Abstract

Early nutrition affects adult metabolism in humans and other mammals, potentially via persistent alterations in DNA methylation. With viable yellow agouti (Avy) mice, which harbor a transposable element in the agouti gene, we tested the hypothesis that the metastable methylation status of specific transposable element insertion sites renders them epigenetically labile to early methyl donor nutrition. Our results show that dietary methyl supplementation of a/a dams with extra folic acid, vitamin B12, choline, and betaine alter the phenotype of their Avy/a offspring via increased CpG methylation at the Avy locus and that the epigenetic metastability which confers this lability is due to the Avy transposable element. These findings suggest that dietary supplementation, long presumed to be purely beneficial, may have unintended deleterious influences on the establishment of epigenetic gene regulation in humans.

Human epidemiologic and animal model data indicate that susceptibility to adult-onset chronic disease is influenced by persistent adaptations to prenatal and early postnatal nutrition (1, 2, 13, 14); however, the specific biological mechanisms underlying such adaptations remain largely unknown. Cytosine methylation within CpG dinucleotides of DNA acts in concert with other chromatin modifications to heritably maintain specific genomic regions in a transcriptionally silent state (4). Genomic patterns of CpG methylation are reprogrammed in the early embryo and maintained thereafter (20). Because diet-derived methyl donors and cofactors are necessary for the synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine, required for CpG methylation (23), early nutrition may therefore influence adult phenotype via DNA methylation (26).

Accordingly, it is important to identify genomic regions that are likely targets for early nutritional influences on CpG methylation. Most regions of the adult mammalian genome exhibit little interindividual variability in tissue-specific CpG methylation levels. Conversely, CpG methylation is determined probabilistically at specific transposable element insertion sites in the mouse genome, causing cellular epigenetic mosaicism and individual phenotypic variability (19). Transposable elements (including retrotransposons and DNA transposons) are parasitic elements which are scattered throughout and constitute over 35% of the human genome (32). Most transposable elements in the mammalian genome are normally silenced by CpG methylation (32). The epigenetic state of a subset of transposable elements, however, is metastable and can affect regions encompassing neighboring genes. (19). We hypothesized that the epigenetic metastability of such regions renders them susceptible to nutritional influences during early development.

We tested this hypothesis in viable yellow agouti (Avy) mice. The murine agouti gene encodes a paracrine signaling molecule that signals follicular melanocytes to switch from producing black eumelanin to yellow phaeomelanin. Transcription is initiated from a hair cycle-specific promoter in exon 2 of the agouti (A) allele (Fig. 1A). Transient agouti expression in hair follicles during a specific stage of hair growth results in a subapical yellow band on each hair, causing the brown (agouti) coat color of wild-type mice (8). The nonagouti (a) allele was caused by a loss-of-function mutation in A (5); a/a homozygotes are therefore black. The Avy allele (Fig. 1A) resulted from the insertion of an intracisternal A particle (IAP) retrotransposon into the 5′ end of the A allele (8). Ectopic agouti transcription is initiated from a cryptic promoter in the proximal end of the Avy IAP. CpG methylation in this region varies dramatically among individual Avy mice and is correlated inversely with ectopic agouti expression. This epigenetic variability causes a wide variation in individual coat color (Fig. 2A), adiposity, glucose tolerance, and tumor susceptibility among isogenic Avy/a littermates (15).

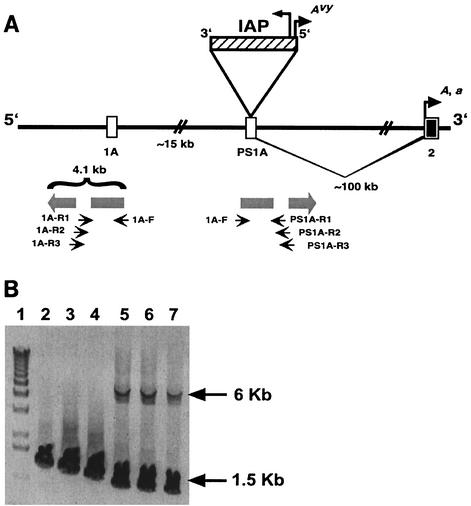

FIG. 1.

