Abstract

TraG-like proteins are essential components of type IV secretion systems. During secretion, TraG is thought to translocate defined substrates through the inner cell membrane. The energy for this transport is presumably delivered by its potential nucleotide hydrolase (NTPase) activity. TraG of conjugative plasmid RP4 is a membrane-anchored oligomer that binds RP4 relaxase and DNA. TrwB (R388) is a hexameric TraG-like protein that binds ATP. Both proteins, however, lack NTPase activity under in vitro conditions. We characterized derivatives of TraG and TrwB truncated by the N-terminal membrane anchor (TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1) and/or containing a point mutation at the putative nucleotide-binding site (TraGΔ2K187T and TraGK187T). Unlike TraG and TrwB, truncated derivatives behaved as monomers without the tendency to form oligomers or aggregates. Surface plasmon resonance analysis with immobilized relaxase showed that mutant TraGK187T was as good a binding partner as the wild-type protein, whereas truncated TraG monomers were unable to bind relaxase. TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 bound ATP and, with similar affinity, ADP. Binding of ATP and ADP was strongly inhibited by the presence of Mg2+ or single-stranded DNA and was competed for by other nucleotides. Compared to the activity of TraGΔ2, the ATP- and ADP-binding activity of the point mutation derivative TraGΔ2K187T was significantly reduced. Each TraG derivative bound DNA with an affinity similar to that of the native protein. DNA binding was inhibited or competed for by ATP, ADP, and, most prominently, Mg2+. Thus, both nucleotide binding and DNA binding were sensitive to Mg2+ and were competitive with respect to each other.

Type IV secretion is an energy-driven mechanism for delivery of effector molecules from bacterial donors to recipient cells. It mediates the transfer of toxic components into eukaryotic hosts by many pathogenic bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, Legionella pneumophila, Brucella spp., and Bartonella henselae and enables DNA transfer in bacterial conjugation systems such as that encoded by plasmid RP4.

A set of genes is conserved among type IV secretion systems (T4SS). Most of these genes are responsible for the formation of a membrane-spanning protein complex and for biosynthesis of a pilus (8). In bacterial conjugation systems the pilus acts as a sex pilus that is required for initial attachment to recipient cells, followed by mating pair formation and DNA transfer (45). An additional component conserved among T4SS is the TraG-like protein (coupling protein). TraG is a putative nucleoside triphosphatase (NTPase) that may serve as the active motor for secretion. It forms a membrane-anchored oligomer (1, 22, 38), which binds to DNA nonspecifically (27, 29, 38) and is involved in recognition of the substrate to be secreted (10, 38). In the case of the conjugative plasmid RP4, this substrate consists of the plasmid-encoded protein relaxase (TraI) that is covalently attached to the linearized transfer DNA strand of the plasmid (32). The cytoplasmic domain of the TraG-like protein of plasmid R388, TrwBΔN70, has a hexameric pore-like structure that probably extends into the membrane (13), indicating that TraG-like proteins may serve as a gate through the inner membrane. In vitro studies with purified TraG-like proteins TrwB (R388), TraG (RP4), TraD (F), and HP0524 (H. pylori) failed to confirm the postulated NTPase activity (27, 38). However, it was demonstrated that TrwB binds ATP (16, 27).

In the present work, the nucleotide-binding properties of TraG and TrwB were studied in detail and the multiple activities of TraG and TrwB were dissected structurally and functionally. To this end, deletion mutation and point mutation derivatives were purified and biochemically characterized. Apart from binding DNA and ATP, the cytoplasmic domains of TraG and of TrwB were also found to bind ADP. DNA binding and nucleotide binding were competitive with each other and were both inhibited by Mg2+. Other nucleotides (GTP, CTP, UTP, and dTTP) were shown to be effective in competing for ATP binding. A point mutation at conserved residue K187 of the proposed P-loop motif (Walker A motif) of TraG caused a significant decrease in nucleotide-binding ability. Removal of the membrane anchor of TraG and TrwB prevented oligomerization or aggregation. Furthermore, the affinity of TraG for relaxase (TraI) was lost.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Escherichia coli strains SCS1 (Stratagene), HB101 (5) and HB101 Nxr (spontaneously nalidixic acid resistant derivative of HB101) were grown in YT medium (25) buffered with 25 mM 3(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (pH 8.0). When appropriate, antibiotics were added as follows: ampicillin (sodium salt, 100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (30 μg/ml), and tetracycline (hydrochloride, 10 μg/ml). Plasmids are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Relevant phenotype | Selective marker(s)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pBR329 | Cloning vector; PtaclacIq | Ap, Cm, Tc | 9 | |

| pDB127 | pDB126Δ[RP4 SfiI-SspI 48374-46670]b | (TrbB-TrbM)+ (TraF-TraM)+ TraG− | Cm | 2 |

| pFS241M | pMS470Δ8Δ[NdeI-HindIII]Ω[his6 RP4 48495-46588 (T47936G)]c | His6-TraGK187T+ | Ap | This work |

| pGS002 | pMS470Δ8Δ[NdeI-HindIII]Ω[his6 linker] | Ap | This work | |

| pGS003Δ1 | pMS470Δ8Δ[EcoRI-SmaI; NdeI-HindIII]Ω[NdeI/NsiI/BclI/HindIII/ SacI linker] | Ap | This work | |

| pGS006Δ1 | pGS002Δ[NdeI-HindIII]Ω[RP4 48387-46588] | His6-TraGΔ1+ | Ap | This work |

| pGS006Δ2 | pGS002Δ[NdeI-HindIII]Ω[RP4 48201-46588] | His6-TraGΔ2+ | Ap | This work |

| pGS007 | pGS003Δ1Ω[NsiI-NsiI R388 16-1638]d | TrwB+ | Ap | This work |

| pGS011 | pGS006Δ2Δ[SfiI-SfiI]Ω[pFS241M SfiI-SfiI 1467-bp fragment] | His6-TraGΔ2K187T+ | Ap | This work |

| pGS012Δ1 | pGS002Δ[NdeI-HindIII]Ω[R388 229-1638] | His6-TrwBΔ1+ | Ap | This work |

| pJF143 | pBR329Ω[BamHI, BamHI-XmaIII linker, RP4 XmaIII-AccI 50995-51269, AccI-BamHI linker] | OriT+ | Ap, Cm | 11 |

| pMS119EH | Cloning vector; Ptac lacIq | Ap | 40 | |

| pMS470Δ8 | Cloning vector; phage T7 gene10 SD sequence; Ptac lacIq | Ap | 3 | |

| pSK470 | pMS470Δ8Δ[NdeI-HindIII]Ω[RP4 48,495-46.588 kb] | TraG+ | Ap | 38 |

Reagents.

The following reagents were obtained from the suppliers indicated: Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) Superflow (Qiagen), Superdex 200 columns and radioactive nucleotides (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), nucleotides (Roche Molecular Biochemicals or Sigma), 2′,3′-O-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)ATP, disodium salt (TNP-ATP) and TNP-ADP (Molecular Probes), adenosine-5′-(γ-thio)-triphosphate, sodium salt (ATPγS) and adenosine-5-[(β,γ)-imido]triphosphate, triethylammonium salt (AppNp) (Jena Bioscience), enzymes (New England Biolabs), and Brij 58 and Triton X-100 (Sigma).

Buffers.

