Abstract

Photorhabdus is an insect-pathogenic bacterium in which oral toxicity to insects is found in two distinct taxonomic groups. Using a DNA microarray and comparative genomics, we show that oral toxicity is associated with toxin complex genes tcaABC and that this locus can be mobilized or deleted within different strains.

DNA microarrays have been used to look at the relatedness of strains of bacteria pathogenic to humans (10, 15). Arrays from one strain of bacteria are useful in identifying genes absent, or highly divergent, in unsequenced test strains (15). The data obtained are restricted to the genes present in the reference strain; however, comparisons of the similarity of unknown genomes to the reference strain can be made (6). Further, the presence, absence, or divergence of specific genes can be correlated with phenotypes either shared by, or lacking in, one or another of the strains. Although arrays have been used to study obligate symbionts of insects (1, 2), here we study an insect pathogen.

Photorhabdus bacteria are insect pathogens belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae (11). The bacteria reside in the guts of nematodes that invade insects and are released directly into the open blood system of the insect. They replicate within and kill the insect host (7) by using insecticidal toxins such as the toxin complexes (Tc’s) (20) and the makes caterpillars floppy (Mcf) (5) toxin. Sequencing of different Photorhabdus genomes has confirmed that they contain a wide range of putative virulence factors, including toxins, exoenzymes, and hemolysins (7). We are interested in examining the relatedness of the genomes of orally toxic and nontoxic strains, with specific reference to the genes involved in oral toxicity, the tc genes. The tc genes are members of a large gene family and are found in multiple copies in individual Photorhabdus genomes (20). Four different family members, tca, tcb, tcc, and tcd, have been described on the basis of a description of the first four loci cloned from Photorhabdus luminescens strain W14 (3). Genetic knockout of either tca or tcd greatly reduces the oral toxicity of the resulting supernatant in the associated W14 mutants (3). Here we determine the phylogeny of orally toxic and nontoxic strains via analysis of their 16S DNA sequences (9) in order to test the simplest hypothesis that oral toxicity is found in a single related group of strains. We also hybridize genomic DNA from each strain to a microarray carrying 96 putative virulence factor genes from the orally toxic Photorhabdus strain W14 in order to investigate the minimal subset of tc genes required for oral toxicity.

Oral toxicity is found in two separate groups.

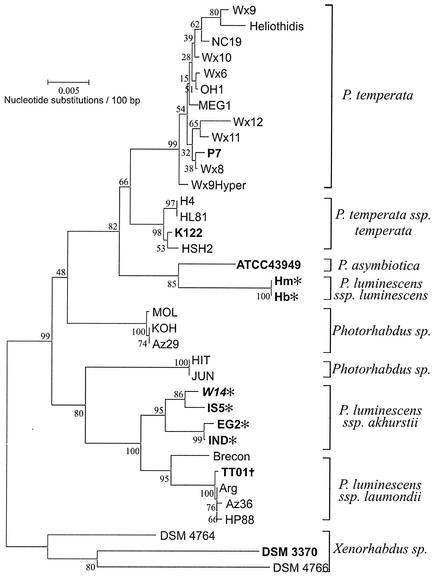

The oral toxicity of the strain supernatants (Table 1) was assessed (19), and the oral toxicity of the washed bacterial cells was examined alongside that of the supernatant itself. Supernatants causing a 50% or greater reduction in growth at 7 days, relative to that in broth-only controls (data not shown), were classed as orally toxic. 16S ribosomal DNA PCR was performed (9), products were sequenced, and a well-supported neighbor-joining tree was constructed (Fig. 1). This phylogeny is very similar to that determined by others using a neighbor-joining method (17). The six orally toxic strains fall into two distinct groups. The first (IS5, EG2, IND, and W14 itself) lies within the previously recognized Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. akhurstii subspecies. The second (Hb1 and Hm1) represents a different subgroup, Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. luminescens. Each of the four nontoxic strains occupies its own independent taxonomic group. This analysis also shows that some other strains do not fit readily within the existing classification (labeled “Photorhabdus sp.” in Fig. 1); however, their likely reclassification is not discussed here.

TABLE 1.

Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus strains, their geographic origins, and their nematode hostsa

| Strain | Origin | Source | Host |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photorhabdus | |||

| Hb | Victoria, Australia | R. Akhurst | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| Hm | Georgia | K. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| W14 | Florida | D. Bowen | Heterorhbditis sp. |

| IND | Antibes | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis indica |

| EG2 | Egypt | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis indica |

| IS5 | Israel | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis indica |

| TT01 | Trinidad | D. Clarke | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora HP88 |

| Brecon | South Australia | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| HP88 | Utah | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora HP88 |

| Az36 | Azores | N. Simoes | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| ARG | Argentina | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| K122 | Ireland | D. Clarke | Heterorhabditis downesi |

| HSH2 | Germany | R. Ehlers | Heterorhabditis megidis |

| HL81 | The Netherlands | F. Galle | Heterorhabditis megidis (NWE) |

| H4 | Hungary | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis megidis |

| Meg1 | Ohio | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis megidis |

| OH1 | Ohio | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis megidis |

| NC19 | North Carolina | R. Akhurst | Heterorhbditis bacteriophora |

| Heliothidis | United States | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| Wx6 | Wisconsin | K. H. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| Wx8 | Wisconsin | K. H. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| P7 | Canada | L. Gerritsen | Heterorhabditis megidis |

| Wx9 | Wisconsin | K. H. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| Wx10 | Wisconsin | K. H. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| Wx11 | Wisconsin | K. H. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| Wx12 | Wisconsin | K. H. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| Wx9Hyper | Wisconsin | K. H. Nealson | Heterorhabditis sp. |

| KOH | Hungary | A. Fodor | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| Az29 | Azores | N. Simoes | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| MOL | Moldavia | L. Gerritsen | Heterorhabditis bacteriophora |

| JUN | The Netherlands | L. Gerritsen | Heterorhabditis megidis |

| HIT | Hungary | C. Griffins | Heterorhabditis “Irish” type |

| ATCC43949 (ASY) | CDC,b Atlanta, Ga. | J. Farmer | Human blood |

| Xenorhabdus | |||

| DSM4766 | Tasmania, Australia | R. Akhurst | Steinernema feltiae |

| DSM3370 (X3) | Georgia | R. Akhurst | Steinernema carpocapsae |

| DSM4764 | Queensland, Australia | R. Akhurst | Steinernema sp. |

FIG. 1.

Phylogeny of Photorhabdus strains (Table 1) highlighting the two groups showing orally toxic culture supernatants. Note that oral toxicity is found in two well-supported subspecies, P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii and P. luminescens subsp luminescens (termed groups 1 and 2). The tree was constructed by using Kimura's two-parameter model of distance estimation and running 1,000 bootstrap replicates with the MEGA program (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis, version 2.1; Arizona State University).

Conserved and variable genes in the array analysis.

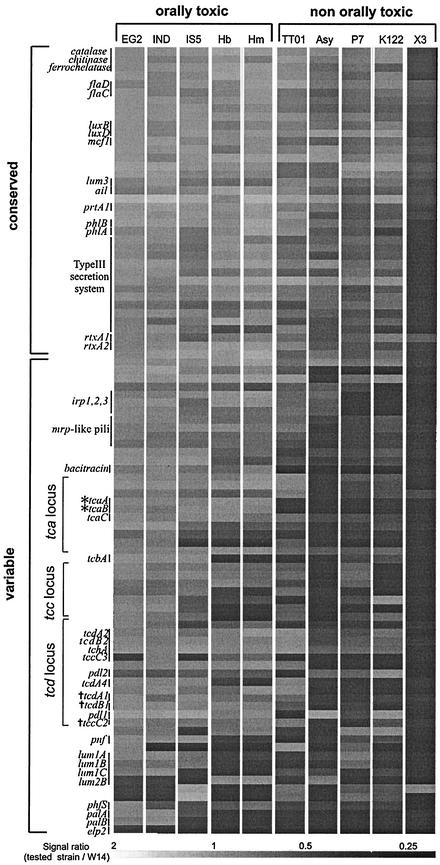

We cohybridized labeled genomic DNA from the nine Photorhabdus test strains with labeled genomic DNA from the control strain, W14, against a 96-gene microarray based on likely virulence factors from the orally toxic strain W14. The genes were divided into those that were “conserved” (values between 2 and 0.5 for all strains) and those that were “variable” (values under 0.5 for some strains) between strains (Fig. 2). Noting the limitations of fixed cutoff points for presence-absence prediction (14) we confirmed the predicted results of the array via sequence data. Only one locus, an erythrocyte lysis protein 2-like gene, appears to be unique to W14, whereas all the other genes occur in one or more of the Photorhabdus strains studied. Thus, the lux genes, producing light, a phenotype common to all Photorhabdus bacteria (12), are found in all strains. A series of putative virulence factors also appear conserved in most or all strains, including the toxin-encoding gene mcf1 (5), rtxA1- and rtxA2-like genes, the operon encoding the prtA protease, and an attachment and invasion locus (ail) homolog (7). The type III secretion system (18), often associated with virulence in other gram-negative bacteria (13), is also present in all strains. Other conserved genes include those encoding catalase, chitinase, ferrochelatase, and flagellae.

