Abstract

Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis produces parasporal insecticidal crystal proteins (ICPs) that have larvicidal activity against some members of the order Diptera, such as blackflies and mosquitoes. Hydrolysis of the ICPs in the larval gut results in four major proteins with a molecular mass of 27, 65, 128, and 135 kDa. Toxicity is caused by synergistic interaction between the 25-kDa protein (proteolytic product of the 27-kDa protein) and one or more of the higher-molecular-mass proteins. Equilibrium adsorption of the proteins on the clay minerals montmorillonite and kaolinite, which are homoionic to various cations, was rapid (<30 min for maximal adsorption), increased with protein concentration and then reached a plateau (68 to 96% of the proteins was adsorbed), was significantly lower on kaolinite than on montmorillonite, and was not significantly affected by the valence of the cation to which the clays were homoionic. Binding of the toxins decreased as the pH was increased from 6 to 11, and there was 35 to 66% more binding in phosphate buffer at pH 6 than in distilled water at pH 6 or 7.2. Only 2 to 12% of the adsorbed proteins was desorbed by two washes with water; additional washings desorbed no more toxins, indicating that they were tightly bound. Formation of clay-toxin complexes did not alter the structure of the proteins, as indicated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the equilibrium supernatants and desorption washes and by dot blot enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of the complexes, which was confirmed by enhanced chemiluminescence Western blot analysis. Free and clay-bound toxins resulted in 85 to 100% mortality of the mosquito Culex pipiens. Persistence of the bound toxins in nonsterile water after 45 days was significantly greater (mortality of 63% ± 12.7%) than that of the free toxins (mortality of 25% ± 12.5%).

Bacillus thuringiensis is a gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium that forms parasporal insecticidal crystal proteins (ICPs) during sporulation. The ICPs, composed of related δ-endotoxins that are classified into four major classes (Cry1, Cry2, Cry3, and Cry4), are produced by different subspecies of B. thuringiensis and exhibit specific insecticidal activities towards the larvae of members of the orders Lepidoptera, Diptera, and Coleoptera, as well as towards some other organisms. After ingestion, the ICPs are solubilized and hydrolyzed by the high pH (9 to 11) and specific proteases of the insect midgut. The hydrolytic products bind to receptors on the midgut epithelium and form pores, which results in osmotic lysis of the epithelial cells and is eventually fatal (1, 3, 6, 9, 14, 19). The ICPs of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis are specifically lethal to some members of the order Diptera, such as blackflies and mosquitoes. The hydrolysis of the parasporal body in the larval gut results in four major proteins with a molecular mass of 27, 65, 128, and 135 kDa. The 135-, 128-, and 65-kDa proteins are designated Cry4 proteins, and the 27-kDa protein is a cytolytic factor, CytA. Toxicity is caused by synergistic interaction between the 25-kDa protein (proteolytic product of the 27-kDa protein) and one or more of the proteins with a higher molecular mass (5, 13).

Surface-active particles (e.g., clays and humic substances), which have a net negative surface charge, are important in the persistence of many organic molecules in soil and other natural habitats, as they render the molecules resistant to biodegradation (20). Insecticidal proteins produced by subspecies of B. thuringiensis become resistant to biodegradation when bound to clays and humic acids, although they retain their insecticidal activity (21-24, 27). The accumulation of these toxins in the environment could pose a hazard to nontarget organisms (including beneficial insects), increase the selection of toxin-resistant target insects, and/or enhance the control of target insect pests. Purified Cry1Ab protein from B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki (antilepidopteran) added to soil retained insecticidal activity for 234 days, the longest time in that study (26). Cry1Ab protein released in root exudates and from biomass of transgenic B. thuringiensis corn (Zea mays L.) accumulated and retained insecticidal activity in soil for 180 days and 3 years, respectively, the longest times in those studies (16, 17).

Here we report the isolation, purification, and adsorption and binding of the insecticidal toxins from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis on homoionic clay minerals and the toxicity of the clay-toxin complexes to the mosquito Culex pipiens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis cultures.

Cultures of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis were isolated from Teknar Flowable Formulation (Abbott Laboratories). Cultures were maintained on nutrient agar at 4°C.

Purification of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxins.

