Abstract

In this study, we determined the genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated in Norway from 1999 to 2001. The results were compared to those for strains isolated from 1994 to 1998. A total of 818 patients were diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) during the last 3-year period. Of these cases, 576 (70%) were verified by culturing, and strains from 551 patients (96%) were analyzed by the IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method. We excluded 13 strains (2.4%) from the analyses, since they were found to represent false-positive samples. A total of 67 strains (12%) that carried fewer than five copies of IS6110 were analyzed by spoligotyping. The strains were from 157 patients (29%) of Norwegian origin and 381 patients (71%) of foreign origin. The rate of diversity among all of the strains was 90%, while in 1994 to 1998 it was 87%. Clusters were assumed to have arisen from recent transmission; the degree of such transmission was 10% in 1999 to 2001, while for the whole 8-year period (1994 to 2001), it was 11%. Of the 109 patients diagnosed as being part of a cluster in 1999 to 2001, 89 were infected with a strain that carried more than four copies of IS6110. Among these 89 patients, 52 (58%) were infected with a strain that had already been identified in 1994 to 1998. The results indicated that most cases of TB in Norway were due to the import of new strains rather than to transmission within the country. This finding demonstrates that screening of immigrants for TB upon arrival in Norway needs to be improved. Outbreaks, however, were caused mainly by strains that have been circulating in Norway for many years.

Globally, the number of tuberculosis (TB) cases is currently increasing at 2% per year (8). Programs to keep TB from rising in low-incidence countries are challenged by international traveling and immigration from high-burden countries (2-5, 14, 15, 18, 22). In Norway, patients with a foreign background contribute substantially to the TB incidence (4, 5, 11).

In recent years, DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis with IS6110 as a probe has given new insight into the nature of TB transmission. It has also become an indispensable tool for quality assurance of the processing and culturing of patient samples (1, 4, 5, 7, 9, 13-16, 18, 21, 22). Since 1994, IS6110 RFLP analysis has been performed on basically all strains of M. tuberculosis isolated in Norway (4, 5). However, isolates of M. tuberculosis that possess few copies of IS6110 do not generate sufficient polymorphisms to be readily distinguished by this technique. Another method, spoligotyping, involves the simultaneous detection of the presence or absence of 43 DNA spacer sequences and is superior to IS6110 RFLP analysis in discriminating isolates with fewer than five IS6110 copies (12, 13, 20). Spoligotyping is therefore generally used to analyze strains with fewer than five copies of IS6110 (12, 13, 18, 20) and has been performed on such strains isolated in Norway since 1999.

These methods have been used to demonstrate that transmission of and reinfection with M. tuberculosis are uncommon in low-incidence countries and that most patients suffer from endogenous reactivation (1, 4, 9, 10, 16, 22). This has also been the situation in Norway (4). The aims of the present study were to determine the genetic diversity of the population of M. tuberculosis isolates in patients in Norway from 1999 to 2001 and to detect the degree of clustering of M. tuberculosis isolates. We also wanted to compare these results to those for the M. tuberculosis population isolated in Norway from 1994 to 1998 (4) to monitor the development of the TB situation in this country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and cultures.

The study population comprised 96% of all patients in Norway from whom at least one sample found positive for M. tuberculosis by culturing was collected in 1999 to 2001. A total of 14 microbiological laboratories, servicing the entire nation, performed the isolation of M. tuberculosis from patient samples. Patient information was collected at the Division of Epidemiology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway (NIPH), and strains were collected at the Division of Infectious Disease Control, NIPH, which serves as a National Reference Laboratory for TB. In this period, a total of 576 strains of M. tuberculosis were recovered from different patients, and 552 of these strains were received at the NIPH and analyzed consecutively. Laboratory cross-contamination was suspected when two or more strains with identical fingerprint patterns were received from the same laboratory within 7 days and with no epidemiological data connecting the patients (7). The clinical presentation of the patients and additional laboratory data were considered to determine the most likely actual patient in each case (7). These strains were excluded from the analyses. The results of the present report were compared to those for 698 strains isolated from 697 patients in 1994 to 1998 (4).

The species identification of the strains was based on a 16S ribosomal DNA hybridization technique (AccuProbe; GenProbe Inc., San Diego, Calif.) and standard microbiological tests (nitrate reduction and niacin accumulation tests). In this article, first- and second-generation refugees or immigrants with foreign or Norwegian citizenship are called immigrants, and patients born in Norway to Norwegian parents are called ethnic Norwegians.

