Abstract

Cadmium and zinc are removed from cells of Ralstonia metallidurans by the CzcCBA efflux pump and by two soft-metal-transporting P-type ATPases, CadA and ZntA. The czcCBA genes are located on plasmid pMOL30, and the cadA and zntA genes are on the bacterial chromosome. Expression of zntA from R. metallidurans in Escherichia coli predominantly mediated resistance to zinc, and expression of cadA predominantly mediated resistance to cadmium. Both transporters decreased the cellular content of zinc or cadmium in this host. In the plasmid-free R. metallidurans strain AE104, single gene deletions of cadA or zntA had only a moderate effect on cadmium and zinc resistance, but zinc resistance decreased 6-fold and cadmium resistance decreased 350-fold in double deletion strains. Neither single nor double gene deletions affected zinc resistance in the presence of czcCBA. In contrast, cadmium resistance of the cadA zntA double mutant could be elevated only partially by the presence of CzcCBA. lacZ reporter gene fusions indicated that expression of cadA was induced by cadmium but not by zinc in R. metallidurans strain AE104. In the absence of the zntA gene, expression of cadA occurred at lower cadmium concentrations and zinc now served as an inducer. In contrast, expression of zntA was induced by both zinc and cadmium, and the induction pattern did not change in the presence or absence of CadA. However, expression of both genes, zntA and cadA, was diminished in the presence of CzcCBA. This indicated that CzcCBA efficiently decreased cytoplasmic cadmium and zinc concentrations. It is discussed whether these data favor a model in which the cations are removed either from the cytoplasm or the periplasm by CzcCBA.

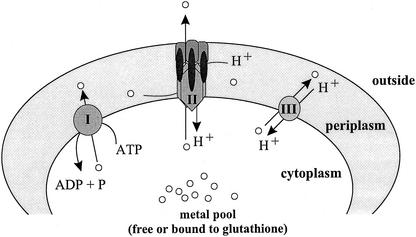

Three different systems mediate efflux of divalent heavy metal cations from bacterial cells: resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND)-driven transenvelope exporters, cation diffusion facilitators (CDF), and P-type ATPases (for a review, see reference 25) (Fig. 1). RND-driven systems are protein complexes able to span the complete cell wall of a gram-negative bacterium. In the case of metal-exporting RND-driven efflux systems, the central pump of this protein complex is usually a member of the RND superfamily (35). In addition, an outer membrane factor and a membrane fusion protein are also required to transport substrate directly to the extracellular medium (25). In contrast, CDF proteins and P-type ATPases are single-subunit transporters. CDF proteins are driven by a chemiosmotic gradient formed by protons or potassium (12, 15), whereas P-type ATPases hydrolyze ATP as their driving force (5). The latter two protein families transport their substrates from the cytoplasm to the periplasm.

FIG. 1.

Prototypes of known efflux systems for zinc and cadmium in R. metallidurans. The Zn2+ and Cd2+ cations are exported from the cytoplasm (free or bound to thiols like glutathione) to the periplasm (grey area) by P-type ATPases (I) or by CDF (III) that are driven by the chemiosmotic gradient. The more complicated RND-driven efflux systems (II) are composed of an RND protein in the cytoplasmic membrane, an outer membrane factor, and a membrane fusion protein. Accordingly to the structures of the RND protein AcrB (21) and the outer membrane factor TolC (14), a trimeric state of all three subunits of the RND-driven efflux complex is assumed. CzcCBA is driven by the proton motive force (H+) (8, 23). The cationic substrates (white circles) may be directly exported out of the cell from the cytoplasm or periplasm (21).

Heavy metal-resistant bacteria harbor a multitude of RND-driven-, CDF-, and P-type-efflux systems (25). Together, they orchestrate a highly efficient network to achieve metal homeostasis, but at this point the role and interdependence of individual efflux pumps are still largely unexplored. An ideal candidate to unravel such a complex interaction of different metal efflux pumps is the β-proteobacterium Ralstonia metallidurans (previously Alcaligenes eutrophus [9]), which contains more efflux pumps than most other sequenced bacteria (25). The wild-type strain CH34 contains two megaplasmids harboring a multitude of metal resistance determinants. The czc determinant (22) on plasmid pMOL30 mediates resistance to Co(II), Zn(II), and Cd(II). It encodes the RND-driven transenvelope exporter CzcCBA composed of the RND protein CzcA, the membrane fusion protein CzcB, and the outer membrane factor CzcC (26, 30). As a second efflux system of this determinant, the CDF protein CzcD is involved in detoxification of the same metals and in regulation of expression of the CzcCBA pump (1, 24). The CzcCBA system forms the outer shell of metal resistance in this bacterium, and its role in cadmium resistance can be successfully described in a virtual model of the R. metallidurans cell (16).

R. metallidurans strain CH34 harbors genes for 10 P-type ATPases, while the related plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum has genes for 4 P-type ATPase (25). Five of these P-type ATPases are putative soft-metal-transporting P-type ATPases (29) showing the typical CPx motif of this protein family. Two of these five CPx-type ATPases are closely related to Cu+/Ag+-transporting ATPases (gene 8627 on contig 709 [g8627/709] and g8785/710), and three are related to Zn2+/Cd2+/Pb2+-transporting proteins (g4648/649, g6751/691, and g6917/692) (25). The pbrA gene (g6917/692) located on plasmid pMOL30, has been characterized as part of the bacterial defense against lead (3). Therefore, PbrA was not included in this study.

