Abstract

Anaerobic bacteria insensitive to chlortetracycline (64 to 256 μg/ml) were isolated from cecal contents and cecal tissues of swine fed or not fed chlortetracycline. A nutritionally complex, rumen fluid-based medium was used for culturing the bacteria. Eight of 84 isolates from seven different animals were identified as Megasphaera elsdenii strains based on their large-coccus morphology, rapid growth on lactate, and 16S ribosomal DNA sequence similarities with M. elsdenii LC-1T. All eight strains had tetracycline MICs of between 128 and 256 μg/ml. Based on PCR assays differentiating 14 tet classes, the strains gave a positive reaction for the tet(O) gene. By contrast, three ruminant M. elsdenii strains recovered from 30-year-old culture stocks had tetracycline MICs of 4 μg/ml and did not contain tet genes. The tet genes of two tetracycline-resistant M. elsdenii strains were amplified and cloned. Both genes bestowed tetracycline resistance (MIC = 32 to 64 μg/ml) on recombinant Escherichia coli strains. Sequence analysis revealed that the M. elsdenii genes represent two different mosaic genes formed by interclass (double-crossover) recombination events involving tet(O) and tet(W). One or the other genotype was present in each of the eight tetracycline-resistant M. elsdenii strains isolated in these studies. These findings suggest a role for commensal bacteria not only in the preservation and dissemination of antibiotic resistance in the intestinal tract but also in the evolution of resistance.

Tetracycline antibiotics inhibit bacterial growth by preventing protein synthesis. Tetracyclines bind to bacterial ribosomes, interfering with the association of aminoacyl-tRNAs with ribosomes (13, 43). Due to their efficacy against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and low toxicity for eukaryotic cells, tetracycline is used in a long list of human clinical and nonclinical applications for controlling bacterial growth (13). Additionally, their low costs have made tetracyclines attractive for agricultural use to prevent diseases of plants and animals and to promote animal growth (13, 40). In a survey of 712 U.S. swine farms between 1989 and 1991, tetracycline antibiotics (chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline, and tetracycline) were the most commonly fed antimicrobials, especially to swine in the growth phase (20 to 90 kg) of development (17).

Widespread use of tetracyclines has, not surprisingly, led to widespread resistance. Several different mechanisms of bacterial resistance to tetracycline have been reported. Nonspecific tetracycline resistance can result from general efflux mechanisms (13). Specific tetracycline resistance is often associated with tetracycline efflux proteins and ribosomal protection proteins and less commonly with 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) mutations and enzyme inactivation of the antibiotic (13). Recently a Vibrio tetracycline resistance mechanism (Tet34) was linked to an enzyme of purine metabolism (45), although biochemical evidence for the activity is lacking.

Over 30 classes of resistance determinants specific for tetracycline have been described (13, 57). The tet classes are defined by amino acid sequence similarity of the proteins they encode (33). Classes of tet genes are identified by DNA-DNA hybridization, PCR assays, or both (5, 6, 8, 9, 12, 29, 44, 48, 49, 54).

The contributions of commensalistic bacteria to the dissemination and persistence of antibiotic resistance in the mammalian intestinal tract are only beginning to be appreciated (2, 8, 37, 54). In that tetracycline has been commonly added to swine feed for disease prevention and growth promotion purposes, the microbial ecosystem of the swine intestinal tract would seem a good choice for investigating tet gene ecology. As a basis for these investigations, we have begun to analyze tetracycline-resistant anaerobes and their resistance mechanisms. In this report we describe the isolation and characterization of tetracycline-resistant Megasphaera elsdenii swine strains and the discovery of interclass, mosaic tetracycline resistance determinants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PCR amplification of tet and rrs genes.

PCR primers for ribosomal protection protein genes tet(M), tet(O), tet(S), tet(T), and tet(W) were described previously (6). PCR primers for genes encoding tetracycline efflux proteins (Table 1) were based on a comparative analysis of their sequences. GenBank accession numbers for the sequences are X6137, X00006, and X75761 for tet(A); V00611, AF223162, AF162223, J01830, and Y19113 for tet(B); J01749 and NC002109 for tet(C); X65876, D16162, and L06798 for tet(D); L06940 and Y19116 for tet(E); S52437, AF071555, Y19118, AF133139, and AF133140 for tet(G); U00792 and Y16103 for tet(H), U36910, M16127, and S67449 for tet(K); and X51366, M63891, D12567, D00006, D26045, U17153, X15669, and X60828 for tet(L). All PCR assays for tet genes were validated by using bacterial strains containing known tet determinants (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

PCR assays for tetracycline resistance genesa

| Gene | PCR primers | Species (plasmid) | Strain sourceb (designation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux resistance genes | |||

| tetA | CCTGCGCGATCTGGTTCACT | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (RP1) | NCTC (NC050076) |

| GCCAGCGAGACGAGCAAGA | |||

| tetB | TTTCACCGCATAGTCCCTTT | E. coli (R222Jap) | NCTC (NC050019) |

| CGGGAATTTGGCCTATCAAT | |||

| tetC | GCCTATATCGCCGACATCAC | E. coli (pSC101) | NCTC (NC050436) |

| GTAGGTTGAGGCCGTTGAGC | |||

| tetD | CATCTGCCGTTTGTCATTGC | E. coli (RA1) | NCTC (NC050073) |

| ACAGCGCCAGAGGTTTAAGC | |||

| tetE | GCTGACGGTTGTGGCCTATT | E. coli (pSL1456) | NCTC (NC050273) |

| CGCGGGTTGCACTATACAAA | |||

| tetG | TTCAAGCCGGCTTGGAGAG | E. coli (pJA8122) | MR |

| TTGTTTGAGAGCATTGCCTGC | |||

| tetH | AGCGCTTGTTGCCAATAGGAC | E. coli (pVM112) | MR |

| CCAAAGACATACCGATAGAAGTTGTG | |||

| tetK | GTACAAGGAGTAGGATCTGCTGCAT | Staphylococcus aureus (pT181) | NCTC (NC050585) |

| TTATTCCCCCTATTGAAGGACCTAA | |||

| tetL | TGAACGTCTCATTACCTGATATTGC | Eaterococcus faecalis | NADC (TspigL) |

| TTTGGAATATAGCGAGCAAC | |||

| M. elsdenii mosaic tet genesc | |||

| tet(O) product 1 | ACGGARAGTTTATTGTATACC | E. coli (pAT121) | NCTC (NC050500) |

| TGGCGTATCTATAATGTTGAC | |||

| tet(W) product 2 | GAATTCTTGCCCATGTAGAC | E. coli (pIE1120) | MR |

| AAGAGCGGTACACCTCCG | |||

| Mosaic tet product 3 | ACGGARAGTTTATTGTATACC | M. elsdenii | This study (7-11, 14-14) |

| AAGAGCGGTACACCTCCG | |||

| tet(O) product 4 | TTCGGAAATTATAGTGAAGCA | E. coli (pAT121) | NCTC (NC050500) |

| CGGAACATACATCTCTGTGA | |||

| tet(W) product 5 | CTGCGGGATACGGTGGC | E. coli (pIE1120) | MR |

| ACCTCCAACTGCACCCGG | |||

| Mosaic tet product 6 | GCCCCCCTCCCCATGC | M. elsdenii | This study (7-11) |

| AGGGAGCGGCTCTATGGA | |||

| Mosaic tet product 7 | CTGGGATACTTGAACCAGAGT | M. elsdenii | This study (14-14) |

| GGCTGGTATCCTTTTAACTC | |||

| tet(O) product 8 | TCAGATAAAGAATGACGAGGT | E. coli (pAT121) | NCTC (NC050500) |

| GGCTGGTATCCTTTTAACTC | |||

| tet(W) product 9 | CCAGGTAAAAAAGGATGAAGT | E. coli (pIE1120) | MR |

| GCCTGATATCCTTTCAGCTC |

Gene target, PCR primers, validation strain, and strain source for PCR assays used to screen intestinal bacteria in these studies. Primer pairs are listed as forward (top) and reverse (bottom) beginning with their 5′ nucleotide positions.

