Abstract

The membrane protein DsbB from Escherichia coli is essential for disulfide bond formation and catalyses the oxidation of the periplasmic dithiol oxidase DsbA by ubiquinone. DsbB contains two catalytic disulfide bonds, Cys41–Cys44 and Cys104–Cys130. We show that DsbB directly oxidizes one molar equivalent of DsbA in the absence of ubiquinone via disulfide exchange with the 104–130 disulfide bond, with a rate constant of 2.7 × 10 M–1 s–1. This reaction occurs although the 104–130 disulfide is less oxidizing than the catalytic disulfide bond of DsbA (Eo′ = –186 and –122 mV, respectively). This is because the 41–44 disulfide, which is only accessible to ubiquinone but not to DsbA, is the most oxidizing disulfide bond in a protein described so far, with a redox potential of –69 mV. Rapid intramolecular disulfide exchange in partially reduced DsbB converts the enzyme into a state in which Cys41 and Cys44 are reduced and thus accessible for reoxidation by ubiquinone. This demonstrates that the high catalytic efficiency of DsbB results from the extreme intrinsic oxidative force of the enzyme.

Keywords: disulfide bond formation/DsbA/DsbB/redox potential/ubiquinone

Introduction

Oxidative protein folding in Escherichia coli requires a network of specialized electron transfer catalysts (Collet and Bardwell, 2002; Sevier and Kaiser, 2002; Kadokura et al., 2003). The dithiol oxidase DsbA represents the generic oxidant of reduced, folding polypeptides in the periplasm (Bardwell et al., 1991) and transfers its reactive disulfide bond extremely rapidly to reduced polypeptides (Wunderlich et al., 1993; Zapun and Creighton, 1994; Darby and Creighton, 1995). The active-site disulfide in DsbA has a redox potential of –0.122 V and is the most oxidizing disulfide bond described so far in a protein (Wunderlich and Glockshuber, 1993; Zapun et al., 1993). Upon oxidation of substrates, DsbA becomes reduced and is recycled as an oxidant through oxidation by ubiquinone Q8 under aerobic conditions. This reaction is catalysed by the inner membrane protein DsbB (Bardwell et al., 1993; Dailey and Berg, 1993; Missiakas et al., 1993; Kobayashi et al., 1997; Bader et al., 1998, 1999, 2000; Kobayashi and Ito, 1999). DsbB (176 residues) is predicted to have four transmembrane α-helices and two loops segments protruding into the periplasm. Each of the predicted loops contains two cysteines that can form a disulfide bond (cysteine pairs 41–44 and 104–130, respectively), and all four cysteines are essential for the activity of DsbB in vivo (Jander et al., 1994; Guilhot et al., 1995; Kishigami et al., 1995; Kishigami and Ito, 1996; Kobayashi and Ito, 1999).

Substantial efforts have recently been made to unravel the catalytic mechanism of the enzyme. A first model for the mechanism of DsbB was presented by Ito and coworkers (Kishigami et al., 1995; Kishigami and Ito, 1996; Inaba and Ito, 2002), according to which ubiquinone directly generates a disulfide bond (41–44) in the first periplasmic loop of DsbB, which can then be transferred to the Cys104–Cys130 pair in the second loop. The 104–130 disulfide then directly oxidizes reduced DsbA by disulfide exchange. However, both the 41–44 and 104–130 disulfides of DsbB were reported to be significantly more reducing than DsbA (–0.210 and –0.250 V, respectively). Consequently, catalysis of electron transfer from reduced DsbA to ubiquinone would have to proceed against a redox gradient in DsbB. In order to obtain the redox potentials of the disulfide bonds of DsbB, variants in which either the 41–44 or 104–130 cysteine pair was replaced by a pair of serines (variants SSCC and CCSS, respectively) were equilibrated with mixtures of cysteine and cystine. The equilibria were quenched by acid precipitation of DsbB variants with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and free thiols were trapped with 4-acetamido-4′maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (AMS) and quantified by SDS–PAGE based on the lowered electrophoretic mobility of AMS-modified protein (Inaba and Ito, 2002).

In a parallel study, Regeimbal and Bardwell (2002) measured even more reducing redox potentials for the 41–44 and 104–130 disulfide bonds of DsbB (–0.271 and –0.284 V, respectively), using the same AMS modification technique and the same DsbB variants. Moreover, they found that oxidation of DsbA by ubiquinone in vitro was also mediated by a DsbB variant (SSSS), in which all cysteines were replaced by serines. This indicated that DsbB may bring reduced DsbA and ubiquinone into close proximity, thereby allowing direct electron transfer from DsbA to ubiquinone without disulfide exchange.

Finally, a third model was suggested that again assumes disulfide exchange between DsbA and DsbB. Kadokura and Beckwith (2002) proposed that the reaction between reduced DsbA and oxidized DsbB is trapped at the level of a mixed disulfide intermediate, between Cys30 of DsbA and Cys104 of DsbB, unless ubiquinone is present. In addition, they proposed that an inter-loop disulfide between Cys41 and Cys130 in DsbB is simultaneously formed in this mixed disulfide intermediate. Again, TCA precipitation followed by AMS modification was used to monitor redox states and the occurrence of mixed disulfides.

In the present work, we analysed the mechanism of DsbB using different experimental techniques. First, in contrast to all previous in vitro studies with DsbB (Inaba and Ito, 2002; Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002), we used DsbB preparations completely depleted of bound ubiquinone Q8. Secondly, we used fluorescence spectroscopy to follow the redox state DsbB directly in solution, so that denaturing precipitation and chemical modification steps were avoided. We demonstrated that wild-type DsbB is intrinsically more oxidizing than DsbA due to an extremely oxidizing disulfide between Cys41 and Cys44. Our data exclude both direct oxidation of DsbA by ubiquinone and significant accumulation of mixed DsbA–DsbB disulfides in the catalytic cycle of DsbB.