Molecular analyses of strains.

The analyses included IS6110 RFLP analysis for all strains as described previously (4, 13, 21) and spoligotyping for strains with fewer than five copies of IS6110 (12, 13, 20). A cluster of strains was defined as two or more strains which exhibited 100% identical RFLP patterns for strains with more than four copies of IS6110.

Strains with fewer than five copies of IS6110 also had to have identical spoligotypes to be considered identical. The strains from 1994 to 1998 that carried fewer than five copies of IS6110 had been analyzed by direct repeat (DR) RFLP analysis (4), and therefore the comparison of strains from 1994 to 1998 to those from 1999 to 2001 was restricted to those that carried more than four copies of IS6110. The IS6110 fingerprint patterns were compared by visual examination and computer-assisted analyses by use of GelCompar version 4.1 software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). To facilitate the comparison of the fingerprints, normalization was done by using the molecular weight standards on each gel. Similarity measures were calculated by using the Dice coefficient. Cluster analysis was performed by using the unweighted pair-group average method. The patterns obtained by spoligotyping were compared by visual examination and with computer assistance by sorting the results in an Excel sheet (Microsoft Excel 97; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Wash.).

The rate of diversity was calculated by dividing the number of different IS6110 RFLP patterns by the number of strains fingerprinted. The degree of recent transmission was calculated by dividing the numbers of strains in clusters minus one per cluster by the number of fingerprinted strains (19). The majority of the clustered strains and some orphan strains (among those isolated from 1999 to 2001) carried IS6110 RFLP patterns identical to those of strains that had been isolated before 1999. Therefore, the degree of clustering was calculated both with and without strains from 1994 to 1998.

RESULTS

A total of 818 patients were originally diagnosed with TB from 1999 to 2001. Of these cases, 576 (70%) were verified by culturing; 552 strains from 551 patients (96%) were analyzed. From one immigrant from Russia, however, repeated M. tuberculosis cultures gave inconclusive susceptibility results for isoniazid and rifampin, as well as both high- and low-intensity bands in IS6110 RFLP analysis. It was suspected that she was infected with two different strains of M. tuberculosis. At the NIPH, these strains were separated by subculturing of single colonies, and it was demonstrated that the patient was infected with one multidrug-resistant strain and one fully susceptible strain. One of the isolates carried 9 copies of IS6110, and the other carried 12 copies. The RFLP patterns had no similarity to each other and clearly represented those of two different strains (both unique IS6110 RFLP patterns in the Norwegian database).

Detection of laboratory cross-contamination.

Of the 552 strains, a total of 13 (2.4%) were likely to represent laboratory cross-contamination. Contamination was found in five laboratories and generally included only one false-positive culture; in one exception, seven cultures were contaminated by one isolate. The 13 strains were excluded from further analyses. None of the 13 patients had been treated for TB.

Patient origin and age.

After exclusion of the suspected laboratory cross-contaminants, 539 strains from 538 patients remained. A total of 157 (29%) of these patients were ethnic Norwegians, and 381 (71%) were first- or second-generation immigrants. The immigrants originated from Somalia (n = 143), Pakistan (n = 39), former Yugoslavia (n = 39), Ethiopia (n = 19), Vietnam (n = 17), Thailand (n = 11), former Soviet Union (n = 11), India (n = 10), and 33 other countries (n = 91). For one patient, the geographic origin was unknown, but based on his name, he was considered to be an immigrant. The age distribution of the patients was similar to that found in 1994 to 1998 (4). The patients were from 0 to 97 years old. The average age of patients of Norwegian background was 68.6 years (median age, 74 years), and that of patients of foreign background was 31.8 years (median age, 30 years).

DNA polymorphisms in M. tuberculosis strains.

