogasawara, T. Yasunaga, S. Kuhara, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, and H. Shinagawa. 2001. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 8:11-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoang, C., and X. Ferre-D'Amare. 2001. Cocrystal structure of a tRNA ψ55 pseudouridine synthase: Nucleotide flipping by an RNA-modifying enzyme. Cell 107:929-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu, L. C., M. Okamoto, and E. E. Snell. 1989. l-Histidinol phosphate aminotransferase from Salmonella typhimurium. Kinetic behavior and sequence at the pyridoxal-P binding site. Biochimie 71:477-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, L., M. Pookanjanatavip, X. Gu, and D. V. Santi. 1998. A conserved asparate of tRNA pseudouridine synthase is essential for activity and a probable nucleophilic catalyst. Biochemistry 37:344-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen, R. A., and W. Gu. 1996. Evolutionary recruitment of biochemically specialized subdivisions of family I within the protein superfamily of aminotransferases. J. Bacteriol. 178:2161-2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia, J., V. V. Lunin, V. Sauve, L.-W. Huang, A. Matte, and M. Cygler. 2002. Crystal structure of the YciO protein from Escherichia coli. Proteins 49:139-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanaori, K., N. Uodome, A. Nagai, D. Ohta, A. Ogawa, G. Iwasaki, and A. Y. Nosaka. 1996. 113Cd nuclear magnetic resonance studies of cabbage histidinol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 35:5949-5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirsch, J. F., G. Eichele, G. C. Ford, M. G. Vincent, J. N. Jansonius, H. Gehring, and P. Christen. 1984. Mechanism of action of aspartate aminotransferase proposed on the basis of its spatial structure. J. Mol. Biol. 174:497-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein, T. J., and V. J. Davisson. 1993. Imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase: the glutamine amidotransferase in histidine biosynthesis. Biochemistry 32:5177-5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koonin, E. V., Y. I. Wolf, and G. P. Karev. 2002. The structure of the protein universe and genome evolution. Nature 420:218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lang, D., R. Thoma, M. Henn-Sax, R. Sterner, and M. Wilmanns. 2000. Structural evidence for evolution of the α/β barrel scaffold by gene duplication. Science 289:1546-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesley, S. A., P. Kuhn, A. Godzik, A. M. Deacon, I. Mathews, A. Kreusch, G. Spraggon, H. E. Klock, D. McMullan, T. Shin, J. Vincent, A. Robb, L. S. Brinen, M. D. Miller, T. M. McPhillips, M. A. Miller, D. Scheibe, J. M. Canaves, C. Guda, L. Jaroszewski, T. L. Selby, M.-A. Elslinger, S. S. Taylor, K. O. Hodgson, I. A. Wilson, P. G. Schultz, and R. A. Stevens. 2002. Structural genomics of the Thermotoga maritime proteome implemented in a high-throughput structure determination pipeline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11664-11669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang, P., B. Labedan, and M. Riley. 2002. Physiological genomics of Escherichia coli protein families. Physiol. Genomics 9:15-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Link, A. J., K. Robison, and G. M. Church. 1997. Comparing the predicted and observed properties of proteins encoded in the genome of Escherichia coli K-12. Electrophoresis. 18:1259-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lohkamp, B., J. R. Coggins, and A. J. Lapthorn. 2000. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of ATP-phosphoribosyltransferase from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr. D56:1488-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovgren, J. M., and P. M. Wikstrom. 2001. The rlmB gene is essential for formation of Gm2251 in 23S rRNA but not for ribosome maturation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:6957-6960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marolda, C., and M. A. Valvano. 1995. Genetic analysis of the dTDP-rhamnose biosynthesis region of the Escherichia coli VW187 (O7:K1) rfb gene cluster: Identification of functional homologs of rfbB and rfbA in the rff cluster and correct location of the rffE gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:5539-5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merrit, E. A., and D. J. Bacon. 1997. Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277:505-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metha, P. K., T. I. Hale, and P. Christen. 1989. Evolutionary relationships among aminotransferases: tyrosine aminotransferase, histidinol-phosphate aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase are homologous proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 186:249-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michel, G., V. Sauve, R. Larocque, Y. Li, A. Matte, and M. Cygler. 