The following buffers were used: buffer A (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 40 mM NaCl, 8% [wt/vol] sucrose, 0.4 mg of lysozyme/ml, 0.15% Brij 58), buffer B (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 100 mM NaCl, 0.25% Brij 58), buffer C (50 mM KH2PO4-K2HPO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), buffer D (50 mM Tris-H3PO4 [pH 7.0], 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT), buffer E (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA), buffer F (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% [wt/vol] glycerol, 0.01% Brij 58), buffer G (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% Brij 58, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin [BSA]/ml), and buffer H (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.7]-20 mM NaCl).

DNA techniques.

Standard molecular cloning techniques were performed as described previously (36). pGS002, a vector for construction and overexpression of His6-tagged genes, was generated as follows. pMS470Δ8 was digested with NdeI, and the resulting 5′ overhangs were removed by using mung bean nuclease. The plasmid was then digested with HindIII and ligated with a His6 linker, which was prepared by annealing of oligonucleotides CATGCACCATCACCATCACCATATGGGCATGCA and AAGCTTGCATGCCCATATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGCATG. pGS003Δ1 was constructed by insertion of an NdeI/NsiI/BclI/HindIII/SacI linker (annealed oligonucleotides TATGCATCCGTCTGATCAAGCTTGTCCATGAGCTCATCACCATCACCATCACTGAT and AGCTATCAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGAGCTCATGGACAAGCTTGATCAGACGGATGCA) into pMS470Δ8 (NdeI/HindIII). This was followed by deletion of an 18-bp EcoRI-SmaI fragment by consecutive restriction, removal of 5′ overhangs (using mung bean nuclease), and religation. RP4 traG deletion derivatives his6-traGΔ1 and his6-traGΔ2 in pGS006Δ1 and pGS006Δ2 were generated by PCR using pSK470 as a template. Forward primers were CGTTCGAGCATATGACCGCGACGCAATATTTCGCCC and GCCGTCACGCATATGGTCAAGGC (nucleotides corresponding to the RP4 sequence are italicized, deviations from the original sequence are boldfaced, and the introduced NdeI site is underlined), and the reverse primer in both reactions was CTGTTTTATCAGACCGCTTCTGCG. pFS241M was generated by PCR with pBS140(K187T) (2) as the template and primers GCATTCCCATATGCACCATCACCATCACCATAAGAACCGAAACAACG and GCCTACGAAGCTTGGTGAGGCGCTGGAAGC. pGS007 was prepared by ligation of a 1,617-bp NsiI fragment of pSU4054 (4) into pGS003Δ1. The R388 trwB deletion derivative his6-trwBΔ1 in pGS012Δ1 was generated by PCR with pGS007 as the template, primer GTTGTTTGTCTGGCATATGAATAGCGTCG (nucleotides corresponding to the R388 sequence are italicized), and the same reverse primer as that used for pGS006Δ1. PCR fragments were generated with DeepVent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). Nucleotide sequences of PCR fragments were verified.

Conjugations.

Mating experiments to determine transfer frequencies of RP4-mediated conjugation were carried out on filters (2). HB101 cells carrying pDB127 (TraG−) plus pSK470 (TraG+), pGS006Δ1 (His6-TraGΔ1+), or pGS006Δ2 (his6-traGΔ2+) served as donors, and HB101 Nxr was used as a recipient.

Protein purification.

For overproduction, broth cultures of the indicated E. coli strains were grown at 30°C. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-mediated induction of expression and harvesting, resuspension, and freezing of cells were performed as described previously (19). Further steps were carried out at 4°C or on ice unless otherwise noted. RP4 His6-TraG and TraI were purified as described previously (30, 38). His6-TraGK187T was purified from SCS1(pFS241M) in analogy to His6-TraG. His6-TraGΔ2 was purified as follows. SCS1(pGS006Δ2) cells (19.7 g, resuspended in 100 ml of 200 mM Tris [pH 7.6]-20 mM spermidine-HCl-2 mM EDTA) were thawed, supplemented with 200 ml of buffer A, and stirred for 90 min at room temperature. After centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 45 min, the supernatant was kept and the pellet was resuspended in 100 ml of buffer B by using a Dounce homogenizer. The suspension was centrifuged as before, and the supernatants of the two centrifugation steps were combined. Proteins were precipitated by addition of 147 g of (NH4)2SO4 (60% saturation), collected by centrifugation at 25,000 × g for 30 min, and resuspended in 35 ml of buffer C (fraction I, 35 ml). Fraction I was dialyzed against buffer C and applied to a Ni-NTA column. The column was washed with buffer C alone and with buffer C containing 10% (vol/vol) glycerol and 20 mM imidazole (pH 7.6). Proteins were eluted with buffer C containing 250 mM imidazole (pH 7.6). Fractions containing His6-TraGΔ2 were pooled (fraction II, 97 ml), dialyzed against buffer D, and applied to a phosphocellulose P11 column. Adsorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient (40 to 600 mM NaCl) in buffer D. His6-TraGΔ2-containing fractions were pooled and concentrated by dialysis against buffer E containing 20% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 20000 (fraction III, 17.5 ml). His6-TraGΔ2K187T was purified from SCS1(pGS011) by following the protocol used for TraGΔ2, starting with 19.1 g of cells in 100 ml of buffer. Purification of His6-TrwBΔ1 from SCS1(pGS012Δ1) was done similarly with 16.4 g of cells in 80 ml of buffer, except that the NaCl concentration in buffer A and buffer B was 1 M. Protein purity and concentrations were determined by laser densitometric quantification of Coomassie blue (Serva)-stained gels with serial concentrations of BSA as a reference, by using the Personal Densitometer scanning device (Amersham Biosciences) and ImageQuant software (version 5.0). The identity of TraG derivatives was confirmed by Western blot analysis with a TraG-specific antiserum (46). Purified proteins were stored at −20°C in buffer E containing 50% (wt/vol) glycerol.

Gel filtration.

A Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column was calibrated with a gel filtration standard (Bio-Rad) consisting of four globular proteins of 670, 158, 44, and 17 kDa and vitamin B12 (1.4 kDa). The column was run with buffer F at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. Protein elution was monitored at a λ of 280 nm. TraG, TraGΔ2, and TrwBΔ1 were subjected to gel filtration under the same conditions. A trend line correlating the elution volumes of the gel filtration standards to the corresponding Mrs was used to obtain estimates of the Mrs of TraG, TraGΔ2, and TrwBΔ1.

Fragment retardation assay.

A 773-bp AccI-AvaI DNA fragment of pBR329 (Table 1) was 5′ labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Thirty-six femtomoles of the labeled fragment was incubated for 30 min at 37°C with different amounts of TraGΔ2 (1 to 5 pmol) or TrwBΔ1 (0.5 to 3 pmol) in a total volume of 20 μl of buffer G. Samples were electrophoresed on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels as described previously (47). The 32P-labeled DNA was visualized by the storage phosphor technology and analyzed with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Complex formation between protein and DNA was determined by monitoring the decrease in the amount of free DNA. The amount of free DNA in each lane was quantified with reference to the amount of free DNA present in the absence of protein. Competition or inhibition of DNA binding by single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), Mg2+, ATP, or ADP was analyzed by quantifying the displacement of bound double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) fragments from dsDNA-protein complexes. Seventy-five femtomoles of 32P-labeled DNA fragments obtained by DraI/AccI restriction of pJF143 (Table 1) was incubated as before with 10 pmol of TraGΔ2 or 3 pmol of TrwBΔ1. After 10 min, MgCl2, ATP, ADP, or ssDNA was added as appropriate, and mixtures were incubated for another 20 min at 37°C and electrophoresed as before. The bound and free DNA fragments were visualized and quantified as before, and the fraction of free DNA versus total DNA was calculated to determine the percentage of complex resolution.

