Abstract

We have carried out a mutational scan of the upstream region of the bacteriophage P2 FETUD late operon promoter, PF, which spans an element of hyphenated dyad symmetry that is conserved among all six of the P2 and P4 late promoters. All mutants were assayed for activation by P4 Delta in vivo, by using a lacZ reporter plasmid, and a subset of mutants was assayed in vitro for Delta binding. The results confirm the critical role of the three complementary nucleotides in each half site of the upstream element for transcription factor binding and for activation of transcription. A trinucleotide DNA recognition site is consistent with a model in which these transcription factors bind via a zinc finger motif. The mutational scan also led to identification of the −35 region of the promoter. Introduction of a σ70 −35 consensus sequence resulted in increased constitutive expression, which could be further stimulated by Delta. These results indicate that activator binding to the upstream region of P2 late promoters compensates in part for poor σ70 contacts and helps to recruit RNA polymerase holoenzyme.

P2 belongs to a group of serologically related temperate phages that share the ability to support the lytic multiplication of satellite (helper-dependent) phages P4 and φR73. Lytic growth of both P2 and the P2-dependent satellite phages requires the P2 late genes, which encode the proteins involved in capsid and tail synthesis and cell lysis (reviewed in references 4 and 16). P2 late-gene transcription depends upon the P2 ogr gene product. The P4 and φR73 δ genes encode transcription factors related to P2 Ogr that can directly activate transcription from the P2 late promoters when utilizing P2 as a helper for lytic growth. These activator proteins belong to a family of small zinc binding transcription factors that coordinate one atom of zinc with 4 Cys residues arranged in a conserved CX2CX22CX4C motif (11, 15, 19). Transcription from two late promoters on the P4 genome, Psid and PLL, is also activated by Ogr or Delta (5, 6).

The four P2 late promoters (2, 3) and the two P4 late promoters (5, 6) share features typical of positively regulated bacterial promoters recognized by RNA polymerase carrying the σ70 subunit. These promoters lack good homology to the −35 consensus sequence. Partial homology with the −10 consensus sequence in the different promoters exists to various extents, with the two most highly conserved nucleotides being retained in all cases. The most striking feature of these six late promoters, as well as other promoters positively regulated by members of this family of transcription factors (7, 23, 25), is a conserved upstream element of hyphenated dyad symmetry, with the consensus sequence TGT-N12-ACA, centered at about position −55 (Fig. 1). Previous deletion analysis of the P2 FETUD operon promoter PF (8) and a more detailed mutational analysis of the P4 Psid promoter (21) implicated this upstream region in promoter function. DNase I protection studies confirmed that this region is bound by P4 Delta, as well as the related activator proteins encoded by phages φR73 and PSP3 (9, 10) and a cryptic prophage in Serratia marcescens (17). In order to more fully elucidate the mechanism of activation of transcription from P2 late promoters, we have extended our analysis of PF by performing a detailed mutational analysis of the upstream region to determine the specific base pairs required for activation.

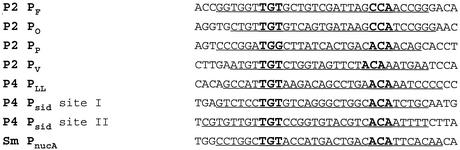

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the upstream sequences of promoters positively regulated by members of the P2 Ogr family of transcription factors. Included in this comparison are those promoters that have been shown in vitro to bind P4 Delta protein. Sequences are aligned at the upstream half of the inverted repeat; nucleotides corresponding to the conserved element of dyad symmetry are indicated in bold. Underlined bases designate the region of each promoter protected by Delta from DNase I digestion (9, 23). The binding sites are all centered at a position about 55 bp upstream of the transcription start sites, with the exception of Psid site II, which is centered at −18 (9), and PnucA, which is centered at −66 but also activates when positioned at −55 (23).

Design of the two-plasmid assay system.

