Abstract

Budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) origin recognition complex (ORC) requires ATP to bind specific DNA sequences, whereas fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) ORC binds to specific, asymmetric A:T-rich sites within replication origins, independently of ATP, and frog (Xenopus laevis) ORC seems to bind DNA non-specifically. Here we show that despite these differences, ORCs are functionally conserved. Firstly, SpOrc1, SpOrc4 and SpOrc5, like those from other eukaryotes, bound ATP and exhibited ATPase activity, suggesting that ATP is required for pre-replication complex (pre-RC) assembly rather than origin specificity. Secondly, SpOrc4, which is solely responsible for binding SpORC to DNA, inhibited up to 70% of XlORC-dependent DNA replication in Xenopus egg extract by preventing XlORC from binding to chromatin and assembling pre-RCs. Chromatin-bound SpOrc4 was located at AT-rich sequences. XlORC in egg extract bound preferentially to asymmetric A:T-sequences in either bare DNA or in sperm chromatin, and it recruited XlCdc6 and XlMcm proteins to these sequences. These results reveal that XlORC initiates DNA replication preferentially at the same or similar sites to those targeted in S.pombe.

Keywords: AT-rich sequences/ATPase/DNA replication origin/Orc4/ORC–DNA binding

Introduction

DNA replication begins when a six subunit complex called the ‘origin recognition complex’ (ORC) binds to DNA and initiates assembly of a pre-replication complex (pre-RC) consisting of proteins including ORC, Cdc6(Cdc18), Cdt1 and Mcm 2–7 (Bell and Dutta, 2002). Site-specific initiation of DNA replication has not been detected in frog eggs or egg extracts (Hyrien et al., 1995; Blow et al., 2001), but in yeast, flies and mammals, DNA replication generally begins at specific genomic sites (replication origins) that are determined by cis-acting sequences (DePamphilis, 1999; Altman and Fanning, 2001; Bell and Dutta, 2002; Kong and DePamphilis, 2002; and references therein). However, efforts to elucidate the mechanism of site selection using purified ORCs have met with limited success. The budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, uses five of its ORC subunits [Orc(1–5)] to recognize a specific 11 bp AT-rich sequence and this event requires ATP (Lee and Bell, 1997), but in the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the Orc4 subunit is solely responsible for binding ORC to specific asymmetric A:T-rich sequences within S.pombe replication origins in vivo as well as in vitro, and this event does not require ATP (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001, 2002; Lee et al., 2001). A small fraction of ORC from the fly, Drosophila melanogaster, binds selectively to AT-rich replication elements either in D.melanogaster (Austin et al., 1999) or Sciara coprophila (Bielinsky et al., 2001) amplification origins, and like its S.cerevisiae counterpart, this binding is ATP-dependent. However, the bulk of purified DmORC binds DNA non-specifically (Austin et al., 1999; Chesnokov et al., 2001). Human ORC has not been reported to exhibit sequence-specific DNA binding in vitro, although in vivo, it is found at specific genomic sites (Keller et al., 2002; Ladenburger et al., 2002).

To determine the extent to which metazoan ORCs initiate DNA replication at specific genomic sites, we incubated Xenopus laevis sperm chromatin in a X.laevis egg extract and challenged the resulting XlORC- dependent DNA replication with S.pombe Orc4 protein. Schizosaccharomyces pombe replication origins are more similar to origins in flies (Austin et al., 1999; Bielinsky et al., 2001; Ina et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2001) and mammals (Abdurashidova et al., 2000; Altman and Fanning, 2001) than to origins in S.cerevisiae (Bell and Dutta, 2002). Therefore, it was possible that SpOrc4 would compete with some or all of the XlORC for binding to the same sites in sperm chromatin. Furthermore, while all of these replication origins are genetically required for site-specific initiation of DNA replication in their respective organism, those in S.pombe, flies and mammals differ significantly from those in S.cerevisiae. They are five to ten times larger than those in S.cerevisiae. They are not interchangeable with S.cerevisiae origins. They contain large AT-rich sequences and they lack an identifiable consensus sequence that is genetically required for origin activity.

Each of the four S.pombe replication origins analyzed so far contain two or more regions that are required for full ARS activity (Kim and Huberman, 1999; Okuno et al., 1999; and references therein). They consist of asymmetric A:T-rich sequences with A residues clustered on one strand and T residues on the other. Some required regions also exhibit either orientation (Kim and Huberman, 1998) or distance (Kong and DePamphilis, 2002) dependence. Moreover, some required regions bind SpORC (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001, 2002; Lee et al., 2001), assemble a pre-RC and initiate bi-directional DNA replication, while others with the same AT-content do not (Kong and DePamphilis, 2002).

The N-terminal half of SpOrc4 contains nine AT-hook motifs that specifically bind AT-rich sequences, while the C-terminal half is 35% identical and 63% similar to the human and Xenopus Orc4 proteins (Chuang and Kelly, 1999; Moon et al., 1999). However, while SpOrc4 has a general affinity for all AT-rich DNA, it has a higher affinity for specific asymmetric A:T-rich sequences found within S.pombe replication origins (Okuno et al., 1999; Kong and DePamphilis, 2001, 2002; Lee et al., 2001; Takahashi and Masukata, 2001; Takahashi et al., 2003) and initiates bi-directional DNA replication primarily at a single site within the ARS element (Gomez and Antequera, 1999; Kong and DePamphilis, 2002; Takahashi et al., 2003). Thus, while each AT-hook motif binds tightly to [AAA(T/A)], site specificity probably results from the arrangement of all nine motifs acting in concert. SpOrc4 recruits the remaining five ORC subunits to the DNA-binding site and initiates assembly of a pre-RC.

The results presented here support the view that eukaryotic ORCs are functionally, if not structurally, conserved, and preferentially recognize the same AT-rich sequences. Firstly, SpOrc1, SpOrc4 and SpOrc5, like those from other eukaryotes, bound ATP and exhibited ATPase activity. Since SpOrc4 is solely required for site-specific DNA binding in S.pombe, and since this binding is not ATP-dependent, these activities are likely to be required for pre-RC assembly rather than for origin selection. Secondly, addition of purified SpOrc4 to Xenopus egg extracts inhibited up to 70% of the XlORC-dependent DNA replication in Xenopus sperm chromatin. This inhibition required the DNA-binding domain of SpOrc4, and all of the chromatin-bound SpOrc4 in these extracts was located at AT-rich sequences. SpOrc4 neither replaced the XlOrc4 subunit in XlORCs, nor disrupted pre-RCs once they had been assembled, nor interfered with ongoing DNA synthesis. XlORC (like SpOrc4) preferentially bound to asymmetric A:T sequences both in DNA and in sperm chromatin, and in addition, recruited XlCdc6 and XlMcm proteins. These results reveal that, under DNA replication conditions, XlORC and SpORC share the same strong preference for AT-rich sequences, and suggest that fission yeast is an appropriate paradigm for DNA replication in the metazoa.