Results

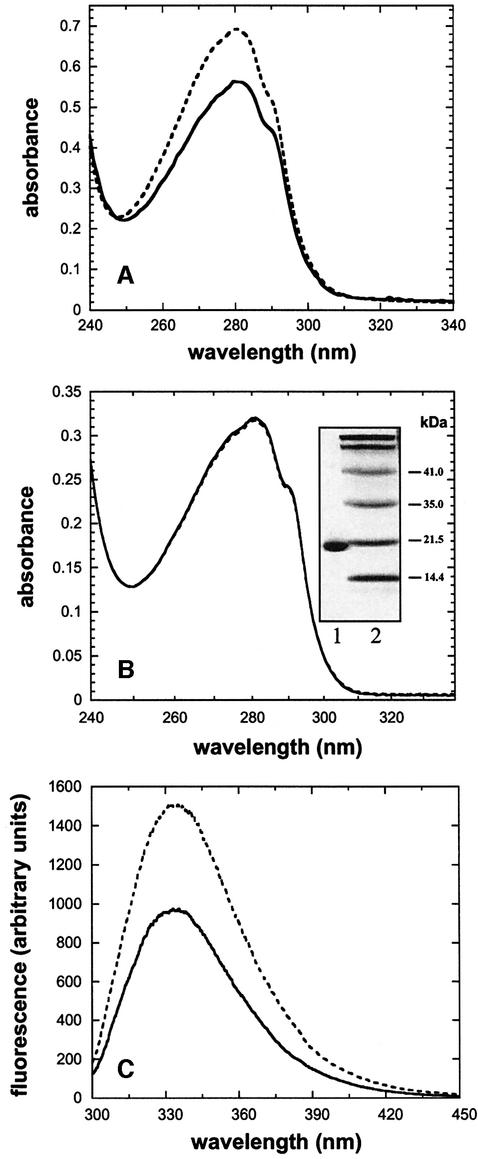

Preparation of ubiquinone-free DsbB

Thus far, all in vitro studies of the mechanism of DsbB have been performed with DsbB preparations containing up to 0.7 molar equivalents of the natural substrate ubiquinone Q8 (Inaba and Ito, 2002; Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002). We reasoned that preparation of ubiquinone-free DsbB would be essential to establish the stoichiometries of individual reaction steps in the reaction cycle of DsbB, and to distinguish pure disulfide exchange reactions between DsbB and DsbA from those between DsbA and ubiquinone. For the present study we used a DsbB protein with a C-terminal His6-tag in which the two non-essential cysteines were exchanged (Cys8→Ser and Cys49→Val; Jander et al., 1994). This variant retains full enzymatic activity (Bader et al., 1999) and is referred to as ‘wild-type’ DsbB throughout this study. DsbB was overproduced in E.coli and purified from the membrane fraction by chromatography on Ni-NTA agarose and hydroxyapaptite, in the presence of dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DM) as described previously (Bader et al., 2000). The presence of bound ubiquinone Q8 in the DsbB preparation was evident from a decrease in the absorbance at 280 nm after reduction of ubiquinone by sodium borohydride (Figure 1A). In contrast, complete removal of ubiquinone could be achieved when Ni-NTA-bound DsbB was subjected to an additional washing step with lauroylsarcosine, as shown by identical absorbance spectra before and after the addition of sodium borohydride (Figure 1B). Treatment of ubiquinone-free DsbB with Ellman’s reagent revealed the absence of free thiol groups, indicating that both catalytic disulfide bonds of DsbB were formed (data not shown). Purified wild-type DsbB was fully active as a catalyst of DsbA oxidation by ubiqinone Q1, with a kcat/KM of 4.5 × 10 M–1 s–1 (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Spectroscopic characterization of DsbB at pH 7.0 and 25°C. (A) UV spectrum of DsbB purified according to Bader et al. (2000), before (broken line) and after (solid line) reduction of bound ubiquinone Q8 by NaBH4. (B) UV spectrum of DsbB purified according to the present protocol, which includes an additional detergent wash step to remove ubiquinone Q8, before (broken line) and after (solid line) the addition of NaBH4. (Inset) Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained SDS gel: lane 1, purified DsbB; lane 2, molecular mass standard. (C) Fluorescence spectrum of ubiquinone-free, wild-type DsbB (2 µM) in 0.1% (w/v) DM at pH 7.0 before (solid line) and after (broken line) reduction of both disulfide bonds by DTT (170 µM).

Replacement of any of the disulfide bonds in DsbB eliminates substrate turnover

As a prerequisite for analysing the role of the disulfide bonds 41–44 and 104–130 in the catalytic cycle of DsbB, we purified the DsbB variants SSCC, CCSS and SSSS, in which either Cys41 and Cys44, Cys104 and Cys130, or all four cysteines, respectively, were replaced by serines. The variants SSCC and CCSS were also obtained fully oxidized and free of ubiquinone. In contrast to wild-type DsbB, all three variants proved to be inactive as catalysts of DsbA oxidation by ubiquinone and showed no substrate turnover (Supplementary figure 1, available at The EMBO Journal Online).

DsbB shows a strong fluorescence increase upon reduction of the 41–44 disulfide bond

DsbB has previously been reported to show no redox state-dependent fluorescence change (Inaba and Ito, 2002). We could not confirm this result and found that oxidized, wild-type DsbB exhibits a 1.5-fold increase in tryptophan fluorescence at 330 nm upon reduction of both disulfide bonds by dithiothreitol (DTT) (Figure 1C). Complete reduction was verified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry after quantitative modification of all four cysteines with iodoacetamide (IAM) (Table I), and by Ellman’s assay after removal of excess DTT by gel filtration (data not shown). When the oxidized DsbB variants CCSS and SSCC were reduced with DTT, a fluorescence increase at 330 nm, similar to that of the wild type, was observed for the CCSS variant, while the variant SSCC proved to be spectroscopically silent (see Figure 2A; data not shown). This indicated that the fluorescence increase observed in wild type DsbB is only caused by reduction of the 41–44 disulfide bond.

Table I. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of wild-type DsbB after modification by IAM and NEM in different redox states.

| Redox state | Modification | Measurede |

Calculated |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average mass(Da) | Δ average massf(Da) | Average mass(Da) | Δ average mass(Da) | ||

| Oxidizeda | 4 cysteines involved in disulfide bonds,no modifications | 21 047 | – | 21 002 | – |

| Partially reducedb | 2 cysteines modified by IAM | 21 154 | 107 | 21 118 | 116 |

| Fully reducedc | 2 cysteines modified by IAM,2 cysteines modified by NEM | 21 413 | 366 | 21 370 | 368 |

| Fully reducedd | 4 cysteines modified by IAM | 21 262 | 215 | 21 234 | 232 |

aWild-type DsbB in 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 7.0, 1 mM GSSG.

bWild-type DsbB in 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 7.0, 1 mM GSSG, 3 mM GSSG ([GSH]2/[GSSG] = 0.003 M) (see arrow in Figure 2B) and modified by IAM.

cWild-type DsbB treated as in b, dialysed against 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 7.0, reduced by DTT and modified by excess NEM.

dWild-type DsbB reduced by DTT and modified by IAM.

eMeasured masses were ∼40 Da higher than calculated values in all experiments.

fDifference between the measured masses of modified and oxidized DsbB.

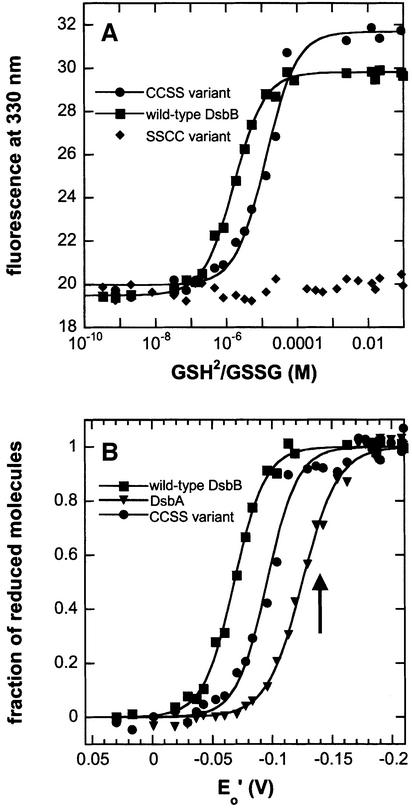

Fig. 2. Redox equilibria with glutathione of wild-type DsbB, the CCSS variant, the SSCC variant, and wild-type DsbA in 0.1% DM at pH 7.0 and 25°C. Proteins (1 µM) were incubated in the presence of 1 mM GSSG and varying concentrations of GSH (0.2 µM to 11 mM), and tryptophan fluorescence at 330 nm was recorded. (A) Original fluorescence data obtained for wild-type DsbB (squares), CCSS (circles) and SSCC (diamonds). Data for wild-type DsbB and the CCSS variant were fitted according to equation 1 (see Materials and methods) (solid lines). (B) Normalized equilibrium data, showing the fractions of partially and fully reduced wild-type DsbB (squares), reduced CCSS (circles) and reduced wild-type DsbA (triangles) under different redox conditions.

The redox potential of the 41–44 disulfide bond of wild-type DsbB is strongly oxidizing

We used the redox-state-dependent fluorescence at 330 nm of wild-type DsbB to determine the intrinsic redox properties of the 41–44 disulfide bond. We equilibrated the protein with different glutathione redox buffers (Figure 2A and B) and detected a single transition with an equilibrium constant (Keq) of 1.7 ± 0.1 × 10–6 M, corresponding to a redox potential (Eo′) of –0.069 V. Thus, the 41–44 disulfide bond of DsbB, which has been reported to be sterically inaccessible to DsbA and to interact directly with ubiquinone (Guilhot et al., 1995; Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002), is far more oxidizing than the catalytic disulfide of DsbA (Eo′ = –0.122 V; Figure 2B). Analogous redox equilibria measured with the CCSS variant (Figure 2A and B) confirmed that the 41–44 disulfide bond of DsbB is more oxidizing than DsbA, even though the CCSS variant shows a slightly lower redox potential than wild-type DsbB (Eo′ = –0.096 V; Keq = 1.3 ± 0.2 × 10–5 M) (Figure 2A and B). The SSCC variant showed no fluorescence change within the same range of redox conditions (Figure 2A).

