Abstract

Resistance to being killed by acidic environments with pH values lower than 3 is an important feature of both pathogenic and nonpathogenic Escherichia coli. The most potent E. coli acid resistance system utilizes two isoforms of glutamate decarboxylase encoded by gadA and gadB and a putative glutamate:γ-aminobutyric acid antiporter encoded by gadC. The gad system is controlled by two repressors (H-NS and CRP), one activator (GadX), one repressor-activator (GadW), and two sigma factors (σS and σ70). In contrast to results of previous reports, we demonstrate that gad transcription can be detected in an hns rpoS mutant strain of E. coli K-12, indicating that gad promoters can be initiated by σ70 in the absence of H-NS.

Commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli must survive transit through the acidic conditions of the stomach, where the pH is normally between 2 and 3, before they can colonize a mammalian host.

The most effective E. coli acid resistance system is dependent upon glutamate and involves two isoforms of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) encoded by gadA and gadB that convert intracellular glutamate to γ-aminobutyrate, consuming one intracellular proton in the reaction. gadB is transcribed in an operon with gadC, which encodes an antiporter that is proposed to import glutamate inside the cell while simultaneously exporting γ-aminobutyrate (9, 15, 20).

The regulation of the gad system is extremely complex. The expression of all of the gad genes is regulated by separate σS-dependent and -independent pathways, despite only one transcriptional start site being identified for each locus (4, 5, 6). The alternate sigma factor, σS, encoded by rpoS, is associated with the stationary-phase expression of gad in cells grown in rich medium, whereas σS-independent regulation occurs in cells grown in minimal-glucose medium.

The levels of expression of the two GAD isoforms and gadC are greatly enhanced in an hns deletion background compared to levels found in wild-type cells of E. coli (6, 17, 24, 25). The histone-like protein H-NS is a major component of the bacterial nucleoid which influences a variety of cellular processes, such as transcription, recombination, and replication (19, 26). The mechanism underlying gene regulation by H-NS is due to either transcriptional silencing through preferential binding to AT-rich curved DNA sequences often found upstream of E. coli promoters or to changes in DNA supercoiling (23, 24). H-NS silencing of gene expression is relieved by environmental signals, such as changes in osmolarity, growth phase, low temperature, anaerobiosis, and pH (2). H-NS has also been implicated in the posttranscriptional regulation of σS expression, as σS accumulation is observed in exponential phase in an hns mutant (3, 23). This suggested that H-NS has an indirect effect on gad expression. However, it has now been shown that H-NS represses gad expression directly (11).

It has been established that the expression of the gad system is mediated by the GadX protein, a member of the AraC/XylS family of transcriptional regulators, encoded by gadX (located downstream of gadA) (10, 13, 17). Expression of gadX is primarily driven by σS (11, 17). GadX was originally shown to play a central role in the H-NS control of genes required in glutamate-dependent acid resistance and to bind to the gadA and gadBC promoters (13, 17). However, repression of the gad genes by H-NS has now been demonstrated to be independent of GadX (11). GadW, another AraC-like regulator, mediates control of the gadA and gadBC genes by repressing gadX and can also activate the gad genes directly in rich medium at pH 8 in stationary phase (11). The cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) represses the system by inhibiting the production of σS. This complex regulatory network maintains tight control over expression of the gad system but also provides flexibility for inducing acid resistance under a variety of conditions that precede exposure to acid.

Transcription of gadA and gadBC in an hns rpoS background.

De Biase et al. (6) have reported that gad transcription is abrogated in an hns rpoS double mutant. They suggest, however, that gad promoters can be recognized by H-NS and transcribed by σ70, as GAD expression driven by multicopy plasmids was not completely shut off in an rpoS mutant. Consistent with this observation, the gad genes are expressed in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (6), which carries a weak rpoS allele with a rare UUG start codon (21). More recently it has been implied that gad expression can be driven by σ70 in cells grown to mid-exponential phase in minimal medium (4).

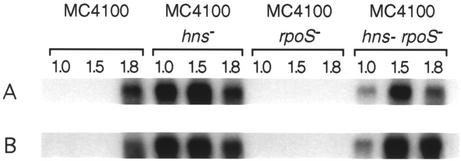

Because of this inconsistency we investigated the expression of the gad genes in isogenic hns (22), rpoS (15), and hns rpoS (23) mutants of E. coli K-12 MC4100 (14) by performing Northern hybridization with the internal fragments of both gadB and gadC (Fig. 1). Due to the high DNA sequence identity (98%) between gadB and its isoform gadA (16), the gadB probe was used to detect the transcripts of both genes. MC4100 is a commonly studied laboratory strain and can be observed to be still undergoing rapid division at an A600 of 1.0 (see Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Northern analysis of gadB and gadC transcription in E. coli MC4100 and isogenic hns, rpoS, and hns rpoS mutants. Total RNA was extracted from cultures of each strain at the growth curve points of A600 of 1.0, 1.5, and 1.8. The membrane was probed with the 32P-labeled internal fragments of gadB (A) and gadC (B).

