Abstract

In plants, expression of a disease-resistance character following perception of a pathogen involves massive deployment of transcription-dependent defenses. Thus, if rapid and effective defense responses have to be achieved, it is crucial that the pathogenic signal is transduced and amplified through pre-existing signaling pathways. Reversible phosphorylation of specific transcription factors, by a concerted action of protein kinases and phosphatases, may represent a mechanism for rapid and flexible regulation of selective gene expression by environmental stimuli. Here we identified a novel DNA-binding protein from tobacco plants, designated DBP1, with protein phosphatase activity, which binds in a sequence-specific manner to a cis- acting element of a defense-related gene and participates in its transcriptional regulation. This finding helps delineate a terminal event in a signaling pathway for the selective activation of early transcription-dependent defense responses in plants, and suggests that stimulus-dependent reversible phosphorylation of regulatory proteins may occur directly in a transcription protein–DNA complex.

Keywords: CEVI1/DBP1/plant defense signaling/PP2C/transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Upon pathogen attack, plants activate an array of inducible responses that lead to the local and systemic expression of a broad spectrum of antimicrobial defenses. During the last years, much progress has been achieved towards understanding the mechanisms by which plants detect and defend against microbial attack. This understanding has been facilitated by the cloning and characterization of plant disease-resistance factors that recognize the corresponding avirulent factors from the pathogen to trigger the so-called hypersensitive reaction (HR) (Dangl and Jones, 2001), a cell-death program directed to confining the invading pathogen and preventing spread of the infection (Agrios, 1988). The onset of HR in turn results in activation of systemic acquired resistance (SAR; Ross, 1961), another well characterized defense response that provides long-lasting protection throughout the plant against a broad spectrum of pathogens (Ryals et al., 1996). The identification of plant cell components involved in signal transduction (Glazebrook, 2001), and of endogenous plant defense signal molecules, including salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) (Dong, 1998; Kunkel and Brooks, 2002), has also been of paramount importance for understanding the coupling of pathogen recognition to the activation of defense responses in the plant.

The expression of the defense-related CEVI1 gene from tomato plants, and its homologue from tobacco, has been shown to be induced during the course of compatible plant–virus interactions, but not during incompatible interactions, and also when leaves are detached from healthy plants (Mayda et al., 2000a). This induced expression of CEVI1 was observed to be independent of signal molecules mediating plant defense responses, such as SA, ET or JA (Mayda et al., 2000a). Furthermore, phenotypic and molecular characterization of Arabidopsis dth mutants, compromised in the transcriptional control of the CEVI1 gene, suggests that priming of insensitivity to the plant hormone auxin may be on the basis of the mechanisms controlling expression of this gene. In fact, detailed analysis of these mutants, and in particular of dth9, has revealed that keeping intact auxin perception in the plant is pivotal to mount a proper and effective defense response (Mayda et al., 2000b).

Delineation of the cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors underlying the activation of pathogen-induced genes in plants provides the basis for characterizing the terminal stages of signal transduction pathways involved in the deployment of transcription-dependent defenses. In the few last years, cis-acting elements and minimal promoter regions conferring responsiveness to elicitors and to plant signal molecules involved in defense, e.g. ET, SA or JA, have been identified, and in some cases, their cognate trans-acting factors isolated (Rushton and Somssich, 1998). Post-translational modification via protein phosphorylation appears to be the principal mechanism for rapid modulation of transcription factor activity or localization in response to extracellular signals, and thus plays a major role in signal transduction pathways. This modulation is accomplished by the coordinated activity of protein kinases and phosphatases. Most of these phosphorylation events occur on serine and threonine residues of the target proteins. Originally considered to act merely by reversing the effects of protein kinases, in the last few years it has become evident that protein phosphatases fulfil essential regulatory functions. Monomeric serine/threonine protein phosphatases that are Mg2+-dependent belong to the PP2C class (Shenolikar, 1994; Wera and Hemmings, 1995). Biochemical and genetic studies have recently implicated PP2Cs as negative modulators of stress-responsive signaling pathways in animals, yeast and also in plants (Maeda et al., 1994; Sheen, 1996; Gaits et al., 1997; Takekawa et al., 1998; Gosti et al., 1999; Merlot et al., 2001).

Towards the elucidation of the molecular mechanism underlying the transcriptional control of the CEVI1 gene, here we report the identification of a cis-acting element in the 5′ promoter region of this gene that functions as a target sequence for a detachment and pathogen-sensitive DNA–protein complex. We also report the isolation of a cDNA encoding a novel DNA-binding protein phosphatase (DBP1), which specifically binds to that element and contributes to the transcriptional regulation of CEVI1 gene expression.

Results

Functional analysis of the CEVI1 promoter

Previous inspection of the 5′ promoter region of the CEVI1 gene in search for conserved motifs (Mayda et al., 2000a) revealed twice the presence of a TGTCTC motif, core sequence of auxin-response elements (AuxRE) (Ulmasov et al., 1995), at positions –959 to –954, and –119 to –114, respectively. In addition, an inverted GCC-box (–138 to –132), which has been found to mediate ET-inducible gene expression (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995), and an H-box-like sequence (–681 to –665), similar to that conserved in some genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Loake et al., 1992), were also identified in the CEVI1 gene promoter region.

