Abstract

The relationship between virus-specific CD8+-T-cell responses and viral persistence was studied in mice by using Hantaan virus (HTNV). We first established a simple method for measuring levels of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. Next, to produce a mouse model of persistent HTNV infection, newborn mice were inoculated subcutaneously within 24 h of birth with 1 or 0.1 50% newborn mouse lethal dose of HTNV. All mice that escaped lethal infection were persistently infected with HTNV until at least 30 days after virus inoculation and had no virus-specific CD8+ T cells producing gamma interferon (IFN-γ). Subsequently, the virus was eliminated from some of the mice, depending on the appearance of functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells, which have the ability to produce IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and have cytotoxic activity. Neutralizing antibodies were detected in all mice, regardless of the presence or absence of virus. In the acute phase, which occurs within 30 days of infection, IFN-γ-producing HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells were detected on day 15 after virus inoculation. However, TNF-α production and the cytotoxic activity of these specific CD8+ T cells were impaired and HTNV was not removed. Almost all of these specific CD8+ T cells disappeared by day 18. These results suggest that functional HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells are important for clearance of HTNV.

Hantaviruses constitute a genus in the family Bunyaviridae. They are spherical, enveloped viruses with a genome consisting of three segments of single-stranded, negative-sense RNA. The three segments are designated as the large, medium, and small segments, and they encode RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, two surface glycoproteins (G1 and G2), and nucleocapsid (N) protein, respectively (29-31). Hantavirus infections are known to cause two serious and often fatal human diseases, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) (28).

Humans are infected with hantaviruses from rodent reservoirs that are persistently infected without signs of disease (28). More than 100,000 cases of HFRS are reported annually in Asia and Europe; most are reported in China (14, 33). Hantaan virus (HTNV), Seoul virus, Dobrava virus, Saaremaa virus, and Puumala virus are known to cause HFRS (28, 32). HPS appears to be confined to the Americas and is lethal (>40% mortality) (28). It is known that Sin Nombre virus, New York virus, Black Creek Canal virus, Bayou virus, Lagna Negra virus, and Andes virus cause HPS (18, 28). Distinct hantaviruses are associated with a single rodent species. In addition, it is generally believed that hantaviruses have coevolved with their rodent hosts, because nearly identical phylogenetic trees can be constructed for hantaviral host mitochondrial DNA sequences and viral RNA sequences (23).

Hantaviruses have no cytopathic effect, or an incomplete effect, on cultured cells and are nonlytic. It is believed that rodent reservoirs infected with these viruses maintain lifelong persistent infection despite the presence of neutralizing antibodies (3, 6). Mechanisms of persistent hantavirus infection in rodent reservoirs are poorly understood. A possible mechanism is thought to be that the viruses escape the host immune system by changing genetically or by suppressing host immunity against hantaviruses. Several groups have studied genetic changes and hypothesized that virus quasispecies exist in naturally infected rodents (10, 24-26) or that hantavirus cell culture alters the viral genome (15, 17). However, it has not been established whether suppression of the immune response against hantaviruses occurs in rodents.

Mice infected with certain lymphocytic choriomeningitis viruses (LCMV) have persistent infection due to the absence of cellular immune responses but continue to produce virus-specific antibodies (4). Persistent LCMV infection in mice is similar to persistent hantavirus infection in rodent reservoirs, since both show antibody production and a nonlytic viral infection. Therefore, we hypothesized that persistent hantavirus infection in infected rodent reservoirs is caused by the absence of hantavirus-specific cellular responses.

In this study, we first established a method to measure levels of HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells. Second, to investigate whether the absence of HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells relates to viral persistence, we tried to produce a mouse model of persistent HTNV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Pregnant and 5-week-old female BALB/c/Jcl mice (H-2d) were obtained from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan). All mice were treated according to the laboratory animal control guidelines of our institute, which conform to those of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. All experiments were carried out in a class P3 facility.

Viral infection of mice.

HTNV cl-1 (9) was obtained by plaque cloning HTNV strain 76-118. The virus was propagated in the E6 clone of Vero cells (Vero E6) grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM; Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Within 24 h of birth, neonatal BALB/c mice were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) with 1 or 0.1 50% newborn mouse lethal dose (NMLD50) of HTNV. Five-week-old adult mice were inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 2,400 focus-forming units (FFU), which is 2,000 NMLD50s, of HTNV.

Preparation of APC.

Murine macrophage-like cell line P388D1 (H-2d) was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Nissui) supplemented with 5% FBS and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME). P388D1 cells were infected with HTNV as described previously (36). Briefly, to enhance HTNV infection, monoclonal antibody (MAb) 1G8, which combines with the HTNV G2 envelope glycoprotein, was mixed with an equal volume of culture fluid that contained HTNV for 1 h at 37°C. The mixtures were inoculated onto P388D1 cell monolayers. After a 1-hr incubation at 37°C, the mixtures were removed and RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% FBS and 50 μM 2-ME was added to the P388D1 cells. After three to four passages, 70 to 80% of P388D1 cells were infected with HTNV and used as antigen-presenting cells (APC).

Fluorescence staining and flow cytometry.

Spleen single-cell suspensions were obtained by homogenizing the spleens through a mesh. Erythrocytes were lysed with 0.83% NH4Cl. To detect intracellular gamma interferon (IFN-γ), spleen cells were added to 96-well round-bottomed plates at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 μM 2-ME, 20 U of murine recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2; Sigma)/ml, and 10 μg of brefeldin A (Sigma)/ml, along with HTNV-infected or uninfected P388D1 cells. The P388D1 cells were cocultured at a concentration of 1.5 × 104 to 5 × 105 cells/well with the spleen cells. After a 6-hr incubation, the cells were washed with washing buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 1% bovine serum albumin [BSA] and 0.1% NaN3) and stained with Tricolor-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD8α (Ly-2) MAb (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, Calif.) for 30 min on ice. Cells were then washed with washing buffer and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde-PBS. After a 20-min incubation at room temperature, the cells were washed with washing buffer, resuspended in PBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.5% saponin (Sigma), and 0.1% NaN3, and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ MAb (Caltag Laboratories) and R-phycoerythrin-conjugated rat anti-mouse tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) MAb (Caltag Laboratories), incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and washed twice with PBS, 0.5% BSA, 0.5% saponin, and 0.1% NaN3. Cells were given one final wash with washing buffer before analysis.

