Abstract

Glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase is a biotin-dependent ion pump whereby the free energy of the glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylation to crotonyl-CoA drives the electrogenic transport of sodium ions from the cytoplasm into the periplasm. Here we present the crystal structure of the decarboxylase subunit (Gcdα) from Acidaminococcus fermentans and its complex with glutaconyl-CoA. The active sites of the dimeric Gcdα lie at the two interfaces between the mono mers, whereas the N-terminal domain provides the glutaconyl-CoA-binding site and the C-terminal domain binds the biotinyllysine moiety. The Gcdα catalyses the transfer of carbon dioxide from glutaconyl-CoA to a biotin carrier (Gcdγ) that subsequently is decarboxylated by the carboxybiotin decarboxylation site within the actual Na+ pump (Gcdβ). The analysis of the active site lead to a novel mechanism for the biotin-dependent carboxy transfer whereby biotin acts as general acid. Furthermore, we propose a holoenzyme assembly in which the water-filled central channel of the Gcdα dimer lies co-axial with the ion channel (Gcdβ). The central channel is blocked by arginines against passage of sodium ions which might enter the central channel through two side channels.

Keywords: biotin/carboxyltransferase/glutaconyl-CoA/ion pump/structure

Introduction

Several strictly anaerobic bacteria from the phyla Firmicutes (order Clostridiales) and Fusobacteria conserve energy gained by the fermentation of amino acids to ammonia, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, acetate and short chain fatty acids (Buckel, 2001a). In these pathways, ATP is usually synthesized via substrate level phosphorylation from acetylphosphate. Furthermore, some glutamate- fermenting organisms are able to conserve the free energy released from decarboxylation of glutaconyl-CoA to crotonyl-CoA (ΔG°′ = –30 kJ/mol) by the generation of an electrochemical sodium ion gradient (Buckel, 2001b; Buckel and Semmler, 1982, 1983) that may be utilized for hydrogen formation from NADH (Härtel and Buckel, 1996).

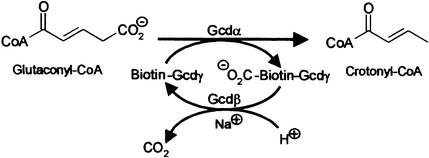

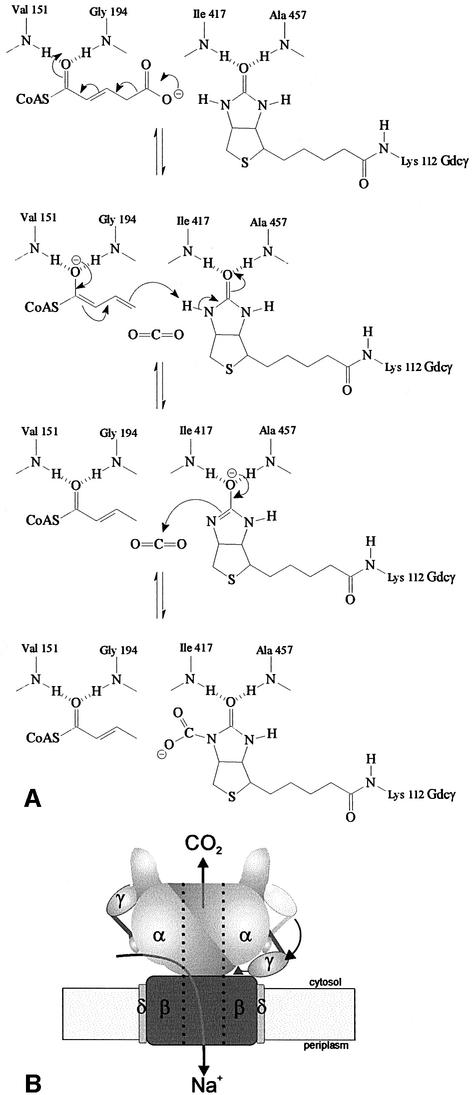

The fermentation of glutamate starts with the oxidative deamination of the amino acid, and leads, via several intermediates, to glutaconyl-CoA. This is decarboxylated to crotonyl-CoA, which disproportionates to acetate, hydrogen and butyrate (Buckel, 1980; Buckel and Barker, 1974). The decarboxylation reaction is catalysed by integral membrane enzymes, which have been isolated from several anaerobic bacteria: Acidaminococcus fermentans, Clostridium symbiosum, Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus and Fusobacterium nucleatum. All four decarboxylases are composed of four different subunits and contain biotin as prosthetic group. The α-subunit (Gcdα, 64.3 kDa) of the A.fermentans enzyme has been identified as carboxyltransferase, which mediates the transfer of carbon dioxide from glutaconyl-CoA to the highly mobile biotin that is covalently attached to the γ-subunit (Gcdγ, 14.1 kDa) (Buckel and Liedtke, 1986; Bendrat et al., 1990). The resultant N1-carboxybiotin (Berger et al., 1996) is decarboxylated by the β-subunit (Gcdβ, 38.9 kDa), the sodium ion pump with 11 putative transmembrane helices, and carbon dioxide is released into the cytoplasm (Dimroth and Thomer, 1983; Hilpert and Dimroth, 1983) (Figure 1). The Gcdδ subunit (11.6 kDa) contains one putative transmembrane helix and probably acts as anchor for the α-subunit to the membrane (Braune et al., 1999). In addition to the glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase, two other Na+-translocating biotin-containing decarboxylases are described: methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase from Veillonella parvula and Propionigenium modestum as well as the oxaloacetate decarboxylase from Klebsiella pneumoniae (Dimroth, 1990). The highest protein sequence similarity exists between the biotin carriers and the carboxybiotin-decarboxylating ion pumps of the proteins. In contrast, the protein sequences of the different transcarboxylating subunits show only very few similarities. The Gcdα subunit of the glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase from A.fermentans, described in this report, shares the highest sequence similarity with the cabrboxyltransferase subunits of propionyl-CoA carboxylase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Buckel, 2001b). The Na+ translocation across the membrane by the ion pump has been studied most intensively with the oxaloacetate decarboxylase from K.pneumoniae (Dimroth et al., 2001). It could be shown that the proton required for the decarboxlation of N1-carboxybiotin originates from the periplasm, whereas up to two Na+ are transported in the opposite direction (Di Berardino and Dimroth, 1996).

Fig. 1. Decarboxylation of glutaconyl-CoA to crotonyl-CoA catalysed by the Gcdα and the Gcdβ subunit of glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase. The biotin carrier Gcdγ serves as a flexible linker between the active sites of the two enzymes.