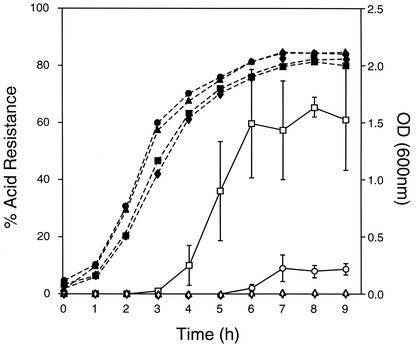

FIG. 2.

Effect of hns mutation on the expression of acid resistance in E. coli MC4100. Cultures were diluted 1:1,000 and were grown in LB medium. Results were taken from a single experiment performed in triplicate. The percentage of acid resistance was determined along the growth curve for strains MC4100 (circles), MC4100 hns (squares), MC4100 rpoS (diamonds), and MC4100 hns rpoS (triangles). Specific acid resistance and optical densities (OD) at 600 nm are indicated by open and closed symbols, respectively.

Total RNA was prepared from cultures grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at various stages of the growth curve (A600 of 1.0, 1.5, and 1.8) by using TRIzol reagent as described by the manufacturers (Gibco) and by 1 h of DNase treatment (Boehringer Mannheim). RNA samples (30 μg) were heated for 5 min at 65°C, fractionated on 1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gels, and blotted onto nylon membranes (Amersham). Membranes were hybridized with the internal fragments of gadB and gadC and were nick translated with [α-32P]deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Amersham).

Primers used for generating the 1.0-kb internal fragment of gadB were 5′ TCC GCT GCA CGA AAT GCG CGA CGA TGT CGC A 3′ and 5′ AAC CTG GTA AGA GGC GTT CTG TAC TTT GGT 3′. Primers used for generating the 1.2-kb internal fragment of gadC were 5′ TCT GGG TCC GAG ATG GGG ATT TGC AGC GAT 3′ and 5′ TGG TGA ACG TCG ACG CGG GTG CAG GAA GAA 3′. PCR amplification was carried out as described previously (20).

Transcripts of all gad genes were absent in the rpoS mutant as well as in the exponentially grown parental strain, whereas transcripts of gad genes were detected in stationary-phase cultures (A600 = 1.8) of the parental strain (Fig. 1). The sizes of the mRNA obtained corresponded to those predicted from the open reading frames of both gadA/B and gadC (data not shown). We also observed a higher-molecular-weight transcript that corresponded with the deduced length of a polycistronic gadBC message, but this transcript was weaker than either the gadA/B or gadC transcript (data not shown). As previously reported by De Biase et al. (6), transcription of the gadA and gadBC genes was strongly enhanced in the hns mutant and occurred during exponential growth.

In contrast to De Biase et al. (6), however, we were able to detect transcripts of both gadA and gadBC in an hns rpoS mutant. The presence of transcripts in an hns rpoS double mutant suggests that the promoters of all gad genes can be recognized by σ70 in vivo. This has been demonstrated for other σS-dependent genes (1, 12, 23). The stronger signal present at an A600 of 1.0 in the hns mutant compared to that of the hns rpoS strain may be explained by the accumulation of σS in mid-exponential phase in this strain (3, 23).

The hns rpoS mutant used in this study was provided by T. Mizuno (Nagoya University), and we have confirmed that it is defective at the rpoS locus as acid resistance can be restored by complementation with the wild-type rpoS gene (data not shown). The detection of gad transcripts in this strain is compatible with the observation of a previous study which showed the expression of transcripts and proteins from other σS-dependent genes (csgBA and hdeAB) in similar E. coli K-12 hns rpoS mutant strains (1).

Possible explanations for the differences between the observations of De Biase et al. (6) and those reported here are the different growth conditions and the strains used in the two studies. De Biase et al. (6) examined a different E. coli K-12 hns rpoS mutant, YK4122, and grew it to early exponential phase for 2 h (A600 = ∼0.4) and to stationary phase for 5 h (A600 = ∼2.1). For stationary-phase induction we grew our cultures overnight for 16 h (A600 = 1.8). It is possible that their incubation times were too short to detect significant levels of gad transcription in this strain. Under these same growth conditions they were only able to detect extremely weak signals of gad transcription in the MC4100 K-12 strain.