The cell samples were analyzed with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson), and the data analysis was conducted with CellQuest (Becton Dickinson).

N protein detection by Western blotting of HTNV-infected mouse lung.

Western blotting was performed by using previously published methods (39). Briefly, 20 μl of 10% lung homogenate was used as an antigen. Polyclonal rabbit anti-N protein antibody (diluted 1:800 with PBS) (2), prepared by immunizing a rabbit with truncated N protein expressed in Escherichia coli, was used to detect the antigens on the membrane. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (diluted 1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) was the secondary antibody. Results of Western blotting were quantified by densitometry with NIH Image 1.6.1 analysis software. NIH Image was developed at the National Institutes of Health and is available on the Internet (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Virus titration in HTNV-infected newborn mouse lungs.

Lungs were prepared in PBS as 10% homogenates. The homogenates were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and serial 10-fold dilutions of the supernatants were inoculated onto Vero E6 cell monolayers in 96-well plastic plates. After a 1-hr incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the supernatants were discarded and the wells were overlaid with EMEM containing 5% FBS and 1.5% carboxymethylcellulose. After incubation for 7 days, the monolayers were fixed with acetone-methanol (1:1) and dried. Virus focus detection was carried out by using a previously described method (2). Briefly, polyclonal rabbit anti-N protein antibody was added to the 96-well plate monolayers. The plate was incubated for 1 h at 37°C, washed with PBS, and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at 37°C. The plate was washed with PBS, and virus foci were stained by 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate (Sigma Chemical Co.) as described in the manufacturer's instructions.

FRNTs.

Focus reduction neutralization tests (FRNTs) were carried out by using previously described methods (2). Briefly, 100 μl of serial twofold dilutions of sera that had been heat inactivated for 30 min at 56°C were mixed with an equal volume of virus suspension containing 400 FFU of virus at 37°C for 1 h. Then, 50 μl of the mixture was inoculated onto Vero E6 cell monolayers in 96-well plates, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in a 5% CO2 incubator. After adsorption for 1 h, the wells were overlaid with EMEM containing 1.5% carboxymethylcellulose. The plates were incubated for 7 days, and the monolayers were fixed with acetone-methanol (1:1) and dried. Virus foci detection was performed as described above. The neutralizing antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution resulting in a reduction of greater than 80% in the number of infected cell foci.

Cytotoxicity assay.

Spleen cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μM 2-ME so that there were 5 × 106 spleen cells/ml. Spleen cells were dispensed into a 24-well-plate in 1-ml aliquots. Twenty microliters of HTNV (1.6 × 107 FFU/ml) was added to each well, and the spleen cells were cultured for 5 days. Murine IL-2 (20 U/ml; Sigma) was added on day 5 in 1 ml of fresh RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μM 2-ME, and then the spleen cells were cultured for 2 more days. Cultured spleen cells were used for the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. For the LDH assay, RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% FBS and 50 μM 2-ME was used. Target cells, either HTNV-infected P388D1 cells (positive control) or uninfected P388D1 cells (negative control), were added to 96-well round-bottomed plates at 104 cells/well. Spleen cells stimulated in vitro were added to the plates at various effector cell/target cell (E/T) ratios. The plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the supernatant was used to detect LDH by using a cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche). The percent cytotoxicity was calculated as described in the manufacturer's instructions. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Removal of adherent cells from among spleen cells.

To remove adherent cells, spleen cells suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μM 2-ME were incubated in a 150-cm2 cell culture flask for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using EXCEL multivariate analysis version 4.0 add-in software (ESUMI, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Establishing a method for counting HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells.

Techniques to directly count antigen-specific CD8+ T cells include staining with tetrameric peptide-major histocompatibility complex and detecting intracellular IFN-γ in CD8+ T cells after peptide stimulation (1, 7, 21). These techniques have been used to enumerate virus-specific CD8+ T cells in cases of various viral infections in mice and humans. However, it is not possible to use these techniques with hantavirus-infected BALB/c mice (H-2d), because CD8+-T-cell epitopes have not yet been identified. In this study, HTNV-infected P388D1 cells (H-2d) were used instead of peptide. After stimulation of spleen cells by coculture with P388D1 cells, we tried to detect intracellular IFN-γ in CD8+ T cells.

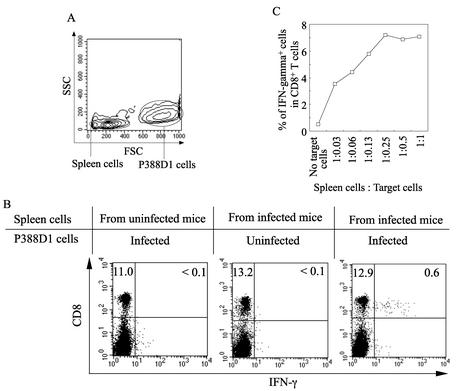

IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells were detected in a combination of spleen cells from HTNV-infected BALB/c mice and HTNV-infected P388D1 cells but not in other combinations (Fig. 1A and B), showing that our method was successful. Then, to investigate the most effective ratio of spleen cells to P388D1 cells, different quantities of HTNV-infected P388D1 cells were added to a constant number of spleen cells (Fig. 1C). The number of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells was dependent on the number of P388D1 cells. The most effective response was obtained when the ratio of spleen cells to P388D1 cells was between 1:0.25 and 1:1. In subsequent experiments, IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells were measured with a spleen cell-to-P388D1 cell ratio of 1:0.5.

FIG. 1.

Establishment of a method for measuring levels of HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ. Spleen cells from BALB/c mice with or without HTNV infection were incubated with HTNV-infected or uninfected P388D1 cells for 6 h in the presence of brefeldin A and IL-2. (A) Data from forward scatter (FSC) versus side scatter (SSC) dot plots of cocultured spleen cells and P388D1 cells. (B) Evaluation of CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells was carried out using flow cytometry. The gates were set for spleen cells as in the experiments described for panel A. Spleen cells for experiments whose results are shown in panel B were obtained from HTNV-infected (day 9 after infection) or uninfected adult BALB/c mice and cocultured with P388D1 cells as indicated in panel B. (C) Spleen cells from HTNV-infected adult mice were incubated with P388D1 cells infected by HTNV. Data are presented as frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD8+ cells detected at different ratios of spleen cells to P388D1 cells.

