Abstract

The gag-based heteroduplex mobility assay (gag-HMA) was evaluated for its ease and reliability in subtyping circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in Côte d'Ivoire. One hundred thirty-two plasma samples were analyzed blindly for HIV-1 subtypes by sequencing the pol gene and by gag-HMA. DNA sequencing was used as the “gold standard.” Of the 132 samples sequenced, 108 (82%) were CRF02_AG, 14 (11%) were pure subtype A, 5 (4%) were subtype G, 3 (2%) were subtype D, 1 was CRF01_AE, and 1 was subtype H. The gag-HMA correctly classified 126 (95.5%) of the samples. Of the 108 samples that were classified as CRF02_AG by DNA sequencing, 107 (99%) were correctly identified by gag-HMA, resulting in a positive predictive value of 96.4%. The gag-HMA seems to be a valuable tool for understanding the molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 CRF02_AG in Côte d'Ivoire and West Africa, which could be important for developing and evaluating AIDS vaccines, although DNA sequencing remains necessary for accurate molecular epidemiology.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is currently divided into three groups: M for major, O for outlier, and N for non-M, non-O (2, 9, 19). HIV-1 group M viruses are further divided into nine pure subtypes and 12 circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) (1, 2). CRF02_AG viruses are predominant in West and Central Africa, while CRF01_AE viruses are common in Central Africa and in Thailand and other Asian countries (1, 7, 9, 13). Although the clinical implication of the multitude of HIV subtypes is unknown, genetic diversity has been shown to impact diagnosis and may be important in vaccine development and evaluation (2, 3). Indeed, the first HIV-1 vaccine candidates in Africa are being matched with the predominant viruses in the country where the vaccine trials are planned (24). Thus, monitoring and characterization of HIV-1 diversity continue to be critical for developing or evaluating potential candidate vaccines and for understanding the spread of the HIV epidemic. Although full-length sequencing is the most accurate technique to characterize HIV viral genomes, it is technically challenging and expensive for use as a screening tool for large-scale surveillance, especially in field conditions in developing countries (3, 6, 7). To circumvent this problem, easier and faster techniques for subtyping have been developed, including peptide enzyme immunoassay and restriction fragment length polymorphism (2, 15), subtype-specific PCR (18), and env-based heteroduplex mobility assay (env-HMA) (8). Of these techniques, the env-HMA has been extensively used (6, 7, 9); however, because of the increasing global spread of CRFs (4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 16, 19, 20, 22), HIV subtyping based on only one gene of the virus genome may fail to detect CRFs. Thus, a gag-based HMA (gag-HMA) has recently been developed (9). The gag-HMA alone seems to detect some CRFs of epidemiological importance including CRF01_AE and CRF02_AG and pure subtypes (9), but it is unclear how this technique can identify CRF06_cpx. Limited data exist on the performance of the gag-HMA in field conditions and in areas like West Africa where CRF02_AG predominates (1, 15). Our study was aimed at evaluating the performance of the gag-HMA in classifying HIV-1 strains in Côte d'Ivoire, where CRF02_AG is predominant (1, 15).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

The plasma samples used in this evaluation were collected as part of an initiative started in 1998 by the Ivorian Ministry of Health in collaboration with the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, aimed at providing access to antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected persons in Côte d'Ivoire. Whole blood was collected and plasma was separated from cells as previously described (1). The HIV-1 strains obtained from the plasma samples that were used in this evaluation had been previously characterized by sequencing of the pol (protease and reverse transcriptase [RT]) regions of the viruses, and those data had been published elsewhere (1).

Laboratory testing.

HIV infection status was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based parallel testing algorithm (14). CD4+ lymphocytes were enumerated by standard flow cytometry with a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.), and HIV-1 RNA viral load in plasma was quantified with the Amplicor HIV-1 monitor (version 1.5; Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, N.J.).

RNA extraction and PCR amplification.

