Abstract

Therapeutic applications for mAbs have increased dramatically in recent years, but the large quantities required for clinical efficacy have limited the options that might be used for administration and thus have placed certain limitations on the use of these agents. We present an approach that allows for s.c. delivery of a small volume of a highly concentrated form of mAbs. Batch crystallization of three Ab-based therapeutics, rituximab, trastuzumab, and infliximab, provided products in high yield, with no detectable alteration to these proteins and with full retention of their biological activity in vitro. Administration s.c. of a crystalline preparation resulted in a remarkably long pharmacokinetic serum profile and a dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth in nude mice bearing BT-474 xenografts (human breast cancer cells) in vivo. Overall, this approach of generating high-concentration, low-viscosity crystalline preparations of therapeutic Abs should lead to improved ease of administration and patient compliance, thus providing new opportunities for the biotechnology industry.

Because of their successful use in targeting distinct antigens, mAbs have become powerful therapeutic agents in the treatment of cancer, inflammatory, cardiovascular, respiratory, and infectious diseases. It has been estimated that >20% of all biopharmaceuticals currently being evaluated in clinical trials are mAbs. In general, mAb therapies require the delivery of between 100 mg and 1 g of protein per dose. Because the high end of formulation concentrations for mAbs is typically in the range of 50 mg/ml, such treatments commonly require the administration of 2–20 ml. Typically, such volumes can be given only through i.v. infusion performed in a clinical or hospital setting. A broadly applicable method of achieving the high-concentration mAb preparations required to deliver these large protein doses in a small volume appropriate for s.c. injection will likely lead to an expansion of therapeutic opportunities and an increase in patient compliance. One approach would be merely to prepare extremely high-concentration preparations of soluble mAbs, on the order of 200–250 mg/ml. However, such highly concentrated solutions often result in very high viscosity, protein aggregation, and poor overall stability. We have addressed this problem by identifying methods to prepare pharmaceutically acceptable crystalline formulations of mAbs, using several of those currently in clinical use. The therapeutic mAbs used in our studies target the cell-surface antigen CD20 (1), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (2), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (3).

To the best of our knowledge, crystalline full-length mAbs have not been explored for therapeutic use. Among ≈400 biopharmaceuticals that are either approved or in advanced clinical trials, there is only one product, insulin, that is produced and administered in crystalline form (4). Yet crystallization of macromolecule pharmaceuticals, particularly proteins, can offer significant advantages, such as high stability, streamlining of manufacturing, controlled release of activity, and high doses at the delivery site, which is especially attractive for mAb therapies (5–7). Although crystallization of full-length Abs has been a subject of significant interest for the last three decades, very few intact mAbs have ever been crystallized (8–10). The difficulty in mAb crystallization largely has been attributed to their large size, the presence of surface oligosaccharides, and a high degree of segmental flexibility. All of the previously reported methods of crystallizing mAbs have used the vapor diffusion technique. This approach yields only minute quantities of crystals, is designed to produce large crystals required for x-ray studies, and commonly uses agents unacceptable for use in humans.

We have devised batch-process methods to produce crystalline suspensions of three approved therapeutic Abs: rituximab, trastuzumab, and infliximab. Rituximab is a chimeric IgG1 κ Ig that binds the CD20 antigen on the surface of normal and malignant B lymphocytes and is used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (11). Trastuzumab is a humanized IgG1 κ Ig used to treat breast cancer through a mechanism that presumably involves binding to the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) overexpressed on these tumor cells (12). Infliximab is a chimeric IgG1 κ Ig that binds to the soluble and transmembrane forms of TNF-α for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease (13). The methods we have developed for crystallization provide crystals in high yield that show excellent physical and chemical stability as well as retention of biological activity in vitro. Furthermore, we have examined the in vivo s.c. injection of crystalline trastuzumab and infliximab suspensions. The low-viscosity, highly concentrated formulations of crystalline mAbs demonstrated an extended serum pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and high bioavailability compared with the soluble mAbs delivered i.v. Finally, we have demonstrated that the crystalline formulation of trastuzumab was effective in a preclinical model of human breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Materials. Rituximab, commercially available as Rituxan, and trastuzumab, commercially available as Herceptin, were from Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). Infliximab, commercially available as Remicade, was from Centocor. A Biosep-SEC-S-3000 HPLC gel filtration column was from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA). The Bradford protein assay reagent was from Bio-Rad. All other chemicals were reagent-grade.