HTNV-specific CD8+-T-cell responses in HTNV-infected adult BALB/c mice.

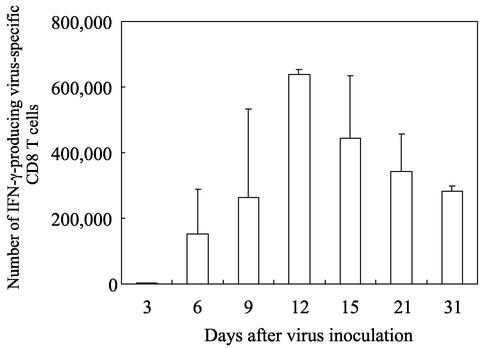

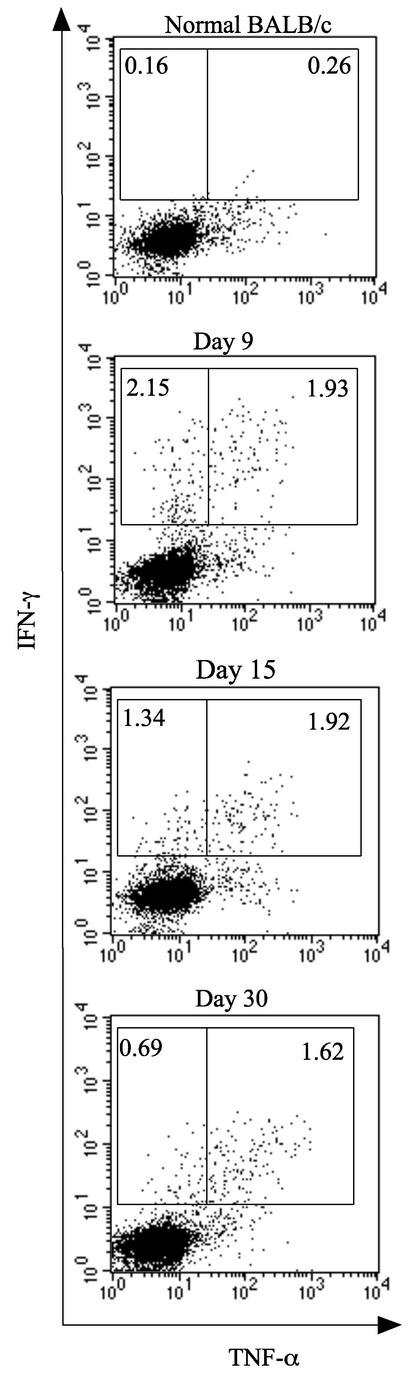

To analyze the HTNV-specific CD8+-T-cell responses in HTNV-infected adult BALB/c mice, we counted the HTNV-specific CD8+T cells producing IFN-γ (Fig. 2). Three days after HTNV inoculation, there were almost no IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells. Twelve days after inoculation, the IFN-γ+ CD8+-T-cell response peaked. About 600,000 cells per spleen were HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells on day 12. About 300,000 cells per spleen were HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells on day 31 after inoculation. Next, we also measured levels of TNF-α-producing specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3). At day 9, about 47% of the IFN-γ+ cells were able to produce TNF-α. The percentage of TNF-α+ cells among IFN-γ+ cells increased with time, and most of the HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells produced both TNF-α and IFN-γ on day 30. In addition, Western blotting failed to detect N protein in the lungs of any mice (data not shown), indicating that HTNV infection in adult mice is transient.

FIG. 2.

Immune responses of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in HTNV-infected adult BALB/c mice. Adult BALB/c mice were inoculated with 2,400 FFU of HTNV. Spleen cells were obtained from three HTNV-infected BALB/c mice on days 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 21, and 31 after HTNV inoculation. Spleen cells and HTNV-infected P388D1 cells were cocultured at a ratio of 1:0.5 for 6 h in the presence of brefeldin A and IL-2. The number of CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells per spleen was measured using flow cytometry. Data represent the average numbers from three mice. Bars represent the standard deviation at each time point. No CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells were detected from a combination of the spleen cells and uninfected P388D1 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

TNF-α production by HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ in HTNV-infected adult BALB/c mice. Adult BALB/c mice were inoculated with 2,400 FFU of HTNV. Spleen cells were obtained from HTNV-infected BALB/c mice on days 9, 15, and 30 after HTNV inoculation. Spleen cells and HTNV-infected P388D1 cells were cocultured at a ratio of 1:0.5 for 6 h in the presence of brefeldin A and IL-2. TNF-α production by CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells was detected using flow cytometry. The gates were set for CD8+ T cells, and the numbers are the percentages of TNF-α− IFN-γ+ and TNF-α+ IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells. Data from a representative experiment are shown.

Persistence of HTNV in newborn mice.

We have shown that when BALB/c mice are inoculated with a sublethal HTNV dose within 24 h of birth, most mice retain virus in the lungs for 8 weeks (37). To further examine viral persistence, newborn mice were inoculated s.c. with 1 NMLD50 or 0.1 NMLD50 of HTNV and we attempted to detect N protein in the lungs by Western blotting from 30 to 120 days after virus inoculation.