With the loss of plasmid pMOL28 and especially of plasmid pMOL30 harboring czc, resistance (MICs) of R. metallidurans to Co(II), Zn(II), and Cd(II) decreases from the millimolar range (5 to 20 mM) in the wild-type strain CH34 to about 200 μM in the plasmid-free strain R. metallidurans AE104 (19). In this study, we further decreased metal resistance of strain AE104 by deletion of the two remaining Zn2+/Cd2+-transporting CPx-type ATPases localized on the bacterial chromosome. The influence of the CzcCBA exporter on metal resistance of these metal-sensitive strains and on transcriptional regulation of the two genes that encode these two CPx-type ATPases implies a highly efficient removal of cations by CzcCBA. Possibly, CzcCBA removes cations directly from the periplasm for export across the outer membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All strains used for experiments were derivatives of the megaplasmid-free R. metallidurans strain AE104 (19). The bacterial strains and the plasmids used and their genotypes are listed in Table 1. Tris-buffered mineral salts medium (19) containing 2 g of sodium gluconate per liter was used to cultivate R. metallidurans strains aerobically with shaking at 30°C. Analytical-grade salts of heavy metal chlorides (with the exception of lead nitrate) were used to prepare 1 M stock solutions, which were sterilized by filtration. Solid Tris-buffered medium contained 20 g of agar per liter.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description or relevant marker | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| R. metallidurans | ||

| AE104 | Plasmid-free | 19 |

| DN438 | ΔcadA | This study |

| DN439 | ΔzntA | This study |

| DN440 | ΔcadA zntA::pLO2 | This study |

| DN441 | ΔzntA cadA::pLO2 | This study |

| DN442 | cadA-lacZ | This study |

| DN443 | cadA-lacZ ΔzntA | This study |

| DN444 | zntA-lacZ | This study |

| DN445 | zntA-lacZ ΔcadA | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| W3110 | Wild type | 10 |

| GG48 | ΔzntA ΔzitB | 10 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pASK3 | E. coli vector | IBA GmbH |

| pLO2 | Vector used for gene interruption | 17 |

| pVDZ′2 | Broad-host-range expression vector | 4 |

| pDNA385 | pVDZ′2::czcCBADRS′ | This study |

| pDNA130 | pVDZ′2::czcCBAD′ | 26 |

Dose-response growth curves.

Dose-response growth curves describing the action of Zn2+ or Cd2+ on Escherichia coli cells were performed in Lennox medium (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, Md.). Genes for the P-type ATPase were cloned under control of the tet promoter on plasmid pASK3 (IBA GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). The medium contained 50 μg of anhydrotetracycline (AHT) to induce expression of these genes. Cultures of E. coli strains grown overnight were used to inoculate parallel cultures with increasing metal concentrations. Cells were cultivated for 16 h with shaking at 37°C, and the optical density was determined at 600 nm.

Induction experiments.

R. metallidurans cells with a lacZ reporter gene fusion were cultivated in Tris-buffered mineral salts medium containing 2 g of sodium gluconate per liter with shaking at 30°C. At a cell density of 70 Klett units, heavy metal salts were added to various final concentrations to the cells, and cells were incubated with shaking for a further 3 h. The specific β-galactosidase activity was determined in permeabilized cells as published previously (24), with 1 U defined as the activity forming 1 nmol of o-nitrophenol per min at 30°C.

Metal ion uptake experiments with E. coli and R. metallidurans. Cells were performed in Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0) by filtration as published previously (27). E. coli cells were cultivated in Tris-buffered mineral salts medium in the presence of 2 g of glucose per liter and 1 g of yeast extract per liter up to 100 Klett units when 200 μg of AHT per liter was added, and incubation was continued with shaking for 3 h at 30°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0). Radioactive metal cations 65Zn2+ (185 GBq/g) or 109Cd2+ (87.4 GBq/g) were added at a concentration of 10 μM, incubation was continued with shaking at 30°C, and the metal content in washed cells (dry weight) was determined at various time points using an equilibration curve. Background binding was not subtracted. R. metallidurans cells were cultivated in Tris medium with sodium gluconate (2 g per liter) instead of glucose to a turbidity of 70 Klett units without yeast extract or AHT. This culture was used directly for metal uptake experiments.

Genetic techniques.

Standard molecular genetic techniques were used (22, 32). For conjugal gene transfer, cultures of donor strain E. coli S17/1 (34) and R. metallidurans recipient strains that had been grown overnight at 30°C in complex medium were mixed (1:1) and plated onto nutrient broth agar. After the bacteria were allowed to grow overnight, they were suspended in saline (9 g of NaCl per liter), diluted, and plated onto selective media as previously described (22). The zntA and cadA genes encoding the two P-type ATPases were amplified from total DNA of the megaplasmid-free strain R. metallidurans AE104. The cadA gene was cloned as a BamHI/XhoI fragment using the primer pair AAA GGA TCC GTT GCT TCC TAT AAA AAA CTT GAC TCT and AAA CTC GAG TGC CGC CTT GAA CTT CAG (restriction endonuclease sites underlined), while zntA was cloned as an EcoRI/BamHI fragment using the primer pair AAA GAA TTC GAA TTT GAC ATG GCT CGC ACC and AAA GGA TCC AAC GGC CTT GCG CGT CA. Both fragments were cloned into the vector plasmid pASK3 (IBA-GmbH).

To construct plasmid pDNA385, the 9-kb EcoRI fragment containing czcCBADRS′ was cloned from plasmid pEC11 (22) into the broad-host-range vector plasmid pVDZ′2 (4) under control of the lac promoter (which is constitutively expressed in R. metallidurans [27]) on this plasmid. The 3′ end of the cloned region contained parts of the coding region for the two-component regulatory system CzcRS that is involved in but not essential for czc regulation (11). The entire gene for the histidine kinase CzcS was not present on the cloned DNA fragment in order to prevent any interference with the constitutive expression of this fragment from the lac promoter of the vector plasmid.

Gene deletions.