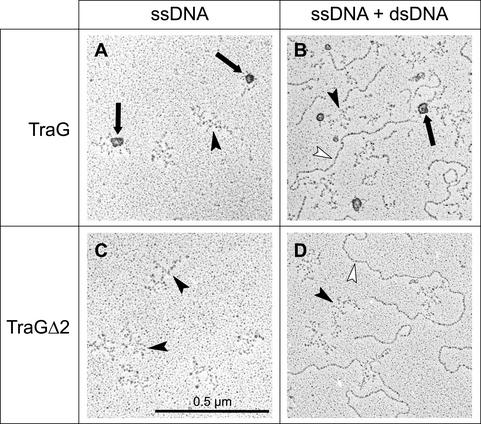

Transmission electron microscopy.

dsDNA (25 fmol of pJF143 digested with EcoRI and BamHI) and/or ssDNA (25 fmol of M13 mp18) was incubated for 10 min at room temperature with TraG or TraGΔ2 (0.48 pmol each). Following fixation with 0.2% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde for 10 min, the samples were prepared for electron microscopy (with a Philips EM400) by adsorption to mica as described previously (39).

Nucleotide binding.

The fluorescent nucleotide analogues TNP-ATP and TNP-ADP were used to study nucleotide-binding. Proteins and nucleotides were diluted in buffer H in a total volume of 400 μl. Final concentrations of NaCl were adjusted to 36 mM (for TraGΔ2 and TraGΔ2K187T) or 50 mM (for TrwBΔ1). Mixtures were incubated for 20 s before measurement. Fluorescence spectra were taken at room temperature by using a Shimadzu RF-5000 spectrofluorometer with excitation at 410 nm and emission scanning in the range of 470 to 620 nm. The fluorescence maxima were determined graphically. For determination of Kd, 7 μM protein solutions were titrated with TNP-ATP or TNP-ADP. The Kd values of unlabeled ATP and ADP, as well as the inhibition constant of Mg2+, were determined by displacement of protein-bound TNP-nucleotides. Seven-micromolar protein solutions were incubated for 20 s with 50 μM TNP-ATP or 70 μM TNP-ADP (50 μM TNP-ADP in the case of TrwBΔ1). ATP, ADP, or MgCl2 (from 0.5 or 0.1 M stock solutions in buffer H) was added, and fluorescence was measured after incubation for 20 s.

Enhanced fluorescence (ΔF) was calculated as the difference between total fluorescence (Ft) and the intrinsic fluorescence of TNP-nucleotides (TNP-N), buffer, and proteins:

|

(1) |

ΔF represents the amount of receptor-ligand complexes (RL) that are formed throughout the titration. ΔF reaches a maximum (ΔFmax) as the receptor becomes saturated, i.e., when RL equals the total receptor concentration (Rt):

|

(2) |

RL/Rt represents the fractional saturation of the receptor. Replacement of RL by an expression that relates RL, Rt, ligand (L), and Kd and takes ligand depletion into account (17) results in equation 3:

|

(3) |

Displacement of TNP-nucleotides by unlabeled nucleotides or by Mg2+ is described by equation 4:

|

(4) |

ΔFmax and ΔFmin are the fluorescences at the start and at the end of titration, respectively, and L is the concentration of the competitor (ATP, ADP, or Mg2+). IC50 represents the concentration of the competitor necessary to displace 50% of bound TNP-nucleotides. It is related to the inhibition constant (Ki) of the competitor (6) as follows:

|

(5) |

Lt is the total concentration of the TNP-nucleotide at the start of titration, and KdTNP-N is the dissociation constant of the respective TNP-nucleotide. In the case of displacement by ATP or ADP, Ki corresponds to KdATP or KdADP, respectively. The coefficients of independent values in equations 3 and 4 were fitted to the data by using Sigma Plot (version 2.0, copyright 1986 to 1994; Jandel Corp.).

Protein interaction analysis by surface plasmon resonance (SPR).

Interactions between TraI and either TraG, TraGK187T, or TraGΔ2 were studied by using the Biacore 2000 optical biosensor system (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) with a B1 pioneer sensor chip as described previously (38). The chip was loaded with 480 response units (RU) of BSA (FC2), 498 RU of TraI (FC3), and 460 RU of TraGΔ2 (FC4). Dilutions were made in HBS-EP buffer (Biacore AB). For real-time analysis of interaction with the immobilized proteins, 100 nM solutions of TraGK187T or TraGΔ2 were injected into the chip (FC1, -2, -3, and -4). Signals were corrected for nonspecific binding by subtracting curves for BSA interaction from each curve. Binding constants were determined with the BIAevaluation software (version 3.1, copyright 1994 to 1999, Biacore AB), by applying the Langmuir binding model for computational fitting.

RESULTS

The N-terminal membrane anchor of RP4 TraG is essential for conjugative transfer.

His-tagged (His6) deletion derivatives TraGΔ1 and TraGΔ2, lacking the first 36 or the first 102 residues of TraG, respectively, were constructed (Fig. 1). TraGΔ1 lacks the short cytoplasmic N terminus and the first of two transmembrane domains of TraG. In TraGΔ2, the periplasmic domain and the second transmembrane domain are additionally removed. The corresponding plasmids encoding TraGΔ1 and TraGΔ2 (Table 1) were unable to restore the transfer activity in complementation experiments with pDB127 (ΔtraG). In contrast, both full-length TraG and His6-TraG were effective in complementing pDB127 (38). We conclude that membrane anchorage of TraG is required for transfer activity.

FIG. 1.

Properties of deletion derivatives of RP4 TraG lacking transmembrane segments. A hydophobicity profile (21) of TraG depicts the hydrophobic regions of the protein. The domain structures of TraG and derivatives TraGΔ1 and TraGΔ2 are schematically represented. The transfer activity of each protein is indicated as positive (+) or negative (−). Cytoplasmic domains (open boxes), transmembrane segments (TM1 and TM2) (solid boxes), a periplasmic domain (hatched box), and two nucleotide-binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) (shaded boxes) are indicated. The sequence of the conserved Walker motif A in NBD1 is given below the diagram, with residue K187 boldfaced. The numbers indicating amino acid (AA) positions at the start of the proteins are the positions relative to the full-length protein.

Truncated derivatives of RP4 TraG and R388 TrwB with increased solubility were purified.

