Abstract

RNA of the newly identified human metapneumovirus (HMPV) was detected in nasopharyngeal aspirates of 11 of 63 (17.5%) young children with respiratory tract disease. Markers of infection caused by another member of the Pneumovirinae subfamily of the family Paramyxoviridae, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), were identified in 15 of these patients (23.8%). Three patients were simultaneously infected with HMPV and RSV. Studies of the clinical characteristics of HMPV-infected children did not reveal any difference between HMPV-infected patients and a control population of RSV-infected patients with regard to disease severity, but the duration of symptoms was significantly shorter for HMPV-infected patients. Phylogenetic analysis of the amplified viral genome fragments confirmed the existence and simultaneous circulation within one epidemic season of HMPV isolates belonging to two genetic lineages.

Recently, a new infectious agent, human metapneumovirus (HMPV), was isolated from nasopharyngeal aspirates of young children with respiratory tract illness from The Netherlands (7). HMPV, together with avian pneumovirus serotypes A, B, C, and D, form the Metapneumovirus genus of the Pneumovirinae subfamily of the family Paramyxoviridae (7, 8). Information on the biology of HMPV, as well as on the prevalence and clinical significance of HMPV infection, is scarce. Preliminary data, however, demonstrated that HMPV can cause severe respiratory disease in children younger than age 5 years (2, 3, 4, 6, 7). These observations suggest that HMPV can play an important role in the infectious pathology of humans and indicate the necessity of more detailed study of this agent and infections caused by this agent. Here, we report on the prevalence and clinical characteristics of HMPV infection in children with respiratory disease from Germany and on the genetic heterogeneity of the HMPV isolates identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

Nasopharyngeal aspirates were collected from 63 hospitalized patients younger than age 2 years. These patients represented all children in this age group admitted to the Essen University Hospital with upper or lower respiratory tract infection between January and May 2002. Most of these patients presented with wheezing and/or signs of respiratory distress (Table 1). The clinical data for the HMPV-infected patients were compared to those for a control group of children from the same population infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

TABLE 1.

Clinical data for the study population

| Virus and patient no. | Respiratory tract disease diagnosis | Age (mo) | Treat- menta | Duration of symptoms (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMPV | ||||

| 1 | Bronchiolitis | 2 | 1* | 3 |

| 2 | Bronchiolitis | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Bronchiolitis | 12.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 4 | Bronchiolitis | 1.5 | 2 | 5 |

| 5 | Bronchiolitis, pneumonia | 4 | 2 | 10 |

| 6 | Bronchiolitis | 9.5 | 2 | 6 |

| 7 | Bronchitis | 12 | 0 | 4 |

| 8 | Bronchiolitis | 24 | 1 | 2 |

| Mean ± SD | 9.2 ± 7.3 | 3.9 ± 3.1 | ||

| RSV | ||||

| 1 | Bronchiolitis | 3.5 | 2 | 12 |

| 2 | Bronchiolitis, pneumonia | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 3 | Bronchiolitis | 5.5 | 2 | 9 |

| 4 | Bronchiolitis, pneumonia | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 5 | Bronchiolitis | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| 6 | Bronchiolitis, pneumonia | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| 7 | Bronchiolitis, pneumonia | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| 8 | Rhinitis | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 9 | Bronchiolitis | 23 | 3 | 25 |

| 10 | Bronchiolitis | 12.5 | 1 | 4 |

| 11 | Bronchiolitis, neumonia | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| 12 | Bronchiolitis | 24 | 1 | 9 |

| Mean ± SD | 7.3 ± 8.4 | 8.4 ± 6.0b | ||

| HMPV + RSV | ||||

| 1 | Bronchiolitis, pneumonia | 13.5 | 2 | 11 |

| 2 | Bronchiolitis, pneumonia | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 3 | Bronchiolitis | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Mean ± SD | 5.2 ± 7.2 | 8.3 ± 2.5 |

0, none; 1, bronchodilators; 2, steroids; 3, intubation.

P < 0.04 compared to the HMPV-infected group (Wilcoxon test).

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR for HMPV RNA.

RNA was extracted from nasopharyngeal aspirates with the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) and reverse transcribed and amplified with two primer sets. Information on the first set, which included two primers whose sequences were derived from the L gene and which generated a DNA fragment of 171 bp, was kindly provided by van den Hoogen et al. (7). The second set was designed in the present study. It included four primers whose sequences were derived from the nucleocapsid (N) gene. Primer 750as (5′-TGCTTTGCTGCCTGTAGATGATGAG) was used to generate the cDNA. Reverse-transcribed cDNA was subjected to the first round of a 30-cycle PCR with primers 111s (5′-AGAGTCTCAGTACACAATMAAAAGAG) and 750as. The second round of the 30-cycle PCR was run with primers 114s (5′-AGAGTCTCAGTACACAATMAAAAGRGATG) and 442as (5′- GCCATTGTTTTYCTTGCYTC). Each cycle included denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Detection of RSV.