IAP insertion site in Avy allele. (A) Exon 1A of the murine agouti gene lies within an interrupted 4.1-kb inverted duplication (shaded block arrows). The duplication gave rise to pseudoexon 1A (PS1A). On the A allele, PS1A is located ≈100 kb upstream of exon 2 and ≈15 kb downstream of the contraoriented exon 1A (6). The Avy mutation was caused by a contraoriented IAP insertion (striped bar; tall arrowhead shows direction of IAP transcription). A cryptic promoter within the long terminal repeat proximal to the agouti gene (short arrowhead labeled Avy) drives ectopic agouti expression in Avy animals. In A and a animals, transcription starts from a hair cycle-specific promoter in exon 2 (short arrowhead labeled A, a). Small arrows show the positions of PCR primers used to selectively amplify the exon 1A and PS1A regions. (B) Agarose gel showing products of long-range PCR of Avy/a genomic DNA. Forward (F) and reverse (R) primers are described relative to the direction of the inverted duplicate regions and are shown in A. The same forward primer was used in all reactions. Three different reverse primers specific to the PS1A region (lanes 5 to 7) amplified fragments of ≈1.4 kb (the a allele) and ≈6 kb (the Avy allele, including the IAP insert). Three different reverse primers specific to the exon 1A region (lanes 2 to 4) amplified only the smaller fragments (≈1.6 kb). The exon 1A fragments are larger than the PS1A a fragments due to the more distal location of the exon 1A reverse primers.

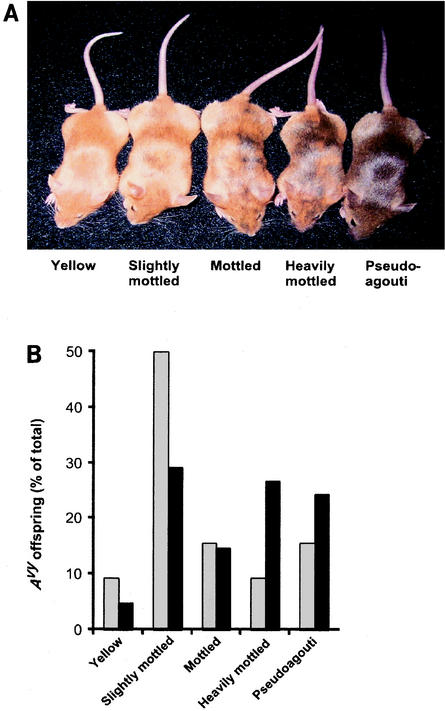

FIG. 2.

Maternal dietary methyl supplementation and coat color phenotype of Avy/a offspring. (A) Isogenic Avy/a animals representing the five coat color classes used to classify phenotype. The Avy alleles of yellow mice are hypomethylated, allowing maximal ectopic agouti expression. Avy hypermethylation silences ectopic agouti expression in pseudoagouti animals (15), recapitulating the agouti phenotype. (B) Coat color distribution of all Avy/a offspring born to nine unsupplemented dams (30 offspring; shaded bars) and 10 supplemented dams (39 offspring; black bars). The coat color distribution of supplemented offspring is shifted toward the pseudoagouti phenotype compared to that of unsupplemented offspring (P = 0.008).

Dietary methyl supplementation of a/a dams shifts the coat color distribution of their Avy/a offspring (30). Because Avy/a coat color correlates with Avy methylation status (15), it has been inferred that supplementation alters phenotype via Avy methylation (7). Nevertheless, no study has yet compared Avy methylation among the offspring of supplemented and unsupplemented dams (25). Therefore, to test our hypothesis that transposable elements are targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation, we had to determine if CpG methylation plays a role in diet-induced phenotypic alterations in Avy/a mice.

Agouti pseudoexon 1A (PS1A) was formed when a 4.1-kb genomic region containing exon 1A underwent duplication and inversion (Fig. 1A) (6). In mice that carry the light-bellied agouti (Aw) allele, exon 1A is oriented properly with respect to the agouti gene and drives agouti expression (and yellow pigmentation) throughout the hair growth cycle in ventral follicles. The orientation of the duplication is reversed in mice carrying the A allele (Fig. 1A). In these animals, exon 1A points away from agouti, causing a loss of ventral follicle-specific agouti expression (6). Early genetic analyses concluded that the Avy IAP is located within agouti exon 1A (8); however, this conclusion has not been reevaluated since the subsequent characterization of the inverted repeat in the region (6).

In this study, after determining the actual location of the Avy IAP, we showed that dietary methyl donor supplementation of a/a dams alters Avy/a offspring phenotype by increasing CpG methylation at the Avy locus. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the epigenetic metastability which confers this lability is due to the Avy IAP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and diets.