The genes were replaced by open reading frames of 24 bp, which were identical to the deleted gene in the first 9 bp and the last 9 bp. This prevented any possible polar effect of the mutation. All replacing open reading frames contained the 6-bp MunI recognition sequence of the restriction endonuclease used to clone in the middle of the open reading frame. The 5′ end of cadA was amplified from total DNA of R. metallidurans strain AE104 as a MunI/NdeI fragment by PCR using the primer pair AAA CAA TTG GGA AGC AAC CAT GAT GCG GAT C and AAA CAT ATG CGG GCT CGG CCA AGC TGT, while the 3′ end was similarly amplified using the primer pair AAA CAA TTG AAG GCG GCA TGA ACA ATG GAT and AAA CAT ATG GGC CTT CCG TTT TGC GCA. For zntA, the primer pair AAC AAT TGG TCA AAT TCC ATT GAT TCT TGT TCC and AAA CAT ATG GAG CTT GGC CGA TTT GCT GTC was used to amplify the 5′ end, while the primer pair AAA CAA TTG AAG GCC GTT TGA CGG CCT G, and AAA CAT ATG TCG ACG AGC TGA TCG GTG TGG was used to amplify the 3′ end. The fragments were cloned into the suicide vector pLO2 (17), sequenced, and used to exchange the target gene against the respective 24-bp open reading frame by recombination as described previously (11). Correct mutations were verified by PCR analysis and Southern DNA-DNA hybridization. This procedure yielded R. metallidurans strains DN438(ΔcadA) and DN439(ΔzntA), which are both derivatives of strain AE104.

Gene insertions.

Gene insertions were constructed for two purposes. First, since it was not possible to construct a ΔcadA ΔzntA strain for unknown reasons, the zntA gene was inactivated in the ΔcadA single deletion strain DN438 by insertion mutagenesis, and the cadA gene was similarly inactivated in the ΔzntA single deletion strain DN439. The central part of the target gene was amplified by PCR from total DNA of strain AE104, cloned as NdeI fragments in plasmid pLO2, and used to interrupt the coding sequence of the target gene as published previously (13). The primer pairs used were AAA CAT ATG CGC ACG CTC ACG GTT CGG and AAA CAT ATG GCC GCT GAC GAT GGT GAC for cadA and AAA CAT ATG GCA AGG GCT GGA TCG CAG and AAA CAT ATG CCA CGC CAT CGG TTT CGG for zntA. This procedure produced the DN438 derivative strain DN440(ΔcadA zntA::pLO2) and the DN439 derivative DN441 (ΔzntA cadA::pLO2).

Second, lacZ was inserted downstream of the target genes to construct an operon fusion. This was done without interrupting any open reading frames downstream of the target genes to prevent polar effects. The 300-bp 3′ end of the zntA gene up to 8 bp downstream of the stop codon was amplified by PCR, and the resulting fragment was cloned into plasmid pLO2 as a SphI/SalI fragment from total DNA of strain AE104 using the primer pair AAA GCA TGC GGC ATG GTC GGT GAC GGT ATC and AAA GTC GAC ACA GGC CGT CAA ACG GCC. Similarly, the 3′ end of the cadA gene was cloned up to 7 bp downstream of the stop codon as a PstI/SalI fragment using AAA CTG CAG GTG GGC ATG GTG GGC GAC and AAA GTC GAC CCA TTG TTC ATG CCG CCT TGA as primers for PCR amplification. After lacZ had been inserted downstream of the two 300-bp fragments, respective operon fusion cassettes were inserted into the open reading frame of the target gene by single crossover recombination. Using this method, cadA-lacZ fusions were constructed in strains AE104 and DN439 (ΔzntA) and zntA-lacZ fusions were constructed in strains AE104 and DN438 (ΔcadA), leading to the four strains (DN442 to DN445) listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Substrate specificity of two chromosomal CPx-type ATPases from R. metallidurans as determined by heterologous expression in E. coli.

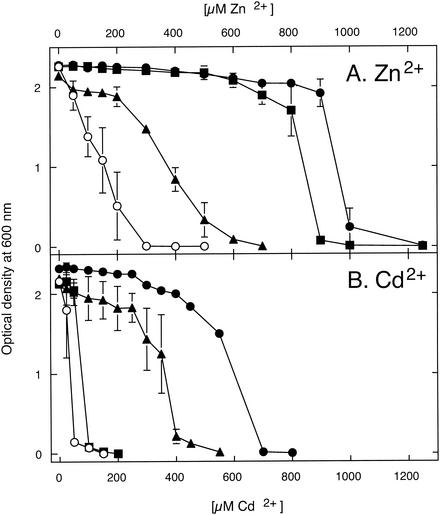

PCR analysis demonstrated that genes encod-ing two putative Cd2+/Zn2+-transporting P-type ATPases (g4648/649 and g6751/691; R. metallidurans sequencing project website [http://www.jgi.doe.gov/JGI_microbial/html/ralstonia/ralston_homepage.html]) were located on the chromosome of R. metallidurans (data not shown). Both genes were amplified by PCR from total DNA of megaplasmid-free R. metallidurans strain AE104 (19) and cloned into plasmid pASK3. The resulting plasmids were transferred into E. coli strain GG48 (ΔzntA ΔzitB), a metal-sensitive strain with deletions in both known Zn2+/Cd2+ efflux systems (ZntA_Ecoli and ZitB_Ecoli) (10). Both genes from R. metallidurans conferred metal resistance in E. coli strain GG48 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Zinc and cadmium resistance of E. coli strains that express P-type ATPases from R. metallidurans. Dose-response curves are shown for E. coli strain GG48(ΔzntA ΔzitB) complemented in trans with genes encoding the R. metallidurans P-type ATPases CadA (g6751/691) (▴) and ZntA (g4648/649) (▪). Both genes were cloned into plasmid pASK3. The negative-control strain is GG48(pASK3) (○), and the positive-control wild-type strain is W3110(pASK3) (•). The means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments are shown.