Results

Schizosaccharomyces pombe ORC subunits 1, 4 and 5 each bind ATP

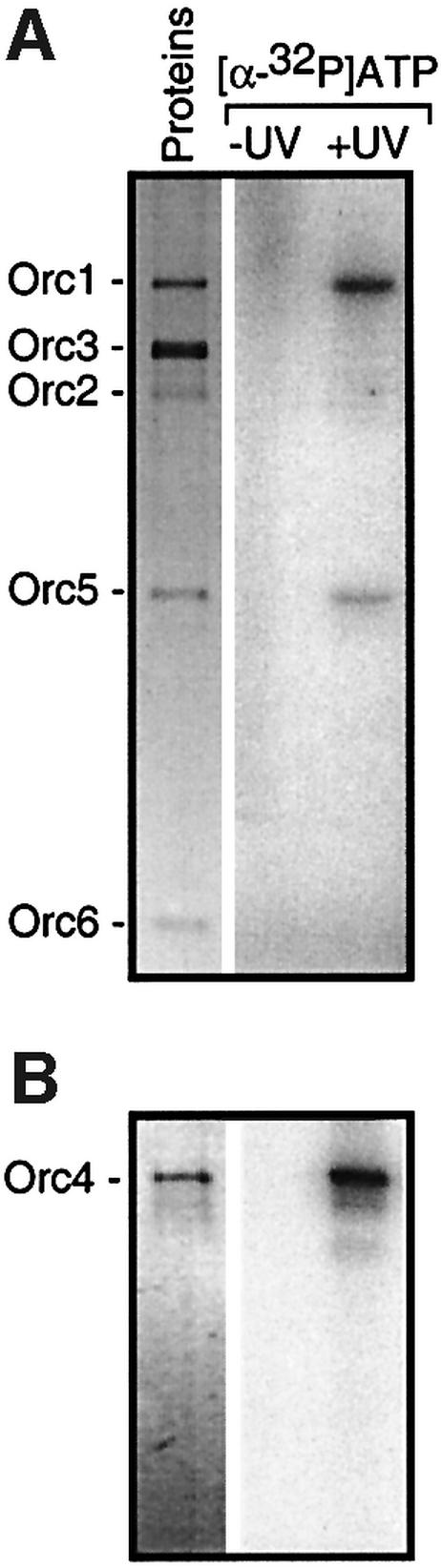

To determine whether or not eukaryotic ORCs are functionally conserved, the ability of SpORC to bind and hydrolyze ATP was examined. Since the amino acid sequences of Orc1, Orc4 and Orc5 in all species characterized so far each contain potential ATP-binding sites (Walker A and B motifs), the role of ATP and ATPase activity in ORC function is presumed to be universal (Bell and Dutta, 2002). However, ATP binding and ATPase activity have been reported only in S.cerevisiae (Klemm et al., 1997) and D.melanogaster (Chesnokov et al., 2001). Therefore, to determine whether or not S.pombe ORC subunits actually bind ATP, purified SpOrc4 and a purified ORC-5 complex containing an equimolar ratio of SpOrc1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 were incubated with [α-32P]ATP, subjected to UV irradiation in order to crosslink ATP to its binding sites, and then fractionated by SDS gel electrophoresis in order to identify 32P-labeled proteins. [α-32P]ATP was used instead of [γ-32P]ATP to avoid confusion between ATP binding and protein phosphorylation. The results showed that ATP bound only to Orc1, Orc4 and Orc5 (Figure 1), consistent with the presence of Walker A and B amino acid sequence motifs in these proteins. Moreover, the difference in the intensities of the [32P]Orc1 and [32P]Orc5 bands (Figure 1A) indicated that the binding efficiency of ATP was ∼3.7-fold greater to Orc1 than to Orc5, consistent with the fact that Orc1 contains a perfect match to the Walker A motif whereas Orc5 contains only three of the five critical amino acids.

Fig. 1. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Orc1, Orc4 and Orc5-bound ATP. Purified ORC-5 complex containing Orc1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 (A) and purified SpOrc4 (B) was subjected to a UV-crosslinking (+UV) in the presence of [α-32P]ATP. Only Orc1, Orc4 and Orc5 were radiolabeled. ‘Proteins’ were stained with silver. In gels stained with Coomassie Blue (data not shown), the ratio of subunits in the ORC-5 complex was equimolar.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe ORC hydrolyzes ATP

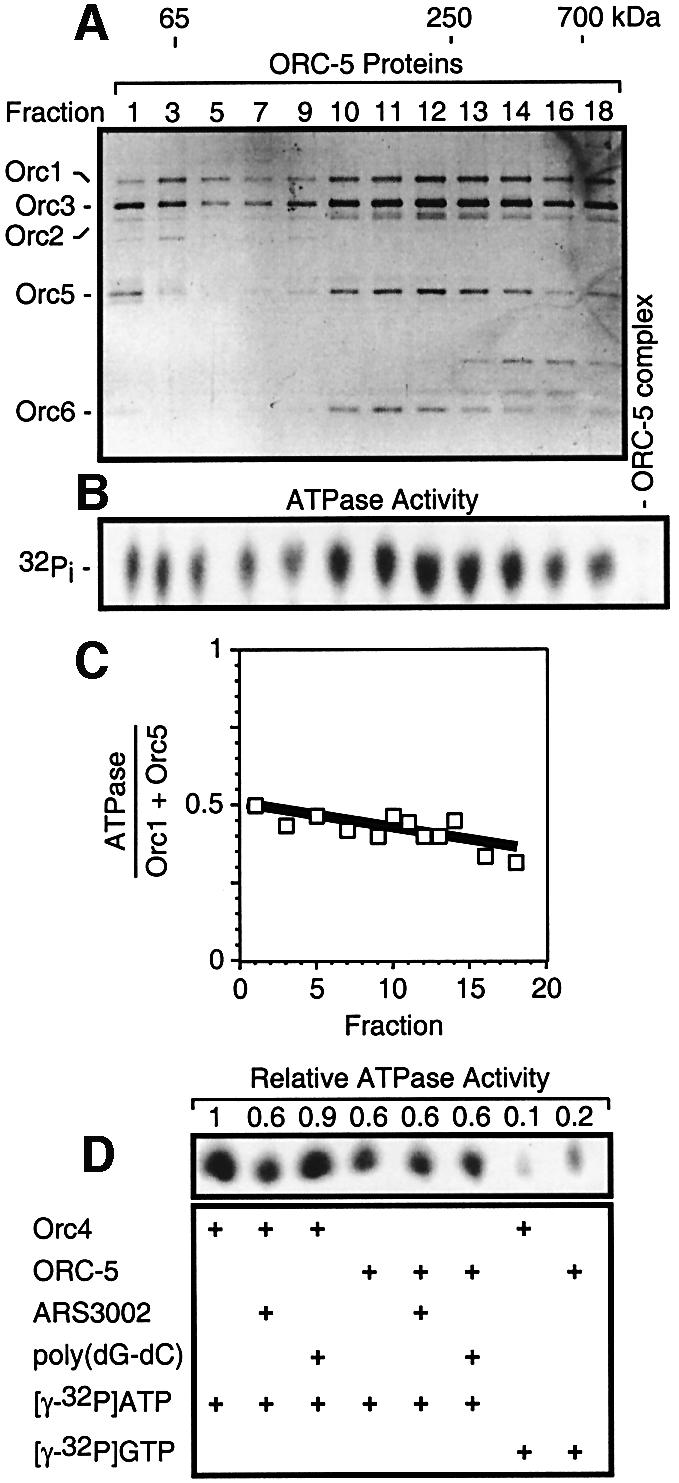

To determine whether or not SpORC subunits exhibit ATPase activity as well as bind ATP, the ORC-5 complex was fractionated by glycerol gradient sedimentation and individual fractions assayed for Orc proteins by gel electrophoresis (Figure 2A) and for ATPase activity by release of inorganic phosphate (Figure 2B). ATPase activity was greatest in the range of ∼250 kDa (fractions 10–14), consistent with the calculated size of the ORC-5 complex (∼300 kDa). ATPase activity in each fraction was proportional to the amounts of Orc1 and Orc5 protein present (Figure 2C). Since Orc1 and Orc5 were the only two subunits in the ORC-5 complex that bound ATP, these results suggested that the ATPase activity resulted from these two proteins.

Fig. 2. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Orc proteins exhibited ATPase activity. ORC-5 complex was fractionated by sedimentation through a neutral glycerol gradient. (A) Aliquots from individual fractions were assayed for protein composition by SDS gel electrophoresis followed by silver staining. Molecular weight standards were fractionated in parallel (BSA, 65 kDa; catalase, 250 kDa; thyroglobulin, 700 kDa). (B) Aliquots were assayed for ATPase activity by their ability to release 32Pi from [γ-32P]ATP (1 h time point). ‘Minus ORC-5’ was a control without the ORC-5 complex. (C) Ratio of ATPase activity to Orc1 plus Orc5 protein was calculated from densitometry data (SEM was ±10%). (D) SpOrc4 (50 ng) or ORC-5 complex (40 ng) was mixed with 1 µl [γ-32P]ATP either in the presence or absence of 500 ng S.pombe ARS3002 900 bp DNA fragment (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001) or 500 ng poly(dG-dC)·(dC-dG) and assayed for ATPase activity.

Purified SpOrc4 protein also exhibited ATPase activity (∼0.02 pmol/min/pmol protein) similar to the specific activity of the ORC-5 complex (∼0.04 pmol/min/pmol protein). GTP did not substitute for ATP, and either S.pombe ARS3002 DNA or poly(dA)·poly(dT) (data not shown) inhibited SpOrc4 ATPase ∼40%, while poly(dG-dC)·poly(dC-dG) inhibited SpOrc4 ATPase ∼10% (Figure 2D). The same results were obtained from 15–90 min of incubation. Neither DNA inhibited ATPase activity in the ORC-5 complex. Since SpOrc4 binds strongly to S.pombe replication origins and weakly to GC-rich DNA, and ORC-5 complex binds weakly to all DNA (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001, 2002; Lee et al., 2001), these results are consistent with previous studies in S.cerevisiae showing that ATPase activity is inhibited when ORC binds to a replication origin (Klemm et al., 1997).

