Abstract

The newly described human metapneumovirus (hMPV) is reported here to be more commonly associated with lower respiratory tract disease. The present study examined nasal swab specimens from 90 infants with acute respiratory tract infections in Pisa, Italy, over a period of three respiratory virus seasons. The incidence of infection varied in each of the 3 years, with the rates of positivity for hMPV being 7% in 2001 but 37 and 43% in 2000 and 2002, respectively. hMPV was noted to occur seasonally in a pattern typical of the frequency of occurrence of respiratory syncytial virus. More than one-half (14 of 23) of the infants infected with hMPV had bronchopneumonia. One-third (9 of 23) of the hMPV-infected patients were also infected with another respiratory virus, a relationship that has not previously been reported. Mixed infections did not account for a higher percentage of cases of bronchopneumonia than hMPV infection alone did. Furthermore, 7 of 17 infants whose plasma was also tested for hMPV RNA were demonstrated to have virus in both nasal swab and blood specimens. The study indicates that hMPV is seen as commonly as other respiratory viruses, may be associated with severe respiratory disease in infants, can establish mixed infections with other respiratory viruses, and has a seasonal occurrence.

A newly identified virus capable of causing acute human respiratory disease has been reported (12) and demonstrated to be present mostly in children in Europe, North America, and Australia (2, 7, 9), suggesting a worldwide distribution. The name human metapneumovirus (hMPV) has been suggested for this paramyxovirus but awaits formal classification by the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses. This would place the virus in the genus metapneumovirus, which previously included only avian metapneumoviruses (3). Metapneumoviruses are pleomorphic, enveloped virions with an average diameter of approximately 200 nm (range, 150 to 1,000 nm), contain single-stranded RNA of negative polarity that forms a helical nucleocapsid, and have surface glycoproteins and projections (3, 9, 12, 13). Filamentous rod-like particles have also been seen by electron microscopy (12). The virus is not able to agglutinate red blood cells (12). Sequence analysis of the RNA of isolates of the virus has revealed that it is most closely related to avian metapneumovirus subtype C and is more closely related to all avian metapneumoviruses than to other paramyxoviruses, including the human respiratory pathogens parainfluenza viruses and human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) (13). Both serologic and molecular analyses have shown that the virus is unique compared to all other known human respiratory pathogens.

In retrospective studies the virus has been detected in numerous respiratory specimens from individuals with respiratory infections for which an etiologic agent was not initially detected. The reason for the difficulty in isolating this virus is that it does not grow readily in tissue culture cells routinely used in the viral diagnostic laboratory and grows only slowly in tertiary monkey kidney cells (12). In the few studies reported to date, it appears that less than 10% of respiratory infections for which no causative agent was previously identified may have been due to hMPV (7). van den Hoogen and colleagues (12) report that 100% of individuals 5 to 10 years of age or older who were tested serologically showed antibodies and that by age 2 years 55% were positive. Despite the evidence of antibodies in every adult tested, the virus was isolated from some adults with acute respiratory disease, suggesting that repeated infections may occur, as is seen with hRSV (1, 9). Molecular tools have been developed so that the virus can be detected by PCR as well as serologically (9, 12, 13). A serosurvey of specimens collected in 1958 showed that the virus has circulated in The Netherlands for at least 44 years, but no studies have examined older sera (12).

Sequence analysis has demonstrated that there are two major groups or lineages of hMPV and that sequence diversity exists within the groups (13). Specimens from one child that were collected in consecutive years demonstrated that the child had been infected with hMPV isolates of the two different subgroups each year, indicating that an individual may be infected with a virus from one subgroup and not be protected by a previous infection with virus of the other subgroup (8).

Clinical disease associated with hMPV appears to be similar to that associated with hRSV, ranging from mild upper respiratory tract infection to bronchiolitis and bronchopneumonia (1, 4, 7, 9, 11, 12). Studies with juvenile birds and monkeys suggest that the virus replicates and can cause respiratory symptoms of infection in the primates but not in the avian species (12). In that study no virus was detected in the monkeys at 24 h postinfection, but virus titers peaked between 2 and 8 days postinfection (12). Additionally, in that study ferrets and guinea pigs were inoculated with virus to generate antibodies, but the animals exhibited no evidence of clinical infection.