Plasmid pUCF118 is a derivative of pUC118 (22) carrying a synthetic P2 PF promoter fragment from positions −69 to +39 (P2 nucleotides 17558 to 17665; GenBank accession no. AF063097) with a SmaI site at the 5′ end and a BamHI site at the 3′ end. This promoter fragment was ligated with pUC118 that was cleaved with SmaI and BamHI. Site-directed mutagenesis of pUCF118 was performed to create mutant derivatives of PF by using single-stranded DNA templates and the method described by Kunkel (13) or by incorporation of a phosphorylated mutant oligonucleotide during PCR amplification (18). All mutant constructs and cloned fragments generated by PCR amplification were verified by sequencing. For lacZ expression, the wild-type or mutant promoter fragments were excised from pUCF118 with EcoRI and BamHI and ligated with pMC1403 (1) that had been cleaved with the same two enzymes. This created a translational fusion between the 5′ end of the P2 F gene and lacZ. The nomenclature for the resulting plasmids corresponds to the changes introduced upstream of the transcription start site, e.g., pFWT (17) carries the wild-type promoter, pFCR6664 contains a replacement with three complementary nucleotides at positions −66 to −64, pF51A contains an adenine substitution at −51, etc.

A compatible plasmid was constructed to provide P4 Delta from an IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible promoter. Plasmid pDEB50 carries the δ gene under regulation of a variant T7A1 promoter with two LacI binding sites (PA1/04/03) (14) and was constructed in several steps. A 1.5-kb NsiI fragment from P4 (P4 nucleotides 10022 to 11504; accession no. X51522) was ligated with pUHE21-2 (gift of Herman Bujard) which had been cleaved with PstI, to yield pBJ12. The 5′ end of the psu gene (P4 nucleotides 10835 to 11179) was then removed by digestion with EagI and religation, to yield pBJ14. A 1.3-kb XhoI-NheI fragment was then excised from pBJ14, filled with Klenow fragment, and ligated with the Kanr lacIq-expressing plasmid pRG1 (R. Garcea, unpublished data) that had been cleaved and filled at the BamHI site. Plasmid pRTA1, which was used as a control to measure activator-independent background activity from the PF-lacZ fusions, was constructed in a similar fashion. A 220-bp XhoI-NheI fragment carrying the modified T7A1 promoter from pUHE24-2 (gift of Herman Bujard) was filled and ligated with pRG1 that had been cleaved and filled at the BamHI site.

Comparison of mutant promoter activities in vivo.

The relative activation of each mutant late promoter by Delta is shown in Fig. 2. PF-lacZ fusion plasmids were assayed in the Lac− strain C-2420 (9) carrying pDEB50 or pRTA1. Cells were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) plus appropriate antibiotics. Overnight cultures were diluted 250-fold into 0.5 ml of LB supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, 60 μg of kanamycin/ml, and 300 mM IPTG and grown for 5 h at 37°C with vigorous shaking. The cultures were then placed in an ice bath, and the cells were collected by brief centrifugation, washed with 1 volume of cold 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.8), centrifuged again, and resuspended in 1 ml of 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.8). The optical densities of the resuspended cultures were measured at 600 nm. Lysates were prepared by adding 1 volume of a solution containing 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.8), 2% Triton X-100, 5 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 5 mg of lysozyme/ml, and 2 mM dithiothreitol to 1 volume of resuspended culture and incubating the mixture for 20 min at room temperature. All lysates were stored at −80°C before assay. β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) expression was measured by using Galacton Plus substrate in the chemiluminescent β-Gal reporter gene assay (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Luminescence was measured with a VICTOR2 1420 multilabel counter (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass.) with a 5-s integration time. Three independent cultures for each sample were grown, and lysates were pooled and assayed in triplicate. The standard error for each set of assays was generally less than 10%. Activities were normalized for cell density, and the relative activity of each promoter is presented as the percentage of the induced activity obtained with a wild-type promoter control run in parallel with each set of assays.

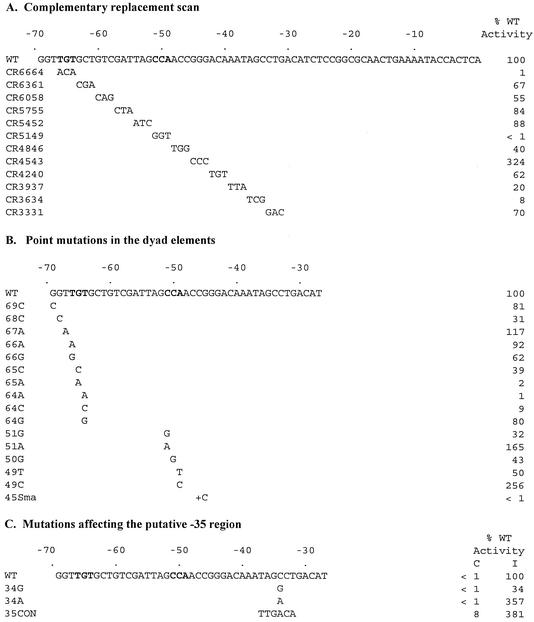

FIG. 2.