Schizosaccharomyces pombe Orc4 inhibits DNA replication in Xenopus egg extract

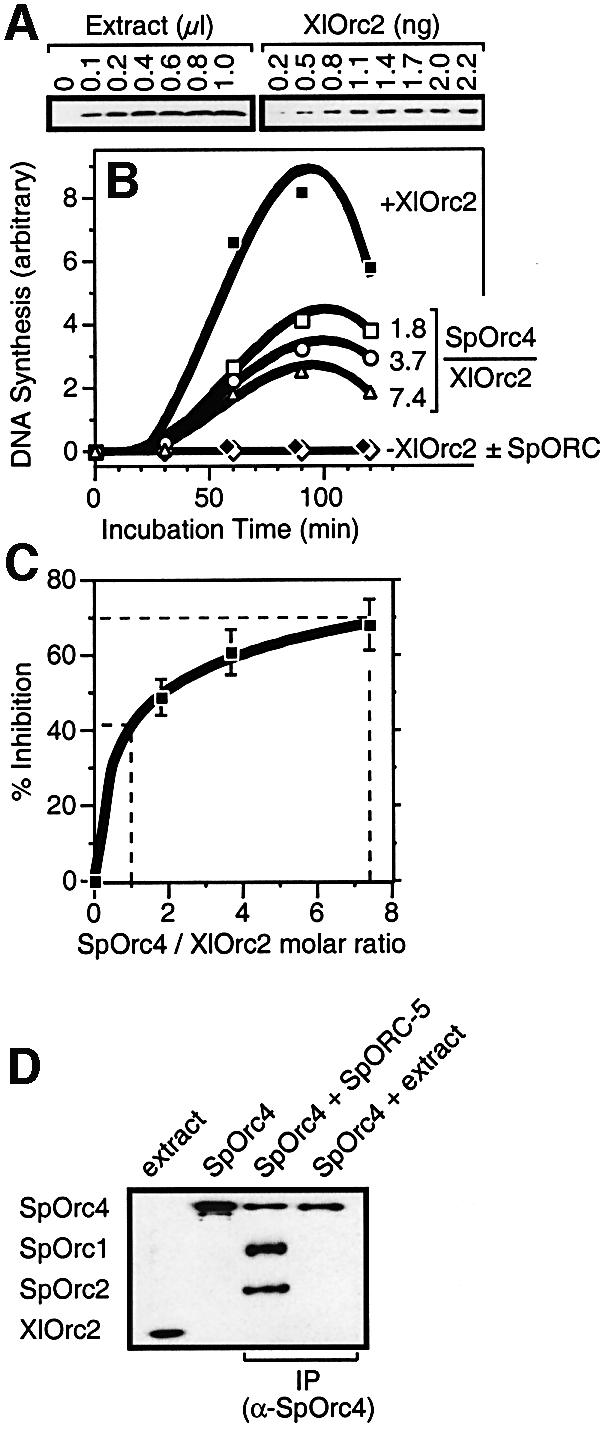

Previous studies have shown that immunodepletion of either Orc1 or Orc2 from Xenopus egg extracts prevents initiation of DNA replication by co-precipitating most, if not all, of the other ORC subunits, and that activity is restored by addition of XlORC (Carpenter et al., 1996; Coleman et al., 1996; Romanowski et al., 1996; Rowles et al., 1996; Tugal et al., 1998). Therefore, initiation of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extract is dependent on a functional interaction between ORC and chromatin. This conclusion was confirmed with XlOrc2-depleted Xenopus egg extract, and extended to reveal that addition of SpOrc4 together with ORC-5 complex to XlOrc2-depleted egg extract did not restore DNA replication activity (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. SpOrc4 inhibited XlORC-dependent DNA replication. (A) The amount of XlOrc2 protein in Xenopus egg extract was determined by fractionating extract by SDS gel electrophoresis in parallel with purified XlOrc2 protein and then immunoblotting with anti-XlOrc2 antiserum. Proteins were identified by their size and immunospecificity. (B) DNA synthesis in Xenopus sperm chromatin was measured in Xenopus egg extract diluted 10-fold with XlOrc2-depleted extract. SpOrc4 (125 kDa) was added to extract (0, 16, 32 and 64 ng, respectively) containing 4.5 ng XlOrc2 (65 kDa), to give molar ratios of SpOrc4/XlOrc2 of 0 (filled square), 1.8 (open square), 3.7 (open circle) and 7.4 (open triangle). Sperm chromatin was then added, and the mixture incubated for the times indicated before measuring acid-insoluble [32P]DNA. In the absence of SpOrc4, 20–30% of template DNA was replicated by 90 min of incubation (+XlOrc2). DNA replication was not detected either in XlOrc2-depleted extract (open diamond) or in XlOrc2- depleted extract supplemented with SpORC (filled diamond). (C) Percent inhibition was calculated from the 90 min data in (B). Dashed lines indicate 40–70% inhibition. (D) SpOrc4 was mixed either with an equimolar amount of ORC-5 complex, or with high-speed supernatant from Xenopus egg extract (molar ratio SpOrc4/XlOrc2 = 1). Immunoprecipitation (IP) was then carried out with anti-SpOrc4 antibodies crosslinked to Protein A–agarose beads, and the proteins in the IP fractionated by SDS gel electrophoresis and detected by immunoblotting (Harlow and Lane, 1999). Lanes labeled ‘extract’ and SpOrc4 were the starting materials.

To determine whether or not SpOrc4 competes with XlORC for the same initiation sites, the amount of XlORC was reduced 10-fold by combining 90% of a XlORC-depleted extract with 10% of a whole egg extract. This reduced the ratio of XlORC to DNA, thereby increasing any preference for specific DNA sites, and it reduced the amount of SpOrc4 required to achieve molar ratios with XlOrc proteins of 1 or greater. Under these conditions, DNA synthesis was reduced ∼10% compared with whole egg extract, and the ratios of SpOrc4 to DNA were similar to those previously used to detect site-specific binding of SpOrc4 to S.pombe replication origins in DNA band shift assays and DNase I footprinting analyses (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001, 2002).

Ratios of SpOrc4 to XlOrc2 protein were determined by measuring the amount of XlOrc2 protein in aliquots of egg extract and comparing these results directly with known amounts of purified XlOrc2 protein (Figure 3A). Addition of purified SpOrc4 protein to egg extract inhibited XlORC-dependent DNA replication (Figure 3B) such that DNA synthesis was inhibited ∼40% by the presence of equimolar concentrations of SpOrc4 and XlOrc2 proteins, and ∼70% when the molar ratio of SpOrc4 to XlORC was 7.4 (Figure 3C). These results suggested that up to 70% of XlORC bound preferentially to the same AT-rich sequences targeted by SpORC.

Alternatively, inhibition of ORC-dependent DNA replication may have resulted from disruption of XlORC by SpOrc4 protein. This possibility was excluded in two ways. Firstly, inhibition of DNA replication by SpOrc4 was not proportional to the amount of SpOrc4 added, but reached a plateau of ∼70% (Figure 3C). Secondly, immunoprecipitation of SpOrc4 from egg extract did not precipitate XlOrc2, whereas immunoprecipitation of SpOrc4 in the presence of SpOrc1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 subunits (the ORC-5 complex) did precipitate SpOrc1 and SpOrc2 (Figure 3D). Therefore, SpOrc4 did not inhibit XlORC function by replacing XlOrc4.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe Orc4 inhibits initiation of DNA replication

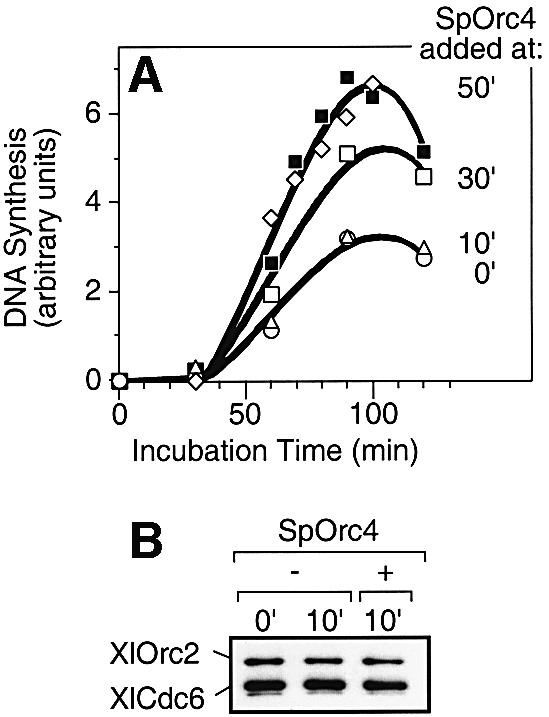

To determine whether SpOrc4 inhibited initiation of DNA replication rather than DNA synthesis at replication forks, a 3.7 molar excess of SpOrc4 was added to egg extract at different times following addition of sperm chromatin. When SpOrc4 was added either with the chromatin (t = 0 min) or 10 min later, DNA synthesis was reduced ∼55% (Figure 4A). However, when SpOrc4 was added 30 min after the chromatin (10–15 min before DNA synthesis was detected), then DNA replication was reduced only 25%. When SpOrc4 was added 50 min after chromatin, no inhibition was observed, suggesting that SpOrc4 specifically inhibited assembly of pre-RCs.

