Abstract

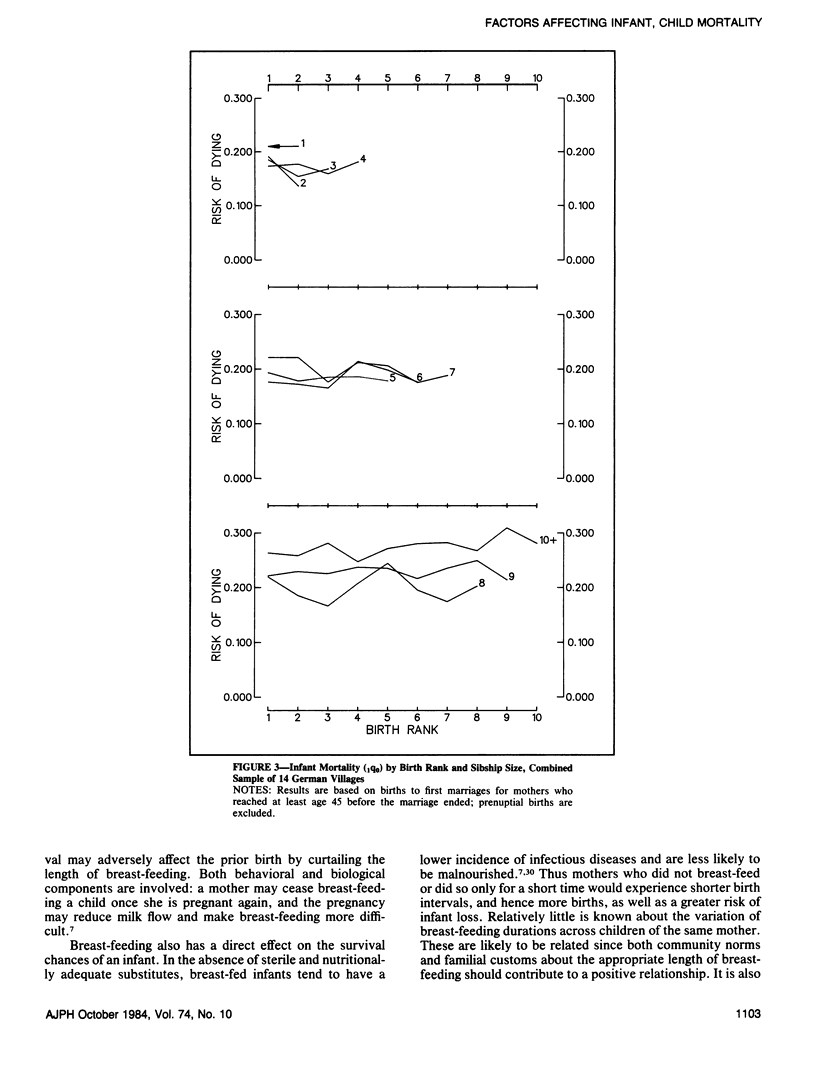

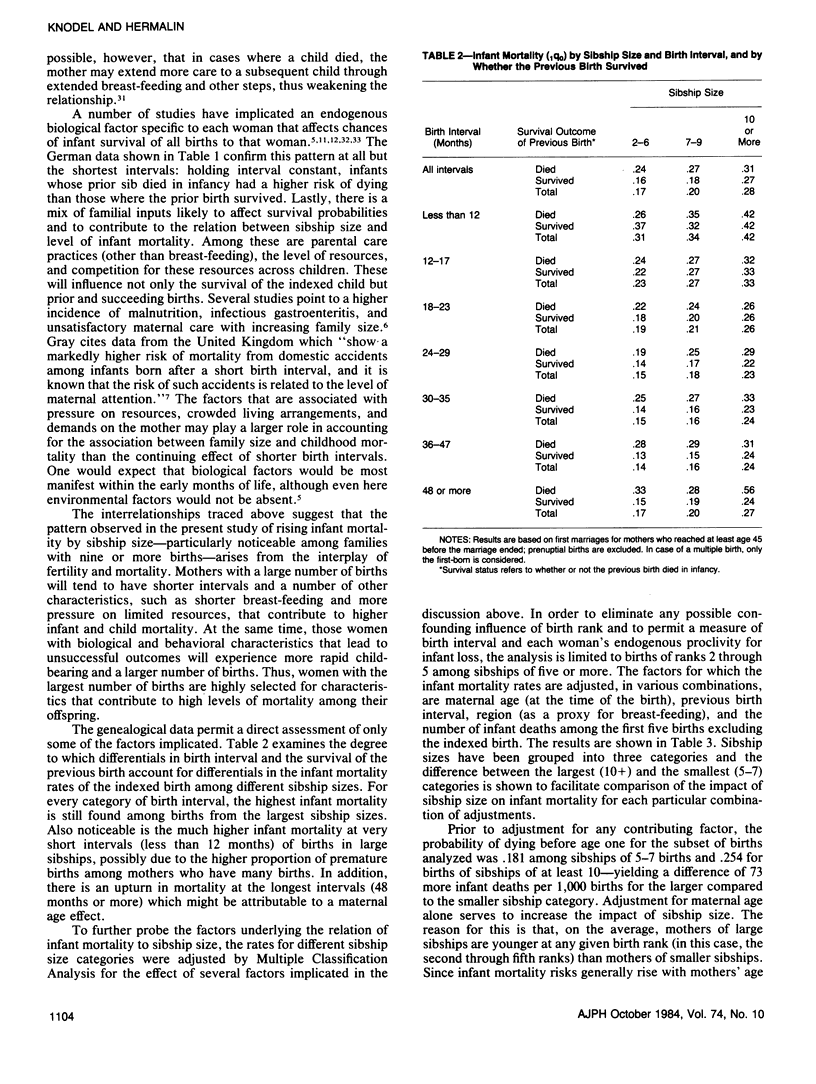

There has been long-standing interest in the effects of maternal age, birth rank, and birth spacing on infant and child mortality. Contradictory inferences about the role of these factors have arisen on occasion because of the absence of adequate controls, the use of cross-sectional or incomplete reproductive histories, and inattention to the effect of family size goals and birth limitation practices. This study analyzes completed reproductive histories for German village populations in the 18th and 19th centuries, a period when deliberate fertility control was largely absent. Our results confirm previous studies of the association of infant mortality with maternal age, although in the present data these differentials are largely limited to neonatal mortality. They also confirm the importance of birth interval as a factor in infant mortality. Sibship size is positively related to infant mortality even when birth rank is controlled. However, once sibship size is controlled, there are no systematic differences in infant and child mortality by birth order. The mechanisms relating sibship size and mortality are explored.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bakketeig L. S., Hoffman H. J. Perinatal mortality by birth order within cohorts based on sibship size. Br Med J. 1979 Sep 22;2(6192):693–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6192.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billewicz W. Z. Some implications of self-selection for pregnancy. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1973 Feb;27(1):49–52. doi: 10.1136/jech.27.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. E. Childhood mortality, family size and birth order in pre-industrial Europe. Demography. 