We next determined the stoichiometry of the reduction of wild-type DsbB at a [GSH]2:[GSSG] ratio of 3.3 × 10–4 M (arrow in Figure 2B), i.e. under conditions where the reduction of the 41–44 disulfide is completed. The equilibrium was quenched by IAM, and the number of alkylated thiols in DsbB was analysed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Table I). We observed modification of only two out of the four cysteines in wild-type DsbB (Table I). As all four thiols in the fully reduced DsbB are accessible to IAM (Table I), this demonstrates that the fluorescence transition observed for wild-type DsbB corresponds to the reduction of only one disulfide bond, and that the 104–130 disulfide is significantly more reducing than the 41–44 disulfide. This was confirmed by reduction of the remaining disulfide bond in double-alkylated DsbB by DTT, and subsequent modification by N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (Table I).

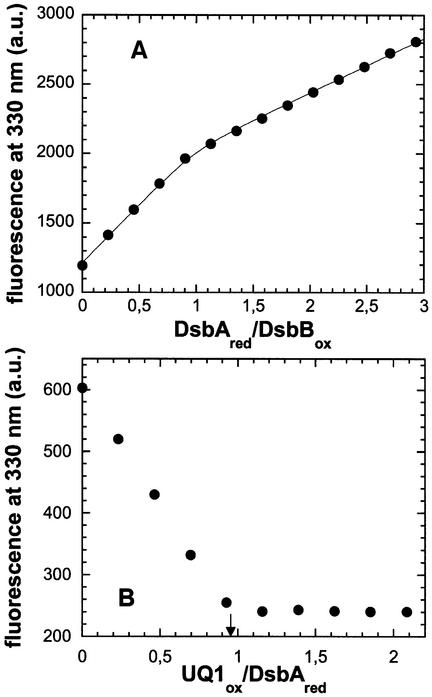

DsbB oxidizes DsbA with a 1:1 stoichometry

We simulated the reaction equilibrium between oxidized wild-type DsbB and reduced DsbA with the known redox potentials of DsbA and the 41–44 disulfide bond of DsbB, assuming different redox potentials for the 104–130 disulfide, the existence of inter-loop disulfide exchange in DsbB, and exclusive disulfide exchange between DsbA and the 104–130 disulfide. Analysis revealed that oxidized DsbB was capable of oxidizing one molar equivalent of DsbA, even if the 104–130 disulfide was strongly reducing (Supplementary figure 2). Figure 3A shows a fluorescence titration experiment at 330 nm in which oxidized DsbB was mixed with increasing quantities of reduced DsbA. DsbA exhibits a 3-fold decrease in fluorescence upon oxidation (Wunderlich and Glockshuber, 1993; Zapun et al., 1993). This fluorescence decrease is, however, smaller compared with the fluorescence increase of DsbB upon reduction of the 41–44 disulfide. We concluded that the initial fluorescence increase observed in the titration profile (Figure 3A) reflected the reduction of the 41–44 disulfide bond in DsbB and the simultaneous oxidation of DsbA. At DsbA/DsbB ratios above 1:1, the fluorescence increase originates from the increasing concentration of reduced DsbA. No further change in specific fluorescence was observed at DsbA/DsbB ratios greater than 2:1. Thus, only one molecule of DsbA can be oxidized by DsbB in the absence of ubiquinone, confirming the more reducing redox potential of the 104–130 disulfide bond of DsbB relative to DsbA. When we mixed the oxidized CCSS variant with reduced DsbA, no reaction could be observed (data not shown). This is consistent with steric hindrance of disulfide exchange between DsbA and the 41–44 disulfide in DsbB, and confirms exclusive interaction between DsbA and the 104–130 disulfide of DsbB (Guilhot et al., 1995; Kishigami and Ito, 1996). As control, we verified the 1:1 stoichiometry of the DsbB-catalysed oxidation of DsbA (Eo′ = –0.122 V) by ubiquinone (Eo′ = +0.113 V) in a DsbA fluorescence titration experiment with ubiquinone Q1 (Figure 3B). Direct oxidation of DsbA by ubiquinone Q1 in the absence of DsbB was not detected (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Fluorescence titrations in 0.1% (w/v) DM at pH 7.0 and 25°C, establishing the stoichiometry of the oxidation of DsbA by wild-type DsbB, and the DsbB-catalysed oxidation of DsbA by ubiquinone Q1. (A) Titration of oxidized DsbB (1 µM) with reduced DsbA. Fluorescence at 330 nm (circles) is plotted against the DsbA:DsbB ratio. The solid line describes a fit according to equation 3 (see Materials and methods) with an equilibrium constant of 62, corresponding to the difference in redox potential between DsbA and the 41–44 disulfide of DsbB. (B) Reduced DsbA (1 µM) was mixed with catalytic amounts (20 nM) of oxidized wild-type DsbB and titrated with a solution of ubiquinone Q1. Fluorescence at 330 nm (circles) is plotted against the UQ1:DsbAred ratio. The arrow at UQ1:DsbAred = 0.96 indicates the equivalence point of the titration.

Determination of the redox potential of the 104–130 disulfide bond in DsbB

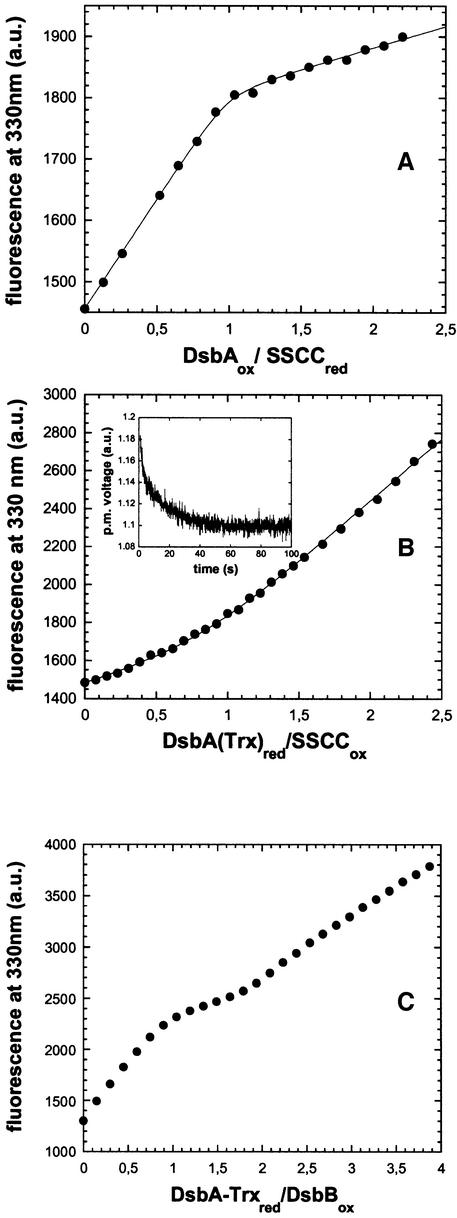

As the 104–130 disulfide bond is spectroscopically silent upon reduction and interacts directly with DsbA, we used DsbA instead of glutathione as reference redox partner to determine the redox potential of the 104–130 disulfide. As the 104–130 disulfide proved to be more reducing than DsbA, we first performed a titration experiment in which the reduced SSCC variant (1 µM) was oxidized by DsbA. This is the reverse reaction of that occurring in the catalytic cycle of DsbB. The titration profile (Figure 4A) is characterized by a sharp kink at a DsbA:SSCC ratio of 1:1, where the linear slopes before and after the kink correspond to the specific fluorescence of reduced and oxidized DsbA, respectively. The sharp kink shows that the SSCC variant is significantly more reducing than DsbA. In order to obtain an accurate value for the redox potential of the 104–130 disulfide, we searched for a more reducing DsbA variant with redox properties more similar to those of the 104–130 disulfide. We selected the variant DsbA–Trx, in which the dipeptide between the active-site cysteines was replaced by that of thioredoxin. DsbA–Trx is significantly more reducing (Eo′ = –0.214 V) than wild-type DsbA and also shows a fluorescence increase upon reduction (Huber-Wunderlich and Glockshuber, 1998). When we mixed stoichiometric amounts (0.5 µM each) of reduced DsbA–Trx with the oxidized SSCC variant of DsbB, we observed very rapid and almost quantitative oxidation of DsbA–Trx (Figure 4B, insert) with a second-order rate constant of 3.3 ± 0.2 × 10 M–1 s–1 and a half time of 6 s, demonstrating that the redox potential of the 104–130 disulfide lies between –0.122 and –0.214 V.