Expression of acid resistance in an hns mutant of E. coli.

To determine whether the increased transcriptional expression of the gad genes in hns and hns rpoS mutants correlated with relief of growth phase dependence of acid resistance, the expression of acid resistance was assayed along the growth curve for the isogenic hns, rpoS, and hns rpoS mutants and the wild-type parent of E. coli K-12 grown at 37°C in LB medium (Fig. 2). LB medium for extreme acid exposure (pH 2.5) was adjusted for pH by using HCl. Cultures were adjusted to the appropriate concentrations (1 × 105 to 5 × 105 CFU/ml) by serial dilutions in phosphate-buffered saline, and an aliquot was added to the acidified LB medium and was incubated for 2 h at 37°C with aeration. Control dilutions from the original culture were plated on LB agar and were grown overnight at 37°C. Colony counts were then compared to those obtained from the same culture exposed to the acidified medium to determine the percentage of survival. Acid resistance was defined as the percentage of the number of bacteria surviving the acid treatment compared to the initial number of inoculum exposed. Values shown for percentage of survival represent the mean of a single experiment performed in triplicate.

The hns mutant exhibited induction of acid resistance in mid-exponential phase (A600 = 1.2) some 3 h earlier than the parent strain. This acid resistance was not constitutive and implies that σS is still required for the induction of expression. This finding is supported by the observation that CRP-dependent repression of gadA and gadBC is not relieved in an hns mutant (11), indicating that CRP is a master regulator of glutamate-dependent acid resistance. The hns rpoS double mutant did not exhibit the acid resistance phenotype, reflecting previous observations by De Biase et al. (6). This was despite the fact that we have shown that this strain produces transcripts of gadA and gadBC as well as other acid resistance genes (hdeAB) (20), which are also expressed much earlier in the growth phase by this strain (24). The hns rpoS mutant still expressed GAD enzyme activity when cells were permeabilized with Triton X-100 (data not shown).

A repressing action of H-NS on gadA and gadBC promoters, preventing a successful transcription-inducing complex with σ70 during the exponential growth, can be predicted. In stationary phase the σS levels increase, and this can overcome H-NS repression, probably by more efficient recognition of curved promoter regions required for H-NS binding. The region upstream of many σS-dependent promoters is often AT rich and shows intrinsic DNA curvature (8). Thus, σS may relieve H-NS repression at these promoters. A −10 consensus sequence (CTATACT) was determined for σS-dependent promoters based on the comparison of characteristic promoters known to be under the control of σS and those that can be recognized in vitro by both σS and σ70 (7). Sequences similar to this consensus were identified by primer extension mapping of the transcriptional start points of gadA and gadBC (4, 6).

σS appears to be the major sigma factor used for directing gad transcription for cells grown in complex, but not minimal, medium. Minimal-medium cultures, however, must be able to utilize a different sigma factor under acidic conditions (4). Since only one promoter for each gene appears to be involved regardless of the inducing conditions, the other sigma factor is suggested to be σ70 (4). In accordance with this, a crp gadX gadW mutant which produced no GAD when grown to exponential phase in LB medium made copious amounts of GAD once an hns mutation was introduced (11).