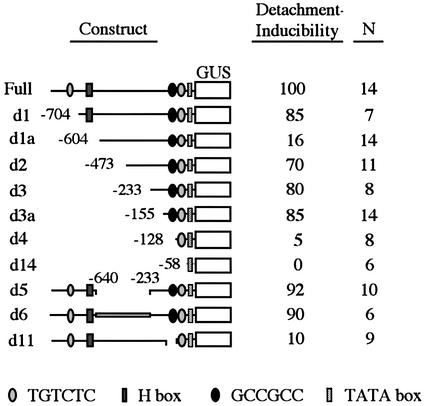

As a first step in defining the DNA sequence elements that may be important in mediating induction of CEVI1 gene expression, a series of promoter deletion mutants was created. The original 1267 bp full-length promoter (Mayda et al., 2000a) was modified as described in Materials and methods and the resulting β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter constructs introduced into tobacco by Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation. Detection of GUS activity was achieved both fluorimetrically in leaf extracts and by in situ GUS staining of leaf samples from these transgenic plants, before and after floating leaf discs in buffer solution for 24 h. Through a series of 5′ unidirectional deletions shown in Figure 1, we observed that 155 bp of promoter sequence (construct d3a) was sufficient to maintain major responsiveness to detachment, while 128 bp of promoter sequence (construct d4) did not show inducibility. Additionally, construct d1a showed <20% of the induced reporter gene expression achieved with the full-length promoter, suggesting the presence of a negative element in this region (between positions –604 and –473), whose effect is somehow negated by the presence of sequences (including the H-box) located upstream (up to –704; construct d1). These could represent elements modulating specific aspects of the promoter in vivo. The upstream AuxRE-like element (at position –959 to –954) seems accessory, since its deletion very weakly affects the inducibility of the reporter gene. Furthermore, an internal deletion in the CEVI1 promoter (between positions –640 and –233; construct d5), or the replacement of this region with an exogenous DNA sequence of similar length (construct d6) did not affect inducibility. Conversely, when a shorter internal deletion (from –155 to –128; construct d11) was introduced in the context of the full-length promoter, inducibility was drastically reduced. Taken together, these results indicate that sequence elements lying around or between positions –155 and –128 are pivotal for CEVI1 gene induction.

Fig. 1. Functional analysis of the CEVI1 promoter. A series of unidirectional and internal deletions of the CEVI1 promoter were transcriptionally fused to the GUS reporter gene and used to generate transgenic tobacco plants. The position of known cis-acting elements is shown as indicated in the bottom legend. Constitutive and detachment-inducible reporter gene expression was analyzed in these plants. (+/–) symbols denote detection/absence of constitutive GUS expression in nodes. Figures represent average estimates of GUS activity after detachment as a percentage relative to the full promoter construct. N, number of independent transgenic lines analyzed for each construct.

Identification of a specific protein binding site in the CEVI1 promoter

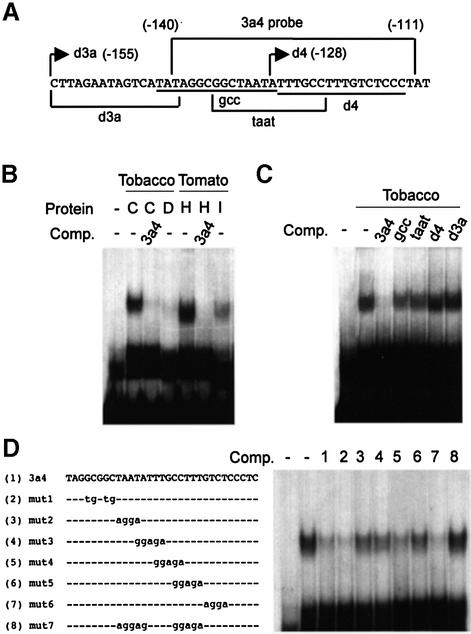

The functional analysis in transgenic tobacco plants revealed that the observed cis-acting elements responsible for inducibility of the CEVI1 promoter must be located either completely or at least partly between positions –155 and –128. As mentioned above, two well-characterized cis-acting elements lie in this region of the promoter: an inverted GCC-box, which has been found to mediate ET-inducible expression of pathogenesis-related genes, and a TGTCTC element, shown to confer auxin inducibility (Figure 2A). To test any potential protein–DNA interaction within this promoter region, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) with protein extracts derived from control and treated tobacco leaf tissues. A double-stranded oligonucleotide comprising both elements, and designated 3a4, was used as a probe. Results are shown in Figure 2B. When incubated with a protein extract prepared from control leaves, a retarded complex was detected, indicating that protein factor/s present in intact leaves recognize sequences within the probe. The interaction was sequence-specific, since addition of an excess of unlabeled probe prevented formation of the complex. Conversely, when using protein extracts derived from tobacco leaves that were detached from the plant and allowed to float for 24 h on a HEPES-buffered solution, the retarded complex was severely diminished. A similar DNA-binding activity was detected in protein extracts from intact, healthy tomato leaves (Figure 2B), which was also abrogated when protein extracts were derived from leaves systemically infected with tomato mosaic virus (ToMV).

Fig. 2. DNA–protein interactions in the CEVI1 minimal promoter. (A) Sequence of the 5′ end of the CEVI1 minimal promoter. The 3a4 probe used in EMSA is shown at the top. Numbers denote nucleotide positions relative to the ATG. Inverted GCC and direct TGTCTC boxes are shown in bold. Fragments used as cold competitors are shown below the sequence. Arrows mark the 5′ end of deletions used in the functional analysis of the CEVI1 promoter in transgenic plants. (B) EMSA using the 3a4 fragment as a probe and whole-cell extracts from control (C) and detached (D) tobacco leaves, and from healthy (H) and infected (I) tomato leaves. (–/+) symbols denote the absence and presence, respectively, of the relevant component. Comp., cold competitor. (C and D) Sequence specificity of the interaction as revealed by competition analysis. In (C), fragments derived from the CEVI1 minimal promoter outside and within the 3a4 element were used as cold competitors. In (D), the effect of different block mutations introduced in the context of the 3a4 element on competition ability was analyzed. Sequences of the respective mutations are shown on the left. Dashes denote unchanged nucleotides.