General Methods. The protein content of samples was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. The crystal integrity of the proteins in the formulations was measured by comparing the size and shape of the crystals with those in mother liquor by qualitative microscopic observations. To demonstrate purity and integrity of mAbs before and after crystallization, the following techniques were used: SDS/PAGE, capillary isoelectrofocusing, size exclusion column (SEC)-HPLC, dynamic light scattering, MS, peptide mapping, and N-terminal sequencing. In addition, the total carbohydrate and monosaccharide composition and N-linked oligosaccharide profiling were determined by using Bio-Rad kits (see Methods and Results in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org).

Structure of Carbohydrate on mAb. The glycan structure of rituximab was determined by using capillary electrophoresis (CE) with laser-induced fluorescence detection after digestion with various glycosidases (14). The released glycans were analyzed after derivatization with 8-aminopyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid, trisodium salt (APTS) on a Beckman Coulter P/ACE MDQ CE system equipped with an argon-ion laser with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission band-pass filter of 520 ± 10 nm. Sequential enzymatic digestion, electrophoretic mobility, and monosaccharide composition, as well as the molecular weight of the glycans released by liquid chromatography (LC)/MS, were used to get the complete structure.

Rituximab Direct Cytotoxicity Assay. Direct cytotoxicity measures the intrinsic toxic effect of an Ab on the target cell by coincubating the target cells with different concentrations of the Ab. Cell viability is counted after coincubation with the Ab. RAJI lymphoma cells (ATCC no. CCL-86) were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and diluted to 0.5 × 105 cells per ml. A 100-μl aliquot of that culture was transferred to 1 well of a 96-well plate and cultured in the presence of various concentrations of native (soluble) and dissolved crystals of rituximab for 3 days. The number of viable cells remaining after the 3-day incubation was determined by using CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega).

Rituximab Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity Assay. RAJI lymphoma cells were cultured in growth media and diluted to 0.5 × 105 cells per ml. A 100-μl aliquot of this culture was transferred to 1 well of a 96-well plate and cultured in the presence of 25 μg/ml native or dissolved crystals of rituximab and various concentrations of human serum (as a source of complement system) for 3 days. The number of viable cells remaining after the 3-day incubation was determined with the CellTiter assay as before.

Infliximab TNF-α Neutralization Assay. TNF-sensitive L-929 mouse fibroblast cells (ATCC no. CCL-1), which were cultured in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 10% horse serum, were detached from the culture flask by trypsin digestion and diluted to 2 × 105 cells per ml. A 100-μl aliquot of the culture was transferred to 1 well of a 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C with a 5% carbon dioxide-in-air atmosphere overnight. After aspiration off the medium, 100 μl of fresh medium, supplemented with 1 μg/ml actinomycin D, 100 pg/ml TNF-α, and various concentrations of native (soluble) and dissolved infliximab crystals, was added to each well and incubated overnight before the number of viable cells was determined.

Infliximab PK Studies in Rats. Forty to 45 BBDR/Wor male rats, weighing between 200 and 250 g, were used for the study, and infliximab was given through either s.c. or i.v. routes. On day 1, rats were weighed and then given a single i.v. or s.c. injection of infliximab (8 or 80 mg/kg, at concentrations of 5 ml/kg of body weight). Blood samples were taken at 0.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 168, 336, 504, and 672 h after dosing. Blood samples were taken at the additional time points of 2 and 10 min after dosing for the i.v. group. At each time point, six rats were bled from the tail, and ≈100 μl of whole blood was collected. The collected blood was processed as described above, and the levels of infliximab were determined by ELISA.

Infliximab ELISA Protocol. The wells of 96-well high-binding polystyrene plates were coated with 50 μl per well of 10 μg/ml anti-human Ab (Pierce) at 4°C overnight. The anti-human Ab was removed, and the plates were washed three times with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.138 M sodium chloride, 0.0027 M potassium chloride, and 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST). After blocking with 3% nonfat dry milk in TBST for 2 h at room temperature, a 100-μl aliquot of control (either saline or nonspecific IgG) or a diluted serum sample containing infliximab was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with TBST three times, a 100-μl aliquot of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human Ab (1:25,000 dilution with nonfat dry milk in TBST) then was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 1 h. The color reaction was initiated by adding 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate to each well and was allowed to proceed for 30 min at room temperature in the dark before it was stopped with 100 μl of 0.5 M sulfuric acid. The optical density was read at a wavelength of 450 nm (OD450) on an automatic microplate reader. The OD450 values, which corresponded to the amount of infliximab in the blood sample tested, then were plotted.