Together these results suggest that additional genes that are likely to be dependent upon σS for their expression contribute to glutamate-dependent acid resistance, a conclusion endorsed in previous reports (5, 6, 18). Some of these reports have also indicated that the gad decarboxylase/antiporter system would create a futile proton cycle, since transport of glutamic acid brings into the cell a proton that is consumed by its decarboxylase (5, 18). To compensate, a mechanism for generating endogenous glutamate would be required. Glutaminases have been previously hypothesized to play a role in glutamate-dependent acid resistance (5). Identification of additional genes and further investigation of the interactions between regulatory components of the gad system will be important for understanding the complex mechanism of glutamate-dependent acid resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Takeshi Mizuno and Chiharu Ueguchi for providing us with MC4100, MC4100 hns, and MC4100 hns rpoS strains. We also thank Joan Slonczweski for providing us with MC4100 rpoS.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the loving memory of Geoff Banks.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnqvist, A., A. Olsen, and S. Normark. 1994. σs-dependent growth-phase induction of the csgBA promoter in Escherichia coli can be achieved in vivo by σ70 in the absence of the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 13:1021-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlung, T., and H. Ingmer. 1997. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 24:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth, M., C. Marschall, A. Muffler, D. Fischer, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1995. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of σS and many σS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:3455-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castanie-Cornet, M. P., and J. W. Foster. 2001. Escherichia coli acid resistance: cAMP receptor protein and a 20 bp cis-acting sequence control pH and stationary phase expression of the gadA and gadBC glutamate decarboxylase genes. Microbiology 147:709-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castanie-Cornet, M. P., T. A. Penfound, D. Smith, J. F. Elliot, and J. W. Foster. 1999. Control of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3525-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Biase, D., A. Tramonti, F. Bossa, and P. Visca. 1999. The response to stationary-phase stress conditions in Escherichia coli: role and regulation of the glutamic acid decarboxylase system. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1198-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinosa-Urgel, M., C. Chamizo, and A. Tormo. 1996. A consensus structure for σs-dependent promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 21:657-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinosa-Urgel, M., and A. Tormo. 1993. σs-dependent promoters in Escherichia coli are located in DNA regions with intrinsic curvature. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3667-3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersch, B. M., F. T. Farooq, D. N. Barstad, D. L. Blankenhorn, and J. L. Slonczweski. 1996. A glutamate-dependent acid resistance gene in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:3978-3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hommais, F., E. Krin, C. Laurent-Winter, O. Soutourina, A. Malpertuy, J. P. Le Caer, A. Danchin, and P. Bertin. 2001. Large-scale monitoring of pleiotropic regulation of gene expression by the prokaryotic nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 40:20-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma, Z., H. Richard, D. L. Tucker, T. Conway, and J. W. Foster. 2002. Collaborative regulation of Escherichia coli glutamate-dependent acid resistance by two AraC-like regulators, GadX and GadW (YhiW). J. Bacteriol. 184:7001-7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robbe-Saule, V., F. Schaeffer, L. Kowarz, and F. Norel. 1997. Relationships between H-NS, σs, SpvR and growth phase in the control of spvR, the regulatory gene in the Salmonella plasmid virulence operon. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:333-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin, S., M. P. Castanie-Cornet, J. W. Foster, J. A. Crawford, C. Brinkley, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. An activator of glutamate decarboxylase genes regulates the expression of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes through control of the plasmid-encoded regulator, Per. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1133-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silhavy, T. J., M. L. Berman, and L. W. Enquist. 1984. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 15.Small, P. L. C., and S. R. Waterman. 1998. Acid stress, anaerobiosis and gadCB: lessons from Lactococcus lactis and Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 6:214-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith, D. K., T. Kassam, B. Singh, and J. F. Elliot. 1992. Escherichia coli has two homologous glutamate decarboxylase genes that map to distant loci. J. Bacteriol. 174:5820-5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tramonti, A., P. Visca, M. De Canio, M. Falconi, and D. De Biase. 2002. Functional characterization and regulation of gadX, a gene encoding an AraC/Xyl-like transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli glutamic acid decarboxylase system. J. Bacteriol. 184:2603-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker, D. L., N. Tucker, and T. Conway. 2002. Gene expression profiling of the pH response in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:6551-6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ussery, D. W., J. C. D. Hinton, B. J. A. M. Jordi, P. E. Granum, A. Seirafi, R. J. Stephen, A. E. Tupper, G. Berridge, J. M. Sidebotham, and C. F. Higgins. 1994. The chromatin-associated protein H-NS. Biochimie 76:968-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waterman, S. R., and P. L. C. Small. 1996. Identification of σs-dependent genes associated with the stationary-phase acid-resistance phenotype of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 21:925-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilmes-Riesenberg, M. R., J. W. Foster, and R. Curtiss III. 1997. An altered rpoS allele contributes to the avirulence of Salmonella typhimurium LT2. Infect. Immun. 65:203-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada, H., T. Yoshida, K.-I. Tanaka, C. Sasakawa, and T. Mizuno. 1991. Molecular analysis of the Escherichia coli hns gene encoding a DNA-binding protein, which preferentially recognizes curved DNA sequences. Mol. Gen. Genet. 230:332-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashino, T., C. Ueguchi, and T. Mizuno. 1995. Quantitative control of the stationary phase-specific sigma factor, σs, in Escherichia coli: involvement of the nucleoid protein H-NS. EMBO J. 14:594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida, T., C. Ueguchi, H. Yamada, and T. Mizuno. 1993. Function of the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein, H-NS: molecular analysis of a subset of proteins whose expression is enhanced in an hns deletion mutant. Mol. Gen. Genet. 237:113-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida, T., T. Yamashino, C. Ueguchi, and T. Mizuno. 1993. Expression of the Escherichia coli dimorphic glutamic acid decarboxylases is regulated by the nucleoid protein H-NS. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57:1568-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, A., S. Rimsky, M. E. Reaban, H. Buc, and M. Belfort. 1996. Escherichia coli protein analogs StpA and H-NS: regulatory loops, similar and disparate effects on nucleic acid dynamics. EMBO J. 15:1340-1349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]