The distribution and number of IS6110 copies in strains from patients of foreign and Norwegian backgrounds were similar to those found in 1994 to 1998 (4). It was more common to isolate high-copy-number strains and low-copy-number strains from immigrants than from ethnic Norwegians. A total of 67 strains carried fewer than five copies of IS6110, and these were analyzed by spoligotyping. Among these strains, we found six clusters comprising a total of 20 strains (Table 1). The largest cluster, based on spoligotyping, comprised eight strains with spoligotype 777777777413731 in the octadecimal code (6). This spoligotype was represented by strains from seven Somali immigrants and an ethnic Norwegian patient. They all carried one copy of IS6110. The remaining 47 strains had IS6110 patterns and spoligotypes that were unique in the Norwegian database, although the spoligotypes for some of these had been observed in other countries (18, 20).

TABLE 1.

Data on M. tuberculosis clusters based on spoligotyping of strains isolated in Norway in 1999 to 2001, geographic origins, patient ages

| Spoligotypea | Cluster sizeb | No. of IS6110 copies | Geographic origin(s) (age or age rangec) of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400037777613771 | 4 | 3 | Somalia (31 and 32), Pakistan (39), and Ethiopia (39) |

| 757777777413731 | 2 | 1 | Vietnam (58) and Zambia (36) |

| 777737774413771 | 2 | 2 | Norway (52 and 65) |

| 777777777413731 | 8 | 1 | Somalia (13-39 [7 patients]) and Norway (39 [1 patient]) |

| 777777777760731 | 2 | 1 | Ethiopia (both 16) |

| 777777777760771 | 2 | 1 | Norway (42) and Pakistan (20) |

Spoligotype designations are based on the nomenclature of Dale et al. (6)

Cluster size is number of patients with identical isolates.

Ages and age ranges are given in years.

Among the strains with more than four copies of IS6110, 383 (81%) carried unique fingerprints and 89 belonged to 49 clusters. Of these, strains from 37 patients grouped into 15 clusters carried RFLP patterns that had not been observed before 1999 (Table 2). Of these clusters, only three included strains from ethnic Norwegians. A total of 34 clusters included strains from patients diagnosed before 1999, and 18 of these strains had been isolated before 1997 (Table 2). Thus, among the clustered strains that carried more than four copies of IS6110, 58% had been identified in Norway previously. From 1994 to 1998, 12 of the outbreaks that were caused by a strain that carried more than four copies of IS6110 included more than two patients (4). Of these 12 strains, 8 were also isolated from 1999 to 2001, indicating that these outbreaks were still ongoing. From 1994 to 2001, five clusters included more than five patients; the IS6110 RFLP patterns of these strains are given in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Clustering of M. tuberculosis strains with more than four copies of IS6110 and isolated from patients in Norway

| No. of: | Cluster sizea at end of:

|

Geographic origin(s) (age or age range) of patients diagnosed inb:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS6110 copies | Isolates in 1999 to 2001 | Clusters in 1999 to 2001 | 1998 (yr of index case) | 2001 | 1994-1998 | 1999-2001 |

| 5 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 2 | — | Somalia (21 and 31) |

| 4 (1995) | 5 | Former Yugoslavia (24-46) | Former Yugoslavia (37) | |||

| 6 | 14 | 2 | 4 (1995) | 5 | Somalia (21-33) | Somalia (12) |

| 1 (1996) | 3 | Norway (85) | Former Yugoslavia (39) and Somalia (13) | |||

| 7 | 38 | 7 | 1 (1996) | 2 | Norway (76) | Former Yugoslavia (87) |

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Somalia (34) | Turkey (34) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Ethiopia (30) | Ethiopia (31) | |||

| 0 | 2 | — | Former Yugoslavia (1 and 27) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 4 | Norway (61) | Norway (31, 33, and 80) | |||

| 6 (1995) | 9 | Norway (44-83) | Norway (26, 47, and 75) | |||

| 1 (1995) | 2 | Norway (68) | Norway (74) | |||

| 8 | 44 | 8 | 1 (1998) | 2 | Norway (87) | Norway (87) |

| 1 (1997) | 2 | Pakistan (3) | Pakistan (51) | |||

| 0 | 3 | — | Former Yugoslavia (26, 28, and 41) | |||

| 1 (1994) | 2 | Somalia (27) | Former Yugoslavia (27) | |||

| 6 (1995) | 7 | Norway (33-66) | Norway (67) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Norway (86) | Norway (71) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Former Yugoslavia (24) | Former Yugoslavia (71) | |||

