Abstract

The full-length proviral genome of a foamy virus infecting a Bornean orangutan was amplified, and its sequence was analyzed. Although the genome showed a clear resemblance to other published foamy virus genomes from apes and monkeys, phylogenetic analysis revealed that simian foamy virus SFVora was evolutionarily equidistant from foamy viruses from other hominoids and from those from Old World monkeys. This finding suggests an independent evolution within its host over a long period of time.

Foamy viruses (FVs) are a subfamily of retroviruses that cause persistent but benign infections in their natural hosts. Because of the harmless nature of FV infections and their extremely broad cell tropism, they are of great interest in the development of FV-derived vectors for vaccines and gene therapy. In primates, FVs have been isolated from monkeys and great apes (3, 4, 6, 31). Furthermore, infections of humans with FVs have been described (1, 5, 14, 28, 30). Only a few full-length simian foamy virus (SFV) genomes have been determined, including those for SFV-1 and SFV-2, viruses obtained from Japanese macaques (renamed SFVmac); SFV-3 (SFVagm), derived from an African green monkey; and SFVcpz and SFVcpz(hu), isolated from chimpanzees and humans, respectively (12, 15, 17, 19, 22, 26). The genomes of other great ape FVs, from gorillas, pygmy chimpanzees, and orangutans, have been partially characterized. An orangutan virus, designated SFVora (formerly named SFV-11), has been isolated, and a partial long-terminal-repeat (LTR) nucleotide sequence has been determined (20). To broaden our knowledge of the diversity and variability of SFVs, in particular those infecting great apes, we have sequenced the genome of an SFV isolated from a Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus).

Blood samples were obtained from orangutans that were housed at the Wanariset Orangutan Reintroduction Center in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. The samples were assayed for antibodies to FV antigens to determine the incidence of infection (34). Of the 108 animals tested, 69.4% were seropositive by the assay. From one seropositive animal, Bella, genomic DNA was isolated and used as a template for the amplification of overlapping PCR fragments representing the complete genome of the virus.

The genome was amplified in three segments. First, a 425-bp pol fragment was amplified in a nested PCR (33). The two reverse PCR primers from that reaction were then used in combination with two forward LTR primers that had been used previously to amplify a small sequence of SFVora. Amplification resulted in a 4,777-bp 5′ LTR-to-pol fragment. Two primers, env/for (5′-TTATATTGGACCCTTGCCTCCTTCCAACGGTTATTTACAT-3′) and env/rev (5′-GGATTATTGTATATTGATTATCCTTAGGGAAGTTCGCCAG-3′), were then designed to bind to the pol (env/for primer) and LTR-to-pol (env/rev primer) fragments. Use of these primers in a single reaction yielded a 6,623-bp fragment that extended from pol into the 3′ LTR. Both long PCRs were performed by using the eLONGase amplification system (Life Technologies B.V., Breda, The Netherlands) with an MgCl2 concentration of 1.9 mM. The amplification was performed for 35 cycles, each consisting of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 65°C, and a 9-min elongation step at 68°C. The PCR products were isolated from agarose gel by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and were cloned in the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.). They were sequenced by using the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator version 3.0 cycle sequencing kit on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence analysis was performed with MacVector 6.0 and AssemblyLIGN (Oxford Molecular Ltd.) software packages.

The borders of the LTRs were determined by alignment and comparison with SFVcpz. The proviral genome of the virus, SFVora, was calculated to be 12,823 bp long. The organization of open reading frames (ORF) in SFVora is typical for FVs, with three genes (gag, pol, and env) encoding the structural proteins, in addition to the small Tas and Bel-2 ORFs.