Effects of mutations in the upstream region of the P2 F promoter on activation by P4 Delta. β-Gal activities are expressed as a percentage of the induced level of expression from the wild-type promoter. Activity with the chemiluminescent substrate is measured in light units; the wild-type-induced activity in these assays averaged 29,187 U, while the background activity of the wild-type promoter in the absence of Delta averaged 165 U. Nucleotides corresponding to the conserved element of dyad symmetry are indicated in bold. (A) Effects of replacing sequence with 3-nucleotide blocks of cDNA; (B) effects of selected point mutations in or near the conserved nucleotides in the dyad symmetry element; (C) effects of mutations in the putative −35 region. In panel C, the activities for both constitutive (C) and induced (I) expression are shown. Again, values are normalized to those for the induced wild-type promoter.

Binding of Delta and several related activators has been shown to protect an upstream region of PF between positions −43 and −72 from DNase I cleavage (9, 10, 17). Previous deletion analysis indicated that activation was not impaired by alterations at the 5′ end of this region up to position −69 (8). Between positions −69 and −43, the only substitutions that severely impaired activation by Delta were those that affected nucleotides within the dyad repeat elements at positions −66 to −64 and positions −51 to −49 (Fig. 2A and B). Replacement of all 3 nucleotides in either half site with complementary sequences reduced activity at least 100-fold. Replacement of blocks of 3 nucleotides in the region between the dyad elements with complementary sequences resulted in a reduction in activation of less than twofold. Substitution of individual nucleotides within the conserved dyad element generally had lesser effects on activity than the 3-nucleotide replacements, although several point mutations in the upstream half site (−65A and −64A) were quite deleterious.

The PF promoter contains a noncanonical downstream half site sequence, with a C instead of an A at position −51. Substitution of an A at this position led to a modest increase in promoter activity, a result that is again consistent with the importance of symmetrical sequences in the two half sites for maximal activation.

Several substitutions downstream of the activator binding site were also found to impair promoter activity. These mutations overlapped the putative −35 region (Fig. 2C). Consistent with this identification, a point mutation at −34 that brings the sequence closer to a −35 consensus (Fig. 2C, mutant 34A) increased activation. The 34A mutant promoter still exhibited no basal activity in the absence of activator, presumably because this single-nucleotide change is not enough to allow efficient activator-independent recognition of the promoter by RNA polymerase. Replacement of the entire putative −35 sequence with the consensus sequence for σ70 recognition (Fig. 2C, 35CON) resulted in measurable basal activity, which could be stimulated still further by Delta. These observations support a model for transcription activation in which the activator bound upstream of late promoters compensates for poor σ70 contacts to allow promoter recognition by RNA polymerase. However, the activity of the 35CON promoter was still considerably less than that of the wild-type induced promoter, so compensation for poor contacts at the σ70 −35 region does not fully explain activation. Other features of the promoter (such as relatively poor predicted σ70 contacts in the −10 region) may also influence RNA polymerase binding, and we cannot rule out the possibility that an additional role for the activator in a later step of transcription initiation exists.

In the course of this study, a single base insertion was introduced at position −45 to create a SmaI site for subsequent subcloning of the activator binding region (termed the 45Sma mutation). This 45Sma mutation inactivated the PF promoter. A strict helical-phase requirement for activator binding has been demonstrated previously for the S. marcescens nuclease promoter, which is also dependent upon an Ogr-related activator for expression (23). The effect of the 45Sma mutation indicates that the position of the bound activator relative to RNA polymerase is critical for PF as well.