Avy mice were obtained from the colony at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (29). The Avy mutation arose spontaneously in the C3H/HeJ strain. Mice carrying the mutation were backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice for one to three generations before being propagated by sibling mating. These animals therefore include 6.25% to 25% of the C3H/HeJ genome and 75% to 93.75% of the C57BL/6J genome (31). This congenic colony has been propagated by sibling mating and forced heterozygosity for the Avy allele for over 200 generations, resulting in an essentially invariant genetic background.

Virgin a/a females, 8 weeks of age, were assigned randomly to NIH-31 diet or NIH-31 supplemented with the methyl donors and cofactors folic acid, vitamin B12, choline chloride, and anhydrous betaine (Harlan Teklad) (30). All ingredients were provided by Harlan Teklad except for the anhydrous betaine (Finnsugar Bioproducts). The diets were provided for 2 weeks before the females were mated with Avy/a males and throughout pregnancy and lactation. Upon weaning to a stock maintenance diet at age 21 days, the Avy/a offspring were weighed, tail tipped, photographed, and rated for coat color phenotype (Fig. 2A). Animals in this study were maintained in accordance with all relevant federal guidelines, and the study protocol was approved by the Duke University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Phenotypic classification.

The coat color phenotype of Avy/a mice was assessed at 21 and 100 days of age. A single observer classified coat color by visual estimation of the proportion of brown fur: yellow (<5% brown), slightly mottled (≥5% but less than half), mottled (about half), heavily mottled (greater than half but ≤95%), and pseudoagouti (>95%). The term pseudoagouti is used to describe Avy/a animals in which ectopic agouti expression was silenced (or nearly silenced) by CpG methylation, recapitulating the brown agouti phenotype of an A/− mouse.

Long-range PCR.

The Expand Long-Template PCR system (Roche) was used per the manufacturer's instructions. Primers were designed to amplify either the PS1A or exon 1A region (6) from genomic DNA (22): exon 1A forward, 1A-F (TCAGATTCTGGAGTGACAGATAGATCC) and reverse, 1A-R1 (TTCCAGGATTCATCAATAATCGCT), 1A-R2 (AGGTACTGAAATTAACACGGCGTT), and 1A-R3 (GCGGAGAGACTTCTAAATTATTCCGT); PS1A forward, 1A-F, and reverse, PS1A-R1 (AAAGCATTTTTGAAGAAAACCATGAATC), PS1A-R2 (GAAGAAAACCATGAATCAGAAAGGATTTAG), and PS1A-R3 (TGAATCAGAAAGGATTTAGTAAAATGGCTC).

Genomic sequencing.

The PS1A and exon 1A regions were amplified from genomic DNA (22) from two Avy/Avy and two a/a animals. The primers used were 1A-F and 1A-R1 in exon 1A and 1A-F and PS1A-R1 in PS1A (see above). The PCR products were gel purified and sequenced independently (Perkin Elmer dye terminator cycle sequencing system). Regions of identical sequence among isogenic homozygotes were assembled into contigs with GeneJockey II software (Biosoft).

Methylation assay.

A G/A single-nucleotide polymorphism (position 1092 in accession number AF540972, present in both exon 1A and PS1A) that allowed the a and Avy alleles to be cleaved selectively by AloI and SacI, respectively, was identified. We digested 0.5 μg of genomic DNA (22) overnight with 5 U of either AloI or SacI. Bisulfite modification was performed by a procedure adapted from the recently optimized protocol of Gruanau et al. (9). Specifically, each digested genomic DNA sample was precipitated with ethanol, washed, and denatured in 50 μl of 0.3 M NaOH (20 min at 37°C). Deamination was initiated by addition of 450 μl of a solution of saturated sodium bisulfite (Sigma) and 10 mM hydroquinone (Sigma), pH 5.0. Each sample was overlaid with mineral oil and incubated for 4 h at 55°C in the dark. The samples were desalted with the Wizard DNA clean-up system (Promega) and resolved in 50 μl 1 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0. DNA samples were desulfonated by addition of 5.5 μl of 3 M NaOH and incubation at 37°C for 20 min, then ethanol precipitated, washed in 75% ethanol, and suspended in 10 μl of 1 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0. Because of the possible differential stability of methylated and unmethylated DNA under long-term storage conditions, all studies were conducted with freshly isolated genomic DNA.