In the present study, the diagnostic virology laboratory at the University of Pisa examined 90 nasal swab specimens from infants (age, less than 2 years) routinely submitted for the examination of respiratory tract infections. This study indicated that hMPV was present in our patient population and that the incidence varied in each of the 3 years tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients, sample collection, and routine tests.

Simultaneous nasal and plasma specimens were harvested on the day of admission, following the receipt of informed parental consent, from 90 children with acute respiratory diseases (42 children with bronchopneumonia, 48 children with milder forms of acute respiratory disease) admitted to the Department of Pediatrics, University Hospital of Pisa. All children were negative for hepatitis B virus surface antigen and hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies, and none had received antiviral drugs. The nasal secretions of these children were quantified by weighing the swabs before and after collection and were then diluted 1:10 (wt/vol) with phosphate-buffered saline and clarified by centrifugation at 900 × g at 4°C for 10 min to separate the cells and cell debris. Finally, the cell-free nasal fluid was stored in aliquots at −20°C until RNA extraction. All nasal swab samples were tested for common respiratory viruses by direct immunofluorescence (adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses types 1 to 3, hRSV), enzyme immunoassay (hRSV), and rapid culture in shell vials (all viruses mentioned above). Plasma was obtained by spinning down blood collected under nuclease-free conditions in tubes containing sodium citrate.

hMPV PCR.

A 170-bp segment of the L gene spanning nucleotides 11321 to 11490 of hMPV prototype strain 00-1 was amplified by using a single-step reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Briefly, viral RNA was extracted with the QIAmp Viral RNA kit (QIAgen, Chatsworth, Calif.) and amplified with the OneStep RT-PCR kit (QIAgen) with antisense primer L7 (5′-CACCCCAGTCTTTCTTGAAA-3′; positions 11471 to 11490) and sense primer L6 (5′-CATGCCCACTATAAAAGGTCAG-3′; positions 11321 to 11342) under the following conditions: reverse transcription at 50°C for 30 min; an initial PCR activation step at 95°C for 15 min; and 40 subsequent PCR cycles with melting at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 60 s. The reactions were carried out in a 50-μl format by using a PCR Master Mix containing RT-PCR enzyme mix (Omniscript and Sensiscript reverse transcriptases and HotStartTaq DNA polymerase), each deoxynuceloside triphosphate at a concentration of 400 μM, primers (0.9 μM each), and optimized buffer components. Finally, the amplified product was analyzed by electrophoresis on an agarose gel after ethidium bromide staining, and the sizes of the amplicons were compared with standard molecular size markers. To validate the amplification process and to exclude the presence of carryover contamination, positive and negative controls were run in each PCR. All samples were tested at least in duplicate, and those found to be positive were tested again starting from an independent RNA extraction. The sensitivity of the assay was measured by testing serial dilutions of a known concentration of RNA transcribed from a recombinant plasmid into which the target fragment of the L gene of hMPV was inserted and was found to be less than 10 RNA copies. Specificity was demonstrated by sequencing a large number of the amplification products.

Sequencing.

The region sequenced was a 128-bp segment (nucleotides 11343 to 11470) obtained by subtracting the primer nucleotides from the 170-bp amplicon. Sequencing was carried out in both orientations by using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and an automatic DNA sequencer (ABI model 310; Applied Biosystems). The nucleotide sequences were aligned with previously published sequences. Multiple-sequence alignments were performed by the CLUSTALW method with a 102-bp segment known to be valuable for hMPV genotyping (9, 12) and for which a large number of sequences exist in GenBank.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank and have been given accession numbers AY168973 to AY168987.

RESULTS

Evidence of hMPV infections.

The patients recruited for this study comprised 90 children (60 males, 30 females; age range, 1 to 24 months; mean age, 7.8 ± 5.5 months) hospitalized from January 2000 to May 2002. Nasal swabs from these children were tested for hMPV by PCR with a primer set specific for the L protein (polymerase) which detects both genotypes of the virus (5, 9, 12), and 23 nasal swabs yielded positive results (Table 1). The rate of positivity held rather steady at about 25% when the subjects were divided into three age groups, although the youngest patients had the highest rate of positivity.