TraG derivatives TraGΔ1 and TraGΔ2 were overproduced and assayed for solubility. Under native conditions, by use of the mild nonionic detergent Brij 58 or Triton X-100, TraGΔ1 remained insoluble. In contrast, TraGΔ2 proved to be highly soluble and therefore was selected for purification. The crude extract, containing 42% TraGΔ2, was purified by successive Ni-NTA affinity and phosphocellulose P11 chromatography, yielding a TraGΔ2 preparation of 85% purity (Table 2). TraGΔ2K187T, containing a mutation in the putative nucleotide-binding domain 1 (NBD1) (Fig. 1), was purified similarly (Fig. 2). R388 TrwBΔ1 is identical to TrwBΔN70, whose purification has been described previously (27), except that TrwBΔ1 carries an N-terminal His6 tag. TrwBΔ1 was also purified by consecutive Ni-NTA and phosphocellulose P11 chromatography, yielding a TrwBΔ1 preparation of 97% purity (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Purification of TraGΔ2, TraGΔ2K187T, and TrwBΔ1

| Protein | Fraction | Purification step | Total protein (mg) | Yield (%)a | Purity (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TraGΔ2 | I | Crude extract | 645 | 100 | 42 |

| II | Ni-NTA | 315 | 80 | 69 | |

| III | Phosphocellulose P11 | 98 | 31 | 85 | |

| TraGΔ2K187T | I | Crude extract | 753 | 100 | 30 |

| II | Ni-NTA | 344 | 94 | 62 | |

| III | Phosphocellulose P11 | 107 | 38 | 80 | |

| TrwBΔ1 | I | Crude extract | 715 | 100 | 44 |

| II | Ni-NTA | 264 | 81 | 97 | |

| III | Phosphocellulose P11 | 261 | 80 | 97 |

Based on yield of first fraction of TraGΔ2, TraGΔ2K187T, or TrwBΔ1.

Laser densitometric evaluation of Coomassie blue-stained gels.

FIG. 2.

Truncated derivatives of RP4 TraG and R388 TrwB were purified in two steps. Shown are Coomassie blue-stained gels of samples collected during the purification of TraGΔ2K187T (A) and TrwBΔ1 (B), resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lanes 1, marker proteins (sizes in kilodaltons are indicated). Lanes 2, sodium dodecyl sulfate whole-cell extracts (20 μg). Lanes 3 to 5, samples of native protein extracts. Lanes 3, fraction I (17 μg); lanes 4, fraction II (9 μg in panel A and 7 μg in panel B); lanes 5, fraction III (7 μg).

Removal of the membrane anchor of TraG suppresses aggregation and results in loss of relaxase-binding ability.

Upon gel filtration, TraG behaves as a large oligomer or aggregate and solubilized TrwB forms a mixture of monomers and hexamers (16, 38). In contrast, the truncated derivatives TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1, which were characterized in the present study, behaved strictly as monomers in solution (Table 3). Aggregates of full-length TraG were also visualized by electron microscopy of TraG-DNA complexes (Fig. 3). When TraGΔ2 was analyzed analogously, however, no aggregates were seen and the protein was altogether invisible. Probably a single monomer of TraGΔ2 was too small to be detected by electron microscopy. Our results indicate that the membrane anchors of TraG and TrwB contain a domain responsible for protein-protein interactions that lead to protein oligomerization or aggregation in vitro. Interactions of TraG derivatives with RP4 relaxase (TraI) were measured with the optical biosensor system Biacore 2000, which uses SPR technology. TraI, TraGΔ2, and BSA (used as a reference) were immobilized on sensor chip surfaces, and real-time interactions with TraG derivatives were monitored (Fig. 4). TraGK187T interacted with TraI to the same extent as had previously been observed for wild-type TraG (38). As before, association occurred rapidly (ka ≈ 105 M−1) and dissociation was slow (Kd ≈ 10−4 s−1). In contrast, derivatives TraGΔ2 and TraGΔ2K187T did not interact with TraI (shown for TraGΔ2 in Fig. 4B). Thus, relaxase binding of TraG occurred independently of the nucleotide-binding signature at residue K187 but did require the membrane anchor of TraG. Interaction of full-length TraG with TraGΔ2 was weak and barely detectable (shown for TraGK187T in Fig. 4A). Also, TraGΔ2 self-interactions were absent (Fig. 4B). These data are in line with the previous observation that, unlike full-length TraG, TraGΔ2 is a monomer in solution.

TABLE 3.

Oligomeric states of TraG, TraGΔ2, and TrwBΔ1

| Protein | Calculated Mr (103) of the monomera |

Mr (103) evaluated by:

|

Deduced oligomeric state | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGEb | Gel filtration | |||

| TraG | 70.8 | 71.2 | >1,300c | >18c |

| TraGΔ2 | 59.7 | 59.3 | 50-60 | 1 |

| TrwBΔ1 | 49.57 | 47.3 | 27-33 | 1 |

Calculated from the predicted amino acid sequence.

SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Equivalent to a higher-order oligomer or aggregate.

FIG. 3.

Removal of the membrane anchor of TraG suppresses its oligomerization. Shown are electron microscopic images of full-length TraG (A and B) or TraGΔ2 (C and D) preparations. The proteins were incubated either with ssDNA alone (A and C) or with a 1:1 mixture of ssDNA and dsDNA (B and D) prior to fixation and adsorption to mica. Solid arrowheads, ssDNA molecules; open arrowheads, dsDNA molecules. Large protein oligomers bound to ssDNA were present in TraG preparations (indicated by solid arrows) but absent in TraGΔ2 preparations.

FIG. 4.

Interactions of TraG derivatives with RP4 relaxase (TraI). Complex formation between TraGK187T, TraGΔ2, and TraI was measured by SPR analysis on sensor chip surfaces. The sensor chip consisted of flow cells containing immobilized TraI (TraI∗) or immobilized TraGΔ2 (TraGΔ2∗). A reference cell with immobilized BSA served as a negative control. Real-time interactions with the immobilized proteins were monitored by injecting 100 nM solutions of TraGK187T (A) or TraGΔ2 (B) through the flow cells for 4 min. The signals (in response units) were corrected by subtracting the signal obtained from interaction with BSA. The start (0 min) and end (4 min) of injections are indicated by dashed lines delimiting association time (from 0 to 4 min) and dissociation time (from 4 min to infinity).

TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 bind ATP and ADP.

TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 were assayed for nucleotide binding by studying the binding of the fluorescent ATP and ADP derivatives TNP-ATP and TNP-ADP. Binding of TNP-nucleotides causes an increase in fluorescence (enhanced fluorescence), a phenomenon that has been widely used to characterize the nucleotide-binding abilities of proteins (20). Fluorescence enhancement emerges from the changes in polarity in the near environment of the TNP moiety upon binding (14, 26). TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 produced significant fluorescence enhancement of TNP-ATP and TNP-ADP (Fig. 5). The fluorescence increase was coupled with a blue shift of the fluorescence maximum from 542 to 528 nm, suggesting that the TNP-nucleotides bind to a hydrophobic region of the protein (15). Competition experiments confirmed that nucleotide binding was specific, since addition of an unlabeled nucleotide to TNP-nucleotide-protein complexes considerably reduced the fluorescence (Fig. 5; compare curves 3 with curves 4). In control experiments without protein, TNP-nucleotide fluorescence remained unchanged when either the buffer contained in the used protein solutions or unlabeled nucleotides were added (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 bind TNP-ATP. The fluorescent ATP analogue TNP-ATP displayed enhanced fluorescence upon binding by TraGΔ2 (A) and TrwBΔ1 (B). Fluorescence spectra 1 to 4 were taken from the following samples: spectrum 1, protein (7 μM); spectrum 2, TNP-ATP (50 μM); spectrum 3, protein (7 μM) plus TNP-ATP (50 μM); spectrum 4, protein (7 μM) plus TNP-ATP (50 μM) in the presence of ATP (10 mM). Fluorescence intensities are expressed in arbitrary units (AU).

Kds for the binding of TNP-ATP and TNP-ADP were determined by titrating 7 μM solutions of TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 with TNP-nucleotides until saturation was observed (shown for TraGΔ2 in Fig. 6A and B). Saturation of the proteins by TNP-nucleotides is well described by a function that relates fluorescence enhancement (ΔF) with total TNP-nucleotide concentration, total protein concentration, Kd, and the maximum fluorescence enhancement (equation 3 in Materials and Methods). Computationally fitted Kds for TNP-ATP and TNP-ADP binding of TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 were in the 4 to 5 μM range (Table 4).