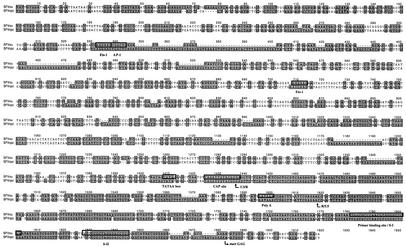

The LTRs were estimated to be 1,621 bp long. The lengths of the U3, R, and U5 regions of the LTR are 1,286, 177, and 158 bp, respectively (Fig. 1). Comparison of a 322-nucleotide (nt) LTR fragment revealed 95% identity between SFVora derived from Bella and the SFV-11 sequence from the orangutan Dodo (20). Analogous to SFVcpz, SFVora has a transcription initiation signal (TATAA box) at position 1258, just upstream from the U3-R junction within the conserved cap site (GGGA) (37) (15), and its polyadenylation site (AATAAA) is located at nt 1438. In the U3 region, two Ets-1 and one AP-1 transcription factor recognition sites are situated at nt 328, 335, and 614, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of SFVora and SFVcpz LTR region sequences. LTR sequences and the segment containing the primer binding site, S-II, and the start of the GAG protein from SFVora and SFVcpz were aligned by using ClustalW and edited manually. Sequence identities are indicated by shaded boxes. Specific features of the SFVora sequence are indicated.

Outside the LTR, two sites involved in the RNA dimerization process, SI and SII, are recognized (7, 10), with the latter overlapping the primer binding site (nt 1625 to 1642). The polypurine tract (AGAGAGGAGAGGG) is located at nt 11188 to 11201.

The gag gene starts at position 1716 and encodes a protein of 624 amino acids (aa). Gag contains three glycine-arginine-rich stretches (GR-I, GR-II, and GR-III; aa 462 to 492, 518 to 541, and 563 to 596, respectively) which are involved in the binding of nucleic acid and in the nuclear localization of the Gag precursor (29). A conserved arginine residue that acts in the intracellular capsid assembly is located at aa position 46 (9). A stretch of regularly spaced hydrophobic residues that may form a coiled-coil motif necessary for Gag-Gag interaction during viral capsid formation extends from aa 125 to 187 (36). Several putative proteolytic cleavage sites, located at positions 285 to 292 (QHIR↓AVTG), 313 to 320 (EGVY↓PVTT), 326 to 333 (RIIN↓ALIG), and 596 to 603 (HAVN↓AVTQ), can be identified (23). However, only the last site appears to be efficiently recognized by the viral protease and may be essential for viral infectivity (18). The ORF of the Pol precursor extends from nt 3547 to 6984 and encodes 1,145 aa. The catalytic domains of the reverse transcriptase (RT) moiety (Y312VDD315) are identical in all FVs (27). The putative proteolytic cleavage sites within Pol are predicted at H140WEN↓QVGH147 (protease-RT cleavage site) and S593MVF↓YTGD600 (RT-RNase H cleavage site; identical to that of SFVagm), while the RNase H-integrase cleavage site (Y748VVN↓NIIK755) is unique among SFVs (24). The env ORF (nt 6923 to 9892) encodes 989 aa. A signal peptide of 18 aa residues (RTLAWLFLFCVLLIVVLV) is predicted at positions 67 to 84, generating a leader protein of 86 aa (38). The cleavage site between the surface (SU) and transmembrane (TM) glycoproteins (R572NRR575↓) (2, 8) generates SU and TM glycoproteins of 486 and 417 aa, respectively. Located in the N terminus of the TM protein is a fusion peptide containing conserved hydrophobic residues (L581-XX-M584-XXX-L588-XX-A591-V592-XX-L595-XX-I598). The charged residues in the membrane-spanning domain of TM (25), in addition to the endoplasmic reticulum retrieval signal (K988RK990), are all conserved in the TM protein (2, 13, 38). On the basis of a comparison with SFVcpz(hu), an internal promoter sequence was identified at nt 9583 to 9638 within the env gene [88 and 91% similarity with the SFVcpz(hu) and SFVcpz promoters, respectively]. Two smaller ORFs that encode the accessory proteins Tas and Bet can be distinguished. The Tas ORF is located at positions 9862 to 10698 and encodes a protein of 278 aa. The Bel-2 ORF has a coding capacity of 321 aa (positions 10589 to 11554).

The SFVora Gag protein has relatively low identity with other primate SFV Gag proteins compared to that of the polymerase and envelope proteins (Table 1). This is in agreement with the findings of others (32, 38). In this respect, FVs resemble the primate T-lymphotropic viruses more than the immunodeficiency viruses (16, 21). Unlike human immunodeficiency virus, FVs and the primate T-lymphotropic viruses are highly cell associated in vivo, with cell-free virus rarely being detectable in the blood, suggesting either cell-to-cell spread or dissemination by clonal expansion. Such evolutionarily acquired viral strategies may preclude the necessity of the virus to accumulate envelope mutations to escape the surveillance of the immune system (11, 32, 39).