Fig. 4. Pre-RCs that were assembled prior to addition of SpOrc4 were not disrupted. (A) Sperm chromatin was incubated in egg extract either in the absence (filled square) or in the presence of SpOrc4 (open symbols). SpOrc4 was added at 0 (open circle), 10 (open triangle), 30 (open square) or 50 (open diamond) min after sperm chromatin. (B) Xenopus sperm chromatin was first incubated with the high-speed supernatant from an egg extract for 45 min. The sample was then divided into three portions. One portion was placed on ice (0′). One portion was incubated for an additional 10 min (10′). One portion was supplemented with SpOrc4 at a molar ratio with XlOrc2 of 3.7 and then incubated for an additional 10 min. Chromatin was isolated from each sample, fractionated by SDS gel electrophoresis, and the amounts of XlOrc2 and XlCdc6 determined by immunoblotting.

The inhibition observed when SpOrc4 was added 30 min into the incubation resulted either from asynchronous initiation, or from disruption of pre-RCs already on the chromatin. To distinguish between these two possibilities, sperm chromatin was first incubated in the high speed supernatant fraction from an egg extract for 45 min, and then the amounts of XlOrc2 and XlCdc6 bound to the sperm chromatin were measured before and 10 min after addition of SpOrc4. Under these conditions, pre-RCs are assembled on sperm chromatin, but they are not activated, because a nucleus cannot be assembled in the absence of the membrane vesicles (Walter et al., 1998). No change was detected in the amounts of chromatin-bound XlOrc2 and XlCdc6, and therefore no change occurred in the number of pre-RCs present (Figure 4B). Therefore, inhibition of XlORC-dependent DNA replication by SpOrc4 must occur prior to pre-RC assembly. Moreover, the same amount of DNA synthesis was detected whether the membrane fraction alone or the membrane fraction together with SpOrc4 was added to a 50 min preincubation of membrane-free extract and sperm chromatin (data not shown). Therefore, SpOrc4 did not inhibit DNA synthesis once Xenopus pre-RCs had been assembled.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe Orc4 competes for Xenopus ORC DNA-binding sites

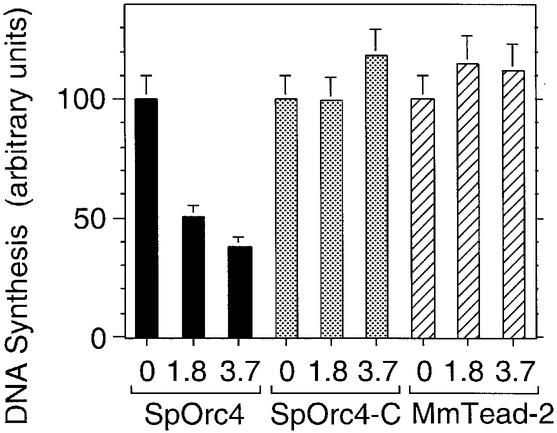

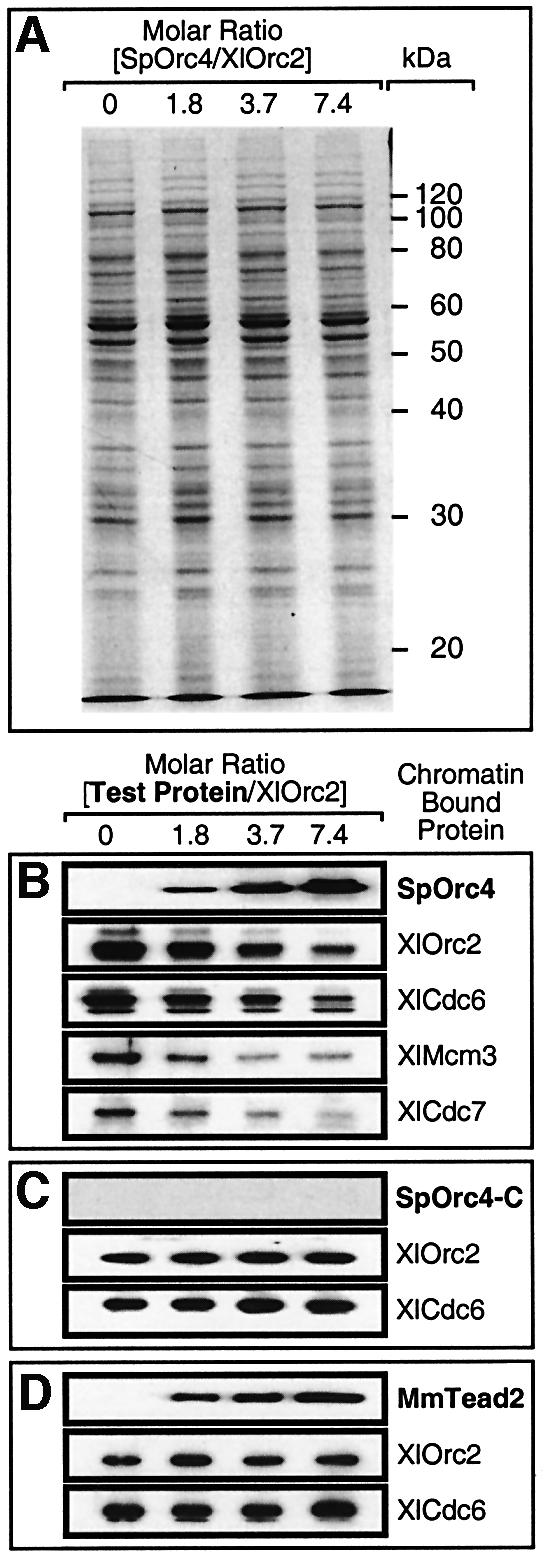

To determine whether or not inhibition of XlORC- dependent DNA replication by SpOrc4 resulted from competition for ORC DNA-binding sites, a truncated SpOrc4 (SpOrc4-C) containing the C-terminal half (aa515–aa972) but lacking all nine AT-hook motifs was tested for its ability to inhibit XlORC-dependent DNA replication. SpOrc4-C does not bind DNA (Chuang and Kelly, 1999), and it did not inhibit DNA synthesis (Figure 5). Therefore, inhibition of XlORC-dependent DNA replication by SpOrc4 required that SpOrc4 bind DNA. Moreover, this DNA binding was sequence-dependent. Mouse Tead2 is a transcription factor that binds predominantly to GGAATG (Kaneko and DePamphilis, 1998) as well as to several other sites that give a consensus of G(A)GA(T/C)ATG (Jiang et al., 2000). In contrast to SpOrc4, MmTead2 did not interfere with XlORC-dependent DNA replication (Figure 5), suggesting that SpOrc4 and XlORC share in common a group of DNA-binding sites that do not include those sites recognized by MmTead2.

Fig. 5. Inhibition of Xenopus ORC-dependent DNA synthesis was dependent on sequence-specific binding of SpOrc4. Either SpOrc4, SpOrc4-C or MmTead2 was added to Xenopus egg extract at the indicated molar ratio to XlOrc2, and the mixture incubated with sperm chromatin for 90 min. SpOrc4-C lacks the AT-hook domains. MmTead2 binds to a different sequence than does SpOrc4.

To test this hypothesis directly, sperm chromatin was incubated in egg extract for 20 min in the presence of various amounts of SpOrc4. Chromatin was isolated and chromatin-bound proteins were fractionated by SDS gel electrophoresis. As the amount of chromatin-bound SpOrc4 was increased, the overall pattern of chromatin-bound proteins remained unchanged (Figure 6A), but the amounts of chromatin-bound XlOrc2, XlCdc6, XlMcm3 and XlCdc7 proteins decreased (Figure 6B). Orc2, Cdc6 and Mcm3 proteins are three of the proteins that comprise pre-RCs, and Cdc7 is one of the proteins required to activate pre-RCs (Bell and Dutta, 2002). Moreover, the decrease in chromatin-bound XlOrc2 was proportional to the decrease in DNA synthesis. At molar ratios of SpOrc4 to XlOrc2 of 3.7 and 7.4, chromatin-bound XlOrc2 was reduced ∼60 and ∼80%, respectively, while DNA synthesis was reduced ∼55 and ∼70%, respectively.