FIG.2.

Hybridization ratios for the 96 genes in the W14 array hybridized against the nine Photorhabdus strains and one Xenorhabdus strain. Photorhabdus strains are arranged into those showing orally toxic supernatants and those showing nontoxic supernatants. The 96 W14 genes are arranged into groups predicted to be present (conserved) in most Photorhabdus strains or absent in some strains (variable). Specific groups of genes discussed in the text are labeled. A hybridization ratio of >2 predicts more than one copy of a gene; 0.5 to 2 predicts the presence of a single copy of the gene or a homolog; and <0.5 predicts the absence, or significant sequence divergence, of the gene. A table of gene names, putative functions, and the sequences of the arrayed PCR products is posted at http://staff.bath.ac.uk/bssrffc/downloads.html as supplementary information.

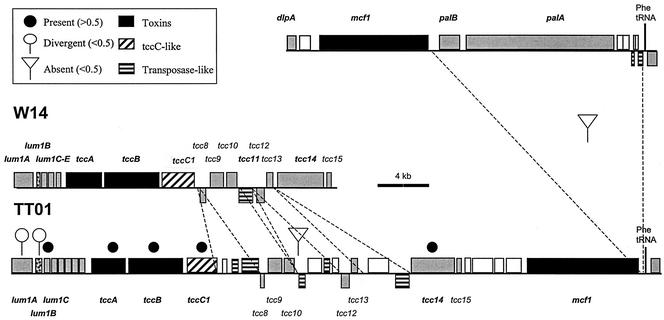

Variable genes include those encoding bacteriocins, toxins and hemolysins, insertion elements, and pili, as well as genes involved in iron acquisition. The lumicins are novel bacteriocins described from Photorhabdus strain W14 (16). The lumicin loci consist of killer protein genes followed by multiple mixed-type immunity genes, whose role is to counter the effect of the killer protein on the host cell. Within W14 there are four predicted loci, lum1, lum2, lum3, and lum4 (16), of which the array predicts lum1 and lum2 to be variable and lum3 to be conserved between strains (Fig. 2). Comparison of the W14 and TT01 lum1 sequences (Fig. 3) shows that while the lum1B E4-type immunity protein gene is conserved between the two strains, the killer protein itself (lum1A) and the lum1C S3-type immunity protein genes are divergent. Divergence in killer protein and immunity protein sequences between strains is expected in the likely presence of intense interstrain competition within the insect host (16).

FIG. 3.

Comparative genomic organization of the region encompassing the lum1 and tcc loci in the different Photorhabdus strains W14 and TT01. Solid circles, open circles, and inverted triangles above the open reading frames indicate the predicted presence, divergence, and absence of genes, respectively, according to hybridization to the microarray. Other symbols and dashed lines indicate the locations of specific deletion or insertion events within the two genomes (see the key). Note that all the genes of the tcc locus are present in both strains and are also linked to the mcf locus in TT01. Sequences are from GenBank accession no. AF346499 and AF503504 and from World Intellectual Property 02/094867.

Some toxin and hemolysin-hemagglutinin genes are also variable between strains. These include the pnf gene, encoding a Photorhabdus necrotizing factor, which is found within a recently acquired region of the W14 genome (18) that is absent from TT01, and the palA and palB genes, encoding a hemolysin-hemagglutinin and its export activator (18). In W14 (Fig. 3), palBA is immediately downstream of the mcf1 toxin gene and adjacent to a Phe tRNA (18), whereas in TT01 (Fig. 3), palBA is deleted from the equivalent location, as predicted. In contrast, a second two-component hemolysin locus, phlAB (4), is predicted to be similar in all strains and indeed to be potentially duplicated in strain Hm. The mrp-like pili and the PhfS fimbrial major subunit gene show a gradual change in hybridization ratio across strains, suggesting that they are present in all strains but may diverge in sequence (18). Finally, the Photorhabdus irp-like genes (8), encoding yersiniabactin biosynthetic protein homologs, predicted to synthesize an iron-scavenging siderophore, are present in all but strains K122 and P7.

Oral toxicity and the tc genes.