TABLE 1.

Amino acid comparisons of SFV structural proteinsa

| Protein | SFVora vs SFVcpz

|

SFVora vs SFVcpz(hu)

|

SFVora vs SFV-1

|

SFVora vs SFV-3

|

SFVcpz vs SFVcpz(hu)

|

SFVcpz vs SFV-1

|

SFVcpz vs SFV-3

|

SFVcpz(hu) vs SFV-1

|

SFVcpz(hu) vs SFV-3

|

SFV-1 vs SFV-3

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | % ID | % SIM | |

| Gag | 49 | 14 | 50 | 14 | 45 | 14 | 45 | 13 | 87 | 4 | 44 | 15 | 48 | 16 | 44 | 16 | 48 | 17 | 65 | 2 |

| Pol | 77 | 10 | 77 | 9 | 76 | 11 | 75 | 12 | 94 | 2 | 78 | 11 | 76 | 12 | 78 | 11 | 77 | 11 | 85 | 8 |

| Env | 67 | 16 | 67 | 16 | 63 | 17 | 62 | 16 | 90 | 4 | 66 | 17 | 65 | 16 | 67 | 16 | 66 | 16 | 72 | 13 |

ID, identity; SIM, similarity.

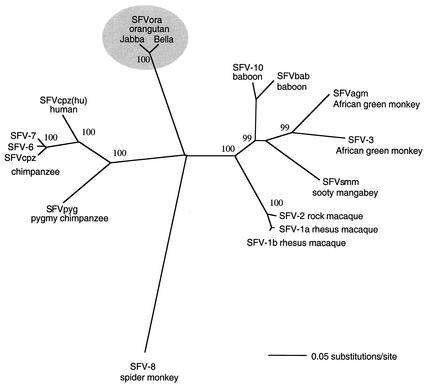

Surprisingly, the protein sequence identities of SFVora with SFVcpz(hu) and SFVcpz were only slightly higher than those with the viruses from Old World monkeys, which suggests an equidistant evolutionary relationship of SFVora with FVs from monkeys and other great apes. Phylogenetic analysis of the different proteins confirmed this notion (data not shown). To validate our assumption, we expanded our data set by using 425-bp fragments of the pol gene from GenBank and EMBL databases to establish the evolutionary relationships between a larger set of primate FVs. In addition, the pol region from another SFVora (isolate Jabba; 98% identity with SFVora isolate Bella) was added to the data set. Phylogenetic analysis of pol sequences was performed by using PAUP 4.0 B10 beta (35), and the phylogenetic tree is depicted in Fig. 2. The tree was rooted with the only FV sequence available from a New World monkey (SFV-8 from a spider monkey). Viruses isolated from Old World monkeys from Africa (SFVbab, SFVagm, SFVsmm) and Asia (SFVmac) and those from humans and common and pygmy chimpanzees form two monophyletic groups, both identified with 100% confidence. From our data it is evident that SFVora is distinct from other known SFVs. SFVora does not cluster with either the African great ape viruses or other SFVs. The evolutionary distances between the most closely related members of each group and SFVora were 0.3657 (SFVbab10) and 0.3810 (SFVpyg). Our analyses indicate that FVs from orangutans share a common ancestor virus with other primate FVs but that SFVora has evolved independently in its host over a long time period.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of primate FV pol sequences. A phylogenetic tree based on the analysis of a 425-bp pol (integrase) fragment is shown. Distances were determined by using the Kimura two-parameter method, and the tree was constructed by using the neighbor-joining method. The numbers at the nodes indicate the percentages of probability after analysis of 1,000 bootstrap resamplings. The horizontal bar indicates the number of base substitutions per site. The EMBL database accession number for SFVora isolate Jabba is AJ556783.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of SFVora strain Bella has been deposited in the EMBL sequence database under accession number AJ 544579.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Heriyanto and the staff at the Wanariset Orangutan Reintroduction Centre for assistance with sample collection, M. O. McClure, O. Erlwein, and M. Schweizer for serological analyses and helpful discussions, and N. Otting, N. de Groot, and colleagues at the Biomedical Primate Research Centre for support and technical assistance.