Half of the maximum inhibition of E. coli strain GG48 (ΔzntA ΔzitB) and wild-type strain W3110 occurred at about 200 μM and 950 μM Zn2+ and at 50 μM and 600 μM Cd2+, respectively (Fig. 2). Complementation in trans with g6751/691 led to half of the maximum inhibition at about 350 μM Zn2+ and the same concentration of Cd2+; this corresponded to a higher degree of cadmium resistance than of zinc resistance in the complemented strain. Therefore, g6751/691 was named cadA. In contrast, the presence of g4648/649 led to a phenotype of near-wild-type zinc resistance (half of the maximum inhibition at about 800 μM) but only to a small increase in cadmium resistance (about 100 μM). Therefore, g4648/649 was named zntA. ZntA, but not CadA, had a minimal (less than twofold) effect on lead resistance in E. coli [lead resistance tested with Pb(II) nitrate] (data not shown).

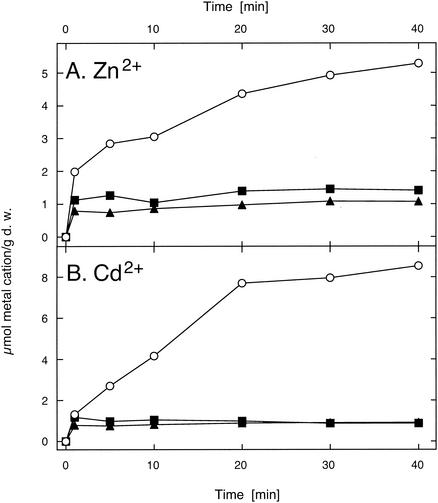

Metal cation uptake into cells of E. coli strain GG48 expressing either one of the P-type ATPase genes from R. metallidurans was examined (Fig. 3). Cells of metal-sensitive E. coli strain GG48 accumulated 5 μmol of 65Zn2+/g (dry weight) or 8 μmol of 109Cd2+/g (dry weight) in an assay buffer containing a 10 μM concentration of either metal cation. Cells expressing either cadA or zntA from R. metallidurans accumulated only 1 μmol of cadmium or zinc/g (dry weight). Thus, both R. metallidurans P-type ATPases were functionally expressed in E. coli and decreased accumulation of cadmium or zinc by E. coli cells.

FIG. 3.

The presence of the CadA and ZntA P-type ATPases from R. metallidurans diminishes the accumulation of Cd2+ and Zn2+ in E. coli strain GG48 in assay buffer containing 10 μM 65Zn2+ (A) or 10 μM 109Cd2+ (B). E. coli strain GG48 (ΔzntA ΔzitB) was complemented in trans with the genes for the R. metallidurans P-type ATPases CadA (g6751/691) (▴) or ZntA (▪). The negative control (○) contained only the vector plasmid pASK3. The accumulation of Cd2+ and Zn2+ is shown in micromoles of the metal cation per gram (dry weight [d. w.]) of cells. The mean values of two independent experiments are shown.

Function of CadA and ZntA in R. metallidurans.

To study the influence of ZntA and CadA on heavy metal resistance in R. metallidurans, both genes were deleted from the chromosome of the megaplasmid-free R. metallidurans strain AE104 (Table 2). Deletion of cadA (strain DN438) led to small decreases in both zinc and cadmium resistance. Deletion of zntA (strain DN439) mainly altered the level of zinc resistance and altered the level of cadmium resistance to a smaller degree.

TABLE 2.

MICs of zinc and cadmium for R. metallidurans strains (megaplasmid-free strain AE104 derivatives) carrying mutations in the genes for P-type ATPasesa

| Bacterial strain and relevant genotype | Complementation in trans | MIC (μM)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn2+ | Cd2+ | ||

| Plasmid-free wild-type | |||

| AE104 | None | 300 | 350 |

| AE104 | pVDZ′2 | 300 | 350 |

| AE104 | pVDZ′2::czcCBAD′ | 12,000 | 3,000 |

| AE104 | pVDZ′2::czcCBADRS′ | 12,000 | 3,000 |

| Single deletions | |||

| DN438 (ΔcadA) | None | 250 | 250 |

| DN438 (ΔcadA) | pVDZ′2::czcCBADRS′ | 12,000 | 3,000 |

| DN439 (ΔzntA) | None | 150 | 300 |

| DN439 (ΔzntA) | pVDZ′2::czcCBADRS′ | 12,000 | 3,000 |

| Double mutations | |||

| DN440 (ΔcadA zntA::pLO2) | None | 50 | 1 |

| DN440 (ΔcadA zntA::pLO2) | pVDZ′2 | 50 | 1 |

| DN440 (ΔcadA zntA::pLO2) | pVDZ′2::czcCBAD′ | 12,000 | 50 |

| DN440 (ΔcadA zntA::pLO2) | pVDZ′2::czcCBADRS′ | 12,000 | 50 |

| DN441 (ΔzntA cadA::pLO2) | None | 50 | 1 |

| DN441 (ΔzntA cadA::pLO2) | pVDZ′2 | 50 | 1 |

| DN441 (ΔzntA cadA::pLO2) | pVDZ′2::czcCBADRS′ | 12,000 | 50 |

The cells were cultivated on Tris-buffered mineral salts medium containing 2 g of sodium gluconate per liter and increasing concentrations of zinc or cadmium chloride. Growth was examined after 3 days at 30°C. The experiment was done twice with identical results.