Bisulfite-modified DNA (4 μl) was PCR amplified in 50-μl reactions with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions (40 cycles). PCR bands were agarose gel purified (GenElute Minus EtBr Spin Columns; Sigma) and sequenced manually (Thermo Sequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit; USB Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing products were resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, with blank lanes between the C and T lanes to avoid signal overlap. Percent methylation at each CpG site was quantitated by phosphor imaging (percent methylation = 100 × [(C volume)/(C volume + T volume)]). Sequencing confirmed that endonuclease digestion was complete. The seven CpG sites studied in the PS1A region (and corresponding exon 1A region) are located at positions 910, 916, 934, 943, 956, 972, and 991 of accession number AF540972. These sites were chosen due to their relative proximity to the regions of dissimilarity between PS1A and exon 1A, enabling region-specific PCR amplification following bisulfite conversion. To analyze CpG methylation within the proximal long terminal repeat of the IAP, we PCR amplified the IAP-PS1A junction with the Avy IAP sequence (8). The nine CpG sites studied are located 138, 130, 124, 101, 80, 40, 27, 24, and 12 nucleotides upstream of the IAP-PS1A junction (8).

Primers used for bisulfite sequencing studies.

For the exon 1A region, we used forward primer 1ABF3 (ATTGTGGTGTAAATAGGTTAGATAG), reverse primer 1ABR3 (TAAACTAAATCAAAATACAAAACCCACC), and sequencing primer 1ABF4 (ATTGTGAATGAAATTTTTTGG). For the PS1A region, we used forward primer 1ABF3, reverse primer PS1ABR2 (CCATAAATCAAAAAAAATTTAATAAAATAAC), and sequencing primer 1ABF4. For the Avy IAP, we used forward primer IAPF3 (ATTTTTAGGAAAAGAGAGTAAGAAGTAAG), reverse primer IAPR4 (TAATTCCTAAAAATTTCAACTAATAACTCC), and sequencing primer IAPF5 (ATTATTTTTTGATTGTTGTAGTTTATGG).

Statistical analysis.

Because the supplements were provided to the dams, they were the appropriate units of analysis. Therefore, all analyses used within-litter averages for 9 litters (30 Avy/a offspring) and 10 litters (39 Avy/a offspring) for the unsupplemented and supplemented groups, respectively. Group comparisons of litter size and day 21 weights were performed by t test. Percent methylation data were not distributed normally and were therefore transformed dichotomously (<20% = 0, ≥20% = 1) before analysis. Relationships among supplementation, Avy methylation, and coat color were analyzed by mediational regression analysis (3) with SAS software.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The following sequence data were submitted to GenBank: Avy PS1A (accession number AF540972), a PS1A (accession number AF540973), Avy exon 1A (accession number AF540974), and a exon 1A (accession number AF540975).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To determine if the IAP insertion causes the epigenetic metastability in the Avy region, we needed first to determine the IAP location in the Avy allele. Exploiting sequence dissimilarities between exon 1A and PS1A (6) (Fig. 1A), long-range PCR was used to amplify the sequence bracketing the consensus IAP insertion site of both regions. This demonstrated clearly that the 4.5-kb IAP insert is contained within PS1A and not in exon 1A, as previously reported (8) (Fig. 1B).

To distinguish between the Avy and a alleles and thus enable Avy-specific quantitation of PS1A methylation in Avy/a mice, we sequenced the PS1A region downstream from the consensus IAP insertion site in a/a and Avy/Avy homozygotes. We identified and exploited a single-nucleotide polymorphism within an AloI consensus sequence to cleave the PS1A region of the a allele while leaving the Avy allele intact. Hence, by digesting genomic DNA with AloI and employing reverse primers specific to PS1A, bisulfite sequencing (9) was used to quantify site-specific CpG methylation of the Avy PS1A in Avy/a mice. Importantly, because each Avy/a cell contains only one copy of the Avy allele, our assay quantitates the percentage of cells in which each Avy CpG site examined is methylated.

Dietary supplementation of a/a dams throughout the reproductive cycle did not affect litter size or offspring body weight at age 21 days (data not shown). Supplementation did shift the coat color distribution of Avy/a offspring toward the brown (pseudoagouti) phenotype (Fig. 2B). To determine if this phenotypic change was caused by increased Avy CpG methylation, we quantitated PS1A CpG methylation at seven CpG sites (≈600 bp downstream from the IAP insertion site) in tail tip DNA from all Avy/a offspring born to nine unsupplemented and 10 supplemented dams. We chose to measure CpG methylation in this region for two reasons: (ii) amplification of bisulfite-treated DNA was more reliable in this region than in the IAP long terminal repeat, and (ii) the correlations between average percent methylation and coat color phenotype are comparable in the two regions (IAP long terminal repeat r2 = 0.82, downstream of PS1A r2 = 0.85), indicating that measurements of CpG methylation 600 bp downstream of the IAP insertion site are representative of average methylation levels throughout the PS1A region encompassing the Avy transcription start site.