| 1 (1994) | 2 | Norway (44) | Norway (75) | |||

| 9 | 60 | 7 | 0 | 3 | — | Norway (72 and 83) and The Gambia (33) |

| 0 | 2 | — | Norway (79 and 82) | |||

| 1 (1995) | 2 | Former Yugoslavia (33) | Former Yugoslavia (29) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Norway (80) | Norway (59) | |||

| 0 | 3 | — | Somalia (21 and 22) and Ethiopia (35) | |||

| 3 (1997) | 4 | Somalia (19, 23, and 24) | Somalia (3) | |||

| 0 | 2 | — | Somalia (14 and 34) | |||

| 10 | 62 | 3 | 1 (1996) | 2 | Norway (65) | Norway (80) |

| 1 (1997) | 2 | Norway (54) | Somalia (26) | |||

| 1 (1996) | 2 | Norway (39) | Former Soviet Union (20) | |||

| 11 | 57 | 6 | 12 (1996) | 16 | Norway (36-86) | Norway (45-80) |

| 0 | 2 | — | The Philippines (35 and 39) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Norway (76) | Norway (73) | |||

| 0 | 5 | — | Somalia (3-21) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Somalia (14) | Angola (23) | |||

| 1 (1997) | 2 | Somalia (28) | Somalia (17) | |||

| 12 | 54 | 5 | 4 (1996) | 5 | Norway (39-50) | Norway (63) |

| 1 (1996) | 2 | Norway (52)c | Norway (43)c | |||

| 0 | 2 | — | Former Soviet Union (59) and Thailand (34) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 6 | Somalia (37) | Somalia (22-38) [4 patients]) and Democratic Republic of the Congo (9) | |||

| 1 (1998) | 3 | Somalia (34) | Tanzania (46) and Ethiopia (33) | |||

| 13 | 36 | 3 | 1 (1996) | 2 | Somalia (32) | Somalia (12) |

| 1 (1998) | 2 | Sudan (39) | Angola (23) | |||

| 0 | 2 | — | Somalia (11 and 35) | |||

| 14 | 38 | 3 | 0 | 2 | — | Somalia (18 and 31) |

| 0 | 2 | — | Somalia (29 and 36) | |||

| 1 (1995) | 2 | Somalia (26) | Somalia (37) | |||

| 15 | 24 | 2 | 0 | 2 | — | Somalia (17) and Norway (64) |

| 14 (1994) | 20 | Somalia (21-35 [11 patients]), Ethiopia (31 and 32), and Norway (1) | Somalia (2-48 [6 patients]) | |||

| 16 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 3 | — | Pakistan (21, 25, and 31) |

| 17 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| 19 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| 21 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

Cluster size is number of patients with identical isolates.

The non-Norwegian patients include first- and second-generation immigrants.

Eleven copies of IS6110 were identical to those found in an outbreak strain carrying 11 copies of IS6110 in 16 Norwegians. Ages and age ranges are given in years.

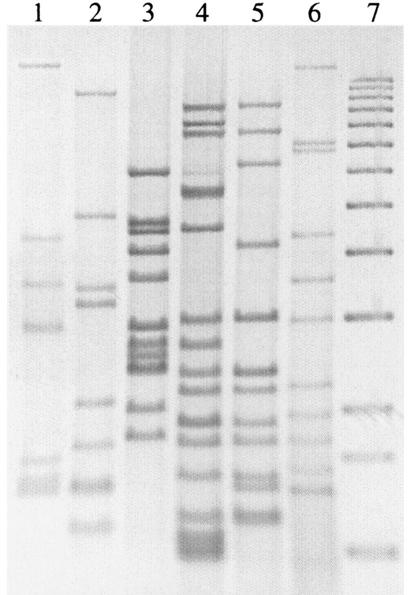

FIG. 1.

IS6110 RFLP patterns of M. tuberculosis strains representing clusters of more than five patients diagnosed in Norway from 1994 to 2001. Lane 1, strain isolated from 9 Norwegians (7 copies of IS6110; Table 2); lane 2, strain isolated from 7 Norwegians (8 copies of IS6110; Table 2); lane 3, strain isolated from 16 Norwegians (11 copies of IS6110; Table 2); lane 4, strain isolated from 17 Somalis, 2 Ethiopians, and 1 Norwegian (15 copies of IS6110; Table 2); lane 5, strain isolated from 5 Somalis and 1 Congolese (12 copies of IS6110; Table 2); lane 6, M. tuberculosis Mt14323; lane 7, molecular weight markers. From the top, the sizes of the fragments are 12,232, 11,198, 10,180, 9,162, 8,144, 7,126, 6,108, 5,090, 4,072, 3,054, 2,036, 1,635, and 1,018 bp.