Fig. 4. Determination of the redox potential of the 104–130 disulfide bond in the SSCC variant of DsbB at pH 7.0 and 25°C in 0.1% (w/v) DM by fluorescence titration. (A) Wild-type DsbA oxidizes the 104–130 disulfide in the SSCC variant. The reduced SSCC variant (1 µM) was titrated with oxidized wild-type DsbA, and the fluorescence at 330 nm (circles) was plotted against the DsbA:SSCC ratio. Data were fitted (solid line) according to equation 3 and were consistent with a calculated equilibrium constant of 146 (Supplementary table I). (B) Redox equilibrium between the SSCC variant and DsbA–Trx. The oxidized SSCC variant (1 µM) was titrated with reduced DsbA–Trx. The fluorescence at 330 nm (circles) was plotted against the DsbA:SSCC ratio. Data were fitted according to equation 3 (solid line) and yielded an equilibrium constant of 9.2 ± 5.2. (Inset) Fast oxidation of DsbA–Trx (0.5 µM) by equimolar amounts of the oxidized SSCC variant, measured by stopped-flow fluorescence. The solid line corresponds to a second-order fit, yielding a rate constant of 3.3 × 105 M–1 s–1. (C) Wild-type DsbB oxidizes two molar equivalents of DsbA–Trx. Oxidized wild-type DsbB (1 µM) was titrated with reduced DsbA–Trx, and the fluorescence at 330 nm (circles) was plotted against the DsbA–Trx:DsbB ratio.

We next titrated the oxidized SSCC variant with reduced DsbA–Trx (Figure 4B). The titration data yielded an equilibrium constant of 9.2 ± 5.2, corresponding to a redox potential of –0.186 ± 0.01 V for the 104–130 disulfide in the SSCC variant. This value was used to calculate the equilibrium constant of 146 for oxidation of the 104–130 disulfide by wild-type DsbA, which well agreed with the fluorescence data in Figure 5A [solid line; correlation coefficient (R) = 0.999] (see also Supplementary table I). Like wild-type DsbA, DsbA–Trx did not react with the 41–44 disulfide in the CCSS variant (data not shown).

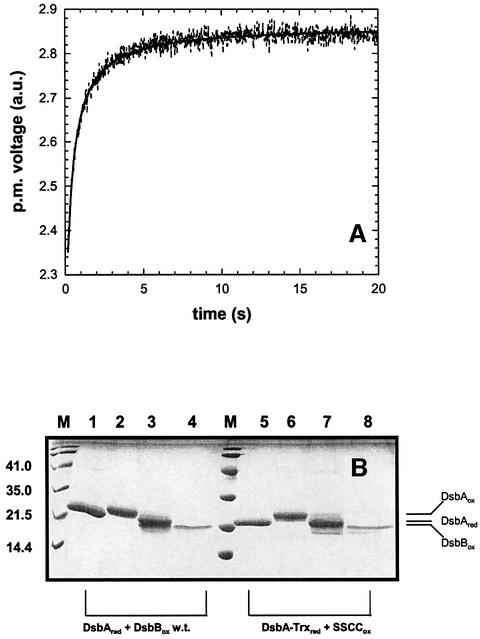

Fig. 5. Rapid oxidation of wild-type DsbA by wild-type DsbB at pH 7.0 in 0.1% (w/v) DM, measured by stopped-flow fluorescence. (A) Oxidized DsbB and reduced DsbA were mixed at a 1:1 ratio (final concentrations: 1 µM each). The increase in fluorescence at 330 nm was recorded and data were fitted according to second-order kinetics (continuous line), yielding a rate constant of 2.7 ± 0.2 × 106 M–1 s–1. (B) Oxidation of DsbA by DsbB does not stop at the level of a DsbB–DsbA mixed disulfide. A Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained, non-reducing SDS gel showns proteins after TCA-precipitation and modification with AMS under the same conditions that were used previously for redox potential determination and identification of intramolecular disulfide bonds between DsbA and DsbB (Inaba and Ito, 2002; Kadokura and Beckwith, 2002; Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002). (Lanes 1–4) Reaction between oxidized DsbB and reduced wild-type DsbA; (lanes 5–8) reaction between the oxidized SSCC variant and reduced DsbA–Trx. Lane 1, oxidized DsbA; lane 2, reduced DsbA; lane 3, 1:1 mixture of reduced DsbA and oxidized wild-type DsbB; lane 4, oxidized wild-type DsbB; lane 5, oxidized DsbA–Trx; lane 6, reduced DsbA–Trx; lane 7, mixture between reduced DsbA–Trx and oxidized SSCC; lane 8, oxidized SSCC. Note that Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining of DsbB is significantly weaker compared with equimolar amounts of DsbA.

The redox potentials of the 41–44 and 104–130 disulfide bonds in DsbB (–0.069 and –0.186 V, respectively) predicted that oxidized DsbB can oxidize two molar equivalents of the reducing DsbA variant DsbA–Trx (–0.214 V) in the absence of ubiquinone, provided that disulfide interchange between the 41–44 and 104–130 disulfides occurs. To test these predictions, we titrated oxidized wild-type DsbB (1 µM) with reduced DsbA–Trx. Figure 4C shows that DsbB indeed oxidizes two molar equivalents of DsbA–Trx. The initial fluorescence change between zero and one molar equivalent of DsbA–Trx added is caused by the 1.5-fold fluorescence increase of DsbB due to reduction of the 41–44 disulfide (after reduction of the 104–130 disulfide and intramolecular disulfide exchange), and by the (weaker) fluorescence decrease due to oxidation of DsbA–Trx. Between one and two molar equivalents of DsbA–Trx, the titration profile is only determined by formation of the second molar equivalent of oxidized DsbA–Trx, as reduction of the 104–130 disulfide in DsbB is spectroscopically silent. The completeness of the reaction is evident from the kink at a DsbB:DsbA–Trx ratio of 2:1, and the signal increase above 2 molar equivalents corresponds to the specific fluorescence of reduced DsbA–Trx.

Oxidation of DsbA by wild-type DsbB is extremely fast, and proceeds without population of a kinetically stable DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfide intermediate

To test the relevance of disulfide exchange between DsbA and DsbB for the catalytic cycle of DsbB, we next measured the kinetics of oxidation of DsbA by wild-type DsbB in the absence of ubiquinone under second-order conditions by stopped-flow fluorescence. Figure 5A shows that the reaction is extremely fast, with a rate constant of 2.7 ± 0.2 × 10 M–1 s–1, corresponding to a reaction half-life of 0.4 s at initial protein concentrations of 1 µM. We then tested the direct oxidation of DsbA by one molar equivalent of ubiquinone Q1 in the presence of equimolar amounts of the cysteine-depleted DsbB variant SSSS. This reaction proved to be ∼103 times slower (estimated k2 ≈ 2 × 10 M–1 s–1, t1/2 ≈ 470 s) (Supplementary figure 3), demonstrating that the catalytically relevant reaction for oxidation of DsbA by DsbB is disulfide exchange. The rate constant of 2.7 ± 0.2 × 10 M–1 s–1 is very similar to the kcat/KM of DsbB (4.5 × 10 M–1 s–1), indicating that disulfide exchange between DsbA and DsbB may nevertheless be rate-limiting in the catalytic cycle of DsbB.