In order to more precisely define the binding site for this interaction, partly overlapping double-stranded oligonucleotides, designed to bear distinct sequences within, or adjacent to, the original 3a4 probe, were used as competitors in EMSA. As shown in Figure 2C, none of these oligonucleotides was able to compete binding to the 3a4 probe, not even when they were combined in the same binding reaction (data not shown), indicating that integrity of the 3a4 sequence was required for binding. As an alternative means to delimitate sequences involved in binding, different block mutations were introduced in the context of the original 3a4 probe and the corresponding double-stranded oligonucleotides used as cold competitors in EMSA. As shown in Figure 2D, oligonucleotides mut1, mut4 and mut6 were all able to efficiently compete binding to the 3a4 probe, whereas oligonucleotides mut2, mut3 and mut5 competed only partially. However, when block mutations 2 and 5 were simultaneously present in the same oligonucleotide (Figure 2D; mut7), no competition was observed. These results indicate that these two block mutations partially altered the target sequence for the protein/s present in the complex, although they did not prevent binding completely. Only when both were simultaneously introduced in the 3a4 probe sequence was the binding site completely dismantled, and the mutated sequence was not able to compete in binding to the probe. Therefore, the 14 bp sequence delimitated by block mutations 1 and 6 appears to be the target site for DBP1 binding.

Isolation of DBP1

To isolate cDNA clones encoding proteins capable of binding specifically to the 3a4 fragment of the CEVI1 proximal promoter, we screened a λZAP cDNA expression library prepared from tobacco leaves. As a probe, we utilized a tetramer of the 3a4 oligonucleotide. After three rounds of screening, six clones were selected out of ∼400 000 p.f.u. initially screened. Binding specificity for these six clones was analyzed by using a tetramer of the double-stranded mutant oligonucleotide mut7 that had lost competition ability in EMSA. Only one of the six clones isolated showed specific binding to the 3a4 probe (data not shown).

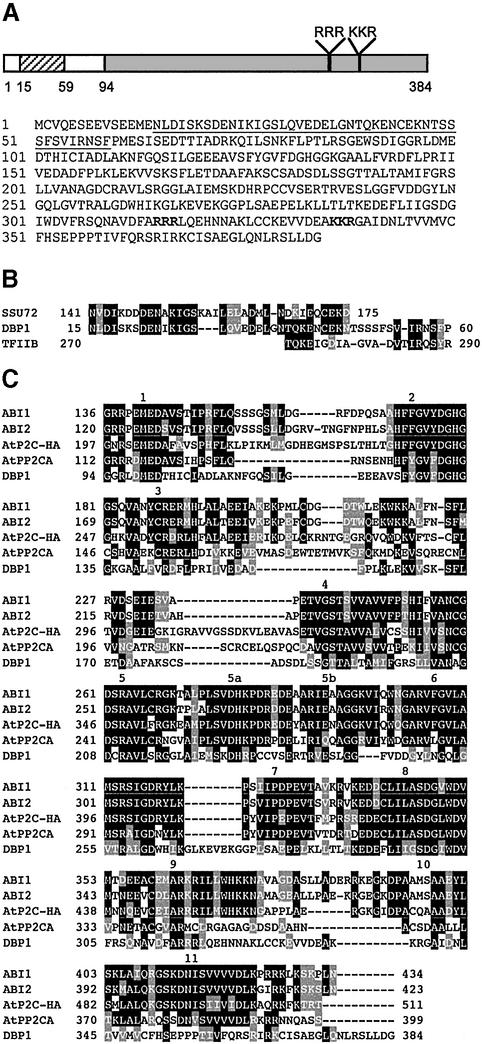

The selected cDNA clone was sequenced and characterized, and a full-length clone was isolated using circular 5′-RACE (Maruyama et al., 1995). The full-length sequence was 1504 nucleotides long with an open reading frame (ORF) of 1152 nucleotides, encoding a protein of 384 amino acid residues (Figure 3A), with a theoretical molecular mass of 42 196 Da. Sequence comparison in data bases revealed that the C-terminal part of the encoded protein (amino acids 136–384) shows homology to protein phosphatases, and in particular to the monomeric and Mg2+-dependent serine/threonine phosphatases of the 2C class (PP2C) (Smith and Walker, 1996) (Figure 3C). This homology was highest with domains participating in the coordination of phosphate and metal ions that are involved in catalysis (domains 1, 2 and 8; Figure 3C). In plants, PP2C phosphatases are characterized by the presence of specific N-terminal extensions of variable length that show no homology to each other, or to known protein sequences in data banks (Rodríguez,1998). The function of these N-terminal domains remains largely elusive although it has been hypothesized that they contribute to conferring functional specificity on the enzyme. Interestingly, the N-terminal part of the herein identified protein is rich in acidic amino acid residues, and shows (amino acids 15–60) significant homology to the yeast protein SSU72 (Figure 3B). Although the precise function of SSU72 is not known, it has been proposed to be functionally related to the general transcription factor TFIIB and participate in transcription start-site selection (Sun and Hampsey, 1996). Furthermore, the DNA-binding motif of TFIIB (Lagrange et al., 1998) also shares homology with the N-terminal region of the identified protein (Figure 3B). Due to this bipartite structure, i.e. the presence of the phosphatase and DNA binding domains, we propose to name this protein as DBP1 for DNA-binding protein phosphatase 1.

Fig. 3. DBP1 structure. (A) Deduced amino acid sequence of DBP1. The N-terminal domain showing homology to yeast SSU72 and human TFIIB is underlined. A putative bipartite NLS is shown in bold. (B) Alignment of the N-terminal sequence of DBP1 with a domain within yeast SSU72 protein and the DNA-binding domain of human TFIIB. Conserved amino acids are boxed in black, while gray boxes indicate conservative changes. (C) Sequence alignment of the C-terminal part of DBP1 with the core sequence of other plant PP2Cs. Accession Nos: ABI1, X77116 (Leung et al., 1994; Meyer et al., 1994); ABI2, Y08965 (Leung et al., 1997); AtP2C-HA, AJ003119 (Rodríguez et al., 1998); AtPP2CA, D38109 (Kuromori and Yamamoto, 1994). Numbers on the alignment refer to domains conserved among plant PP2Cs.