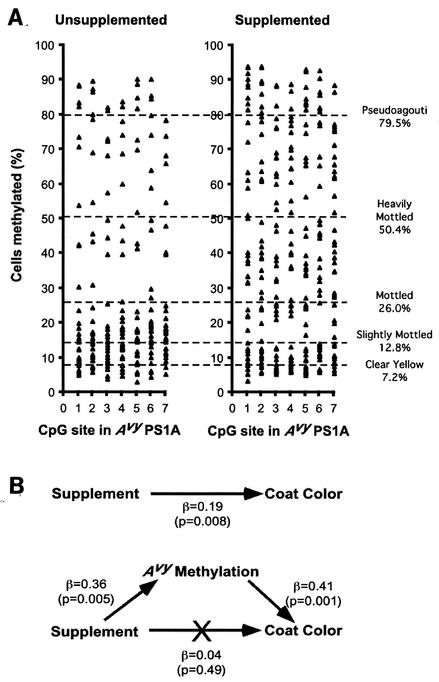

Percent methylation in Avy PS1A was distributed bimodally in unsupplemented Avy/a offspring (Fig. 3A), suggesting a probabilistic epigenetic switch that tends to assume one of two methylation states (19). Maternal supplementation caused a general increase in methylation at each site (Fig. 3A). We examined the relationships among supplementation, CpG methylation, and coat color by mediational regression analysis (3). The highly significant effect of supplementation on coat coloration vanished when Avy methylation was included in the model (Fig. 3B). This provides the first experimental evidence that Avy CpG methylation mediates the effect of supplementation on Avy/a coat color.

FIG. 3.

CpG methylation within the Avy PS1A of Avy/a offspring from unsupplemented and methyl-supplemented dams. (A) Percentage of cells methylated at each of seven CpG sites in the Avy PS1A in all Avy/a offspring of nine unsupplemented and 10 supplemented dams. DNA was isolated from tail tips at weaning. The seven CpG sites studied are located ≈600 bp downstream from the Avy IAP insertion site. Percent methylation is distributed bimodally in unsupplemented offspring, with less than 20% of the cells being methylated at each site in most animals. Maternal methyl supplementation increases mean methylation at each site, generating a more uniform distribution. Dotted lines show the average percent methylation across the seven sites in all Avy/a offspring according to coat color phenotype. (B) Mediational regression analysis (3) of supplementation, Avy methylation, and coat color. Supplementation significantly affects offspring coat color (top), but this relationship is nullified when Avy PS1A methylation is included in the regression model (bottom). This indicates that Avy CpG methylation is solely responsible for the effect of supplementation on coat color.

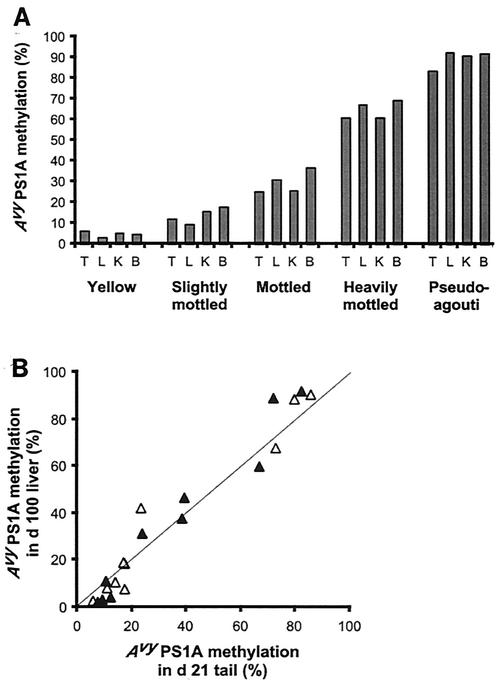

To determine if the nutritional effect on Avy PS1A methylation in tail DNA extends to other tissues, average percent methylation of Avy PS1A was also measured in liver, kidney, and brain samples from animals representing the five coat color phenotypes. PS1A methylation in the tail correlated highly with that in the other tissues (Fig. 4A). The tissues studied were derived from the three germ layers of the early embryo: endoderm (liver), mesoderm (kidney), and ectoderm (brain). These data thus indicate that Avy methylation is determined in the early embryo and maintained with high fidelity throughout development. This is consistent with previous studies showing high agouti expression in all tissues of yellow but not pseudoagouti Avy/a mice (31). Hence, the nutritional effect on Avy methylation likely occurs during early embryonic development and affects all tissues.