The arrangement of the subunits within the glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase as well as the transfer of the carboxylated biotin between the Gcdα and Gcdβ subunits are still unknown. To gain some insights into these enigmas and to learn, furthermore, about the mechanism of the consecutive C–C bond breakage and N–C bond formation, we attempted to crystallize the Gcdα subunit and the Gcd holoenzyme. In this report, we present the crystal structure of the glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase Gcdα subunit at 2.2 Å resolution as the first three-dimensional structure of a biotin-dependent carboxyltransferase.

Results and discussion

The overall structure

The recombinant glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase α-subunit (Gcdα) from A.fermentans was crystallized in space group P41212. The X-ray structure of the protein was solved by multiwavelenght anomalous dispersion (MAD) phasing using four platinum sites and was refined at 2.2 Å resolution to a final R-factor of 20.1% (Rfree 22.7%). The asymmetric unit contains a Gcdα dimer of structurally identical monomers.

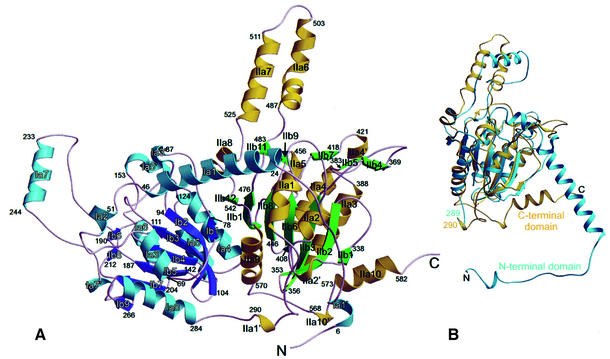

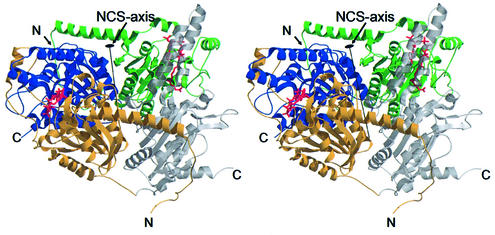

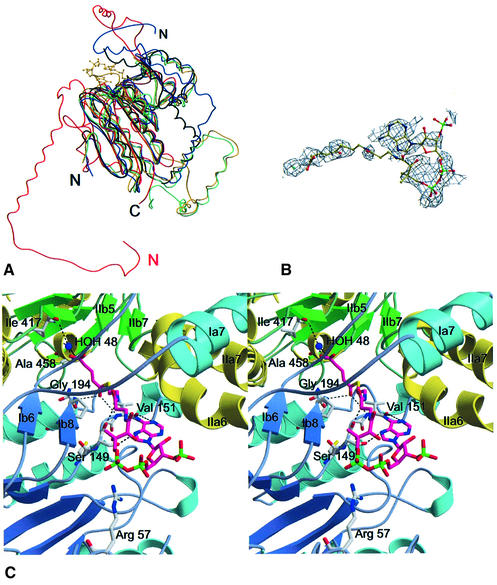

The dimeric state in the crystal corresponds to the results of analytical gel filtration experiments in which the Gcdα protein revealed an apparent molecular mass of 158 kDa, a value that corresponds approximately to the theoretical molecular mass of a dimer (129.2 kDa). During the refinement, it became obvious that the Gcdα monomer (Figure 2A) is organized in two structurally and sequentially similar domains, an N-terminal domain of 289 residues and a C-terminal domain of 297 residues. The domains superimpose with an r.m.s.d. of 1.52 Å of 125 matched contiguous Cα atoms (Figure 2B) and show 15.2% identity and 29.1% similarity between amino acids in structurally equivalent positions. Both domains contain a seven-stranded mostly parallel β-sheet that is sandwiched between layers of three and four α-helices on both sides (Figure 2A). The characteristic α–β motif repeats three times and forms an open α/β-fold that can be assigned to the Clp/crotonase-like fold. Contacts between the two domains are formed by the helix Ia4 that is packed against the β-sheet of the C-terminal domain and helix IIa9 that is packed against the β-sheet of the N-terminal domain. In the latter domain, a small β-sheet with two parallel strands (Ib6 and Ib8) is packed on top of the large sheet. The C-terminal domain contains two small β-sheets, one with two parallel strands (IIb9 and IIb11) and one with three antiparallel β-strands (IIb4, IIb5 and IIb7), at this position. The extended N-terminus of the protein wraps the C-terminal domain with the helices Ia1′ and Ia1. The most striking motif in the C-terminal domain is the bundle of two antiparallel α-helices, IIa6 and IIa7, that protrudes from the protein core, and will be referred to as the ‘helix finger’. A similar ‘helix finger’ exists in the N-terminal domain, but with the shorter helix Ia7. The two monomers interact in such a way that the N-terminal domain of each monomer forms exclusive contacts with the C-terminal domain of the adjacent monomer. The ‘helix fingers’ of the domains pack against each other and form a cavity beneath (Figure 3).

Fig. 2. Overall structural model of the Gcdα monomer. (A) The N-terminal domain is represented in violet (α-helices Ia1′–Ia8) and blue (β-strands Ib1–Ib9). The C-terminal domain is coloured green (β-strands IIb1–IIb12) and yellow (α-helices IIa1′–IIa10). The numbering of the protein sequence is indicated. (B) The structural superposition of the two Gcdα domains (turquoise, N-terminal domain; yellow, C-terminal domain) visualizes their structural similarity.

Fig. 3. Stereo representation of the Gcdα dimer with differently coloured domains. The N-terminal domain of monomer A is shown in yellow, the C-terminal domain is displayed semitransparently in grey, the N-terminal domain of monomer B is shown in green and the C-terminal domain in blue. The glutaconyl-CoA molecules in the two substrate-binding pockets of the dimer are drawn as stick models.