Two mutations increased activity in a manner that we do not currently understand. One of these is a mutation in the downstream half site, 49C, that takes this sequence even farther away from the canonical ACA (it is now CCC). The second mutation replaces the three G residues between −45 and −43 with three C residues, resulting in a run of 5 C's from −47 to −43. Neither of the promoters with these mutations shows significant activator-independent expression (data not shown). The 49C mutation does create a sequence identical to that of the PF downstream half site, CCA, located 1 bp closer to the promoter, with a spacing of 13 bp rather than 12 bp between the two dyad half sites. It is possible that this increase in spacing improves activator binding in the context of this promoter, even though the known naturally occurring sites have 12 (or in one case 11) intervening nucleotides. Another possibility is that the wild-type binding site lies at the maximum distance that allows interaction between polymerase and the activator and that moving the downstream half site 1 bp closer to the promoter improves the orientation of bound activator relative to RNA polymerase. Both of these changes might also alter the local DNA conformation in a way that improves contact between the activator and RNA polymerase, perhaps by influencing the activator-induced bending recently demonstrated for this sequence with the related protein from S. marcescens (17). Further studies will be required to elucidate the effects of these mutations.

Comparison of sequence requirements for Delta activation of P2 PF and P4 Psid.

An analysis similar to ours has previously been carried out on the P4 late promoter Psid, assaying the effects of P4 Delta protein on transcription from this promoter (21). Complementary replacement of the 3 nucleotides in each half site of the dyad element inactivated Psid, just as was observed in the present study for PF. Introduction of a −35 consensus sequence also had similar effects on both promoters. However, Psid was also inactivated by complementary replacement of a block of nucleotides in the intervening region, at a position corresponding to −57 to −55 in PF. In contrast, replacement of this block of nucleotides in PF had an effect on activation by Delta that was less than twofold. Point mutations in the downstream half site of Psid also had much more deleterious effects than the same mutations (50G and 49T) in PF, as did the 65C mutation in the upstream half site. There is no apparent sequence similarity between the binding sites in PF and Psid beyond the two 3-bp dyad elements, so it is hard to account for these observed differences. They could reflect a requirement for additional Delta contacts to stabilize binding at Psid or steric constraints on binding or bending imposed by changes in the sequence. The upstream region of Psid is more GC rich than the corresponding region of PF, which might affect DNA conformation. Interpretation of activation from Psid in vivo is further complicated by the presence of a second Delta binding site downstream, centered at −18, which has a higher affinity for Delta (20). Delta bound to the downstream site represses transcription from Psid. The effect of any mutation that lowered the affinity of Delta for the upstream site might therefore further shift the binding equilibrium to the downstream site, amplifying the observed effect. We cannot rule out the possibility that differences in the strain backgrounds between these two studies account for some of the observed differences between the two promoters, although this seems unlikely.

Correlation between activity in vivo and activator binding in vitro.

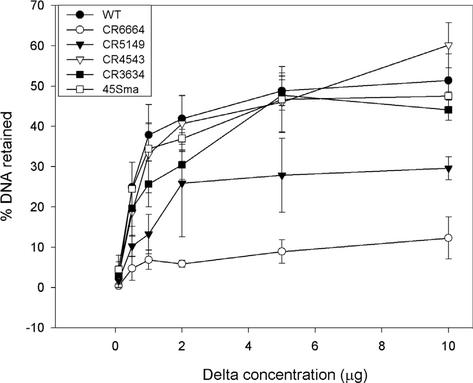

According to our working model for activation of P2 late promoters, mutations in the region between −43 and −70 exert their effects on transcription by directly affecting activator binding while mutations downstream of −43 are expected to affect polymerase binding or polymerase-activator interaction rather than binding of the activator. In order to test the effects on activator binding predicted by this model, a subset of mutant promoters was assayed directly for Delta binding by retention on nitrocellulose filters by using a mixture of Delta and MalE-Delta purified as described previously (9). The results of this analysis are presented in Fig. 3. Complementary replacement mutants CR6664 and CR5149, in which the nucleotides in the dyad half sites are changed, were expected to exert their effects on promoter activity by affecting activator binding directly. This was the case, with binding to the upstream half site mutant by Delta impaired more severely than binding to the downstream half site mutant. CR3634 also showed reduced activity in vivo but affected the putative −35 region of the promoter. Binding of polymerase rather than Delta should be impaired by this mutation. As expected, Delta binding to this mutant was indistinguishable from binding to the wild-type promoter fragment. The 45Sma mutation, which inserts a C at −45, is predicted to exert its deleterious effect by altering the relative positioning between the activator and RNA polymerase. Consistent with this prediction, no impairment of Delta binding was seen. The final mutant promoter tested was CR4543, which increases promoter activation in an unknown way. This mutant, which affects nucleotides at the downstream end of the binding site identified by DNase I protection, did not show binding that differed significantly from that of the wild-type promoter fragment.