2002. The structure of the RlmB 23S rRNA methyltransferase reveals a new methyltransferase fold with a unique knot. Structure 10:1303-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41a.Michel, G., A. W. Roszak, V. J. Sauvé, J. Maclean, A. Matte, J. R. Coggins, M. Cygler, and A. J. Lapthorn.2003. Structures of shikimate dehydrogenase AroE and its paralog YdiB. A common structural framework for different activities. J. Biol. Chem. 278:19463-19472. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Mueller, E. G. 2002. Chips off the old block. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:320-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagai, A., and D. Ohta. 1994. Histidinol dehydrogenase loses its catalytic function through the mutation of His261→Asn due to its inability to ligate the essential Zn. J. Biochem. 115:22-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nahum, L. A., and M. Riley. 2001. Divergence of function in sequence-related groups of Escherichia coli proteins. Genome Res. 11:1375-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nureki, O., M. Shirouzu, K. Hashimoto, R. Ishitani, T. Terada, M. Tamakoshi, T. Oshima, M. Chijimatsu, K. Takio, D. G. Vassylyev, T. Shibata, Y. Inoue, S. Kuramitsu, and S. Yokoyama. 2002. An enzyme with a deep trefoil knot for the active site architecture. Acta Crystallogr. D58:1129-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omi, R., H. Mizuguchi, M. Goto, I. Miyahara, H. Hayashi, H. Kagamiyama, and K. Hirotsu. 2002. Structure of imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase from Thermus thermophilus HB8: Open-closed conformational change and ammonia tunneling. J. Biochem. 132:759-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Toole, N., J. A. Barbosa, O. G., Y. Li, L.-W. Huang, A. Matte, and M. Cygler. 2003. Crystal structure of a trimeric form of dephosphocoenzyme A kinase from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 12:327-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett 3rd, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Greor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Balttner. 2001. Genome sequence of the enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rangarajan, E. S., J. Sivaraman, A. Matte, and M. Cygler. 2002. Crystal structure of D-ribose-5-phosphate isomerase (RpiA) from Escherichia coli. Protein Struct. Funct. Genet. 48:737-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riley, M. 1998. Genes and proteins of Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rost, B. 1997. Protein structures sustain evolutionary drift. Fold. Des. 2:519-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmidt, A., J. Sivaraman, Y. Li, R. Larocque, J. A. Barbosa, C. Smith, A. Matte, J. D. Schrag, and M. Cygler. 2001. Three-dimensional structure of 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A ligase from Escherichia coli complexed with a PLP-substrate intermediate: inferred reaction mechanism. Biochemistry 40:5151-5160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schrag, J. D., W. Huang, J. Sivaraman, C. Smith, J. Plamondon, R. Larocque, A. Matte, and M. Cygler. 2001. The crystal structure of Escherichia coli MoeA, a protein from the molybdopterin synthesis pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 310:419-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Selinger, D. W., K. J. Cheung, R. Mei, E. M. Johansson, C. S. Richmond, F. R. Blattner, D. J. Lockhart, and G. M. Church. 2000. RNA expression analysis with a 30 base pair resolution Escherichia coli genome array. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:1262-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serres, M. H., S. Gopal, L. A. Nahum, P. Liang, T. Gaasterland, and M. Riley. 2001. A functional update of the Escherichia coli K-12 genome. Genome Biol. 2:research0035.1-0035.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shibaev, V. 1986. Biosynthesis of bacterial polysaccharide chains composed of repeating units. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 44:277-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sivaraman, J., Y. Li, R. Larocque, J. D. Schrag, M. Cygler, and A. Matte. 2001. Crystal structure of histidinol phosphate aminotransferase (HisC) from Escherichia coli, and its covalent complex with pyridoxal-5′-phosphate and l-histidinol phosphate. J. Mol. Biol. 311:761-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sivaraman, J., V. Sauvé, R. Larocque, E. A. Stura, J. D. Schrag, M. Cygler, and A. Matte. 2002. Structure of the 16S rRNA pseudouridine synthase RsuA bound to uracil and UMP. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sivaraman, J., V. Sauvé, A. Matte, and M. Cygler. 2002. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli glucose-1-phosphate thymidyltransferase (RffH) complexed with dTTP and Mg2+. J. Biol. Chem. 277:44214-44219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith, J. E., B. S. Cooperman, and P. Mitchell. 