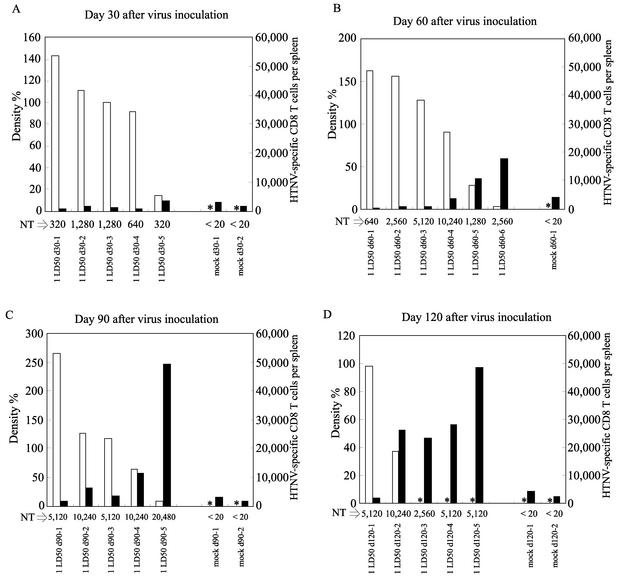

N protein was detected in all the mice 30 days after virus inoculation (Fig. 4A). Although all the mice retained the N protein after 60 days, only a small amount was found in one mouse (Fig. 4B). The number of mice that failed to retain N protein increased over time (Fig. 4C and D). The same tendency was seen in newborn mice inoculated with 0.1 NMLD50 of virus (data not shown). However, the group of mice inoculated with 1 NMLD50 tended to retain N protein for a longer period than mice inoculated with 0.1 NMLD50 (data not shown). These data show that all HTNV-inoculated mice became persistently infected after 30 days, and virus was detected in some mice even at 120 days. We previously reported that HTNV replicates in many peripheral organs of newborn mice infected with high doses of virus (9). In newborn mice infected with low doses of virus (1 NMLD50 and 0.1 NMLD50), however, there was more N protein in the lungs than in any other organ (data not shown). Although N protein was also detected in the brains, there was only one-tenth to one-hundredth of the amounts in lungs (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Results of measuring amounts of N protein in the lungs, neutralizing antibody titers (NT) in the sera, and the IFN-γ-producing specific CD8+-T-cell responses in HTNV-infected newborn mice. Within 24 h of birth, newborn mice were inoculated s.c. with 1 NMLD50 (1 LD50) of HTNV or EMEM for mock infection. On days 30 (A), 60 (B), 90 (C), and 120 (D) after virus inoculation, the lungs, sera, and spleens were obtained from surviving mice. White bars represent the amounts of N protein, and black bars represent the numbers of HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ. Amounts of N protein in the lungs were measured by Western blotting. Band density was determined by NIH Image 1.6.1 analysis software. To calculate the density of each point, the median density for newborn mice infected with 1 NMLD50 of HTNV on day 30 was set at 100%. Asterisks show that no band was detected. FRNTs were carried out using sera. The neutralizing antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution resulting in a reduction of greater than 80% in the number of infected cell foci. To detect HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ, spleen cells and HTNV-infected P388D1 cells were cocultured at a ratio of 1:0.5 for 6 h in the presence of brefeldin A and IL-2. Data show the number of IFN-γ-producing virus-specific CD8+ T cells per spleen. No CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells were detected from a combination of the spleen cells and uninfected P388D1 cells (data not shown). These results were obtained in two independent experiments. d30-1, sample 1 on day 30.

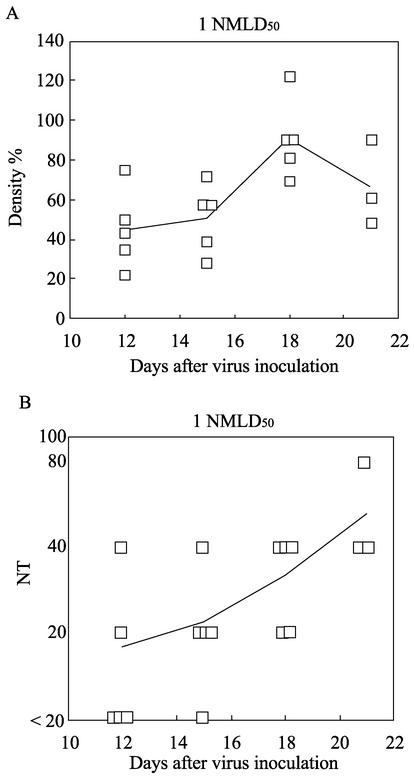

Although we tried to perform virus titrations with mouse lung, we were not successful. As shown in Fig. 4, all HTNV-infected mice had high neutralizing antibody titers that seemed to prevent virus titration. In addition, neutralizing antibodies were not important for viral persistence, since they were detected in the presence of N protein.

HTNV-specific CD8+-T-cell responses.