Additionally, in the ΔcadA or ΔzntA deletion strains, the gene for the respective other P-type ATPase was inactivated by gene disruption (Table 1). The resulting reciprocal strains (DN440 and DN441) displayed the same degree of decreased zinc and cadmium resistance (Table 2). Cadmium tolerance of both double mutant strains decreased more than 1,000-fold from that of the R. metallidurans wild-type strain CH34(pMOL28, pMOL30), which harbors the complete set of cadmium detoxification systems (19). In contrast to the strong effect on cadmium resistance and the significant effect on zinc resistance, the double deletion or either single deletion did not affect lead resistance of R. metallidurans (data not shown).

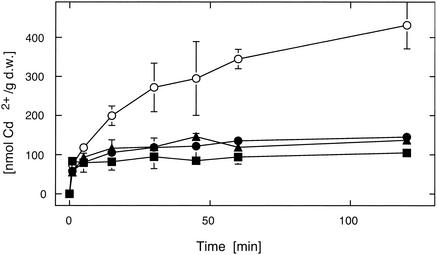

R. metallidurans cells without CadA and ZntA accumulated more Cd2+ than the respective control cells (Fig. 4) (65Zn2+ is no longer available and could not be tested). This demonstrated that resistance mediated by both P-type ATPases is based on diminished cation accumulation. The R. metallidurans double deletion strain accumulated 431 nmol of 109Cd2+/g (dry weight) in medium with 1 μM 109Cd(II), while the single deletion strains and the positive-control strain AE104 accumulated between 105 and 145 nmol/g (dry weight) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Uptake of cadmium by R. metallidurans strains with mutations in the genes for CPx-type ATPases. Uptake of 1 μM 109Cd2+ by cells of the megaplasmid-free R. metallidurans strain AE104 (•), its ΔzntA deletion derivative DN439 (▴), its ΔcadA deletion derivative DN438 (▪), and the ΔzntA cadA::pLO2 double mutant strain DN441 (○) is compared. Uptake is measured in nanomoles of Cd2+ per gram (dry weight [d.w.]) of cells.

Regulation of cadA and zntA expression in R. metallidurans.

As suggested, the substrate specificities of ZntA or CadA after heterologous expression in E. coli may indicate that both proteins have rather distinct functions. Such a specialization should also be mirrored by the expression profiles of both genes in R. metallidurans. Expression was studied by an operon fusion of zntA or cadA with a promoterless lacZ gene, which was inserted by homologous recombination directly downstream of the gene. Neither gene was inactivated by this insertion, shown by PCR and DNA sequence analysis of the modified gene regions (data not shown). The gene for a putative lipoprotein signal peptidase (g6752/691) directly downstream of cadA was not disturbed by the lacZ insertion (data not shown). Since zntA is flanked by open reading frames only on the other DNA strand, no polar effects should have been generated when lacZ was inserted.

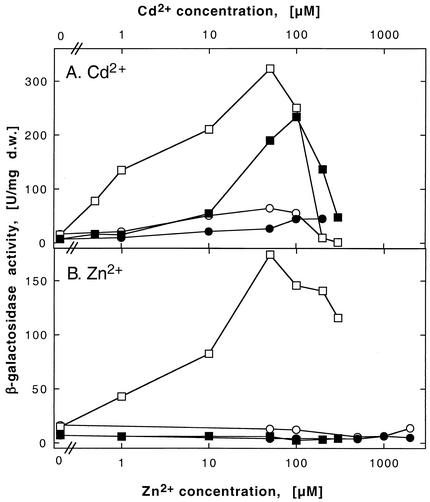

Expression of zntA and cadA was induced by cadmium (Fig. 5A and Fig. 6A). Expression of zntA was enhanced 20-fold after induction with 100 μM Cd2+. Expression of cadA was slightly greater (50-fold) at the same cadmium concentration. Thus, both proteins may be synthesized in vivo to export cadmium. In contrast, expression levels of both genes responded differently to increasing zinc concentrations: while zntA was induced by Zn2+ to a degree similar to that induced by Cd2+ (Fig. 5), cadA was not induced by Zn2+ when ZntA was present (Fig. 6B). Thus, expression of zntA and transport activity of ZntA in vivo seem to be sufficient to protect cells of R. metallidurans strain AE104 against environmental zinc concentrations up to 100 μM, while CadA seemed to be relevant in vivo as an additional system for cadmium efflux.

FIG. 5.

Induction of a zntA-lacZ operon fusion by heavy metal cations in various R. metallidurans strains. The bacterial strains were DN444 (zntA-lacZ) (closed symbols) and DN445 (zntA-lacZ ΔcadA) (open symbols). Moreover, these strains were left alone (squares) or complemented in trans with czcCBADRS′ on plasmid pDNA385 (circles). The respective negative vector controls (plasmid pVDZ′2 only) gave results similar to the plasmid-free strains and are not shown. β-Galactosidase activity is measured in units per milligram (dry weight [d.w.]).

FIG. 6.

Induction of a cadA-lacZ operon fusion by heavy metal cations in various R. metallidurans strains. The bacterial strains were DN442 (cadA-lacZ) (closed symbols) and DN443 (cadA-lacZ ΔzntA) (open symbols). Moreover, these strains were left alone (squares) or complemented in trans with czcCBADRS′ on plasmid pDNA385 (circles). The respective negative vector controls (plasmid pVDZ′2 only) gave results similar to the plasmid-free strains and are not shown. β-Galactosidase activity is measured in units per milligram (dry weight [d.w.]).

To study the influence of ZntA on the expression of CadA and vice versa, cadA-lacZ ΔzntA and zntA-lacZ ΔcadA strains were constructed. Moreover, this allowed the determination of the effects of other metal cations on the expression of either gene. Neither cobalt (100 μM), Cu2+ (250 μM), nor lead nitrate (250 μM) induced zntA-lacZ in the ΔcadA mutant strain (1.2 ± 0.2-fold, 0.6 ± 0.2-fold, and 1.0 ± 0.4-fold induction, respectively [means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments]) or induced cadA-lacZ in the ΔzntA strain (0.8 ± 0.2-fold, 0.5 ± 0.2-fold, and 1.2 ± 0.1-fold induction, respectively). Nickel (100 μM) did not induce cadA-lacZ ΔzntA (1.6 ± 0.6-fold) and induced zntA-lacZ ΔcadA only slightly (1.9 ± 0.1-fold induction). Resistance to any of the four cations was not affected in the double deletion strains (data not shown). This indicated that both CadA and ZntA are specifically involved in zinc or cadmium homeostasis in R. metallidurans.