Fig. 6. SpOrc4 specifically inhibited binding of XlORC to sperm chromatin and assembly of pre-RCs. Sperm chromatin was incubated in egg extract supplemented with the indicated amounts of SpOrc4, SpOrc4-C or MmTead2, as previously described for measuring DNA synthesis. After 20 min, chromatin was isolated and chromatin-bound proteins were fractionated by SDS–PAGE. (A) Proteins were stained with Coomassie Blue. (B–D) The indicated protein was detected by immunoblotting with the appropriate antibody. Antibody prepared against SpOrc4-C detected SpOrc4-C in western blots.

As expected, SpOrc4-C did not bind sperm chromatin, so it did not affect the binding of XlORC or XlCdc6 protein (Figure 6C). MmTead2, however, did bind sperm chromatin, but it did not interfere with binding of XlOrc2 or XlCdc6 (Figure 6D), presumably because it did not bind to the same sites selected by XlORC. Both results were consistent with the inability of these two proteins to inhibit XlORC-dependent DNA replication. Taken together, the results presented in Figures 3–6 strongly suggest that inhibition of XlORC-dependent DNA replication by SpOrc4 results from direct competition for specific DNA-binding sites in chromatin.

SpOrc4 preferentially binds to AT-rich sequences in chromatin

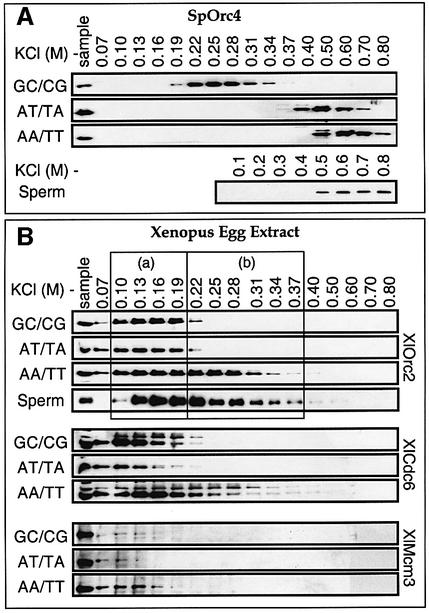

To determine directly whether or not SpOrc4 preferentially bound to AT-rich sequences when incubated with sperm chromatin in Xenopus egg extract, the salt concentration required to elute SpOrc4 from sperm chromatin was compared with the salt concentration required to elute SpOrc4 from specific DNA sequences. Sperm chromatin was prepared as in Figure 6B (molar ratio SpOrc4/XlOrc2 = 3.7). Individual aliquots were then eluted with the indicated amount of KCl in Buffer A, which contained 50 µM ATP to stabilize ORC–DNA binding. Each eluate was assayed for SpOrc4. Elution of chromatin-bound SpOrc4 required 0.5–0.6 M KCl (Figure 7A), consistent with the fact that at least 0.5 M salt is required to release SpOrc4 either from S.pombe chromatin (Moon et al., 1999), or from chromatin in insect cells in which SpOrc4 was overexpressed (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001). This was the same KCl concentration required to elute SpOrc4 from either poly(dA-dT)·poly(dT-dA) [AT/TA], or poly(dA)·poly(dT) [AA/TT] bound to cellulose. In this case, the protein was eluted sequentially with the indicated concentrations of KCl in Buffer A (Figure 7A; Table I). SpOrc4 was eluted from AA/TT at 0.6–0.7 M KCl (peak at 0.63 M) and from AT/TA at 0.5–0.6 M KCl (peak at 0.5 M). In contrast, SpOrc4 was eluted from poly(dG-dC)·poly(dC-dG) [GC/CG] at 0.22–0.28 M KCl (peak at 0.27 M). Therefore, all of the chromatin-bound SpOrc4 was located at AT-rich sequences.

Fig. 7. SpOrc4 and XlORC bound preferentially to asymmetric A:T-sequences. (A) Xenopus egg extract supplemented with SpOrc4 at a molar ratio with XlOrc2 of 3.7 (Figure 6) was incubated with sperm chromatin for 10 min. The reaction was divided into eight portions. Chromatin was isolated from each fraction by sedimentation and eluted with the indicated amount of KCl. For comparison, purified SpOrc4 was adsorbed to the indicated DNA resin in 40 mM KCl, and then eluted sequentially with one column volume Buffer A containing the indicated concentration of KCl. Aliquots of each fraction (including the original sample) were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted for the indicated protein. AA/TT is poly(dA)·poly(dT) cellulose. AT/TA is poly(dA-dT)·poly(dT-dA) cellulose. GC/CG is poly(dG-dC)·poly(dC- dG) cellulose. (B) Cdc6-depleted Xenopus egg extract was incubated with sperm chromatin for 10 min, and the proteins eluted sequentially with the indicated KCl concentration. Fractions of XlOrc2 eluted with low salt concentrations (a) and with high salt concentrations (b) are indicated. For comparison, complete Xenopus egg extract was diluted with Buffer A, adsorbed to the indicated DNA resin, and analyzed as in (A). Proteins were identified by their size and immunospecificity. In XlCdc6 assays, the upper band was XlOrc2 and the lower was XlCdc6. The two antibodies were applied sequentially to the same membrane.

Table I. Preferential binding of replication initiation proteins to DNA.

| Protein | % bound |

KCl peak elution (M) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA/TT | AT/TA | CG/CG | AA/TT | AT/TA | CG/CG | |

| SpOrc4 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.27 |

| XlOrc2 | 76 | 48 | 47 | 0.15, 0.28a | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| XlCdc6 | 47 | 29 | 31 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| XlMcm3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0.12 | – | – |

The fraction of each protein bound was calculated from the amount of protein in each aliquot and the total volume of the sample or eluted fraction. Unbound XlOrc2, XlCdc6 and XlMcm3 were in the flow-through; no proteins were recovered in the highest salt fractions.

aXlOrc2 eluted over a broad salt concentration consistent with two peaks, one at 0.15 M KCl (fractions 0.10–0.19 M KCl) and one at 0.28 M KCl (fractions 0.22–0.31 M KCl).

Xenopus ORC preferentially binds asymmetric A:T-rich sequences

Previous studies have suggested that pre-RC assembly affects the affinity of XlORC for sperm chromatin (Rowles et al., 1999). Therefore, to determine whether or not XlORC preferentially bound to AT-rich sequences in sperm chromatin, XlCdc6-depleted egg extract was incubated for 10 min with sperm chromatin in the absence of SpOrc4, and then chromatin-bound XlORC was eluted with sequential increases of KCl in Buffer A. About half of the bound XlOrc2 was released from 0.1–0.19 M KCl (Figure 7B, a) and the remainder with 0.22–0.37 M KCl (Figure 7B, b). The same result was obtained with complete Xenopus egg extract (data not shown). This salt elution profile was remarkably similar to that obtained with XlORC bound to AA/TT resin.

Xenopus egg extract (diluted in Buffer A) was passed over either GC/CG or AT/TA or AA/TT resins and the resin was then sequentially eluted with the indicated amount of KCl in Buffer A. The affinity of XlOrc2 for each duplex homopolymer was determined by the amount bound, and by the salt concentration required to elute it. About 76% of the XlOrc2 in egg extract bound to AA/TT, and the bulk of it was eluted at 0.1–0.31 M KCl, with some ORC eluted at salt concentrations up to 0.5 M KCl (Figure 7B; Table I). About 48% of the XlOrc2 in egg extract was bound to GC/CG or AT/TA, and the bulk of it was eluted with 0.1–0.19 M KCl. Therefore, although XlORC had a lower affinity for DNA than did SpOrc4, ∼40% of the XlORC preferentially bound with higher affinity to AA/TT than to either AT/TA or GC/CG (Figure 7B, fractions 0.22–0.31 M KCl).

XlCdc6 and XlMcm3 proteins were also bound to these resins, and they bound preferentially to the asymmetric A:T-sequence. About 47% of the XlCdc6 in egg extract was adsorbed to AA/TT, and was eluted with 0.15 M KCl (Figure 7B). In contrast, ∼30% bound to AT/TA or CG/GC and was eluted at 0.11 M salt. Remarkably, ∼10% of the total Mcm3 in the extract bound to AA/TT, while only 3% bound either to AT/TA or to GC/CG, suggesting that pre-RC assembly occurred more efficiently on asymmetric A:T-sequences. The concentration of Mcm proteins in Xenopus egg extracts (∼1 µM; Mahbubani et al., 1997) is 10 times greater than either ORC (50–110 nM; Carpenter et al., 1996; Rowles et al., 1996; Carpenter and Dunphy, 1998; Tugal et al., 1998) or Cdc6 (80 nM; Coleman et al., 1996). Therefore, based on the fraction of protein bound (Table I), each ORC–Cdc6 protein complex appears to recruit one Mcm3 molecule to AT/TA or GC/CG resins, but two Mcm3 molecules to AA/TT resins. These results confirmed that the DNA-bound XlORC in this experiment was capable of initiating assembly of pre-RCs, and suggested that pre-RC assembly at asymmetric A:T-rich sequences was more efficient than at either alternating AT or GC-rich sequences.