The rate of diversity among all 539 strains isolated from 1999 to 2001 was 90%; the rate of diversity among the 698 strains analyzed from 1994 to 1998 was 87%. The degree of clustering for 1999 to 2001 was calculated to be 10%. A total of 30% of the patients from former Yugoslavia and from Somalia were infected with clustered strains. For the 8-year period (1994 to 2001), the degree of clustering among the patients infected with a strain that carried more than four copies of IS6110 was 11%.

It was uncommon to find ethnic Norwegians and immigrants in the same clusters. It was also uncommon to find immigrants of different geographic origins in the same clusters. From 1994 to 2001, nine clusters included both ethnic Norwegians and immigrants (Tables 1 and 2).

DISCUSSION

The population of M. tuberculosis analyzed in this study represents 96% of all bacteriologically verified cases and 67% of all TB cases reported in Norway from 1999 to 2001. The applied methods are internationally established and well suited to studying the epidemiology and transmission of M. tuberculosis (1, 4-7, 9, 12-22). Since IS6110 RFLP analysis had been performed on strains isolated in Norway since 1994, it was possible to compare the results from 1999 to 2001 for all strains that carried more than four copies of IS6110 to the results for strains from the previous 5-year period. Thus, the strains studied and the results obtained are representative for the population of M. tuberculosis in Norway. From 1994 to 1998, DR RFLP analysis was used as a secondary molecular marker for 81 strains that carried fewer than five copies of IS6110. For 1999 to 2001, however, the preferred method of spoligotyping was used to differentiate these strains. It was therefore difficult to compare the results found in 1994 to 1998 to those found in 1999 to 2001 for strains that carried fewer than five copies of IS6110. The study did enable us to define the magnitude of TB transmission in Norway and to identify the possible chains of transmission.

More than 70% of the patients diagnosed with TB in Norway in 1999 to 2001 had a foreign background, while the proportion in 1994 to 1998 was 53%. The genetic diversity of M. tuberculosis was slightly higher than that found in 1994 to 1998; thus, more new strains were identified than disappeared in Norway. Among the 49 clustered strains that carried more than four copies of IS6110, 34 had been observed in Norway before 1999. This result demonstrated that a significant number of the clusters were caused by a strain that had been identified previously and that many previously identified outbreaks had not been arrested.

The incidence of TB in Norway has increased from 4.7/100,000 inhabitants in 1997 to 6.6/100,000 in 2001 (11). During the last decade, Norway has received about 50,000 immigrants, the majority of these being from former Yugoslavia, Iraq, and Somalia. During the 1980s, only 28,000 people immigrated to Norway. The majority of these came from Vietnam, Iran, Sri Lanka, and Ethiopia (http://www.ssb.no). Thus, the increase in TB incidence seen lately may be explained in part by the increase in the number of people who have come to Norway from high-burden countries. There were large differences in the incidences of TB among people of different geographic origins living in Norway. Among African immigrants who live in Norway, the incidence was 550/100,000 in 2001, while for ethnic Norwegians, it was 1.9/100,000 (11). It was noteworthy that approximately 30% of the patients from former Yugoslavia and from Somalia were infected with clustered strains. It was difficult to assess whether these immigrants suffered from simultaneous reactivation of a latent infection acquired in their country of origin or whether transmission took place in Norway.

In recent studies from New York City, Geng et al. (9) and Hammer et al. (10) identified 51 different clusters among 546 strains of M. tuberculosis isolated in northern Manhattan from 1990 to 1999. Of these, 24 strains were isolated from foreign-born and U.S.-born persons. The index cases in 17 of these 24 outbreaks were U.S.-born persons (9, 10). In the present study, nine clusters included foreign-born and Norwegian-born persons. The index cases in six of these nine outbreaks were Norwegians. Thus, transmission between different ethnic groups was more common in New York City than it was in Norway; however, as in Norway, it was more common that native-born persons infected immigrants than the opposite both in New York City (9) and in Denmark (14). A total of 74 of 204 immigrants were grouped into 31 clusters in New York City from 1990 to 1999 (9, 10). It seemed that the degree of recent transmission among immigrants in general in Norway was low compared to that in New York City. For persons from Somalia and former Yugoslavia, however, the degree of recent transmission was similar to that found among foreign-born New Yorkers. Although it was shown that some immigrants had been infected in Norway (5), it was likely that the majority were infected prior to arrival. This was also the conclusion in a recent Danish study (14), where 74.9% of Somali patients living in Denmark had been infected before arrival in Denmark.