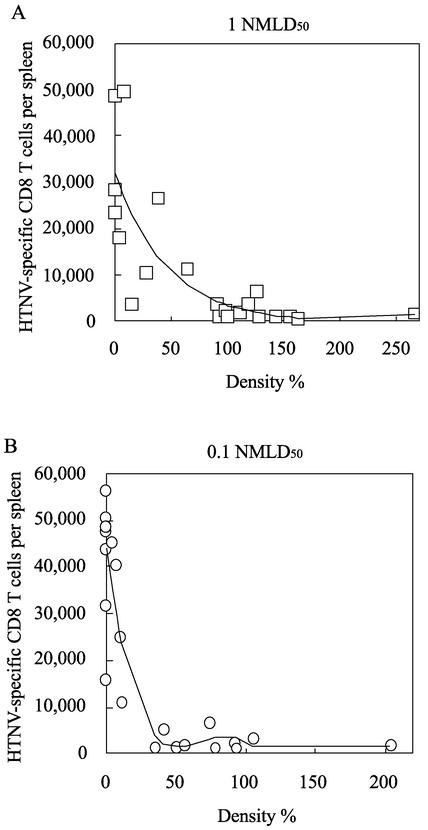

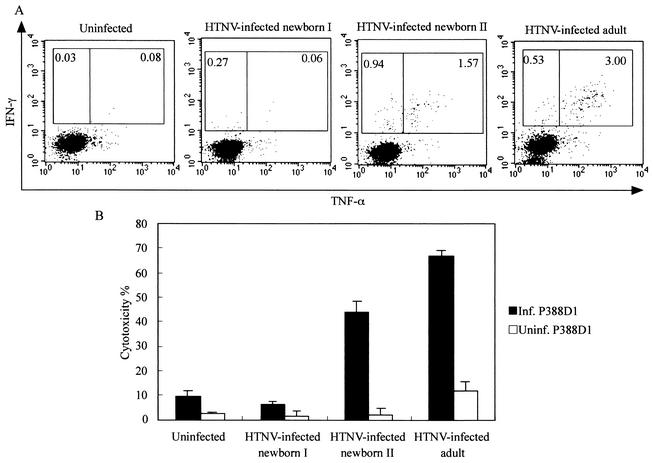

To examine the relationship between viral persistence and HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells, we measured HTNV-specific CD8+-T-cell responses in newborn mice. Almost no IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells were found at 30 days (Fig. 4A). The number of mice with IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells increased with time. In particular, at 120 days after virus inoculation, a number of specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ were detected in most of the mice inoculated with HTNV (Fig. 4D). In addition, mice with large numbers of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells tended to have no N protein or only small amounts. This tendency was observed in newborn mice inoculated with 0.1 NMLD50 of virus (data not shown). Moreover, as with the N protein in the lungs, the N protein in the brains disappeared after the appearance of HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells (data not shown). To further analyze the relationship between IFN-γ-producing virus-specific CD8+ T cells and viral persistence, we drew diagrams showing correlation between the amounts of N protein in the lungs and the numbers of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5). The diagrams for both the 1-NMLD50 and 0.1-NMLD50 infections showed that the amounts of N protein decreased in proportion to the increases in the numbers of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells. Each regression curve revealed a strong correlation between the amount of N protein and the number of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells. These results suggest that IFN-γ-producing virus-specific CD8+ T cells interrupt hantavirus persistence. To analyze other functions of HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells in HTNV-infected newborn mice, we investigated TNF-α production and cytotoxic activity (Fig. 6). We obtained similar results with HTNV-infected newborn mice in the convalescent phase and HTNV-infected adult mice (Fig. 6, newborn II and adult). In both sets of mice, more than half of the IFN-γ-producing cells were able to produce TNF-α (Fig. 6A, newborn II and adult) and cytotoxicity from these spleen cells was detected (Fig. 6B, newborn II and adult). Similar results were observed with spleen cells that included many IFN-γ-producing cells isolated from HTNV-infected newborn mice on day 120 after virus inoculation (data not shown). These results show that the HTNV-specific CD8+-T-cell functions of HTNV-infected newborn mice in the convalescent phase are comparable with those in HTNV-infected adult mice. By contrast, spleen cells that included few IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells had no cytotoxic activity (Fig. 6B, newborn I). In addition, we obtained similar results for spleen cells that included no IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells isolated from HTNV-infected newborn mice on day 30 after virus inoculation (data not shown). There was a correlation between the quantity of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells and cytotoxic activity.

FIG. 5.

Correlation between the amount of N protein and the number of virus-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ. N protein and IFN-γ-producing virus-specific CD8+-T-cell data were obtained from Fig. 4 (A) and from experiments with newborn mice infected with 0.1 NMLD50 of HTNV (B). Correlation diagrams and regression curves for each virus dose were drawn by EXCEL multivariate analysis version 4.0 add-in software made by ESUMI. The R2 value was calculated for each regression curve (1 NMLD50, R2 = 0.64; 0.1 NMLD50, R2 = 0.83).

FIG. 6.

TNF-α production by IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells and cytotoxic activity of spleen cells obtained from HTNV-infected newborn mice. Spleen cells isolated from uninfected adult mice, HTNV-infected newborn mice (1 NMLD50) at day 75 after virus inoculation, and HTNV-infected adult mice (2,400 FFU) at day 60 after virus inoculation were tested for TNF-α production (A) and cytotoxic activity (B). Cells classified as “HTNV-infected newborn I” included few IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells and those classified as “HTNV-infected newborn II” included many IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells. (A) To detect TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells, spleen cells and HTNV-infected P388D1 cells were cocultured at a ratio of 1:0.5 for 6 h in the presence of brefeldin A and IL-2. TNF-α production by CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells was detected using flow cytometry. The gates were set for CD8+ T cells, and the numbers are the percentages of TNF-α− IFN-γ+ and TNF-α+ IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells. (B) For the cytotoxic assay, spleen cells were cultured as described in Materials and Methods. The spleen cells were tested using an LDH release cytotoxic assay. HTNV-infected P388D1 cells (Inf. P388D1; positive control) and uninfected P388D1 cells (Uninf. P388D1; negative control) were used as target cells. Bars represent the standard deviations. E/T ratio, 20. Data from a representative experiment are shown.

Immune responses of HTNV-infected newborn mice in the acute phase.

In several experiments studying LCMV infection, neonatal lymphocytes were naturally prone to the induction of tolerance (4). LCMV-infected newborn mice have lifelong persistent infection without virus-specific CD8+ T cells. However, recent studies have shown that newborn mice inoculated with certain viruses are capable of generating antiviral CD8+ T cells that can eliminate virus-infected cells (20, 27). This shows that in the neonatal phase, the virus-induced immune responses vary. To examine the immune responses of HTNV-infected newborn mice in the acute phase, we measured the amounts of N protein, neutralizing antibody titers, and the numbers of specific CD8+ T cells within 30 days of virus inoculation.

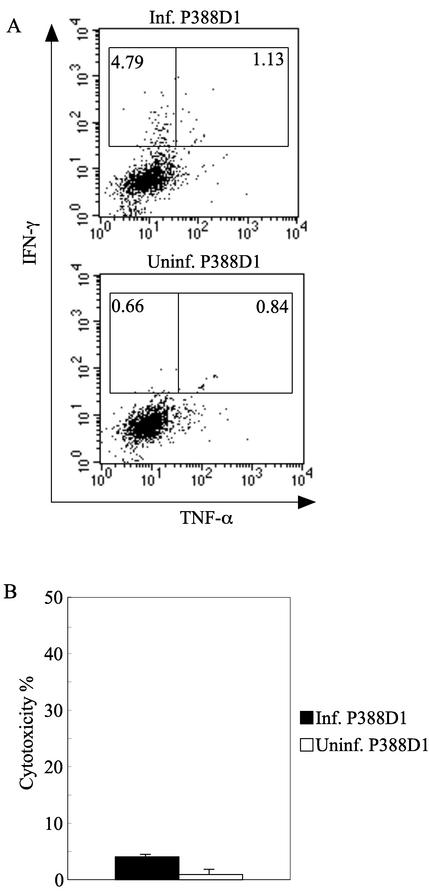

N protein was detected in all mice at day 12 (Fig. 7A). Neutralizing antibodies were found in sera (Fig. 7B) and did not affect the amount of N protein. Next, we attempted to detect virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Although there were no CD8+-T-cell responses until 12 days after inoculation, IFN-γ+ CD8+ cells were detected at 15 days (data not shown). However, the IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells were also detected in a mixture of spleen cells and uninfected P388D1 cells (data not shown). To reduce this nonspecific reaction, we removed adherent cells from among spleen cells, because HTNV-infected adherent cells seemed to play a role as APC. As a result, we succeeded in obtaining an HTNV-specific reaction (Fig. 8). However, these virus-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ produced little TNF-α. In addition, no virus-specific cytotoxicity was observed in vitro. Most of the IFN-γ+ CD8+ cells had disappeared at 18 days (data not shown). Therefore, although HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells were induced in the acute phase in HTNV-infected newborn mice, specific CD8+-T-cell function was impaired and the specific CD8+ T cells were exhausted immediately. Therefore, HTNV did not seem to be eliminated in the acute phase.