Viral RNA was extracted from plasma by the Qiagen method (Qiamp viral RNA kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the directions of the manufacturer. Extracted RNA was then used in a one-tube RT-PCR (Access RT-PCR system; Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands) with H1G777 (TCACCTAGAACTTTGAATGCATGGG) sense and H1P202 (CTAATACTGTATCATCTGCTGCTCCTGT) antisense primers as first-round primers. Nested PCR was then performed using H1Gag1584 (AAAGATGGATAATCCTGGG) sense and g17 (TCCACATTTCCAACAGCCCTTTTT) antisense primers to enable amplification of 460 bp encoding amino acid 132 of p24 to amino acid 40 of p7 from the gag gene. The amplification conditions of the RT-PCR were as follows: 45 min at 48°C (cDNA reaction) followed by 2 min at 94°C and 40 cycles of 30, 30, and 90 s at 94, 50, and 68°C, respectively, and 1 cycle of 7 min at 68°C. For nested PCR, cycling conditions were 1 cycle of 2 min at 94°C; 35 cycles of 30, 30, and 60 s at 94, 50, and 72°C, respectively; and 1 cycle of 7 min at 72°C.

gag-HMA.

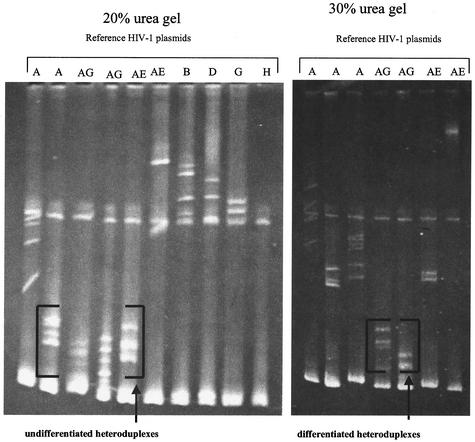

The gag-HMA was carried out blindly on all the samples. Heteroduplexes were obtained by mixing 4.5 μl of the 460-bp amplified fragment of the unknown subtype sample with the same amount of each of the amplified reference plasmids (gag-HMA kit; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, Md.) in 1× annealing buffer (1 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA); the mix was then denatured by being heated for 2 min at 94°C and rapidly cooled in wet ice. Heteroduplexes and homoduplexes were separated by electrophoresis on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (29:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio) containing 20% urea for 2 h 30 min. The gels were then stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under a UV transilluminator. The heteroduplexes formed by the sample and the reference DNA that migrate faster (close to the homoduplexes at the bottom of the gel) are most closely related to the specific reference DNA. On a 20% urea gel, not all the recombinants (CRF_02 and CRF_01) could be differentiated from pure subtype A because they are more closely related. However, at 30% urea, by increasing the denaturing condition of the gel and extending the electrophoresis time for up to 3 h, the recombinants could be distinguished from the pure subtype A (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Typical profile of a CRF02_AG (IBNG-like) sample, CI00297, with undifferentiated and differentiated heteroduplexes. Letters above the gel indicate reference plasmids used in determining subtypes in the HMA. Subtype assignment was based on heteroduplex migration pattern. CRF01_AE, CRF02_AG, and “pure” A were differentiated by altering the gel condition by increasing the urea concentration to 30% and extending the electrophoresis time for up to 3 h. The heteroduplexes formed by the sample and the references that migrate faster (close to the homoduplexes at the bottom of the gel) are most closely related to the specific reference plasmid. On a 20% urea gel, not all the recombinants (CRF_02 and CRF_01) could be differentiated from pure subtype A because they are closer. However, at 30% urea, by increasing the denaturing condition of the gel, the recombinants could be distinguished from the pure subtype A.

DNA sequencing.

The pol genes were sequenced as described previously (1). In brief, HIV-1 RNA was extracted from plasma by the Qiagen method (Qiamp viral RNA mini kit). The RNA was used in PCR amplification of 1.6 kbp of the pol gene by specific primers. We sequenced 200 ng of purified cDNA by the TrueGene HIV-1 genotyping assay (version 2.5; Visible Genetics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) (8).