FIG. 6.

Determination of the Kds for ATP and ADP binding of TraGΔ2. (A and B) Saturation curves obtained by titration of TraGΔ2 (7 μM) with TNP-ATP and TNP-ADP, respectively. Binding of TNP-nucleotides was monitored by measuring the fluorescence enhancement, i.e., the difference between the intrinsic TNP-nucleotide fluorescence and the fluorescence of bound TNP-nucleotides. The curves represent the best fit obtained with equation 3 (Materials and Methods), which determined the Kds for TNP-nucleotide binding. (C and D) Displacement of bound TNP-nucleotides by unlabeled nucleotides, causing a decrease in fluorescence. (C) ATP was added to a mixture of TraGΔ2 (7 μM) and TNP-ATP (50 μM). (D) ADP was added to a mixture of TraGΔ2 (7 μM) and TNP-ADP (70 μM). The curves were calculated by using equation 4, which contains constants for minimal and maximal fluorescence (Fmin and Fmax). The calculated Kds are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Kd for binding of ATP, ADP, and fluorescent TNP-nucleotides

| Protein | KdTNP-ATP (μM) | KdTNP-ADP (μM) | KdATP (mM) | KdADP (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TraGΔ2 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 0.34 | 0.37 |

| TrwBΔ1 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| TraGΔ2K187T | 6.0 | 7.2 | 0.81 | 1.64 |

Binding of TNP-nucleotides has often been observed to be stronger than binding of unlabeled nucleotides. This can be attributed to hydrophobic interactions between the TNP moiety and the protein that should further stabilize complexes, provided that nucleotide binding itself is not disturbed. In order to determine the true Kds of ATP and ADP, the displacement of bound TNP-nucleotides by unlabeled nucleotides was quantified. Titration of TNP-nucleotide-saturated TraGΔ2 or TrwBΔ1 with an excess of the respective nucleotide caused a progressive decrease in fluorescence (shown for TraGΔ2 in Fig. 6C and D). Computational fitting determined the concentration of ATP or ADP that caused 50% dissociation of the TNP-nucleotide-protein complex (IC50), which, in combination with the Kd of TNP-nucleotide binding, provided the Kd for ATP or ADP binding (Table 4). The Kd of nucleotide binding was hereby determined to be in the range of 0.3 to 0.4 mM for TraGΔ2; nucleotide binding was somewhat stronger for TrwBΔ1 (Kd, 0.1 to 0.2 mM). Thus, binding of unlabeled nucleotides was significantly lower than binding of fluorescent TNP derivatives (30- to 40-fold lower for TrwBΔ1 and up to 80-fold lower for TraGΔ2).

Mutation in the putative nucleotide-binding site of TraG (TraGΔ2K187T) causes reductions in its ATP- and ADP-binding abilities.

Nucleotide binding of the derivative TraGΔ2K187T was determined as before, by monitoring the fluorescence enhancement of TNP-ATP and TNP-ADP. The binding of TNP-nucleotides was only slightly weaker than that seen with TraGΔ2. The Kds were determined to be 6.0 μM for TNP-ATP and 7.2 μM for TNP-ADP. However, displacement of TNP-nucleotides by unlabeled nucleotides revealed that the nucleotide-binding ability of the TraGΔ2K187T mutant was reduced (Fig. 7). The KdATP (0.81 mM) and KdADP (1.64 mM) indicated 2.4- and 4.5-fold decreases in binding affinity for ATP and ADP, respectively.

FIG. 7.

The TraGΔ2K187T point mutation derivative has a decreased nucleotide-binding ability. The Kds for ATP and ADP binding of TraGΔ2K187T were determined by monitoring the displacement of protein-bound TNP-nucleotides by unlabeled nucleotides. Displacement manifested itself as a decrease in fluorescence. (A) ATP was added to a mixture of TraGΔ2K187T (7 μM) and TNP-ATP (50 μM). (B) ADP was added to a mixture of TraGΔ2K187T (7 μM) and TNP-ADP (70 μM). The curves were calculated by using the best fit to equation 4 (Materials and Methods), yielding Kds for ATP and ADP binding (Table 4).

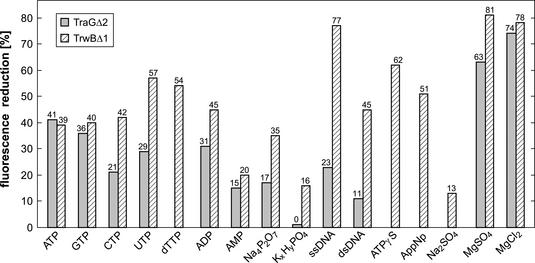

ATP binding is inhibited in the presence of Mg2+ and DNA and is competed for by other nucleotides.

In analogy to the competition experiments performed with excess ATP (see above), other nucleotides and nucleotide derivatives were assayed for their abilities to displace TNP-ATP. Additionally, the effects of inorganic salts and DNA were tested (Fig. 8). For both TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1, Mg2+ had the largest effect (80% reduction in ΔF). This was also the case for displacement of protein-bound TNP-ADP (data not shown). The Ki for Mg2+ inhibition of TraGΔ2-TNP-ATP binding was determined to be 82 μM. DNA, especially ssDNA, was also a strong inhibitor for TNP-ATP binding of TrwBΔ1 but was a much weaker inhibitor for that of TraGΔ2. All nucleotides and nucleotide derivatives tested were able to compete with TNP-ATP to a certain extent. In the case of TraGΔ2 binding, ATP itself was the best natural competitor of TNP-ATP, whereas UTP and dTTP were the most effective competitors for TrwBΔ1 binding. These observations indicated that purine or pyrimidine moieties of nucleotides did not particularly add to the specificity of nucleotide binding of TraGΔ2 or TrwBΔ1. The synthetic ATP analogues ATPγS and AppNp were able to displace TNP-ATP to a higher extent than ATP. ADP was a good competitor for both proteins, whereas competition by AMP was poor. Similarly, pyrophosphate (PPi) was a much better competitor than phosphate, although at a lower rate overall than ADP. Thus, there seems to be binding specificity for at least the diphosphate moiety of NTPs or nucleoside diphosphates, whereas purine or pyrimidine moieties are more or less equally well bound and merely add to the strength of binding.

FIG. 8.

Displacement of bound TNP-ATP by other nucleotides, DNA, and inorganic salts. The fluorescence of TNP-ATP-protein mixtures was measured before and after addition of the indicated compounds. The percent fluorescence reduction was set as a measure of the displacement of bound TNP-ATP, i.e., as a measure of competition for the binding site or inhibition of nucleotide binding. Concentrations were as follows: TraGΔ2 or TrwBΔ1, 10 μM; TNP-ATP, 50 μM; nucleotides, KxHyPO4, AppNp, Na2SO4, MgSO4, and MgCl2, 5 mM; Na4P2O7 and ATPγS, 2.5 mM; ssDNA, 18 nM; dsDNA, 15 nM.

TraG and TrwB derivatives bind dsDNA.

