Abstract

A new molecular assay (CytAMP) utilizing isothermal signal-mediated amplification of RNA was evaluated for rapid detection of methicillin (oxacillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The assay targeted the coa (coagulase) and mecA genes, thereby simultaneously identifying S. aureus and methicillin (oxacillin) resistance. Results were obtained in approximately 3.5 h as a color signal in 96-well microtiter plates. The detection limit was between 2 × 105 and 106 CFU/assay, equivalent to 4 × 106 to 2 × 107 CFU/ml in an overnight broth. This level of growth was obtained with an initial inoculum of 10 to 50 CFU. The CytAMP assay and a mecA-femB PCR assay both detected 113 MRSA strains among 396 clinical isolates of bacteria (CytAMP sensitivity and specificity were both 100% relative to those of PCR). Conventional culture detected 109 MRSA strains, but with 19 false-positive and 23 false-negative results relative to both molecular methods. Discrepancies were also observed for 100 enrichment broths containing MRSA screening swabs, with 11 broths culture negative but PCR positive. CytAMP and PCR were more in agreement, but six broths were CytAMP negative and PCR positive. Five of these contained 102 to 105 CFU/assay (below the CytAMP detection limit of 2 × 105 CFU/assay), and the sixth contained 106 CFU/assay. Overall, culture and CytAMP had similar sensitivities and specificities relative to those of PCR, but the CytAMP assay enabled swabs to be analyzed as a batch following overnight incubation in enrichment broth, with results reported before 12 noon the next day.

Strains of methicillin (oxacillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are an increasingly important cause of nosocomial infection and a serious infection control problem in many countries worldwide (7, 8, 17). Identification of MRSA among hospitalized patients, particularly in an intensive-care facility or surgical ward, may warrant immediate patient isolation and occasional ward closure, screening of patient contacts and staff, and stringent decontamination measures. Although S. aureus is not normally a difficult organism to identify by conventional culture techniques, accurate determination of oxacillin resistance in staphylococci is often time-consuming and subject to variations in such factors as inoculum size, incubation time, medium pH, and medium salt concentration (3, 20, 23). Screening for carriers, rather than simply identifying infected patients, has been shown to have a major role in controlling outbreaks of MRSA infection (4, 6), but definitive results from conventional culture and susceptibility testing are generally not available for at least 48 to 72 h, resulting in reduced patient throughput, considerable disruption, and substantial extra costs to host units (15, 22).

In view of the need to provide rapid screening results, several laboratories have focused on the development and use of molecular detection methods for MRSA. PCR-based methods have been used extensively in reference laboratories as the “gold standard” for detecting the mecA gene, which is responsible for oxacillin resistance in staphylococci (2). Several commercial kits are available that successfully identify the mecA gene by a rapid molecular or phenotypic approach in organisms already identified as S. aureus (1), but these generally work only with previously purified cultures. A more promising rapid approach involves PCR-based assays for simultaneous detection of the mecA gene and a gene or DNA sequence specific for S. aureus (9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22). Most of these assays have been targeted to blood cultures already known to contain gram-positive cocci, but a PCR assay that simultaneously detects the mecA gene and the S. aureus-specific femB gene has been used successfully in conjunction with overnight screening swab enrichment broths containing oxacillin (13, 22), and a prototype immunoquantitative PCR that allows rapid detection of MRSA in mixed-flora samples has been described elsewhere (9). However, such assays have not yet gained wide acceptance in routine clinical microbiology laboratories, primarily because of the costs and well-known drawbacks (e.g., potential for amplicon cross-contamination) associated with PCR.

In this report we describe the evaluation of a prototype user-friendly isothermal amplification assay (CytAMP) for the rapid detection of MRSA from patient-screening swabs. The assay detects the coagulase (coa) and mecA genes, thereby simultaneously identifying the presence of S. aureus and methicillin (oxacillin) resistance without the need for isolation of pure cultures and subsequent susceptibility testing. Crucially, the assay can be performed on the open bench with no cross-contamination problems, and it yields colorimetric results that can be measured with a standard plate reader in a conventional 96-well microtiter plate format. There is no requirement for the gel electrophoresis equipment or expensive real-time PCR apparatus associated with other molecular assays for the detection of MRSA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CytAMP assay for MRSA.