NCTC, National Culture Type Collection, Public Health Laboratory Service, London; NADC, National Animal Disease Center; MR, Marilyn Roberts, University of Washington.

PCR primers used to analyze M. elsdenii mosaic tet genes. Products of the PCR amplifications and corresponding tet gene regions are depicted in Fig. 4.

Bacterial rrs V3 variable regions were amplified by using the forward PCR primer 5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG and the reverse primer 5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG (39). Primers for amplifying the nearly complete rrs gene were forward 5′-GAGAGTTTGATC(C/A)TGGCTCAG and reverse 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT (10). ClustalW and other programs in the Vector NTI Suite version 5.5 (Informax, Inc.) were used for accessing and comparing gene sequences in GenBank. Oligo version 6.0 (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc.) was used to design PCR primers. All PCR primers used throughout these studies were synthesized at the Nucleic Acid Facility at Iowa State University.

For preliminary identification of unknown bacteria cultured from swine ceca, a bacterial colony was stabbed with a sterile toothpick, and the cells were suspended in 50 μl of sterile distilled water. This cell suspension was used as a source of target DNA in PCRs. For PCR amplification of cloned bacterial strains, broth cultures in the exponential phase of growth (optical density at 620 nm [OD620] approximately 1.0, 18-mm culture tubes) were washed once and resuspended in equal volumes of sterile distilled water, diluted 1/10 in distilled water, and the bacterial suspensions were stored at −20°C until use.

For PCR amplification reactions, a final volume of 50 μl contained 5 μl of cell suspension (target DNA), 1 × PCR buffer II (Perkin-Elmer), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin, 0.25 μM each primer, and 1.25 U of AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). An initial hot start of 10 min at 95°C was followed by 30 to 35 cycles consisting of 1 min of denaturation at 95°C, 1 min of annealing at the appropriate temperature and 2 min of extension at 72°C. The last cycle was followed by an 8-min extension at 72°C. For amplifying the tet(B), tet(D), tet(H), tet(K), tet(L), and tet(S) genes, the rrs V3 region, and nearly complete rrs sequences, the annealing temperature was 50°C. For tet(A), tet(E), tet(G), and tet(M), the annealing temperature was 55°C, and for tet(C), tet(O), tet(Q), and tet(W), an annealing temperature of 60°C was used. An MJ Research Dyad thermal cycler with independent block heater control was used for amplification reactions.

DNA products in 10-μl samples of the PCR assays were detected and analyzed by their electrophoretic migration on 4% agarose gels in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (53).

In parallel with PCR assays for tet genes, control assays for the rrs V3 region were always included, as a means of confirming the integrity of the target DNA.

Swine origin and management.

Seven swine were purchased from farm A with no history of antibiotic use over the previous 2 years. Six swine were obtained from farm B, which used feed formulated with chlortetracycline (400 g/ton) to prevent disease. Animals were mixed breed, both sexes, in the early grower phase of their life cycle (40 to 50 kg) at the start of the experiment. At the National Animal Disease Center, the two groups were housed separately in climate-regulated, controlled-access rooms. The swine were allowed to acclimate for 10 days before the beginning of sampling. Animals were supplied water ad libitum and fed their original farm diet (1.5 kg/animal/day). Feed composition information from the farmers was not available. Feed samples were assayed for chlortetracycline (7).

Processing of cecal contents and tissues.

Three animals were sampled every week. Each animal was euthanized by intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbitol (26% solution; 1 ml/4.5 kg; Sleepaway, Fort Dodge Laboratories) followed by exsanguination in accordance with National Animal Disease Center Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. The cecum was surgically exposed and tied off by string ligatures at the ileocecal junction. The cecum was excised by cutting between the ligatures, placed in a plastic bag, deposited in an ice bath, and transported within 30 min to the laboratory. In the laboratory, the blind tip of the cecum was cut off, and cecal contents were drained into a sterile 600-ml Ehrlenmeyer beaker. The beaker, covered with a loosely fitted aluminum foil hood, was immediately transferred into a Coy anaerobic chamber inflated with a gas mix of 85% N2-10% CO2-5% H2. Inside the chamber, the contents were mixed by manual stirring, and a 5-ml sample was placed into 100 ml of sterile HI broth (Difco heart infusion broth) in a Waring blender jar. Another 5-ml sample was deposited into a tared weighing container to determine its wet weight. The contents were blended twice for 10 s at the maximum blender speed with a 10-s pause between blendings.

Simultaneously with the processing of cecal contents, 5 disks, 12 mm in diameter, were cut from washed cecal tissues and blended in 100 ml of HI broth in an anaerobic chamber to remove tissue-associated bacteria, as described (4).

Isolation of chlortetracycline-insensitive anaerobic bacteria from cecal samples.

Within Coy anaerobic chambers, a 0.5-ml sample of either a cecal tissue or cecal contents homogenate was serially diluted 10-fold to 10−8 in tubes of HI broth. Samples (0.1 ml) of appropriate dilutions were plated on RTC agar medium (described below) containing chlortetracycline at final concentrations of 0, 4, 16, 64, 128, and 256 μg/ml. After 5 days of incubation at 38°C within the chamber incubator, colonies were counted. Strains growing on RTC plates containing 64 or 256 μg of chlortetracycline/ml were isolated by subculturing single colonies on RTC agar plates containing the same chlortetracycline concentration. After the second subculture, a sample of an isolated colony was taken with a sterile toothpick for PCR amplification as described above. Additionally, a block of agar containing three to four identical-appearing colonies was aseptically cut from the agar plate and deposited into a Nunc cryovial. The vial contained 1 ml of HI broth with dimethyl sulfoxide (10% vol/vol, final concentration) as a cryoprotectant. The sealed vial was removed from the anaerobic chamber and stored at −70°C.

Culture media.

HI broth for blending and diluting cecal samples was prepared aerobically, sterilized by autoclaving, and immediately placed into the Coy chamber at least 48 h before use. PY broth (27) for M. elsdenii strains contained glucose or lactate (1% wt/vol, final concentration).

RTC medium was modified from CCA medium used to culture swine cecal anaerobes (4). RTC medium contained (per liter): clarified bovine rumen fluid, 300 ml; salts A, 200 ml; salts B, 200 ml; trypticase-peptone (BBL), 2 g; glycerol, 1.25 g; hemin solution, 10 ml; carbohydrate solution, 2.5 ml; resazurin solution (0.1%, wt/vol), 1 ml; l-cysteine HCl, 1 g; and distilled water, 280 ml. The medium (adjusted to pH 7.0) was gently heated under N2 gas until the resazurin indicator became colorless and then either dispensed anaerobically into tubes for autoclaving or autoclaved and used to make agar plates. For solid agar medium, Difco Noble agar was added at a final concentration of 1.2% (wt/vol).