This work was supported by the EC grant BMH4-CT97-2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achong, B. G., P. W. A. Mansell, M. A. Epstein, and P. Clifford. 1971. An unusual virus in cultures from a human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 46:299-302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansal, A., K. L. Shaw, B. H. Edwards, P. A. Goepfert, and M. J. Mulligan. 2000. Characterization of the R572T point mutant of a putative cleavage site in human foamy virus Env. J. Virol. 74:2949-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieniasz, P. D., A. Rethwilm, R. Pitman, M. D. Daniel, I. Chrystie, and M. O. McClure. 1995. A comparative study of higher primate foamy viruses, including a new virus from a gorilla. Virology 207:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blewett, E. L., D. H. Black, N. W. Lerche, G. White, and R. Eberle. 2000. Simian foamy virus infections in a baboon breeding colony. Virology 278:183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks, J. I., E. W. Rud, R. G. Pilon, J. M. Smith, W. M. Switzer, and P. A. Sandstrom. 2002. Cross-species retroviral transmission from macaques to human beings. Lancet 360:387-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broussard, S. R., A. G. Comuzzie, K. L. Leighton, M. M. Leland, E. M. Whitehead, and J. S. Allan. 1997. Characterization of new simian foamy viruses from African nonhuman primates. Virology 237:349-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cain, D., O. Erlwein, A. Grigg, R. A. Russell, and M. O. McClure. 2001. Palindromic sequence plays a critical role in human foamy virus dimerization. J. Virol. 75:3731-3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffin, J. 1986. Genetic variation in AIDS viruses. Cell 89:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eastman, S. W., and M. L. Linial. 2001. Identification of a conserved residue of foamy virus Gag required for intracellular capsid assembly. J. Virol. 75:6857-6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erlwein, O., D. Cain, N. Fischer, A. Rethwilm, and M. O. McClure. 1997. Identification of sites that act together to direct dimerization of human foamy virus RNA in vitro. Virology 229:251-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falcone, V., J. Leupold, J. Clotten, E. Urbanyi, O. Herchenroder, W. Spatz, B. Volk, N. Bohm, A. Toniolo, D. Neumann-Haefelin, and M. Schweizer. 1999. Sites of simian foamy virus persistence in naturally infected African green monkeys: latent provirus is ubiquitous, whereas viral replication is restricted to the oral mucosa. Virology 257:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flugel, R. M., A. Rethwilm, B. Maurer, and G. Darai. 1987. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the env gene and its flanking regions of the human spumaretrovirus reveals two novel genes. EMBO J. 6:2077-2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goepfert, P. A., K. L. Shaw, G. D. Ritter, Jr., and M. J. Mulligan. 1997. A sorting motif localizes the foamy virus glycoprotein to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol. 71:778-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heneine, W., W. M. Switzer, P. Sandstrom, J. Brown, S. Vedapuri, C. A. Schable, A. S. Khan, N. W. Lerche, M. Schweizer, D. Neumann-Haefelin, L. E. Chapman, and T. M. Folks. 1998. Identification of a human population infected with simian foamy viruses. Nat. Med. 4:403-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herchenroder, O., R. Renne, D. Loncar, E. K. Cobb, K. K. Murthy, J. Schneider, A. Mergia, and P. A. Luciw. 1994. Isolation, cloning, and sequencing of simian foamy viruses from chimpanzees (SFVcpz): high homology to human foamy virus (HFV). Virology 201:187-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuiken, C., B. Foley, B. Hahn, P. Marx, F. McCutchan, J. Mellors, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber (ed.). 2001. HIV sequence compendium 2001. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex.