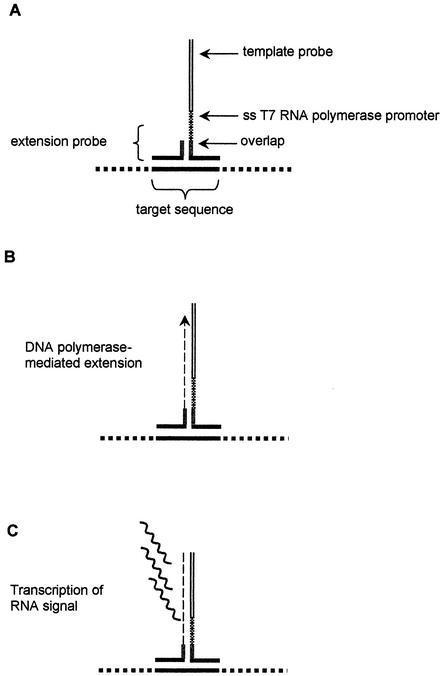

The CytAMP assay is based on isothermal signal-mediated amplification of RNA technology (SMART) (12, 24). Two target-specific single-stranded oligonucleotide probes (the “template” probe and the “extension” probe) are designed so that they can anneal to each other only in the presence of the target, thus forming a structure called a three-way junction (3WJ) (Fig. 1). Following 3WJ formation, DNA polymerase extends the short extension probe so that a single-stranded promoter sequence on the template probe is converted into a functional double-stranded promoter for RNA polymerase, which in turn allows generation of multiple copies of an RNA signal. The RNA signal generated is further increased by additional rounds of extension and transcription (12, 24). Thus, the SMART process is based on signal rather than target amplification. Since the DNA and RNA polymerases function under the same conditions, the entire reaction takes place in a single tube. The RNA signal is detected and quantified by means of an enzyme-linked oligosorbent assay (ELOSA) in which color change is measured with a standard plate reader in a conventional 96-well microtiter plate format (12, 24). The CytAMP MRSA assay detects the coa and mecA genes, thereby simultaneously identifying the presence of S. aureus and methicillin (oxacillin) resistance.

FIG. 1.

Initial stages in the CytAMP assay format. (A) The short extension probe forms a 3WJ in the presence of the target sequence and the template probe. (B) The template probe contains a single-stranded T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence, which is converted to a functional double-stranded promoter by Bst DNA polymerase extension from the extension probe. (C) Multiple copies of an RNA signal sequence are transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase from the template probe. This RNA sequence forms a substrate for additional rounds of extension and transcription in a second reaction that generates an unrelated signal sequence (12, 24). All reactions occur concomitantly in a single microcentrifuge tube.

The initial stage in detection of MRSA by the prototype CytAMP assay kit (Cytocell Ltd., Adderbury, Oxford, United Kingdom) involves lysis of any MRSA cells contained in the sample. For broth samples, 1 ml of broth was centrifuged in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube for 3 min at 12,000 × g. The supernatant was removed by aspiration, and any pelleted cells were lysed by addition of 100 μl of the lysis solution supplied in the kit. For bacteria growing on agar plates, a small loopful of cells was resuspended directly in 100 μl of lysis solution contained in a microcentrifuge tube. In both cases, lysis occurred following incubation on a heat block at 41°C for 10 min. Following incubation, 5 μl of the lysed sample was transferred to a sterile 200-μl microcentrifuge tube, followed by three further incubation steps (performed on hot blocks) of 5 min at 95°C, 60 min at 41°C, and 90 min at 41°C, with sequential addition (according to the manufacturer's instructions) of the preformulated oligonucleotide and enzyme reaction mixes supplied in the kit. The reactions for coa and mecA are performed in separate tubes. End detection was carried out by an ELOSA reaction in a 96-well streptavidin-coated microtiter plate by using the reagents supplied in the kit; it involved incubation at room temperature for 30 min, followed by a further 3 min at room temperature after addition of the substrate. End points for mecA and coa, respectively, were read at 450 nm in a standard plate reader and then compared with results obtained for a substrate blank and the positive and negative controls supplied in the kit. Positive results were defined by a signal/noise ratio of ≥2.0 (as recommended by the manufacturer) but could generally be assessed directly by eye. The presence of MRSA was indicated by positive reactions for both mecA and coa. The total assay time, including the time for sample lysis, was 3.5 to 4 h, depending on the number of samples being handled simultaneously.