Clarified rumen fluid consisted of freshly collected rumen fluid filtered through a layer of cheesecloth, centrifuged at 14,000 × g to remove particulates, autoclaved, and stored at 5°C as described previously (4). Salts A contained 0.45 g of CaCl2 and 0.45 g of MgSO4 in 1 liter of distilled water. Salts B contained 2.25 g of KH2PO4, 2.25 g of K2HPO4, 4.5 g of NaCl, and 4.5 g of (NH4)2SO4 per liter of distilled water. Hemin solution was made by dissolving 50 mg of hemin in 1 ml of NaOH and diluting to 100 ml with distilled water. The stock carbohydrate solution contained 10 g each of d-fructose, maltose, d-glucose, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, d-ribose, cellobiose, and l-arabinose in 100 ml of distilled water and was sterilized by autoclaving.

A filter-sterile stock solution of chlortetracycline (3.2 mg/ml of water) was diluted and added to the media before pouring the agar plates. Aerobically prepared RTC agar plates were put into the anaerobic chamber at least 48 h before use, at which time the resazurin indicator in the medium had become colorless. Throughout these studies, all media and solutions containing tetracycline antibiotics were protected from light.

Strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains containing known tet determinants were used as validation strains and as control strains in PCR assays. The strains and their suppliers are given in Table 1. Culture media and incubation conditions followed the recommendations of the suppliers.

M. elsdenii strains LC1T, B159, and T81 were recovered from National Animal Disease Center stock cultures frozen in 1972. All three strains were low-passage subcultures of isolates from ovine or bovine rumen samples in the mid-1950s to early 1960s. Strain LC1T is the M. elsdenii type strain. The strains were cultured anaerobically in tubes of PY broth (10 ml/tube) containing 1% (wt/vol) glucose.

Strains of obligately anaerobic, large cocci isolated in these studies (see Table 3) were initially cultured in RTC medium containing 64 or 256 μg of chlortetracycline/ml. After they were identified as M. elsdenii strains, they were routinely cultured in PY broth containing glucose. In experiments testing growth on lactate, sodium d,l-lactate at 1% wt/vol (final concentration) replaced glucose.

TABLE 3.

M. elsdenii strain characteristics

| Straina | Animal or sample | V3 sequence similarityb to RLC-1 (%) | Growth on lactate (OD620) | MIC (μg/ml)c

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tet | Ctc | Otc | Dox | ||||

| LC-1T | Ovine | 100 | 1.75 | 4 | 4-8 | 8-16 | 1 |

| B159 | Bovine | ND | 1.7 | 4 | 4-8 | 8-16 | 1 |

| T81 | Ovine | ND | 1.75 | 4 | 2-4 | 8-16 | 1-2 |

| 2-9 | Swine cecal contents (farm A) | 98.2 | 1.8 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 64 |

| 4-13 | Swine cecal contents (farm A) | 99.4 | 1.7 | 128 | >256 | 256 | 64 |

| 7-11 | Swine cecal contents (farm A) | 98.9 | 1.8 | 128 | >256 | 256 | 64 |

| 7-12 | Swine cecal contents (farm A) | 98.9 | 1.6 | 128 | >256 | 256 | 64 |

| 14-14 | Swine cecal tissues (farm B) | 99.4 | 1.85 | 256 | >256 | >256 | 64 |

| 15-5 | Swine cecal tissues (farm B) | 98.9 | 1.8 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 64 |

| 19-3 | Swine cecal tissues (farm B) | 98.9 | 1.55 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 64 |

| 20-11 | Swine cecal tissues (farm B) | 98.9 | 1.4 | 128 | >256 | 256 | 64 |

| Bacillus fragilis ATCC 25285 (TcS) | 1-2 | 4 | 8-16 | 1 | |||

| Bacillus thetaiotaomicron ATCC 29741 (Tcr) | 64 | 128 | 64 | 32-64 | |||

M. elsdenii strains LC-1T, B159, and T81 were obtained from stock cultures. Additional M. elsdenii strains were isolated in these studies. Bacteroides strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection for use as reference strains in tetracycline MIC assays (41).

Percent sequence similarity with M. elsdenii LC-1T (U95027) in the 16S rDNA V3 region. ND, not determined.

Tetracycline (Tet), chlortetracycline (Ctc), oxytetracycline (Otc), and doxycycline (Dox) concentrations expressed per milliliter of medium.

In all experiments, M. elsdenii cells and cultures were maintained under anaerobic conditions, either within a Coy flexible film anaerobic chamber inflated with a mixture of 85% N2-10% CO2-5%H2 or by typical anaerobic techniques using sealed culture vessels with an O2-free N2 atmospheres (28). For long-term preservation, M. elsdenii cultures in the late exponential growth phase (2 × 108 to 5 × 108 CFU/ml) were harvested by centrifugation (5°C, 3,000 × g, 10 min). The cell pellets were resuspended in the original culture volume of fresh medium containing 10% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide, and 1-ml volumes in Nunc cryovials were frozen at −70°C.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis programs were accessed through the web site (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/html/) of the Ribosomal Database Project II (RDPII) (35). The 16S rRNA V3 sequences (160 bp between primers) of the swine bacterial isolates were analyzed with the Sequence Match version 2.7 program of Niels Larsen. Nearly complete 16S rDNA sequences (1,475 bp) of strains 2-9, 4-13, and 7-11 were analyzed by the same program to identify species phylogenetically related to those strains. A distance matrix for these three strains and their nearest relatives in the database was generated with the DNADist program in Felsenstein's Phylip 3.5C. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the Neighbor program in Phylip.

Antibiotic MIC assays.

Antibiotic MICs for M. elsdenii strains were determined by the agar dilution method, with Brucella blood agar base medium with supplements (41). Bacteroides fragilis ATCC 25285 (tetracycline sensitive) and B. thetaiotaomicron ATCC 29741 (tetracycline resistant) cultures were used as reference strains. Megasphaera and Bacteroides cells were cultured in RTC broth containing (for resistant strains) 10 μg of chlortetracycline/ml. Bacteria in the exponential growth phase (M. elsdenii culture OD620 = 1.0, equivalent to 5 × 107 CFU/ml; Bacteroides culture OD620 = 0.6, equivalent to 2 × 108 to 4 × 108 CFU/ml) were harvested by centrifugation, washed once in an equal volume of cold anaerobic sodium phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0), and resuspended in buffer to give a final concentration of 2 × 107 CFU/ml. In an anaerobic chamber, 5-μl aliquots of this suspension were spotted onto Brucella blood agar plates containing antibiotic concentrations of 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μg/ml. All MIC determinations were performed at least twice. Stock solutions (5.12 mg/ml) of chlortetracycline, tetracycline, and doxycycline were made in distilled water and filter sterilized. A stock solution of oxytetracycline (5.12 mg/ml of ethanol) was used without filter sterilization.

Antibiotic MICs for E. coli strains carrying M. elsdenii tet genes were determined by the agar dilution method for aerobic bacteria with Mueller-Hinton agar (42). E. coli ATCC 25922 (tetracycline sensitive) was used as a reference strain.

Cloning M. elsdenii strain 7-11 and 14-14 tetracycline resistance genes.