Discussion

Origin recognition proteins are structurally conserved throughout evolution (Bogan et al., 2000; Bell, 2002), implying that their biochemical properties and their mechanism of action are essentially the same from one species to another. However, there are striking incongruities. For example, SpOrc4 is unique among ORC proteins in that its N-terminus has been extended and designed to bind strongly and specifically to AT-rich sequences without a dependency on ATP. Moreover, some eukaryotic cells, such as budding and fission yeast, initiate DNA replication at specific DNA sites, while others, such as Xenopus and Drosophila embryos, appear to initiate DNA replication at non-specific sites. The results presented here reveal that eukaryotic ORCs are, in fact, functionally, if not structurally, conserved, and preferentially bind to the same AT-rich sequences.

The same ORC subunits that bind and hydrolyze ATP in budding yeast and flies, also bind and hydrolyze ATP in fission yeast. Thus, a prediction based on analysis of protein sequences was confirmed by biochemical assays. Moreover, this result not only confirmed expectations based on sequence analysis, but illuminated the role of ATP in the initiation process. Fission yeast, in contrast to budding yeast, does not require ATP for binding to specific DNA sites, suggesting that ATP is not required for DNA binding, per se, but for organization of a functional ORC/chromatin site. In fission yeast, only the Orc4 subunit is required for site-specific DNA binding, whereas in budding yeast, ORC subunits 1–5 are required, and ATP may stabilize this complex.

Under conditions that permit initiation of DNA replication in vitro, frog ORC preferentially binds to and initiates DNA replication at the same, or similar, DNA sites used in fission yeast. The fact that XlORC can also utilize other DNA sequences and that Xenopus eggs contain a great excess of ORC has historically masked the functional similarity between XlORC and ORCs from other species. The fact that nature has uniquely designed the SpOrc4 protein to target specific asymmetric AT-rich sequences suggests that the same or similar sequences constitute an essential component of many, if not all, eukaryotic replication origins. We suggest that most, perhaps all, ORCs preferentially target asymmetric A:T-rich sequences, but that the actual binding may be affected by epigenetic parameters (DePamphilis, 1999). Therefore, the extent of origin specificity will vary with animal development and cell differentiation.

ATP binding and hydrolysis by SpORC

While the importance of ATP binding and hydrolysis to site-specific DNA binding by ORC was established with S.cerevisiae Orc1, the role of ATP binding and hydrolysis in Orc5 and potentially in Orc4 remained to be elucidated (Bell, 2002; Bell and Dutta, 2002). Here we show that SpOrc1, 4 and 5 proteins bind ATP (Figure 1) and exhibit ATPase activity (Figures 2 and 3). The reduced affinity of SpOrc5 for ATP reflects the fact that the Walker A motif in SpOrc5 (GXXXXAKT) differs significantly from the Walker A consensus sequence (GXXGXGKT). Similarly, the reason that SpOrc4 binds ATP tightly (Figure 1B) while ScOrc4 does not (Klemm et al., 1997) is that SpOrc4 has both Walker A and B motifs, whereas ScOrc4 lacks the Walker A motif. These results, together with those from S.cerevisiae (Klemm et al., 1997) and D.melanogaster (Chesnokov et al., 2001), confirm the prediction from protein sequence analysis (Neuwald et al., 1999) that all Orc1, Orc4 and Orc5 subunits will bind ATP.

Although ATPase activity in SpORC was low compared with ScORC and DmORC, it appeared to be indigenous to specific SpORC subunits. The ratio of ATPase activity to SpOrc1 and SpOrc5 protein in the ORC-5 complex was nearly constant (Figure 2C), and S.pombe replication origin DNA specifically reduced SpOrc4 ATPase activity ∼2-fold (Figure 2D), consistent with reports that DmORC ATPase activity is reduced ∼2-fold by Drosophila-origin DNA (Chesnokov et al., 2001), and ScORC ATPase activity is reduced ∼8-fold by S.cerevisiae-origin DNA (Klemm and Bell, 2001). These results suggest that the conformation of the C-terminal half of SpOrc4, in which the Walker A and B motifs are located, is altered when SpOrc4 binds to replication origins. ATP may contribute either to stabilization of ORC at replication origins, or to assembly of a pre-RC, as previously suggested for S.cerevisiae (Klemm and Bell, 2001).

XlORC initiates DNA replication preferentially at sequences targeted in S.pombe

Competition studies between SpOrc4 and XlORC, together with DNA affinity studies on these proteins, revealed that XlORC preferentially initiated DNA replication at the same sites targeted by SpOrc4. SpOrc4, either alone or in the company of the ORC-5 complex, did not initiate DNA replication in an egg extract depleted of XlORC proteins, suggesting that SpORC cannot initiate pre-RC assembly using Xenopus proteins. Therefore, binding of SpOrc4 to chromatin would be non-productive, and it would inhibit XlORC from initiating DNA replication at those DNA-binding sites selected by SpOrc4. In fact, this has proved to be the case.

Up to 70% of the XlORC-dependent DNA replication was inhibited by SpOrc4 (Figure 3A and B), and this inhibition resulted from competition between SpOrc4 and XlORC for the same or similar DNA-binding sites in chromatin. Inhibition by SpOrc4 did not result either from replacement of the XlOrc4 subunit by SpOrc4 (Figure 3D), or from disruption of Xenopus pre-RCs (Figure 4B), or from inhibition of DNA synthesis at replication forks (Figure 4A). In fact, several different experiments demonstrated that inhibition by SpOrc4 resulted from binding of SpOrc4 to AT-rich sites in sperm chromatin. (i) Binding of SpOrc4 to chromatin was required for inhibition of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts, because the C-terminal half of SpOrc4, which lacks the AT-hook motifs, was unable to bind to DNA (Figure 6C) and did not inhibit DNA synthesis (Figure 5). (ii) Inhibition required binding to particular sequences, because MmTead2, which binds to sequences different from those selected by SpOrc4, did not inhibit DNA synthesis (Figure 5). (iii) The amount of chromatin-bound XlORC decreased as the amount of chromatin-bound SpOrc4 increased. For example, at a molar ratio of SpOrc4 to XlORC of 7.4, the amount of chromatin-bound XlORC was reduced by 70% (Figure 6B), in agreement with the fact that ∼70% of DNA replication was inhibited under this condition (Figure 3C). As expected, the amount of pre-RCs (i.e. XlOrc2, XlCdc6, XlMcm3 and XlCdc7) decreased proportionally (Figure 6B), because pre-RC assembly depends on ORC binding to chromatin. (iv) SpOrc4 bound exclusively to AT-rich sequences in sperm chromatin (Figure 7A). Under these conditions, SpOrc4 inhibited both XlORC-dependent DNA replication and XlORC binding to chromatin by ∼70%. Therefore, XlORC preferentially initiated DNA replication in egg extracts by binding to the same AT-rich sequences targeted by S.pombe ORC. (v) DNA cellulose chromatography revealed that ∼40% of XlORC bound to asymmetric A:T-rich sequences with greater affinity than to either AT- or GC-rich sequences (Figure 7B). The salt elution profile for release of XlORC that bound to sperm chromatin was remarkably similar (Figure 7B), suggesting that a similar fraction of XlORC preferentially bound to asymmetric A:T-rich sequences when initiating replication in egg extract. Moreover, Cdc6 and Mcm proteins were also loaded preferentially onto asymmetric A:T-sequence (Figure 7B; Table I). If the remaining 60% XlORC bound DNA randomly, then half of it would bind to AT-rich sequences, resulting in a total of 70% XlORC bound to AT-rich sequences and 30% to GC-rich sequences. Thus, a significant fraction of XlORC in egg extract selectively bound to sequences preferred by SpOrc4. Taken together, these results reveal that Xenopus initiates DNA replication preferentially at the same or similar sequences to those targeted in S.pombe.

