Abstract

The BayGenomics gene-trap resource (http://baygenomics.ucsf.edu) provides researchers with access to thousands of mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell lines harboring characterized insertional mutations in both known and novel genes. Each cell line contains an insertional mutation in a specific gene. The identity of the gene that has been interrupted can be determined from a DNA sequence tag. Approximately 75% of our cell lines contain insertional mutations in known mouse genes or genes that share strong sequence similarities with genes that have been identified in other organisms. These cell lines readily transmit the mutation to the germline of mice and many mutant lines of mice have already been generated from this resource. BayGenomics provides facile access to our entire database, including sequence tags for each mutant ES cell line, through the World Wide Web. Investigators can browse our resource, search for specific entries, download any portion of our database and BLAST sequences of interest against our entire set of cell line sequence tags. They can then obtain the mutant ES cell line for the purpose of generating knockout mice.

INTRODUCTION

BayGenomics is a consortium of research groups in the San Francisco Bay Area funded through the NHLBI ‘Programs for Genomic Applications’ (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/pga). The major goal of BayGenomics is to identify genes relevant to cardiovascular and pulmonary development and disease. The mouse has already proven to be a useful model for understanding mammalian genetics and mammalian physiology. Nearly all the genes in mice have identifiable orthologs in humans (1) and thus the genetic analysis of genes in mice is a highly effective tool for studying the functions of human genes and their roles in human disease. One method for the functional analysis of genes in mice is gene-trapping (2). Studies with our gene-trap vector designs show the methodology to be an efficient tool for the mutational analysis of genes in mice (3, unpublished results). The method is particularly well-suited to the study of novel genes, with access to a large pool of never-before studied ‘unnamed genes’ that are expressed during all stages of development.

BayGenomics is using a combination of secretory and non-secretory gene-trap vectors to inactivate thousands of genes in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells for the purpose of generating knockout mice. These ES cell mutants are freely available to the research community on a non-collaborative basis. Many of these insertional mutants have already been transmitted through the germline, both in our laboratories and in many other laboratories around the world.

To facilitate and promote the distribution of our gene-trap resource to outside investigators, we have developed a computerized database containing the sequences and annotations of thousands of gene-trapped mouse embryonic stem cell lines (http://baygenomics.ucsf.edu). Approximately 75% of the ES cell lines contain insertional mutations in identified mouse genes or in mouse genes that appear to be homologous to genes identified in other organisms. Our goal is to identify the mouse genes associated with 10 000 insertional mutations in embryonic stem cells by January 2004.

THE RESOURCE

The BayGenomics resource is built around our mouse cell lines. We are using a variety of gene-trap vector designs to access all classes of protein-coding genes. The vectors include secretory and nonsecretory trap vectors engineered in each of three possible reading frames. Gene-trap vectors contain a splice-acceptor sequence upstream of a reporter gene (typically β geo, a fusion of β-galactosidase and neomycin phosphotransferase). The insertion creates a fusion transcript that joins the sequences from exons 5′ to the insertion site to the β-galactosidase marker. Thus, in any mouse generated from our ES cell lines, it is possible to use β-galactosidase expression to document the temporal and spatial pattern of gene expression. The identity of each ‘trapped’ gene is determined by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) followed by automated DNA sequencing (4).

DNA sequencing is performed by UCSF's Genomics Core Facility (GCF). The GCF deposits the chromatogram data (‘trace’ files) onto a computer for downloading, which sets in motion a multi-step automated process of data retrieval, analysis and storage. This process is driven by programs written in Python, an open-source, object-oriented programming language well suited for rapid development in research environments where the goals and demands tend to evolve quickly (http://www.python.org). All data is stored in MySQL, an open-source relational database system (http://www.mysql.com).

The automated base-calling program Phred (5,6) is used to interpret the chromatogram files. The resulting base calls are trimmed using a base-quality cutoff of 14.6. (This value has been empirically determined to provide better results for our experimental protocol than Phred's default quality cutoff of 30.0.) Reverse complements of the resulting sequences are generated in order to obtain the sense strand of each sequence tag. Not every insertion results in proper splicing. We discard cell lines in which the sequence tag contains unspliced sequences or spliced sequences containing vector-encoded intronic sequence upstream of the splice acceptor site.

As a consequence of the 5′ RACE reaction, there is typically a consecutive run of Ts at the 5′ end of the sequence tags. We remove any poly-T tail greater than seven Ts in length. Gene trap vector sequences are also automatically removed from sequence tags. We retain both the original sequence and the resulting ‘cleaned’ sequence in the database. Cell line sequences with less than 20 bases remaining after ‘cleaning’ are discarded. The remaining sequences are further processed using our automated annotation protocol.