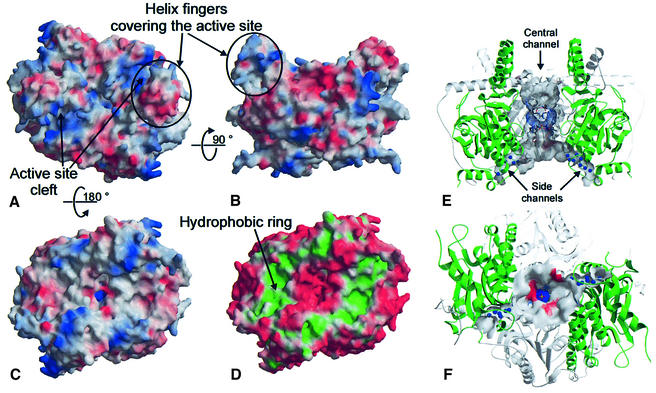

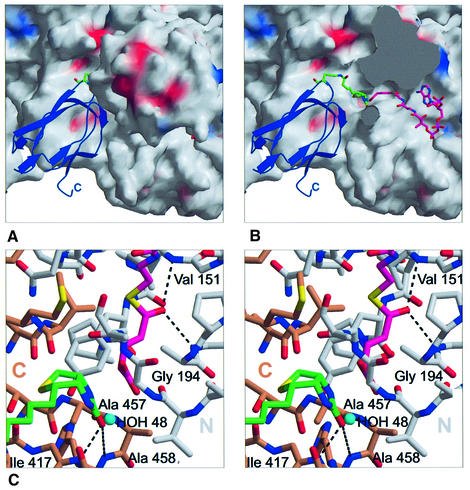

This spatial arrangement of the domains results in a wide water-filled channel (Figure 4A, B, E and F) co-axial with the non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) axis. In the crystal structure, this central channel is nearly blocked by the side chains of Arg164A and Arg164B that coordinate a sulfate ion originating from the crystallization buffer (Figure 4E). These residues, together with the side chains of Arg172A and Arg172B, form a positive surface patch at the narrowest part of the channel (Figure 4C and E), whereas other parts of the channel are covered with negative charges (Figure 4E). In addition to the main channel, two small hydophilic channels lead from the lower part of the central channel sideways through the dimer (Figure 4E and F). Within these small channels electron density is located that could be assigned to water or monovalent ions. Some of these sites are coordinated by carbonyl oxygens that line the side channels, but no position with a complete octahedral coordination sphere is found, and consequently the density was interpreted as water molecules.

Fig. 4. Outer and inner surface of the Gcdα dimer. The electrostatic surface potential from negative (red) to positive (blue) is mapped onto different orientations of the solid surface representation of the Gcdα dimer. (A) View onto the surface region that contains both active site pockets. (B) Side view of the molecule. The ‘helix fingers’ are marked in (A) and (B). (C) The surface in (A) was rotated by 180° and the contact region that is proposed to serve as an interaction site with the ion pump Gcdβ becomes visible. (D) When the contribution of hydrophobic (green) and hydrophilic (red) residues is mapped onto the surface, a hydrophobic ring in the contact region becomes visible. (E) The Gcdα dimer contains several water-filled channels that are displayed using the semitransparent inner surface of the dimer in the same orientation as in (B). The water molecules within the side channels are displayed as blue balls. To simplify the figure, the N-terminal domains are in grey and transparent, and the two C-terminal domains are in green. (F) View onto the opening of the channels towards the contact region. Within the crystal structure, the central channel is blocked by a sulfate ion that is displayed as a stick model.

Structurally homologous proteins

Searches using a polyalanine model of the Gcdα monomer with the program DALI (Holm and Sander, 1993) against the RSCB protein databank (Berman et al., 2000) yielded several protein structures of the crotonase superfamily. Four structurally similar proteins could be identified that display an overall r.m.s.d. of 3 Å for matching Cα atoms with the Gcdα structure: (i) 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA dehalogenase from Pseudomonas sp. (pdb code 1NYZ), an enzyme that hydrolyses 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA to 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA in the chlorobenzoate degradation pathway (Benning et al., 1996); (ii) Δ3,5-Δ2,4-dienoyl-CoA isomerase from Rattus norwegicus (pdb code 1DCI), that catalyses the isomerization of 2-trans-4-trans-dienoyl-CoA in the degradation pathway of unsaturated fatty acids (Modis et al., 1998); (iii) methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase from Escherichia coli (pdb code 1EF8) (Benning et al., 2000); and (iv) Δ2-Δ3-enoyl-CoA isomerase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (pdb code 1HNO), an enzyme that is also involved in the degradation of unsaturated fatty acids and transforms 3-cis-enoyl-CoA and 3-trans-enoyl-CoA to 2-trans-enoyl-CoA (Mursula et al., 2000).

In contrast to the homodimeric Gcdα, the mentioned structurally related proteins are homohexamers, with the exception of the trimeric 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA dehalogenase. Nevertheless, each monomer of these proteins is approximately the same size as one Gcdα domain and superimposes equally well with both domains of Gcdα. Therefore, the glutaconyl-CoA-binding site could be allocated to both domains.

Figure 5A shows the superposition of the structurally related proteins with the N-terminal domain of Gcdα. Despite the obvious structural similarity between the homologues, no significant sequence similarity exists. All structural homologues bind different CoA-thioester substrates in substrate-binding pockets that are located, with the exception of the methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase, at the interface of two monomers.

Fig. 5. The active site of Gcdα. (A) Superposition of the Gcdα N-terminal domain (red) and the structurally related proteins 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA dehalogenase (yellow), dienoyl-CoA isomerase (green), methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase (blue) and enoyl-CoA isomerase (black). The ligand of the 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA dehalogenase structure 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA is displayed as a yellow stick-model. (B) Representative electron density corresponding to the bound glutaconyl-CoA. The 2Fo – Fc map was calculated to 3.2 Å resolution and contoured to 0.5σ. The glutaconyl-CoA and the water in the active site of the complex are displayed in ball-and-stick. (C) Stereo representation of the active site. The glutaconyl-CoA (magenta) and the prominent water molecule (see text) are shown in ball-and-stick representation. Hydrogen bonds that stabilize the substrate and the water within the pocket are displayed, and the residues involved are labelled.

The substrate-binding site

The binding site of glutaconyl-CoA cannot be deduced from a comparison with structurally related proteins because the N- and C-terminal domains of Gcdα superimpose equally well with the homologues. Therefore, we attempted to solve the structure of Gcdα substrate complexes, which was complicated by the short lifetime of the crystals and their fatal reaction upon soaks with biotin and its derivatives. Nevertheless, freshly grown native crystals could be soaked with the hydrolysis-sensitive substrate glutaconyl-CoA and the structure of the Gcdα–glutaconyl-CoA complex was solved at a resolution of 3.2 Å by Patterson search techniques using the the apoenzyme as search model. The structure of the complex was refined to a final R-factor of 18.8% (Rfree 24.2%). Additional electron density appeared in the proposed glutaconyl-CoA-binding site of the N-terminal domain that could be assigned to this substrate (Figure 5B). Due to the low resolution of the data set, the electron density of the substrate is weak, but allowed the positioning of the adenine ring and the glutaconyl moiety of the substrate in the active site. The binding mode of the pantotheine moiety was deduced from superposition studies of Gcdα with 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA dehalogenase and methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase. Besides glutaconyl-CoA, one additional water molecule could be clearly identified within the active site (HOH48) (Figure 5B).