The model for the reaction cycle of DsbB proposed by Kadokura and Beckwith (2002) predicts that the reaction between DsbA and DsbB leads to accumulation of a mixed disulfide species, in which Cys30 of DsbA is disulfide-bonded to Cys104 of DsbB in the absence of ubiquinone. This model is not in agreement with our data on the oxidation of two molar equivalents of DsbA–Trx by wild-type DsbB (Figure 4C), because this reaction requires spontaneous release of the first oxidized DsbA–Trx molecule prior to the reaction of partially reduced DsbB with the second equivalent of DsbA–Trx. To investigate the possibility of a kinetically stable DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfide further, reduced wild-type DsbA was mixed with one molar equivalent of oxidized DsbB in the absence of ubiquinone. The mixture was then treated exactly according to the AMS-modification protocol used by Kadokura and Beckwith (2002) for identification of DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfides. SDS–PAGE analysis of the reaction after AMS modification (Figure 5B) showed that oxidized DsbA is formed quantitatively and released from DsbB, and that a DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfide (43 kDa band) is not populated (Figure 5B, lane 3). We performed an analogous experiment for the reaction between the oxidized DsbB variant SSCC and reduced DsbA–Trx. Again, oxidized DsbA–Trx was quantitatively formed, and no significant population of a mixed disulfide could be detected (Figure 5B, lane 7). We conclude that oxidation of DsbA by fully oxidized DsbB occurs spontaneously under release of oxidized DsbA, and that ubiquinone is required for reoxidation of partially reduced DsbB. We also conclude that inter-loop disulfide exchange in DsbB is extremely fast and not rate-limiting in the reaction cycle of DsbB. The fact that the 41–44 disulfide is ∼104 times more oxidizing than the 104–130 disulfide guarantees a disulfide flip in DsbB to the partially reduced form, in which Cys41 and Cys44 are reduced and accessible for reoxidation by ubiquinone.

Discussion

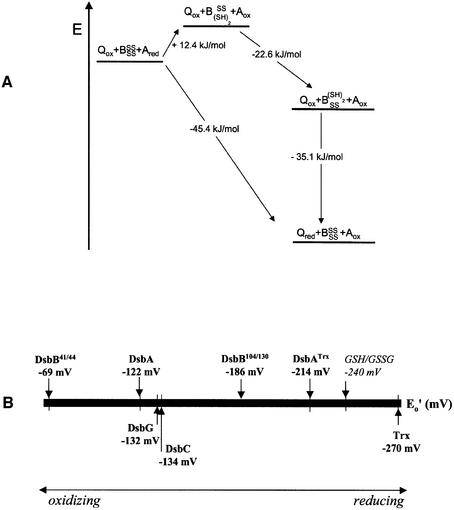

Figure 6A shows the simplest model for the catalytic mechanism of DsbB that we can deduce from our data and data obtained by others (Guilhot et al., 1995; Kishigami and Ito, 1996; Kobayashi and Ito, 1999). The catalytic cycle starts with the oxidation of reduced DsbA by the 104–130 disulfide bond in fully oxidized DsbB. Although this reaction is energetically unfavourable (+12.4 kJ/mol), the energetic cost is more than regained (–22.6 kJ/mol) by subsequent intra-loop disulfide exchange in DsbB to a partially reduced form of DsbB in which the 104–130 disulfide bond is formed and Cys41 and Cys44 are reduced. Simultaneously, this reaction renders the only pair of cysteines in DsbB that can react with ubiquinone (Kobayashi and Ito, 1999; Kobayashi et al., 2001; Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002) accessible to reoxidation by ubiquinone. The latter reaction (which closes the catalytic cycle and regenerates fully oxidized DsbB) is the energetically most favourable step, as ubiquinone is still far more oxidizing (Eo′ = +0.113 V; Gennis and Stewart, 1996) than the 41–44 disulfide (Figure 6A).

Fig. 6. Energy diagram of the proposed catalytic mechanism of DsbB (A). The free enthalpies (ΔG) of the individual reaction steps were calculated from the standard redox potentials according to ΔG = –2·F·ΔE, where F is the Faraday constant and ΔE corresponds to the redox potential difference between the respective species (see Supplementary table I). BSSSS corresponds to fully oxidized DsbB, BSS(SH)2 represents partially reduced DsbB in which the Cys41–44 disulfide bond is formed and Cys104 and Cys130 are reduced, and B(SH)2SS is partially reduced DsbB in which the Cys104–130 disulfide is formed and Cys41 and Cys44 are reduced. A redox potential of +0.113 V was used for ubiquinone/ubiquinol (Gennis and Stewart, 1996). (B) Scale of redox potentials of enzymes involved in disulfide bond formation in E.coli (see Sevier and Kaiser, 2002, and references therein).

Parts of our model for the mechanism of DsbB are in strong contrast to previously published data. The most striking difference is the enormous difference in redox potential of the 41–44 disulfide bond measured by us (–0.069 V) and others. Regeimbal and Bardwell (2002) obtained a value of –0.271 V, and Inaba and Ito (2002) measured values of –0.21 V and –0.28 V without and with added ubiquinone, respectively. Thus, the redox equilibrium constants for the 41–44 disulfide determined by us differ from previous data by up to 7 orders of magnitude. Considering the work of Inaba and Ito (2002), we believe that the redox potential of DsbB in a thiol-disulfide redox buffer cannot be determined accurately in the presence of ubiquinone. This is because DsbB becomes oxidized by ubiquinone, and the newly formed disulfides of DsbB in turn oxidize the thiol compound in the redox buffer, making it impossible to maintain constant redox conditions for equilibrium measurements. Moreover, we would like to stress that our experimental approach differed in several aspects from previous experiments. First, in contrast to the previous studies we exclusively used DsbB preparations completely depleted of ubiquinone Q8. This may explain why we could observe the 1.5-fold increase in tryptophan fluorescence upon reduction the 41–44 disulfide, while Inaba and Ito (2002) reported that DsbB shows no redox-state-dependent fluorescence change. The redox-state-dependent fluorescence of DsbB and DsbA not only allowed us to observe redox equilibria between DsbB and glutathione along with disulfide exchange between DsbA and DsbB, but also established the stoichiometry of the reaction between DsbB and DsbA. Secondly, all previous data on the redox properties of DsbB were obtained indirectly by covalent modification of free thiols by AMS after a TCA precipitation step (Inaba and Ito, 2002; Kadokura and Beckwith, 2002; Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002). We believe that one difficulty with this method is that TCA-precipitated DsbB may become irreversibly denatured, such that accessibility to AMS and reactivity of free thiols may be diminished. Another problem of the method appears to be incomplete protein recovery after TCA precipitation (Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002). Moreover, Cys41 or Cys44 are predicted to be extremely reactive (see below), so that disulfide exchange may occur even under conditions of acid-trapping if DsbB does not become denatured.

According to the model in Figure 6A, the first step in the DsbB reaction cycle, i.e. oxidation of DsbA (Eo′ = –0.122 V) by the 104–130 disulfide of DsbB (Eo′ = –0.186 V), is an energetic uphill reaction (ΔG = +12.4 kJ/mol). This reaction would indeed proceed only to ∼0.7% unless subsequent inter-loop disulfide exchange in DsbB occurred. The disulfide flip in DsbB thus pulls the partially reduced DsbB species with reduced Cys104 and Cys130 from the equilibrium with DsbA, thereby guaranteeing quantitative oxidation of DsbA by DsbB.