TABLE 1.

hMPV RNA detection in nasal swabs from 90 infants with acute respiratory diseases

| Parameter | No. of infants examined | No. (%) of infants hMPV RNA positive |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mo) | ||

| ≤3 | 11 | 4 (36) |

| 4-12 | 44 | 12 (27) |

| 13-24 | 35 | 7 (20) |

| Common respiratory viruses | ||

| Negative | 62 | 14 (23) |

| Positive | ||

| hRSV alone | 20 | 4 (20) |

| Othersa | 8 | 5b,c (62) |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||

| Bronchopneumonia | 42 | 14 (33) |

| Bronchiolitis | 33 | 7 (21) |

| Bronchitis | 8 | 1 (12) |

| Laryngitis | 7 | 1 (14) |

| Total | 90 | 23 (25) |

Including cytomegalovirus (n = 3), adenovirus (n = 3), influenza A virus (n = 1), and parainfluenza virus type 3 (n = 1).

Another virus, one adenovirus and one parainfluenza virus type 3, was also present in two nasal fluid specimens positive for hRSV.

Significantly different from the results for specimens with hRSV alone and negative specimens at P = 0.03 and P = 0.017, respectively (chi-square test).

Interestingly, of 28 specimens in which hRSV or other viruses were detected in infants, 9 were positive for hMPV and another virus and 2 specimens yielded a mixed infection with three viruses. Twenty-one of 75 (28%) samples from patients who exhibited lower respiratory tract infections (bronchiolitis or pneumonia) were hMPV positive, and 2 of 15 (13%) samples from patients with only upper respiratory tract infections were hMPV positive.

hMPV and association with disease severity.

Nasal swabs from 42 infants were found to be positive for one or more viruses (Table 2). Twenty-three of these infants were demonstrated to have hMPV in their nares, and 14 (61%) of these developed bronchopneumonia, while those infected with other viruses had a bronchopneumonia rate of only 16% (3 of 19 infants). The rate of bronchopneumonia was not altered by the presence of a second virus in infants with hMPV. Thus, the majority of patients demonstrating hMPV in nasal swabs developed pneumonia, while lung involvement was noted in a smaller proportion of patients infected with other viruses. When the plasma of 17 individuals whose nasal swabs were positive for hMPV was subsequently tested for viral RNA, the plasma of 7 was found to be positive (Table 2). Of these seven individuals, 5 had bronchopneumonia and 2 had milder acute respiratory disease.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of hMPV and/or other respiratory viruses in the 42 infants found to be virus positive and grouped by clinical diagnosis

| Virus | No. of infants tested | No. (%) of infants with:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchopneumonia | Milder ARDa | ||

| hMPV alone | 14 | 9b (64) | 5c (36) |

| hMPV and other RVd | 9 | 5e (56) | 4f (44) |

| Other RV alone | 19 | 3 (16)g | 16 (84) |

ARD, acute respiratory diseases, including bronchiolitis, bronchitis, and laryngitis.

The plasma of four of eight patients whose plasma was tested was positive.

The plasma of one of four patients whose plasma was tested was hMPV positive.

RV, respiratory viruses.

The plasma of one of three patients whose plasma was tested was hMPV positive.

The plasma of one of two patients whose plasma was tested was hMPV positive.

Significantly different from the results for patients positive for bronchopneumonia caused by hMPV alone and positive for bronchopneumonia caused by hMPV and respiratory viruses at P = 0.004 and P = 0.03, respectively (chi-square test).

hMPV and seasonal distribution.

The specimens studied were collected mainly during the respiratory disease seasons of three calendar years, 2000, 2001, and 2002 (Table 3). There was a distinct difference in the number of hMPV-positive specimens in 2001 compared with the numbers in the other two years, with the numbers of hMPV-positive specimens in 2000 and 2002 being essentially identical. The data for hMPV are consistent with the findings for all viruses isolated from 171 nasal swab specimens in the same patient population; rates of isolation in 2001 were lower for all respiratory viruses. Testing for hMPV was not performed with the specimens from patients older than age 2 years. However, the decrease in the rate of hMPV detection was statistically significant compared to the rate of detection in the other years, similar to the observation for other respiratory viruses. While a decrease in the number of hMPV-positive specimens was also noted for hRSV in 2001 compared to the numbers in the other years, it was not statistically significant.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of hMPV and other respiratory viruses in nasal swabs specimens grouped by year of sampling

