Abstract

The fungal load in organs and blood of susceptible and resistant mice infected with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis was quantitated by using the optical brightener Blankophor and compared with CFU counts. Fluorescent staining of fungal cells proved to be a quick and easy procedure, suitable for evaluation of paracoccidioidomycotic infection.

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis is a thermally dimorphic fungus which causes paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), the most prevalent systemic mycosis in Latin America. Experimental murine models of PCM infection have been used for the study of several parameters of host defense and of virulence of different P. brasiliensis isolates. One isogenic murine model previously described by our group (4) mimics the severe and the mild chronic forms of the human disease.

The severity of PCM in experimental models is usually evaluated by the determination of P. brasiliensis dissemination by counting CFU of macerated organs seeded in semisolid modified brain heart infusion agar medium (5, 16). Serological tests are also commonly used for the follow-up of experimental and human PCM as well as for evaluation of treatment efficacy, in spite of some disadvantages like cross-reactivity (1, 12). The detection of circulating P. brasiliensis antigens (antigenemia) has sometimes been used for clinical diagnosis and follow-up of patients during and after antifungal therapies in parallel with serological reactions for antibody detection, despite serious limitations such as low sensitivity and variable results (7, 8).

Fluorescent staining techniques have allowed the study of fungal cell viability in experimental infection (3), as well as the detection of fungi in clinical and experimental specimens (16).Calcofluor {4,4′-bis[2-di(2-hydroxyethyl)amino-4-phenylami-no-1,3,5-triazine-6-ylamino]-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid, sodium salt} and Blankophor {4,4′-bis[(4-anilino-6-substituted 1,3,5-triazine-2-yl)amino]stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid} are fluorescent dyes of the diaminostilbene type that have high affinity for beta-glycosidically linked polysaccharides, such as chitin and glucan, present in the fungal cell wall. In human infections, Blankophor has been used for the diagnosis of deep mycoses and is suitable for identification of fungal cells in tissue sections, body fluids, and smears (15), as well as for examination of skin, nail scrapings, and hair to confirm the presence of cutaneous mycoses (13). Fungi have been localized in macerated organs in in vitro and in vivo experimental models (15, 16); however, there is no reference in the literature to Blankophor dye being employed to quantify fungal infection. Quantitation of fungal cells in experimental histoplasmosis and candidiasis was evaluated in another study with Calcofluor White staining by a flow cytometry method (6).

In the present work, we evaluated the fungal load in organs and blood of resistant (A/J) and susceptible (B10.A) female mice throughout intraperitoneal infection (4) with the highly virulent P. brasiliensis isolate Pb18 (10) and established comparative parameters between the Blankophor staining and the CFU counting techniques.

Spleen, omentum, pancreas, and heparinized blood were collected under sterile conditions from mice killed 15, 30, 90, and 120 days after infection with 5 × 106 P. brasiliensis cells that were kept in culture and prepared for inoculation as previously described (19). Each sample was divided, and fungal load was evaluated by both techniques, Blankophor staining and CFU counts. The in vitro and in vivo assays with Blankophor were compared, and the in vitro technique, which yielded the best results, was used in all experiments, according to the method described by other authors (16) with some modifications. Briefly, the organs were macerated in 3 ml of an aqueous solution of Blankophor P Fluessig (Bayer AG) at a concentration of 0.1% (wt/vol) in 20% (wt/vol) aqueous potassium hydroxide. After maceration, the samples were transferred to polypropylene tubes and incubated for 3 to 4 h at 37°C. The blood samples were incubated with the Blankophor solution (at a 1:3 dilution) for 3 to 4 h at 37°C. Stained specimens were observed in hemocytometer chambers (Neubauer), and the fungal cells were counted in all fields by using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMLB), with an excitation wavelength below 400 nm and a barrier filter at a 420-nm wavelength. Results were expressed as mean numbers ± standard errors (SEs) of P. brasiliensis cells with characteristic morphology per milliliter. For CFU counts, the organs were ground with a tissue grinder in 5 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and transferred to polypropylene vials. Homogenates were centrifuged in an Incibrás Spin VI instrument three times at 3,000 rpm for 5 min each and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. This resuspended sediment was used to obtain 1/5, 1/10, 1/20, and 1/50 dilutions in PBS. One hundred microliters of each dilution was plated into petri dishes containing semisolid modified brain heart infusion agar medium supplemented with 4% (vol/vol) normal horse serum; 5% Pb192 culture filtrate as a source of growth-promoting factor (18); and 1% antibiotic (streptomycin-penicillin). The plates were incubated at 35 to 37°C, and colonies were counted over 14 days (until no increase in fungal growth counts was observed) by using a stereoscopic microscope (Hund Wetzlar). The results were expressed as mean (±SE) CFU per milliliter.