- 17.Kupiec, J. J., A. Kay, M. Hayat, R. Ravier, J. Peries, and F. Galibert. 1991. Sequence analysis of the simian foamy virus type 1 genome. Gene 101:185-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linial, M. L. 1999. Foamy viruses are unconventional retroviruses. J. Virol. 73:1747-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurer, B., and R. M. Flugel. 1988. Genomic organization of the human spumaretrovirus and its relatedness to AIDS and other retroviruses. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 4:467-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClure, M. O., P. D. Bieniasz, T. F. Schulz, I. L. Chrystie, G. Simpson, A. Aguzzi, J. G. Hoad, A. Cunningham, J. Kirkwood, and R. A. Weiss. 1994. Isolation of a new foamy retrovirus from orangutans. J. Virol. 68:7124-7130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meertens, L., R. Mahieux, P. Mauclère, J. Lewis, and A. Gessain. 2002. Complete sequence of a novel highly divergent simian T-cell lymphotropic virus from wild-caught red-capped mangabeys (Cercocebus torquatus) from Cameroon: a new primate T-lymphotropic virus type 3 subtype. J. Virol. 76:259-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mergia, A., and P. A. Luciw. 1991. Replication and regulation of primate foamy viruses. Virology 184:475-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfrepper, K.-I., M. Löchelt, H.-R. Rackwitz, M. Schnölzer, H. Heid, and R. M. Flügel. 1999. Molecular characterization of proteolytic processing of the Gag proteins of human spumavirus. J. Virol. 73:7907-7911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfrepper, K.-I., H.-R. Rackwitz, M. Schnölzer, H. Heid, M. Löchelt, and R. M. Flügel. 1998. Molecular characterization of proteolytic processing of the Pol proteins of human foamy virus reveals novel features of the viral protease. J. Virol. 72:7648-7652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietschmann, T., H. Zentgraf, A. Rethwilm, and D. Lindemann. 2000. An evolutionarily conserved positively charged amino acid in the putative membrane-spanning domain of the foamy virus envelope protein controls fusion activity. J. Virol. 74:4474-4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renne, R., E. Friedl, M. Schweizer, U. Fleps, R. Turek, and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1992. Genomic organization and expression of simian foamy virus type 3 (SFV-3). Virology 186:597-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinke, C. S., P. L. Boyer, M. D. Sullivan, S. H. Hughes, and M. L. Linial. 2002. Mutation of the catalytic domain of the foamy virus reverse transcriptase leads to loss of processivity and infectivity. J. Virol. 76:7560-7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandstrom, P. A., K. O. Phan, W. M. Switzer, T. Fredeking, L. Chapman, W. Heneine, and T. M. Folks. 2000. Simian foamy virus infection among zoo keepers. Lancet 355:551-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schliephake, A. W., and A. Rethwilm. 1994. Nuclear localization of foamy virus Gag precursor protein. J. Virol. 68:4946-4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweizer, M., V. Falcone, J. Gänge, R. Turek, and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1997. Simian foamy virus isolated from an accidentally infected human individual. J. Virol. 71:4821-4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schweizer, M., and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1995. Phylogenetic analysis of primate foamy viruses by comparison of pol sequences. Virology 207:577-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweizer, M., H. Schleer, M. Pietrek, J. Liegibel, V. Falcone, and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1999. Genetic stability of foamy viruses: long-term study in an African green monkey population. J. Virol. 73:9256-9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schweizer, M., R. Turek, H. Hahn, A. Schliephake, K. O. Netzer, G. Eder, M. Reinhardt, A. Rethwilm, and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1995. Markers of foamy virus infections in monkeys, apes, and accidentally infected humans: appropriate testing fails to confirm suspected foamy virus prevalence in humans. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweizer, M., R. Turek, M. Reinhardt, and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1994. Absence of foamy virus DNA in Graves' disease. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:601-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swofford, D. L. 2002. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods) 4.0 B10. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts. [Online.]

- 36.Tobaly-Tapiero, J., P. Bittoun, M.-L. Giron, M. Neves, M. Koken, A. Saïb, and H. de Thé. 2001. Human foamy virus capsid formation requires an interaction domain in the N terminus of Gag. J. Virol. 75:4367-4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varmus, H., and R. Swanstrom. 1982. Replication of retroviruses, p. 369-512. In R. Weiss, N. Teich, H. Varmus, and J. Coffin (ed.), RNA tumor viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Wang, G., and M. J. Mulligan. 1999. Comparative sequence analysis and predictions for the envelope glycoproteins of foamy viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 80:245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wattel, E., J.-P. Vartanian, C. Pannetier, and S. Wain-Hobson. 1995. Clonal expansion of human T-cell leukemia virus type I-infected cells in asymptomatic and symptomatic carriers without malignancy. J. Virol. 69:2863-2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]