| Yr | hMPV

|

Other RVa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of specimens examinedb | No. (%) positive | Total no. of specimens examined | No. (%) positive | No. (%) RSV positive | |

| 2000 | 19 | 7 (37) | 80 | 44 (55) | 29 (36) |

| 2001 | 41 | 3 (7)c | 59 | 22 (37)d | 16 (27) |

| 2002 | 30 | 13 (43) | 32 | 18 (56) | 15 (47) |

RV, respiratory viruses, including hRSV, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, influenza A virus, and parainfluenza viruses types 1 to 3.

Included in the total specimens examined for other respiratory viruses in each year.

Significantly different from the results for hMPV-positive samples in the years 2000 and 2002 at P = 0.004 and P = 0.0003, respectively (chi-square test).

Significantly different from the results for other respiratory virus-positive samples in the year 2000 at P = 0.038 (chi-square test).

The seasonal distribution of infection across the 3 years is consistent with the expected incidence, as 21 of 67 (31%) specimens submitted between January and May were hMPV positive, while only 2 of 23 specimens (9%) submitted between June and December were hMPV positive (Table 4). Both of these hMPV-positive samples submitted later in the year were detected in the fall of 2000, one in October and one in December.

TABLE 4.

Seasonal distribution of the 23 hMPV-positive nasal swab specimens

| Yr | Season

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January to May

|

June to December

|

|||

| Total no. of specimens tested | No. (%) positive | Total no. of specimens tested | No. (%) positive | |

| 2000 | 10 | 5 (50) | 9 | 2 (22)a |

| 2001 | 27 | 3 (11) | 14 | 0 (0) |

| 2002 | 30 | 13 (43) | NAb | NA |

| Total | 67 | 21 (31) | 23 | 2 (9) |

One sample was positive in October, and one sample was positive in December.

NA, not available.

Genetic analysis of hMPV isolates.

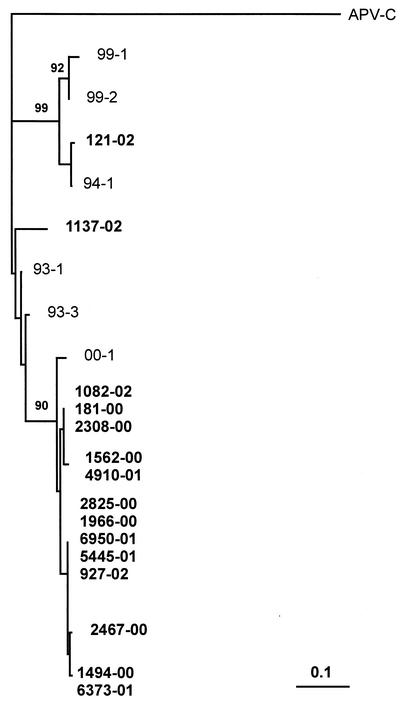

Sequencing was limited to 15 amplicons from independent PCR runs because this number was considered an appropriate sampling of the total of 23 amplicons obtained. Phylogenetic analysis showed that all but one of the isolates sequenced (isolate 121-02) were in the same hMPV group (Fig. 1). Most of the strains were very closely related, and the sequence analyzed was virtually identical for a few strains. When nasal swab and blood specimens from the same patient were analyzed phylogenetically, some small changes were noted in the isolates from three of five patients, but the viruses in both types of samples were identical in two patients (data not shown). Of interest, clustering of the isolates was independent of the patient's age or disease.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of 15 hMPV isolates from the present study. The tree is based on a 102-bp segment from the L gene of the viral genome. The branching pattern of the tree was obtained by the neighbor-joining algorithm, with randomization of the input order of sequences. Bootstrap resampling was used to test the robustness of the tree, and bootstrap values above 90% for 1,000 replicates are shown at the branch points. Genetic distances were calculated by using the Poisson correction distance (Poisson P), as provided by the DAMBE program (version 4.1.0). Nasal isolates from the present study are shown in boldface and are labeled with the year of specimen collection (last two digits). GenBank sequences are indicated by isolate name. Avian pneumovirus C (APV-C; GenBank accession number AF176591) was used as the outgroup. The bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