FIG. 4.

Avy PS1A methylation as a function of tissue type and animal age. (A) Average percent methylation of seven CpG sites in the Avy PS1A in tail (T), liver (L), kidney (K), and brain (B) samples from five Avy/a animals representing the five coat color classes shown in Fig. 2A. Avy methylation in the tail correlates highly with that in other tissues (r2 > 0.98 for all comparisons). (B) Average percent methylation of Avy PS1A in day 100 liver versus that in day 21 tail tip DNA. Percent methylation in day 21 tail predicts that in day 100 liver (r2 = 0.95). Open triangles, unsupplemented offspring; solid triangles, supplemented offspring. Neither group departed significantly from the line of identity (shown). Hence, Avy PS1A methylation is maintained with high fidelity into adulthood.

Coat color phenotype and Avy methylation also persisted to adulthood. Independent classification of coat color phenotype at age 100 days agreed with the day 21 classification in 48 of 50 Avy/a mice (data not shown). Similarly, mean Avy PS1A methylation in day 21 tail DNA predicted that in day 100 liver DNA (Fig. 4B). These data further support the idea that Avy PS1A methylation levels in tail DNA reflect those in other tissues and demonstrate that average Avy methylation is maintained quantitatively from weaning to adulthood. Hence, transient exposure of Avy/a mice to methyl supplementation in utero causes a shift in epigenotype that persists to influence the adult phenotype.

Alleles such as Avy, whose epigenetic marks are determined probabilistically but subsequently maintained stably, have been termed metastable epialleles (19). Metastable epialleles are commonly associated with transposable elements (19), which can interfere with the expression of neighboring genes (27). Nonetheless, it remains unclear if the epigenetic metastability of the Avy allele is due to the IAP insert or if some unique characteristic of the PS1A sequence contributes to its probabilistic variability in CpG methylation. Because the exon 1A region is nearly identical to the PS1A region (Fig. 1A), it provides an ideal cis negative control region by which to examine the IAP's influence on epigenetic metastability. Similarly, the PS1A region on the a allele of Avy/a heterozygotes provides a negative control region in trans.

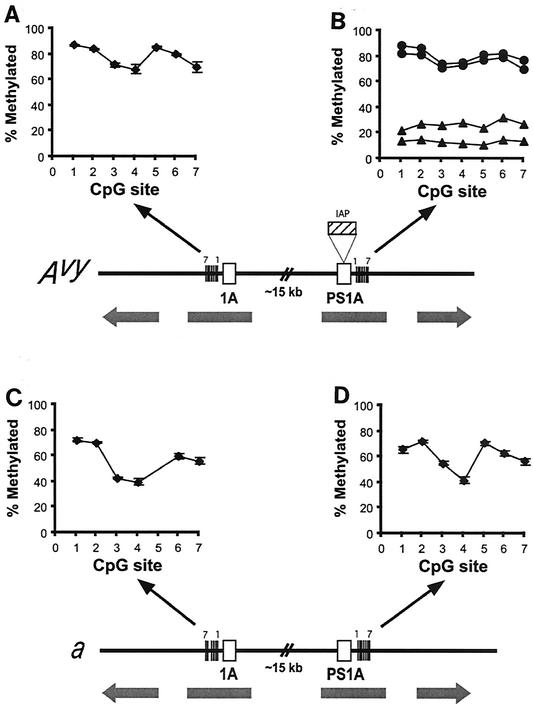

We therefore measured site-specific methylation of seven homologous CpG sites within exon 1A and PS1A of the a and Avy alleles in Avy/a animals of divergent phenotypes (Fig. 5). The extreme interindividual variability of Avy PS1A (P < 0.0001 by analysis of variance; Fig. 5B) was not observed in consensus sites within PS1A and exon 1A on the a allele (Fig. 5C and D). Instead, methylation in those regions was tightly regulated in a site-specific fashion and did not differ significantly among individuals. Notably, the interindividual coefficient of variation in percent methylation at each site was only slightly greater than that obtained by serial digestion and bisulfite sequencing of replicate DNA samples from a single individual (data not shown). Percent methylation at individual CpG sites was quantitatively similar between the two regions on a. Methylation of Avy exon 1A, which lies approximately 15 kb upstream of the IAP, was also not significantly different among individual mice (Fig. 5A), but was hypermethylated relative to consensus sites on the a allele (P < 0.0001). Clearly, the epigenetic metastability that renders Avy nutritionally labile is associated with the IAP insertion.