The binding site of the glutaconyl moiety lies in a cavity with two inlets below the crossed helix fingers (Figures 3, 6A and B). The small β-sheets Ib6 and Ib8, as well as the helix Ia6, form the floor of the active site, and the helices Ia7, IIa6 and IIa7 form the ceiling (Figure 5C). To reach the binding pocket, the substrate has to enter a cleft bordered by protein walls formed by the helices Ia2, IIa6 und IIa7. The cleft is covered with positive charges that might guide the negatively charged CoA moiety to the mainly uncharged active site (Figure 4A). The glutaconyl-CoA substrate is only coordinated by residues of the N-terminal domain, although the active site that also encloses the biotin-binding pocket is formed by the N- and the C-terminal domain of different monomers.

Fig. 6. The interaction of the biotin carrier with the Gcdα subunit. (A) Close-up view of the molecular surface of one active site with the model of the Gcdγ C-terminal domain. The binding site of glutaconyl-CoA and biotin is buried by the two helix fingers. (B) The helix fingers are removed compared with (A), and the glutaconyl-CoA residue (magenta) as well as the biotinyllysine residue of the Gcdγ subunit (green) become visible. (C) Stereo view of the active site displaying a model of the Gcdα ternary complex with stick models of glutaconyl-CoA (magenta) and biotin (green). Residues of the N-terminal domain are coloured grey and residues of the C-terminal domain are coloured peach. The amino acids that play a role in the proposed mechanism are labelled, and important hydrogen bridges are represented by black dotted lines. The water that occupies one of the oxyanion holes in the complex is indicated as a blue sphere.

The adenine ring of the glutaconyl-CoA is coordinated by Val151 and Ser149 in the Ib4–Ia5′ loop and binds in a depression on the surface where the pantotheine moiety inserts deeply into the active site. Inside the cavity, the glutaconyl moiety is coordinated by the backbone nitrogens of Val151 and Gly194 as well as HOH48 that forms hydrogen bonds to the glutaconyl-CoA carbonyl oxygen and the backbone nitrogen of Ala457 (Figure 5C). Since the Gcdα–glutaconyl-CoA complex lacks the second substrate biotin, the conformation of the glutaconyl-CoA could differ slightly from the ternary complex. The corresponding potential substrate-binding site in the C-terminal domain provides the binding site for the biotinyllysine and the C-terminal domain of the biotin carrier Gcdγ.

The interaction with the biotin carrier

The Gcdα subunit performs the first step of the glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylation by transferring the CO2 onto biotin, which is covalently attached to the Gcdγ subunit. Therefore, the biotin has to access the active site together with the glutaconyl-CoA substrate in a ternary complex, and the Gcdγ subunit has to interact closely with the Gcdα subunit. Spatial restrictions allow access to the active site by two entrances. Since the entrance towards the central part of the molecule is occupied by the glutaconyl-CoA substrate, the biotinyllysine residue has to enter the active site pocket from the opposite opening on the outer part of the disc-shaped molecule (Figure 6A and B).

The biotin carrier Gcdγ can be divided into the N-terminal globular domain (residues 1–26), the proline–alanine-rich linker region (residues 26–75) and the C-terminal biotin carrier domain (residues 76–146). The latter region forms a five-stranded β-sandwich. In order to demonstrate the interaction of Gcdα with the biotin carrier Gcdγ, a theoretical model of the C-terminal domain of Gcdγ was generated by homology modelling using crystal structures and NMR structures of several known biotin carrier molecules with significant sequence similarity to Gcdγ. In the obtained model, Lys112, the residue that carries the biotin, is located at the tip of a solvent-exposed loop protruding from the sandwich. To evaluate the binding of the biotinyllysine within the active site pocket, an isolated biotin molecule was docked into the empty active site of Gcdα using the program FlexX (BioSolveIT, Germany). The FlexX result locates the biotin within the potential binding pocket of the C-terminal domain whereby the oxygen of the biotin-ureido group lies exactly at the position of HOH48. Since the biotin positioned with FlexX lies very close to the carboxyl group of glutaconyl-CoA, the biotin was manually moved to van der Waals distance to model the ternary complex (Figure 6A).

The theoretical model of the Gcdγ C-terminal domain was positioned on the surface of Gcdα to give a reasonable contact between the biotin and the Lys112 ε-amino group (Figure 6A and B). How the carboxybiotin is protected against hydrolysis during the subsequent transport from the active site of Gcdα into the decarboxylation site in the Gcdβ subunit is still unknown. The postulated interaction of the C-terminal domain of Gcdγ with Gcdα yields no information about the localization of the proline–alanine-rich linker region and the N-terminal domain of Gcdγ within the holoenzyme.

The mechanism of CO2 transfer

O’Keefe and Knowles (1986) thoroughly discussed the mechanisms by which the carboxyl group of glutaconyl-CoA could be reversibly transferred to biotin with retention of the configuration at the methylene carbon (Buckel, 1986). (i) (Rétey and Lynen (1965) proposed a concerted mechanism in which the enol form of biotin donates the proton to the methylene group of glutaconyl-CoA with simultaneous C–C bond cleavage and C–N bond formation. However, double isotope fractionation has shown that the reaction occurs stepwise (O’Keefe and Knowles, 1986). (ii) A base of the enzyme abstracts the proton from N1 of biotin and the resulting anion attacks the carboxylate, leading to carboxybiotin and the dienolate of crotonyl-CoA, which is subsequently protonated by the corresponding acid. (iii) As in (ii) but glutaconyl-CoA spontaneously decarboxylates and the enzyme-bound CO2 is attacked by the biotin anion. Since an attack of a biotin anion on the carboxylate appears less likely than on the electrophilic CO2, the latter mechanism has been preferred in recent reviews (Buckel, 2001b; Attwood and Wallace, 2002). Furthermore, chemical model studies support the transient formation of CO2 (Lihs and Caudle, 2002).