DBP1 has protein phosphatase activity

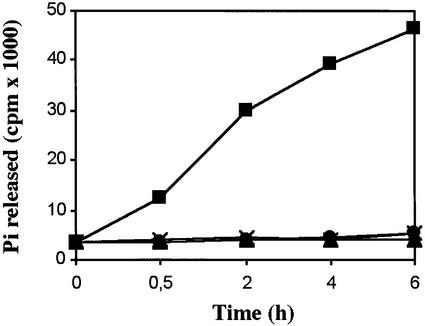

The cDNA sequence encoding DBP1 ORF was subcloned in the Escherichia coli expression vector pMAL for inducible expression of an in-frame translational fusion of DBP1 to the maltose-binding protein (MBP). A point mutation that abolishes protein phosphatase activity in the homologous ABI1 protein from Arabidopsis (abi1-R2 mutation; Gosti et al., 1999) was introduced in the DBP1 ORF (P280L), and the mutated protein was expressed in E.coli and affinity purified also as a translational fusion to MBP. As shown in Figure 4, the affinity-purified MBP–DBP1 fusion protein displayed Mg2+-dependent protein-phosphatase activity, measured as Pi released from phosphorylated casein. In contrast, mutated DBP1 completely lost activity when assayed in the same conditions. Purified MBP was used as a control.

Fig. 4. DBP1 has Mg2+-dependent protein phosphatase activity. Affinity-purified recombinant proteins were assayed for protein phosphatase activity against phosphorylated casein as described in Materials and methods. Release of radioactive Pi from phosphorylated casein was measured after incubation with MBP–DBP1 in the presence (squares) and in the absence (triangles) of 10 mM MgCl2, and with MBP-mutated DBP1 (crosses) and MBP alone (circles), both assayed in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2.

DBP1 contains a functional nuclear localization signal

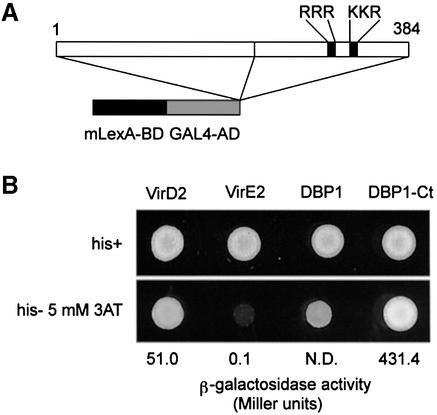

If DBP1 is indeed a DNA-binding protein involved in the transcriptional control of CEVI1 expression, it must localize to the cell nucleus. Inspection of the amino acid sequence of DBP1 revealed the presence of a putative bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Nigg, 1997) (RRR…KR) at positions 315–317 and 336–338 (Figure 3A). To test whether this NLS indeed functions to shuttle the DBP1 protein to the nucleus, we used a nuclear import assay developed in yeast for heterologous proteins (Rhee et al., 2000). As shown in Figure 5, both the C-terminal part of DBP1, containing the putative NLS, and the entire DBP1 protein were able to direct the tripartite fusion protein to the yeast nucleus to activate transcription. This nuclear entry occurred with high efficiency (quantified by β-galactosidase activity) when compared with that of the bona fide nuclear protein VirD2 (construct VirD2, Figure 5B), or with the lack of nuclear entry of the cytosolic VirE2 protein (construct VirE2, Figure 5B), used as a negative control (Rhee et al., 2000).

Fig. 5. DBP1 nuclear localization. (A) Constructs used in the yeast nuclear import assay. The position of the putative bipartite NLS is indicated. mLexA-BD, lexA DNA-binding domain devoid of any NLS; GAL4-AD, GAL4 activation domain. (B) DBP1-derived constructs support HIS3 and lacZ reporter gene activation in the yeast nuclear import assay. VirD2, effector construct bearing the nuclear protein VirD2 from A.tumefaciens, used as a positive control; VirE2, effector construct with the cytosolic protein VirE2 from A.tumefaciens, used as a negative control; DBP1, effector construct with full-length DBP1; DBP1-Ct, effector construct bearing the C-terminal part of DBP1; 3AT, 3-amino-triazole; N.D., not determined.

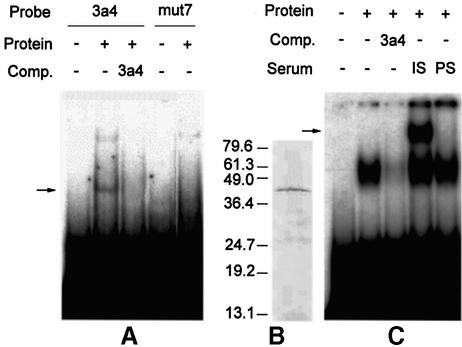

DBP1 shows in vitro sequence-specific DNA-binding activity and is part of the 3a4-binding complex

For the purpose of assaying and demonstrating its DNA-binding capacity, DBP1 fused to a C-terminal His6 tag (DBP1-His6) was expressed in E.coli. Affinity-purified DBP1-His6 was assayed by EMSA and found to bind the radioactively labeled 3a4 probe but not the mut7 probe (Figure 6A). This result demonstrates that DBP1, per se, is able to function as a DNA-binding protein and reproduces the sequence specificity previously observed in the Southwestern screening procedure and in EMSA using plant protein extracts. Furthermore, to demonstrate the participation of DBP1 in the formation of the protein–DNA complex within the CEVI1 gene promoter, a polyclonal antiserum was raised in rabbits against a synthetic peptide (ELGNTQKENCEKNT) derived from the N-terminal region of DBP1. Specificity of this antiserum was evaluated by western blotting using tobacco leaf protein extracts, where it immunodecorated a single polypeptide of the expected molecular weight (42 kDa; Figure 6B). When this antibody was included in the reaction mix in EMSA with plant protein extracts, the result was a supershift of the original protein–DNA complex (Figure 6C). This supershift was not observed when preimmune serum was included as a control in the reaction mix (Figure 6C). These results thus demonstrate that DBP1 is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that forms part of the protein–DNA complex inherent to the promoter sequence controlling transcription of the defense-related CEVI1 gene.