FIG. 5.

Percentage of cells methylated at each of seven CpG sites in Avy exon 1A (A), Avy PS1A (B), a exon 1A (C), and a PS1A (D). Each graph shows data from the same two slightly mottled and two pseudoagouti Avy/a animals (four total). In the Avy PS1A region (B), CpG methylation correlates with coat color; the pseudoagouti animals (circles) were heavily methylated, and the slightly mottled animals (triangles) were hypomethylated. In the other three regions (A, C, and D), methylation was independent of coat color (each point shows the mean ± standard error of the mean). On the a allele, methylation was tightly regulated and site dependent and did not differ significantly between the exon 1A and PS1A regions (C and D). Note that CpG site 5 is missing in the exon 1A region of the a allele in C due to a single-nucleotide polymorphism. The Avy exon 1A region (A) was hypermethylated relative to consensus sites on the a allele (P < 0.0001). Given the 99% sequence identity of these four regions, the epigenetic metastability of Avy PS1A is clearly associated with the neighboring IAP.

Conversely, proximity to PS1A apparently destabilizes IAP methylation. We performed bisulfite sequencing of the IAP/PS1A junction to quantify methylation at nine CpG sites within the cryptic promoter of the IAP (data not shown). Each animal's average percent methylation in the PS1A region was predicted by that in the neighboring IAP regardless of maternal diet (r2 = 0.92, n = 22 animals). Hence, whereas most IAPs in the mouse genome are heavily methylated (24), methylation at the Avy IAP correlates with that in the neighboring PS1A region and varies dramatically among individuals. Therefore, epigenetic metastability at the Avy locus occurs via a mutual interaction between a transposable element and its specific genomic region.

These results indicate that epigenetic metastability caused by juxtaposition of transposable elements and genomic promoter region DNA renders a subset of mammalian genes epigenetically labile to the effects of nutrition and other environmental influences during early development. Our findings have important implications for humans because transposable elements constitute over 35% of the human genome (32) and are found within about 4% of human genes (16). Furthermore, many human genes are transcribed from a cryptic promoter within the L1 retrotransposon (17), analogous to ectopic agouti transcription originating in the Avy IAP. It has been proposed that transposable elements in the mammalian genome cause considerable phenotypic variability, making each individual mammal a “compound epigenetic mosaic” (27). Our results provide compelling evidence that the specific composition of each individual's “epigenetic mosaic” is influenced by early nutrition.

Our findings are also important in the context of epigenetic inheritance at the Avy locus. When Avy/a animals inherit the Avy allele maternally, agouti expression and coat color phenotype are correlated with maternal phenotype in that yellow dams produce fewer pseudoagouti offspring than do pseudoagouti dams (28, 30). This phenotypic inheritance was originally attributed to a maternal effect on metabolic differentiation (28). A recent study (15), however, suggests that this parental effect is caused by incomplete erasure of epigenetic marks at the Avy locus in the female germ line. Our findings show that early nutrition can influence the establishment of epigenetic marks at the Avy locus in the early embryo, thereby affecting all tissues, including, presumably, the germ line. Hence, incomplete erasure of nutritionally induced epigenetic alterations at Avy provides a plausible mechanism by which adaptive evolution (10) may occur in mammals.

The moderate nature of the nutritional treatment used in these studies further underscores their relevance to humans. Whereas severe methyl donor deficiency has been demonstrated to induce gene-specific DNA hypomethylation in rodents (12), we show here that merely supplementing a mother's nutritionally adequate diet with extra folic acid, vitamin B12, choline, and betaine can permanently affect the offspring's DNA methylation at epigenetically susceptible loci. This finding supports the conjecture that population-based supplementation with folic acid, intended to reduce the incidence of neural tube defects, may have unintended influences on the establishment of epigenetic gene-regulatory mechanisms during human embryonic development (21).

It is increasingly evident that epigenetic gene regulatory mechanisms play important roles in the etiology of human diseases (11, 18). Our findings demonstrate that mammalian metastable epialleles associated with transposable elements enable early environmental influences, including nutrition, to persistently affect these important regulatory mechanisms. Hence, epigenetic alterations at metastable epialleles are a likely mechanistic link between early nutrition and adult chronic disease susceptibility.

Acknowledgments

We thank George Wolff for providing Avy animals, Michael Babyak for statistical advice, and Kay Nolan and Susan Murphy for suggestions on the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Dannon Institute fellowship (R.A.W.) and NIH grants CA25951 and ES08823.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barker, D. J. 1997. Intrauterine programming of coronary heart disease and stroke. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 423:178-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker, D. J. 1994. Programming the baby, p. 14-36. In D. J. Barker (ed.), Mothers, babies, and disease in later life. BMJ Publishing Group, London, UK.