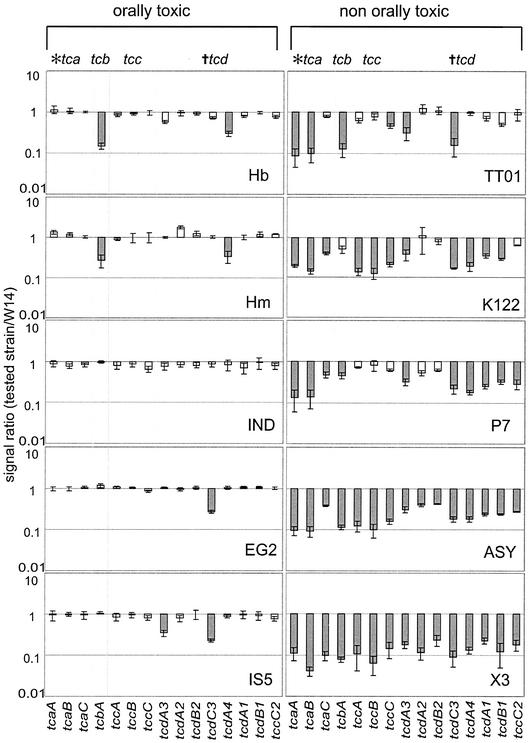

The tc genes are variable genes (Fig. 2) whose distribution is strikingly split between orally toxic and nontoxic strains (Fig. 4). Orally toxic strains carry all three genes in the tca operon (tcaA, tcaB, and tcaC), whereas those lacking toxicity lack tcaA and tcaB. The genes of the tca operon are the only genes to show a perfect correlation with oral toxicity; genes from the tcb, tcc, and tcd operons are all variable across orally toxic strains.

FIG. 4.

Hybridization ratios of genes in the tca, tcb, tcc, and tcd loci for strains with orally toxic (left) or nontoxic (right) supernatants. Values close to 1.0 predict the conservation of a gene between strains (open bars), and values of <0.5 predict its absence or sequence divergence (shaded bars). Note that tcaA and tcaB are the only genes perfectly correlated with the presence of oral toxicity.

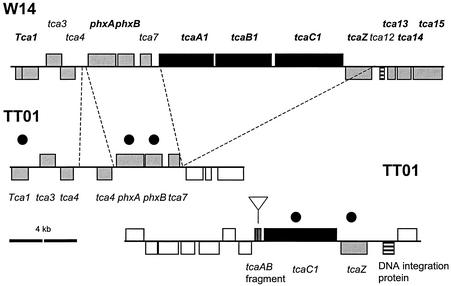

For the tca locus (Fig. 5), a comparison of W14 and TT01 shows two important findings. First, the W14 tcaABC operon is absent from the equivalent location in TT01. Second, a tca-like locus is present elsewhere in TT01 but lacks most of tcaA and tcaB, which have been deleted, and retains only a tcaC1-like gene. These observations confirm that the presence of tcaAB is necessary for the oral toxicity of the bacterial supernatant. Second, the fact that tca-like loci can be found at different locations in different genomes supports the concept that the tca locus is mobile, as suggested by the presence of either a transposase (in W14) or an integration protein (in TT01) adjacent to the tca-like locus (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Comparative genomic organization of the tca locus in the different Photorhabdus strains W14 and TT01. Note that the entire W14 tcaABC operon is deleted from the equivalent location in the TT01 genome but that a tcaC-like gene is found at a different location in the TT01 genome, next to a copy of tcaAB with an internal deletion. This suggests that the tca operon is mobile and can occupy different genomic locations in different strains. See the key in Fig. 3. Sequences are from GenBank accession no. AF346497 and World Intellectual Property 02/094867.