For the gag gene, a 700-bp fragment corresponding to the p24 region from the gag gene was amplified with previously described primer pairs G00-G01 and G60-G25 (23). The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step for 3 min at 92°C, followed by 30 cycles of 92°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension for 7 min at 72°C, in a final volume of 50 μl. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mmol of KCl/liter, 10 mmol of Tris-HCl (pH 9)/liter, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1.4 mmol of MgCl2/liter, 10 pmol of each primer, 0.2 mmol of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate/liter, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase. One microliter from this amplified product was used for the second round with the same reaction mixture and PCR conditions for 40 cycles, in a final volume of 100 μl. The PCR amplification products were detected by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The amplification product was directly sequenced on both strands with fluorescent dye terminator and an ABI 3100 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). DNA sequences were edited with Sequencer software (Genecodes, Ann Arbor, Mich.) and aligned with reference sequences representing different subtypes with CLUSTAL and Bioedit software.

Analysis of data.

The HIV-1 subtypes obtained by gag-HMA were compared to those obtained by sequencing the pol (protease and RT) gene. The new nucleotide sequences and sequences of reference strains representing the different genetic subtypes in the gag, protease, and RT genes were aligned by using the CLUSTAL W program. Subtype results by pol gene sequencing were considered to be the “gold standard.”

RESULTS

Characteristics of study population.

For the samples from 132 HIV-1-infected patients analyzed, the median age was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR], 30 to 42 years), median CD4+ cell count was 166 cells/μl (IQR, 66 to 296), and median plasma viral load was 4.96 log10 copies/ml (IQR, 4.19 to 5.70). Of these 132 patients, 76 (57.6%) were males. The distribution of HIV-1 subtypes among the 132 patients according to the pol gene sequences was as follows: 108 (81%) were CRF02_AG strains, 14 (11%) were pure subtype A, 5 (4%) were subtype G, 3 (2%) were subtype D, 1 was CRF01_AE, and 1 was subtype H (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of HIV-1 subtypes by pol gene sequencing and gag-HMA

| HIV-1 subtype by gag-HMA | No. of samples with HIV-1 subtype by pol gene sequencing (n)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (14) | AE (1) | AG (108) | D (3) | G (5) | H (1) | |

| A | 10 | 1 | 1 | |||

| AE | 1 | |||||

| AG | 4 | 107 | ||||

| D | 2 | |||||

| G | 5 | |||||

| H | 1 | |||||

HIV-1 subtypes by gag-HMA.

All the 132 samples were amplified successfully by PCR testing and classified into subtypes by using reference plasmids from the gag-HMA kit. Of the 132 samples, 111 (84%) were classified as CRF02_AG, 12 (9%) were subtype A, 5 (4%) were subtype G, 2 were subtype D, 1 was subtype H, and 1 sample was CRF01_AE (Table 1).

Comparison of gag-HMA and pol gene sequencing results.

Next, we compared the results of HIV-1 subtypes obtained by gag-HMA to those obtained by pol gene sequencing (Table 1). Of the 108 samples that were classified as CRF02_AG by pol gene sequencing, 107 (99%) were correctly classified by gag-HMA and 1 sample could not be differentiated between pure subtype A and the CRF02_AG recombinant virus by gag-HMA. Of the 14 samples that were classified as subtype A by sequencing, 10 (71.4%) were correctly classified by gag-HMA, and 4 were classified as CRF02_AG. The gag-HMA correctly classified all five subtype G samples, the one CRF01_AE sample, and the one subtype H sample. Of the three pol gene sequence-based subtype D viruses, two were classified correctly by gag-HMA and the remaining one was classified as subtype A. The positive predictive value of the gag-HMA for correctly identifying CRF_AG was 96.4%, that is, 107 of the 111 strains classified by gag-HMA were truly CRF02_AG strains. Thus, overall, 126 (95.5%) of the samples analyzed gave concordant subtype results by pol gene sequences and gag-HMA analysis. However, if we group all the CRF02_AG and pure subtype A viruses in the same category of viruses, then only one sample was discordant between subtyping by HMA and that by DNA sequencing.