1992. Methylation sites in Escherichia coli ribosomal RNA: localization and identification of four new sites of methylation in 23S rRNA. Biochemistry 31:10825-10834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sorensen, K. I., and Hove- B. Jensen. 1996. Ribose catabolism of Escherichia coli: characterization of the rpiB gene encoding ribose phosphate isomerase B and of the rpiR gene, which is involved in regulation of rpiB expression. J. Bacteriol. 178:1003-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Staker, B. L., P. Korber, J. C. A. Bardwell, and M. A. Saper. 2000. Structure of Hsp15 reveals a novel RNA-binding motif. EMBO J. 19:749-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tao, H., C. Bausch, C. Richmond, F. R. Blattner, and T. Conway. 1999. Functional genomics: Expression analysis of Escherichia coli growing on minimal and rich media. J. Bacteriol. 181:6425-6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor, W. R. 2000. A deeply knotted protein structure and how it might fold. Nature 406:916-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teichmann, S. A., S. C. G. Rison, J. M. Thornton, M. Riley, J. Gough, and C. Chothia. 2001. The evolution and structural anatomy of the small molecule metabolic pathways in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 311:693-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Teng, H., and C. Grubmeyer. 1999. Mutagenesis of histidinol dehydrogenase reveals roles for conserved histidine residues. Biochemistry 38:7363-7371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tjaden, B., R. M. Saxena, S. Stolyar, D. R. Haynor, E. Kolker, and C. Rosenow. 2002. Transcriptome analysis of Escherichia coli with high-density oligonucleotide probe arrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3732-3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomita, M. 2001. Whole-cell simulation: a grand challenge of the 21st century. Trends Biotechnol. 19:205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tonella, L., C. Hoogland, P.-A. Binz, D. F. Hochstrasser, and J.-C Sanchez. 2001. New perspectives in the Escherichai coli proteome investigation. Proteomics 1:409-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69a.Volpon, L., C. Lievre, M. J. Osborne, S. Gandi, P. Iannuzzi, R. Larocque, M. Cygler, K. Gehring, and I. Ekiel. 2003. The solution structure of YbcJ from Escherichia coli reveals a recently discovered αL motif involved in RNA binding. J. Bacteriol. 185:4204-4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Welch, R. A., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, P. Redford, P. Roesch, D. Rasko, E. L. Buckles, S.-R. Liou, A. Boutin, J. Hackett, D. Stroud, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, N. T. Perna, H. L. T. Mobley, M. S. Donnenberg, and F. R. Blattner. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17020-17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Winkler, M. E. 1996. Biosynthesis of histidine, p. 485-505. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 72.Wojcik, J., I. G. Boneca, and P. Legrain. 2002. Prediction, assessment and validation of protein interaction maps in bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 323:763-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wrzesinski, J., A. Bakin, K. Nurse, B. G. Lane, and J. Ofengand. 1995. Purification, cloning and properties of the 16S pseudouridine 516 synthase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 34:8904-8913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yamaguchi, A., M. Iwadate, E. Suzuki, K. Yura, S. Kawakita, H. Umeyama, and M. Go. 2003. Enlarged FAMSBASE: protein 3D structure models of genome sequences for 41 species. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:463-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zarebinski, T. I., L.-W. Hung, H.-J. Dieckmann, K.-K. Kim, H. Yokota, R. Kim, and S.-H. Kim. 1998. Structure based assignment of the biochemical function of a hypothetical protein: A test case of structural genomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15189-15193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang, H., K. Huang, Z. Li, L. Banerjei, K. E. Fisher, N. V. Grishin, E. Eisenstein, and O. Herzberg. 2000. Crystal structure of YbaK protein from Haemophilus influenzae (HI1434) at 1.8 Å resolution: functional implications. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 40:86-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang, R., C. E. Andersson, A. Savchenko, T. Skarina, E. Evdokimova, S. Beasley, C. H. Arrowsmith, A. M. Edwards, A. Joachimiak, and S. L. Mowbray. 2003. Structure of Escherichia coli ribose-5-phosphate isomerase. A ubiquitous enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway and the calvin cycle. Structure 11:31-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zuccotti, S., D. Zanardi, C. Rosano, L. Sturia, M. Tonetti, and M. Bolognesi. 2001. Kinetic and crystallographic analyses support a sequential-orderd bi-bi catalytic mechanism for Escherichia coli glucose-1-phosphate thymidyltransferase. J. Mol. Biol. 313:831-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]