Abstract

Objective:

To examine age-related differences in pain, catastrophizing, and affective distress (depression and anxiety) after athletic injury and knee surgery.

Design and Setting:

Participants were assessed with measures of pain intensity, pain-related catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety symptoms at 24 hours after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery.

Subjects:

Twenty patients (10 adolescents, 10 adults) with an acute complete tear of the ACL.

Measurements:

Pain was assessed by Visual Analog Scale (VAS), catastrophizing with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), depressive symptoms with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and anxiety with the state form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S).

Results:

At 24 hours postsurgery, adolescents reported greater pain, catastrophizing, and anxiety than adults. Ancillary analyses showed that helplessness and rumination were significant contributors to the differences in catastrophizing. Further, an analysis of covariance showed that controlling for the effects of catastrophizing, the adolescent and adult differences in pain scores were reduced to a null effect.

Conclusions:

After ACL surgery, athletic adolescents and adults differed significantly in pain, catastrophizing, and anxiety. Catastrophizing seemed to be a particularly strong factor in postoperative pain differences between adolescents and adults, with clinical-management implications. These data indicate the need for continued research into specific pain- and age-related factors during the acute postoperative period for athletes undergoing ACL surgery.

Keywords: catastrophizing, knee surgery

As many as 20 million children and adolescents participate in organized sport programs in the United States alone,1 and more than $8 million was spent on childhood sport injuries in 1987.2 In addition to the monetary costs, sport injuries are important because an athlete's physical and psychological well-being are threatened.3 Issues of adjustment and pain after sport injury are salient for adolescents because of incomplete development in both the physical and emotional realms4 and the fact that pain is the most pervasive and debilitating obstacle to effective rehabilitation of sport-related injury.5,6 We also recognize that research on pain after sport injury is limited, and adolescents have received little attention as a group.

Most sport injuries for 8- to 17-year-olds involve lower extremities (73%), with a significant proportion occurring in the knee (22%).7 Injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are prevalent and debilitating knee injuries.8–10 With current research suggesting that catastrophizing (ie, an exaggerated negative mental set brought to bear during actual or anticipated painful experience) about pain is a significant predictor of pain intensity in athletes,11 and given that no published reports have examined postoperative pain for adolescents after ACL surgery, we examined acute postoperative pain, catastrophizing, and affective distress (depression and anxiety) after ACL surgery across adolescents and adults.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty recreational athletes participated in this study. All were scheduled for arthroscopic ACL reconstructive surgery using the patellar-tendon autograft procedure and were recruited from the orthopaedic surgery service of the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Of the 10 adolescent patients (range, 16–18 years of age), 5 were female and 6 had a noncontact injury, with all reporting significant desire to return to their sport. Of the 10 adult patients (range, 20–53 years), 4 were female and 8 had a noncontact injury, with all reporting significant desire to return to their sport.

Measures

Demographic and Injury-Related Variables

We obtained demographic and specific data regarding the injury through a questionnaire inquiring about age, sex, type of injury, and the desire to return to preinjury sport. All athletes were undergoing their primary ACL surgery, and no bilateral surgeries were performed. No athletes reported a history of chronic knee pain or chronic knee injury before the ACL injury.

Pain

Pain intensity was assessed with 2 separate Visual Analog Scale (VAS) measures. Patients were asked to rate their pain intensity while resting and while moving. The VAS consisted of a 10-cm horizontal line with 2 endpoints, or anchors, labeled “no pain” (0) and “worst pain ever” (10). The VAS pain measures provide a simple and efficient measure of pain intensity, widely used in both clinical and experimental pain research, offering a quick assessment of pain, sensitivity to both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions to reduce pain,12 and high association with pain measured on verbal and numeric pain-rating scales.13 The major advantage of VAS measures of pain intensity is their ratio scale properties,14 which imply equality of ratios, thus allowing one to compare percentage differences between VAS assessments made over time.

Catastrophizing

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale15 (PCS) was used to assess catastrophizing. The PCS asks the respondents to reflect upon past painful experiences and to rate the degree to which they experienced each of the thoughts or feelings that are the items of the scale. Each item is rated in reference to being in pain on a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). Examples of items representing each of the 3 PCS subscales follow: rumination, “I can't seem to keep it out of my mind”; magnification, “I think of other painful experiences”; helplessness, “I feel I can't go on.” The PCS has demonstrated reliability and validity.15 Scores range from 0 to 52, with higher values representing greater catastrophizing.