FIG. 3.

Effects of selected mutations in the upstream region of the element of dyad symmetry on DNA binding by P4 Delta. 32P-end-labeled wild-type and PF mutant fragments were generated from the lacZ promoter fusion plasmids by PCR amplification with the universal lac primer 1212 (New England Biolabs) and a kinase-treated upstream primer corresponding to the pBR322 sequence in the vector (1204M; 5′-GCGTATCACGAGGCCCT). Labeled DNA (10 ng) was incubated in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 20 mM EDTA, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol) with various concentrations of Delta protein (0.5 to 10 μg) in 50-μl reaction mixtures at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixtures were filtered through nitrocellulose filters that were presoaked in binding buffer; the filters were then washed at room temperature with 5 ml of binding buffer, dried, and counted. Binding reactions were carried out in triplicate for each promoter.

DNase I footprinting was used to examine the correlation between the in vivo effects of individual point mutations in the upstream half site and in vitro binding by Delta. As can be seen in Fig. 4, the 67A promoter mutant, which showed only a small decrease in activity, was indistinguishable from the wild-type promoter for Delta binding over the range of concentrations tested. The 66G mutant, which exhibited moderate impairment of activity, was reduced for Delta binding. Promoter mutant 65A, which was severely defective for activity, showed no detectable Delta binding. These results provide further confirmation that mutations in the dyad half sites exert their effects on PF activity by impairing activator binding.

FIG. 4.

DNase I footprint analysis of the effects of point mutations on Delta binding. Wild-type and mutant PF fragments were excised from the lacZ promoter fusion plasmids by cleavage with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated with pBluescript SKII(+) (Stratagene) that had been cleaved with the same two enzymes. End-labeled fragments for DNase I protection analysis were generated from these plasmids by cleavage with XhoI, filling in with [α-32P]deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates by using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, and subsequent cleavage with BamHI. DNase I footprinting with a mixture of P4 Delta and MalE-Delta was carried out as described previously (9). Each reaction contained 100 fmol of end-labeled promoter fragment. The autoradiogram of the gel was scanned, and the figure was labeled by using Adobe Photoshop. The G and G+A lanes indicate the Maxam-Gilbert sequencing reactions, minuses indicate reaction mixtures to which no protein was added, and triangles indicate increasing concentrations of Delta protein (2.3, 9, and 18 μg). The numbers on the left indicate the locations of the protected regions relative to the transcription start site.

The crystal structures of a number of eukaryotic zinc finger-DNA complexes have revealed a semiconserved mode of DNA recognition between amino acids in a recognition alpha helix and a binding site consisting of three adjacent bases in the major groove of the DNA (reviewed in reference 12). While no structural information about the P2 Ogr family of prokaryotic zinc-binding transcription factors is yet available, the mutational analysis of PF reported here is consistent with a similar mode of DNA recognition. The only nucleotides absolutely essential for activation lie within the three conserved adjacent bases in each dyad half site. Unlike most eukaryotic zinc finger transcription factors, which consist of multiple zinc finger domains recognizing multiple trinucleotide binding sites, all of the Ogr-like activators except P4 Delta contain just a single potential zinc finger. Recognition of the two half sites would require zinc fingers contributed by two individual molecules. Dimerization (or higher-order oligomerization) or other monomer-monomer interactions are likely to be required to stabilize the interaction between these proteins and the DNA. Genetic evidence indicates that these activators also interact directly with the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase (24), and this interaction may further stabilize activator binding.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by American Cancer Society grant RPG-92-008-NP and National Science Foundation grant MCB9982525 (to G.E.C.) and NIH grant AI08722 (to R.C.).