Fig. 6. DBP1 is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein and part of the plant-derived 3a4-binding complex. (A) EMSA showing specific binding of affinity-purified recombinant His6-tagged DBP1 to the 3a4 element (arrow), and not to the mut7 sequence. (–/+) symbols denote the absence and presence, respectively, of the relevant component. Comp., cold competitor. (B) Specificity of the polyclonal antiserum raised against DBP1 as assayed by western blotting with tobacco leaf protein extracts. Numbers on the left indicate the molecular mass of protein markers (in kDa). (C) Specific supershift (arrow) of the 3a4-binding complex observed with tobacco extracts upon addition of anti-DBP1 antiserum. IS, immune serum; PS, preimmune serum.

In vivo evidence for a direct role of DBP1 in CEVI1 transcriptional regulation

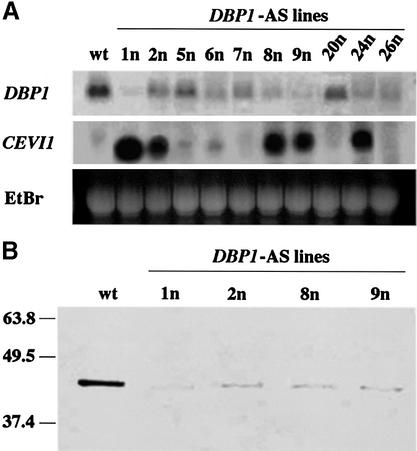

To further support the role of DBP1 in transcriptional regulation of CEVI1 expression, transgenic tobacco plants harbouring a DBP1-antisense construct under the control of the 35SCaMV promoter were generated and the steady-state level of accumulation of the endogenous DBP1 transcript in these transgenic lines was analyzed by northern blotting. Of 24 independent transgenic lines generated with this construct, five lines (lines 1n, 2n, 8n, 9n and 24n; Figure 7A) showed constitutive up-regulation of the CEVI1 gene at a high level, and in another two (lines 5n and 6n), CEVI1 transcript accumulation was weaker but still evident. In all of them the steady-state level of accumulation of the endogenous DBP1 mRNA was significantly reduced, with CEVI1 transcript level largely correlating with the magnitude of antisense inhibition of DBP1 expression, which was corroborated also at the protein level by western blotting as shown in Figure 7B. Even in lines with diminished DBP1 expression that do not accumulate high constitutive levels of the CEVI1 transcript, an earlier induction of CEVI1 gene expression was observed upon detachment with respect to the wild-type plant, which was accompanied by a significant reduction in the 3a4-binding activity detected by EMSA (data not shown). These results provide in vivo evidence for the participation of this new regulator in the transcriptional control of CEVI1 gene expression.

Fig. 7. (A) Antisense-mediated reduction of DBP1 expression results in constitutive CEVI1 transcript accumulation. Northern analysis of endogenous DBP1 and CEVI1 transcripts in wild-type (wt) and 10 independent DBP1-antisense tobacco lines. EtBr, ethidium bromide staining of RNA. (B) Western blot comparing DBP1 protein accumulation in wild-type tobacco plants and four DBP1-antisense transgenic lines. The molecular mass of protein markers is indicated on the left (in kDa).

Discussion

Transcriptional regulation of CEVI1 expression

Activation of defense responses in plants against pathogens largely relies on transcriptional induction of specific defense-related genes. Expression of the tomato CEVI1 gene appears to be controlled by a novel signaling pathway that is activated in susceptible plants during disease. Interestingly, CEVI1 gene expression is also induced by detachment (Mayda et al., 2000a,b) Functional analysis of the CEVI1 promoter in transgenic plants has revealed that sequences necessary for gene induction in response to detachment lie between positions –155 and –128 (Figure 1). Within that region of the CEVI1 promoter we have identified a novel cis-acting element that under resting conditions, when the gene is expressed at basal low levels, is specifically bound by leaf protein factor/s (Figure 2B). Formation of this complex is sensitive to detachment, with loss of binding and gene activation occurring concomitantly. These results suggest that the complex is acting by repressing transcription of the CEVI1 gene. The target sequence for this complex has been located between positions –118 and –132, flanked by two well-characterized plant cis-acting elements: an inverted ET-responsive GCC box and a TGTCTC element, core sequence of AuxREs. However, the DNA–protein complex we have observed in vitro does not directly involve either of these two boxes as shown by competition analysis (Figure 2C and D), but rather the sequence between them. This does not necessarily rule out the possibility that these two additional elements may play a role in the transcriptional control of the CEVI1 gene. The involvement of the identified element in the detachment responsiveness of the promoter is further supported by in vivo data. Disruption of this element in the context of the full-length promoter fused to the GUS reporter gene led to loss of inducibility in transgenic tobacco plants (see Figure 1, deletion d11). However, under these conditions, in which binding of the putative repressor complex should be impeded, CEVI1 gene expression is not up-regulated. A plausible explanation would be that the induction process requires an activator that does not bind to this truncated version of the CEVI1 promoter. A similar DNA-binding activity has been detected in leaves from tomato plants. Infection by ToMV, which promotes induction of CEVI1 expression in infected tissues of tomato plants (Mayda et al., 2000a), also results in a drastic attenuation of the observed binding. This finding reinforces the consideration that detachment and viral infection activate CEVI1 gene expression by similar, if not the same, signaling pathways (Mayda et al., 2000a).