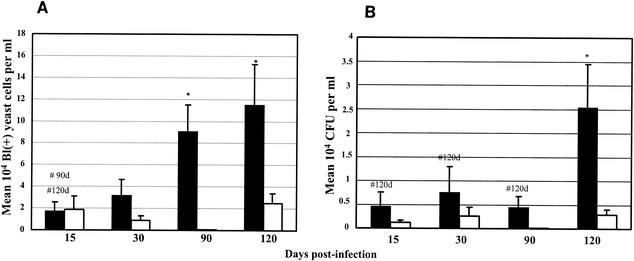

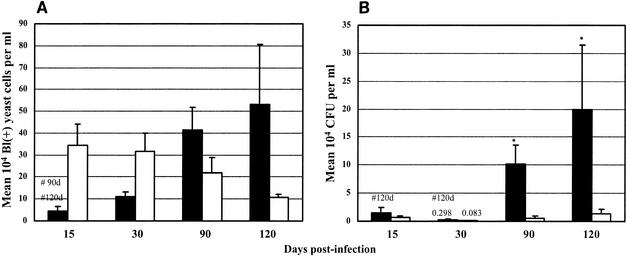

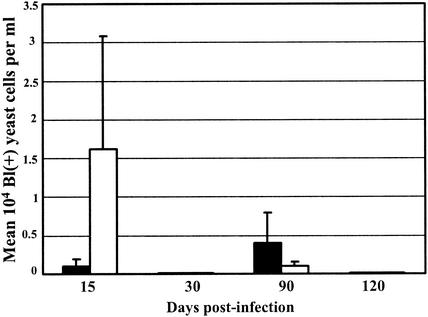

Comparing the presence of P. brasiliensis in the spleens of susceptible and of resistant mice in the course of the infection, by the Blankophor assay, we found similar numbers of fungal cells after 15 days of infection and higher numbers of fungi after 30, 90, and 120 days of infection in the susceptible mice than in the resistant mice (Fig. 1A). Similar comparison by CFU counts showed higher numbers of viable fungal cells in the spleens of susceptible mice than in those of resistant mice at all stages of the infection (Fig. 1B). Both methods showed progressive increases in fungal numbers in the susceptible strain and constant low numbers in the resistant strain. In the omentum and pancreas, the number of fungal cells detected by Blankophor was lower in susceptible mice than in the resistant mice at 15 and 30 days of infection but higher in susceptible mice at later phases of the disease (90 and 120 days postinfection) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the CFU recovered from the omentum and pancreas were higher in susceptible mice than in resistant mice throughout the infection (Fig. 2B). In the blood, it was not possible to detect any P. brasiliensis cells by CFU counting, confirming previous data. The Blankophor assay, on the other hand, allowed the observation and quantitation of P. brasiliensis cells at both 15 and 90 days postinfection. In the early phase of infection (15 days), a larger number of fungal cells were detected in resistant mice than in susceptible mice, and at a later stage (90 days), the numbers of P. brasiliensis cells were much higher in susceptible than in resistant mice (Fig. 3). At 30 and 120 days of infection, fungal cells in the blood were not observed in either strain of mice.

FIG. 1.

Quantitation of fungal load in spleens of susceptible (B10.A, black bars) and resistant (A/J, white bars) mice at 15, 30, 90, and 120 days postinfection with P. brasiliensis isolate Pb18. (A) Blankophor (Bl) staining. The results were expressed as mean numbers ± SEs (104) of fluorescent typical fungal cells per milliliter of sample. (B) CFU counts. The results were expressed as mean CFU ± SEs (104) of viable fungal cells per milliliter of sample. #, significantly different from B10.A mice throughout the infection (P < 0.05); *, significant difference between B10.A and A/J mice (P < 0.05), both by the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test.

FIG. 2.

Quantitation of fungal load in omentum and pancreas of susceptible (B10.A, black bars) and resistant (A/J, white bars) mice at 15, 30, 90, and 120 days postinfection with P. brasiliensis isolate Pb18. (A) Blankophor (Bl) staining. The results were expressed as mean numbers ± SEs (104) of fluorescent typical fungal cells per milliliter of sample. (B) CFU counts. The results were expressed as mean CFU ± SEs (104) of viable fungal cells per milliliter of sample. #, significantly different from B10.A mice throughout the infection (P < 0.05); *, significant difference between B10.A and A/J mice (P < 0.05), both by the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test.