DISCUSSION

The recent discovery of hMPV, a new virus associated etiologically with acute human respiratory tract infections in Europe, North America, and Australia, inspired an investigation of nasal swab specimens collected from infants in Pisa, Italy (2, 7, 9, 12). This investigation confirmed that hMPV can be associated with clinical disease and extends the previous findings. Previous studies had been limited to patients who had respiratory infections for which no etiology had been detected. In the present study, nasal swab specimens were taken from children less than 2 years old with respiratory infections and were tested for the presence of hMPV as well as other respiratory viruses. Among the hMPV-positive specimens, more were isolated from infants with bronchpneumonia (14 of 23) than from infants with milder acute respiratory disease (9 of 23). This is consistent with recent reports showing a higher prevalence of hMPV in children with lower respiratory tract infections than in children with upper respiratory tract infections (1, 7). The other studies that identified hMPV in clinical specimens did not provide information on the severity of disease (9, 12). Even more interesting was the finding that many more cases of bronchopneumonia were associated with hMPV infection than infection with the other viruses (only three cases) in the absence of hMPV. It must be noted that 5 of 17 cases of bronchopneumonia were mixed infections with hMPV and other viruses, but the rate of bronchopneumonia in those infected with hMPV alone (64%) was as high as the rate of bronchopneumonia in those with mixed infections with hMPV and another virus (56%). In this regard, it should also be noted that the mixed infections recognized would most likely have been more numerous if the detection methods used for common respiratory viruses were as sensitive as the PCR assay used for hMPV detection. Thus, mixed infections do not necessarily result in more severe infection, but detection of hMPV may be a predictor of potentially more serious disease in infants. Since the previous studies did not examine specimens for hMPV if they were known to contain another virus, there is no indication of whether the rate of mixed infection in the Pisa patients is typical or unusual. Taken together, the present findings suggest that hMPV might be associated with a high rate of serious respiratory infections in hospitalized infants; however, because the number of infants studied was small, the issue clearly needs further investigation.

Earlier studies, based on the presence of anti-hMPV antibodies, indicate that by age 2 years the proportion of children with evidence of previous hMPV infection is approximately 55% and that by age 5 to 10 years the proportion is 100% (12). The detection of anti-hMPV antibodies in 100% of older children suggests that most infections are not associated with serious disease, yet data are lacking on the proportion of infections that are associated with serious disease. While the incidence in the Australian study was only 1.5%, all were associated with lower respiratory tract disease (7). In the present study, a high proportion (25%) of the infants less than 2 years old who required hospitalization for acute respiratory disease were hMPV positive, and most of these (21 of 23) had lower respiratory tract involvement. The incidence noted was somewhat higher than that noted in the studies reported previously, but the range of clinical disease was similar (2, 7, 9, 11, 12). This difference in incidence is likely related to the difference in the patient populations studied, as the other studies did not indicate that samples were limited to those from children less than 2 years old. It is probable that most hMPV infections are mild or subclinical in all age groups but that the ones that occur before age 2 may be associated with more severe disease.

Another interesting observation is that hMPV RNA was demonstrated in the plasma of 41% of patients in whom hMPV was detected in their nasal passages. This finding, although surprising, is consistent with a report on hRSV which showed that the majority of patients who had virus in their nasal washings had viral RNA in their blood (10). In that study, both types of specimens from 14 of 41 patients were positive, while the nasal washings were virus positive and the blood was negative for only 5 patients. It is unclear at present what the significance of finding hMPV in plasma implies regarding clinical disease; however, among the patients in whom virus was demonstrated in their blood, a higher percentage had serious disease. These studies must be expanded before any definitive information can be derived.