1975 Feb;12(1):35–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEADY J. A., STEVENS C. F., DALY C., MORRIS J. N. Social and biological factors in infant mortality. IV. The independent effects of social class, region, the mother's age and her parity. Lancet. 1955 Mar 5;268(6862):499–503. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(55)90284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J., De Vos S. Preferences for the sex of offspring and demographic behavior in eighteenth and nineteenth-century Germany: an examination of evidence from village genealogies. J Fam Hist. 1980 Summer;5(2):145–166. doi: 10.1177/036319908000500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J. From natural fertility to family limitation: the onset of fertility transition in a sample of German villages. Demography. 1979 Nov;16(4):493–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J., Wilson C. The secular increase in fecundity in German village populations: an analysis of reproductive histories of couples married 1750-1899. Popul Stud (Camb) 1981 Mar;35(1):53–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winikoff B. The effects of birth spacing on child and maternal health. Stud Fam Plann. 1983 Oct;14(10):231–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J. D. Population pressure on families: family size and child spacing. Rep Popul Fam Plann. 1971 Aug;9:404–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YERUSHALMY J., BIERMAN J. M., KEMP D. H., CONNOR A., FRENCH F. E. Longitudinal studies of pregnancy on the island of Kauai, Territory of Hawaii. I. Analysis of previous reproductive history. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1956 Jan;71(1):80–96. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(56)90682-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]