DBP1 as a new transcriptional regulator

We have isolated a cDNA clone from tobacco, encoding a novel DNA-binding protein with protein phosphatase activity (DBP1), which is able to bind with specificity sequences within the 3a4 probe. Recombinant DBP1 expressed in E.coli displays both Mg2+-dependent protein phosphatase (Figure 4) and sequence-specific DNA-binding activitiy (Figure 6A). To our knowledge, this is the first report on the identification of a protein phosphatase with DNA-binding activity. As shown in Figure 3C, sequence comparison revealed that DBP1 bears catalytically important domains, like those putatively coordinating phosphate and metal ions, but lacks some domains conserved among other plant PP2Cs (Rodríguez, 1998). This may reflect functional specificity and/or differential regulation of DBP1. The N-terminal region, which is highly variable among plant PP2Cs, shows homology to transcription-related proteins (Figure 3B), such as the yeast SSU72 protein (Sun and Hampsey, 1996) and to the recently described DNA-binding domain of the human general transcription factor TFIIB (Lagrange et al., 1998).

To bind DNA and exert its function, DBP1 must localize to the cell nucleus. We have used a novel approach, developed by Rhee et al. (2000), to examine the cellular localization of DBP1 in vivo. Results shown in Figure 5 clearly show that DBP1 is targeted to the nucleus with high efficiency in yeast cells by means of a NLS located in the C-terminal half of the protein. Since the machinery involved in nuclear transport is generally well conserved among eukaryotic organisms (Nigg, 1997), DBP1 very likely also enters the nucleus in plant cells. However, besides modulating transcriptional activity of target genes in the nucleus by virtue of its sequence-specific DNA-binding capacity, DBP1 might play additional roles as a protein phosphatase also in the cytoplasm. In fact, we find very plausible the possibility that a shuttle system is controlling subcellular localization and thereby function of DBP1.

Detecting DBP1 in the protein–DNA complex binding to the 3a4 fragment would provide additional support for the participation of DBP1 in the transcriptional control of the expression of the CEVI1 gene. For that purpose, we used a specific polyclonal antiserum raised against a peptide derived from the N-terminus of DBP1 in EMSA. While addition of preimmune serum had no effect on binding, antibodies recognizing DBP1 caused a supershift of the original complex, indicating that DBP1 is part of it.

Collectively, these results strongly suggest that DBP1 is a new regulatory factor directly involved in transcriptional control by binding DNA with sequence specificity.

In vivo functional implication and possible roles of DBP1 in CEVI1 transcriptional regulation

By generating antisense transgenic plants we have been able to strongly reduce the expression level of the tobacco DBP1 gene. In most transgenic tobacco lines showing a severe reduction in DBP1 gene expression, the CEVI1 transcript accumulated constitutively at a level consistently correlating with the magnitude of the antisense effect on DBP1 expression. These results provide a strong in vivo evidence for the implication of DBP1 in the regulation of CEVI1 gene expression, and suggest a repressive role for this new regulator in controlling transcription of target genes. Protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation plays a major role in transcriptional regulation by modulating transcription factor function as well as the activity of coregulators and chromatin-remodelling factors (for review, see Whitmarsh and Davis, 2000). Changes in the phosphorylation status of a transcription factor may directly affect its cellular localization, stability, DNA-binding activity and/or its interaction with other proteins. Similarly, histone phosphorylation plays an important role in transcription activation as well. For instance, heat-shock gene induction in Drosophila is accompanied by dramatic incresases in histone H3 phosphorylation (Nowak and Corces, 2000). In addition, protein kinases and phosphatases also seem to modulate assembly of the preinitiation complex (PIC). The rate of formation of this complex is the ultimate target for transcription regulation. Phosphorylation appears to be involved in controlling assembly of PIC by modulating interactions among components of the general transcription machinery (Kitajima et al., 1994; Segil et al., 1996; Solow et al., 1999). Therefore, DBP1 might participate in the transcriptional regulation of the CEVI1 gene by dephosphorylating specific components of the general transcription machinery, thereby modulating their activity and the assembly of the PIC. DBP1 might also dephosphorylate chromatin-remodelling factors, preventing access of the PIC to the core promoter sequences or binding of an activator to its target site in the proximal CEVI1 promoter. Alternatively, such an activator could be the direct target of DBP1 phosphatase activity, negatively affecting its DNA-binding activity or promoting nuclear export.

Very recently, a mitogen-activated protein kinase, ERK5, has been described in mouse, which contains a transcriptional activation domain and functions as a coactivator in the transcriptional induction of genes involved in immature T cell apoptosis (Kasler et al., 2000). Both mouse ERK5 and tobacco DBP1 represent novel classes of regulatory molecules that provide a direct link between phosphorylation/dephosphorylation and transcriptional regulation, particularly in the case of DBP1, where a sequence-specific DNA-binding domain brings a protein phosphatase activity directly to a cis-acting element in the promoter of a downstream target gene. This protein binds with sequence-specificity to a new cis-acting element we have identified in the promoter of the CEVI1 gene from tomato, a gene that appears to be regulated by a new signaling pathway controlling disease susceptibility in plants (Mayda et al., 2000b), which is also activated upon detachment. The identification of proteins interacting with DBP1 will be crucial for the elucidation of the molecular mechanism utilized in DBP1-dependent transcriptional regulation, and the further characterization of the signaling network involved in controlling CEVI1 transcription.

Materials and methods

Plant transformation

5′ and internal deletions of the CEVI1 promoter were subcloned into the binary vector pBI101 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), resulting in transcriptional fusions to the coding sequence of the GUS reporter gene. For the DBP1 antisense construct, the sequence coding for the N-terminal extension was amplified by PCR using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, San Diego, CA) and subcloned in antisense orientation into the binary vector pBI121 (Clontech) under the control of the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter. Constructs were introduced into tobacco (N.tabacum cv. Xanthi-NC) via Agrobacterium tumefaciens as described previously (Tornero et al., 1997). F1 seeds were germinated on selective MS agar medium containing kanamycin, and transgenic seedlings were then transferred to soil. Reporter gene expression was analyzed by assaying GUS activity in situ with the colorigenic substrate X-gluc (Jefferson, 1987).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Leaf whole-cell extracts were prepared as described previously (Foster et al., 1992). As a probe, a double-stranded oligonucleotide (3a4) was radioactively labeled by filling in SalI extensions on the 5′ and 3′ ends with the Klenow fragment of the E.coli DNA polymerase I. Binding reactions contained 8 fmol of probe and 20 µg of leaf protein in 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.6, 40 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 200 µg/ml BSA, 10% glycerol in the presence of 200 ng poly(dI–dC)·poly(dI–dC), and were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. DNA–protein complexes were separated from free DNA probe by electrophoresis on native 6% (38:2) polyacrylamide gels run in 0.5× TBE at 4°C.