Histochemistry of Crystalline Trastuzumab in BALB/c Mice. After 12, 24, 48, and 504 h after injection of 0.1 ml of 200 mg/ml trastuzumab crystals or carrier buffer (negative control) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS purified from Escherichia coli; 50 μg in 0.1 ml of saline; positive control), the injection sites were isolated for necropsy. Any gross pathology or evidence of formulation at the injection site was noted for each of the three mice per group. A portion of the skin was fixed in neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin/eosin for histology examination for inflammatory responses. The skin of the injection site was subdivided into epidermis, dermis, and s.c. panniculus to make evaluation more concise. There were no treatment-related microscopic effects. All tissues from treated animals [skin (at injection site), brain, bladder, eyes, brown fat, white fat, testes, epididymis, heart, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, kidneys, liver, lungs, pancreas, thyroid, spinal cord, spleen, lymph nodes (cervical), thymus, esophagus, bone (femur), skeletal muscles (including psoas)] were found to be within normal limits and/or had incidental findings noted equally in controls and known to be common incidental findings for this age, sex, and strain of mouse.

Trastuzumab Efficacy Study in Nude Mice. Human breast cancer BT-474 cells, which overexpress human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) on their surface and are inhibited by anti-HER2 Ab, from ATCC were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10% NCTC 109 medium, and 1.2 mM oxaloacetic acid. After a few cell passages, the human breast cancer cells were inoculated s.c. (5 × 107 cells per animal) in the hind thighs of 3-month-old female athymic mice. Before inoculation, mice were primed for 10–14 days with 17β-estradiol applied s.c. in a biodegradable carrier-binder (1.7 mg of estradiol per pellet) to promote growth of the estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells. Crystalline trastuzumab suspensions and control solutions (nonspecific IgG) were administered s.c. in 10 doses over 5 weeks. The tumor nodules were measured every 3–4 days with vernier calipers. Mice were killed and processed for pathological and histopathological examination at the end of the treatment.