FIG. 3.

Quantitation of fungal load in blood of susceptible (B10.A, black bars) and resistant (A/J, white bars) mice infected with Pb18 at 15, 30, 90, and 120 days postinfection by Blankophor (Bl) staining. The results were expressed as mean numbers ± SEs (104) of fluorescent typical fungal cells per milliliter of sample.

The techniques yielded comparable results regarding P. brasiliensis dissemination in the spleens of infected mice. A significant progressive increase of fungal cell numbers was observed from early to late phases of the disease in susceptible mice, in parallel with the infection, being significant between 15 and 90 days and between 15 and 120 days of infection by the Blankophor staining (Fig. 1A) and at 15, 30, and 90 days compared to 120 days by the CFU counts (Fig. 1B). Blankophor staining appeared to be more sensitive than growth, in that cells were detected earlier with the fluorescent dye than CFU were by the CFU assay. Significant differences in the numbers of fungal cells of susceptible and resistant mice were found after 90 and 120 days by Blankophor and at 120 days by CFU assays (Fig. 1). Again, Blankophor staining was more sensitive, because it allowed earlier discrimination between fungal load in resistant and susceptible mice than did the CFU counts. Neither technique demonstrated an increase in the numbers of fungal cells from the spleens of resistant mice throughout the infection.

In omentum and pancreas, both techniques detected a progressive increase in P. brasiliensis cell numbers with the length of infection only in susceptible mice (B10.A). Significant differences were found between 15 and 90 days and between 15 and 120 days of infection by the Blankophor assay (Fig. 2A), and between 15 and 120 days, as well as between 30 and 120 days, of infection by CFU counts (Fig. 2B). When fungal load was compared between the mouse strains, higher numbers of P. brasiliensis cells were detected in B10.A mice than in A/J mice after 90 and 120 days of infection by either the Blankophor or the CFU method. Statistically significant results were obtained only at 90 and 120 days postinfection by the CFU technique.

In the blood, P. brasiliensis cells with good morphology were found at 15 and 90 days of infection in both mouse strains only by Blankophor staining (Fig. 3). These results are very interesting, because the fungal cells were not detected by CFU counts in the present work and in all our previous experience. Intraperitoneal inoculation of virulent P. brasiliensis into susceptible B10.A mice resulted in dissemination of viable fungal cells to various organs such as the spleen, omentum, pancreas, liver, and lungs (19). When macrophages from mice of this strain were blocked, viable fungi also reached the myocardium (11). In the kidneys and brains of nude mice similarly intraperitoneally infected, viable P. brasiliensis cells were detected (2). However, attempts at isolation of viable P. brasiliensis from the blood of such animals have been unsuccessful (2, 11, 17, 19). To date, positive culture of P. brasiliensis from blood has been achieved only with intravenously inoculated animals (17). Unlike the other major fungal pathogens (Candida albicans, Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Cryptococcus neoformans), P. brasiliensis has not been routinely isolated from the blood of human patients, except for the occasional isolation from the blood of an AIDS patient (9, 14, 17, 20).

It must be considered, however, that Blankophor staining detects both viable and dead fungal cells, while plate counts detect only viable fungi. Although in this study P. brasiliensis inoculation was done intraperitoneally, fungal cells were detected in the spleen, omentum, and pancreas, suggesting hematogenous dissemination. However, isolation of P. brasiliensis from blood is not the most important aspect of fungal dissemination studies, since the fungal cells also reach various organs and tissues via the lymphatic system.

We report herein the first use of Blankophor dye for detection of P. brasiliensis cells and assessment of fungal load in an experimental model of PCM. The overall sensitivity of Blankophor staining was concordant with that of plate counting, in that mice susceptible to PCM had increasing numbers of fungal cells over time, while resistant mouse strains showed no appreciable increase. Thus, the Blankophor stain has the potential to serve as the basis of a direct, rapid, and reproducible method that would be an alternative to standard plate counting of fungi for the study of experimental PCM as well as for the differentiation of highly susceptible and resistant animal strains.

Acknowledgments

Blankophor P (dry compound) was kindly provided by R. Rüchel (Institute of Hygiene of the University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany). We are grateful to C. S. Cunha and R. S. Oliveira for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grant number 00/10647-1) and Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq) (grant number 350527/95-4).