The tetracycline resistance genes of M. elsdenii strains 7-11 and 14-14 were amplified by PCR with two primer pairs designated Str and Fus. Primer design was based on the tet(O) gene of Campylobacter jejuni (GenBank accession number M18896). The forward Str primer was 5′-AAAAAAGGATCCATGTAATTTTATATGCCCGAAAA, annealing to a region 107 bp upstream of the start of the C. jejuni tet(O) coding sequence. The Fus forward primer was 5′-AAAAAAGGATCCAATGAAAATAATTAACTTAGGCATTC, annealing to the start of the C. jejuni tet(O) coding sequence. The reverse primer, 5′-AAAAAAGAATTCATCATAATTATCTCTAATCCTTC, annealing to a region 36 bp downstream of the end of tet(O) and was the same for both Str and Fus pairs. Each primer contained a restriction site (underlined) at the 5′ end (BamHI for forward primers and EcoRI for reverse primer) to facilitate cloning of the amplicon.

PCR amplification mixes (100 μl) contained 0.5 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 × PCR buffer, 2.5 U of Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene), 0.25 μM each primer, and 100 ng of purified M. elsdenii DNA. Thermal cycler conditions were 95°C for 2 min, followed by 36 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, reannealing at 50°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. The last cycle was extended an additional 10 min at 72°C. The amplicons were purified by ethanol precipitation, double digested with BamHI and EcoRI, deproteinized by phenol-CHCl3 extraction, purified by ethanol precipitation and ultrafiltration (Nanosep 10K filters; Pall Life Sciences), and ligated into plasmid pZero-2 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) that had been linearized by digestion with both enzymes. Plasmid pZero-2 contains both a kanamycin resistance gene and a lacZα-ccdB fusion enabling positive selection (CcdB protein toxicity) against plasmids not containing insert DNA. A 2:1 (insert-to-vector) molar ratio of DNA ends was used. E. coli Top10 cells were electrotransformed with recombinant plasmids, and survivors were plated onto agar medium containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chlortetracycline (8 μg/ml). The instructions of the plasmid manufacturer for DNA preparation, ligation, electrotransformation, and selection of bacterial transformants were followed closely.

Plasmids from tetracycline-resistant E. coli strains were purified with anion exchange columns (plasmid midi kit; Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The M. elsdenii tet gene inserts on the plasmids were sequenced by automated PCR cycle sequencing techniques (22) at the Iowa State University Nucleic Acid Facility.

PCR assays for M. elsdenii mosaic tet genes.

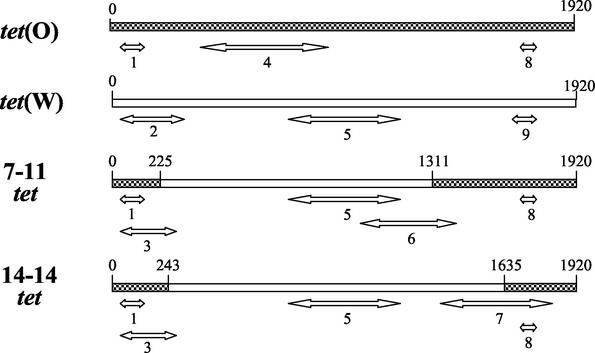

To detect tet mosaic genes in M. elsdenii strains, nine PCR assays were designed to amplify specific regions along the lengths of tet(O), tet(W), 7-11 tet, and 14-14 tet (see Table 1, Fig. 4). PCR assay conditions were the same as described above for identifying tet gene classes, with 30 cycles and an annealing temperature of 60°C.

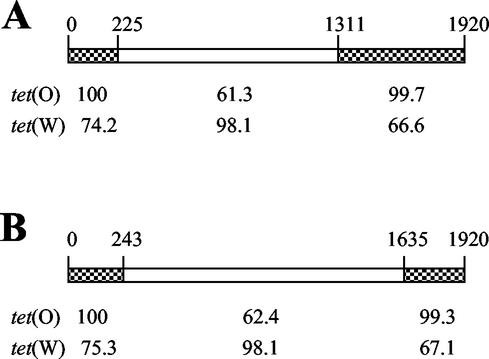

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of nine PCR amplicons differentiating tet(O), tet(W), and the mosaic tet genes from strains 7-11 and 14-14 (Table 1). Double-headed arrows indicate amplified regions of the target gene. PCR amplicons identifying specific genes are: product 4, tet(O); products 2 and 9, tet(W); product 6, 7-11 mosaic tet; product 7, 14-14 mosaic tet.

Statistical analysis.

Viable bacterial counts in swine cecal samples were normalized by logarithmic transformation and statistically analyzed with a mixed-models analysis of variance for the effect both of animal origin and chlortetracycline concentration in the culture medium. Pooled estimates of the experimental error from the analysis were used to make inferences. P values of ≤0.01 were considered significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 2-9, 4-13, and 7-11 16S rDNA sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AY196917, AY196918, and AY196919, respectively. The M. elsdenii strain 7-11 and 14-14 tet sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AY196921 and AY196920, respectively.

RESULTS

PCR assays for tet gene classes.

To detect and identify tetracycline resistance genes in swine intestinal anaerobes, previously reported PCR assays (6) for gene classes tet(M), tet(O), tet(Q), tet(S), and tet(W), encoding ribosomal protection proteins, were adopted. PCR assays for tet gene classes tet(A), tet(B), tet(C), tet(D), tet(E), tet(G), tet(H), tet(K), and tet(L), encoding efflux proteins, were not available at the beginning of this research and were developed as part of this study (Table 1). All PCR assays were validated with strains carrying known tet genes. Every validation strain gave a single amplicon in the PCR assay targeting the gene it carried and a negative reaction in all other tet PCR assays. Amplicon sizes were consistent with published results, in the case of tet ribosomal protection genes (6), or with expected sizes, in the case of tet efflux protein genes. Based on these results, the assays were considered reliable for initial, presumptive identification of tet genes in swine intestinal bacteria.

Viable bacterial counts of swine cecal samples.

Bacteria able to grow on RTC agar medium without chlortetracycline were detected at average population densities of 1.5 × 1010 to 2.8 × 1010 CFU/g (wet weight) of cecal contents and 1.2 × 107 to 1.7 × 107 CFU/cm2 of cecal tissues of swine from the two farms in this study (Table 2). These numbers compare reasonably with previous estimates of swine bacterial populations (2.4 × 1010 CFU/g of cecal contents and 2.7 × 107 CFU/cm2 of cecal tissues) as determined by Allison et al. with CCA agar medium and anaerobic roll tube methods (4).

TABLE 2.

Total and tetracycline-insensitive bacterial population levels in swine cecal contents and cecal tissue homogenates

| Sample | Chlortetra- cycline concn (μg/ml) | No. of viable bacteriaa ± SEM

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Farm A | Farm B | ||

| Cecal contents | 0 | 10.44 ± 0.065 | 10.18 ± 0.071 |

| 4 | 10.39 ± 0.066 | 10.18 ± 0.092 | |

| 16 | 10.17 ± 0.067A | 10.13 ± 0.083 | |

| 64 | 9.62 ± 0.093A,B | 10.12 ± 0.095B | |

| 128 | ND | 10.07 ± 0.041 | |

| 256 | 7.68 ± 0.140A,B | 9.68 ± 0.084A,B | |

| Cecal tissues | 0 | 7.24 ± 0.060 | 7.07 ± 0.132 |

| 4 | 7.25 ± 0.107 | 7.08 ± 0.143 | |

| 16 | 6.91 ± 0.163 | 7.11 ± 0.109 | |

| 64 | 6.38 ± 0.118A,B | 7.07 ± 0.112B | |

| 128 | ND | 6.80 ± 0.085 | |

| 256 | 5.07 ± 0.373A,B | 6.40 ± 0.014A,B | |

Values are average log10 bacterial counts for animals from each farm for cecal contents and cecal tissues. Farm A, seven swine fed a diet without tetracycline (or other antibiotics). Farm B, six swine fed a diet containing 400 g of chlortetracycline/ton. A, values are significantly (P ≤ 0.01) different from values of samples from the same farm and cultured on medium without antibiotic. B, values are significantly different between farms at the same antibiotic concentration. ND, not determined.