Results and Discussion

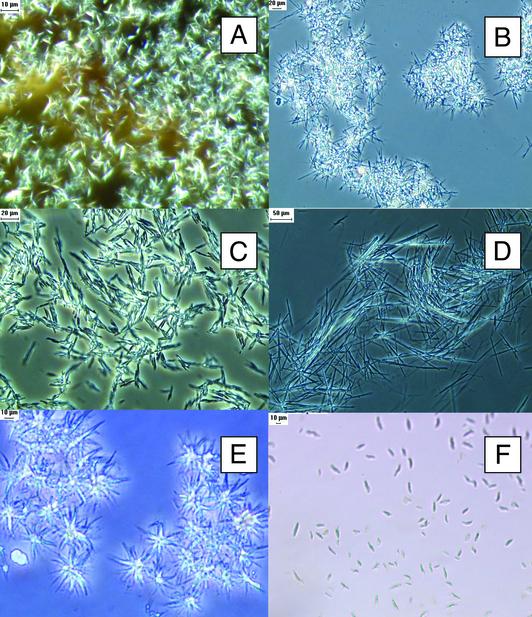

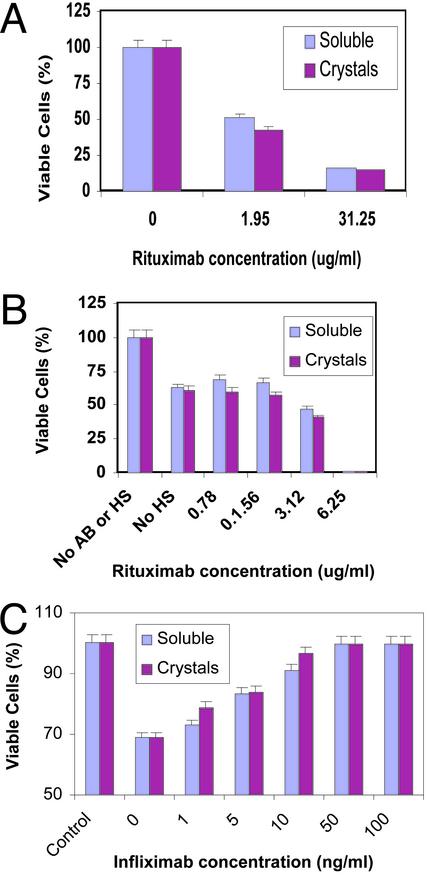

Three commercially available therapeutic mAbs, rituximab, trastuzumab, and infliximab, were successfully crystallized in large batches. Our batch crystallization protocols for these three mAbs resulted in yields of >90% for rituximab and >85% for trastuzumab and infliximab (Fig. 1). Manipulation of these protocols resulted in a variety of crystal morphologies that included needles and rice-shaped and star clusters. Analytical characterization of crystalline suspensions upon dissolution at 25°C was performed by using SDS/PAGE, isoelectrofocusing, dynamic light scattering, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS, peptide mapping, N-terminal sequencing, and carbohydrate analysis (see Figs. 7–16, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These studies showed no differences in purity and integrity between the soluble protein currently administered clinically (used in the preparation of our crystalline suspensions) and protein obtained after dissolution of these crystalline suspensions. The crystalline mAbs were dissolved easily in either water or saline in less than a minute. Moreover, crystalline samples of rituximab (10 mg/ml in mother liquor at room temperature) and trastuzumab (22 mg/ml in mother liquor at 4°C) exhibited complete retention of native state as determined by size exclusion column HPLC (no aggregation or fragments) after 12 months of storage at room temperature and 20 weeks at 4°C, respectively. The bioactivity of crystalline mAb preparations was evaluated in both direct and complement-dependent cytotoxicity tests (1) by using RAJI lymphoma cells in vitro for rituximab (Fig. 2 A and B) and in a TNF-α neutralization assay in the cultured fibroblast cells (Fig. 2C) for infliximab. Both tests demonstrated a similar bioactivity of mAbs before and after crystallization.

Fig. 1.

Crystals of rituximab (A and B), trastuzumab (C and D), and infliximab (E and F). Crystallization protocols are described elsewhere (15). Crystals were produced in 400-μl batches with the following precipitants: 12% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 400, 1.17 M Na2SO4 in 100 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.7 (A); 35% PEG 400, 0.2 M CaCl2 in 0.1 M Hepes buffer, pH 7.5 (B); 25% PEG 400, 5% PEG 8000, 10% propylene glycol, 0.1% Tween 80 in Tris buffer, pH 8.5 (C); 20% PEG 400, 10% PEG 8000, 10% glycerol in 0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 7.0 (D); 20% PEG 300, 5% PEG 8000, 10% glycerol in 0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 7.0 (E); and 0.2 M NaCl, 10% isopropanol in 0.1 M Hepes buffer, pH 7.6 (F). Crystals were examined under an Olympus BX60 microscope equipped with a DXC-970MD 3CCD color video camera with camera adapter (CMA D2) and analyzed with image-pro plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Samples of protein crystals were covered with a glass coverslip, mounted, and examined under ×10 magnification by using an Olympus microscope with an Olympus UPLAN F1 objective lens ×10/0.30 PH1 (phase contrast).

Fig. 2.

In vitro bioactivity of rituximab. Cultured RAJI lymphoma cells were detached, diluted to 0.5 × 105 cells per ml, and added to 96-well plates (100 μl per well). (A) Direct cytotoxicity studies were performed by incubating RAJI lymphoma cells for 3 days in the presence of various concentrations of rituximab or dissolved crystals of rituximab (added in 25-μl volumes). (B) Complement-dependent cytotoxicity was determined by exposing a mixture of RAJI lymphoma cells and rituximab preparations (as in A), followed by the addition of various concentrations of human serum. (C) In vitro bioactivity of infliximab. Cultured L-929 mouse fibroblast cells were detached, diluted to 2 × 105 cells per ml, and added to 96-well plates (100 μl per well). TNF-α neutralization assays were performed by incubating mouse fibroblast cells overnight in the presence of various concentrations of infliximab or dissolved crystals of infliximab. The number of viable cells was determined by using a CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega).