We investigated further the six samples that were discordant between gag-HMA and pol gene sequencing (Table 2). gag-HMA testing classified four of the six samples as CRF02_AG and two as subtype A. Of the six samples, five gave concordant results between gag-HMA testing and gag sequencing. Only one sample gave concordant results between gag and pol gene sequences (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

HIV-1 discordant subtypes by gag-HMA, pol, and gag testing

| Sample no. | Subtype by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| gag-HMA | pol sequencing | gag sequencing | |

| CI00731 | A | CRF02_AG | CRF02_AG |

| CI02012 | CRF02_AG | A | CRF02_AG |

| CI02340 | A | D | A |

| CI02598 | CRF02_AG | A | CRF02_AG |

| CI03047 | CRF02_AG | A | CRF02_AG |

| CI03764 | A | CRF02_AG | A |

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that, compared with pol gene sequencing, the gag-HMA has an overall accuracy of 95.5% for classifying HIV-1 strains in this study and a positive predictive value of 96.4% for classifying a mixture of pure and recombinant CRF02_AG viruses in Côte d'Ivoire. Our findings are consistent with the original report by Heyndrickx and colleagues, who found 96% (76 out of 79 viruses) concordance between genetic subtypes by DNA sequencing and by gag-HMA (9). In that study, the three strains that could not be classified were one subtype D and two subtype J strains (9). Pasquier and colleagues reported 84% concordance between env-HMA and RT gene-based subtyping among 49 HIV-1 samples and 79% concordance for the protease gene among 26 HIV-1 strains (17).

Our findings suggest that the gag-HMA may be a valuable tool for large-scale field epidemiologic studies of HIV-1 strains in Côte d'Ivoire and West Africa, where CRF02_AG is the predominant strain (1, 15). To our knowledge this is the first report of a field evaluation of the gag-HMA in West Africa. If our results are confirmed in other countries in West Africa, the gag-HMA could be a rapid, easy, and reliable tool for understanding the molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 subtypes in the subregion. Our data also show some limitations of the gag-HMA and the more accurate molecular characterization provided by the gold standard DNA sequencing of at least two genes. Knowledge of the molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 subtypes could be important in preparing vaccine evaluations in West Africa. Indeed, because HIV-1 candidate vaccines are being matched with the predominant subtype, simple and accurate techniques are needed for screening populations to determine the dynamics of HIV subtypes before, during, and after vaccine trials. For example, in Bangkok, Thailand, the epidemic that started among injection drug users in 1988 was predominantly due to subtype B strains, but during the 1990s, subtype E (CRF01_AE) emerged as the predominant subtype in this population (20).

The gag-HMA has some advantages over the env-HMA: first, although the env-HMA has been extensively used for assigning HIV-1 subtypes, its use in areas where CRFs are predominant is limited since it cannot differentiate between pure subtypes and the CRFs. Second, increasing numbers of global HIV-1 strains are not amplifiable within the env region with the C2-V5 primers that were developed for the present env-HMA kit (2, 21). Given the high predictive value of the gag-HMA, we proposed an algorithm for assigning subtypes in areas like West Africa where CRF02_AG viruses are predominant; this algorithm consists of analyzing all samples with the gag-HMA and limiting the use of DNA sequencing to only samples that are not assigned clearly as CRF02_AG by gag-HMA.

In conclusion, this field evaluation shows that the gag-HMA is reliable and easy to implement and provides results that are almost as accurate as those obtained by DNA sequencing for assigning CRF02_AG strains. Adapting the gag-HMA technique for analysis of blood samples obtained from a dried blood spot will render this technique even more practical for use in studying the molecular epidemiology of HIV subtypes in remote areas in Africa where blood samples may not be readily collected and centrifuged in the field.