Except for cecal contents from animals at farm A, bacterial CFU in the samples were unaffected by 4 or 16 μg of chlortetracycline/ml (Table 2). At higher chlortetracycline concentrations (64 to 256 μg/ml), cecal bacterial populations insensitive to chlortetracycline were significantly (3- to 100-fold) greater in chlortetracycline-fed animals than in animals not fed the antibiotic. Nevertheless, in animals on either diet, substantial numbers of bacteria were insensitive to medium with 256 μg of chlortetracycline/ml, the highest concentration tested. These results indicate that many commensal anaerobes in the swine intestine are either resistant or insensitive to chlortetracycline.

Eighty-four colonies were randomly selected from RTC plates containing 64 or 256 μg of chlortetracycline/ml, subcultured once by single-colony transfer, examined for cell morphology and gram stain reaction, and placed into frozen stock. The 84 strains were diverse, based on both cell and colony morphology. Based on V3 16S rDNA sequence similarities with GenBank sequences, they are related to known and unknown species of Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Eubacterium, Ruminococcus, Prevotella, and Megasphaera. Some are uncharacterized bacterial genera.

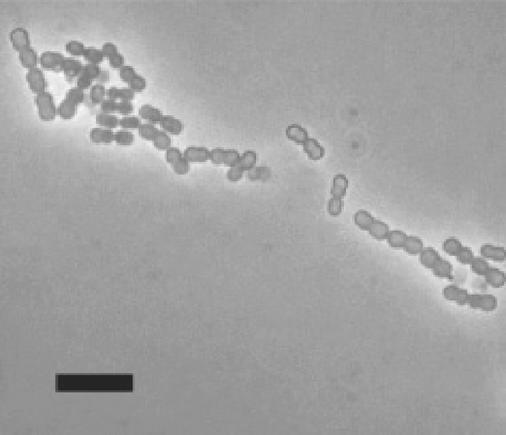

Eight swine strains showed a distinctive cell morphology, cocci with large cell diameters (Fig. 1). The strains were isolated from cecal contents and tissues of seven different pigs (Table 3). Based on the dilutions of cecal contents or tissue homogenates from which they were obtained, the population levels of these cocci were conservatively estimated to be 107 CFU/g of cecal contents and 106 CFU/cm2 of cecal tissues. In that they had a distinctive morphology, were among the more numerous tetracycline-insensitive bacteria, and were potentially useful commensal “model bacteria” in future studies, the strains were again cloned by colony subculture and investigated further.

FIG. 1.

Phase contrast photomicrograph of M. elsdenii 7-11 cells. Wet mount preparation. Marker bar, 10 μm.

Identification of tetracycline-resistant cocci as M. elsdenii strains.

The eight selected strains grew in RTC broth, predominantly in cell pairs, although chains of four to eight cells were common. Strain 7-11 cells (Fig. 1) had a representative morphology and measured 1.2 to 1.5 μm in diameter. Cells of some strains clumped, forming large cell aggregates which settled out of broth cultures. Cells from cultures in the exponential growth phase were gram reaction negative to variable. Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis, used as controls, consistently gave the expected gram staining reactions.

Within the amplified V3 variable region of their rrs genes, the eight strains showed 96.8 to 100% nucleotide similarity with each other. The Sequence Match version 2.7 program was used to search RDPII for matching sequences. Bacterial species with the most similar V3 sequences formed the Veillonella parvula subgroup of the Sporomusa group of gram-positive bacteria. The closest related species in the database was Megasphaera elsdenii strain B159 (GenBank accession number M26493). The V3 sequences of the eight strains showed 98.2 to 99.4% sequence identity with the M. elsdenii type strain LC-1T (Table 3).

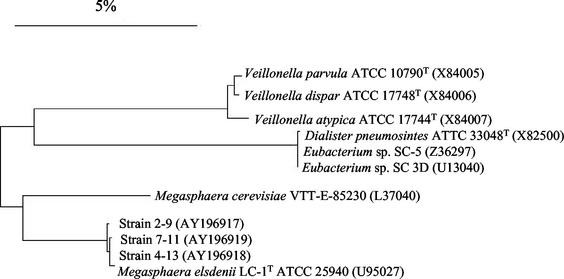

Phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2) of nearly complete rrs gene sequences (1,475 bp) of strains 7-11, 4-13, 2-9, M. elsdenii LC-1T, and species within the Veillonella parvula subgroup indicated the uncharacterized strains were closely related to M. elsdenii LC-1T (99.3 to 99.6% sequence similarity). The nearest relative is Megasphaera cerevisiae (93.8 to 94% sequence similarity), which was isolated from spoiled beer (21) and not considered an intestinal inhabitant.

FIG. 2.

Neighbor-joining dendrogram depicting phylogenetic relationships based on nearly complete 16S rDNA sequences among swine isolates 2-9, 7-11, and 4-13 and selected members of the Veillonella parvula subgroup. GenBank accession numbers are in parentheses. Nucleotide differences are determined by the sum of the horizontal lines connecting the organisms. The scale bar represents a 5% difference in nucleotide sequence.

A significant physiological trait of M. elsdenii is the ability to use lactate as a carbon and energy source (15, 34, 47). All eight swine strains and three control (ruminant) M. elsdenii strains grew rapidly in PY broth containing 1% lactate (Table 3). The strains reached maximum population levels (final culture OD620 = 1.4 to 1.85, 18-mm path length) within 10 to 12 h after inoculation (initial cell densities = 2 × 107 CFU/ml). Growth of all strains on lactate was better than on glucose (20 to 23 h to attain maximum OD620 of 1.0 to 1.4 in PY broth containing 1% glucose).

On the basis of phylogenetic, morphological, and physiological properties, we concluded that the eight strains of large cocci were M. elsdenii strains.

Antibiotic MIC determinations.

MICs of tetracycline compounds for the eight M. elsdenii swine isolates ranged from 64 to greater than 256 μg/ml (Table 3). These values were 16- to 64-fold higher than the corresponding MICs for ruminant M. elsdenii strains LC-1T, B159, and T81. Tetracycline MICs for Bacteroides reference strains agreed with the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) values (41). Based on these results, the swine strains were considered tetracycline resistant and the ruminant strains tetracycline sensitive.

PCR assays for tet gene classes.

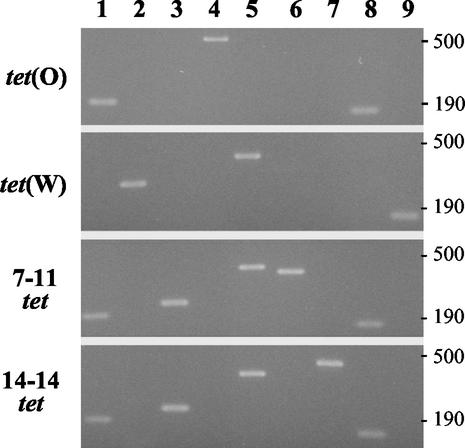

Every tetracycline-resistant M. elsdenii strain (Table 3) gave a positive reaction in a PCR assay to detect the tet(O) class of tetracycline resistance genes (strains 7-11 and 14-14, depicted as product 1 in Fig. 5, lane 1). Tetracycline-sensitive strains LC-1T, B159, and T81 were negative. None of the M. elsdenii strains, tetracycline resistant or sensitive, gave a positive reaction for the other tet class genes.