The presence or absence of CadA did not change the expression profile of zntA in response to increasing zinc or cadmium concentrations (Fig. 5). In contrast, expression of cadA could be induced by zinc only in the absence of ZntA (Fig. 6). Expression of cadA by cadmium in the absence of ZntA showed optimal induction at 50 μM Cd2+, resulting in a 25-fold induction (Fig. 6A). Moreover, cadA was induced by cadmium concentrations lower than 50 μM to a larger extent in the absence of ZntA than in its presence. In all four strains, expression levels of the operon fusions were low after induction with 200 or 300 μM Cd2+, probably due to toxic effects of cadmium. This showed the importance of transcriptional regulation of cadA and zntA for the assignment of the physiological function of either protein: while ZntA mediates homeostasis of both zinc and cadmium, CadA functions in vivo only in the export of cadmium.

CzcCBA fails to complement cadmium sensitivity of zntA cadA double knock-out strains.

To gain insight into the complexity of efflux systems in R. metallidurans, the interplay of the ZntA/CadA system on one hand and the CzcCBA/CzcD export system on the other hand was analyzed. Plasmid pDNA385 contained the czcCBADRS′ region of the czc determinant cloned under control of the constitutive lac promoter. This plasmid was transferred into R. metallidurans strain AE104 and its mutant derivatives, and the influence of CzcCBA/CzcD on metal resistance was studied (Table 2). The presence of ZntA alone (ΔcadA deletion strain in comparison to double deletion strains) increased zinc resistance in R. metallidurans fivefold, the presence of CadA alone increased resistance threefold, and the presence of both CadA and ZntA increased resistance sixfold (strain AE104). However, the presence of CzcCBA/CzcD increased zinc resistance 240-fold, independent of the presence of either P-type ATPase. Thus, zinc is efficiently exported by the Czc system before toxic concentrations are reached that require the action of a P-type ATPase.

In contrast, the P-type ATPases were more important for cadmium resistance than for zinc resistance (Table 2). The presence of CadA alone increased cadmium resistance 300-fold, the presence of ZntA increased resistance 250-fold, and the presence of both increased resistance 350-fold. However, expression of the Czc system in the absence of both ATPases increased cadmium resistance only 50-fold. At least one P-type ATPase was required to reach full resistance, a 3,000-fold increase. This indicated that R. metallidurans needs both CzcCBA and at least one P-type ATPase for an effective detoxification of cadmium. On the other hand, zinc can be removed sufficiently by the action of CzcCBA alone.

Influence of the CzcCBA/CzcD system on induction of zntA and cadA.

The presence of CzcCBA/CzcD strongly decreased induction of either P-type ATPase by cadmium (Fig. 4 and 5). Moreover, neither cadA (in a ΔzntA strain) nor zntA could be induced by Zn2+ in the presence of CzcCBA/CzcD, not even at metal concentrations above the MIC of cells that did not possess the Czc system. This clearly indicated that the action of CzcCBA/CzcD in the cell diminished concentrations of cadmium and zinc below the threshold levels required for P-type ATPase gene expression.

Expression of the two P-type ATPase-encoding genes was also examined in the presence of plasmid pDNA130, which carries the czcCBA operon and a truncated, inactive czcD′ gene. Metal resistance conferred by czcCBAD′ to strain AE104 and to a cadA zntA double mutant strain was identical to resistance conferred by czcCBADRS′ (Table 2). Moreover, czcCBAD′ and czcCBADRS′ yielded similar results when induction of zntA-lacZ in the presence and absence of cadA and induction of cadA-lacZ in the presence and absence of zntA by cadmium or zinc was determined (data not shown). Therefore, CzcCBA was responsible for the observed effects of the czcCBADRS′ region on metal resistance and regulation of znt or cadA expression, and the influence of CzcD could be ignored.

DISCUSSION

The presence of CzcCBA inhibits induction of cadA and zntA by zinc and cadmium.

R. metallidurans harbors three known efflux systems that are induced by zinc and cadmium, the czc system on plasmid pMOL30 (16) and the two CPx-type ATPase-encoding genes cadA and zntA located on the bacterial chromosome (Fig. 1). The presence of the CzcCBA efflux complex yields the largest increase in zinc and cadmium resistance (16) and prevented induction of zntA or cadA by either metal. Thus, CzcCBA removes Zn2+ and Cd2+ very efficiently, and high expression levels of zntA and of cadA are not needed for additional detoxification.

The main difference between induction of cadA and zntA by zinc was visible in the presence of the other P-type ATPase: induction of cadA by zinc was completely inhibited by the presence of either CzcCBA or ZntA (Fig. 6B), while induction of zntA by zinc was inhibited by CzcCBA but not by CadA (Fig. 5B). This yielded the rank order of CzcCBA > ZntA > CadA for zinc detoxification, while all three systems seemed to be required for full cadmium resistance.

Expression of the genes for CPx-type ATPases are usually regulated by cytoplasmic components.

Since zntA and cadA are induced by heavy metals, regulators for both genes probably exist. The identities of these regulators are unknown, but the genes for soft-metal-transporting ATPases are usually regulated by a repressor belonging to the MerR or ArsR-SmtB family of proteins (31). These proteins bind the inducing cations with high affinity to cysteine residues and interact directly with the promoter or operator region of the ATPase-encoding gene. In the case of MerR-type regulators, the protein is sitting directly at the promoter, exerting negative control, until the inducing metal binds (18). Therefore, expression of cadA and zntA in R. metallidurans is probably controlled by the cytoplasmic concentration of zinc and cadmium in the bacterial cell.