Acknowledgments

We thank the African AIDS Vaccine Program for providing support and training of S.S. on the gag-based HMA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adje, C., R. Cheingsong, H. T. Roels, C. Maurice, G. Djomand, W. Verbiest, K. Hertogs, B. Larder, B. Monga, M. Peeters, S. Eholie, E. Bissagnene, M. Coulibaly, R. Respess, S. Z. Wiktor, T. Chorba, and J. N. Nkengasong for the UNAIDS HIV Drug Access Initiative, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. 2001. High prevalence of genotypic and phenotypic HIV-1 drug-resistant strains among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 26:501-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agwale, S. M., K. E. Robbins, L. Odama, A. Saekhou, C. Zeh, A. Edubio, O. M. Njoku, N. Sani-Gwarzo, M. F. Gboun, F. Gao, M. Reitz, D. Hone, T. M. Folks, D. Pieniazek, C. Wambebe, and M. L. Kalish. 2001. Development of an env gp41-based heteroduplex mobility assay for rapid human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2110-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AIDS. 2001. Approaches to the development of broadly protective HIV vaccines: challenges posed by the genetic, biological and antigenic variability of HIV-1. Report from a meeting of the WHO-UNAIDS Vaccine Advisory Committee, Geneva, 21-23 February 2000. AIDS 15:W1-W25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldrich-Rubio, E., S. Anagonou, K. Stirrups, E. Lafia, D. Candotti, H. Lee, and J. P. Allain. 2001. A complex human immunodeficiency virus type 1 A/G/J recombinant virus isolated from a seronegative patient with AIDS from Benin, West Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1095-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow, K. L., I. D. Tatt, P. A. Cane, D. Pillay, and J. P. Clewley. 2001. Recombinant strains of HIV type 1 in the United Kingdom. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:467-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cham, F., L. Heyndrickx, W. Janssens, K. Vereecken, K. De Houwer, S. Coppens, G. Van der Auwera, H. Whittle, and G. Van der Groen. 2000. Development of a one-tube multiplex reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay for the simultaneous amplification of HIV type 1 group M gag and env heteroduplex mobility assay fragments. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1503-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cham, F., L. Heyndrickx, W. Janssens, G. Van der Auwera, K. Vereecken, K. De Houwer, S. Coppens, H. Whittle, and G. Van der Groen. 2000. Study of HIV type 1 gag/env variability in The Gambia, using a multiplex DNA polymerase chain reaction. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1915-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delwart, E. L., B. Herring, A. G. Rodrigo, and J. I. Mullins. 1995. Genetic subtyping of human immunodeficiency virus using a heteroduplex mobility assay. PCR Methods Appl. 4:S202-S216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heyndrickx, L., W. Janssens, L. Zekeng, R. Musonda, S. Anagonou, G. van der Auwera, S. Coppens, K. Vereecken, K. De Witte, R. van Rampelbergh, M. Kahindo, L. Morison, F. E. McCutchan, J. K. Carr, J. Albert, M. Essex, J. Goudsmit, B. Asjo, M. Salminen, A. Buve, Study Group on Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities, and G. van der Groen. 2000. Simplified strategy for detection of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group M isolates by gag/env heteroduplex mobility assay. J. Virol. 74:363-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koulinska, I. N., T. Ndung'u, D. Mwakagile, G. Msamanga, C. Kagoma, W. Fawzi, M. Essex, and B. Renjifo. 2001. A new human immunodeficiency virus type 1 circulating recombinant form from Tanzania. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:423-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kusagawa, S., Y. Takebe, R. Yang, K. Motomura, W. Ampofo, J. Brandful, Y. Koyanagi, N. Yamamoto, T. Sata, K. Ishikawa, Y. Nagai, and M. Tatsumi. 2001. Isolation and characterization of a full-length molecular DNA clone of Ghanaian HIV type 1 intersubtype A/G recombinant CRF02_AG, which is replication competent in a restricted host range. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:649-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montavon, C., F. Bibollet-Ruche, D. Robertson, B. Koumare, C. Mulanga, E. Esu-Williams, C. Toure, S. Mboup, E. Saman, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 1999. The identification of a complex A/G/I/J recombinant HIV type 1 virus in various West African countries. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1707-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montavon, C., C. Toure-Kane, F. Liegeois, E. Mpoudi, A. Bourgeois, L. Vergne, J. L. Perret, A. Boumah, E. Saman, S. Mboup, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2000. Most env and gag subtype A HIV-1 viruses circulating in West and West Central Africa are similar to the prototype AG recombinant virus IBNG. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 23:363-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nkengasong, J. N., C. Maurice, S. Koblavi, M. Kalou, D. Yavo, M. Maran, C. Bile, K. Nguessan, J. Kouadio, S. Bony, S. Z. Wiktor, and A. E. Greenberg. 1999. Evaluation of HIV serial and parallel serologic testing algorithms in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. AIDS 13:109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nkengasong, J. N., C.-C. Luo, L. Abouya, D. Pieniazek, C. Maurice, M. Sassan-Morokro, D. Ellenberger, D. J. Hu, C.-P. Pau, T. Dobbs, R. Respess, D. Coulibaly, I.-M. Coulibaly, S. Z. Wiktor, A. E. Greenberg, and M. Rayfield. 2000. Distribution of HIV-1 subtypes among HIV-1 seropositive patients in the interior of Cote d'Ivoire. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 23:430-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oelrich, R. B., C. Workman, T. Laukkanen, F. E. McCutchan, and N. J. Deacon. 1998. A novel subtype A/G/J recombinant full-length HIV type 1 genome from Burkina Faso. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:1495-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasquier, C., N. Millot, R. Njouom, K. Sandres, M. Cazabat, J. Puel, and J. Izopet. 2001. HIV-1 subtyping using phylogenetic analysis of pol gene sequences. J. Virol. Methods 94:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peeters, M., F. Liegeois, F. Bibollet-Ruche, D. Patrel, J.-L. Perret, N. Vidal, E. Esu-Williams, S. Mboup, E. Mpoudi, N. Nzila, and E. Delaporte. 1998. Subtype-specific polymerase chain reaction for the identification of HIV-1 genetic subtypes circulating in Africa. AIDS 12:671-673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson, D. L., J. P. Anderson, J. A. Bradac, J. K. Carr, B. Foley, R. K. Funkhouser, F. Gao, B. H. Hahn, M. L. Kalish, C. Kuiken, G. H. Learn, T. Leitner, F. McCutchan, S. Osmanov, M. Peeters, D. Pieniazek, M. Salminen, P. M. Sharp, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber. 1999. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. A reference guide to HIV-1 classification. In B. Korber, C. Brander, B. F. Haynes, J. P. Moore, R. Koup, B. D. Walker, and D. I. Watkins (ed.), HIV molecular immunology database 1999. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex. [Online.] http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/content/hiv-db/reviews/nomenclature/Nomen.html.