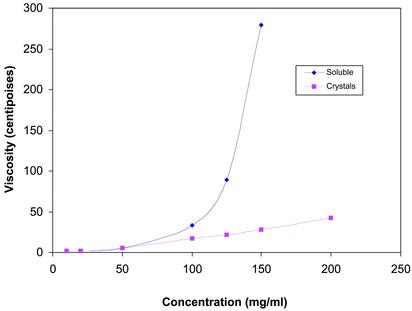

To determine whether mother liquor could be replaced with another pharmaceutically acceptable vehicle, a number of injectable vehicles were tested. We found that the PEG/ethanol mixtures are useful in providing low-viscosity formulations that maintain both crystallinity and integrity of mAbs for a long time. For example, a 200 mg/ml suspension of crystalline trastuzumab in PEG/ethanol did not show any aggregation, as assessed by size exclusion column HPLC over a period of 20 weeks at 4°C. Normally, protein solutions become quite viscous at concentrations of >100 mg/ml (S. J. Shire, unpublished communication). Yet, even at 200 mg/ml, the viscosity of the crystalline suspensions of infliximab (Fig. 3) and trastuzumab remained low and allowed for easy injection with a 26-gauge needle. (The time required to pass a 1-ml suspension of infliximab was <20 sec; for trastuzumab it was only 5 sec.) To provide a uniform suspension for accurate dosing, the crystalline formulations were mixed by inverting the vials before injection.

Fig. 3.

Viscosity measurements of infliximab. The viscosity of soluble and crystalline suspensions of infliximab was measured by using the Cannon-Fenske (State College, PA) viscometer according to the manufacturer's instructions. Commercially available infliximab [100 mg per vial containing 500 mg of sucrose, 0.5 mg of polysorbate 80, 2.2 mg of monobasic sodium phosphate (monohydrate), and 6.1 mg of dibasic sodium phosphate (dihydrate)] was reconstituted in water to concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 100, 125, and 150 mg/ml and compared with various concentrations of crystalline suspensions. The excipients in the commercial lyophilized formulation did not contribute significantly to the viscosity of the reconstituted infliximab. Even at 150 mg/ml, the viscosity of the vehicle was only 26 centipoise (cps; 1 cps = 10–3 Pa·sec), compared with 275 cps for soluble infliximab. For crystalline suspensions of infliximab, a 200 mg/ml solution (which was in formulation buffer containing 10% ethanol, 10% PEG 3350, 0.1% Tween 80, and 50 mM trehalose in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) was tested for viscosity in addition to the concentrations mentioned above for soluble infliximab.

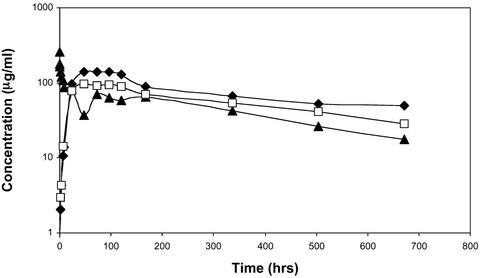

Crystalline infliximab injected s.c. into BBDR/Wor rats at a dose of 8 mg/kg was found to produce an extended serum PK profile compared with similar s.c. or i.v. injections with the commercially prepared soluble form of this mAb (Fig. 4). The crystalline mAb appeared to take longer to enter the bloodstream, achieving a lower calculated maximum concentration (Cmax) value (112 μg/ml, compared with 280 μg/ml injected by i.v. route) and significantly longer (2.9×) half-life. In comparison with i.v. injections, s.c. injections of crystalline preparations of mAbs resulted in an apparent increase in total area under the curve (AUC0-t; 42.8 mg·h·ml–1 s.c. vs. 29.6 mg·h·ml–1 i.v.), thus indicating high bioavailability. More extensive PK studies will be necessary to determine whether the apparent increase in the AUC is due to the properties of crystalline suspensions or s.c. route of administration (16), or whether it simply reflects variance in sample analysis. At the same time, we have demonstrated the integrity of the native Abs in blood samples by Western blotting as well as by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight analysis (data not shown). The results indicated that there were no Ab degradation products that would have contributed to higher ELISA values and thereby artificially increased the AUC.

Fig. 4.