Site-specific initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells

The results presented here, the DNA-binding properties of ORCs from yeast and flies, and the characteristics of replication origins in yeast, flies and mammals (see Introduction) all suggest that most, perhaps all, eukaryotic ORCs preferentially bind to the same or similar AT-rich sequences. In addition, DNA-binding specificity will be affected by at least two parameters: the ratio of ORC to DNA, and the presence of ORC-associated proteins. A high ratio of ORC/DNA would allow initiation to occur at many DNA sites, regardless of their affinity for ORC, whereas a low ratio of ORC/DNA would favor initiation sites with the greatest affinity for ORC. This could explain why site-specific initiation of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts was not detected, because Xenopus eggs contain 50–110 nM ORC, or ∼105 more ORC molecules than in one somatic cell (Carpenter et al., 1996; Rowles et al., 1996; Carpenter and Dunphy, 1998; Tugal et al., 1998). In addition, a significant population of XlORC can bind to GC-rich sequences, thus masking the presence of site-specific initiation events. This could also explain why site-specific ORC-dependent DNA replication has not yet been observed in soluble extracts of S.cerevisiae or S.pombe, two systems where ORC has been shown to bind specifically to ARS elements in vitro. For example, S.cerevisiae contains about two ORCs per replication origin or one ORC per 24 kb DNA [∼600 ORC molecules per cell (Rowley et al., 1995); ∼332 replication origins (Raghuraman et al., 2001)], a condition that is difficult to reproduce in vitro and still detect DNA replication events.

Association of ORC with other proteins may facilitate its binding to specific chromosomal sites. Examples of this mechanism are the EBNA-1-binding sites at the Epstein–Barr virus replication origin (Chaudhuri et al., 2001; Dhar et al., 2001; Schepers et al., 2001), and the E2F and c-myb binding sites at D.melanogaster replication origins (Bosco et al., 2001; Beall et al., 2002). The fact that about half of the XlORC bound more tightly to AA/TT DNA sequences than to either alternating AT or alternating GC sequences (Figure 7), suggested the presence of at least two forms of ORC–DNA complexes. This could result either from a heterogeneous population of ORCs, or from the presence of other proteins in the extract that modify the binding of ORC to DNA. ORC heterogeneity could result either from post-translational modifications of individual subunits, or from differences in ORC organization. Given the stringent competition between XlORC and SpOrc4 for DNA-binding sites, we suggest that a DNA-binding protein containing several AT-hook motifs associates with XlORC and targets it to asymmetric A:T-rich sequences. The N-terminal domain of SpOrc4 may have been an auxiliary protein that evolution covalently attached to the SpOrc4 subunit.

Materials and methods

Proteins and antibodies

Schizosaccharomyces pombe Orc4 protein and a complex consisting of S.pombe Orc1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 (ORC-5 complex) were purified (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001). The C-terminal half of SpOrc4 protein (SpOrc4-C) (aa515–aa972) was cloned into BamHI site of pET30a (Novegen), expressed and purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The His6- and T-epitope tags, which were used to facilitate protein purification, were subsequently removed with enterokinase. Xenopus FLAG-tagged Orc2 and mouse Tead-2 (Vassilev et al., 2001) proteins were provided by Xiaohong Zhang and Alex Vassilev. Cdc6, Cdc7 and Mcm3 antisera were prepared as described (Frolova et al., 2002).

Crosslinking of ATP to proteins

A 10 µl reaction containing 50 mM HEPES–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 0.04% NP-40, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 µl [α-32P]ATP and 50 ng of either SpOrc4p or the ORC-5 complex was irradiated for 5 min in a UV Stratolinker (340 nm) to crosslink ATP to protein. The mixture was then subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and 32P-labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography.

ATPase assay

ATPase activity was measured at 30°C for from 15–90 min in 30 µl containing 1 µl [γ-32P]ATP (10 mCi/ml, 6000 Ci/mmol, Amersham), 50 mM HEPES–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), and either SpOrc4 or ORC-5 proteins. 32Pi was separated from [γ-32P]ATP by ascending chromatography on polyethyleneimine–cellulose thin-layer plates in 1 M formic acid and 0.4 M LiCl. Autoradiographic data were quantified by densitometry using NIH image analysis.

DNA synthesis assay

Sperm chromatin (Smythe and Newport, 1991) and Xenopus egg extract (Chong et al., 1997) were prepared as described, with modifications (Li et al., 2000). Where indicated, egg extract was depleted of >98% of XlOrc2 (Li et al., 2000) or >98% of XlCdc6 (Sun et al., 2002). Egg extracts were supplemented with 25 mM phosphocreatine, 30 µg/ml creatine phosphokinase and 250 µg/ml cycloheximide, and then activated by 0.3 mM CaCl2 for 30 min just prior to use. DNA synthesis was measured by incubating 15 µl reactions containing 9 µl ORC-depleted Xenopus egg extract, 1 µl whole egg extract, 100 ng sperm chromatin DNA, 1 µl [α-32P]dCTP (10 mCi/ml, 6000 Ci/mmol, Amersham) at 22°C for the times indicated. At certain times either SpOrc4, SpOrc4-C or MmTead2 protein was added at the concentrations indicated. DNA synthesis was arrested by diluting aliquots into a 10-fold excess of 0.5% SDS, 50 mM EDTA and 50 µg/ml proteinase K. Samples were incubated overnight at room temperature before spotting aliquots on 2.5 cm DE81 discs (VWR). Discs were dried for 30 min at room temperature, washed four times in 0.3 M ammonium formate (pH 8.0) to elute unincorporated nucleotides and once with 95% ethanol to remove water. Discs were dried and the radioactivity measured by scintillation counting.

Protein chromatin-binding assay

DNA synthesis assays were increased 3-fold in size, incubated at 22°C for 20 min, and then diluted with 5 volumes of modified nuclear isolation buffer (NIB-A) (50 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.6, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.15 mM spermine, 1 mM ATP, 2 mM DTT, and 1 µg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin), and centrifuged (6000 g, 10 min, 4°C) through 0.7 ml of 15% sucrose in NIB-A (NIB-A-Su). The pellet was gently and quickly resuspended in 200 µl NIB-A plus 0.1% Triton X-100. Chromatin was again centrifuged through NIB-A-Su (16 000 g, 3 min, 4°C), resuspended in SDS–PAGE loading buffer, subjected to SDS–PAGE, and proteins detected by immunoblotting using appropriate antibodies (Sun et al., 2002). The second washing was critical to see protein-binding specificity.

DNA affinity chromatography

Poly(dA)·poly(dT), poly(dA-dT)·poly(dT-dA), and poly(dG-dC)· poly(dC-dG) (Amersham) were bound individually to cellulose (Alberts and Herrick, 1971). Chromatography was carried out at 4°C in Eppendorf pipette tips (1 ml) containing 0.25 ml of the indicated DNA resin equilibrated with 20 column volumes of Buffer A (50 mM HEPES–HCl pH 7.5, 40 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 0.04% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.05 mM ATP, 1 µg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin and pepstatin). Activated Xenopus egg extract (200 µl) was diluted 3-fold with Buffer A and then centrifuged (16 000 g, 10 min, 4°C) to remove membranes and particles. Extract passed through the resin at 1.5 ml/h and the column was then washed with 10 column volumes of Buffer A. Alternatively, 5 µg SpOrc4 in 200 µl Buffer A was applied. Proteins were eluted in steps of 0.25 ml Buffer A containing the indicated concentration of KCl at 1.5 ml/h. Aliquots from each fraction were subjected to SDS–PAGE electrophoresis and immunoblotting with the indicated antibody.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Xiaohong Zhang and Alex Vassilev for providing Xenopus FLAG-tagged Orc2 and mouse Tead-2 proteins.

References

- Abdurashidova G., Deganuto,M., Klima,R., Riva,S., Biamonti,G., Giacca,M. and Falaschi,A. (2000) Start sites of bidirectional DNA synthesis at the human lamin B2 origin. Science, 287, 2023–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B. and Herrick,G. (1971) DNA cellulose chromatography. Methods Enzymol., 21, 198–217. [Google Scholar]