The largest cluster that was identified by spoligotyping included eight strains (Table 1). These strains had been isolated from seven Somali immigrants and a patient of Norwegian origin. Their spoligotype (777777777413731) was identical to that designated number 48 in a publication by Sola et al. (20). It had been found in strains isolated from patients in metropolitan France, Great Britain, The Netherlands, Denmark, and the United States. Thus, this outbreak may have been due to simultaneous reactivation in many of these patients infected by the same strain abroad. Spoligotype 777777777760731 was represented by strains from four immigrants from East Africa (results not shown). The IS6110 RFLP pattern of these four strains, however, varied from one to four copies, and the strains were thus not considered clustered. This type was designated number 52 by Sola et al. and has been found in 10 different countries and areas of the world (20). Since the pace of the molecular clock of the DR locus appears to be much slower than that of IS6110 and since that spoligotype has been observed in other countries (20), these patients likely were infected before they arrived in Norway. This spoligotype and other spoligotypes found in Norway had also been identified in other countries (18, 20). Since many of the strains that carried fewer than five copies of IS6110 had been identified in other countries, it was possible that this was also the case for strains that carried more than four copies of IS6110. Most outbreaks were generated by strains that had been identified in Norway for many years, but usually these strains were isolated from patients who originated from the same country (Table 2). It was thus believed that many of the clustered immigrant cases had arrived in Norway with latent infections.

Our study demonstrated that the degree of transmission of M. tuberculosis in Norway was very low and included the transmission of imported strains between immigrants and the native population. While the high incidence of TB among immigrants does not present a threat for the native population in Norway, the control of TB in Norway needs to be adapted to the changing epidemiology of M. tuberculosis. Since screening of immigrants for TB at arrival is not sufficient, the control should also focus on latent infections in special population groups. Many outbreaks have been ongoing for several years, and it appears that contact tracing can be improved and that efforts to prevent infected persons from progressing to overt disease can be intensified. The present report therefore supports the new guidelines for TB control in Norway that recommend that preventive treatment should be offered more broadly than has been done to high-risk groups in Norway who are considered to be infected, especially if chest X-rays show fibrotic lesions. Such a strategy might be crucial for the elimination of TB in low-incidence countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kjersti Haugum, Anne M. Klem, Elisabet Rønnild, and Ann-Christine Øvrevik for excellent technical assistance and Nanne Brattås and Vigdis Dahl for help in data collection.