The DNA-binding ability of TraG was unaffected by the removal of the membrane anchor, as was seen in fragment shift experiments with TraGΔ2 (Fig. 9). Here, addition of protein to a 0.8-kbp DNA fragment caused a mobility shift of the fragment. Protein-dsDNA complexes did not produce a discrete band but accumulated in the wells of the gel. The apparent Kds (Kdapp) of TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 for binding of the 0.8-kb fragment were determined as 75 and 24 nM, respectively. Comparable dsDNA binding affinities were also found for TraG and TraGK187T (data not shown). We conclude that dsDNA binding requires neither the N-terminal membrane anchor nor the conserved residue K187 of the putative nucleotide-binding site.

FIG. 9.

TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 bind dsDNA. (A) Fragment shift experiment of TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 incubated with a 32P-labeled dsDNA fragment and electrophoresed on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. Addition of increasing amounts of protein (in picomoles) to the 0.8-kb dsDNA fragment (36 fmol) led to accumulation of protein-DNA complexes in the wells of the gel. (B) Bjerrum plot of free DNA as a function of protein concentration. Complex formation with TraGΔ2 (filled circles) or with TrwBΔ1 (open circles) was determined by quantifying the fraction of free DNA. The amount of protein necessary to bind half of the DNA was calculated by using the Hill-type equation that describes a symmetrical hyperbola ([A] = 1.5 pmol of TraGΔ2; [B] = 0.47 pmol of TrwBΔ1).

dsDNA binding is competed for by ssDNA and is weakly inhibited by the presence of Mg2+ and nucleotides.

In fragment shift experiments, ssDNA was observed to displace bound dsDNA from dsDNA-protein complexes (Fig. 10). Submolar ratios of ssDNA were sufficient to chase 50% of bound dsDNA, indicating that ssDNA was preferentially bound. The molar ratios (expressed in bases) necessary for 50% displacement were determined to be 1:5.4 (for TraGΔ2) and 1:8.7 (for TrwBΔ1). Electron microscopy confirmed that ssDNA is the preferred substrate: when equal amounts of ssDNA and dsDNA were incubated with TraG, complexes were formed exclusively with ssDNA (Fig. 3). In contrast, dsDNA-TraG complexes were abundantly seen in the absence of ssDNA (data not shown). Since nucleotide binding of TraG and TrwB was observed to be inhibited by the presence of DNA (see above), we tested whether nucleotides could reversibly inhibit DNA binding. DNA fragment shifts were thus performed in the presence or absence of ATP and ADP. Additionally, the effect of Mg2+ was tested (Fig. 10, lanes 6 to 8 and 14 to 16). With TraGΔ2, inhibition by Mg2+ was significant (24% complex resolution) but inhibition by ATP and ADP was very low. With TrwBΔ1, ATP was the strongest inhibitor (37% complex resolution), followed by ADP and Mg2+ (13 and 16% complex resolution, respectively). Thus, inhibition by nucleotides was observed only for TrwBΔ1, whereas inhibition by Mg2+ applied to both proteins, although at a much lower degree than had been observed in the case of nucleotide binding.

FIG. 10.

Displacement of protein-bound dsDNA by ssDNA, Mg2+, or nucleotides. 32P-labeled dsDNA fragments (75 fmol each) were incubated with TraGΔ2 (10 pmol) (lanes 1 to 8) or TrwBΔ1 (3 pmol) (lanes 9 to 16) and then supplemented with a competitor or inhibitor. Complexes were separated from free DNA by electrophoresis on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. DNA fragments (sizes indicated in kilobase pairs) and complexes were visualized by autoradiography. Lanes 1 and 9, protein plus dsDNA; lanes 2 to 5, ssDNA added at 6, 9, 12, and 18 fmol, respectively; lanes 10 to 13, ssDNA added at 3, 6, 9, and 18 fmol, respectively; lanes 6 and 14, MgCl2 (10 mM) added; lanes 7 and 15, ATP (10 mM) added; lanes 8 and 16, ADP (10 mM) added.

DISCUSSION

Type IV secretion is a common secretory pathway which has become increasingly important since the discovery of its involvement in the pathogenicity of a growing number of bacterial species. The detailed mechanisms of type IV secretion machineries remain unclear despite extensive investigation by many research groups (reviewed in reference 8). A set of proteins that participate in the formation of a membrane-spanning complex and in pilus synthesis is conserved in these secretion systems (7, 35, 43). Additionally, a membrane protein that does not directly join in the latter functions is required: the TraG-like protein (coupling protein). This protein seems to function in actively transporting the substrate to be secreted through the inner membrane. Several observations have led to this model, which was originally proposed by Willetts and Wilkins (42). TraG-like proteins were seen to bind DNA (27, 29, 38) and to interact with protein components associated with DNA (10, 38). The crystal structure of a truncated TraG-like protein (TrwBΔN70) suggested that the cytoplasmic domain of TrwB forms a hexameric channel structure that probably protrudes through the inner membrane (13). The energy for the postulated DNA-protein transport mechanism might be provided by hydrolysis of nucleotides, since sequence analysis identified the family of TraG-like proteins as putative NTPases (23). Genetic experiments have confirmed this view. Amino acid substitutions in the conserved nucleotide-binding motifs, as in the TraG derivatives TraGK187T and TraGD449N, produced a transfer-defective phenotype (2). However, the model lacks definite proof. NTPase assays with four different purified TraG-like proteins failed to detect such an activity (27, 38). A specific conformation or an additional factor may be required for these proteins to induce NTPase activity. Nonetheless, TraG-like proteins were shown, if not to hydrolyze, at least to bind nucleotides (27; this work).

The present study focuses on the nucleotide-binding properties of two TraG-like proteins, TraG and TrwB, and attempts to dissect the multiple functions of TraG. Deletion derivatives lacking the membrane anchor (TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1) and point mutation derivatives with a mutation in the putative nucleotide-binding site (TraGK187T and TraGΔ2K187T) were constructed and purified (Fig. 1 and 2). Nucleotide binding was assayed by measuring the fluorescence increase in fluorescent nucleotide derivatives (TNP-nucleotides) upon binding. Apart from binding to ATP, TraGΔ2 and TrwBΔ1 were thereby shown to bind ADP (Fig. 5). Compared to TraGΔ2, mutant TraGΔ2K187T had a significantly reduced nucleotide-binding ability (Fig. 7), which may account for the transfer-defective phenotype of TraGK187T reported earlier (2). Competition experiments revealed that other NTPs were able to displace protein-bound ATP and that the diphosphate moiety of nucleotides was the core structure required for binding (Fig. 8). The presence of DNA markedly reduced the ATP binding of TrwBΔ1, and conversely, DNA binding was inhibited by the presence of ATP. This effect was less pronounced with TraGΔ2, whose DNA-binding capacity was merely lowered by the presence of nucleotides. Both proteins, however, responded strongly to the presence of Mg2+, which significantly inhibited ATP and ADP binding as well as DNA binding (Fig. 8 and 10). Inhibition of ATP binding by Mg2+ (more specifically, inhibition of TNP-ATP binding) has been reported previously for cation pumps KATP (41) and Ca2+-ATPase (28).