No residue could be detected within the active site of Gcdα, which may act as the postulated base or acid. The water molecule in the complex is irrelevant for the mechanism because it will be substituted by the biotin in the ternary complex. Therefore, we propose that mechanism (iii) has to be modified by a direct transfer of the proton from N1 of biotin to the dienolate, whereby the methyl group of crotonyl-CoA is formed (Figure 7A) (see also Knowles, 1989; Martini and Rétey, 1993). Hence biotin may act as direct proton donor as postulated for the concerted mechanism (i).

Fig. 7. The mechanism of the carboxy transfer and a new model for the holoenzyme. (A) Proposed mechanism of the carboxy transfer. The figures show the different stages of the CO2 transfer from glutaconyl-CoA to biotin as described in the text. (B) Proposed model of the Gcd holoenzyme based on the conclusions deduced from the Gcdα crystal structure. The Gcdα dimer, shown with shadowed helix fingers, contacts the transmembrane channel Gcdβ with the contact region. The location of Gcdδ is based on former models of the Gcd (Braune et al., 1999). The two proposed conformations of Gcdγ are shown. The C-terminal domain of Gcdγ on the left hand side interacts with Gcdα and inserts the biotinyl residue into the active site of Gcdα. The molecule on the right hand side displays the hypothetical rearrangement in the proline–alanine-rich region and transfers the carboxybiotin (triangle) into the active site of the Gcdβ subunit. The interactions of the N-terminal domain and the proline–alanine-rich region of Gcdγ with Gcdα are hypothetical. The black arrows indicate the transport of the sodium ions through the small channels of Gcdα and the ion pump as well as the exit of the released CO2 from the Gcdβ active site through the central channel of Gcdα. The central channel in Gcdα is blocked for sodium ions by positive charges.

The thioester carbonyl is polarized by hydrogen bonds to the backbone amide hydrogen atoms of Val151 and Gly194 that form a first oxyanion hole (Figures 5C and 6C), and a transient decarboxylation of glutaconyl-CoA is induced. The resulting dienolate anion of crotonyl-CoA is additionally stabilized because the interaction with Gly194 locates it in the macrodipole of the Ia6 helix. Glycine residues with an identical localization and function can be found in the 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA dehalogenase (Gly114) and the methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase (Gly110) structures. In a similar way, the acidity of the N1 proton of biotin is enhanced because the negatively charged oxygen of the enolate anion is stabilized in a second oxyanion hole formed by hydrogen bonds to the backbone nitrogens of Ile417, Ala457 and Ala458 (Figure 6C). A small but significant participation of the enol form of biotin (biotin anion) even in the resting state in the absence of substrate could be demonstrated by 13C-NMR (Bendrat et al., 1990).

The transcarboxylation proceeds by transferring the N1-proton to the dienolate anion. The formed biotin anion attacks the carbon dioxide and generates N1-carboxybiotin (Figure 7A). Figure 7A shows the hypothetical reaction mechanism, which has been deduced from the substrate complex.

The hypothesis that the N1 of biotin acts as general acid is supported by the crystal structure of the Gcdα-related carboxyltransferase domain of yeast acetyl-CoA carboxylase that was published during revision of this manuscript (Zhang et al., 2003). The enzyme catalyses the transfer of carbon dioxide from carboxybiotin to acetyl-CoA in a reverse reaction in comparison with Gcdα. Mutagenesis studies on residues in the active site that could function as a general base showed that none of the residues is required for catalysis. Zhang et al. (2003) concluded that the biotin acts as general base.

Conclusions about the holoenzyme

The striking structural and sequential similarity between the two domains of the Gcdα monomer indicates that the domains could have evolved by gene duplication from a common ancestor and developed towards different functions, namely the binding of glutaconyl-CoA or biotin. The high structural similarity of both Gcdα domains to other CoA-binding proteins leads to the suggestion of two possible binding modes for the glutaconyl-CoA substrate in the Gcdα monomer. The experimental Gcdα–gluta conyl-CoA complex shows that the active site of Gcdα comprises the binding site of the glutaconyl-CoA substrate and the binding site of the biotin, whereby the N-terminal domain of Gcdα binds the glutaconyl-CoA substrate and the C-terminal domain provides the binding site for the biotin as well as for the biotin carrier Gcdγ. The active site locates in a cavity formed in the interface of the N-teminal domain and the C-terminal domain of two different monomers. Access to the active site is possible for the negatively charged glutaconyl-CoA substrate by a cleft lined with positive charges (Figure 4A). From the opening opposite the active site, the biotin may enter the cavity via a hydrophobic patch (Figure 6B). The molecular surface opposite to the active site region, also referred to as the contact region, contains a ring-shaped hydrophobic cluster (Figure 4D) involved in a close crystal contact with another crystallographic symmetry-related dimer. From our biochemical data, we conclude that Gcdα exists as a dimer in solution and the interaction with another Gcdα dimer via the contact region is an artefact that probably assists crystallization. Due to the fact that native Gcdα is part of a large protein complex, the hydrophobic ring could serve as interaction site for other Gcd subunits. The functional relationship between the Gcdα subunit and the ion pump Gcdβ leads to the speculation that the hydrophobic ring of the Gcdα dimer serves as an interaction site with the cytoplasmic surface of Gcdβ. The shape and diameter of the hydrophobic ring may bring the central channel of the Gcdα subunit co-axial with the Gcdβ ion channel (Figure 7B). The narrowest region of the central channel is covered with the positive charges of Arg164A, Arg164B, Arg172A and Arg172B that block the channel against cations such as Na+, but passage of the small linear carbon dioxide through the central channel would be facilitated because it can interact with the arginines via four hydrogen bond acceptor sites.

The two smaller channels sideways through the dimer allow for the passage of water and protons. Infiltration of sodium ions would also be possible because potential transient coordination sites exist that provide an incomplete octahedral coordination sphere; however, transport via a spacing between Gcdα and Gcdβ cannot be excluded.

The carboxybiotin decarboxylation site is formed by the Gcdβ subunit and is located at the opposite part of the holoenzyme compared with the transcarboxylation site. The biotin carrier may bridge this distance by extracting the carboxybiotin residue from the active site and transferring it to the decarboxylation site by a structural rearrangement of its rigid proline–alanine-rich linker region. Because of the restricted flexibility, this region could work like a door hinge (Williamson, 1994). The proposed flip mechanism is displayed in Figure 7B.

The oxaloacetate decarboxylase of K.pneumoniae, an enzyme that is closely related to Gcd with the difference that the biotin carrier is fused to the C-terminus of the carboxyltransferase subunit, was shown to be a complex of (α + γ):β:γ = 1:1:1 stoichiometry (Dimroth and Thomer, 1983, 1988). Therefore, and because the Gcdα is found to be dimeric, we conclude that every subunit has to be contained twice in the holoenzyme (Figure 7B).