- 3.Baron, R. M., and D. A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51:1173-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird, A. 2002. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 16:6-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bultman, S. J., E. J. Michaud, and R. P. Woychik. 1992. Molecular characterization of the mouse agouti locus. Cell 71:1195-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, Y., D. M. Duhl, and G. S. Barsh. 1996. Opposite orientations of an inverted duplication and allelic variation at the mouse agouti locus. Genetics 144:265-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooney, C. A., A. A. Dave, and G. L. Wolff. 2002. Maternal methyl supplements in mice affect epigenetic variation and DNA methylation of offspring. J. Nutr. 132:2393S-2400S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duhl, D. M., H. Vrieling, K. A. Miller, G. L. Wolff, and G. S. Barsh. 1994. Neomorphic agouti mutations in obese yellow mice. Nat. Genet. 8:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grunau, C., S. J. Clark, and A. Rosenthal. 2001. Bisulfite genomic sequencing: systematic investigation of critical experimental parameters. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:E65-E66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jablonka, E., and M. J. Lamb. 1989. The inheritance of acquired epigenetic variations. J. Theor. Biol. 139:69-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones, P. A., and S. B. Baylin. 2002. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:415-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, Y. I., I. P. Pogribny, A. G. Basnakian, J. W. Miller, J. Selhub, S. J. James, and J. B. Mason. 1997. Folate deficiency in rats induces DNA strand breaks and hypomethylation within the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65:46-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas, A. 1998. Programming by early nutrition: an experimental approach. J. Nutr. 128:401S-406S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas, A. 1991. Programming by early nutrition in man. Ciba Found. Symp. 156:38-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan, H. D., H. G. Sutherland, D. I. Martin, and E. Whitelaw. 1999. Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 23:314-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nekrutenko, A., and W. H. Li. 2001. Transposable elements are found in a large number of human protein-coding genes. Trends Genet. 17:619-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nigumann, P., K. Redik, K. Matlik, and M. Speek. 2002. Many human genes are transcribed from the antisense promoter of L1 retrotransposon. Genomics 79:628-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petronis, A. 2001. Human morbid genetics revisited: relevance of epigenetics. Trends Genet. 17:142-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rakyan, V. K., M. E. Blewitt, R. Druker, J. I. Preis, and E. Whitelaw. 2002. Metastable epialleles in mammals. Trends Genet. 18:348-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reik, W., W. Dean, and J. Walter. 2001. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science 293:1089-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stover, P. J., and C. Garza. 2002. Bringing individuality to public health recommendations. J. Nutr. 132:2476S-2480S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss, W. M. 2001. Preparation of genomic DNA from mammalian tissue, p. 2.2.1-2.2.3. In F. M. Ausubel et al. (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 1. J. Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Van den Veyver, I. 2002. Genetic effects of methylation diets. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 22:255-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh, C. P., J. R. Chaillet, and T. H. Bestor. 1998. Transcription of IAP endogenous retroviruses is constrained by cytosine methylation. Nat. Genet. 20:116-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waterland, R. A. 2003. Do maternal methyl supplements in mice affect DNA methylation of offspring? J. Nutr. 133:238.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterland, R. A., and C. Garza. 1999. Potential mechanisms of metabolic imprinting that lead to chronic disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 69:179-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitelaw, E., and D. I. Martin. 2001. Retrotransposons as epigenetic mediators of phenotypic variation in mammals. Nat. Genet. 27:361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolff, G. L. 1978. Influence of maternal phenotype on metabolic differentiation of agouti locus mutants in the mouse. Genetics 88:529-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff, G. L. 1996. Variability in gene expression and tumor formation within genetically homogeneous animal populations in bioassays. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 29:176-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolff, G. L., R. L. Kodell, S. R. Moore, and C. A. Cooney. 1998. Maternal epigenetics and methyl supplements affect agouti gene expression in Avy/a mice. FASEB J. 12:949-957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yen, T. T., A. M. Gill, L. G. Frigeri, G. S. Barsh, and G. L. Wolff. 1994. Obesity, diabetes, and neoplasia in yellow A(vy)/− mice: ectopic expression of the agouti gene. FASEB J. 8:479-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoder, J. A., C. P. Walsh, and T. H. Bestor. 1997. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 13:335-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]