- 20.Subbarao, S., S. Vanichseni, D. J. Hu, D. Kitayaporn, K. Choopanya, S. Raktham, N. L. Young, C. Wasi, R. Sutthent, C.-C. Luo, A. Ramos, and T. D. Mastro. 2000. Genetic characterization of HIV-1 subtype E and B strains from a prospective cohort of injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:699-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatt, I. D., K. L. Barlow, and J. P. Clewley. 2000. A gag gene heteroduplex mobility assay for subtyping HIV-1. J. Virol. Methods 87:41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson, M. M., E. Delgado, N. Majon, A. Ocampo, M. L. Villahermosa, A. Marino, I. Herrero, M. T. Cuevas, E. Vasquez-de Parga, L. Perez-Alvarez, L. Medrano, J. A. Taboada, R. Najera, and the Spanish Group for Antiretroviral Studies in Galicia. 2001. HIV-1 genetic diversity in Galicia, Spain: BG intersubtype recombinant viruses circulating among injecting drug users. AIDS 15:509-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vidal, N., M. Peeters, C. Mulanga-Kabeya, N. Nzilambi, D. Robertson, W. Ilunga, H. Sema, K. Tshimanga, B. Bongo, and E. Delaporte. 2000. Unprecedented degree of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M genetic diversity in the Democratic Republic of Congo suggests that the HIV-1 pandemic originated in central Africa. J. Virol. 74:10498-10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidle, P. J., T. D. Mastro, A. D. Grant, J. N. Nkengasong, and D. Macharia. 2002. HIV/AIDS treatment and HIV vaccines for Africa. Lancet 359:2261-2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]