The more reducing redox potential of the 104–130 disulfide compared with DsbA has previously been termed ‘paradoxical’ (Inaba and Ito, 2002). We believe that this view is not appropriate to describe the function of DsbB. The reaction catalysed by DsbB is energetically favourable 9–45.4 kJ/mol; equilibrium constant 9 × 107; Figure 6A), but is extremely slow in the absence of DsbB (Regeimbal and Bardwell, 2002). DsbB is thus not a redox substrate, like reduced DsbA or ubiquinone, but an electron transfer catalyst. Almost all reactions catalysed by enzymes, however, pass through one or more intermediates of high energy (Kyte, 1995). The energetically unfavourable DsbB intermediate, in which the 104–130 disulfide is reduced and the 41–44 disulfide is formed, is thus not unexpected. The other intermediates in the DsbB cycle that must be postulated, i.e. the mixed disulfide between Cys30 of DsbA and Cys104 of DsbB, as well as the inter-loop disulfide (possibly 41–130, as suggested by Kadokura and Beckwith, 2002) may be other high-energy intermediates in the DsbB-catalysed reaction.

The fact that DsbA becomes oxidized by DsbB extremely rapidly in the absence of ubiquinone, with an apparent rate constant 2.7 × 106 M–1 s–1 (Figure 5A), while direct oxidation of DsbA by ubiquinone bound to the cysteine-free SSSS variant is 103 times slower is very convincing evidence that oxidation of DsbA occurs by disulfide exchange. The reaction between DsbB and DsbA is about five orders of magnitude faster than disulfide exchange between alkyl thiols (Szajewski and Whitesides, 1980) and thus extremely unlikely to be catalytically irrelevant. Nevertheless, the direct oxidation of DsbA by DsbB may be the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle of DsbB, as its rate constant practically equals the kcat/KM of DsbB.

In addition, we can clearly eliminate the possibility that the reaction between oxidized DsbB and reduced DsbA stops at a mixed-disulfide intermediate in which Cys30 of DsbA is disulfide-bonded to Cys104 of DsbB, and Cys41 and Cys130 of DsbB simultaneously form an inter-loop disulfide as proposed previously by Kadokura and Beckwith (2002), for the following reasons. First, DsbB oxidizes two molar equivalents of the DsbA–Trx variant (Figure 4C). As only the 104–130 disulfide of DsbB interacts with DsbA, the second molar equivalent of DsbA–Trx can be oxidized only when the first DsbA–Trx molecule is released by DsbB. Secondly, we could not detect DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfides by covalent modification of free thiols when oxidized DsbB and reduced DsbA were mixed in the absence of ubiquinone in vitro (Figure 5B). Stable mixed disulfides could also not be detected when the oxidized SSCC variant of DsbB was mixed with the reduced DsbA–Trx variant (Figure 5B). As oxidation of DsbA by DsbB occurs via disulfide exchange, DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfides must occur as reaction intermediates. However, mixed disulfides are generally very unstable and short-lived, as they can be dissolved rapidly by subsequent formation of entropically more favourable intra-molecular disulfides. In principle, DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfides may be stabilized by additional specific interactions between non-cysteine side chains and complementary surfaces in DsbA and DsbB, but DsbB has been shown to be rather promiscuous with respect to its dithiol oxidase substrate, as it also accepts cytoplasmic thioredoxin (Jonda et al., 1999; Debarbieux and Beckwith, 2000) and eukaryotic protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (Ostermeier et al., 1996). The DsbB–DsbA interaction thus appears to depend mainly on the accessibilities and intrinsic reactivities of the involved cysteine residues, rather than on surface complementarity.

From the present data, we cannot make any statements on the cysteines that are involved in formation of the inter-loop disulfide that is formed in the catalytic cycle of DsbB. Kadokura and Beckwith (2002) detected an inter-loop disulfide between Cys41 and Cys130, and simultaneous formation of a mixed disulfide between Cys30 of DsbA and Cys104 of DsbB. This is in contrast to the results of Kobayashi and Ito (1999) who proposed that Cys104 may react with DsbA and may also form the inter-loop disulfide. Our data are compatible with both models, as immediate release of oxidized DsbA through attack of the thiol of Cys33 in DsbA on the DsbA/Cys30-DsbB/Cys104 mixed disulfide generates the partially reduced form of DsbB in which both Cys104 and Cys130 are reduced, so that either of the two cysteines may attack the 41–44 disulfide bond. In addition, all thiols in native DsbB are solvent-exposed and can be modified by IAM (Table I). An attractive feature of the model of Kadokura and Beckwith with simultaneous formation of the DsbA–DsbB mixed disulfide and the 41–130 inter-loop disulfide is that Cys130 of DsbB can no longer attack the mixed disulfide between DsbA and DsbB, thus preventing back-reaction to reduced DsbA. Determination of the redox potential of the inter-loop disulfide (e.g. 41–130 in a CSSC variant of DsbB) would allow calculation of its fraction in partially reduced DsbB. Our equilibrium experiments with glutathione revealed that wild-type DsbB is slightly more oxidizing than the CCSS variant (Keq = 1.7 × 10–6 M compared with 1.3 × 10–5 M, respectively; Figure 2). If this was due to formation of an inter-loop 41–130 disulfide in wild-type DsbB that is more oxidizing (i.e. unstable) than the 41–44 disulfide, the 41–130 disulfide would not be significantly populated in partially reduced DsbB. In any case, oxidation of DsbA by DsbB can also occur without formation of the 41–104 disulfide, as the SSCC variant of DsbB, which lacks Cys41 and Cys44, efficiently oxidizes and releases the DsbA–Trx variant (Figures 4B and 5B). Equivalent evidence comes from the fact that wild-type DsbB oxidizes two molar equivalents of DsbA–Trx (Figure 4C). We therefore assume that the first redox transition in wild-type DsbB (Figure 2) indeed corresponds to the reduction of the 41–44 disulfide, and that the slightly more reducing properties of Cys41/Cys44 in the CCSS variant are due to minor local changes in the DsbB structure. It must mentioned, however, that the disulfide bond pattern 41–44 and 104–130 in fully oxidized wild-type DsbB has not been established at the protein level and has only been deduced from disulfide bond formation in the CCSS and SSCC variants. Thus, it could principally be that oxidized DsbB contains two inter-loop disulfide bonds. We consider this possibility very unlikely because alternative disulfide bond patterns are normally not observed in a folded protein. In addition, Kadokura and Beckwith (2002) observed formation of the 41–44 and 104–130 disulfide and no inter-molecular disulfide bonds when the DsbB segments 1–90 and 86–176 were coexpressed and formed a biologically active heterodimer.

It is tempting to speculate on the molecular reasons underlying the extreme intrinsic oxidative force of the 41–44 disulfide in DsbB, for which theory predicts that one of the active-site cysteines (possibly Cys41) has a pKa <3 (Nelson and Creighton, 1994; Mössner et al., 2000). The 41–44 disulfide of DsbB is rather close to the N-terminus of the second predicted transmembrane α-helix of DsbB (starting at residue 49). As the reactive thiolate groups of enzymes from the thioredoxin family are located at the N-terminus of an α-helix (see Guddat et al., 1998 and references therein), it is conceivable that the second transmembrane α-helix of DsbB extends to the layer of lipid head groups and already starts at Cys41. The conserved Arg48, which has been shown to interact with ubiquinone (Kadokura et al., 2000), may additionally contribute to a lowered pKa of Cys41 or Cys44.