PK studies of infliximab. Approximately 100 μlofinfliximab (20 mg/ml) was administered to BBDR/Wor rats having a body weight of ≈250 g to provide a dose of 8 mg/kg. The mAb was administered in a soluble form either i.v. (▴) or s.c. (□) or as a crystalline suspension s.c. (⋄). The maximum concentration (Cmax) for soluble infliximab was 257 μg/ml for the i.v. sample and 95 and 112 μg/ml for the s.c. soluble and crystalline samples, respectively. The half-life of soluble infliximab was 270 h for the i.v. sample; the half-life of the s.c. soluble and crystalline infliximab was 390 and 779 h, respectively. The total area under the curve (AUC0-t) for soluble infliximab was 29.3 mg·h·ml–1 for the i.v. sample and 37.5 and 42.8 mg·h·ml–1 for the soluble and crystalline s.c. samples, respectively.

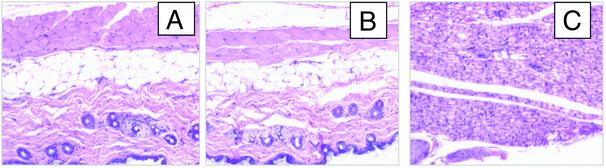

Injection site assessment was performed 12, 24, 48, and 504 h after s.c. injection of 0.1 ml of a 200 mg/ml crystalline trastuzumab suspension into BALB/c mice. The results for a 12-h time period for crystalline trastuzumab (800 mg/kg), soluble trastuzumab (30 mg/kg) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are shown in Fig. 5 A, B, and C, respectively. Crystalline and soluble protein had minimal effects over the same time period, whereas LPS, used as a positive control, had the highest incidence and the greatest severity grades for mononuclear infiltration at the injection site. Histological analysis of injection sites of animals dosed with crystalline suspensions of mAbs did not reveal residual crystals after 12 h, suggesting a rapid dissolution of crystals within the s.c. space. In addition, all tissues from treated animals were found to be within normal limits and/or had incidental findings noted equally in controls and known to be common incidental findings for this age, sex, and strain of mouse.

Fig. 5.

s.c. injection site analysis for trastuzumab. Injection sites were isolated at necropsy 12 h after the injection of 0.1 ml of 200 mg/ml trastuzumab crystals in a formulation buffer, which is different from the mother liquor, containing 10% ethanol and 10% PEG 3350 (800 mg/kg of body weight; A), 0.1 ml of a 7.5 mg/ml soluble commercial formulation of trastuzumab (30 mg/kg; B), or lipopolysaccharides (LPS; positive control; C). A portion of the skin at the site of injection was fixed in neutral buffered formalin oriented with the internal surface on a cassette-size square of paper, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned for histology. Paraffin sections were processed through hematoxylin/eosin stain. (All micrographs shown are ×40.)

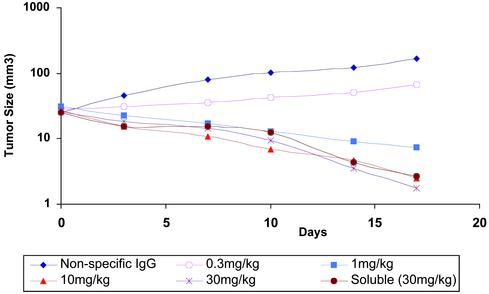

The efficacy of crystalline trastuzumab was examined in a series of experiments conducted in nude mice bearing BT-474 xenografts (17). Crystalline suspensions of trastuzumab, given s.c. at doses from 1 to 30 mg/kg (0.1 ml) twice a week for 4 weeks, induced a dose-dependent inhibition of growth of the BT-474 xenografts (Fig. 6). More pronounced antitumor activity was seen at doses >1mg/kg, with complete tumor eradication in two of six mice treated at 10 mg/kg and in three of six mice treated with 30 mg/kg. The magnitude of the effects was similar to those achieved by i.v. injection of the soluble trastuzumab (18). All tumors in the control group receiving a nonspecific IgG enlarged during this period (Fig. 6). Crystalline Ab suspensions were well tolerated and comparable with those of soluble Ab formulations.

Fig. 6.