- Altman A.L. and Fanning,E. (2001) The Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase replication origin beta is active at multiple ectopic chromosomal locations and requires specific DNA sequence elements for activity. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 1098–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin R.J., Orr-Weaver,T.L. and Bell,S.P. (1999) Drosophila ORC specifically binds to ACE3, an origin of DNA replication control element. Genes Dev., 13, 2639–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall E.L., Manak,J.R., Zhou,S., Bell,M., Lipsick,J.S. and Botchan,M.R. (2002) Role for a Drosophila Myb-containing protein complex in site-specific DNA replication. Nature, 420, 833–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S.P. (2002) The origin recognition complex: from simple origins to complex functions. Genes Dev., 16, 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S.P. and Dutta,A. (2002) DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 71, 333–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielinsky A.K., Blitzblau,H., Beall,E.L., Ezrokhi,M., Smith,H.S., Botchan,M.R. and Gerbi,S.A. (2001) Origin recognition complex binding to a metazoan replication origin. Curr. Biol., 11, 1427–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow J.J., Gillespie,P.J., Francis,D. and Jackson,D.A. (2001) Replication origins in Xenopus egg extract are 5–15 kilobases apart and are activated in clusters that fire at different times. J. Cell Biol., 152, 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan J.A., Natale,D.A. and DePamphilis,M.L. (2000) Initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication: conservative or liberal? J. Cell Physiol., 184, 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco G., Du,W. and Orr-Weaver,T.L. (2001) DNA replication control through interaction of E2F-RB and the origin recognition complex. Nat. Cell Biol., 3, 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter P.B. and Dunphy,W.G. (1998) Identification of a novel 81-kDa component of the Xenopus origin recognition complex. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 24891–24897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter P.B., Mueller,P.R. and Dunphy,W.G. (1996) Role for a Xenopus Orc2-related protein in controlling DNA replication. Nature, 379, 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri B., Xu,H., Todorov,I., Dutta,A. and Yates,J.L. (2001) Human DNA replication initiation factors, ORC and MCM, associate with oriP of Epstein–Barr virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 10085–10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnokov I., Remus,D. and Botchan,M. (2001) Functional analysis of mutant and wild-type Drosophila origin recognition complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 11997–12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong J.P., Thommes,P., Rowles,A., Mahbubani,H.M. and Blow,J.J. (1997) Characterization of the Xenopus replication licensing system. Methods Enzymol., 283, 549–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang R.Y. and Kelly,T.J. (1999) The fission yeast homologue of Orc4p binds to replication origin DNA via multiple AT-hooks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 2656–2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman T.R., Carpenter,P.B. and Dunphy,W.G. (1996) The Xenopus Cdc6 protein is essential for the initiation of a single round of DNA replication in cell-free extracts. Cell, 87, 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePamphilis M.L. (1999) Replication origins in metazoan chromosomes: fact or fiction? BioEssays, 21, 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S.K., Yoshida,K., Machida,Y., Khaira,P., Chaudhuri,B., Wohlschlegel,J.A., Leffak,M., Yates,J. and Dutta,A. (2001) Replication from oriP of Epstein–Barr virus requires human ORC and is inhibited by geminin. Cell, 106, 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolova N.S., Schek,N., Tikhmyanova,N. and Coleman,T.R. (2002) Xenopus Cdc6 performs separate functions in initiating DNA replication. Mol. Biol. Cell, 13, 1298–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M. and Antequera,F. (1999) Organization of DNA replication origins in the fission yeast genome. EMBO J., 18, 5683–5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E. and Lane,D. (1999) Using Antibodies: a Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Hyrien O., Maric,C. and Mechali,M. (1995) Transition in specification of embryonic metazoan DNA replication origins. Science, 270, 994–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ina S., Sasaki,T., Yokota,Y. and Shinomiya,T. (2001) A broad replication origin of Drosophila melanogaster, oriDalpha, consists of AT-rich multiple discrete initiation sites. Chromosoma, 109, 551–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.W., Desai,D., Khan,S. and Eberhardt,N.L. (2000) Cooperative binding of TEF-1 to repeated GGAATG-related consensus elements with restricted spatial separation and orientation. DNA Cell Biol., 19, 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko K.J. and DePamphilis,M.L. (1998) Regulation of gene expression at the beginning of mammalian development and the TEAD family of transcription factors. Dev. Genet., 22, 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C., Ladenburger,E.M., Kremer,M. and Knippers,R. (2002) The origin recognition complex marks a replication origin in the human TOP1 gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 31430–31440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.M. and Huberman,J.A. (1998) Multiple orientation-dependent, synergistically interacting, similar domains in the ribosomal DNA replication origin of the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 7294–7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.M. and Huberman,J.A. (1999) Influence of a replication enhancer on the hierarchy of origin efficiencies within a cluster of DNA replication origins. J. Mol. Biol., 288, 867–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm R.D. and Bell,S.P. (2001) ATP bound to the origin recognition complex is important for preRC formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 8361–8367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm R.D., Austin,R.J. and Bell,S.P. (1997) Coordinate binding of ATP and origin DNA regulates the ATPase activity of the origin recognition complex. Cell, 88, 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D. and DePamphilis,M.L. (2001) Site-specific DNA binding of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe origin recognition complex is determined by the Orc4 subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 8095–8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D. and DePamphilis,M.L. (2002) Site-specific ORC binding, pre-replication complex assembly and DNA synthesis at Schizosaccharomyces pombe replication origins. EMBO J., 21, 5567–5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenburger E.M., Keller,C. and Knippers,R. (2002) Identification of a binding region for human origin recognition complex proteins 1 and 2 that coincides with an origin of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 1036–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.G. and Bell,S.P. (1997) Architecture of the yeast origin recognition complex bound to origins of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 7159–7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.K., Moon,K.Y., Jiang,Y. and Hurwitz,J. (2001) The Schizosaccharomyces pombe origin recognition complex interacts with multiple AT-rich regions of the replication origin DNA by means of the AT-hook domains of the spOrc4 protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 13589–13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.J., Bogan,J.A., Natale,D.A. and DePamphilis,M.L. (2000) Selective activation of pre-replication complexes in vitro at specific sites in mammalian nuclei. J. Cell Sci., 113, 887–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Zhang,H. and Tower,J. (2001) Functionally distinct, sequence-specific replicator and origin elements are required for Drosophila chorion gene amplification. Genes Dev., 15, 134–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahbubani H.M., Chong,J.P., Chevalier,S., Thommes,P. and Blow,J.J. (1997) Cell cycle regulation of the replication licensing system: involvement of a Cdk-dependent inhibitor. J. Cell Biol., 136, 125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon K.Y., Kong,D., Lee,J.K., Raychaudhuri,S. and Hurwitz,J. (1999) Identification and reconstitution of the origin recognition complex from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 12367–12372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwald A.F., Aravind,L., Spouge,J.L. and Koonin,E.V. (1999) AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res., 9, 27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno Y., Satoh,H., Sekiguchi,M. and Masukata,H. (1999) Clustered adenine/thymine stretches are essential for function of a fission yeast replication origin. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 6699–6709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman M.K. et al. (2001) Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science, 294, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanowski P., Madine,M.A., Rowles,A., Blow,J.J. and Laskey,R.A. (1996) The Xenopus origin recognition complex is essential for DNA replication and MCM binding to chromatin. Curr. Biol., 6, 1416–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles A., Chong,J.P., Brown,L., Howell,M., Evan,G.I. and Blow,J.J. (1996) Interaction between the origin recognition complex and the replication licensing system in Xenopus. Cell, 87, 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles A., Tada,S. and Blow,J.J. (1999) Changes in association of the Xenopus origin recognition complex with chromatin on licensing of replication origins. J. Cell Sci., 112, 2011–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley A., Cocker,J.H., Harwood,J. and Diffley,J.F. (1995) Initiation complex assembly at budding yeast replication origins begins with the recognition of a bipartite sequence by limiting amounts of the initiator, ORC. EMBO J., 14, 2631–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers A., Ritzi,M., Bousset,K., Kremmer,E., Yates,J.L., Harwood,J., Diffley,J.F. and Hammerschmidt,W. (2001) Human origin recognition complex binds to the region of the latent origin of DNA replication of Epstein–Barr virus. EMBO J., 20, 4588–4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe C. and Newport,J.W. (1991) Systems for the study of nuclear assembly, DNA replication and nuclear breakdown in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. Methods Cell Biol., 35, 449–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W.H., Coleman,T.R. and DePamphilis,M.L. (2002) Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the association between origin recognition proteins and somatic cell chromatin. EMBO J., 21, 1437–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. and Masukata,H. (2001) Interaction of fission yeast ORC with essential adenine/thymine stretches in replication origins. Genes Cells, 6, 837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Ohara,E., Nishitani,H. and Masukata,H. (2003) Multiple ORC-binding sites are required for efficient MCM loading and origin firing in fission yeast. EMBO J., 22, 964–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugal T., Zou-Yang,X.H., Gavin,K., Pappin,D., Canas,B., Kobayashi,R., Hunt,T. and Stillman,B. (1998) The Orc4p and Orc5p subunits of the Xenopus and human origin recognition complex are related to Orc1p and Cdc6p. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 32421–32429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev A., Kaneko,K.J., Shu,H., Zhao,Y. and DePamphilis,M.L. (2001) TEAD/TEF transcription factors utilize the activation domain of YAP65, a Src/Yes-associated protein localized in the cytoplasm. Genes Dev., 15, 1229–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J., Sun,L. and Newport,J. (1998) Regulated chromosomal DNA replication in the absence of a nucleus. Mol. Cell, 1, 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]