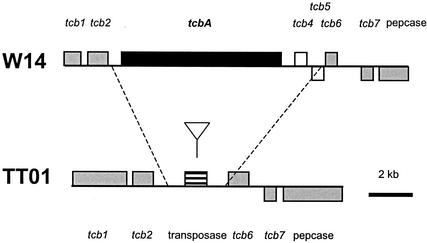

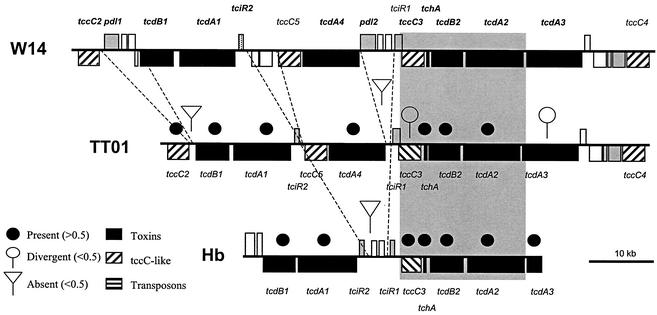

For the tcb locus (Fig. 6), the suggestion that tcbA is lacking from TT01 is again confirmed by analysis of the genomic sequence: tcbA is deleted from the equivalent location in TT01, and a transposase is left in its place. Again comparing W14 and TT01, the array suggests that the tcc locus should be completely conserved, as supported by an examination of the genomic sequence (Fig. 3). Finally, for tcd, the genomic sequence (Fig. 7) confirms that all the tc genes of the island are present in both W14 and TT01, including both lysR-like regulators. Further, the predicted loss of tcdA4 in group 2 orally toxic strains is confirmed by an examination of this locus in the Hb strain. The array even predicts the loss of pdl1 and pdl2 from within the tcd island of TT01, which, again, is confirmed by the sequence (Fig. 7). The localized deletion of tcdA4 and the apparent rearrangements mediated by tccC-like genes support the hypothesis that the tcd genes are encompassed in an unstable pathogenicity island. However, the consistent maintenance of four genetic elements within this island (tcdA2, tcdB2, a gp13-like holin, and the conserved region of tccC3), and the conserved organization of similar tcd-like genes in other bacteria (such as sepA, sepB, orf4, and sepC in Serratia spp.), suggests that these genes form an invariant, but not orally toxic, core.

FIG. 6.

Comparative genomic organization of the tcb locus in the different Photorhabdus strains W14 and TT01. Note that the tcbA gene is deleted from the equivalent location in the genome of TT01 and is replaced by a transposase gene, which is potentially implicated in its excision. See the key in Fig. 3. Sequences are from GenBank accession no. AF346498 and World Intellectual Property 02/094867.

FIG. 7.

Comparative genomic organization of the tcd pathogenicity island in the different Photorhabdus strains W14, TT01, and Hb. Note that despite the presence of local deletions and insertions, W14 and TT01 share all of the tc genes within the tcd locus, whereas strain Hb lacks a tcdA4-like gene, as predicted by the array. The positions of other genes discussed in the text are indicated. Sequences are from GenBank accession no. AY144119 and World Intellectual Property 02/094867 and 99/42589.

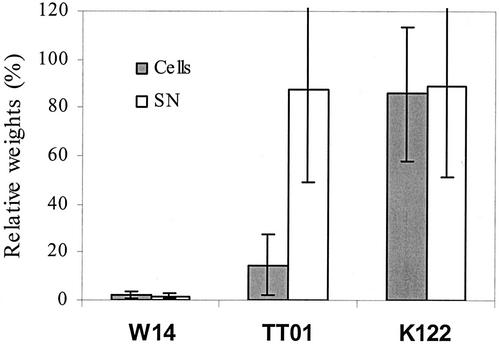

Our previous analysis of strain W14 shows that either tca or tcd can independently contribute to oral toxicity. Thus, plasmid clones of either tca or tcd from W14 confer recombinant oral toxicity when expressed in other, non-orally toxic Photorhabdus strains, such as K122. These data are consistent with the present observation that the presence or absence of tcaAB is perfectly correlated with the toxicity of the supernatant. However, all the tc genes within the tcd island are also present in some strains, such as TT01 (Fig. 7), which lack orally toxic supernatants. To investigate the apparent lack of oral toxicity associated with tcd in TT01, we examined the toxicity of the bacterial cells independently of their supernatant and found that toxicity is associated with the cells rather than the supernatant (Fig. 8). Confirmation that this novel cell-associated toxicity is tcd related now requires knockout or heterologous expression of this locus. In conclusion, even a very limited microarray can provide a powerful predictive tool for correlating observed phenotypes with bacterial genotypes. Similar microarrays may therefore be useful in investigating other Photorhabdus phenotypes involved either in insect pathogenicity or in symbiosis with the nematode hosts of these bacteria.

FIG. 8.

Comparison of the oral toxicity associated with the bacterial supernatant (SN) and that associated with washed bacterial cells, expressed as percentages of weights of untreated controls. Note that cells, but not supernatants, from strain TT01 show oral toxicity, correlating with the presence of genes in the tcd locus. Only strains carrying tcaAB (for example, W14) show orally toxic supernatants.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to R. H. f.-C. from the Exploiting Genomics Initiative of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council of the United Kingdom and by a Marie Curie Ph.D. training grant to J.M. We also acknowledge The Wellcome Trust for funding the Bacterial Microarray Group at St George's Hospital Medical School under its Functional Genomics Resources Initiative.