The crystal structure of the Gcdα subunit and the substrate complex allowed the identification of the active site and the binding sites of the glutaconyl-CoA substrate as well as the modelling of the binding site of the biotin carrier. Confirmation of this model may be achieved by the co-crystallization of the Gcdα and Gcdγ subunits. Thus the crystal structure of the Gcdα subunit of A.fermentans could serve as structural model for carboxyltransferase subunits of known biotin-dependent Na+ pumps from other organisms.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

After expression of gcdA in E.coli (Braune et al., 1999), the Gcdα protein was purified by two rounds of recrystallization. The protein is highly soluble at higher salt concentrations such as 0.5 M NaCl, 150 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, and crystallizes in microcrystals when the salt concentration is lowered by dialysis against water. Finally, the protein was purified by gel filtration on a Superdex™75 26/60 high load column (buffer: 500 mM NaCl, 150 mM phosphate pH 7.5; flow rate 2.5 ml/min) using an FPLC system.

Crystallization and data collection

Before crystallization of the Gcdα, the protein buffer was changed to 3 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0, 500 mM ammonium sulfate using an NAP10 column. Crystals of space group P41212, cell constants a = b = 151.87 Å, c = 163.43 Å and α = β = γ = 90° and two molecules per asymmetric unit grew in a buffer of 0.1 M acetate pH 4.7 and 1.6 M sodium formate, and diffracted to 2.2 Å resolution. The crystals were flash cooled in the 100 K nitrogen stream using a cryo buffer of 40% (v/v) reservoir buffer, 30% (v/v) 4 M ammonium sulfate and 30% (v/v) ethylene glycol. The selenomethionine-labelled Gcdα protein was produced (Budisa et al., 1995) and purified as described previously. To support the identification of the 34 selenium sites per asymmetric unit, the crystals of the selenomethionine-labelled protein were soaked for a further 4 days with a 10 mM solution of platinpterpyridine in crystallization buffer. The diffraction data were collected on the MPG/GBF beamline BW6 at DESY using a MAR-CCD detector. For MAD phasing, diffraction data were collected at different wavelenghts λ1 = 1.07175 (platinum maximal f′), λ2 = 1.0723 (platinum minimal f′′), λ3 = 0.9799 (selenium maximal f′), λ4 = 0.9793 (selenium minimal f′′), λ5 = 0.955 (remote data set), λ6 = 1.0500 (native data set of the selenometionine-labelled protein) (Table I). A high resolution data set of 2.2 Å resolution of the native protein crystals was measured at 1.0500 Å with a crystal rotation of 0.25° per image. The substrate soak was measured at a RIGAKU-rotating anode generator equiped with MAR image plate detector. Data collection and phasing statistics are shown in Table I.

Table I. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data collection | f′′ Pt | f′ Pt | f′′ Se | f′ Se | Remote | Native 1 | Native 2 | Complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.07175 | 1.0723 | 0.9799 | 0.9793 | 0.9500 | 1.0500 | 1.0500 | 1.5418 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.30 | 2.30 | 2.50 | 2.65 | 2.20 | 3.20 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.2 | 99.2 | 97.5 | 98.3 | 97.8 | 99.9 | 99.1 | 90.2 |

| Rmerge (overall) | 7.2 | 7.1 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 9.9 | 6.9 | 12.2 |

| I/σ(I) | 17.1 | 17.3 | 13.1 | 16.1 | 17.0 | 11.8 | 13.7 | 5.6 |

| Phasing | ||||||||

| Phasing power (iso) | 2.170 | 2.183 | – | – | 2.340 | – | – | – |

| Phasing power (ano) | 2.163 | 2.253 | – | – | 1.21 | – | – | – |

| Rcullis (iso) | 0.6266 | 0.6254 | – | – | 0.6242 | – | – | – |

| Refinement statistics | Native | Complex | ||||||

| Maximum resolution (Å) | 2.2 | 3.2 | ||||||

| No. of reflections (overall) | 96 753 | 33 044 | ||||||

| No. of atoms in the asymmetric unit | ||||||||

| Protein | 9020 | 8880 | ||||||

| Ions | 37 | 5 | ||||||

| Solvent | 661 | 193 | ||||||

| Ligand | – | 56 | ||||||

| Main chain dihedral angles in the Ramachandran plot | ||||||||

| Most favoured regions (%) | 88.8 | 82.7 | ||||||

| Additionally allowed regions (%) | 10.0 | 14.7 | ||||||

| Generously allowed regions (%) | 0.8 | 1.8 | ||||||

| Disallowed regions (%) | 0.4 | 0.9 | ||||||

| Rcryst (Rfree) (%)a | 20.1 (22.7) | 18.8 (24.2) | ||||||

| R.m.s.ds | ||||||||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.010 | 0.008 | ||||||

| Angles (°) | 1.3741 | 1.6119 | ||||||

| Bonded B-factors (Å2) | 1.650 | 1.561 | ||||||

| Overall B-factor (Å2) | 35.9 | 24.9 | ||||||

| Protein atoms (Å2) | 35.8 | 25.3 | ||||||

| Main chain atoms (Å2) | 35.0 | 25.1 | ||||||

| Solvent (Å2) | 38.0 | 29.8 |

aRfree was calculated using 5% of the reflections as reference data set.