Cultures of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis were grown in Erlenmeyer flasks containing 300 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Difco) with shaking (200 rpm) at 28°C until sporulation (usually 5 days). Cell lysis was induced by resuspension of centrifuged cells in 300 ml of double-distilled water (ddH2O) and shaking (200 rpm) for 2 days at 28°C. Aliquots of the suspension were layered onto gradients of Ludox HS-40 (Fisher Scientific Co.) (40 to 50% Ludox) and centrifuged in a swinging bucket rotor (Sorvall HB-4) at 12,000 × g for 1 h. The layer of crystals was removed, washed twice with ddH2O, and centrifuged at 26,300 × g to remove residual Ludox. The pellet was resuspended in ddH2O, lyophilized, and stored at −20°C (24, 25).

Solubilization of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxins.

Lyophilized toxins (100 mg) were added to 12.5 ml of 0.05 M NaOH and 12.5 ml of 10 mM EDTA, and the pH was adjusted to 11.7 with 2 M NaOH. Suspensions were rotated at 40 rpm on a motorized wheel at 24°C for 2 h and centrifuged at 7,500 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was dialyzed (Spectrapor molecular porous membrane with a molecular weight cutoff of 14,000) against ddH2O at 4°C for 12 h. The proteins, in the dialysis tubing, were concentrated by placing them against solid sucrose. The concentration of solubilized proteins was determined by absorption at 280 nm (A280) (27) and by the Lowry method (12); purity was determined by electrophoresis on 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-10% polyacrylamide gels.

Preparation of clay minerals.

The <2-μm fraction of montmorillonite and kaolinite was prepared from bentonite and kaolin, respectively (Fisher Scientific Co.), by differential centrifugation. The clays were made homoionic to calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), or aluminum (Al) (4, 7, 8, 20).

Clay adsorption studies.

Solubilized toxins (0 to 500 μg) were added to 100 μg of homoionic montmorillonite or kaolinite in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) to a total volume of 1 ml. The mixtures of clay and toxins were rotated at 40 rpm on a motorized wheel at 24°C. The concentration of clay and the contact time between the clays and toxins were also varied. In some studies, solubilized toxins (250 μg) were added to 100 μg of homoionic montmorillonite or kaolinite in ddH2O (pH 6.0 or 7.2) or 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0 or 11.0) to a total volume of 1 ml, and the mixtures were rotated at 40 rpm at 24°C for 20 min. The mixtures were centrifuged at 26,300 × g, and the equilibrium supernatant was collected. Loosely bound toxins were desorbed by two washes of the clay-toxin complexes with ddH2O. The concentration of protein in the equilibrium supernatant and washes was determined by A280 and confirmed by the Lowry method (26). The amount of toxin bound to clay was calculated by subtracting the amount of toxins recovered in the equilibrium supernatant and in all washes from the amount of toxins added to the clays.

Mosquito bioassay.

Toxicity of the bound clay-toxin complexes was determined by bioassay with fourth-instar larvae of C. pipiens (Carolina Biological Supply Company, Burlington, N.C.). The larvae were hatched and raised in ddH2O at room temperature for 10 to 12 days and fed mosquito diet. Each clay-toxin complex was resuspended in 4 ml of ddH2O, 1 ml of suspension was added to each of four wells (1.6-cm diameter) on microtiter plates, and four larvae were placed in each well, resulting in 16 larvae per complex. Each bioassay was repeated at least once.

Preparation of antibodies to B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxins.

Polyclonal antibodies (Abs) against the toxins from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis were generated by EnviroLogix Co. (Portland, Maine) in rabbits with ICPs prepared in our laboratory. All Ab preparations gave positive results against the toxins from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis in both dot blot enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) immunodetection.

Dot blot ELISA.

Dot blot ELISA was used to detect the presence of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxins in the clay-toxin complexes. Samples (6 μl) of toxin alone, clay alone, or clay-toxin complexes were spotted onto protein-binding polyvinylidene difluoride membranes in a dot blot apparatus (Hybri-Dot Manifold; GIBCO-BRL Life Technologies, Inc.), to obtain 3-mm-diameter dots in the pattern of a 96-well microtiter plate. To ensure that nonspecific binding of the Abs did not occur, controls were prepared identically to the experimental samples. Controls included ddH2O (pH 6.0 or 7.2) or phosphate buffer (pH 6.0 or 11.0); only montmorillonite or kaolinite homoionic to Ca, Mg, or Al; or bovine serum albumin. Vacuum was applied for 3 to 5 min when all samples were impacted on the membrane. The dot blots were developed by ELISA with appropriate Abs (diluted 1:1,000), goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (diluted 1:300), and H2O2 and 4-chloro-1-naphthol by the methods described by Tapp et al. (23).