Materials and methods

Construction of expression plasmids for wild-type DsbB and DsbB variants

A 537-bp fragment, encoding DsbB with a C-terminal His6-tag, was amplified using PCR from genomic DNA of E.coli W3110 with the primers 5′-CCCCCCGCATATGCTGCGATTTTTAAACCAATGTTT GACAAG-3′ and 5′-GGCGGATCCTTAGTGATGATGGTGATGGTG GCCACGACCGAACAGATCGCGTTTTTTCG-3′, and cloned into pDsbA3 (Hennecke et al., 1999) via NdeI and BamHI. The codons for the two non-essential cysteine residues Cys8 and Cys49 (Jander et al., 1994; Bader et al., 1999) were then replaced by serine and valine codons, respectively (QuickChange, Stratagene), yielding pDsbB. The variants CCSS, SSCC and SSSS were constructed from pDsbB using the QuickChange method. The genes encoding wild-type DsbB and its variants were verified by dideoxy sequencing.

Expression and purification of ubiquinone-free wild-type DsbB and DsbB variants

For expression of DsbB, E.coli HM125 (Meerman and Georgiou, 1994) harbouring pDsbB was grown in 1 l of LB-amp medium at 30°C. At an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6–0.8, IPTG was added (10 µM). Cells were grown further for 4 h and harvested. Cell membranes were prepared exactly as described previously (Bader et al., 1998), suspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.5, and stored after freezing in liquid nitrogen at –80°C. Membrane proteins were solubilized in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 1 M NaCl, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 pH 8.0, by four strokes with a Dounce homogenisator and incubation on ice for 1 h. After removal of insoluble material by centrifugation (100 000 g), the supernatant was applied to a Ni-NTA Superflow column (Qiagen) equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed extensively with 50 mM sodium phosphate, 1 M NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DM) (pH 8.0), then with one column volume of 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 1% (w/v) lauroylsarcosine (pH 8.0) and then with 5 column volumes of 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 6.2. Recombinant DsbB was eluted with a linear gradient from 0 to 500 mM imidazole/HCl in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 6.2. Fractions containing DsbB were pooled and applied to a hydroxyapatite column (Bio-Rad) equilibrated with 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 6.2. Proteins were eluted along a linear gradient from 50 mM to 500 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.2 in 0.1% (w/v) DM. Fractions containing DsbB were pooled and dialysed against 100 mM sodium phosphate, 0.1 mM EDTA pH 7.0. The yield of purified DsbB was 4 mg per litre of bacterial culture, and the protein was fully oxidized as shown by Ellman’s assay (Riddles et al., 1983). The DsbB variants CCSS, SSCC and SSSS were purified according to the same protocol. The absence of ubiquinone Q8 in the protein preparations was verified by recording ultra-violet (UV) spectra before and after treatment with NaBH4 (Bader et al., 2000). Wild-type DsbA (Hennecke et al., 1999) and the DsbA–Trx variant (Huber-Wunderlich and Glockshuber, 1998) were purified as described.

Determination of protein concentrations

Protein concentrations were determined using their extinction coefficients at 280 nm according to Gill and von Hippel (1989) with the following ε280 nm values: 23 250 M–1cm–1 (wild-type DsbA and DsbA–Trx), 47 750 M–1cm–1 (oxidized wild-type DsbB), 47 630 M–1cm–1 (oxidized SSCC and oxidized CCSS) and 47 510 M–1cm–1 (reduced wild-type DsbB, reduced SSCC, reduced CCSS, and SSSS). An extinction coefficient at 275 nm of 13 700/M/cm was used for ubiquinone Q1.

Fluorescence spectroscopy and determination of redox potentials

Fluorescence experiments were performed on a Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrometer at 25°C in 100 mM sodium phosphate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 7.0, using an excitation wavelength of 280 nm. DsbB concentrations were 1–2 µM in all experiments. For recording of fluorescence spectra of the completely reduced proteins, DTT (final concentration of 200 µM) was included. Titration experiments were performed in stirred 1 × 0.5 cm quartz cuvettes (right-angle arrangement). Band widths were 5 nm for the excitation beam and 10 nm for the emission beam.

For determination of equilibrium constants between DsbB or DsbA and glutathione, the redox state of the protein at different [GSH]2:[GSSG] ratios was followed by the change in fluorescence at 330 nm. Oxidized proteins (2 µM) were incubated for 16 h in 1 mM GSSG and different concentrations of GSH (0.2 µM to 11 mM). To exclude air oxidation, all buffers were degassed and flushed with argon. Equilibrium constants (Keq) were calculated according to equation 1:

F = Fox + (Fred – Fox)([GSH]2/[GSSG])/(Keq + [GSH]2/[GSSG])

where F is the fluorescence signal at 330 nm, and Fox and Fred are the fluorescence intensities of completely oxidized and reduced protein, respectively. Non-linear regression analysis (Kaleidagraph, Synergy Software) yielded correlation coefficients ≥0.994 for all redox transitions. Standard redox potentials were calculated using the Nernst equation:

Eo′protein = Eo′GSH/GSSG – (RT/2F) ln Keq

using a value of –0.240 V for the redox potential of glutathione (Eo′GSH/GSSG).

The redox potential of the SSCC variant was determined by titration of oxidized SSCC with the reduced DsbA variant DsbA–Trx (Eo′ = –0.214 V). Reduced DsbA–Trx was prepared by reduction with DTT, followed by gel filtration on a NAP 5 column (Amersham-Pharmacia). Oxidized SSCC (1 µM) in a 1 ml volume was titrated by stepwise addition of reduced DsbA–Trx (28.5 µM). The fluorescence was recorded at 330 nm and corrected for the volume increase. Data were fitted according to equation 3:

F = fAx + fB + (fC – fA) × (2Keq – 2)–1 ×

((Keqx + Keq) – ((Keqx + Keq)2 – 4Keq2x – 4Keqx)1/2)

where F is the measured fluorescence at 330 nm, fA and fC are the specific signals at 330 nm of reduced and oxidized DsbA–Trx, respectively, fB is the specific fluorescence of SSCC, x represents the molar equivalents of reduced DsbA–Trx added, and Keq is the equilibrium constant. An analogous titration was performed with the reduced SSCC variant and oxidized wild-type DsbA. Data were again fitted according to equation 3, except that fA here corresponds to the specific fluorescence of oxidized DsbA, and fC to the specific fluorescence of reduced DsbA at 330 nm.

Stoichiometries of reactions between DsbA and DsbB were established as follows. Oxidized wild-type DsbB (1 µM) in a volume of 1 ml was titrated stepwise with 2 µl aliquots of a solution of reduced DsbA (100 µM) or with 5 µl steps of a solution of reduced DsbA–Trx (29.8 µM). The fluorescence at 330 nm was recorded after 1 min of incubation and corrected for the volume increase. Data from the titration of DsbB with DsbA were fitted according to equation 4:

F = fAx + fB + (fC + fD – fA – fB) × (2Keq – 2)–1 ×

((Keqx + Keq) – ((Keqx + Keq)2 – 4Keq2x – 4Keqx)1/2)

where fA and fC are the signals of reduced and oxidized DsbA, and fB and fD are the signals of oxidized and reduced wild-type DsbB, respectively. To determine the amount of ubiquinone Q1 required to oxidize DsbA in the presence of catalytic amounts of wild-type DsbB, a mixture of reduced DsbA (1 µM) and oxidized DsbB (27 nM) (1 ml) was titrated in 2 µl steps with a solution of ubiquinone Q1. After incubation for 5 min, the fluorescence at 330 nm was recorded and corrected for the volume increase.

Mass spectrometry and protein modification

For recording MALDI-TOF mass spectra, 1 µl of protein solution (1–15 µM) was mixed with 9 µl of saturated sinapinic acid in 66% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.1% (v/v) TFA. A 1.5 µl aliquot was dried on the MALDI-target, and mass spectra were recorded on a Voyager Elite MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Perspective Biosystems). The spectrometer was calibrated with a mixture of horse insuline, E.coli thioredoxin, human myoglobin and E.coli DsbA.