Infection caused by RSV was diagnosed by direct immunofluorescence (BioMerieux), according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

The amplified DNA was gel purified with the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (QIAGEN), cloned in the pTOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen), and subjected to sequencing in both directions (Dye Terminator DNA sequencing kit; Perkin-Elmer). Newly obtained sequences were compared with HMPV sequences taken from the GenBank database by phylogenetic analysis with the programs DNADIST and NEIGHBOR from the package PHYLIP (version 3.5c; J. Felsenstein, Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle, 1993). The significance of the grouping was evaluated by bootstrap analysis (100 replicates) with the program SEQBOOT.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The HMPV sequences obtained in the present study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF543686 to AF543690.

RESULTS

Nasopharyngeal aspirate samples from 63 patients with respiratory illness were tested for the presence of HMPV RNA in parallel with two primer sets. Five positive samples from three patients were detected with the set used in the original study of HMPV (7). All five of these samples plus nine samples from an additional eight patients were positive with the second set of primers. Cloning and sequencing of the amplified fragments confirmed the specificity of the PCR for all positive samples. Thus, the nested RT-PCR based on the primer set designed in the course of the present study appears to be more sensitive. Overall, HMPV RNA was found in 11 of 65 patients (17.5%). Five patients were positive for HMPV RNA after the first round of PCR, and an additional six patients were positive for HMPV RNA after the second round of PCR. The frequency of detection of the RSV antigen by direct immunofluorescence in the nasopharyngeal aspirates from the same patients was slightly higher (15 of 63 samples; 23.8%). Three patients were simultaneously found to be positive for markers of HMPV infection and RSV infection. One patient became positive for RSV antigen during hospitalization and after the disappearance of HMPV RNA.

HMPV-positive samples were detected in materials collected between January (beginning of the study) and April 2002. Although RSV-positive samples were identified in May, no HMPV-positive samples were identified in May.

No obvious difference in the frequencies of HMPV RNA detection in different age groups of patients was noted. Serial aspirate samples were available from three HMPV-infected patients. In one of these patients, HMPV RNA was detected for at least 20 days.

Comparative analysis of the clinical characteristics of HMPV-positive patients and children infected with RSV showed that both groups were similar with respect to age and sex. An underlying respiratory disorder was present in one patient in both groups (larynx stenosis for the patient in the HMPV group, bronchopulmonary dysplasia for the patient in the RSV group). Most patients had bronchiolitis alone or bronchiolitis in combination with pneumonia (Table 1). There were no significant differences with regard to the severity of symptoms between the two groups, although pneumonia tended to be more frequent in RSV-infected patients (5 of 12 patients among the RSV-infected children versus 1 of 8 patients among the HMPV-infected children [P = 0.17 by Fisher's exact test]). Only one patient in the RSV-infected group required intubation and mechanical ventilation. The duration of symptoms was variable between patients, but was significantly shorter in the HMPV-infected group (P < 0.04 by the Wilcoxon test).

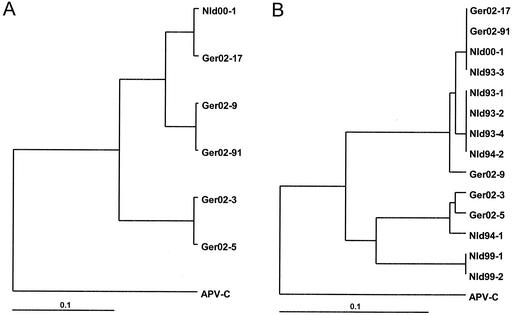

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the N-gene fragments of the HMPV isolates identified showed heterogeneity distributed evenly throughout the whole fragment sequenced. Phylogenetic analysis of the HMPV sequences corresponding to the 613-bp fragments obtained after the first round of PCR from five patients revealed two major clusters (Fig. 1A). The levels of similarity between the sequences within each cluster varied from 93 to 99%, and the level of similarity between the sequences forming these two clusters was about 86%. Smaller fragments (71 bp) of these five sequences were additionally compared with the corresponding sequences of HMPV variants isolated in The Netherlands (1). A tree with a similar topography, namely, a segregation of the HMPV sequences into two major groups, was observed upon analysis with those sequences (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of HMPV isolates. Comparison of the sequences of 613-bp (A) or 71-bp (B) fragments of the N gene. Nld, sequences of the HMPV variants isolated in The Netherlands (7); APV-C, sequence of the N-gene fragment of avian pneumovirus serotype C (GenBank accession no. AF176590).