Structure solution and refinement

The data sets were processed and scaled with the programs DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). The four platinum sites were localized with the program RSPS, and the program Shake&Bake (Weeks and Miller, 1999) was able to localize 27 additional selenium positions. Structure solution was achieved by phasing with the program SHARP (de La Fortelle and Bricogne, 1997) using the four platinum sites and a native data set of SeMet crystals (native 1). The identified selenium sites were used to trace the amino acid sequence during model building. Experimental phases were estimated to a resolution of 2.6 Å, giving a figure of merit of 0.60. After iterative solvent flattening with the program DM (Cowtan, 1994), a final figure of merit of 0.71 was obtained. The solvent-flattened electron density map was sufficient to built the secondary structure elements as a polyalanine model, to determine the NCS operator with the option LSQMAN in O (Jones et al., 1991) and to build a molecular mask with MAMA (Kleywegt and Jones, 1999). The 2-fold averaged map calculated with DM (Cowtan, 1994) using the NCS operator was sufficient to build the whole model except for residues 221–231 in monomer A. These residues are well defined in monomer B, so the chain in molecule A was built according to molecule B but the occupancy of the residues was set to zero during refinement. Model refinement was carried out with CNS49 using the high resolution data set. During alternating refinement cycles performed with simulated annealing in the first round, positional and B-factor refinement in CNS49 and model building in O (Jones et al., 1991), the initial R-factor decreased from 32.1% (Rfree 34.8%) to 26.4% (Rfree 29.6%). After introduction of 661 water molecules, five sulfate ions and four formate ions, the R-factor decreased to 20.1% (Rfree 22.7%). A Ramachandran plot, where 88.8% of the main chain dihedrals are found in the most favoured regions, 10.0% in additional allowed regions, 0.8% in generously allowed regions and 0.4% (four residues) in the disallowed regions, was used to check the geometry of the dimer. The four residues in disallowed regions, Asn162 and Ala193 of both monomers, are very well defined in the electron density, and the geometry distortion appears to be caused by side chain interactions. The secondary structure elements have been assigned as calculated by the programm PROMOTIF (Hutchinson and Thornton, 1996).

Co-crystallization and soaking experiments with biotin and derivatives failed, but freshly grown native crystals could be soaked with a 5 mM solution of glutaconyl-CoA for 12 h. The crystals were mounted in a capillary and measured at 18°C. The native crystals suffer from severe radiation damage when measured at room temperature, but the soaked crystals, that could not be flash cooled, yielded useable data sets. The substrate complex was solved at 3.2 Å resolution using the native Gcdα monomer as search model in AmoRe (Navaza, 1994). Within the electron density of the complex, the residues Ile221–Asp231 are not visible in both monomers. After refinement in CNS (Brünger et al., 1998), model rebuilding in O (Jones et al., 1991) and introduction of 193 water molecules, the R-factor decreased to 18.8% (Rfree 24.2%). The glutaconyl-CoA model was generated in a conformation that corresponds to the ligands in the 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA dehalogenase structure (pdb code 1NZY) (Benning et al., 1996) and the methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase structure (pdb code 1EF8) (Benning et al., 2000) and minimized using SYBYL (MSI, Germany). The model was placed within the one active site into the Fo – Fc density that was assigned to the substrate. The B-values of the substrate have not been refined due to the limited resolution of the substrate complex. Model building and refinement statistics are shown in Table I.

Identification of structurally similar proteins and homology modelling

The program DALI (Holm and Sander, 1993) (r.m.s.d. cut off 3 Å) was used to search for related structures in the RCSB protein databank (Berman et al., 2000). The superpositions of the several structures were performed with the program TOP3D (Guoguang, 2000). The homology modelling of the Gcdγ C-terminal domain has been carried out with the automated protein modelling server SWISS-MODEL (Peitsch, 1996) using the solution structure of the biotin carboxyl carrier domain of the transcarboxylase in Propionibacterium shermanii (pdb code 1DD2) (Reddy et al., 2000), the solution structure of the dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase domain of the pyruvate dehydrogenase fom E.coli (pdb code 1QJO) (Jones et al., 2000), the crystal structure of the biotinyl domain of acetyl-CoA carboxylase from E.coli (pdb code 1BDO) (Athappilly and Hendrickson, 1995) and the solution structure of the holo-biotinyl domain of the acetyl-CoA decarboxylase from E.coli (pdb code 2BDO) (Roberts et al., 1999).

The surface representations have been generated using GRASP (Nicholls et al., 1993) and RASTER3D (Merrit and Murphy, 1994), the backbone plots as well as the electron density representation have been generated with MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis, 1991), BOBSCRIPT and RASTER3D (Merrit and Murphy, 1994), and the alignment was generated with ALSCRIPT (Barton, 1993).

Coordinates

The coordinates and structure factors of the Gcdα structure have been deposited with the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession code 1PIX).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

In memory of Professor Dr Joachim Knappe, the pioneer in the field of biotin-dependent enzymes, who unexpectedly died in June 2003. We thank Annett Braune (Deutsches Institut für Ernährungsforschung, Potsdam-Rehbrücke, Germany) and Petra Fromme (Arizona State University, Tempe, USA) for first crystallization trials with the Gcdα, and we are grateful to Gleb P.Bourenkow and Hans Bartunik at DESY, Hamburg, for data recording and help with the identification of the heavy atom sites. Work in Marburg was supported by grants from the Duetsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

References

- Athappilly F.K. and Hendrickson,W.A. (1995) Structure of the biotinyl domain of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase determined by MAD phasing. Structure, 3, 1407–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood P.V. and Wallace,J.C. (2002) Chemical and catalytical mechanisms of carboxyl transfer reactions in biotin-dependent enzymes. Acc. Chem. Res., 35, 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton G.J. (1993) ALSCRIPT: a tool to format multiple sequence alignments. Protein Eng., 6, 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendrat K., Berger,S., Buckel,W., Etzel,W.A. and Röhm,K.H. (1990) Carbon-13 labelled biotin—a new probe for the study of enzyme catalyzed carboxylation and decarboxylation reactions. FEBS Lett., 277, 156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning M.M., Taylor,K.L., Liu,R.Q., Yang,G., Xiang,H., Wesenberg,G., Dunaway-Mariano,D. and Holden,H.M. (1996) Structure of 4-chlorobenzoyl coenzyme A dehalogenase determined to 1.8 Å resolution: an enzyme catalyst generated via adaptive mutation. Biochemistry, 35, 8103–8109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning M.M., Haller,T., Gerlt,J.A. and Holden,H.M. (2000) New reactions in the crotonase superfamily: structure of methylmalonyl CoA decarboxylase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 39, 4630–4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S., Braune,A., Buckel,W., Härtel,U. and Lee,M.-L. (1996) Enzyme catalyzed formation of carboxybiotin as proven by the measurement of 15N, 13C and 13C, 13C, spin–spin coupling. Angew. Chem Int. Edn., 35, 2135–2133. [Google Scholar]