Footnotes

This article was written as part of European Union Concerted Action on TB project QLK2-CT-2000-00630.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bandera, A., A. Gori, L. Catozzi, A. D. Esposti, G. Marchetti, C. Molteni, G. Ferrario, L. Codecasa, V. Penati, A. Matteelli, and F. Franzetti. 2001. Molecular epidemiology study of exogenous reinfection in an area with a low incidence of tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2213-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broekmans, J. F., G. B. Migliori, H. L. Rieder, J. Lees, P. Ruutu, R. Loddenkemper, and M. C. Raviglione. 2002. European framework for tuberculosis control and elimination in countries with a low incidence—recommendations of the World Health Organization (W. H. O.), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD) and Royal Netherlands Tuberculosis Association (KNCV) Working Group. Eur. Resp. J. 19:765-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callister, M. E. J., J. Barringer, S. T. Thanabalasingam, R. Gair, and R. N. Davidson. 2002. Pulmonary tuberculosis among political asylum seekers screened at Heathrow Airport, London, 1995-9. Thorax 57:152-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahle, U. R., P. Sandven, E. Heldal, and D. A. Caugant. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Norway. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1802-1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahle, U. R., P. Sandven, E. Heldal, T. Mannsaaker, and D. A. Caugant. 2003. Deciphering an outbreak of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:67-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale, J. W., D. Brittain, A. A. Cataldi, D. Cousins, J. T. Crawford, J. Driscoll, H. Heersma, T. Lillebaek, T. Quitugua, N. Rastogi, R. A. Skuce, C. Sola, D. van Soolingen, and V. Vincent. 2001. Spacer oligonucleotide typing of bacteria of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: recommendations for standardised nomenclature. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 5:216-219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Boer, A. S., B. Blommerde, P. E. W. de Haas, M. M. G. G. Sebek, K. S. B. Lambregts-van Weezenbeek, M. Dessens, and D. van Soolingen. 2002. False-positive Mycobacterium tuberculosis cultures in 44 laboratories in The Netherlands (1993 to 2000): incidence, risk factors, and consequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4004-4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dye, C., B. G. Williams, M. A. Espinal, and M. C. Raviglione. 2002. Erasing the world's slow stain: strategies to beat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Science 295:2042-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng, E., B. Kreiswirth, C. Driver, J. Li, J. Burzynski, P. DellaLatta, A. LaPaz, and N. W. Schluger. 2002. Changes in the transmission of tuberculosis in New York City from 1990-1999. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:1453-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammer, A. W., T. H. Hugher-Davies, L. B. Reichman, T. J. John, E. Geng, and N. Schluger. 2002. Changes in the transmission of tuberculosis in New York. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:1453-1455. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heldal, E. 2002. Tuberculosis in Norway 2001. MSIS Rapport 30:20. (In Norwegian.) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamerbeek, J., L. Schouls, A. Kolk, M. van Agterveld, D. van Soolingen, S. Kuijper, A. Bunschoten, H. Molhuizen, R. Shaw, M. Goyal, and J. van Embden. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:907-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremer, K., D. van Soolingen, R. Frothingham, W. H. Haas, P. W. M. Hermans, C. Martin, P. Palittapongarnpim, B. B. Plikaytis, L. W. Riley, M. A. Yakrus, J. M. Musser, and J. D. A. van Embden. 1999. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2607-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lillebaek, T., Å. Andresen, J. Bauer, A. Dirksen, S. Glismann, P. de Haas, and A. Kok-Jensen. 2001. Risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission in a low-incidence country due to immigration from high-incidence areas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:855-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lillebaek, T., Å. Andresen, A. Dirksen, E. Smith, L. T. Skovgaard, and A. Kok-Jensen. 2002. Persistent high incidence of tuberculosis in immigrants in a low-incidence country. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:679-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maguire, H., J. W. Dale, T. D. McHugh, P. D. Butcher, S. H. Gillespie, A. Costetsos, H. Al-Ghusein, R. Holland, A. Dickens, L. Marston, P. Wilson, R. Pitman, D. Strachan, F. A. Drobniewski, and D. K. Banerjee. 2002. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in London 1995-7 showing low rate of active transmission. Thorax 57:617-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathema, B., P. J. Bifani, J. Driscoll, L. Steinlein, N. Kurepina, S. L. Moghazeh, E. Shashkina, S. A. Marras, S. Campbell, B. Mangura, K. Shilkret, J. T. Crawford, R. Frothingham, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2002. Identification and evolution of an IS6110 low-copy-number Mycobacterium tuberculosis cluster. J. Infect. Dis. 185:641-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quitugua, T. N., B. J. Seaworth, S. E. Weis, J. P. Taylor, J. S. Gillette, I. I. Rosas, K. C. Jost, Jr., D. M. Magee, and R. A. Cox. 2002. Transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Texas and Mexico. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2716-2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Small, P. M., P. C. Hopewell, S. P. Singh, A. Paz, J. Parsonnet, D. C. Ruston, G. F. Schecter, C. L. Daley, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1994. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in San Francisco. A population-based study using conventional and molecular methods. N. Engl. J. Med. 330:1703-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sola, C., I. Filliol, M. C. Gutierrez, I. Mokrousov, V. Vincent, and N. Rastogi. 2001. Spoligotype database of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: biogeographic distribution of shared types and epidemiologic and phylogenetic perspectives. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:390-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Soolingen, D., P. E. W. de Haas, P. W. M. Hermans, and J. D. A. van Embden. 1994. DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Enzymol. 235:196-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verver, S., D. van Soolingen, and M. W. Borgdorff. 2002. Effect of screening of immigrants on tuberculosis transmission. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 6:121-129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]