ECL immunodetection.

The ECL Western blotting kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was used, and the protocol provided by the company was followed. The proteins were separated on 1% SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred from the gels to Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membranes, and nonspecific binding sites were blocked by immersing the membrane in 5% blocking reagent in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker. The membrane was then rinsed three times with TBS-T, incubated with primary Abs (diluted 1:3,000 in TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and incubated in diluted HRP-labeled donkey anti-rabbit Ab for 1 h. After the membrane was washed with TBS-T, it was incubated with the HRP conjugate for 45 to 60 min and then washed with TBS-T. Interaction between the proteins and Abs was detected by placing the membrane (protein side up) on a piece of Saran Wrap, adding the detection reagents (Amersham), incubating for 1 min, and exposing the membrane to autoradiography film (Hyperfilm ECL) for 15 s.

Statistics.

All experiments were conducted in duplicate, and experiments were repeated at least once. Data are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ECL Western blots of the purified toxins from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis showed the major protein bands with molecular masses ranging from 27 to 135 kDa (Fig. 1), which were identical to bands on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (data not shown). The supernatants from the equilibrium adsorption of the toxins on montmorillonite and kaolinite yielded the same Western blot bands as the toxins before adsorption, indicating no selective adsorption of the different proteins (Fig. 1). In addition, a band between 49 and 61 kDa was present before and after adsorption. This band was probably a product of proteolysis of one of the proteins with a larger molecular mass (14). The bands at 128 and 135 kDa were not resolved and appear as a single band. The presence of the toxins in the clay-toxin complexes was confirmed by dot blot ELISA, and the insecticidal activity of the bound toxins was demonstrated in bioassays with the larvae of C. pipiens (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

ECL Western blots of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis proteins subjected to different treatments. Free B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis proteins (lanes 1 and 8), Ca-montmorillonite-protein complex (lanes 2, 4, and 6), and kaolinite-Ca-protein complex (lanes 3, 5, and 7) were used. Equilibrium adsorption supernatant of the protein complexes before (lanes 2 and 3) and after first (lanes 4 and 5) and second (lanes 6 and 7) washes of the equilibrium adsorption complexes were examined. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated to the left of the blot.

TABLE 1.

Dot blot ELISA of clay-toxin complexes and their insecticidal activity against larvae of C. pipiensa

| Sampleb | Protein concn (μg/ml)c | Immunological assay resultd | % Mortalitye |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | |||

| M-Ca | 219.9 ± 4.25 | •• | 92.5 ± 7.50 |

| K-Ca | 164.1 ± 8.25 | •• | 88.2 ± 11.55 |

| M-Al | 226.0 ± 12.50 | •• | 92.5 ± 7.50 |

| K-Al | 186.3 ± 7.25 | •• | 92.5 ± 7.50 |

| M-Mg | 244.1 ± 3.25 | •• | 100 |

| K-Mg | 189.1 ± 12.25 | •• | 100 |

| Desorption | |||

| 1st wash | |||

| M-Ca | 3.2 ± 1.50 | • | 56.3 ± 11.51 |

| K-Ca | 18.5 ± 2.50 | • | 92.5 ± 7.50 |

| M-Al | 6.6 ± 1.73 | • | 68.5 ± 11.55 |

| K-Al | 11.3 ± 2.81 | • | 72.5 ± 10.50 |

| M-Mg | 8.2 ± 1.98 | • | 70.2 ± 10.50 |

| K-Mg | 13.4 ± 2.67 | • | 74.5 ± 11.55 |

| 2nd wash | |||

| M-Ca | 0.0 | ○ | 12.5 ± 7.50 |

| K-Ca | 2.2 ± 0.45 | ○ | 25.2 ± 7.50 |

| M-Al | 0.0 | ○ | 6.5 ± 6.25 |

| K-Al | 1.4 ± 0.85 | ○ | 12.5 ± 6.25 |

| M-Mg | 0.0 | ○ | 12.5 ± 6.25 |

| K-Mg | 0.0 | ○ | 25.2 ± 10.50 |

Clays without toxin were negative in dot blot ELISA and not toxic to the larvae of C. pipiens (background mortality ranged from 0 to 12.5%). The 50% lethal concentration for the toxin alone was 11.6 ± 0.6 μg.