Southwestern screening

A λZAP cDNA library from tobacco leaves (Herbers et al., 1995) was screened following a denaturation/renaturation protocol as described previously (Somssich and Weisshaar, 1996), using a radioactively labeled tetramerized 3a4 element as a probe.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis

DNA sequencing was performed on an ABI PRISM DNA sequencer 377 (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). Sequence homology searches were conducted using the BLAST programs (Altschul et al., 1997). Additional computer-assisted analyses of DNA sequences were performed using the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (GCG) package (Genetics Computer Group, Inc., Madison, WI).

Production of recombinant DBP1

The coding sequence of DBP1 was amplified by PCR using Pfu DNA polymerase and subcloned into the pMAL vector (New England Biolabs, Schwalbach, Germany) for expression in E.coli as a translational fusion to the MBP, and into the pET28a vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) for DBP1 C-terminal His6 tagging. Recombinant proteins were affinity-purified through an amylose column (New England Biolabs) and a nickel–agarose column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), respectively, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The mutation that renders ABI1 protein catalytically inactive in the Arabidopsis abi1-R2 mutant was introduced into DBP1 ORF by site-directed mutagenesis using the primer 5′-GCTTTAGTTCTAGTTCAGCACTCA-3′, following the megaprimer method (Datta, 1995). The underlined nucleotide is the one causing the relevant P280L amino acid substitution.

Protein phosphatase activity

Protein phosphatase activity was determined essentially as described previously (Meskiene et al., 1998), using radiolabeled casein as a substrate. Release of radioactive Pi was measured by liquid scintillation counting after incubation with the relevant affinity-purified recombinant protein at room temperature for the indicated time.

Yeast nuclear import assay

Both the entire coding sequence and the C-terminal part of DBP1 (amino acids 213–384) containing the putative NLS were subcloned into the pNIA yeast shuttle vector, in-frame with the chimeric mLexA-GAL4AD protein (Rhee et al., 2000). The resulting plasmid was introduced into the yeast strain L40 (Hollenberg et al., 1995) following a PEG-LiAc procedure (Kaiser et al., 1994). Transformed yeast was analyzed for reporter gene activation. For the HIS3 gene, yeast was plated on selective SD medium lacking histidine and supplemented with 5 mM 3-aminotriazol (3AT). For the lacZ gene, yeast was grown on X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) indicator plates. LacZ gene activation was quantified by measuring β-galactosidase activity in liquid cultures using ONPG (O-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) as a substrate.

Production of polyclonal antiserum

A polyclonal antiserum was generated against a peptide derived from the N-terminal part of DBP1, selected on the basis of structure and antigenicity predictions obtained using the GCG software package. Peptide synthesis and production of the antiserum were carried out at Gramsch Laboratories (Schwabhausen, Germany).

Western blotting

A crude leaf extract from tobacco was prepared in 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.6, 40 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 0.5 mM PMSF. SDS–PAGE and western blotting were performed according to standard procedures. A 1:1000 dilution of the anti-DBP1 antiserum was used.

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No.

Tobacco DBP1 cDNA sequence has been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database under accession No. AF520810.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr U.Sonnewald (IPK, Gatersleben, Germany) for providing the tobacco leaf cDNA expression library, and Dr V.Citovsky (State University of New York, Stony Brook, USA) for the yeast nuclear import system and for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Agrios G.N. (1988) Plant Pathology. Academic Press, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schäffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl J.L. and Jones,J.D. (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defense responses to infection. Nature, 411, 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta A.K. (1995) Efficient amplification using ‘megaprimer’ by assymetric polymerase chain reaction. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 4530–4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. (1998) SA, JA, ethylene, and disease resistance in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 1, 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster R., Gasch,A., Kay,S. and Chua,N.-H. (1992) Analysis of protein–DNA interactions. In Koncz,C., Chua,N.-H. and Schell,J. (eds), Methods in Arabidopsis Research. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore, pp. 378–392. [Google Scholar]