Full-length TraG was recently reported to form large oligomers that interact with relaxase, which is an RP4-encoded protein that covalently associates with the nic site of the origin of transfer (32, 38). Analysis of the truncated derivative TraGΔ2 revealed that removal of its membrane anchor prevented the interaction with relaxase. Gel filtration, electron microscopy, and protein interaction analysis also showed that, unlike TraG, TraGΔ2 is a monomer in solution (Table 3; Fig. 3 and 4). We conclude that the N-terminal membrane anchor of TraG (residues 1 to 102) is essential for TraG-TraG and TraG-relaxase interactions. Whereas TraG-TraG interactions lead to aggregation in vitro, they are probably important for the self-assembly of TraG in the cell membrane in vivo. Similar conclusions can be drawn from the observations with TrwB. While full-length TrwB forms hexamers, at least partially (16), the truncated derivatives TrwBΔN70 and TrwBΔ1 are strictly monomeric (27) (Table 3). The hexameric nature of TrwBΔN70 in its crystal structure, however, indicates that the truncated protein may still form multimers under the restrictive conditions imposed by crystal growth (i.e., high concentration and dehydration).

The failure of TraGΔ2 to oligomerize may be related to its failure to interact with relaxase. It is indeed conceivable that TraG assembly should occur prior to relaxase binding, since the protein needs first to be properly inserted into the membrane and to build its final putative pore-like architecture before binding to another bulky protein such as relaxase. Another possible explanation for the defect in the relaxase binding of TraGΔ2 is the assumption that the relaxase-interacting domain is situated in the deleted N terminus. This N terminus consists of a short cytoplasmic tail (residues 1 to 23) followed by a transmembrane segment, a periplasmic domain (residues 44 to 82), and a second transmembrane segment. After exclusion of the transmembrane segments, the periplasmic and cytoplasmic regions of the membrane anchor remain as possible domains for relaxase interaction. Since relaxase is a cytoplasmic protein, the periplasmic domain of TraG is unlikely to play a role in relaxase-interaction. Thus, apart from the possibility that oligomerization of the protein per se is a requirement for relaxase interaction, the short cytoplasmic domain preceding the first membrane segment may be required for this interaction, although it is probably too short to be a domain of its own.

T4SS function as active transporters for delivery of substrates destined for secretion. A question of central interest is how the energy for this transport is provided. Sequence analysis of T4SS-encoded proteins indicated that NTP hydrolysis may be the motor for type IV secretion, since three proteins with putative NTPase activity were identified. Apart from the TraG-like proteins, these include the VirB4-like and the VirB11-like proteins. Each of these proteins is an essential component of the T4SS studied. The proposed NTPase activity was confirmed in vitro for three proteins of the VirB11 family that were also seen to form hexamers (18, 19, 34). Furthermore, the crystal structures of HP0525 (H. pylori) and its nucleotide-bound form suggested a role in the export of substrates and/or in the assembly of the type IV secretion apparatus itself (37, 44). In contrast, purified forms of the VirB4-like proteins TrbE (RP4) and TrwK (R388) were found to lack NTPase activity. However, a mutation in the putative nucleotide-binding site produced a transfer-deficient phenotype (33). The same effect was observed for TraG-like proteins, which equally lack NTPase activity in vitro. Two TraG-like proteins, TraG and TrwB, were now shown to bind ATP as well as ADP, supporting the view that these proteins are somehow involved in an energy-driven transport process fueled by hydrolysis of nucleotides. Comparison of the crystal structures of TrwBΔN70 and the protein bound to the ATP analogue AppNp or GppNp has indicated that TrwB undergoes conformational changes upon NTP binding (12). Our results indicate that nucleotide binding of TraG and TrwB is inhibited by Mg2+. In this context, it is worth noting that no Mg2+ ion could be assigned in the structures of AppNp- or GppNp-bound TrwBΔN70, although the crystals were purposely grown in the presence of Mg2+. Thus, in agreement with our finding, Mg2+ did not contribute to nucleotide binding in these complexes; rather, the contrary should probably apply. In conclusion, we propose that TraG-like proteins either hydrolyze nucleotides themselves under inducing in vivo conditions that are not fulfilled in vitro or regulate the activity of a different NTPase (such as VirB11) by feeding it with nucleotides and/or discharging the products of hydrolysis. The fact that purified TraG proteins do not hydrolyze nucleoside triphosphates but do bind ATP as well as the product of its hydrolysis, ADP, supports the latter hypothesis. In this mechanism, release and binding of nucleotides could be triggered by Mg2+. Thus, TraG-like proteins, which are known to bind to substrates of type IV secretion, are likely also to be involved in their active export.

In the present work, it was shown that the TraG-like proteins TraG and TrwB bind ATP as well as ADP in the 10−1 mM range and that this binding activity is strongly reduced by Mg2+. Apart from characterizing the nucleotide-binding properties of TraG and TrwB in detail, we have functionally and structurally dissected several of their functions. Removal of the membrane anchor destroyed transfer activity. This was attributed to a defect in protein multimerization and in protein-relaxase interaction. In contrast, the DNA- and nucleotide binding activities of TraG and TrwB were functionally independent of oligomerization or relaxase binding and could be structurally localized to the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gerhild Lüder and Rudi Lurz for carrying out electron microscopic experiments. We extend thanks to Nicole Lorenz for practical help and Franca Blaesing for critical reading of the manuscript.

