Abstract

Background

Phytobezoar may be a cause of bowel obstruction in patients with previous gastric surgery. Most bezoars are concretions of poorly digested food, which are usually formed initially in the stomach. Intestinal obstruction (esophageal and small bowel) caused by an occupational bezoar has not been reported.

Case presentation

A 70-year old male is presented suffering from esophageal and small bowel obstruction, caused by an occupational bezoar. The patient has worked as a carpenter for 35 years. He had undergone a vagotomy and pyloroplasty 10 years earlier. The part of the bezoar, which caused the esophageal obstruction was removed during endoscopy, while the part of the small bowel was treated surgically. The patient recovered well and was discharged on the 8th postoperative day.

Conclusions

Since occupational bezoars may be a cause of intestinal obstruction (esophageal and/or small bowel), patients who have undergone a previous gastric surgery should avoid occupational exposures similar to the presented case.

Background

Phytobezoar causing bowel obstruction in patients with previous gastric surgery is a well known late complication, although very rare. It is a concretion of food fibers (fruit and vegetable fibers) or foreign bodies in the stomach [1]. The stomach is the most common place of bezoar formation. In a normal stomach vegetable fibers can not pass through the pylorus; they undergo hydrolysis within the stomach, which softens them enough to go through the small bowel. After gastric surgery, because the gastric motility is disturbed, the gastric acidity is decreased, and the stomach may rapidly empty, there is an increased possibility for bezoar formation, causing acute abdomen due to small bowel obstruction.

Reports of bezoars causing obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract exist since the late 18th century [2]. Mir and Mir [3] reported on 22 cases of bezoar found in the literature from 1966 to 1973. Most case reports refer to bezoars of food with fibers or foreign bodies. Moseley [4] reported the first case of a phytobezoar (citrus, onions, mushrooms) following vagotomy and pyloroplasty.

There have not been incidents of occupational reason. The reverse migration of the bezoar to the esophagus is also very rare, and may occur after persistent vomiting and bezoar fragmentation [5,6]. In this paper, the case of a patient with a phytobezoar of occupational origin is presented. The patient suffered from both esophageal and small bowel obstruction.

Case presentation

A 70-year old male carpenter, who complained of dysphagia for several days, and epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting for 24 hours, was admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine. He had worked as a carpenter for 35 years, only occasionally using personal protective equipment. Ten years before the incident, he had undergone cholecystectomy, vagotomy and pyloroplasty.

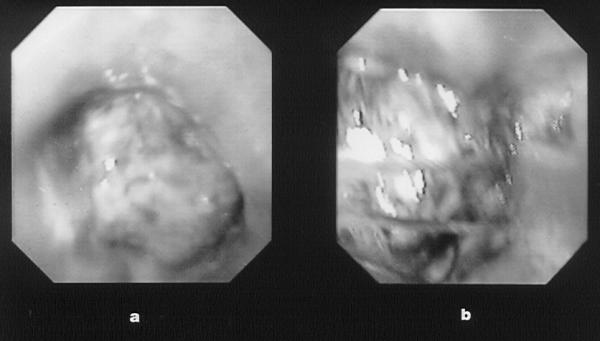

Plain x-ray and ultrasonography of the abdomen were performed after admission with no diagnosis. A chest x-ray and pulmonary function tests were normal. Vomiting continued and the dysphagia worsened. The patient then underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (using Olympus GIF-V2, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), which showed a foreign body (dimensions: 1.5 cm long, 2.8 cm in diameter), which was then endoscopically removed using a dormia basket (Fig. 1). Further endoscopic examination to the second part of the duodenum revealed no pathological findings. Pathological examination reported that the removed foreign body consisted of wood dust (Fig. 2a).

Figure 1.

Endocopy (a) obstruction of the lower third of the esophagus due to a bezoar; (b) removal of the esophageal bezoar with a Dormia-basket.

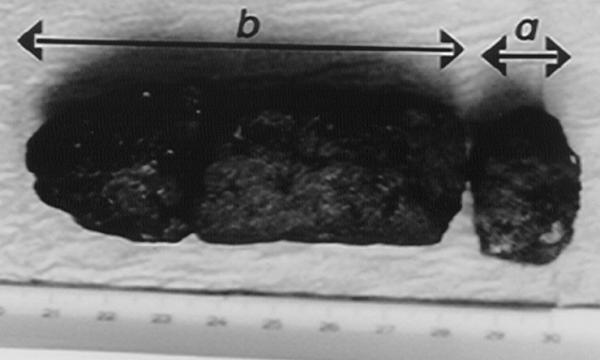

Figure 2.

The entire bezoar (a) esophageal; (b) intestinal.