Clay-toxin complexes (250 μg of protein added to 100 μg of clay) and first and second washes of the equilibrium adsorption complexes: montmorillonite (M) and kaolinite (K) homoionic to calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), or aluminum (Al).

Amount of protein on the clay after equilibrium adsorption and desorbed by first and second washes, determined by the Lowry method. Values are given as means ± standard errors of the means.

Dot blot ELISA was done to detect the toxins in the complexes. Symbols: ••, strong positive; •, weak positive; ○, negative. The lower limit of detection of the toxins was 0.098 μg.

Mortality determined by bioassay against fourth-instar larvae of C. pipiens. Values are given as means ± standard errors of the means.

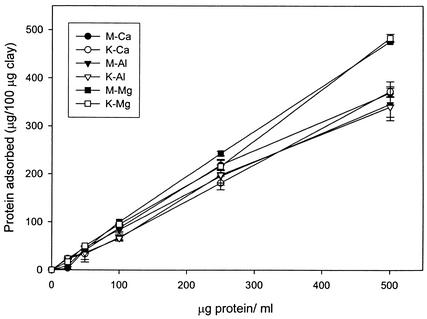

Adsorption at equilibrium was rapid (68 to 96% of the toxins adsorbed within 30 min, the shortest time measured) and greater on montmorillonite than on kaolinite (Fig. 2). No saturation of the clays occurred even after adding 500 μg of protein to 100 μg of clay (Fig. 3), indicating multilayer adsorption of the proteins (20).

FIG. 2.

Rate of adsorption of the toxins from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis on montmorillonite (M) and kaolinite (K) homoionic to calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and aluminum (Al). The adsorption mixture contained 100 μg of clay and 250 μg of solubilized toxins in phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) in a total volume of 1 ml. Data are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means (error bars).

FIG. 3.

Adsorption of the toxins from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis on montmorillonite (M) and kaolinite (K) homoionic to calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), or aluminum (Al) as a function of protein concentration. There was 100 μg of clay per ml of adsorption mixture. The contact time was 30 min. Data are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means (error bars).

When the concentration of toxins was kept constant and the concentration of clay was varied, adsorption increased with an increase in the amount of clay and then decreased with the largest amounts of clay (Fig. 4). Binding of the toxins decreased as the pH was increased from 6 to 11. There was 35 to 40% more binding in phosphate buffer at pH 6 than in ddH2O at pH 6, and there was 59 to 66% more binding in phosphate buffer at pH 6 than in ddH2O at pH 7.2 (Table 2). Therefore, most adsorption and binding experiments were conducted in phosphate buffer at pH 6. However, mortality was essentially 100% at all pH values.

FIG. 4.

Adsorption of the toxins from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis on different concentrations of montmorillonite (M) homoionic to calcium (Ca) or magnesium (Mg). There was 250 μg of toxin per ml of adsorption mixture. The contact time was 30 min. Data are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means.

TABLE 2.

Effect of pH on binding of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxins on montmorillonite (M) or kaolinite (K) homoionic to calcium (Ca)a and on mortality of clay-bound toxins to larvae of C. pipiens

| Medium | M-Ca

|

K-Ca

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Bindingb | % Mortalityc | % Binding | % Mortality | |

| Water | ||||

| pH 7.2 | 24.4 ± 0.14 | 92.5 ± 7.50 | 16.6 ± 0.81 | 88.5 ± 11.55 |

| pH 6.0 | 51.9 ± 5.20 | 100 | 40.5 ± 7.12 | 92.5 ± 7.50 |

| 0.2 M Phosphate buffer | ||||

| pH 6.0 | 90.9 ± 6.42 | 100 | 75.5 ± 2.43 | 100 |

| pH 11.0 | 58.5 ± 3.62 | 100 | 42.3 ± 1.50 | 100 |

250 μg of toxin was added to 100 μg of clay suspended in 1 ml of double-distilled water (pH 6.0 or 7.2) or 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0 or 11.0).