In vivo bioactivity/efficacy of trastuzumab in nude mice. Human breast cancer BT-474 cells were used to establish tumor nodules that could be monitored by measuring their dimensions every 3–4 days with vernier calipers. Animals were placed randomly into treatment groups (n = 6). Tumor volume was calculated by the formula π/6 × [larger diameter × (smaller diameter)2]. Ab treatments were initiated when tumors became >20–30 mm3 in size in one set of animals. Crystalline trastuzumab suspensions and control solutions (containing a nonspecific IgG also at 30 mg/kg) were administered s.c. in 10 doses over 5 weeks (2 doses per week). Mice then were killed for pathological and histopathological examination and compared with the untreated animals (not injected with BT-474 cells). The mean of each experimental group is shown. Statistical significance of data comparing vehicle to anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) was determined by using one-way ANOVA software (Microsoft excel).

In summary, our data support the potential application of crystalline suspensions of mAb therapeutics for the generation of high-concentration, low-viscosity formulations for s.c. administration that rapidly dissolve after injection. This approach is commercially feasible; proteins can be batch-crystallized with good yields into a range of small crystals that demonstrate excellent physical/chemical protein stability upon storage with full retention of biological activity. Once crystallized, mAbs can be concentrated into high-concentration suspensions that are biologically compatible when injected s.c. The s.c. administration of crystalline mAbs is efficacious and potentially can reduce the frequencies of dosing. Our data suggest that the application of crystalline suspensions for the administration of therapeutic mAbs can provide a great benefit to the biotechnology industry when a high concentration of delivered protein is desired. For example, mAb therapy often can be efficacious and safe for chronic therapies, but patient compliance for i.v. infusions at a clinic can limit these uses. Additionally, some mAbs are being examined in combination therapies, often with new, orally active drugs that would make frequent visits to a clinic for an i.v. infusion unacceptable. Overall, our studies show that crystalline suspensions provide an improved method of delivery for mAbs that would otherwise be difficult to administer via the s.c. route.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Randall Mrsny for fruitful discussion and review of the manuscript. The member who communicated this article serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Altus Biologics and holds stock in the company.

Abbreviations: TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; PK, pharmacokinetic; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

References

- 1.Flieger, D., Renoth, S., Beier, I., Sauerbruch, T. & Schmidt-Wolf, I. (2000) Cell. Immunol. 204, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel, S. A., Shealy, D. J., Nakada, M. T., Le, J., Woulfe, D. S., Probert, L., Kollias, G., Ghrayeb, J., Vilcek, J. & Daddona, P. E. (1995) Cytokine 7, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietras, R. J., Poen, J. C., Gallardo, D., Wongvipat, P. N., Lee, H. J. & Slamon, D. J. (1999) Cancer Res. 59, 1347–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brange, J. & Volund, A. (1999) Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 35, 307–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shenoy, B., Wang, Y., Shan, W. & Margolin, A. L. (2001) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 73, 358–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margolin, A. L. & Navia, M. A. (2001) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 40, 2204–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jen, A. & Merkle, H. P. (2001) Pharm. Res. 18, 1483–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris, L. J., Larson, S. B. & McPherson, A. (1999) Adv. Immunol. 72, 191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuznetsov, Y. G., Day, J., Newman, R. & McPherson, A. (2000) J. Struct. Biol. 131, 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saphire, E. O., Parren, P. W., Barbas, C. F., III, Burton, D. R. & Wilson, I. A. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. D 57, 168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hainsworth, J. D. (2002) Semin. Oncol. 29, 1 Suppl. 2, 25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leyland-Jones, B. & Smith, I. (2001) Oncology 61, Suppl. 2, 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keating, G. M. & Perry, C. M. (2002) BioDrugs 16, 111–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma, S. & Nashabeh, W. (1999) Anal. Chem. 71, 5185–5192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenoy, B., Govardhan, C. P., Yang, M. & Margolin, A. L. (2002) Patent Cooperation Treaty WO 02/072636 A2.

- 16.Ghetie, V. & Ward, K. S. (1997) Immunol. Today 18, 592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colbern, G. T., Hiller, A. J., Musterer, R. S., Working, P. K. & Henderson, I. C. (1999) J. Inorg. Biochem. 77, 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baselga, J., Norton, L., Albanell, J., Kim, Y. M. & Mendelsohn, J. (1998) Cancer Res. 58, 2825–2831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.