FIG. 5.

PCR assays to identify tet(O), tet(W), and mosaic tet genes of strains 7-11 and 14-14. Size markers (in base pairs) are given at the right of the figure. Lane numbers 1 to 9 correspond to PCR products 1 to 9 depicted schematically in Fig. 4.

The amplicons of the tet(O) PCR of M. elsdenii strains 7-11 and 14-14 were purified and sequenced. Between the primer regions, both sequences (129 bp) were identical to each other and to a comparable region of the tet(O) gene of Campylobacter jejuni (GenBank accession number M18896).

Cloning M. elsdenii 7-11 and 14-14 tetracycline resistance genes.

The PCR results suggested that the M. elsdenii tetracycline resistance determinant belonged to the tet(O) class. To confirm this conclusion, the tetracycline resistance determinants of strains 7-11 and 14-14 were amplified and cloned into E. coli. Since M. elsdenii gene expression has not been investigated, two sets of PCR primers were used to amplify and clone the 7-11 tet. Str primers were designed to enable expression of tet from a native M. elsdenii promoter. Fus primers were designed to enable expression as a fusion protein from the lacZ gene promoter on pZero-2. Recombinant E. coli strains containing either 7-11 tet amplicon had increased chlortetracycline and tetracycline MICs compared to the parent E. coli strain Top10 and control strains (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Tetracycline MICs for E. coli strains containing M. elsdenii tetracycline resistance determinants

| Strain | Description | M. elsdenii tet gene | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tet | Ctc | |||

| ATCC 25922 | TcS reference | None | 1-2 | 4-8 |

| TOP10 | Cloning parent strain | None | 2 | 8 |

| B-1 | TOP10 containing pZErO-2 with fla insertb | None | 2 | 8 |

| STR7-11 | TOP10 containing pZero-2 with 7-11 amplicon | 7-11 Str amplicon | 32 | 64-128 |

| FUS7-11 | TOP10 containing pZero-2 with 7-11 amplicon | 7-11 Fus amplicon | 32 | 128 |

| STR14-14 | TOP10 containing pZero-2 with 14-14 amplicon | 14-14 Str amplicon | 64 | 128 |

Expressed per milliliter of Mueller-Hinton agar. Results of at least two determinations. Tet, tetracycline; Ctc, chlortetracycline.

Strain B-1 containing plasmid pZero-2 with a Brachyspira hyodysenteriae fla insert was used as a control since pZero-2 plasmid without insert is lethal for E. coli TOP10 cells.

Considering that the MICs of the E. coli strains containing either 7-11 amplicon were comparable, only one PCR amplicon version, made from Str primers, was cloned from strain 14-14. The M. elsdenii 14-14 gene also conferred tetracycline resistance on E. coli (Table 4).

Mosaic nature of M. elsdenii tet.

Three clones originating from independent amplifications of the 7-11 tet gene were sequenced and found to be identical. Two independent 14-14 tet sequences were identical to each other. Surprisingly, in view of the PCR results detecting tet(O), the complete nucleotide sequences of the M. elsdenii 7-11 and 14-14 tet genes were only 78% and 72.5% similar to the C. jejuni tet(O), respectively.

Sequence comparisons with various tet classes revealed that the 7-11 and 14-14 genes had specific regions matching two different tet classes, tet(O) of C. jejuni and tet(W) of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens (Fig. 3). The middle portions of the genes had 98.1% identical nucleotide sequences with tet(W). The beginning and end regions of the genes, however, showed 99.3 to 100% sequence similarity with tet(O) of C. jejuni. Additionally, the nucleotide sequence (129 bases) upstream of the M. elsdenii 7-11 tet gene was 98.4% identical to the upstream region of C. jejuni tet(O) (not shown). These results indicate that the M. elsdenii 7-11 and 14-14 tet determinants are mosaic genes produced from a double-crossover recombination of tet(O) and tet(W). The genes differed in crossover sites (O-W or W-O) (Fig. 3). In the initial PCR assays, primers specific for tet(O) amplified a tet(O) region of the M. elsdenii mosaic genes (depicted as product 1 in Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of tet genes from M. elsdenii strain 7-11 (A) and strain 14-14 (B). Checkered regions indicate high sequence similarity with C. jejuni tet(O) (M18896), and open regions indicate high sequence similarity with B. fibrisolvens tet(W) (AJ222769). Nucleotide base positions are indicated above each gene. Percent sequence similarities are indicated below each gene.

PCR assays for M. elsdenii mosaic tet genes.

PCR assays were developed to detect and differentiate tet(O), tet(W), and the 7-11 and 14-14 tet mosaic genes (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). The six other tetracycline-resistant M. elsdenii strains were tested in the PCR assays. Strain 2-9 gave PCR results identical to those of strain 7-11 (Fig. 5). The other five strains, 4-13, 7-12, 15-5, 19-3, and 20-11, had PCR results similar to those of 14-14 (Fig. 5). These results indicate that there at least two distinct tetracycline resistance genotypes among swine isolates of M. elsdenii.

DISCUSSION

Eight of 84 strains of swine intestinal anaerobes growing in medium containing high levels of chlortetracycline were identified as strains of M. elsdenii. The tetracycline-resistant strains were isolated from the ceca of swine regardless of a history of tetracycline in their diet. Two tetracycline resistance genotypes, represented by strains 7-11 and 14-14, were detected by PCR assays in the swine isolates of M. elsdenii. These tet genes were absent from tetracycline-sensitive strains, and PCR copies of the genes conferred tetracycline resistance on recombinant E. coli strains. More recently, a tet gene was cloned directly from M. elsdenii 7-11 genomic DNA in our laboratory and was identical in sequence to the 7-11 tet amplicon cloned in these investigations.

M. elsdenii, originally called Peptostreptococcus elsdenii (50), has been detected in intestinal contents and feces of ruminants (20, 24, 26), swine (1, 23, 32, 58), and humans (56, 59). Results from these studies suggest that M. elsdenii might colonize intestinal mucosal surfaces (Table 3), a habitat where microbial biofilms are likely sites of genetic and physiological exchanges.

Although M. elsdenii strains have been associated with disease (11, 18, 56), the species is better known as a commensal or mutualist organism whose ecological niche lies at the intersection of various metabolic pathways of the rumen and lower bowel ecosystems (3, 38, 52). Most noteworthy, M. elsdenii converts lactate to propionate, a glucogenic metabolite for the host animal (14, 15, 31). Depending on the animal diet, M. elsdenii ferments up to 60 to 80% of the lactate produced in the rumen (15), a metabolic capacity that makes it attractive as a probiotic culture to prevent acidosis caused by lactate-producing bacteria in cattle (30, 47). Our working hypothesis is that physiological interactions of M. elsdenii with other species might predispose genetic exchanges among these species.

Ruminant M. elsdenii strains have been analyzed previously for tetracycline sensitivity (19, 36). Unfortunately, the methods for assessing sensitivity did not follow the protocols used in these investigations, making MIC comparisons impossible and underscoring the importance of standard assays (41).