Sensitivity and specificity testing.

The specificity of the prototype CytAMP assay was assessed with a collection of 396 clinical isolates supplied by Nottingham Public Health Laboratory and the Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom. These isolates were originally identified using conventional bacteriological tests (e.g., colony appearance, Gram's stain, catalase, DNase, and coagulase tests), combined where necessary with growth on oxacillin resistance screening agar (ORSA; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). In some cases, additional tests were used to confirm identity, including agglutination with a Slidex Staph kit (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), biochemical identification with the API Staph or Vitek system (bioMérieux), and latex agglutination tests for pencillin binding protein PBP2′ (Oxoid). As originally identified by these methods, the collection comprised 109 MRSA strains, 163 methicillin (oxacillin)-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strains, 49 coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS), and 75 other assorted gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. As part of the present study, all isolates were retested with the multiplex mecA-femB PCR test for MRSA described previously (22). To assess the specificity of the CytAMP assay, fresh overnight cultures growing on nutrient agar (Oxoid) were picked off, lysed, and tested in duplicate by the CytAMP assay as described above.

Determination of detection limit.

Twofold dilutions in 5 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid) containing oxacillin (2 μg/ml; Sigma) of a similar overnight broth culture of a standard strain of MRSA were each tested five times by the CytAMP assay as described above. At the same time, 100-μl portions of each broth dilution were spread onto plates of nutrient agar. Average signal/noise ratios were calculated for each dilution and plotted against the viable counts obtained after overnight incubation at 37°C.

Patient-screening samples.

One hundred sets of MRSA screening swabs (usually comprising two to five swabs from different body sites) were received from individual patients hospitalized in University Hospital Nottingham. In United Kingdom hospitals it is common practice to receive swabs from the nose, skin lesions, and other body sites and pool them together in a single enrichment broth (5). This is a cost-effective method where the aim is to determine the presence, rather than the site, of MRSA infection. In this study, each set was pooled into 5 ml of brain heart infusion broth containing 2 μg of oxacillin/ml and incubated statically overnight for 17 h at 30°C. Following incubation, each broth was examined by conventional culture, multiplex PCR, and the CytAMP technique. For conventional culture, 100 μl of each broth was spread onto ORSA, incubated at 37°C, and inspected for dark-blue colonies (presumptive MRSA) after 24 and 48 h. Confirmatory latex agglutination tests for the presence of PBP2′ (Oxoid) and S. aureus-specific proteins (Slidex; bioMérieux) were performed as recommended by the respective manufacturers. Multiplex PCR to simultaneously detect the presence of the mecA gene and the S. aureus-specific femB gene was performed on the overnight enrichment broths as described previously (22). For CytAMP analysis, 1 ml of each broth was centrifuged in a microcentrifuge tube for 3 min at 12,000 × g. The supernatant was then discarded, and the pellet was lysed and analyzed according to the CytAMP method described above.

RESULTS

Sensitivity and specificity of the CytAMP assay.