- Gaits F., Shiozaki,K. and Russell,P. (1997) Protein phosphatase 2C acts independently of stress-activated kinase cascade to regulate the stress response in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 17873–17879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. (2001) Genes controlling expression of defense responses in Arabidopsis—2001 status. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 4, 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosti F., Beaudoin,N., Serizet,C., Webb,A.A.R., Vartanian,N. and Giraudat,J. (1999) ABI1 protein phosphatase 2C is a negative regulator of abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell, 11, 1897–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbers K., Mönke,G., Badur,R. and Sonnewald,U. (1995) A simplified procedure for the subtractive cDNA cloning of photoassimilate-responding genes: isolation of cDNAs encoding a new class of pathogenesis-related proteins. Plant Mol. Biol., 29, 1027–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg S.M., Sternglanz,R., Cheng,P.F. and Weintraub,H. (1995) Identification of a new family of tissue-specific basic helix–loop–helix proteins with a two-hybrid system. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 3813–3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson R.A. (1987) Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 5, 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C., Michaelis,S. and Mitchell,A. (1994) Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 201–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kasler H.G., Victoria,J., Duramad,O. and Winoto,A. (2000) ERK5 is a novel type of mitogen-activated protein kinase containing a transcriptional activation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8382–8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima S., Chibazakura,T., Yonaha,M. and Yasukochi,Y. (1994) Regulation of the human general transcription initiation factor TFIIF by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 29970–29977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel B.N. and Brooks,D.N. (2002) Cross talk between signaling pathways in pathogen defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 5, 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T. and Yamamoto,M. (1994) Cloning of cDNAs from Arabidopsis thaliana that encode a putative protein phosphatase 2C and a human Dr1-like protein by transformation of a fission yeast mutant. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 5296–5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrange T., Kapanidis,A.N., Tang,H., Reinberg,D. and Ebright,R.H. (1998) New core promoter element in RNA-polymerase II-dependent transcription: sequence-specific DNA binding by transcription factor IIB. Genes Dev., 12, 34–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J. et al. (1994) Arabidopsis ABA response gene ABI1: features of a calcium-modulated protein phosphatase. Science, 264, 1448–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J., Merlot,S. and Giraudat,J. (1997) The Arabidopsis abscisic acid-insensitive2 (ABI2) and ABI1 genes encode homologous protein phosphatases 2C involved in abscisic acid signal transduction. Plant Cell, 9, 759–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loake G.J., Faktor,O., Lamb,C.J. and Dixon,R.A. (1992) Combination of H-box [CCTACC(N)7CT] and G-box (CACGTG) cis elements is necessary for feed-forward stimulation of a chalcone synthase promoter by the phenylpropanoid-pathway intermediate p-coumaric. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 9230–9234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T., Wurgler-Murphy,S.M. and Saito,H. (1994) A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature, 369, 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama I.N., Rakow,T.L. and Maruyama,H.I. (1995) cRACE: a simple method for identification of the 5′ end of mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3796–3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayda E., Marqués,C., Conejero,V. and Vera,P. (2000a) Expression of a pathogen-induced gene can be mimicked by auxin insensitivity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact., 13, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayda E., Mauch-Mani,B. and Vera,P. (2000b) Arabidopsis dth9 mutation identifies a gene involved in regulating disease susceptibility without affecting salicylic acid-dependent responses. Plant Cell, 12, 2119–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlot S., Gosti,F., Guerrier,D., Vavasserie,A. and Giraudat,J. (2001) The ABI1 and ABI2 protein phosphatases 2C act in a negative feedback regulatory loop of the abscisic acid signaling pathway. Plant J., 25, 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meskiene I., Bögre,L., Glaser,W., Balog,J., Brandstötter,M, Zwerger,K., Ammerer,G. and Hirt,H. (1998) MP2C, a plant protein phosphatase 2C, functions as a negative regulator of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in yeast and plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 1938–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K., Leube,M.P. and Grill,E. (1994) A protein phosphatase 2C involved in ABA signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science, 264, 1452–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E.A. (1997) Nucleocytoplasmic transport: signals, mechanisms and regulation. Nature, 386, 779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak S.J. and Corces,V.G. (2000) Phosphorylation of histone H3 correlates with transcriptionally active loci. Genes Dev., 14, 3003–3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme-Takagi M. and Shinshi,H. (1995) Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell, 7, 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee Y., Gurel,F., Gafni,Y., Dingwall,C. and Citovsky,V. (2000) A genetic system for detection of protein nuclear import and export. Nat. Biotechnol., 18, 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez P.L. (1998) Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) function in higher plants. Plant Mol. Biol., 38, 919–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez P.L., Leube,M.P. and Grill,E. (1998) Molecular cloning in Arabidopsis thaliana of a new protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) with homology to ABI1 and ABI2. Plant Mol. Biol., 38, 879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A.F. (1961) Systemic acquired resistance induced by localized virus infections in plants. Virology, 14, 340–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton P.J. and Somssich,I.E. (1998) Transcriptional control of plant genes responsive to pathogens. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 1, 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals J.A., Neuenschwander,U.H., Willits,M.G., Molina,A., Steiner,H.-Y. and Hunt,M.D. (1996) Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell, 8, 1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segil N., Guermah,M., Hoffmann,A., Roeder,R.G. and Heintz,N. (1996) Mitotic regulation of TFIID: inhibition of activator-dependent transcription and changes in subcellular localization. Genes Dev., 10, 2389–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen J. (1996) Ca2+-dependent protein kinases and stress signal transduction in plants. Science, 274, 1900–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenolikar S. (1994) Protein serine/threonine phosphatases—new avenues for cell regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell. Biol., 10, 55–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.D. and Walker,J.C. (1996) Plant protein phosphatases. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol., 47, 101–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solow S.P., Lezina,L. and Lieberman,P.M. (1999) Phosphorylation of TFIIA stimulates TATA binding protein–TATA interaction and contributes to maximal transcription and viability in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 2846–2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somssich I.E. and Weisshaar,B. (1996) Expression library screening. In Foster,G.D. and Twell,D. (eds), Plant Gene Isolation: Principles and Practice. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY, pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.-W. and Hampsey,M. (1996) Synthetic enhancement of a TFIIB defect by a mutation in SSU72, an essential yeast gene encoding a novel protein that affects transcription start site selection in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 1557–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa M., Maeda,T. and Saito,H. (1998) Protein phosphatase 2Cα inhibits the human stress-responsive p38 and JNK MAPK pathways. EMBO J., 17, 4744–4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornero P., Gadea,J., Conejero,V. and Vera,P. (1997) Two PR-1 genes from tomato are differentially regulated and reveal a novel mode of expression for a pathogenesis-related gene during the hypersensitive response and development. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact., 10, 624–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T., Liu,Z.-B., Hagen,G. and Guilfoyle,T.J. (1995) Composite structure of auxin-response elements. Plant Cell, 7, 1611–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wera S. and Hemmings,B.A. (1995) Serine/threonine protein phosphatases. Biochem. J., 311, 17–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh A.J. and Davis,R.J. (2000) Regulation of transcription factor function by phosphorylation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 57, 1172–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]