As a result of studying specimens over the course of three respiratory infection seasons, we noted a pattern in which the incidence of hMPV in this population was not consistent for the 3 years. Approximately 40% of the samples yielded hMPV RNA in 2000 and 2002, yet only 7% were positive in 2001. While this pattern of alternating years of high and low incidence is consistent with what is observed for other respiratory viruses, it is not clear if this was coincidence or a real pattern. Furthermore, when we examined the overall pattern of incidence of respiratory tract infections, we saw that the pattern for hMPV was similar to those for other respiratory viruses and hRSV, as the overall rate of positive specimens was lower in 2001. The seasonal incidence was as expected for respiratory tract infections, with 91% of hMPV-positive samples being collected from January to May, paralleling what is normally seen in Pisa for hRSV (6). The positive two specimens that were collected in the fall of 2000 may indicate the early onset of the respiratory virus season that year, which is also consistent with what is reported for hRSV in some years (6). Thus, while there is a suggestion of a cyclic pattern of occurrence of hMPV, analysis of more data from future respiratory virus seasons will need to be evaluated to establish a true pattern.

Molecular analysis of the hMPV RNA of the isolates from several of these patients indicated that the virus seen in Pisa is similar to those identified in The Netherlands and North America (9, 12). Most sequences clustered into one lineage, while one sequence was in a second cluster (Fig. 1). Previous reports indicate that there are two hMPV subgroups (9, 12, 13). This study of specimens submitted to the diagnostic virology laboratory in Pisa raises a number of provocative points based on the data collected. The incidence of infection in Pisa appears to be considerably higher than that reported in the first reports concerning this new respiratory virus, although none of those studies looked at all nasal wash specimens submitted; rather, they examined only those specimens found to be negative for other viruses. Despite the data collected in the present study, the only confirmed association of hMPV with disease causation is in an experiment with cynomolgus monkeys (12). Thus, criteria must be fulfilled to demonstrate definitively that hMPV is a cause of respiratory infection in humans. A concerted effort to study the incidence of hMPV in numerous locales is certainly warranted if the association with severe lower respiratory tract infection is to be seriously considered.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca, Rome, Italy.

We are grateful to A. D. M. E. Osterhaus for providing the nucleotide sequences of the primers used for the hMPV-specific PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boivin, G., Y. Abed, G. Pelletier, L. Ruel, D. Moisan, S. Cote, T. C. T. Peret, D. D. Erdman, and L. J. Anderson. 2002. Virological features and clinical manifestations associated with human metapneumovirus: a new paramyxovirus responsible for acute respiratory-tract infections in all age groups. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1330-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howe, M. 2002. Australian find suggests worldwide reach for metapneumovirus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2000. Family Paramyxoviridae, p. 549-561. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel, C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wicker (ed.), Virus taxonomy. Seventh Report of the Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 4.Ison, M. G., and F. G. Hayden. 2002. Viral infections in immunocompromised patients: what's new with respiratory viruses? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 15:355-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jartti, T., B. van den Hoogen, R. P. Garofalo, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, and O. Ruuskanen. 2002. Metapneumovirus and acute wheezing in children. Lancet 360:1393-1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mufson, M. A. 2000. Respiratory viruses, p. 235-251. In S. Specter, R. L. Hodinka, and S. A. Young (ed.), Clinical virology manual, 3rd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Nissen, M. D., D. J. Siebert, I. M. Mackay, T. P. Sloots, and S. J. Withers. 2002. Evidence of human metapneumovirus in Australian children. Med. J. Aust. 176:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelletier, G., P. Dery, Y. Abed, and G. Boivin. 2002. Respiratory tract reinfections by the new human metapneumovirus in an immunocompromised child. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:976-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peret, T. C. T., G. Boivin, Y. Li, M. Couillard, C. Humphrey, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, D. D. Erdman, and L. J. Anderson. 2002. Characterization of human metapneumoviruses isolated from patients in North America. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1660-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohwedder, A., O. Keminer, J. Forster, K. Schneider, E. Schneider, and H. Werchau. 1998. Detection of respiratory syncytial virus RNA in blood of neonates by polymerase chain reaction. J. Med. Virol. 54:320-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stockton, J., I. Stephenson, D. Fleming, and M. Zambon. 2002. Human metapneumovirus as a cause of community-acquired respiratory illness. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:897-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Hoogen, B. G., J. C. de Jong, J. Groen, T. Kuiken, R. de Groot, R. A. M. Fouchier, and A. D. M. E. Osterhaus. 2001. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat. Med. 7:719-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Hoogen, B. G., T. M. Bestebroer, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, and R. A. M. Fouchier. 2002. Analysis of the genomic sequence of a human metapneumovirus. Virology 295:119-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]