The M. elsdenii tet determinants are mosaic genes formed by recombination of tet(O) and tet(W) class genes. Mosaic penicillin resistance genes are present in Streptococcus pneumoniae (25) and Neisseria species (55). Mosaic tet(M) genes in Neisseria, Enterococcus, Ureaplasma, and Streptococcus species are the products of recombination between tet(M) genes from Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae (46). Functional gene hybrids of two different tet classes [tet(A)-tet(C)] have been genetically created in the laboratory (51). To our knowledge, the M. elsdenii resistance determinants are unique in being the first natural examples of mosaic genes formed between two distinct classes of tetracycline resistance genes, that is, genes separated by 36% nucleotide sequence divergence.

An intriguing mystery surrounds the origin of the M. elsdenii mosaic tet determinants. Does recombination between tet(O) and tet(W) occur within M. elsdenii cells, or do mosaic genes originate from other bacterial genera?

Although hybrid tet(O)-tet(W) genes have not been reported, tet(W) genes are present in diverse genera from gastrointestinal environments, e.g., Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, Selenomonas ruminantium, Mitsuokella multiacidus, Fusobacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium longum, Clostridium-like strain K-10, and Arcanobacterium pyogenes (8, 9, 37, 54). The tet(O) gene is present in various gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, notably gram-positive cocci (13, 60), and in intestinal bacteria such as Campylobacter spp. (13) and B. fibrisolvens (8). B. fibrisolvens strains contain both tet(W) and tet(O) in the same bacterium (8). There is evidence of intergeneric transfers of tet determinants among intestinal bacteria (8, 16, 37, 54). The PCR assays developed in these studies should be useful for determining whether additional M. elsdenii strains contain more than one tet gene class and for examining other intestinal bacteria for the mosaic genes.

The existence of interclass mosaic tet genes in M. elsdenii has practical implications for investigators of tetracycline resistance. First, assays targeting specific regions of tet genes can be deceiving. Based on the results of a positive PCR assay limited to a specific region of tet(O) (6), the M. elsdenii tet determinant was initially considered to belong to class tet(O). Furthermore, we speculate that DNA hybridization probes for tet(W) could misidentify the mosaic genes due to the large portions of the genes showing high sequence homology with tet(W). For these reasons, the identification of tet gene classes in (unstudied) bacteria in pure culture should be based on complete sequencing or on PCR assays targeting multiple regions of the gene. Future investigations of tet gene ecology in microbially complex environments (5, 6, 12) should consider the impact of mosaic tet genes on study results.

Second, the current cutoff for classifying tet genes is >80% amino acid identity of the encoded proteins (33). This nomenclature guideline was based on comparisons of known tet genes, which, unlike the mosaic tet, vary in sequence over their entire lengths. On the basis of this criterion, both the M. elsdenii 7-11 and 14-14 genes should be classified as tet(W) alleles because the putative Tet proteins show 89.1% and 91.9% sequence identity, respectively, with B. fibrisolvens tet(W).

In our view, the classification of the M. elsdenii mosaic genes as tet(W) neither reflects the evolutionary background nor conveys the unique recombinant nature of the genes. It is also confusing for practical applications, because the M. elsdenii genes are clearly differentiated from tet(W) genes. For these reasons, we suggest that the genes not be named at this time. We fully support a uniform nomenclature for antibiotic resistance genes and suggest that future classification guidelines address mosaic tet genes.

The commensalistic microbiota of animals and humans has been proposed as a reservoir for the expansion, dissemination, and preservation of antibiotic resistance determinants. The existence of mosaic genes in M. elsdenii suggests that the normal intestinal microbes may serve not only as a reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes but also as a proving ground for the evolution of those genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stuart Levy for advice about naming tet genes. The insightful comments about tet classification and useful information about tetracycline resistance provided by Marilyn Roberts are both highly regarded and appreciated. John Bannantine and Steve Carlson provided comprehensive manuscript reviews, for which we are grateful. We acknowledge the statistical analysis support of Harold Ridpath. We thank the suppliers of tet class validation strains (Table 1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aalbaek, B. 1972. Gram-negative anaerobes in the intestinal flora of pigs. Acta Vet. Scand. 13:228-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics: Working Group on Antibiotic Resistance in Commensal Bacteria. 1998. ROAR position paper: commensal bacteria—an important reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes? Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics, Boston, Mass.

- 3.Allison, M. J. 1978. production of branched-chain volatile fatty acids by certain anaerobic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 35:872-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allison, M. J., I. M. Robinson, J. A. Bucklin, and G. D. Booth. 1979. Comparison of bacterial populations of the pig cecum and colon based upon enumeration with specific energy sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 37:1142-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aminov, R. I., J. C. Chee-Sanford, N. Garrigues, B. Teferedegne, I. J. Krapac, B. A. White, and R. I. Mackie. 2002. Development, validation, and application of PCR primers for detection of tetracycline efflux genes of gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1786-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aminov, R. I., N. Garrigues-Jeanjean, and R. I. Mackie. 2001. Molecular ecology of tetracycline resistance: development and validation of primers for detection of tetracycline resistance genes encoding ribosomal protection proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:22-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. 1969. 5.2.02 AOAC official method 968.49: chlortetracycline in feeds. J. AOAC 51:750. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbosa, T. M., K. P. Scott, and H. J. Flint. 1999. Evidence for recent intergeneric transfer of a new tetracycline resistance gene, tet(W), isolated from Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, and the occurrence of tet(O) in ruminal bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 1:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billington, S. J., J. G. Songer, and B. H. Jost. 2002. Widespread distribution of a tet(W) determinant among of tetracycline-resistant Isolates of the animal pathogen Arcanobacterium pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1281-1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Both, B., G. Krupp, and E. Stackebrandt. 1991. Direct sequencing of double-stranded polymerase chain reaction-amplified 16S rDNA. Anal. Biochem. 199:216-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brancaccio, M., and G. G. Legendre. 1979. Megasphaera elsdenii endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 10:72-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chee-Sanford, J. C., R. I. Aminov, I. J. Krapac, N. Garrigues-Jeanjean, and R. I. Mackie. 2001. Occurrence and diversity of tetracycline resistance genes in lagoons and groundwater underlying two swine production facilities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1494-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chopra, I., and M. Roberts. 2001. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:232-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Counotte, G. H. M., and R. A. Prins. 1981. Regulation of lactate metabolism in the rumen. Vet. Res. Commun. 5:101-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Counotte, G. H. M., R. A. Prins, R. H. A. M. Janssen, and M. J. A. deBie. 1981. Role of Megasphaera elsdenii in the fermentation of dl-[2-13C]lactate in the rumen of dairy cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 42:649-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Courvalin, P. 1994. Transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1447-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dewey, C. E., B. D. Cox, B. E. Straw, E. J. Bush, and S. Hurd. 1999. Use of antimicrobials in swine feeds in the United States. Swine Health Prod. 7:19-25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duran, S. P., J. V. Manzano, R. C. Valera, and S. V. Machota. 1990. Obligately anaerobic bacterial species isolated from foot-rot lesions in goats. Br. Vet. J. 146:551-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.el Akkad, I., and P. N. Hobson. 1966. Effect of antibiotics on some rumen and intestinal bacteria. Nature 209:1046-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsden, S. R., B. E. Volcani, F. M. C. Gilchrist, and D. Lewis. 1956. Properties of a fatty acid forming organism isolated from the rumen of sheep. J. Bacteriol. 72:681-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelmann, U., and N. Weiss. 1985. Megasphaera cerevisiae sp. nov., a new gram-negative obligately anaerobic coccus isolated from spoiled beer. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 6:287-290. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frothingham, R., H. G. Hills, and K. H. Wilson. 1994. Extensive DNA sequence conservation throughout the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1639-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giesecke, D., S. Wiesmayr, and M. Ledinek. 1970. Peptostreptococcus elsdenii from the caecum of pigs. J. Gen. Microbiol. 64:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez, J., R. E. Davis, I. L. Lindahl, and E. J. Warwick. 1959. Bacterial changes in the rumen during the onset of feed-lot bloat of cattle and characteristics of Peptostreptococcus elsdenii n. sp. Appl. Microbiol. 7:16-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakenbeck, R. 1998. Mosaic genes and their role in penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Electrophoresis 19:597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobson, P. N., S. O. Mann, and A. E. Oxford. 1958. Some studies on the occurrence and properties of a large gram-negative coccus from the rumen. J. Gen. Microbiol. 19:462-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holdeman, L. V., and W. E. C. Moore. 1975. Anaerobe laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Anaerobe Laboratory, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg.