DISCUSSION

This paper reports on the frequency of HMPV infection in a nonpreselected group of young children attending a hospital with symptoms of a respiratory tract disease. Most of the previous publications referred to the detection of HMPV in special groups of patients who were found to be negative for the markers of infections caused by other respiratory viruses (2-7). Taking into account our observations on the occurrence of double infections caused by both HMPV and RSV, one might presume that such a preselection could lead to an underestimation of the true incidence of HMPV infection. In our study, HMPV RNA was identified in 11 of 63 patients (17.5%). This frequency is comparable to that of RSV infection in the same group (23.8%). One should note, however, that such a comparison should be considered carefully because the cases of HMPV and RSV infections in this study were identified by absolutely different diagnostic techniques (RT-PCR and immunofluorescence assay, respectively). It is also possible that the RT-PCR protocols used in this and other studies are not optimal for the detection of all HMPV variants.

Our results demonstrating that the spectrum of clinical symptoms in HMPV-infected children is similar to that in patients with respiratory disease caused by RSV confirm the previous observations (7). Taken together with the data on the high incidence of HMPV infection, these results suggest that for young children, HMPV could be a pathogen as important as RSV. Preliminary data from the most recent reports (1, 5) indicate that this may also hold true for adults, especially those with impaired immunity. Even though disease severity was not significantly different between HMPV- and RSV-infected children, the duration of symptoms requiring treatment appeared to be shorter in HMPV-infected patients. A larger sample size will be needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

The data from the present study further extend the observations on the evident heterogeneity of the HMPV genome (5, 7). At the moment, there is some difficulty with the detailed analysis of the HMPV sequences available, as the genome fragments sequenced (most of which were rather short) were generated with primers derived from different parts of the viral genome. Nevertheless, comparison of the sequences of the relatively short fragments (71 bp) of the N gene of HMPV isolates from the present study with the sequences available in the GenBank revealed the existence of two major clusters (Fig. 1B). Similar bifurcation into two major branches occurred upon comparison of a smaller number of sequences of longer fragments (613 bp) of the N gene (Fig. 1A). These results, together with the data reported earlier for both the N gene and several other viral genome regions (5, 7), provide evidence for the existence and simultaneous circulation of HMPV isolates belonging to two evolutionary lineages. The heterogeneity of the HMPV genome evidently may pose a diagnostic problem. One cannot exclude the existence of other variants of HMPV which are not detected by the sets of primers in use. Further studies of the heterogeneity of the HMPV genome are therefore needed to clarify this crucial issue and to optimize diagnostic procedures to detect this important pathogen of humans.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yvonne Pietsch for skillful technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boivin, G., Y. Abed, G. Pelletier, L. Ruel, D. Moisan, S. Cote, T. C. Peret, D. D. Erdman, and L. J. Anderson. 2002. Virological features and clinical manifestations associated with human pneumovirus: a new paramyxovirus responsible for acute respiratory-tract infections in all age groups. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1330-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freymouth, F., A. Vabret, L. Legrand, N. Eterradossi, F. Lafay-Delaire, J. Brouard, and B. Guillois. 2003. Presence of the new human metapneumovirus in French children with bronchiolitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22:92-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackay, I. M., K. C. Jacob, D. Woolhouse, K. Waller, M. W. Syrmis, D. M. Whiley, D. J. Siebert, M. Nissen, and T. P. Sloots. 2003. Molecular assays for detection of human metapneumovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:100-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nissen, M. D., D. J. Siebert, I. M. Mackay, T. P. Sloots, and S. J. Withers. 2002. Evidence of human metapneumovirus in Australian children. Med. Aust. J. 176:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peret, T. C. T., G. Boivin, Y. Li, M. Couillard, C. Humphrey, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, D. D. Erdman, and L. J. Anderson. 2002. Characterization of human metapneumoviruses isolated from patients in North America. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1660-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stockton, J., I. Stephenson, D. Fleming, and M. Zambon. 2002. Human metapneumovirus as a cause of community-acquired respiratory illness. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:897-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Hoogen, B. G., J. C. de Jong, J. Groen, T. Kuiken, R. de Groot, R. A. M. Fouchier; and A. D. M. E. Osterhaus. 2001. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat. Med. 7:719-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Hoogen, B. G., T. M. Bestebroen, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, and R. A. M. Fouchier. 2002. Analysis of the genomic sequence of a human metapneumovirus. Virology 295:119-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]