AUTOMATED ANNOTATION PROTOCOL

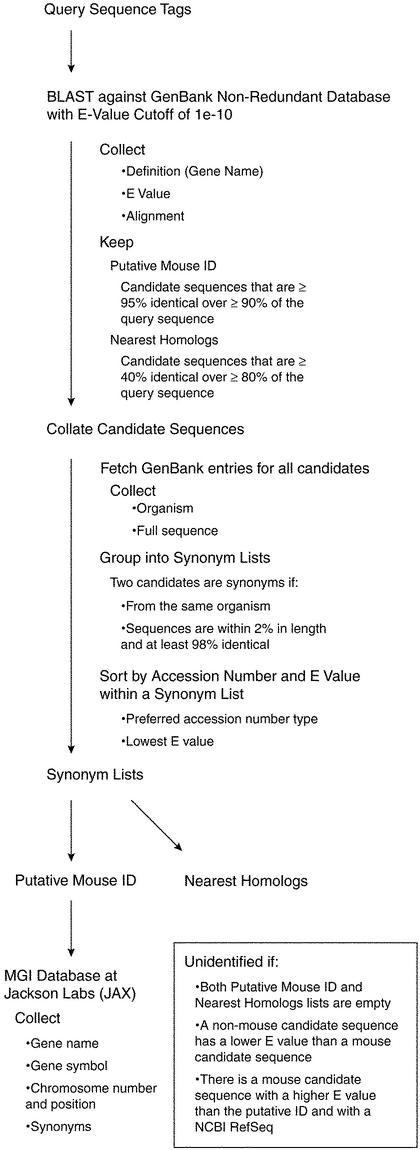

Each sequence tag is queried via BLAST (7) against the NCBI non-redundant (nr) sequence database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/html/blastcgihelp.html). BLAST search outputs are limited to an E-value cutoff of 1e-10, with the number of reported sequences limited to 50.

BLAST outputs are parsed to collect names, E values, and alignments against the query sequence for all the candidate sequences (Fig. 1). We align each candidate sequence against the query sequence. We then determine the longest ‘consecutive’ run of aligned bases, allowing gaps of up to two bases. Candidate sequences that are at least 95% identical to a query sequence, over at least 90% of the query sequence are designated as Putative Mouse IDs. This stringent criterion ensures that sequences in this category have a very high likelihood of corresponding to an identified gene.

Figure 1.

A schematic of our automated protocol for annotating cell line sequence tags.

Some of the sequence tags do not correspond clearly to a mouse sequence but do correspond to sequences of genes that have been identified in other species (e.g. humans, flies, or worms). These sequences are categorized as Nearest Homologs. These sequences adhere to the more relaxed criteria of at least 40% base identity over a contiguous sequence covering at least 80% of the cell line tag sequence. This category represents our current best attempt at identifying the nearest homolog to the sequence in question using an automated protocol. We advise investigators to use caution when interpreting the genes identified in this category and to carefully inspect the sequence tag before requesting the ES cell line or otherwise using the sequence information.

Candidate sequences are then grouped into lists of synonyms. Two candidate sequences are synonyms if they are from the same organism, are within 2% in length, and are at least 98% identical. Within each synonym list, candidates are ranked into five groups of GenBank sequence types, as indicated by accession number prefix. The five groups, in descending priority, are: (1) curated mRNAs (NM), (2) model mRNAs corresponding to genomic contigs (XM), (3) any sequence type not explicitly assigned, (4) chromosomes and complete genomes (NC) and (5) constructed genomic contigs (NT). The highest priority sequence type within the list is assigned as the accession number for that list. The lowest E value within a synonym list is assigned as the E value for the list.

Unidentified sequences are those sequences that do not meet the criteria described above. We periodically rerun all of our sequence tag data through our annotation protocol in order to match existing sequence tags with newly annotated sequences in GenBank. From time to time, our gene-identification protocols are refined. This may result in particular sequence tags moving from one category to another even though the underlying sequence tag data have not changed.

RESOURCE INTERFACE

We have developed a web site, http://baygenomics.ucsf.edu, to provide access to our database. The web site provides four entry points for accessing our sequence tag data: browse, search, download and BLAST. To browse, a user can choose among the three identification categories listed above—Putative Mouse ID, Nearest Homolog and Unidentified—though all three are available from every browse results page. The user can sort by gene name, standard mouse gene symbol (Mouse Genome Informatics Database at the Jackson Laboratory http://www.informatics.jax.org), cell line name, chromosome number, or by the availability of in situ hybridization images (see below). By default, the form will return all entries in the database, divided into pages of 25 entries each, with each page presented in a table format. The user can choose to see all entries on one page or select from several intermediate values. It is also possible to limit the browse list to include only those cell line entries that were created or have been updated since a specified date.