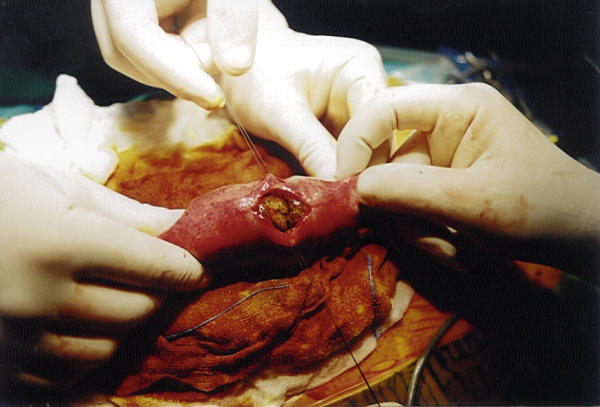

The patient's condition improved only partially after endoscopy. Few days later he developed abdominal pain and repeat x-ray of the abdomen showed dilated gas-filled loops of the small bowel with no air in the colon, suggesting small bowel obstruction. He was then transferred to the surgical clinic, where failure of a few day of conservative treatment necessitated an exploratory laparotomy. The laparotomy revealed a complete distal ileal obstruction secondary to a solid intraluminal foreign body (dimension 9.0 cm long, 2.9 cm in diameter), which was removed through an enterotomy (Figs. 3 and 4). Pathological examination of the foreign body revealed a composition similar to that removed from the esophagus (Fig. 2b). The patient was discharged on the 8th postoperative day, and has remained well at 18-month follow up.

Figure 3.

Enterotomy

Figure 4.

Removal of the intestinal bezoar

Discussion

Intestinal obstruction due to phytobezoars (food, vegetable fibers, and/or foreign bodies) is rarely encountered in adults with a normal intestinal tract. Phytobezoar usually is a cause of intestinal obstruction in patients with previous vagotomy and drainage or gastric resection [1,3,4]. Most of the bezoars that have been presented in the literature are concretions of poorly digested food, which are usually formed initially in the stomach; a fragment of them may migrate into the bowel and cause obstruction [1,2,4]. Obstruction from phytobezoars usually occurs in the ileum and the jejunum. It is unusual for reverse migration of the bezoar to the esophagus to occur and result in obstruction as occurred in our patient [5,6]. Some of the pathogenic mechanisms responsible for bezoar formation in patients with vagotomy and pyloroplasty include decreased secretion of hydrochloric acid, decreased gastric motility (atonic stomach), and occupational exposure [1,2,4].

Whilst bezoars located in the esophagus or stomach should be treated conservatively in the first instance [3], those causing acute intestinal obstruction clearly require surgical intervention [1,3,4]. In our patient the cause of the bezoar was the accumulated wood dust (occupational bezoar) in the stomach and the previous gastric surgery. The bezoar had two different final locations, one in the esophagus and the other in the small bowel. The initial mass was probably in the stomach, and due to the continuing vomiting, the bezoar was fragmented. The fragments migrated causing obstruction in two different locations in the intestinal tract. The tail of the bezoar moved to the esophagus, while the rest migrated from the stomach through the pylorus (because of the previous vagotomy and pyloroplasty) and into the small bowel. Two different therapies were used to treat this occupational phytobezoar, namely endoscopy and surgery.

To our knowledge this is the first case of an occupational bezoar consisting of wood dust. The patient only occasionally used personal protective equipment in his work, and during the month before the incident, he had worked around twelve hours per day. The use of personal protective equipment is imperative to avoid serious health problems to the workers.

In conclusion, since occupational bezoars may be a cause of intestinal obstruction (esophageal and/or small bowel), patients who have undergone a previous gastric surgery should avoid certain kinds of fiber in their diet (e.g., fruit, usually citrus, and vegetable fibers), and are advised to take protective measures against similar occupational exposures (e.g., wood dust).

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient for giving us written consent for publishing this study.

Contributor Information

Michail Pitiakoudis, Email: mpitiak@med.duth.gr.

Alexandra Tsaroucha, Email: tsihrin@otenet.gr.

Konstantinos Mimidis, Email: mpitiak@med.duth.gr.

Theodoros Constantinidis, Email: tconstan@med.duth.gr.

Stavros Anagnostoulis, Email: atsarouc@med.duth.gr.

George Stathopoulos, Email: stathg@otenet.gr.

Constantinos Simopoulos, Email: simop@med.duth.gr.

References

- Rubin M, Shimonov M, Grief F, Rotestein Z, Lelkuk S. Phytobezoar: a rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Dig Surg. 1998;15:52–54. doi: 10.1159/000018586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madura MJ, Naughton BJ, Craig RM. Duodenal bezoar: a report case and review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1982;28:26–28. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(82)72964-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir AM, Mir MA. Phytobezoar after vagotomy with drainage or resection. Brit J Surg. 1973;60:846–847. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800601103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley RV. Pyloric obstruction by a phytobezoar following pyloroplasty and vagotomy: report of a case. Arch Surg. 1967;94:290–291. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330080128031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermoso JC, Rosado R, Ramirez D, Ruiz JJ, Medina P, Bonetti A. A esophageal impaction of a bezoar after gastric surgery. Rev Esp Enf Digest. 1991;79:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel AL, Seenu V, Srikrishna NV, Goyal S, Thakur KK, Shukla NK. Esophageal bezoar: a rare but distinct clinical entity. Trop Gastroenterol. 1995;16:43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]