Abstract

Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates were obtained from eight patients in two hospitals in Curitiba, Brazil. The isolates were multiresistant, belonged to a single strain, and produced the OXA-23 carbapenemase. Treatment options were limited, although the isolates were susceptible to polymyxin B in vitro. The strain contributed to the deaths of five patients.

Acinetobacter spp. are important opportunistic pathogens, and Acinetobacter baumannii is the species predominantly found in infections. Virtually any body site can be affected in compromised patients, but the organism is particularly associated with nosocomial invasion of burn wounds, pneumonia, bacteremia, postneurosurgical meningitis, and infections of the urinary tract (3). Treatment is often complicated by multiresistance. Until the early 1970s, nosocomial Acinetobacter infections were successfully treated with gentamicin, minocycline, nalidixic acid, ampicillins, or carbenicillin (3). Since then, there has been a steady increase in the prevalence of resistance, which has compromised penicillins, aminoglycosides, expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, and more recently, fluoroquinolones (7). Carbapenems have become the drugs of choice against Acinetobacter infections in many centers but are slowly being compromised by the emergence of carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases of molecular classes B and D (11). Class B carbapenemases found so far in acinetobacters include various IMP and VIM types; class D enzymes include members of the OXA-23- and OXA-24-related families and various unsequenced types (13).

In 1999, eight carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates were cultured from three patients at the Hospital Universitário Evangélico de Curitiba (HUEC) and from five patients at the Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná (HC). HC and HUEC are tertiary-care teaching hospitals with 635 and 600 beds, respectively; both are in Curitiba, Brazil. The ages of the eight affected patients ranged from 19 to 80 years, and the sites of infection were the respiratory tract (five patients, with one judged to be only colonized), blood (one patient), bone (one patient), and a surgical wound (one patient). All of the patients were mechanically ventilated. The major reason for hospital admission was community-acquired pneumonia, but encephalopathy, pancreatitis, osteomyelitis, neurological disorders, lung cancer, and cerebral hemorrhage were also diagnosed in various patients (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Case histories of patients carrying OXA-23-producing A. baumannii in HUEC and HC

| Hospital | Isolate designation | Age (yr) | Underlying diagnosis | Infection site | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUEC | 1 | 54 | Encephalopathy, hypoxia and aspiration, pneumonia | Lungs | (i) Clindamycin + ceftriaxone | Died |

| (ii) Vancomycin + imipenem + amphotericin B | ||||||

| (iii) Polymyxin B | ||||||

| HUEC | 7 | 21 | Osteomyelitis | Bone | (i) Vancomycin + imipenem + amphotericin B | Died |

| (ii) Polymyxin B | ||||||

| HUEC | 11 | 48 | Abdominal sepsis and pancreatitis | Blood | (i) Piperacillin-tazobactam + gentamicin | Discharged |

| (ii) Vancomycin + imipenem | ||||||

| (iii) Polymyxin B | ||||||

| HC | 3 | 19 | Neurological disorder and pneumonia | Lungs | (i) Ceftriaxone + clindamycin | Died |

| (ii) Ceftazidime + clindamycin | ||||||

| (iii) Vancomycin | ||||||

| (iv) Cefepime | ||||||

| HC | 4 | 73 | Cerebral hemorrhage and pneumonia | Lungs | (i) Ceftriaxone | Died |

| (ii) Metronidazole | ||||||

| (iii) Levofloxacin | ||||||

| HC | 5 | 39 | Pneumonia | Lungs | (i) Ceftriaxone + clindamycin | Died |

| (ii) Ceftazidime | ||||||

| (iii) Vancomycin + cefepime | ||||||

| HC | 9 | 72 | Lung cancer; removal of right lung | Surgical wound | (i) Cephazolin | Discharged |

| (ii) Ceftazidime | ||||||

| (iii) Clindamycin | ||||||

| (iv) Cefepime | ||||||

| (v) Imipenem | ||||||

| HC | 10 | 80 | Pneumonia and pulmonary emphysema | Lungs | (i) Ceftriaxone | Discharged |

| (ii) Ceftazidime | ||||||

| (iii) Levofloxacin | ||||||

| (iv) Vancomycin | ||||||

| (v) Imipenem |

Infection with multiresistant A. baumannii was considered by the clinicians caring for the patients to have contributed to the deaths of five patients. Three patients survived, including the one who was considered to be only colonized. Polymyxin was consistently active in vitro and was used in one patient who survived infection and in two who died. The other patient who survived a significant infection received a complex series of antibiotics, none of which was individually active; complex antibiotic mixtures were received also by three infected patients who died at least partly as a result of their Acinetobacter infections (Table 1).