CzcCBA decreases the cytoplasmic concentrations of zinc and cadmium very efficiently.

Since constitutive expression of czcCBA prevents induction of cadA or zntA by Zn2+ or Cd2+, and these two CPx-type ATPase-encoding genes are probably regulated by cytoplasmic components, CzcCBA seems to be able to decrease the cytoplasmic concentrations of zinc and cadmium very efficiently.

The RND protein AcrB, which is related to CzcA, contains vestibules in the trimeric protein that link the central cavity to the periplasm (21), so the structure of RND proteins may allow direct periplasmic access. The periplasmic headpieces of RND proteins exporting organic molecules define the substrate range of the corresponding RND-driven efflux complex (summarized in reference 25), and methionine residues in the headpiece of the copper-exporting RND protein CusA from E. coli are essential for copper export of the CusCBA complex (6). Despite all efforts, no cytoplasmic binding sites for substrate cations could be identified in CzcA (7; K. Helbig, A. Legatzki, and D. H. Nies, unpublished data). Thus, the substrate-binding sites of RND-driven efflux systems seem to be located in the periplasmic headpiece of the RND pump protein. This may imply access of substrates from the periplasm in addition to access from the cytoplasm or cytoplasmic membrane, as suggested previously (21). That way, cations would be prevented from entering the cytoplasm at an early stage of the cellular metal uptake process, which may explain the high efficiency of metal detoxification by RND-driven efflux systems like CzcCBA.

Function of the two P-type ATPases.

Despite this high efficiency of metal detoxification by CzcCBA, at least one of the two P-type ATPases is essential for full cadmium resistance in R. metallidurans. This shows that cadmium (much more than zinc) seems to some degree to be able to escape metal removal by the CzcCBA system. Since CzcA was not able to transport metal cations in vitro in the presence of glutathione (D. H. Nies, unpublished data), binding of cytoplasmic cadmium to cellular thiol compounds may prevent their removal by CzcCBA. On the other hand, P-type ATPases seem to accept metals from thiolate complexes as their true substrate in vivo (33). Since cadmium has a higher affinity for thiolates than zinc does, this could be one reason for the importance of P-type ATPases in R. metallidurans metal homeostasis.

Zinc, with its lower affinity to thiolates, could be sufficiently detoxified by CzcCBA alone. Therefore, what is the use of ZntA as an additional system? When the three CPx-type ATPases of R. metallidurans, PbrA, CadA, and ZntA, were compared, some interesting differences were observed (data not shown). PbrA (798 amino acids [aa]) resembles the first described member of this group of CPx-type ATPases, i.e., CadA (727 aa) from Staphylococcus aureus (28), in size and overall structure. ZntA and CadA from R. metallidurans, on the other hand, are different from these two proteins and from each other. CadA from R. metallidurans has a unique size; due to a very long amino terminus, it has a total of 984 aa. ZntA (784 aa), although similar in size to PbrA, contains an interesting histidine-rich amino terminus: the region from aa 20 to 55 exhibits 16 histidine residues, mostly separated by G, P, or charged amino acid residues.

The amino-terminal portion of CPx-type ATPases is not essential for transport (20), but it may regulate transport activity (2). This is even more important for ZntA than for CadA, because zinc is an essential trace element and complete depletion of the cytoplasmic zinc pool has to be prevented. Thus, ZntA from R. metallidurans may be able to export zinc only if sufficient amounts of this cation are bound to the amino-terminal histidine residues of the protein, making it a highly specific detoxification system for zinc cations in vivo.

In summary, zinc and cadmium are predominantly detoxified in R. metallidurans by the CzcCBA efflux system, which exports these cations from the periplasm and/or from the cytoplasm directly into the extracellular medium. The two CPx-type ATPases ZntA and CadA may be required to export cations bound to thiolate complexes (not the thiolate complexes) into the periplasm (for further export by CzcCBA?). Transport activity of ZntA may be carefully regulated by a zinc-sensing site at the amino terminus of the protein to prevent depletion of the anabolic zinc pool, essential for synthesis of zinc-containing proteins and growth. CadA, on the other hand, may be the main detoxification system for cadmium thiolate complexes and may serve as the final backup system for zinc resistance. Possibly, it is this fine-tuning of different metal transporters that allows R. metallidurans to survive in environments highly polluted with heavy metals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Hatch project 136713, NIEHS grant ESO4940, and funds from EPA to C.R. and grant Ni262/3-3 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie to D.H.N.

Preliminary genomic sequence data for R. metallidurans were obtained from the DOE Joint-Genome Institute (JGI) R. metallidurans sequencing project website. We thank Grit Schleuder for skillful technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anton, A., C. Groβe, J. Reiβman, T. Pribyl, and D. H. Nies. 1999. CzcD is a heavy metal ion transporter involved in regulation of heavy metal resistance in Ralstonia sp. strain CH34. J. Bacteriol. 181:6876-6881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal, N., E. Mintz, F. Guillain, and P. Catty. 2001. A possible regulatory role for the metal-binding domain of CadA, the Listeria monocytogenes Cd2+-ATPase. FEBS Lett. 506:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borremans, B., J. L. Hobman, A. Provoost, N. L. Brown, and D. Van der Lelie. 2001. Cloning and functional analysis of the pbr lead resistance determinant of Ralstonia metallidurans CH34. J. Bacteriol. 183:5651-5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deretic, V., S. Chandrasekharappa, J. F. Gill, D. K. Chatterjee, and A. Chakrabarty. 1987. A set of cassettes and improved vectors for genetic and biochemical characterization of Pseudomonas genes. Gene 57:61-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagan, M. J., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1994. P-type ATPases of eukaryotes and bacteria: sequence comparisons and construction of phylogenetic trees. J. Mol. Evol. 38:57-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke, S., G. Grass, C. Rensing, and D. H. Nies. 2003. Molecular analysis of the copper-transporting CusCFBA efflux system from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:3804-3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg, M. 2000. Reinigung und aktive Rekonstitution von CzcA, einem Mitglied der RND-Proteinfamilie. Dissertation. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany.