FIG. 7.

N protein content and neutralizing antibody titers (NT) in HTNV-infected newborn mice in the acute phase. Within 24 h of birth, newborn mice were inoculated s.c. with 1 NMLD50 of HTNV. Lungs and sera were obtained from the newborn mice at each time point. (A) The N protein content of the lungs was measured by Western blotting. Band density was determined by NIH Image 1.6.1 analysis software. To calculate the density of each point, the median density for newborn mice infected with 1 NMLD50 of HTNV on day 30 was set at 100% as in Fig. 4. (B) FRNTs were carried out using sera, and the neutralizing antibody titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution resulting in a reduction of more than 80% of infected cell foci. The average at each time point is represented as a solid line. Results for each viral dose were obtained in two independent experiments.

FIG. 8.

TNF-α production by IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells and cytotoxic activity of spleen cells obtained from HTNV-infected newborn mice in the acute phase. Spleen cells isolated from HTNV-infected newborn mice (1 NMLD50) at day 15 after virus inoculation were tested for TNF-α production (A) and cytotoxic activity (B). (A) To detect TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells, spleen cells and target cells were cocultured at a ratio of 1:0.5 for 6 h in the presence of brefeldin A and IL-2. IFN-γ+ HTNV-infected P388D1 cells (Inf. P388D1; upper panel) and uninfected P388D1 cells (Uninf. P388D1; lower panel, negative control) were used as target cells. TNF-α production by CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells was detected using flow cytometry. The gates were set for CD8+ T cells, and the numbers are the percentages of TNF-α− IFN-γ+ and TNF-α+ IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells. (B) For the cytotoxic assay, spleen cells were cultured as described in Materials and Methods. The spleen cells were tested using an LDH release cytotoxic assay. HTNV-infected P388D1 cells (positive control) and uninfected P388D1 cells (negative control) were used as target cells. The bars represent the standard deviations. E/T ratio, 20. Data from a representative experiment are shown.

DISCUSSION

Hantaviruses and viruses in the genus Arenavirus have a similar etiology; both persistently infect rodent reservoirs without signs of disease. Immunological characterization of LCMV infection in a mouse model elucidated the fundamental role of cellular immunology in persistent infection. This characteristic may reflect the ultimate principle in host-parasite relationships after coevolution of the parasites with their rodent reservoirs for tens of millions of years (12). However, rodent hantavirus infection is not well characterized due both to the lack of suitable mouse models that represent persistent infection and to the technical difficulties associated with measuring cellular immunology. To examine the relationship between persistent infection and cellular immunity, the present study established methods for measuring levels of virus-specific CD8+ T cells and applied them to a newborn mouse model that we previously reported as a persistent infection model.

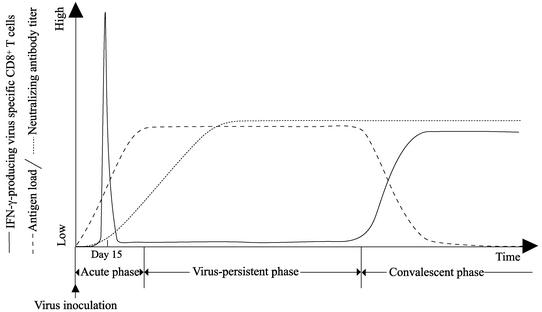

We summarize the fluctuations in the immune responses and virus antigen loads of HTNV-infected newborn mice in Fig. 9. HTNV-infected newborn mice induced IFN-γ-producing virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the acute phase, but TNF-α production and the cytotoxic activity of the cells were impaired in vitro. Moreover, these CD8+ T cells disappeared immediately. The virus antigen loads seemed to increase because of functional impairment of these specific CD8+ T cells. Virus antigen existed in the lungs during the virus-persistent phase without detectable functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells. By contrast, the cytotoxic activity of and TNF-α production by the IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in the convalescent phase were identical to those of virus-specific CD8+ T cells of HTNV-infected adult mice. Virus antigen removal from the lungs accorded with the appearance of functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the convalescent phase. These results suggest that functional cellular immune responses play a key role in the elimination of hantaviruses in mice.

FIG. 9.

Schema of the fluctuation of the numbers of virus-specific CD8+ T cells, neutralizing antibody titers, and antigen loads (amounts of N protein in lungs) in HTNV-infected newborn mice. In the acute phase, IFN-γ-producing virus-specific CD8+ T cells were induced, but TNF-α production and the cytotoxic activity of these CD8+ T cells were impaired in vitro. In the virus-persistent phase, high neutralizing antibody titers were maintained and there were no functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells. In the convalescent phase, functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells appeared and the amounts of N protein decreased.

A similar relationship between virus-specific CD8+ T cells and persistent virus infection has been well studied in persistently LCMV-infected mice. Previous studies have shown that infection of newborn mice with LCMV or infection of adult mice with certain LCMV induces viral persistence without CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. In both LCMV-infected newborn mice and LCMV-infected adult mice, high viral replication rates and widespread infection of many organs and tissues are important for the establishment of persistent infection. In addition, it is known that the virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes of LCMV-infected newborn mice are removed by thymic deletion and those of LCMV-infected adult mice are removed by peripheral deletion, which is called immune exhaustion (4). In our study, a high accumulation of viral antigens was found in lungs from persistently infected newborn mice. Previous studies also showed that HTNV propagates in many organs and tissues of newborn mice (9, 13, 16, 34). In addition, IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells were observed in the acute phase transiently. These findings suggest that HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells are eliminated from newborn mice by immune exhaustion, as in LCMV-infected adult mice.

In this study, we were not able to analyze levels of HTNV-specific CD4+ T cells because we have not yet established a method to measure them. It has been reported that HTNV-infected nude mice have lower antibody responses than HTNV-infected immunocompetent mice (22). By contrast, high neutralizing antibody titers were detected in the sera of HTNV-infected newborn mice in this study. These findings imply that the Th2 response of virus-specific CD4+ T cells is functional. Although the Th1 responses in HTNV-infected newborn mice are unclear, unbalanced Th1 and Th2 responses, as shown in neonatal mice (11), to hantavirus infection might be another potential mechanism for suppressing HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells.