Depressive Symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory16 (BDI) was used to assess depressive symptoms. The BDI has been used as a measure of depressive symptoms in several medical populations, including chronic pain patients and surgical patients.17 The BDI is both reliable16,18 and valid19 and is a standard measure of depression in medical and psychosocial research.

Anxiety

The state form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory20 (STAI-S) was used to assess situation-specific anxiety. The STAI is a 40-item self-report questionnaire that measures state and trait anxiety. The STAI has high internal consistency and validity20 and has been successfully used in surgical populations.21 Total scores are obtained by summing the values assigned to each response and range from a minimum of 20 to a maximum of 80, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms.

Procedure

During initial contact, we provided potential participants with general information about the nature of the study; those interested were screened according to eligibility requirements (ie, scheduled for arthroscopically assisted ACL patellar-tendon autograft; injury incurred through sport; no history of chronic pain, current dementia, or acute psychopathology; no history of neurologic disease). We informed participants that if a significant postoperative complication developed after surgery (eg, additional corrective surgery was needed), their data might be excluded. We collected data 24 hours postoperatively at 10 AM after ACL surgery in the hospital. Patients completed the VAS, PCS, BDI, and STAI-S. There were no cases of significant postoperative complications. An institutional ethics review board approved the study, and we obtained written informed consent from participants before data collection.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics and t tests were used to examine the associations and differences in the dependent measures between the adolescent and adult groups for the 24-hour postoperative assessment. The t tests were conservatively corrected for multiple test error.22 A one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to examine the particular contribution of catastrophizing to pain reports.

RESULTS

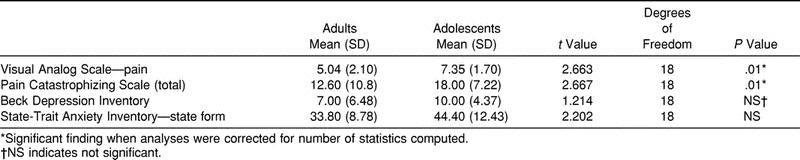

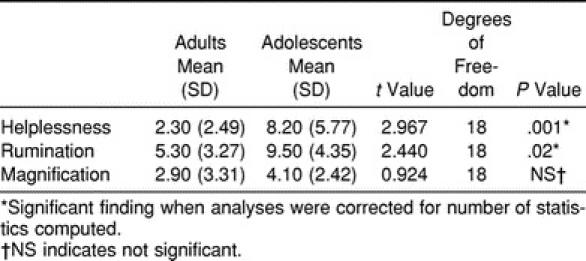

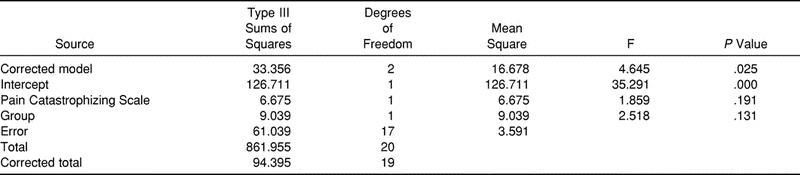

Reports of 24-hour pain while moving and resting were highly correlated (r = 0.80, P < .01) and were therefore collapsed to form a single pain index.22 The differences across the adolescent and adult groups at the 24-hour postoperative assessment are presented in Table 1. Although there were no significant differences for depressive symptoms, the adolescent sample reported greater pain intensity (t18 = 2.66, P < .01) and catastrophizing (t18 = 2.67, P < .01) when compared with adults. Ancillary analyses were conducted for the subscales of the PCS (Table 2). Adolescents reported greater catastrophic helplessness (t18 = 2.97, P < .001) and rumination-based catastrophic thought (t18 = 2.44, P < .02) with regard to their pain than did adults. An ANCOVA model produced a nonsignificant pain-score difference between groups after controlling for the variance contributed by catastrophizing (F1,19 = 2.52, P > .05) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Measures of Pain, Catastrophizing, Depression, and Anxiety in Adults and Adolescents 24 h After Surgery

Table 2.

Measures on the Subscales of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale in Adults and Adolescents 24 h After Surgery

Table 3.