REFERENCES

- 1.Biagioni, L., M. J. Souza, L. G. Chamma, R. P. Mendes, S. A. Marques, N. G. S. Mota, and M. Franco. 1984. Serology of paracoccidioidomycosis. II. Correlation between class-specific antibodies and clinical forms of the disease. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 78:617-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burger, E., C. C. A. Vaz, A. Sano, V. L. G. Calich, L. M. Singer-Vermes, C. F. Xidieh, S. S. Kashino, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 1996. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection in nude mice: studies with isolates differing in virulence and definition of their T cell-dependent and T cell-independent components. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 55:391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calich, V. L. G., A. Purchio, and C. R. Paula. 1979. A new fluorescent viability test for fungi cells. Mycopathologia 66:175-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calich, V. L. G., L. M. Singer-Vermes, A. M. Siqueira, and E. Burger. 1985. Susceptibility and resistance of inbred mice to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 66:585-594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castañeda, E., E. Brummer, A. M. Perlman, J. G. McEwen, and D. A. Stevens. 1988. A culture medium for Paracoccidioides brasiliensis with high plating efficiency, and the effect of siderophores. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 26:351-358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, W. L., H. C. van der Heyde, and B. S. Klein. 1998. Flow cytometric quantitation of yeast: a novel technique for use in animal model work and in vitro immunologic assays. J. Immunol. Methods 211:51-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freitas da Silva, G., and M. C. Roque-Barreira. 1992. Antigenemia in paracoccidioidomycosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:381-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gómez, B. L., I. Figueiroa, A. J. Hamilton, S. Diez, M. Rojas, A. M. Tobón, R. J. Hay, and A. Restrepo. 1998. Antigenemia in patients with paracoccidioidomycosis: detection of the 87-kilodalton determinant during and after antifungal therapy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3309-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadad, D. J., M. D. Pieres, T. C. Petry, S. F. Orozco, M. D. Melhem, R. A. Paes, and M. J. Gianini. 1992. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (Lutz, 1908) isolated by hemoculture in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 34:565-567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashino, S. S., V. L. G. Calich, E. Burger, and L. M. Singer-Vermes. 1985. In vivo and in vitro characteristics of six Paracoccidioides brasiliensis strains. Mycopathologia 92:173-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashino, S. S., R. A. Fazioli, M. Moscardi-Bacchi, M. Franco, L. M. Singer-Vermes, E. Burger, and V. L. G. Calich. 1995. Effect of macrophage blockade on the resistance of inbred mice to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection. Mycopathologia 130:131-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendes-Giannini, M. J. S., G. B. Del Negro, and A. M. Siqueira. 1994. Serodiagnosis, p. 345-363. In M. Franco, C. Da Silva Lacaz, A. Restrepo, and G. del Negro (ed.), Paracoccidioidomycosis. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 13.Monod, M., S. Jaccoud, R. Stirnimann, R. Anex, F. Villa, S. Balmer, and R. Panizzon. 2000. Economical microscope configuration for direct mycological examination with fluorescence in dermatology. Dermatology 201:246-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Procop, G. W., F. R. Cockerill III, E. A. Vetter, W. S. Harmsen, J. G. Hughes, and G. D. Roberts. 2000. Performance of five agar media for recovery of fungi from Isolator blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3827-3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rüchel, R., and S. Margraf. 1993. Rapid microscopical diagnosis of deep-seated mycoses following maceration of fresh specimens and staining with optical brighteners. Mycoses 36:239-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rüchel, R., M. Schaffrinski, K. R. Seshan, and G. T. Cole. 2000. Vital staining of fungal elements in deep-seated mycotic lesions during experimental murine mycoses using the parenterally applied optical brightener Blankophor. Med. Mycol. 38:231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sano, A., M. Miyaji, and K. Nishimura. 1992. Studies on the relationship between the estrous cycle of BALB/c mice and their resistance to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection. Mycopathologia 119:141-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer-Vermes, L. M., M. C. Ciavaglia, S. S. Kashino, E. Burger, and V. L. G. Calich. 1992. The source of the growth-promoting factor(s) affects the plating efficiency of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 30:261-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer-Vermes, L. M., C. B. Caldeira, E. Burger, and V. L. G. Calich. 1993. Experimental murine paracoccidioidomycosis: relationship among dissemination of the infection, humoral and cellular immune responses. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 94:75-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vetter, E., A. Torgerson, A. Feuker, J. Hughes, S. Harmsen, C. Schleck, C. Horstmeier, G. Roberts, and F. Cockerill III. 2001. Comparison of the BACTEC MYCO/F lytic bottle to the Isolator tube, BACTEC Plus Aerobic F/Bottle, and BACTEC Anaerobic Lytic/10 bottle and comparison of the BACTEC Plus Aerobic F/Bottle to the Isolator tube for recovery of bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi from blood. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4380-4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]