To analyze immune response at the immature stage in this mouse model, we tried to detect virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the acute phase. HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ were induced at day 15 after virus inoculation. However, TNF-α production and the cytotoxic activity of these CD8+ T cells were impaired, and the CD8+ T cells disappeared immediately. Wherry et al. proposed a model of the functional exhaustion of CD8+ T cells (35). They distinguished functional exhaustion from the physical deletion of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. The model considered three kinds of functional exhaustion: “partial exhaustion I,” “partial exhaustion II,” and “full exhaustion.” Although most virus-specific CD8+ T cells at the partial exhaustion I stage could produce IFN-γ, they had almost no ability to produce TNF-α or IL-2 or to lyse target cells. At the partial exhaustion II stage, some IFN-γ-producing virus-specific CD8+ T cells were observed but most of the specific CD8+ T cells were unable to produce IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-2 or to lyse target cells. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells at the full exhaustion stage had completely lost all effector functions. These results suggest that the HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells detected at day 15 were at the partial exhaustion I or partial exhaustion II stage. Subsequently, the HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells might have entered the full exhaustion or physical deletion stage by the persistent phase.

In nature, hantaviruses are maintained in persistently infected rodent reservoirs with high neutralizing antibody levels. The mouse model used in this report had a pathogenesis similar to that of hantavirus-infected natural rodent reservoirs, since both retained virus despite the presence of neutralizing antibodies. In the mouse model, the lack of a virus-specific CD8+-T-cell response was important for hantaviral persistence. These results suggest that hantavirus-infected natural rodent reservoirs also maintain virus persistence due to virus-specific CD8+-T-cell loss.

The high accumulation of viral antigens in cases of persistent infection may also explain part of the mechanism that allows distinct hantaviruses to persist in a single rodent species. In this study, adult mice were transiently infected with HTNV and had a number of HTNV-specific CD8+ T cells without viral accumulation in organs. It is also known that hantavirus can transiently infect nonreservoir adult rodents without viral accumulation. It may be important for maintaining the relationship between distinct hantaviruses and a single rodent species that accumulation of viral antigen is induced in a single rodent species. Thus, HTNV-infected adult and newborn mice are very useful for investigating rodent-hantavirus relationships.

However, the newborn mouse model is different in one way from natural rodent reservoirs. In this study, viruses in newborn mice established persistent infection. In nature, however, vertical transmission to newborn rodents is believed not to occur, because maternal antibodies protect newborn rodents from being infected by a persistently hantavirus-infected mother (3, 5, 8, 19, 40). Therefore, it seems that in nature persistent hantavirus infection is established when adult rodents are infected. Further examination of this discrepancy is necessary. In addition, we have reported that high HTNV replication rates in the brains of newborn mice cause death (9, 38). In this study, roughly 50% of the newborn mice infected with 1 NMLD50 died, while natural rodent reservoirs infected with hantaviruses generally develop asymptomatic infection (18). Moreover, although most of the HTNV-infected newborn mice cleared the virus within 4 months of infection, it is believed that natural rodent reservoirs infected with hantaviruses maintain a lifelong infection. In natural rodent reservoirs, the host might lack hantavirus-specific CD8+ T cells throughout its lifetime. However, mark-recapture studies indicate that some deer mice naturally infected with Sin Nombre virus cleared the virus from their blood within a few months (10). In such deer mice, Sin Nombre virus might have been cleared after the appearance of hantavirus-specific CD8+ T cells, as occurs in HTNV-infected newborn mice. Quasispecies of hantaviruses in naturally infected rodents are thought to be another potential mechanism for persistent hantavirus infection. Persistent infection might be established by mutant viruses that have no epitopes to the virus-specific CD8+ T cells initially induced in rodents.

In conclusion, we showed that viral persistence correlated closely with a lack of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. However, some aspects of the relationship between hantavirus infection and virus-specific CD8+-T-cell responses remain unclear, and further investigation of the hantavirus-induced immune response is necessary.

Acknowledgments

K.A. is a research fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and was supported by JSPS Research Fellowships for Young Scientists. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and the Development of Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Tokyo, Japan.