Past lab members Deborah Ayers and Chao Zou constructed plasmids pDEB50 and pRTA1, respectively. We are grateful to Robert Tombes for the use of his luminometer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Casadaban, M. J., J. Chou, and S. N. Cohen. 1980. In vitro gene fusions that join an enzymatically active β-galactosidase segment to amino-terminal fragments of exogenous proteins: Escherichia coli plasmid vectors for the detection and cloning of translational initiation signals. J. Bacteriol. 143:971-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christie, G. E., and R. Calendar. 1983. Bacteriophage P2 late promoters: transcription initiation sites for two late mRNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 167:773-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christie, G. E., and R. Calendar. 1985. Bacteriophage P2 late promoters. II. Comparison of the four late promoter sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 181:373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christie, G. E., and R. Calendar. 1990. Interactions between satellite bacteriophage P4 and its helpers. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24:465-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dale, E. C., G. E. Christie, and R. Calendar. 1986. Organization and expression of the satellite bacteriophage P4 late gene cluster and the sequence of the polarity suppression gene. J. Mol. Biol. 192:793-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehò, G., S. Zangrossi, D. Ghisotti, and G. Sironi. 1998. Alternative promoters in the development of bacteriophage plasmid P4. J. Virol. 62:1697-1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dibbens, J. A., and J. B. Egan. 1992. Control of gene expression in the temperate coliphage 186. IX. B is the sole phage function needed to activate transcription of the phage late genes. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2629-2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grambow, N. J., N. K. Birkeland, D. L. Anders, and G. E. Christie. 1990. Deletion analysis of a bacteriophage P2 late promoter. Gene 95:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julien, B., and R. Calendar. 1995. Purification and characterization of the bacteriophage P4 δ protein. J. Bacteriol. 177:3743-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Julien, B., and R. Calendar. 1996. Bacteriophage PSP3 and φR73 activator proteins: analysis of promoter specificities. J. Bacteriol. 178:5668-5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Julien, B., D. Pountney, G. E. Christie, and R. Calendar. 1998. Mutational analysis of a satellite phage activator. Gene 223:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klug, A., and J. W. Schwabe. 1995. Protein motifs 5. Zinc fingers. FASEB J. 9:597-604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunkel, T. A. 1985. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:488-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanzer, M., and H. Bujard. 1988. Promoters largely determine the efficiency of repressor action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:8973-8977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, T.-C., and G. E. Christie. 1990. Purification and properties of the bacteriophage P2 ogr gene product: a prokaryotic zinc-binding transcriptional activator. J. Biol. Chem. 265:7472-7477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindqvist, B. H., G. Dehò, and R. Calendar. 1993. Mechanisms of genome propagation and helper exploitation by satellite phage P4. Microbiol. Rev. 57:683-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAlister, V., C. Zou, R. H. Winslow, and G. E. Christie. 2003. Purification and characterization of the Serratia marcescens NucC protein, a zinc-binding transcription factor homologous to P2 Ogr. J. Bacteriol. 185:1806-1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michael, S. F. 1994. Mutagenesis by incorporation of a phosphorylated oligo during PCR amplification. BioTechniques 16:410-412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pountney, D. L., R. P. Tiwari, and J. B. Egan. 1997. Metal- and DNA-binding properties and mutational analysis of the transcription activating factor, B, of coliphage 186: a prokaryotic C4 zinc-finger protein. Protein Sci. 6:892-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiter, K., H. Lam, E. Young, B. Julien, and R. Calendar. 1998. A complex control system for transcriptional activation from the sid promoter of bacteriophage P4. J. Bacteriol. 180:5151-5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Bokkelen, G. B., E. C. Dale, C. Halling, and R. Calendar. 1991. Mutational analysis of a bacteriophage P4 late promoter. J. Bacteriol. 173:37-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1987. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 153:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winslow, R. H., B. Julien, R. Calendar, and G. E. Christie. 1998. An upstream sequence element required for NucC-dependent expression of the Serratia marcescens extracellular nuclease. J. Bacteriol. 180:6064-6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood, L. F., N. Y. Tszine, and G. E. Christie. 1997. Activation of P2 late transcription by P2 Ogr protein requires a discrete contact site on the C terminus of the alpha subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 274:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xue, Q., and J. B. Egan. 1995. Tail sheath and tail tube genes of the temperate coliphage 186. Virology 212:218-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]