Table 1 compares the results obtained by conventional culture, the mecA-femB PCR test, and the CytAMP assay. The “gold standard” PCR method detected 111 MRSA isolates among the 396 isolates examined, compared with 113 recognized by CytAMP. These 113 isolates included all 111 isolates detected by PCR. The two discrepant isolates were subsequently also recognized as MRSA by PCR when the lysis method recommended in the CytAMP kit was used instead of the slightly quicker lysis procedure normally employed in the PCR test (22). Thus, in terms of detecting MRSA, the two molecular methods were ultimately in agreement that there were 113 MRSA isolates in the collection (giving a CytAMP sensitivity and specificity of 100% relative to PCR). A few minor discrepancies between CytAMP and PCR were observed for the non-MRSA isolates, with one isolate yielding a false-negative mecA result and three isolates yielding false-positive coa results (relative to femB results). Six isolates (Table 1) were identified by CytAMP as S. aureus on the basis of a positive coa signal but were not so identified by PCR following lack of femB amplification. Of these, three were negative by Slidex latex agglutination, one was consistently negative for femB amplification, and two were PCR lysis failures. The conventional cultural identification methods originally used to identify the isolates suggested that there were 109 MRSA isolates in the collection, but this result concealed significant discrepancies with molecular identification, with 19 MRSA false positives and 23 MRSA false negatives (i.e., isolates that failed to yield dark-blue colonies on ORSA), of which 14 were identified by conventional culture as “borderline oxacillin-resistant S. aureus” (BORSA).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of results obtained by conventional culture, mecA-femB PCR assays, and CytAMP assays for 396 bacterial isolates

| Identification | No. of isolates identified by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | PCR | CytAMP | |

| S. aureus | |||

| MRSA | 109a | 111b | 113c |

| MSSA | 163d | 164 | 168 |

| CNS | 49 | 52 | 51 |

| Other species | 65 | 66 | 63 |

| Unidentified | 10 | 3 | 1 |

Includes 19 isolates that were not identified as MRSA by either PCR or CytAMP.

Two additional isolates were identified as MRSA by PCR when the CytAMP lysis method was used.

All 113 isolates were also identified as MRSA by PCR when the CytAMP lysis method was used.

Includes 23 isolates that were identified as MRSA by PCR and CytAMP; 14 of these were considered to have borderline sensitivity following culture.

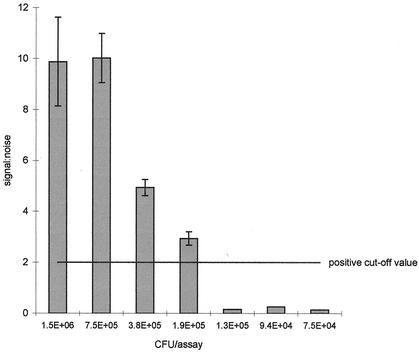

Detection limit of the CytAMP assay.

Figure 2 illustrates the signal/noise ratios for mecA obtained in a typical experiment with five duplicate assays and decreasing numbers of MRSA cells in each sample. Signal/noise ratios for coa were always higher than those obtained for mecA by a factor of 2 to 3. Although the reason for this finding is not clear, it is probably related to the efficiency of 3WJ formation being affected by the precise sequence of the probe-binding site. Minor variations were observed between experiments, but based on the requirement for both mecA and coa to yield a positive result, the limit of detection for MRSA was between 2 × 105 and 106 CFU/assay, equivalent to 4 × 106 to 2 × 107 CFU/ml in the original enrichment broth. In trial experiments with enrichment broth containing oxacillin, this level of growth was achieved with an initial inoculum of 10 to 50 CFU, followed by static growth for 17 h at 30°C.

FIG. 2.

Signal/noise ratios for mecA obtained in a typical experiment with five duplicate assays and decreasing numbers of MRSA in each sample. Error bars, standard errors. The positive cutoff value of 2.0 was that recommended for the prototype assay by the manufacturer.

Evaluation of the CytAMP assay with patient-screening swabs.