It is well known that gene expression patterns are closely associated with their functions. As an important step toward understanding the functions of the genes in our gene-trap resource, we perform in situ hybridization studies (8) to localize mRNAs in a spatially and temporally specific manner. We obtained IMAGE clones (9, http://image.llnl.gov) corresponding to genes inactivated in the gene-trap studies and generate digoxigenin and/or 33P-labeled probes. These probes are used to analyze wild-type mouse embryos at different developmental stages, as well as heart and lung from both wild-type mice and mice with cardiopulmonary diseases. Mouse embryo tissue is processed, embedded and sectioned in a variety of ways to produce paraffin sections for examination. High-resolution in situ hybridization images are then captured, processed, annotated and deposited in the BayGenomics database. Low resolution ‘thumbnail’ versions of these images may be browsed directly if desired. Each thumbnail represents a high-quality tagged-image file format (TIFF) image that can be downloaded to an investigator's desktop computer for detailed examination. The expression patterns found in these images are often informative of gene function.

The second access entry point to our sequence tag data is the search page, which presents an interface similar to that of the browse interface. Search categories include cell line identifier, GenBank identifier, gene name, chromosome number, standard mouse gene symbol and vector name. Searching by GenBank identifier does not require the user to supply the same accession number stored in our database. Instead, when the number requested is not found, the corresponding sequence is automatically retrieved from GenBank and BLASTed against our identified gene sequences to retrieve the correct gene record.

Both browse and search access methods return a table associating cell lines to gene identifications. This table lists gene names, standard mouse gene symbols, chromosome numbers, centimorgan positions and cell line names. Links are included to our in situ hybridization images, when available. Links are also included to separate annotation pages for cell lines and genes.

The cell line annotation page contains the sequence used for identification and the gene-trap vector. The best identification made by our automated protocol is shown, as is the percentage identity and maximum alignment run length. This page also includes species, standard mouse gene symbol, GenBank identifier, chromosome number and centimorgan position. Links are provided to the appropriate annotation pages in the Mouse Genome Database (10) and GenBank. The gene annotation page provides similar information, as well as a list of synonyms and links to all cell lines matching the gene identification. If in situ hybridization images exist, a link is also provided to these images.

Downloading is the third data access method. Researchers may download data in our resource to desktop computers and conduct their own analysis. Either all cell line sequences or only those posted or updated since a specified date may be easily downloaded in FASTA format. A separate, advanced download page provides access to the entire BayGenomics database. Here, researchers may download a table of tab-delimited text simply by selecting data fields of interest. The amount of data retrieved may be further controlled through various drop-down date fields.

The fourth and final data access entry point is BLAST. Every cell line sequence is automatically incorporated into a local ‘blastable’ database. Researchers who have a gene sequence of interest can compare it directly against our cell line sequences using a version of BLAST integrated into our web site.

STATUS

Our resource contains over 5300 cell line sequence tags and is growing, with new cell lines deposited nearly every week. We are also working to develop additional identification protocols in an effort to identify a greater percentage of our sequence tags. Enriched annotation, including references to the literature and protein family assignments, is under development. We anticipate that this resource will be of great value to any biologist interested in using knockout mice to define gene function and to understand the genetic basis of human disease.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

BayGenomics is a Program for Genomic Applications (PGA) sponsored by NHLBI to advance functional genomic research related to heart, lung, blood and sleep health and disorders. Our research is supported by NIH NHLBI U01 HL66621 and NIH NCRR P41 RR01081.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mural R.J., Adams,M.D., Myers,E.W., Smith,H.O., Gabor Miklos,G.L., Wides,R., Halpern,A., Li,P.W., Sutton,G.G., Nadeau,J. et al. (2002) A comparison of whole-genome shotgun-derived mouse chromosome 16 and the human genome. Science, 296, 1661–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanford W.L., Cohn,J.B. and Cordes,S.P. (2001) Gene-trap mutagenesis: past, present and beyond. Nature Rev. Genet., 2, 756–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell K.J., Pinson,K.I., Kelly,O.G., Brennan,J., Zupicich,J., Scherz,P., Leighton,P.A., Goodrich,L.V., Lu,X., Avery,B.J., Tate,P., Dill,K., Pangilinan,E., Wakenight,P., Tessier-Lavigne,M. and Skarnes,W.C. (2001) Functional analysis of secreted and transmembrane proteins critical to mouse development. Nature Genet., 28, 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townley D.J., Avery,B.J., Rosen,B. and Skarnes,W.C. (1997) Rapid sequence analysis of gene trap integrations to generate a resource of insertional mutations in mice. Genome Res., 7, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewing B., Hillier,L., Wendl,M.C. and Green,P. (1998) Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using Phred. I. Accuracy Assessment. Genome Res., 8, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewing B. and Green,P. (1998) Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using Phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res., 8, 186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altschul S.F., Gish,W., Miller,W., Myers,E.W. and Lipman,D.J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkinson D.G. and Nieto,M.A. (1993) Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods Enzymol., 225, 361–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lennon G.G., Auffray,C., Polymeropoulos,M. and Soares,M.B. (1996) The IMAGE consortium: an integrated molecular analysis of genomes and their expression. Genomics, 33, 151–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blake J.A., Richardson,J.E., Bult,C.J., Kadin,J.A., Eppig,J.T. and the Mouse Genome Database Group (2002) The Mouse Genome Database (MDG): The Model Organism Database for the Laboratory Mouse. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 113–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]