Analysis of Covariance Model Examining Tests of Between-Subjects Effects (Adolescents and Adults) for Pain at 24 h Postoperative, Controlling for Catastrophizing (Pain Catastrophizing Scale)

DISCUSSION

Pain and catastrophizing were greater in adolescents at 24 hours postsurgery. Further, catastrophizing may have mediating effects on the observed pain-score differences between the adolescent and adult samples because controlling for catastrophizing eliminated the group difference for pain. Catastrophizing is a significant factor in the postoperative period in other adolescent samples,23 and these data are the first to indicate that catastrophizing is significant in athletic adolescents after ACL procedures, with adolescents reporting greater pain-related helplessness and rumination than adults. Perhaps these data support previous suggestions that hospital patients may experience increased fear or helplessness because of the regimented, technologic system with little opportunity to exercise self-control behaviors.24 Thus, greater catastrophizing in adolescents may be influenced by their relative lack of understanding about the nature of their injury, their lack of experience with recovery from injury, and the potential threat to the loss of competitive status.

Catastrophizing is associated with pain15 in many reports, and catastrophic helplessness has been suggested to function as a secondary appraisal of one's confidence in the ability to manage pain.15,25 Cognitive appraisal models have shown that negative thinking may hinder rehabilitation through increased emotional disturbance,26 lending support to the notion that controlling catastrophizing in the athlete may act to decrease negative outcomes. Speculation as to how catastrophizing may affect pain suggests impairment in the ability to make effective use of particular coping strategies such as distraction.27 Possibly, the more uncertainty characterizes the situation for the adolescent, the greater the tendency to be catastrophic about the probability of negative outcomes. It is important to note that controlling for catastrophizing eliminates the significance of pain differences between the adolescents and adults, indicating that clinical postoperative pain management should target catastrophizing for intervention, especially in adolescents.

Catastrophizing may have implications beyond the acute ACL postoperative period, when the adolescent's responses to injury might play a significant role in the decision to continue involvement in sport. Ultimately, for high catastrophizers, the negative effect of heightened pain experience may lead to premature termination of involvement in sport. Although it is not direct evidence of termination in athletic sport, recent researchers have documented that catastrophizing is predictive of activity intolerance in sedentary undergraduate students after an exercise protocol designed to induce muscle soreness. In particular, under conditions in which movement is associated with pain, catastrophizing appears to contribute to a reduction in the maximal weight study participants were able or willing to lift.28 These data relate to previous findings in that individuals higher in catastrophizing will not avoid sporting activities when no pain is present,29 but catastrophizers are more likely to avoid activity when pain is present.28 Cognitive-based strategies reduce catastrophizing and acute pain and may be useful for athletes in acute pain management.11 Indeed, stress inoculation training procedures have been efficacious in decreasing postoperative pain, anxiety, and the number of days to return to physical functioning for athletes after arthroscopic meniscal-repair surgery.30

Although not significant after correcting for the number of analyses, elevated anxiety at the 24-hour postoperative assessment is also noteworthy. Previous data show that adolescent pain on the first and third postoperative days is influenced by the presence of anxiety and the patient's maturational stage, and anxiety is often correlated with catastrophizing in pain studies.15 Gillies et al31 suggested that surgery in adolescents should include more effective pain management by raising awareness of the importance of both the psychological state and the adjustment to adolescence. Our study did not involve patients less than 16 years of age, so maturational influences must await future research.

Several limitations of our study are present, including sample size. A larger sample would allow for increased flexibility in hypotheses to be addressed. Also, the acute postoperative period may not be reflective of the overall perioperative experience for adolescents and adults. Following initial reactions after surgery, adolescents may go on to do as well as adults. In collecting prospective data after ACL surgery, researchers would be able to document effects of catastrophizing, pain, and affective distress in adolescent and adult athletes into the recovery/rehabilitation period of ACL surgery. Also, causal relations among these variables are not supported by the present analyses. Finally, as with all research defined to a particular setting, these data may not be reflective of populations outside the geographic and ethnic populations in our sample. Although not the focus of this study, cultural influences on pain reports are well documented. However, they do not present any convincing direction because they vary by measurement modality used.32

Along with the other suggestions for future studies, examining pain coping in adolescent athletes is important because coping may mediate postoperative distress and catastrophizing. Franck et al33 suggested that adolescents may cope by attending to what is causing the pain, or they may try to distract themselves from it, with remaining in control being an important factor in adolescents. If the individual is an “attender” (ie, wants information before and after the procedure) or a “distractor” (ie, prefers not being told anything about the procedure, tries to distract himself or herself after the procedure), matching pain interventions to coping may be the most efficacious approach.34