We thank the laboratories of David Clarke and Stuart Reynolds for useful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akman, L., and S. Aksoy. 2001. A novel application of gene arrays: Escherichia coli array provides insight into the biology of the obligate endosymbiont of tsetse flies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7546-7551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akman, L., R. V. Rio, C. B. Beard, and S. Aksoy. 2001. Genome size determination and coding capacity of Sodalis glossinidius, an enteric symbiont of tsetse flies, as revealed by hybridization to Escherichia coli gene arrays. J. Bacteriol. 183:4517-4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen, D., T. A. Rocheleau, M. Blackburn, O. Andreev, E. Golubeva, R. Bhartia, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 1998. Insecticidal toxins from the bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Science 280:2129-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brillard, J., E. Duchaud, N. Boemare, F. Kunst, and A. Givaudan. 2002. The PhlA hemolysin from the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens belongs to the two-partner secretion family of hemolysins. J. Bacteriol. 184:3871-3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daborn, P. J., N. Waterfield, C. P. Silva, C. P. Y. Au, S. Sharma, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 2002. A single Photorhabdus gene, makes caterpillars floppy (mcf), allows Esherichia coli to persist within and kill insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10742-10747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorrell, N., O. L. Champion, and B. W. Wren. 2002. Application of DNA microarrays for comparative and evolutionary genomics. Methods Microbiol. 33:121-136. [Google Scholar]

- 7.ffrench-Constant, R., N. Waterfield, P. Daborn, S. Joyce, H. Bennett, C. Au, A. Dowling, S. Boundy, S. Reynolds, and D. Clarke. 2003. Photorhabdus: towards a functional genomic analysis of a symbiont and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:433-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ffrench-Constant, R. H., N. Waterfield, V. Burland, N. T. Perna, P. J. Daborn, D. Bowen, and F. R. Blattner. 2000. A genomic sample sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens W14: potential implications for virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3310-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer-Le Saux, M., V. Viallard, B. Brunel, P. Normand, and N. E. Boemare. 1999. Polyphasic classification of the genus Photorhabdus and proposal of new taxa: P. luminescens subsp. luminescens subsp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii subsp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. laumondii subsp. nov., P. temperata sp. nov., P. temperata subsp. temperata subsp. nov., and P. asymbiotica sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1645-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald, J. R., and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evolutionary genomics of pathogenic bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 9:547-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forst, S., B. Dowds, N. Boemare, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp.: bugs that kill bugs. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:47-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forst, S., and K. Nealson. 1996. Molecular biology of the symbiotic-pathogenic bacteria Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus spp. Microbiol. Rev. 60:21-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galan, J. E., and A. Collmer. 1999. Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science 284:1322-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, C. C., E. A. Joyce, K. Chan, and S. Falkow. 2002. Improved analytical methods for microarray-based genome-composition analysis. Genome Biol. 3:RESEARCH0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Ochman, H., and N. A. Moran. 2001. Genes lost and genes found: evolution of bacterial pathogenesis and symbiosis. Science 292:1096-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma, S., N. Waterfield, D. Bowen, T. Rocheleau, L. Holland, R. James, and R. ffrench-Constant. 2002. The lumicins: novel bacteriocins from Photorhabdus luminescens with similarity to uropathogenic-specific protein (USP) from uropathogenic Esherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 24:241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szallas, E., R. Pukall, H. Pamjav, G. Kovaks, Z. Buzas, A. Fodor, and E. Stackebrandt. 2001. Passengers who missed the train: comparative sequence analysis, PhastSystem page RFLP and automated RiboPrint phenotypes of Photorhabdus strains, p. 36-53. In C. Griffin, A. M. Burnell, M. J. Downes, and R. Mulder (ed.), Developments in entomopathogenic nematode/bacterial research. European Commission, Luxembourg.

- 18.Waterfield, N., P. J. Daborn, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 2002. Genomic islands in the insect pathogen Photorhabdus. Trends Microbiol. 10:541-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waterfield, N., A. Dowling, S. Sharma, P. J. Daborn, U. Potter, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 2001. Oral toxicity of Photorhabdus luminescens W14 toxin complexes in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5017-5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waterfield, N. R., D. J. Bowen, J. D. Fetherston, R. D. Perry, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 2001. The toxin complex genes of Photorhabdus: a growing gene family. Trends Microbiol. 9:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]