When 100 enrichment broths containing sets of screening swabs from individual patients were tested, the presence of MRSA was detected in 19, 24, and 31 enrichment broths by CytAMP, conventional culture, and mecA-femB PCR, respectively. There is no gold standard for the detection of MRSA in this application, and discrepancies were observed among the three methods. On the basis of the detection limit results described above, it was expected that the CytAMP assay would be less sensitive than PCR and culture (both theoretically capable of detecting 1 CFU). Six enrichment broths were negative by CytAMP but positive by both PCR and culture. Five of these contained the equivalent of 102 to 105 CFU/assay (below the predicted detection limit of 2 × 105 CFU/assay for CytAMP), and the sixth contained the equivalent of 106 CFU/assay. However, 11 broths were negative by culture (i.e., they failed to yield blue colonies on ORSA) and positive by PCR; of these 11, 4 were also positive by CytAMP. Seven broths were positive only by PCR (i.e., they were negative by CytAMP and culture), and this is reflected in the sensitivity figures shown in the overall comparison of the CytAMP assay and conventional culture against mecA-femB PCR (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of CytAMP and conventional culture with mecA-femB PCR for the detection of MRSA

| Test being evaluated | Comparison with PCRa

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | |||

| CytAMP | 94.7 | 84.0 | 58.1 | 98.6 | ||

| Culture | 83.3 | 85.5 | 64.5 | 94.2 | ||

All values are percentages. PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

DISCUSSION

Although detection of MRSA in routine clinical specimens is important for identifying individual infected patients, screening of patient contacts and staff for MRSA carriage is considered to be one of the most important measures necessary for prevention and control of MRSA outbreaks (6). It has already been shown in Spain that it is possible to reduce the number of infections with MRSA, and the associated mortality, by switching to a control strategy involving identification and treatment of carriers (4). Conventional microbiological culture and susceptibility testing methods require 48 to 72 h to screen patients and staff for MRSA carriage, and even then, as reported in this study and previously (3, 10, 20, 22, 23), routine diagnostic laboratories often encounter difficulties in identifying MRSA correctly. For this reason, there has been increasing interest in the use of rapid and specific molecular identification methods for this purpose. To our knowledge, the comparatively low numbers of MRSA bacteria present on patient-screening swabs have so far precluded any direct application of molecular methods to such specimens, but a 3-h PCR-based method has been used successfully in conjunction with an overnight broth enrichment step to generate sensitive and specific results within 20 h of the arrival of screening swabs in the laboratory (i.e., by 12 noon the next day) (13, 22). Unfortunately, PCR is a relatively high cost method that requires dedicated accommodation and apparatus and is not suitable for performing on the open bench in a busy routine diagnostic laboratory. In an attempt to avoid these difficulties, the work described in this paper compared conventional culture and PCR with a novel isothermal signal amplification method that generated colorimetric results in a conventional 96-well microtiter plate format.

Overall, the novel CytAMP assay evaluated in the present work, when used to analyze 396 previously isolated pure bacterial cultures, had a specificity comparable to that of PCR and considerably better than that of conventional culture-based identification. Both the PCR and CytAMP assays recognize two gene targets—one diagnostic of methicillin (oxacillin) resistance and the other diagnostic for S. aureus—and a few minor discrepancies were observed between CytAMP and PCR for the non-MRSA isolates. However, these two molecular methods were in agreement on the 113 MRSA isolates contained in the collection. In contrast, the conventional culture-based method yielded a significant number of false-positive and false-negative MRSA identifications compared with PCR, and there were particular problems with isolates identified by conventional culture as BORSA.