REFERENCES

- 1.Brustad RJ. Youth in sport: psychological considerations. In: Singer RN, Murphey M, Tennant LK, editors. Handbook of Research in Sport Psychology. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1993. pp. 695–717. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landry GL. The Benefits of Sport Participation. Vol 2. Boston, MA: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Academy of Pediatrics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danish S. Psychological aspects in the case and treatment of athletic injuries. In: Vinger P, Hoerner E, editors. Sport Injuries: The Unthwarted Epidemic. Boston, MA: Year Book-Medical Publishers; 1986. pp. 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martens R. Psychological perspectives. In: Cahill BR, Pearl AJ, editors. Intensive Participation In Children's Sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1993. pp. 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heil J. Psychology of Sport Injury. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor J, Taylor S. Pain education and management in the rehabilitation from sports injury. Sport Psychol. 1998;12:68–88. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backx FJG, Erich WBM, Kemper AB, Verbeek AL. Sports injuries in school-aged children: an epidemiological study. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:234–240. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR. Fate of the ACL-injured patient: a prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:632–644. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noyes FR, Mooar PA, Matthews DS, Butler DL. The symptomatic anterior cruciate-deficient knee, part I: the long-term functional disability in athletically active individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:154–162. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198365020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roos H, Ornell M, Gardsell P, Lohmander LS, Lindstrand A. Soccer after anterior cruciate ligament injury—an incompatible combination? A national survey of incidence and risk factors and a 7-year follow-up of 310 players. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66:107–112. doi: 10.3109/17453679508995501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan MJL, Tripp DA, Rodgers WM, Stanish W. Catastrophizing and pain perception in sports participants. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2000;12:151–167. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belanger E, Melzack R, Lauzon P. Pain of first trimester abortion: a study of psychosocial and medical predictions. Pain. 1989;36:339–350. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekblom A, Hansson P. Pain intensity measurements in patients with acute pain receiving afferent stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:481–486. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price DD, Harkins SW. The combined use of experimental pain and visual analogue scales in providing standardized measurement of clinical pain. Clin J Pain. 1987;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croog SH, Baume RM, Nalbandian J. Pre-surgery psychological characteristics, pain response, and activities impairment in female patients with repeated periodontal surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00089-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT. Depression: Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bumberry W, Oliver JM, McClure JN. Validation of the Beck Depression Inventory in a university population using psychiatric estimate as the criterion. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:150–155. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults: Sampler Set, Manual, Test, Scoring Key. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson FV, Zimmerman L, Barnason S, Nieveen J, Schmaderer M. The relationship and influence of anxiety on postoperative pain in the coronary artery bypass graft patient. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15:102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett-Branson SM, Craig KD. Postoperative pain in children: developmental and family influences on spontaneous coping strategies. Can J Behav Sci. 1993;25:355–383. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoudemire A. Psychologic and emotional reactions to illness and surgery. In: Lubin MF, Walker HK, editors. Medical Management of the Surgical Patient. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daly JM, Brewer B, Van Raalte JL, Petitpas AJ, Sklar JH. Cognitive appraisal, emotional adjustment, and adherence to rehabilitation following knee surgery. J Sport Rehabil. 1995;4:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heyneman NE, Fremouw WJ, Gano D, Kirkland F, Heiden L. Individual differences and the effectiveness of different coping strategies for pain. Cog Ther Res. 1990;14:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallis TM. A complete component analysis of stress inoculation for pain tolerance. Cog Ther Res. 1984;8:313–329. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan MJ, Rodgers WM, Wilson PM, Bell GJ, Murray TC, Fraser SN. An experimental investigation of the relation between catastrophizing and activity intolerance. Pain. 2002;100:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross MJ, Berger RS. Effects of stress inoculation training on athletes' postsurgical pain and rehabilitation after orthopedic injury. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:406–410. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillies ML, Smith LN, Parry-Jones WL. Postoperative pain assessment and management in adolescents. Pain. 1999;79:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeResche L. Gender, cultural, and environmental aspects of pain. In: Loeser JD, Butler SH, Chapma CR, Turk DC, editors. Bonica's Management of Pain. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franck LS, Greenberg CS, Stevens B. Pain assessment in infants and children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2000;3:487–512. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fanurik D, Zeltzer LK, Roberts MC, Blount RL. The relationship between children's coping styles and psychological interventions for cold pressor pain. Pain. 1993;53:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]