- Berman H.M., Westbrook,J., Feng,Z., Gilliland,G., Bhat,T.N., Weissig,H., Shindyalov,I.N. and Bourne,P.E. (2000) The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bott M., Pfister,K., Burda,P., Kalbermatter,O., Woehlke,G. and Dimroth,P. (1997) Methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase from Propionigenium modestum—cloning and sequencing of the structural genes and purification of the enzyme complex. Eur. J. Biochem., 250, 590–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braune A., Bendrat,K., Rospert,S. and Buckel,W. (1999) The sodium ion translocating glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase from Acidaminococcus fermentans: cloning and function of the genes forming a second operon. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 473–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. (1980) Analysis of the fermentation pathways of clostridia using double labelled glutamate. Arch. Microbiol., 127, 167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. (1986) Substrate stereochemistry of the biotin-dependent sodium pump glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase from Acidaminococcus fermentans. Eur. J. Biochem., 156, 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. (2001a) Unusual enzymes involved in five pathways of glutamate fermentation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 57, 263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. (2001b) Sodium ion-translocating decarboxylases. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 1505, 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. and Barker,H.A. (1974) Two pathways of glutamate fermentation by anaerobic bacteria. J. Bacteriol., 117, 1248–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. and Liedtke,H. (1986) The sodium pump glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase from Acidaminococcus fermentans. Specific cleavage by n-alkanols. Eur. J. Biochem., 156, 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. and Semmler,R. (1982) A biotin-dependent sodium pump: glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase from Acidaminococcus fermentans. FEBS Lett., 148, 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W. and Semmler,R. (1983) Purification, characterisation and reconstitution of glutaconyl-CoA decarboxylase, a biotin-dependent sodium pump from anaerobic bacteria. Eur. J. Biochem., 136, 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budisa N., Steipe,B., Demange,P., Eckerskorn,C., Kellermann,J. and Huber,R. (1995) High-level biosynthetic substitution of methionine in proteins by its analogs 2-aminohexanoic acid, selenomethionine, telluromethionine and ethionine in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem., 230, 788–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K. (1994) ‘dm’: an automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newslett. Protein Crystallogr., 31, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- de La Fortelle E. and Bricogne,G. (1997) Macromolecular crystallo graphy. Methods Enzymol., 276, pp. 472–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Berardino M. and Dimroth,P. (1996) Aspartate 203 of the oxaloacetate decarboxylase β-subunit catalyses both the chemical and vectorial reaction of the Na+ pump. EMBO J., 15, 1842–1849. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth P. (1990) Bacterial energy transductions coupled to sodium ions. Res. Microbiol., 141, 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth P. and Thomer,A. (1983) Subunit composition of oxaloacetate decarboxylase and characterization of the α chain as carboxyltransferase. Eur. J. Biochem., 137, 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth P. and Thomer,A. (1988) Dissociation of the sodium-ion-translocating oxaloacetate decarboxylase of Klebsiella pneumoniae and reconstitution of the active complex from the isolated subunits. Eur. J. Biochem., 175, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth P., Jockel,P. and Schmid,M. (2001) Coupling mechanism of the oxaloacetate decarboxylase Na(+) pump. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 1505, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guoguang L. (2000) A new method for protein structure comparisons and similarity searches. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 33, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Härtel U. and Buckel,W. (1996) Sodium ion-dependent hydrogen production in Acidaminococcus fermentans. Arch. Microbiol., 166, 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert W. and Dimroth,P. (1983) Purification and characterization of a new sodium-transport decarboxylase. Methylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase from Veillonella alcalescens. Eur. J. Biochem., 132, 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L. and Sander,C. (1993) Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol., 233, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson E.G. and Thornton,J.M. (1996) PROMOTIF—a program to identify and analyze structural motifs in proteins. Protein Sci., 5, 212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.D., Stott,K.M., Howard,M.J. and Perham,R.N. (2000) Restricted motion of the lipoyl-lysine swinging arm in the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 39, 8448–8459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou,J.Y., Cowan,S.W. and Kjeldgaard,M. (1991) Improved methods for binding protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt G.J. and Jones,T.A. (1999) Software for handling macromolecular envelopes. Acta Crystallogr. D, 55, 941–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles J.R. (1989) The mechanism of biotin-dependent enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 58, 195–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P.J. (1991) MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 24, 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lihs F.J. and Caudle,M.T. (2002) Kinetics and mechanism for CO2 scrambling in a N1-carboxyimidazolidone analogue for N1-carboxybiotin. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 11334–11341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini H. and Rétey,J. (1993) Propionyl-aza(dethia)coenzyme A as pseudosubstrate of the biotin-containing transcarboxylase. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn., 32, 278–280. [Google Scholar]

- Merrit E.A. and Murphy,M.E.P. (1994) Raster3D Version 2.0 a program for photorealistic molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D, 50, 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y., Filppula,S.A., Novikov,D.K., Norledge,B., Hiltunen,J.K. and Wierenga,R.K. (1998) The crystal structure of dienoyl-CoA isomerase at 1.5 Å resolution reveals the importance of aspartate and glutamate sidechains for catalysis. Structure, 6, 957–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mursula A.M., van Aalten,D.M., Modis,Y., Hiltunen,J.K. and Wierenga,R.K. (2000) Crystallization and X-ray diffraction analysis of peroxisomal Δ3-Δ2-enoyl-CoA isomerase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Acta Crystallogr. D, 56, 1020–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. (1994) Amore: an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. A, 50, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls A., Bharadwaj,R. and Honig,B. (1993) GRASP—graphical representation and analysis of surface properties. Biophys. J., 64, A166. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe S.J. and Knowles,J.R. (1986) Biotin-dependent carboxylation catalyzed by transcarboxylase is a stepwise process. Biochemistry, 25, 6077–6084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. and Minor,W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitsch M.C. (1996) ProMod and Swiss-Model: Internet-based tools for automated comparative protein modelling. Biochem. Soc. Trans, 24, 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy D.V., Shenoy,B.C., Carey,P.R. and Sonnichsen,F.D. (2000) High resolution solution structure of the 1.3S subunit of transcarboxylase from Propionibacterium shermanii. Biochemistry, 39, 2509–2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rétey J. and Lynen,F. (1965) On the biochemical function of biotin. IX. The steric course in the carboxylation of propionyl-CoA. Biochem. Z., 342, 256–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E.L., Shu,N., Howard,M.J., Broadhurst,R.W., Chapman-Smith,A., Wallace,J.C., Morris,T., Cronan,J.E.,Jr and Perham,R.N. (1999) Solution structures of apo and holo biotinyl domains from acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase of Escherichia coli determined by triple-resonance nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry, 38, 5045–5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks C.M. and Miller,R. (1999) Optimizing Shake-and-Bake for proteins. Acta Crystallogr. D, 55, 492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M.P. (1994) The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem. J., 297, 249–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Yang,Z., Shen,Y. and Tong,L. (2003) Crystal structure of the carboxyltransferase domain of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase. Science, 299, 2064–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]