We thank Hans Lehrach for generous support. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M., P. A. Manning, C. Edelbluth, and P. Herrlich. 1979. Export without proteolytic processing of inner and outer membrane proteins encoded by F sex factor tra cistrons in Escherichia coli minicells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4837-4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balzer, D., W. Pansegrau, and E. Lanka. 1994. Essential motifs of relaxase (TraI) and TraG proteins involved in conjugative transfer of plasmid RP4. J. Bacteriol. 176:4285-4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzer, D., G. Ziegelin, W. Pansegrau, V. Kruft, and E. Lanka. 1992. KorB protein of promiscuous plasmid RP4 recognizes inverted sequence repetitions in regions essential for conjugative plasmid transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1851-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolland, S., M. Llosa, P. Avila, and F. de la Cruz. 1990. General organization of the conjugal transfer genes of the IncW plasmid R388 and interactions between R388 and IncN and IncP plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 172:5795-5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng, Y., and W. H. Prusoff. 1973. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 22:3099-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christie, P. J. 1997. Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-complex transport apparatus: a paradigm for a new family of multifunctional transporters in eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 179:3085-3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christie, P. J. 2001. Type IV secretion: intercellular transfer of macromolecules by systems ancestrally related to conjugation machines. Mol. Microbiol. 40:294-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covarrubias, L., and F. Bolivar. 1982. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. VI. Plasmid pBR329, a new derivative of pBR328 lacking the 482-base-pair inverted duplication. Gene 17:79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disqué-Kochem, C., and B. Dreiseikelmann. 1997. The cytoplasmic DNA-binding protein TraM binds to the inner membrane protein TraD in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 179:6133-6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fürste, J. P., W. Pansegrau, G. Ziegelin, M. Kröger, and E. Lanka. 1989. Conjugative transfer of promiscuous IncP plasmids: interaction of plasmid-encoded products with the transfer origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1771-1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomis-Rüth, F. X., G. Moncalián, F. de la Cruz, and M. Coll. 2002. Conjugative plasmid protein TrwB, an integral membrane type IV secretion system coupling protein. Detailed structural features and mapping of the active site cleft. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7556-7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomis-Rüth, F. X., G. Moncalián, R. Perez-Luque, A. Gonzalez, E. Cabezón, F. de la Cruz, and M. Coll. 2001. The bacterial conjugation protein TrwB resembles ring helicases and F1-ATPase. Nature 409:637-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiratsuka, T. 1976. Fluorescence properties of 2′ (or 3′)-O-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)adenosine 5′-triphosphate and its use in the study of binding to heavy meromyosin ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 453:293-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiratsuka, T. 1982. Biological activities and spectroscopic properties of chromophoric and fluorescent analogs of adenine nucleosides and nucleotides, 2′,3′-O-(2,4,6-trinitrocyclohexadienylidene)adenosine derivatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 719:509-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hormaeche, I., I. Alkorta, F. Moro, J. M. Valpuesta, F. M. Goñi, and F. de la Cruz. 2002. Purification and properties of TrwB, a hexameric, ATP-binding integral membrane protein essential for R388 plasmid conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:46456-46462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulme, E. C., and N. J. M. Birdsall. 1992. Strategy and tactics in receptor-binding studies, p. 63-174. In E. C. Hulme (ed.), Receptor-ligand interactions, a practical approach. Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 18.Krause, S., M. Bárcena, W. Pansegrau, R. Lurz, J. M. Carazo, and E. Lanka. 2000. Sequence-related protein export NTPases encoded by the conjugative transfer region of RP4 and by the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori share similar hexameric ring structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3067-3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause, S., W. Pansegrau, R. Lurz, F. de la Cruz, and E. Lanka. 2000. Enzymology of type IV macromolecule secretion systems: the conjugative transfer regions of plasmids RP4 and R388 and the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori encode structurally and functionally related nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases. J. Bacteriol. 182:2761-2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubala, M., K. Hofbauerova, R. Ettrich, V. Kopecky, R. Krumscheid, J. Plasek, J. Teisinger, W. Schoner, and E. Amler. 2002. Phe(475) and Glu(446) but not Ser(445) participate in ATP-binding to the alpha-subunit of Na+/K+-ATPase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297:154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157:105-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, M. H., N. Kosuk, J. Bailey, B. Traxler, and C. Manoil. 1999. Analysis of F factor TraD membrane topology by use of gene fusions and trypsin-sensitive insertions. J. Bacteriol. 181:6108-6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lessl, M., W. Pansegrau, and E. Lanka. 1992. Relationship of DNA-transfer-systems: essential transfer factors of plasmids RP4, Ti and F share common sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:6099-6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llosa, M., S. Bolland, and F. de la Cruz. 1994. Genetic organization of the conjugal DNA processing region of the IncW plasmid R388. J. Mol. Biol. 235:448-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 431-433. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Moczydlowski, E. G., and P. A. Fortes. 1981. Characterization of 2′,3′-O-(2,4,6-trinitrocyclohexadienylidine)adenosine 5′-triphosphate as a fluorescent probe of the ATP site of sodium and potassium transport adenosine triphosphatase. Determination of nucleotide binding stoichiometry and ion-induced changes in affinity for ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 256:2346-2356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moncalián, G., E. Cabezón, I. Alkorta, M. Valle, F. Moro, J. M. Valpuesta, F. M. Goñi, and F. de la Cruz. 1999. Characterization of ATP and DNA binding activities of TrwB, the coupling protein essential in plasmid R388 conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36117-36124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moutin, M. J., M. Cuillel, C. Rapin, R. Miras, M. Anger, A. M. Lompre, and Y. Dupont. 1994. Measurements of ATP binding on the large cytoplasmic loop of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase overexpressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:11147-11154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panicker, M. M., and E. G. Minkley, Jr. 1992. Purification and properties of the F sex factor TraD protein, an inner membrane conjugal transfer protein. J. Biol. Chem. 267:12761-12766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pansegrau, W., D. Balzer, V. Kruft, R. Lurz, and E. Lanka. 1990. In vitro assembly of relaxosomes at the transfer origin of plasmid RP4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6555-6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pansegrau, W., E. Lanka, P. T. Barth, D. H. Figurski, D. G. Guiney, D. Haas, D. R. Helinski, H. Schwab, V. A. Stanisich, and C. M. Thomas. 1994. Complete nucleotide sequence of Birmingham IncP alpha plasmids. Compilation and comparative analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 239:623-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pansegrau, W., G. Ziegelin, and E. Lanka. 1990. Covalent association of the traI gene product of plasmid RP4 with the 5′-terminal nucleotide at the relaxation nick site. J. Biol. Chem. 265:10637-10644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabel, C., A. M. Grahn, R. Lurz, and E. Lanka. 2003. The VirB4 family of proposed traffic nucleoside triphosphatases: common motifs in plasmid RP4 TrbE are essential for conjugation and phage adsorption. J. Bacteriol. 185:1045-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivas, S., S. Bolland, E. Cabezón, F. M. Goñi, and F. de la Cruz. 1997. TrwD, a protein encoded by the IncW plasmid R388, displays an ATP hydrolase activity essential for bacterial conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25583-25590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salmond, G. P. C. 1994. Secretion of extracellular virulence factors by plant pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 32:181-200. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Savvides, S. N., H. J. Yeo, M. R. Beck, F. Blaesing, R. Lurz, E. Lanka, R. Buhrdorf, W. Fischer, R. Haas, and G. Waksman. 2003. VirB11 ATPases are dynamic hexameric assemblies: new insights into bacterial type IV secretion. EMBO J. 22:1969-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schröder, G., S. Krause, E. L. Zechner, B. Traxler, H. J. Yeo, R. Lurz, G. Waksman, and E. Lanka. 2002. TraG-like proteins of DNA transfer systems and of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system: inner membrane gate for exported substrates? J. Bacteriol. 184:2767-2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiess, E., and R. Lurz. 2001. Electron microscopic analysis of nucleic acids and nucleic acid-protein complexes. Methods Microbiol. 20:293-323. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strack, B., M. Lessl, R. Calendar, and E. Lanka. 1992. A common sequence motif, -E-G-Y-A-T-A-, identified within the primase domains of plasmid-encoded I- and P-type DNA primases and the α protein of the Escherichia coli satellite phage P4. J. Biol. Chem. 267:13062-13072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vanoye, C. G., G. G. MacGregor, K. Dong, L. Tang, A. S. Buschmann, A. E. Hall, M. Lu, G. Giebisch, and S. C. Hebert. 2002. The carboxyl termini of K(ATP) channels bind nucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 277:23260-23270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willetts, N., and B. M. Wilkins. 1984. Processing of plasmid DNA during bacterial conjugation. Microbiol. Rev. 48:24-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winans, S. C., D. L. Burns, and P. J. Christie. 1996. Adaptation of a conjugal transfer system for the export of pathogenic macromolecules. Trends Microbiol. 4:64-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeo, H. J., S. N. Savvides, A. B. Herr, E. Lanka, and G. Waksman. 2000. Crystal structure of the hexameric traffic ATPase of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system. Mol. Cell 6:1461-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zechner, E. L., F. de la Cruz, R. Eisenbrandt, A. M. Grahn, G. Koraimann, E. Lanka, G. Muth, W. Pansegrau, C. M. Thomas, B. M. Wilkins, and M. Zatyka. 2000. Conjugative DNA transfer processes, p. 87-173. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 46.Ziegelin, G., W. Pansegrau, B. Strack, D. Balzer, M. Kröger, V. Kruft, and E. Lanka. 1991. Nucleotide sequence and organization of genes flanking the transfer origin of promiscuous plasmid RP4. DNA Sequence 1:303-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziegelin, G., E. Scherzinger, R. Lurz, and E. Lanka. 1993. Phage P4 α protein is multifunctional with origin recognition, helicase and primase activities. EMBO J. 12:3703-3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]