Bacteria were identified using the API 20NE system (Biomerieux, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and typed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) after digestion of genomic DNA with ApaI restriction enzyme (8). The running conditions for PFGE were a 5-s initial switching time and a 35-s final switching time for a total duration of 30 h at 12°C in a 1.2% molecular biology grade-certified agarose gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). MICs were determined with Etests (AB BIODISK, Solna, Sweden) on Iso-Sensitest agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) with incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Genes coding for class B and D carbapenemases were sought by PCR using a Taq DNA polymerase kit (Invitrogen) with primers specific for blaIMP (14), blaVIM (15), blaOXA-23-like (2), and blaOXA-24-like (5). PCR products were cleaned using a Hybaid DNA recovery kit II (Hybaid, Ashford, United Kingdom), and both strands were sequenced with a CEQ DTCS-Quick Start kit (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, United Kingdom). Contigs were assembled using GeneBuilder (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) and BioEdit (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html) programs.

MICs and β-lactamase gene detection results are shown in Table 2. The eight A. baumannii isolates were highly resistant to carbapenem, with imipenem and meropenem MICs of ≥32 μg/ml. Three control isolates obtained at the same time from other patients at HUEC were susceptible to the carbapenems, with MICs of 0.5 to 2 μg/ml for imipenem and meropenem. The carbapenem-resistant isolates were also resistant to ciprofloxacin, aminoglycosides, and other β-lactams, with the possible exception of ampicillin-sulbactam, for which the MICs were clustered around 16 to 32 μg/ml. The isolates were susceptible to polymyxin B (MICs, 0.5 μg/ml). By National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) criteria, the isolates were susceptible to minocycline (MICs, 1 to 4 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

MICs for A. baumannii isolates and carbapenemase gene detection

| A. baumannii isolate designation | blaOXA-23 detection by PCRa | Antibiotic MIC (μg/ml)b

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMK | AMP | CIP | CTX | CAZ | GEN | IPM | MEM | PIP | TZP | MIN | SAM | PMB | ||

| 1 | + | 32 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 4 | 16 | 0.25 |

| 3 | + | 64 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 1 | 32 | 0.5 |

| 4 | + | 32 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 4 | 16 | 0.5 |

| 5 | + | 4 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 8 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 2 | 16 | 0.5 |

| 7 | + | >256 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 2 | 64 | 0.5 |

| 9 | + | 128 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 2 | 16 | 0.5 |

| 10 | + | 192 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 1 | 16 | 0.5 |

| 11 | + | 64 | >256 | >32 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >32 | >32 | >256 | >256 | 4 | 32 | 0.5 |

| 2 | − | 64 | >256 | >32 | >256 | 192 | >256 | 0.5 | 2 | >256 | >256 | 2 | 8 | 0.5 |

| 6 | − | 64 | >256 | >32 | 256 | 16 | >256 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >256 | >256 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 |

| 8 | − | 128 | >256 | 8 | >256 | 32 | >256 | 0.5 | 1 | 256 | 128 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 |

blaOXA-24-like, blaIMP, and blaVIM genes were not detected in any isolate. +, detected; −, not detected.

Drug abbreviations: AMK, amikacin; AMP, ampicillin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CTX, cefotaxime; CAZ, ceftazidime; GEN, gentamicin; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; PIP, piperacillin; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; MIN, minocycline; SAM, ampicillin-sulbactam; PMB, polymyxin B.

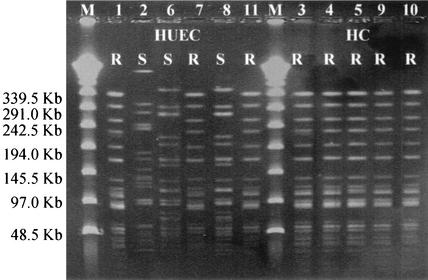

The eight carbapenem-resistant isolates gave a PCR product with primers specific for the blaOXA-23-like gene, but not with primers for other carbapenemase genes. Sequencing the 1,062-bp fragment confirmed the presence of the classical OXA-23 (ARI-1) enzyme, without any point mutations; blaOXA-23 was not detected in the carbapenem-susceptible control isolates. All eight carbapenem-resistant isolates from both hospitals gave identical PFGE patterns. The three carbapenem-susceptible control isolates from HUEC were distinct from the carbapenem-resistant strain, though two isolates appeared to be related to each other (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PFGE patterns of A. baumannii isolates from HUEC and HC. A. baumannii isolates that were resistant (R) or susceptible (S) to carbapenem are indicated. The isolates were assigned numbers, which are shown over the lanes in the gel and in Tables 1 and 2. The positions of molecular size markers (M) (in kilobases) are shown to the left of the gel.

Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii strains have been isolated in Europe, Asia, and both North and South America (11). Several of the earliest reports were from South America (1, 10). Carbapenemase production, penicillin-binding protein modification, and/or porin loss have been reported as mechanisms of resistance, with carbapenemase production increasingly viewed as the major mechanism (11). The carbapenemases mostly involved are metalloenzymes of the IMP family, but various OXA (class D) enzymes that have only weak carbapenemase activity in vitro are also involved. Those OXA carbapenemases that have been sequenced fall into two subgroups. Members of the OXA-24, -25, -26, and -40 subgroup have 98% sequence homology and are epidemiologically linked to Spain, where producers of OXA-24 and -40 have caused outbreaks (5, 11a). OXA-23 and -27 are closely related to each other (98% homology) but have only 60% amino acid homology to the OXA-24-like cluster. OXA-23 (formerly ARI-1) was originally reported from an A. baumannii detected in Scotland in 1985 (6, 12); OXA-27 was found in A. baumannii in Singapore between 1995 and 1997 (2). OXA-23 was also identified in clonal Proteus mirabilis isolates obtained in France from 1996 to 1999 (4).

This study revealed the presence of A. baumannii with the OXA-23 enzyme in Brazil, 14 years after the enzyme was first detected in Scotland. On the basis of identical PFGE patterns and antibiotic susceptibility test results, it seems that a single OXA-23-producing A. baumannii strain had spread between the two hospitals. The strain contributed to patient mortality even when polymyxin B, a drug with in vitro activity, was administered. Mixed responses to polymyxin B in multiresistant A. baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections were also reported by Levin et al. (9), who recorded an overall cure rate of 55% but a cure rate of only 25% for patients with pneumonia. Overcoming the combination of clonal spread and multiresistance is a challenge for the effective treatment of nosocomial A. baumannii infections. The relative merits of polymyxin, minocycline, and sulbactam therapy remain to be established in multiresistant Acinetobacter infections.

(This work was presented in part at the 42nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Diego, Calif., 27 to 30 September 2002.)

Acknowledgments

We thank AstraZeneca for supporting this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afzal-Shah, M., H. E. Villar, and D. M. Livermore. 1999. Biochemical characteristics of a carbapenemase from an Acinetobacter baumannii isolate collected in Buenos Aires, Argentina. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afzal-Shah, M., N. Woodford, and D. M. Livermore. 2001. Characterization of OXA-25, OXA-26, and OXA-27, molecular class D beta-lactamases associated with carbapenem resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:583-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergogne-Berezin, E., and K. J. Towner. 1996. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:148-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnet, R., H. Marchandin, C. Chanal, D. Sirot, R. Labia, C. De Champs, E. Jumas-Bilak, and J. Sirot. 2002. Chromosome-encoded class D beta-lactamase OXA-23 in Proteus mirabilis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2004-2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bou, G., A. Oliver, and J. Martinez-Beltran. 2000. OXA-24, a novel class D beta-lactamase with carbapenemase activity in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1556-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donald, H. M., W. Scaife, S. G. Amyes, and H. K. Young. 2000. Sequence analysis of ARI-1, a novel OXA beta-lactamase, responsible for imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii 6B92. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:196-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia, I., V. Fainstein, B. LeBlanc, and G. P. Bodey. 1983. In vitro activities of new beta-lactam antibiotics against Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 24:297-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouby, A., M. J. Carles-Nurit, N. Bouziges, G. Bourg, R. Mesnard, and P. J. Bouvet. 1992. Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for investigation of hospital outbreaks of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1588-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levin, A. S., A. A. Barone, J. Penco, M. V. Santos, I. S. Marinho, E. A. Arruda, E. I. Manrique, and S. F. Costa. 1999. Intravenous colistin as therapy for nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:1008-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin, A. S., C. M. Mendes, S. I. Sinto, H. S. Sader, C. R. Scarpitta, E. Rodrigues, N. Sauaia, and M. Boulos. 1996. An outbreak of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumanii in a university hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 17:366-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livermore, D. M. 2002. The impact of carbapenemases on antimicrobial development and therapy. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 3:218-224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Lopez-Otsoa, F., L. Gallego, K. J. Towner, L. Tysall, N. Woodford, and D. M. Livermore. 2002. Endemic carbapenem resistance associated with OXA-40 carbapenemase among Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a hospital in northern Spain. 40:4741-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Paton, R. H., R. S. Miles, J. Hood, and S. G. Amyes. 1993. ARI-1:β-lactamase-mediated imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poirel, L., and P. Nordmann. 2002. Acquired carbapenem-hydrolyzing betalactamases and their genetic support. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 3:117-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senda, K., Y. Arakawa, S. Ichiyama, K. Nakashima, H. Ito, S. Ohsuka, K. Shimokata, N. Kato, and M. Ohta. 1996. PCR detection of metallo-β-lactamase gene (blaIMP) in gram-negative rods resistant to broad-spectrum beta-lactams. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2909-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsakris, A., S. Pournaras, N. Woodford, M. F. Palepou, G. S. Babini, J. Douboyas, and D. M. Livermore. 2000. Outbreak of infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing VIM-1 carbapenemase in Greece. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1290-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]