- 8.Goldberg, M., T. Pribyl, S. Juhnke, and D. H. Nies. 1999. Energetics and topology of CzcA, a cation/proton antiporter of the RND protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26065-26070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goris, J., P. De Vos, T. Coenye, B. Hoste, D. Janssens, H. Brim, L. Diels, M. Mergeay, K. Kersters, and P. Vandamme. 2001. Classification of metal-resistant bacteria from industrial biotopes as Ralstonia campinensis sp. nov., Ralstonia metallidurans sp. nov. and Ralstonia basilensis Steinle et al. 1998 emend. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1773-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grass, G., B. Fan, B. P. Rosen, S. Franke, D. H. Nies, and C. Rensing. 2001. ZitB (YbgR), a member of the cation diffusion facilitator family, is an additional zinc transporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:4664-4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Große, C., G. Grass, A. Anton, S. Franke, A. Navarrete Santos, B. Lawley, N. L. Brown, and D. H. Nies. 1999. Transcriptional organization of the czc heavy metal homoeostasis determinant from Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 181:2385-2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guffanti, A. A., Y. Wei, S. V. Rood, and T. A. Krulwich. 2002. An antiport mechanism for a member of the cation diffusion facilitator family: divalent cations efflux in exchange for K+ and H+. Mol. Microbiol. 45:145-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juhnke, S., N. Peitzsch, N. Hübener, C. Groβe, and D. H. Nies. 2002. New genes involved in chromate resistance in Ralstonia metallidurans strain CH34. Arch. Microbiol. 179:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koronakis, V., A. Sharff, E. Koronakis, B. Luisi, and C. Hughes. 2000. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature 405:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, S. M., G. Grass, C. J. Haney, B. Fan, B. P. Rosen, A. Anton, D. H. Nies, and C. Rensing. 2002. Functional analysis of the Escherichia coli zinc transporter ZitB. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legatzki, A., S. Franke, S. Lucke, T. Hoffmann, A. Anton, D. Neumann, and D. H. Nies. 2003. First step towards a quantitative model describing Czc-mediated heavy metal resistance in Ralstonia metallidurans. Biodegradation 14:153-168. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lenz, O., E. Schwartz, J. Dernedde, T. Eitinger, and B. Friedrich. 1994. The Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 hoxX gene participates in hydrogenase regulation. J. Bacteriol. 176:4385-4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livrelli, V., I. W. Lee, and A. O. Summers. 1993. In vivo DNA-protein interactions at the divergent mercury resistance (mer) promoters. I. Metalloregulatory protein MerR mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 268:2623-2631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mergeay, M., D. Nies, H. G. Schlegel, J. Gerits, P. Charles, and F. van Gijsegem. 1985. Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 is a facultative chemolithotroph with plasmid-bound resistance to heavy metals. J. Bacteriol. 162:328-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitra, B., and R. Sharma. 2001. The cysteine-rich amino-terminal domain of ZntA, a Pb(II)/Zn(II)/Cd(II)-translocating ATPase from Escherichia coli, is not essential for its function. Biochemistry 40:7694-7699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami, S., R. Nakashima, R. Yamashita, and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. Crystal structure of bacterial multidrug efflux transporter AcrB. Nature 419:587-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nies, D., M. Mergeay, B. Friedrich, and H. G. Schlegel. 1987. Cloning of plasmid genes encoding resistance to cadmium, zinc, and cobalt in Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34. J. Bacteriol. 169:4865-4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nies, D. H. 1995. The cobalt, zinc, and cadmium efflux system CzcABC from Alcaligenes eutrophus functions as a cation-proton-antiporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:2707-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nies, D. H. 1992. CzcR and CzcD, gene products affecting regulation of resistance to cobalt, zinc, and cadmium (czc system) in Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 174:8102-8110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nies, D. H. 2003. Efflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:313-339. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Nies, D. H., A. Nies, L. Chu, and S. Silver. 1989. Expression and nucleotide sequence of a plasmid-determined divalent cation efflux system from Alcaligenes eutrophus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:7351-7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nies, D. H., and S. Silver. 1989. Plasmid-determined inducible efflux is responsible for resistance to cadmium, zinc, and cobalt in Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 171:896-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nucifora, G., L. Chu, T. K. Misra, and S. Silver. 1989. Cadmium resistance from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258 cadA gene results from a cadmium-efflux ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3544-3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rensing, C., M. Ghosh, and B. P. Rosen. 1999. Families of soft-metal-ion-transporting ATPases. J. Bacteriol. 181:5891-5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rensing, C., T. Pribyl, and D. H. Nies. 1997. New functions for the three subunits of the CzcCBA cation-proton antiporter. J. Bacteriol. 179:6871-6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson, N. J., S. K. Whitehall, and J. S. Cavet. 2001. Microbial metallothioneins. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 44:183-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Sharma, R., C. Rensing, B. P. Rosen, and B. Mitra. 2000. The ATP hydrolytic activity of purified ZntA, a Pb(II)/Cd(II)/Zn(II)-translocating ATPase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3873-3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tseng, T.-T., K. S. Gratwick, J. Kollman, D. Park, D. H. Nies, A. Goffeau, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1999. The RND superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:107-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]