For modification of free thiols in DsbB, IAM or NEM was added to a final concentration of 5 mM in 100 mM sodium phosphate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 7.0, followed by incubation at 25°C in the dark (20 min). AMS modification was performed at protein concentrations of 1 µM and stopped after 10 min by the addition of TCA as described previously (Kobayashi and Ito, 1999).

Stopped-flow fluorescence experiments

The kinetics of the oxidation of DsbA (1 µM) by wild-type DsbB (1 µM), and of the oxidation of DsbA–Trx (0.5 µM) by the SSCC variant (0.5 µM) (final protein concentrations) in 100 mM sodium phosphate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (w/v) DM pH 7.0, were monitored at 25°C by the change in fluorescence at 330 nm using stopped-flow mixing in an Applied Photophysics SX-17MV instrument (1:1 mixing ratio). Data from eight independent reactions were averaged and evaluated according to second-order kinetics.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Vetsch for many stimulating and helpful discussions, Professor Eilika Weber-Ban for help during stopped-flow fluorescence measurements, and Drs René Brunisholz and Thomas Denzinger (Protein Service Laboratory, ETH Zurich) for assistance in mass spectrometry. This project was supported by the Schweizerische Nationalfonds and the ETH Zurich within the framework of the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) program in Structural Biology.

References

- Bader M., Muse,W., Zander,T. and Bardwell,J. (1998) Reconstitution of a protein disulfide catalytic system. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 10302–10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader M., Muse,W., Ballou,D.P., Gassner,C. and Bardwell,J.C. (1999) Oxidative protein folding is driven by the electron transport system. Cell, 98, 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader M.W., Xie,T., Yu,C.A. and Bardwell,J.C. (2000) Disulfide bonds are generated by quinone reduction. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 26082–26088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell J.C., McGovern,K. and Beckwith,J. (1991) Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell, 67, 581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell J.C., Lee,J.O., Jander,G., Martin,N., Belin,D. and Beckwith,J. (1993) A pathway for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 1038–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet J.F. and Bardwell,J.C. (2002) Oxidative protein folding in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol., 44, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey F.E. and Berg,H.C. (1993) Mutants in disulfide bond formation that disrupt flagellar assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 1043–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby N.J. and Creighton,T.E. (1995) Catalytic mechanism of DsbA and its comparison with that of protein disulfide isomerase. Biochemistry, 34, 3576–3587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarbieux L. and Beckwith,J. (2000) On the functional interchangeability, oxidant versus reductant, of members of the thioredoxin superfamily. J. Bacteriol., 182, 723–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennis R.B. and Stewart,V. (1996) Escherichia coli and Salmonella—Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Gill S.C. and von Hippel,P.H. (1989) Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem., 182, 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guddat L.W., Bardwell,J.C. and Martin,J.L. (1998) Crystal structures of reduced and oxidized DsbA: investigation of domain motion and thiolate stabilization. Structure, 6, 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilhot C., Jander,G., Martin,N.L. and Beckwith,J. (1995) Evidence that the pathway of disulfide bond formation in Escherichia coli involves interactions between the cysteines of DsbB and DsbA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 9895–9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennecke J., Sebbel,P. and Glockshuber,R. (1999) Random circular permutation of DsbA reveals segments that are essential for protein folding and stability. J. Mol. Biol., 286, 1197–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber-Wunderlich M. and Glockshuber,R. (1998) A single dipeptide sequence modulates the redox properties of a whole enzyme family. Fold. Des., 3, 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K. and Ito,K. (2002) Paradoxical redox properties of DsbB and DsbA in the protein disulfide-introducing reaction cascade. EMBO J., 21, 2646–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander G., Martin,N.L. and Beckwith,J. (1994) Two cysteines in each periplasmic domain of the membrane protein DsbB are required for its function in protein disulfide bond formation. EMBO J., 13, 5121–5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonda S., Huber-Wunderlich,M., Glockshuber,R. and Mössner,E. (1999) Complementation of DsbA deficiency with secreted thioredoxin variants reveals the crucial role of an efficient dithiol oxidant for catalyzed protein folding in the bacterial periplasm. EMBO J., 18, 3271–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadokura H. and Beckwith,J. (2002) Four cysteines of the membrane protein DsbB act in concert to oxidize its substrate DsbA. EMBO J., 21, 2354–2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadokura H., Bader,M., Tian,H., Bardwell,J.C. and Beckwith,J. (2000) Roles of a conserved arginine residue of DsbB in linking protein disulfide-bond-formation pathway to the respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 10884–10889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadokura H., Katzen,F. and Beckwith,J. (2003) Protein disulfide bond formation in procaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 72, 111–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishigami S. and Ito,K. (1996) Roles of cysteine residues of DsbB in its activity to reoxidize DsbA, the protein disulphide bond catalyst of Escherichia coli. Genes Cells, 1, 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishigami S., Kanaya,E., Kikuchi,M. and Ito,K. (1995) DsbA–DsbB interaction through their active site cysteines. Evidence from an odd cysteine mutant of DsbA. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 17072–17074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. and Ito,K. (1999) Respiratory chain strongly oxidizes the CXXC motif of DsbB in the Escherichia coli disulfide bond formation pathway. EMBO J., 18, 1192–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Kishigami,S., Sone,M., Inokuchi,H., Mogi,T. and Ito,K. (1997) Respiratory chain is required to maintain oxidized states of the DsbA–DsbB disulfide bond formation system in aerobically growing Escherichia coli cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 11857–11862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Takahashi,Y. and Ito,K. (2001) Identification of a segment of DsbB essential for its respiration-coupled oxidation. Mol. Microbiol., 39, 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J. (1995) Mechanism in Protein Chemistry. Garland Publishing, Inc., New York, NY, p. 373. [Google Scholar]

- Meerman H.J. and Georgiou,G. (1994) Construction and characterization of a set of E.coli strains deficient in all known loci affecting the proteolytic stability of secreted recombinant proteins. Biotechnology, 12, 1107–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Georgopoulos,C. and Raina,S. (1993) Identification and characterization of the Escherichia coli gene dsbB, whose product is involved in the formation of disulfide bonds in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 7084–7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mössner E., Iwai,H. and Glockshuber,R. (2000) Influence of the pK(a) value of the buried, active-site cysteine on the redox properties of thioredoxin-like oxidoreductases. FEBS Lett., 477, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J.W. and Creighton,T.E. (1994) Reactivity and ionization of the active site cysteine residues of DsbA, a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Biochemistry, 33, 5974–5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermeier M., De Sutter,K. and Georgiou,G. (1996) Eukaryotic protein disulfide isomerase complements Escherichia coli dsbA mutants and increases the yield of a heterologous secreted protein with disulfide bonds. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 10616–10622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regeimbal J. and Bardwell,J.C. (2002) DsbB catalyzes disulfide bond formation de novo. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 32706–32713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddles P.W., Blakeley,R.L. and Zerner,B. (1983) Reassessment of Ellman’s reagent. Methods Enzymol., 91, 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevier C.S. and Kaiser,C.A. (2002) Formation and transfer of disulphide bonds in living cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 3, 836–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szajewski R.P. and Whitesides,G.M. (1980) Rate constants and equilibrium constants for thiol-disulfide interchange reactions involving oxidized glutathione. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 102, 2011–2026. [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich M. and Glockshuber,R. (1993) Redox properties of protein disulfide isomerase (DsbA) from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci., 2, 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich M., Otto,A., Seckler,R. and Glockshuber,R. (1993) Bacterial protein disulfide isomerase: efficient catalysis of oxidative protein folding at acidic pH. Biochemistry, 32, 12251–12256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun A. and Creighton,T.E. (1994) Effects of DsbA on the disulfide folding of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor and alpha-lactalbumin. Biochemistry, 33, 5202–5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun A., Bardwell,J.C. and Creighton,T.E. (1993) The reactive and destabilizing disulfide bond of DsbA, a protein required for protein disulfide bond formation in vivo. Biochemistry, 32, 5083–5092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]