Investigation of patient-screening swabs presents a different set of challenges in that there is the potential for mixed enrichment cultures comprising, e.g., MSSA and mecA+ CNS. Such a combination would generate both of the specific amplification products, one from each component organism in the broth, resulting in a false-positive result for MRSA. However, previous studies with PCR-based methods (13, 22) have demonstrated that this scenario can be prevented by the addition of oxacillin to the enrichment broth, thereby inhibiting the growth of any MSSA present on the swabs, so that the S. aureus-specific target would not be detected. For this reason, oxacillin was also added to the initial enrichment broths used for the CytAMP assays. Any remaining false-positive results should be picked up during repeat patient screens but would be an acceptable outcome on a rare basis in view of the potential economic advantages of reliably screening out noncolonized patients, thereby unblocking beds as rapidly as possible. There is no recognized gold standard for the detection of MRSA from patient-screening swabs, but the CytAMP assay performed similarly to culture in comparison with PCR. Although the apparent sensitivities of both the CytAMP assay and culture were lower than that of PCR, it is worth noting that PCR is known to yield apparent false-positive results in this application, presumably resulting from the presence of dead cells or cross-contamination (22). However, six enrichment broths were CytAMP negative but positive by both culture and PCR. Each of these broths contained low numbers of CFU, probably originating from <10 CFU on the patient swabs. Therefore, inhibition of the CytAMP assay by broth contents did not seem to be a major factor contributing to these false-negative results. Further long-term studies are required to assess whether such low MRSA numbers are obtained from patients with long-term colonization or whether they simply indicate short-term transient carriage. It would also be advantageous to include an inhibition control in a production version of the kit.

An important question concerns the cost-effectiveness of rapid screening programs. Identification of MRSA normally results in immediate isolation of the affected patient, screening and cohorting of patient contacts and staff, and appropriate cleaning measures or ward closures. These actions inevitably result in reduced patient throughput; considerable disruption for staff, patients, and their families; and substantial extra costs for host units. Such costs include those associated with staff and patient screening, prolonged hospital stays, ward closures, disinfection and cleaning, protective clothing, redeployment of staff, and additional communication costs. Although difficult to quantify, it has been estimated that the attributable patient-specific costs of MRSA associated with excess hospitalization and concurrent treatment in Canadian hospitals alone amount to $42 million to $59 million each year (15). The prototype CytAMP assay is not yet commercially available but is cheaper to formulate (approximately $5 per assay) than standard PCR-based assays. In this context, the additional expense of a rapid MRSA screening program would quickly become cost-effective if a relatively small reduction in MRSA infection rates were achieved.

In conclusion, the prototype CytAMP assay was found to be user-friendly for non-molecular biologists and offers an attractive alternative to conventional culture or PCR for the rapid and specific identification of MRSA in routine clinical microbiology laboratories. A significant advantage is that the final product of the assay cannot be used to form the initial 3WJ. Therefore, the problem of cross-contamination of amplicons that is often associated with PCR is avoided. Some minor enhancement of the sensitivity of the prototype assay would be desirable, but the assay lends itself well to incorporation into the work flow of the average clinical microbiology laboratory, so that patient swabs arriving in the laboratory during the day can be analyzed as a batch (total hands-on time, approximately 1.5 h) following overnight incubation in enrichment broth, with results reported to the hospital ward before 12 noon the next day. The amplification steps of the prototype assay take place in a single microcentrifuge tube, but it should be possible to develop a single-well microtiter plate assay using the same format. Interestingly, since the signal amplification and detection steps are “universal,” the assay format is adaptable to the detection of any microbiological target provided that appropriate target-specific oligonucleotides capable of forming an initial 3WJ can be designed.

Acknowledgments

Alec Bowden, Samantha Ho, Graham Mock, Clint Pereira, Emma Robinson, Suzanne Rush, and Joanna Thomas are thanked for their roles in the development of the prototype assay format.