The percent binding of toxins on the clays was calculated by subtracting the amount of toxins recovered in the equilibrium supernatant and in all washes from the amount of toxins added to the clays. Values are given as means ± standard errors of the means.

Mortality determined by bioassay against the fourth-instar larvae of C. pipiens. Values are given as means ± standard errors of the means. Clays and medium without toxins were not toxic to the larvae of C. pipiens (background mortality ranged from 0 to 12.5%).

Only 2 to 12% of the toxins adsorbed at equilibrium was desorbed by one or two washes with ddH2O (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Additional washings desorbed no more toxin, indicating that 88 to 98% of the adsorbed toxins was tightly bound to the clays similar to what has been observed with the toxins from other subspecies of B. thuringiensis (22-24). ECL Western blots of the washes indicated no major protein bands (Fig. 1), but some of the washes were toxic to the larvae of C. pipiens (Table 1). The sensitivity of bioassays is apparently greater than that of Western blots, as has also been observed with the toxins from other subspecies of B. thuringiensis (23, 26).

The larger amount of toxins adsorbed by montmorillonite than by kaolinite was probably a reflection of the significantly higher specific surface area and cation-exchange capacity of montmorillonite, a swelling 2:1 Si-Al clay mineral, than of kaolinite, a nonswelling 1:1 Si-Al clay (20). The cation to which the clays were homoionic had little influence on the equilibrium adsorption of the toxins on the clays (Table 1). The structure of the toxins did not appear to have been modified as the result of their binding to the clay, as indicated by the following: (i) no changes in the mobility of the desorbed toxins on SDS-polyacrylamide gels; (ii) positive ELISA results; and (iii) toxicity of the clay-toxin complexes to the larvae of C. pipiens. After 45 days in nonsterile water, the toxicity of clay-bound toxins was significantly higher (mortality of 63% ± 12.7%) than that of free toxins (mortality of 25% ± 12.5%), indicating that binding of the toxins to clay reduced their susceptibility to biodegradation, as has been shown with toxins from other subspecies of B. thuringiensis (10, 22). However, the higher mortality of clay-bound toxins could have reflected greater ingestion of bound toxins than of free toxins (18).

Larvae of mosquitoes and some other dipterans are filter feeders, and toxins bound to clay may be more effective for their control and pose less risk to the environment than transgenic cyanobacteria containing genes from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (2, 11, 15, 28, 29), which could transfer the toxin genes to other bacteria. Moreover, most clays in the micrometer size range form colloidal suspensions that sediment slowly (e.g., it required >20,000 × g to sediment these clay-toxin complexes), indicating that such complexes would remain suspended in the water column longer than sprayed commercial preparations of the ICPs of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Hence, both surface-feeding (e.g., Anopheles species) and bottom-feeding (e.g., C. pipiens used in these studies) larvae might be controlled by these complexes. Extensive field studies are obviously required to establish the efficacy of clay-toxin complexes in controlling mosquitoes and other dipterans in aquatic systems.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (most recently R826107-01) and the NYU Research Challenge Fund.

The opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or NYU Research Challenge Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson, A. 2002. Sporulation and delta-endotoxin synthesis by Bacillus thuringiensis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:417-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boussiba, S., X. Q. Wu, E. Ben-Dov, A. Zarka, and A. Zaritsky. 2000. Nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria as gene delivery system for expressing mosquitocidal toxins of Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. israelensis. J. Appl. Phycol. 12:461-467. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crickmore, N., D. R. Zeigler, J. Feitelson, E. Schnepf, J. J. Van Rie, D. Lereclus, J. Baum, and D. H. Dean. 1998. Revision of the nomenclature for the Bacillus thuringiensis pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dashman, T., and G. Stotzky. 1982. Adsorption and binding of amino acids on homoionic montmorillonite and kaolinite. Soil Biol. Biochem. 14:447-456. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Entwistle, P. F., J. S. Cory, M. J. Bailey, and S. Higgs (ed.). 1993. Bacillus thuringiensis, an environmental biopesticide: theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 6.Feitelson, J. S., J. Payne, and L. Kim. 1992. Bacillus thuringiensis: insects and beyond. Bio/Technology 10:271-275. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fusi, P., G. Ristori, L. Calamai, and G. Stotzky. 1989. Adsorption and binding of protein on “clean” (homoionic) and “dirty”(coated with Fe oxyhydroxides) montmorillonite, illite, and kaolinite. Soil Biol. Biochem. 21:911-920. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harter, R. D., and G. Stotzky. 1971. Formation of clay-protein complexes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. Proc. 35:383-389. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höfte, H., and H. R. Whiteley. 1989. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol. Rev. 53:242-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koskella, J., and G. Stotzky. 1997. Microbial utilization of free and clay-bound insecticidal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis and their retention of insecticidal activity after incubation with microbes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3561-3568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lluisma, A. O., N. Karmacharya, A. Zarka, E. Ben-Dov, A. Zaritsky, and S. Boussiba. 2001. Suitability of Anabaena PCC7120 expressing mosquitocidal toxin genes from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis for biotechnological application. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 57:161-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowry, O. H., N. R. Rosebough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randel. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manasherob, R., A. Zaritsky, E. Ben-Dov, D. Saxena, Z. Barak, and M. Einav. 2001. Effect of accessory proteins P19 and P20 on cytolytic activity of Cyt1Aa from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis in Escherichia coli. Curr. Microbiol. 43:355-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfannenstiel, M. A., E. J. Ross, V. C. Kramer, and K. W. Nickerson. 1984. Toxicity and composition of protease-inhibited Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis crystals. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 21:39-42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rujan, T., and W. Martin. 2001. How many genes in Arabidopsis come from cyanobacteria? An estimate from 386 protein phylogenies. Trends Genet. 17:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxena, D., and G. Stotzky. 2001. Bt toxin uptake from soil by plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena, D., and G. Stotzky. 2002. Bt toxin is not taken up from soil or hydroponic culture by corn, carrot, radish, or turnip. Plant Soil 239:165-172. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnell, D. J., M. A. Pfannenstiel, and K. W. Nickerson. 1984. Bioassay of solubilized Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis crystals by attachment to latex beads. Science 16:1191-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnepf, E., N. Crickmore, J. Van Rie, D. Lereclus, J. Baum, J. Feitelson, D. R. Zeigler, and D. H. Dean. 1998. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:775-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stotzky, G. 1986. Influence of soil mineral colloids on metabolic processes, growth, adhesion, and ecology of microbes and viruses, p. 305-428. In P. M. Huang and M. Schnitzer (ed.), Interactions of soil minerals with natural organics and microbes. Soil Science Society of America, Madison, Wis.

- 21.Stotzky, G. 2000. Persistence and biological activity in soil of insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis and of bacterial DNA bound on clays and humic acids. J. Environ. Qual. 29:691-705. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stotzky, G. 2001. Release, persistence, and biological activity in soil of insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis, p. 187-222. In D. K. Letourneau and B. E. Burrows (ed.), Genetically engineered organisms: assessing environmental and human health effects. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 23.Tapp, H., and G. Stotzky. 1995. Dot blot enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for monitoring the fate of insecticidal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:602-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tapp, H., and G. Stotzky. 1995. Insecticidal activity of the toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies kurstaki and tenebrionis adsorbed and bound on pure and soil clays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1786-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapp, H., and G. Stotzky. 1997. Monitoring the fate of insecticidal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis in soil with flow cytometry. Can. J. Microbiol. 43:1074-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tapp, H., and G. Stotzky. 1998. Persistence of the insecticidal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30:471-476. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tapp, H., L. Calamai, and G. Stotzky. 1994. Adsorption and binding of the insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki and subsp. tenebrionis on clay minerals. Soil Biol. Biochem. 26:663-679. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Hannen, E. J., G. Zwart, M. P. van Agterveld, H. J. Gons, J. Ebert, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1999. Changes in bacterial and eukaryotic community structure after mass lysis of filamentous cyanobacteria associated with viruses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:795-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiaoqiang, W., S. J. Vennison, L. Huirong, E. Ben-Dov, A. Zaritsky, and S. Boussiba. 1997. Mosquito larvicidal activity of transgenic Anabaena strain PCC 7120 expressing combinations of genes from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4971-4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]