Textcheck (English consultants) revised the English in the final draft of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman, J. D., P. A. Moss, P. J. Goulder, D. H. Barouch, M. G. McHeyzer-Williams, J. I. Bell, A. J. McMichael, and M. M. Davis. 1996. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274:94-96. (Erratum, 280:1821, 1993.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araki, K., K. Yoshimatsu, M. Ogino, H. Ebihara, A. Lundkvist, H. Kariwa, I. Takashima, and J. Arikawa. 2001. Truncated hantavirus nucleocapsid proteins for serotyping Hantaan, Seoul, and Dobrava hantavirus infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2397-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arikawa, J., M. Ito, J. S. Yao, H. Kariwa, I. Takashima, and N. Hashimoto. 1994. Epizootiological studies of hantavirus infection among urban rats in Hokkaido, Japan: evidences for the persistent infection from the sero-epizootiological surveys and antigenic characterizations of hantavirus isolates. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 56:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrow, P., and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1997. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, p. 593-627. In N. Nathanson (ed.), Viral pathogenesis. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 5.Borucki, M. K., J. D. Boone, J. E. Rowe, M. C. Bohlman, E. A. Kuhn, R. DeBaca, and S. C. St. Jeor. 2000. Role of maternal antibody in natural infection of Peromyscus maniculatus with Sin Nombre virus. J. Virol. 74:2426-2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botten, J., K. Mirowsky, D. Kusewitt, M. Bharadwaj, J. Yee, R. Ricci, R. M. Feddersen, and B. Hjelle. 2000. Experimental infection model for Sin Nombre hantavirus in the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10578-10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butz, E. A., and M. J. Bevan. 1998. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity 8:167-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dohmae, K., U. Koshimizu, and Y. Nishimune. 1993. In utero and mammary transfer of hantavirus antibody from dams to infant rats. Lab. Anim. Sci. 43:557-561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebihara, H., K. Yoshimatsu, M. Ogino, K. Araki, Y. Ami, H. Kariwa, I. Takashima, D. Li, and J. Arikawa. 2000. Pathogenicity of Hantaan virus in newborn mice: genetic reassortant study demonstrating that a single amino acid change in glycoprotein G1 is related to virulence. J. Virol. 74:9245-9255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuer, R., J. D. Boone, D. Netski, S. P. Morzunov, and S. C. St. Jeor. 1999. Temporal and spatial analysis of Sin Nombre virus quasispecies in naturally infected rodents. J. Virol. 73:9544-9554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forsthuber, T., H. C. Yip, and P. V. Lehmann. 1996. Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science 271:1728-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez, J. P., and J. M. Duplantier. 1999. The arenavirus and rodent co-evolution process: a global view of a theory, p. 39-42. In J. F. Saluzzo and B. Doet (ed.), Emergence and control of rodent-borne viral diseases (hantaviral and arenal diseases). Elsevier, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Kim, G. R., and K. T. McKee, Jr. 1985. Pathogenesis of Hantaan virus infection in suckling mice: clinical, virologic, and serologic observations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34:388-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, H. W. 1996. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, p. 253-267. In R. M. Elliott (ed.), The Bunyaviridae. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 15.Lundkvist, A., Y. Cheng, K. B. Sjolander, B. Niklasson, A. Vaheri, and A. Plyusnin. 1997. Cell culture adaptation of Puumala hantavirus changes the infectivity for its natural reservoir, Clethrionomys glareolus, and leads to accumulation of mutants with altered genomic RNA S segment. J. Virol. 71:9515-9523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKee, K. T., Jr., G. R. Kim, D. E. Green, and C. J. Peters. 1985. Hantaan virus infection in suckling mice: virologic and pathologic correlates. J. Med. Virol. 17:107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer, B. J., and C. Schmaljohn. 2000. Accumulation of terminally deleted RNAs may play a role in Seoul virus persistence. J. Virol. 74:1321-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer, B. J., and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2000. Persistent hantavirus infections: characteristics and mechanisms. Trends Microbiol. 8:61-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morita, C., S. Morikawa, K. Sugiyama, T. Komatsu, H. Ueno, and T. Kitamura. 1993. Inability of a strain of Seoul virus to transmit itself vertically in rats. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 46:215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser, J. M., J. D. Altman, and A. E. Lukacher. 2001. Antiviral CD8+ T cell responses in neonatal mice: susceptibility to polyoma virus-induced tumors is associated with lack of cytotoxic function by viral antigen-specific T cells. J. Exp. Med. 193:595-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. J. Sourdive, A. J. Zajac, J. D. Miller, J. Slansky, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura, T., R. Yanagihara, C. J. Gibbs, Jr., H. L. Amyx, and D. C. Gajdusek. 1985. Differential susceptibility and resistance of immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice to fatal Hantaan virus infection. Arch. Virol. 86:109-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichol, S. T. 1999. Genetic analysis of hantaviruses and their host relationships, p. 99-109. In J. F. Saluzzo and B. Doet (ed.), Emergence and control of rodent-borne viral diseases (hantaviral and arenal diseases). Elsevier, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Plyusnin, A., Y. Cheng, H. Lehvaslaiho, and A. Vaheri. 1996. Quasispecies in wild-type tula hantavirus populations. J. Virol. 70:9060-9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plyusnin, A., O. Vapalahti, H. Lankinen, H. Lehvaslaiho, N. Apekina, Y. Myasnikov, H. Kallio-Kokko, H. Henttonen, A. Lundkvist, M. Brummer-Korvenkontio, et al. 1994. Tula virus: a newly detected hantavirus carried by European common voles. J. Virol. 68:7833-7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plyusnin, A., O. Vapalahti, H. Lehvaslaiho, N. Apekina, T. Mikhailova, I. Gavrilovskaya, J. Laakkonen, J. Niemimaa, H. Henttonen, M. Brummer-Korvenkontio, et al. 1995. Genetic variation of wild Puumala viruses within the serotype, local rodent populations and individual animal. Virus Res. 38:25-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarzotti, M., D. S. Robbins, and P. M. Hoffman. 1996. Induction of protective CTL responses in newborn mice by a murine retrovirus. Science 271:1726-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmaljohn, C., and B. Hjelle. 1997. Hantaviruses—a global disease problem. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:95-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmaljohn, C. S. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the L genome segment of Hantaan virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:6728.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmaljohn, C. S., G. B. Jennings, J. Hay, and J. M. Dalrymple. 1986. Coding strategy of the S genome segment of Hantaan virus. Virology 155:633-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmaljohn, C. S., A. L. Schmaljohn, and J. M. Dalrymple. 1987. Hantaan virus M RNA: coding strategy, nucleotide sequence, and gene order. Virology 157:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sjolander, K. B., I. Golovljova, V. Vasilenko, A. Plyusnin, and A. Lundkvist. 2002. Serological divergence of Dobrava and Saaremaa hantaviruses: evidence for two distinct serotypes. Epidemiol. Infect. 128:99-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song, G. 1999. Epidemiological progresses of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China. Chin. Med. J. 112:472-477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura, M., H. Asada, K. Kondo, O. Tanishita, T. Kurata, and K. Yamanishi. 1989. Pathogenesis of Hantaan virus in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 70:2897-2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wherry, E. J., J. N. Blattman, K. Murali-Krishna, R. van der Most, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J. Virol. 77:4911-4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao, J. S., H. Kariwa, I. Takashima, K. Yoshimatsu, J. Arikawa, and N. Hashimoto. 1992. Antibody-dependent enhancement of hantavirus infection in macrophage cell lines. Arch. Virol. 122:107-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoo, Y. C., K. Yoshimatsu, R. Yoshida, M. Tamura, I. Azuma, and J. Arikawa. 1993. Comparison of virulence between Seoul virus strain SR-11 and Hantaan virus strain 76-118 of hantaviruses in newborn mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 37:557-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshimatsu, K., J. Arikawa, S. Ohbora, and C. Itakura. 1997. Hantavirus infection in SCID mice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 59:863-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshimatsu, K., J. Arikawa, R. Yoshida, H. Li, Y. C. Yoo, H. Kariwa, N. Hashimoto, M. Kakinuma, T. Nobunaga, and I. Azuma. 1995. Production of recombinant hantavirus nucleocapsid protein expressed in silkworm larvae and its use as a diagnostic antigen in detecting antibodies in serum from infected rats. Lab. Anim. Sci. 45:641-646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, X. K., I. Takashima, and N. Hashimoto. 1989. Characteristics of passive immunity against hantavirus infection in rats. Arch. Virol. 105:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]