This work was funded by Cytocell Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbique, J., K. Forward, D. Haldane, and R. Davidson. 2001. Comparison of the Velogene rapid MRSA identification assay, Denka MRSA-screen assay, and BBL Crystal MRSA ID system for rapid identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 40:5-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bignardi, G. E., N. Woodford, A. Chapman, A. P. Johnson, and D. C. E. Speller. 1996. Detection of the mec-A gene and phenotypic detection of resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates with borderline or low-level methicillin resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 37:53-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, D. F. J. 2001. Detection of methicillin/oxacillin resistance in staphylococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48(Suppl. 1):65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coello, R., J. Jiminez, M. Garciá, P. Arroyo, D. Minguez, C. Fernández, F. Cruzet, and C. Gaspar. 1994. Prospective study of infection, colonization and carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an outbreak affecting 990 patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:74-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combined Working Party of the British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the Hospital Infection Society and the Infection Control Nurses Association. 1998. Revised guidelines for the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in hospitals. J. Hosp. Infect. 39:253-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cookson, B. 1997. Is it time to stop searching for MRSA? Screening is still important. Br. Med. J. 314:664-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diekema, D. J., M. A. Pfaller, F. J. Schmitz, J. Smayevsky, J. Bell, R. N. Jones, M. Beach, and the SENTRY Participants Group. 2001. Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific Region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997-1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 2):S114-S132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fluit, A. C., C. L. C. Wielders, J. Verhoef, and F. J. Schmitz. 2001. Epidemiology and susceptibility of 3,051 Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 25 university hospitals participating in the European SENTRY study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3727-3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francois, P., D. Pittet, M. Bento, B. Pepey, P. Vaudaux, D. Lew, and J. Schrenzel. 2003. Rapid detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from sterile or nonsterile clinical samples by a new molecular assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:254-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frebourg, N. B., D. Nouet, L. Lemée, E. Martin, and J.-F. Lemeland. 1998. Comparison of ATB Staph, Rapid ATB Staph, Vitek, and E-test methods for detection of oxacillin heteroresistance in staphylococci possessing mecA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:52-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grisold, A. J., E. Leitner, G. Mühlbauer, E. Marth, and H. K. Kessler. 2002. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and simultaneous confirmation by automated nucleic acid extraction and real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2392-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall, M. J., S. D. Wharam, A. Weston, D. L. N. Cardy, and W. H. Wilson. 2002. Use of signal-mediated amplification of RNA technology (SMART) to detect marine cyanophage DNA. BioTechniques 32:604-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonas, D., H. Grundmann, D. Hartung, F. D. Daschner, and K. J. Towner. 1999. Evaluation of the mecA femB duplex PCR for detection of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:643-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kearns, A. M., P. R. Seiders, J. Wheeler, R. Freeman, and M. Steward. 1999. Rapid detection of methicillin-resistant staphylococci by multiplex PCR. J. Hosp. Infect. 43:33-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, T., P. I. Oh, and A. E. Simor. 2001. The economic impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canadian hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 22:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lem, P., J. Spiegelman, B. Toye, and K. Ramotar. 2001. Direct detection of mecA, nuc and 16S rRNA genes in BacT/ALERT blood culture bottles. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 41:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowy, F. D. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:520-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maes, N., J. Magdalena, S. Rottiers, Y. De Gheldre, and M. J. Struelens. 2002. Evaluation of a triplex PCR assay to discriminate Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci and determine methicillin resistance from blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1514-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrestha, N. K., M. J. Tuohy, G. S. Hall, C. M. Isada, and G. W. Procop. 2002. Rapid identification of Staphylococcus aureus and the mecA gene from BacT/ALERT blood culture bottles by using the LightCycler system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2659-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smyth, R. W., G. Kahlmeter, B. Liljequist, and B. Hoffman. 2001. Methods for identifying methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 48:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan, T. Y., S. Corden, R. Barnes, and B. Cookson. 2001. Rapid identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from positive blood cultures by real-time fluorescence PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4529-4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Towner, K. J., D. C. S. Talbot, R. Curran, C. A. Webster, and H. Humphreys. 1998. Development and evaluation of a PCR-based immunoassay for the rapid detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:607-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallet, F., M. Roussel-Delvallez, and R. J. Courcol. 1996. Choice of a routine method for detecting methicillin-resistance in staphylococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 37:901-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wharam, S. D., P. Marsh, J. S. Lloyd, T. D. Ray, G. A. Mock, R. Assenberg, J. E. McPhee, P. Brown, A. Weston, and D. L. N. Cardy. 2001. Specific detection of DNA and RNA targets using a novel isothermal nucleic acid amplification assay based on the formation of a three-way junction structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e54. [Online.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]