- 28.Hungate, R. E. 1969. A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes, p. 117-132. In J. R. Norris and D. W. Ribbons (ed.), Methods in microbiology, vol. 3B. Academic Press Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 29.Kehrenberg, C., and S. Schwarz. 2001. Molecular analysis of tetracycline resistance in Pasteurella aerogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2885-2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kung, L., Jr., and A. O. Hession. 1995. Preventing in vitro lactate accumulation in ruminal fermentations by inoculation with Megasphaera elsdenii. J. Anim. Sci. 73:250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ladd, J. N., and D. J. Walker. 1959. The fermentation of lactate and acrylate by the rumen microorganism LC. Biochem. J. 71:364-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leser, T. D., J. Z. Amenuvor, T. K. Jensen, R. H. Lindecrona, M. Boye, and K. Moller. 2002. Culture-independent analysis of gut bacteria: the pig gastrointestinal tract microbiota revisited. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:673-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy, S. B., L. M. McMurry, T. M. Barbosa, V. Burdett, P. Courvalin, W. Hillen, M. C. Roberts, J. I. Rood, and D. E. Taylor. 1999. Nomenclature for new tetracycline resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1523-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackie, R. I., F. M. C. Gilchrist, and S. Heath. 1984. An in vivo study of ruminal microorganisms influencing lactate turnover and its contribution to volatile fatty acid production. J. Agric. Sci. 103:37-51. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maidak, B. L., J. R. Cole, T. G. Lilburn, C. T. Parker, Jr., P. R. Saxman, R. J. Farris, G. M. Garrity, G. J. Olsen, T. M. Schmidt, and J. M. Tiedje. 2001. The RDP-II (Ribosomal Database Project). Nucleic Acids Res. 29:173-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marounek, M., K. Fliegrova, and S. Bartos. 1989. Metabolism and some characteristics of ruminal strains of Megasphaera elsdenii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:1570-1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melville, C. M., K. P. Scott, D. K. Mercer, and H. J. Flint. 2001. Novel tetracycline resistance gene, tet(32), in the Clostridium-related human colonic anaerobe K10 and its transmission in vitro to the rumen anaerobe Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3246-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miura, H., M. Horiguchi, and T. Matsumoto. 1980. Nutritional interdependence among rumen bacteria Bacteroides amylophilus, Megasphaera elsdenii, and Ruminococcus albus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 40:294-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muyzer, G., E. C. de Waal, and A. G. Uitterlinden. 1993. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:695-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Academy of Sciences Committee on Drug Use in Feed Animals. 1999. Food-animal production practices and drug use, p. 27-68. In The use of drugs in food animals: benefits and risks. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

- 41.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria; approved standard, 4th ed., vol. 17, no. 22. (NCCLS document M11-A4.) National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 42.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1999. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals; approved standard, vol. 19, no. 11. (NCCLS document M31-A.) National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 43.Nelson, M. L. 2001. The chemistry and cellular biology of the tetracyclines, p.3-63. In M. Nelson, W. Hillen, and R. A. Greenwald (ed.), Tetracyclines in biology, chemistry, and medicine. Birkhauser Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 44.Ng, L. K., I. Martin, M. Alfa, and M. Mulvey. 2001. Multiplex PCR for the detection of tetracycline-resistant genes. Mol. Cell. Probes 15:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nonaka, L., and S. Suzuki. 2002. New Mg2+-dependent oxytetracycline resistance determinant tet 34 in Vibrio isolates from marine fish intestinal contents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1550-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oggioni, M. R., C. G. Dowson, J. M. Smith, R. Provvedi, and G. Pozzi. 1996. The tetracycline resistance gene tet(M) exhibits mosaic structure. Plasmid 35:156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ouwerkerk, D., A. V. Klieve, and R. J. Forster. 2002. Enumeration of Megasphaera elsdenii in rumen contents by real-time Taq nuclease assay. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:753-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts, M. C., and B. J. Moncla. 1988. Tetracycline resistance and TetM in oral anaerobic bacteria and Neisseria perflava-N. sicca. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1271-1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberts, M. C., Y. Pang, D. E. Riley, S. L. Hillier, R. C. Berger, and J. N. Krieger. 1993. Detection of Tet M and Tet O tetracycline resistance genes by polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Cell. Probes 7:387-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogosa, M. 1971. Transfer of Peptostreptococcus elsdenii Gutierrez et al. to a new genus, Megasphaera [M. elsdenii (Gutierrez et al.) comb. nov.]. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 21:187-189. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubin, R. A., and S. B. Levy. 1990. Interdomain hybrid Tet proteins confer tetracycline resistance only when they are derived from closely related members of the tet gene family. J. Bacteriol. 172:2303-2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russell, J. B., M. A. Cotta, and D. B. Dombrowski. 1981. Rumen bacterial competition in continuous cultures: Streptococcus bovis versus Megasphaera elsdenii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:1394-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook, J., and D. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 54.Scott, K. P., C. M. Melville, T. M. Barbosa, and H. J. Flint. 2000. Occurrence of the new tetracycline resistance gene tet(W) in bacteria from the human gut. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:775-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spratt, B. G., Q. Y. Zhang, D. M. Jones, A. Hutchison, J. A. Brannigan, and C. G. Dowson. 1989. Recruitment of a penicillin-binding protein gene from Neisseria flavescens during the emergence of penicillin resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:8988-8992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugihara, P. T., V. L. Sutter, H. R. Attebery, K. S. Bricknell, and S. M. Finegold. 1974. Isolation of Acidaminococcus fermentans and Megasphaera elsdenii from normal human feces. Appl. Microbiol. 27:274-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teo, J. W. P., T. M. C. Tan, and C. L. Poh. 2002. Genetic determinants of tetracycline resistance in Vibrio harveyi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1038-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vervaeke, I. J., and P. F. Van Assche. 1975. Occurrence of Megasphaera elsdenii in faecal samples of young pigs. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Hyg. I Abt. Orig. A 231:145-152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Werner, H. 1973. Megasphaera elsdenii—a normal inhabitant of human large intestine. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Hyg. I Abt. Orig. A 223:343-347. (In German.) [PubMed]

- 60.Zilhao, R., B. Papadopoulou, and P. Courvalin. 1988. Occurrence of the Campylobacter resistance gene tet(O) in Enterococcus and Streptococcus spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1793-1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]