Abstract

Ca2+ is released from the vacuole into the yeast cytoplasm on an osmotic upshock, but how this upshock is perceived was unknown. We found the vacuolar channel, Yvc1p, to be mechanosensitive, showing that the Ca2+ conduit is also the sensing molecule. Although fragile, the yeast vacuole allows limited direct mechanical examination. Pressures at tens of millimeters of Hg (1 mmHg = 133 Pa) activate the 400-pS Yvc1p conductance in whole-vacuole recording mode as well as in the excised cytoplasmic-side-out mode. Raising the bath osmolarity activates this channel and causes vacuolar shrinkage and deformation. It appears that, on upshock, a transient osmotic force activates Yvc1p to release Ca2+ from the vacuole. Mechanical activation of Yvc1p occurs regardless of Ca2+ concentration and is apparently independent of its known Ca2+ activation, which we now propose to be an amplification mechanism (Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release). Yvc1p is a member of the transient receptor potential-family channels, several of which have been associated with mechanosensation in animals. The possible use of Yvc1p as a molecular model to study mechanosensation in general is discussed.

Mechanosensitive (MS) ion channels, those that respond directly to mechanical forces, are generally believed to underlie the detection of touch, texture, balance, vibration, limb location, and osmotic pressure (1). In eukaryotes, several types of channels have been associated with mechanosensation, including the ENaC-like “degenerins” (2), the two-pore-domain K+ channels TREK and TRAAK (3), and several members of a class of channels called Trps (after transient receptor potential, the founding member in Drosophila phototransduction). Trp is now a large family that encompasses channels of diverse functions from the receptors of heat, vanilloid, and menthol to possibly the store-operated channels (4). Among Trp-family channels, Osm9 (5), no mechanoreceptor potential C (nompC) (6), stretch inhibitable channel (SIC) (7), polycystin-2 (PC2) (8), and vanilloid receptor-related osmotically activated channel (VR-OAC) (9) are associated with mechanosensitivity in different animals. In prokaryotes, the MS channels MscL and MscS have been cloned, expressed, and crystallized (10–13). Because they maintain full mechanosensitivity in lipid bilayers and their activities are readily registered by patch-clamp, they have become biophysical models with which to examine the transduction between force and conformation changes (14–16).

A force of great concern to free-living unicells is the osmotic pressure, which changes greatly on the condensation or dilution of their milieu. MscL and MscS function as safety valves to jettison cellular osmotica on osmotic downshock. Whereas wild-type Escherichia coli survives transfer to distilled water (17), a five-fold osmotic dilution toward a common culture medium lyses mscLΔ mscSΔ bacteria (11). In the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a cascade of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase underlies yeast's long-term adaptation to the increase in osmolarity (18). Genetic and biochemical dissection pointed to Sln1p and Sho1p as the putative osmosensors in this cascade (19–21). However, how these putative sensors detect osmotic changes has never been proposed and remains entirely obscure (22). In response to acute osmotic upshock, both the yeast cell and its vacuole(s) shrink (23, 24). At the same time, Ca2+ is released from the vacuole into the cytoplasm (25). We cloned and examined Yvc1p, an ≈400-pS Trp-like Ca2+-permeable channel (26), which was found to be the conduit for this upshock-induced Ca2+ release (25). Despite the fragility of isolated vacuoles, we have examined the effect of mechanical and osmotic pressure on them and discovered that Yvc1p is in fact MS. Thus, the simplest model is that the temporary osmotic imbalance generates a force that stretches open Yvc1p to release vacuolar Ca2+. Yvc1p is, thus, a microbial Trp channel that demonstrates such a property in situ. Here we report this finding and describe our investigation of the role of Yvc1p in the physiological responses to osmotic upshock.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains. YVC1 (wild-type parental strain): BY4742 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ lys2Δ ura3Δ), and yvc1Δ (YVC1 chromosomal-knockout strain; YVC1:km): BY4742 containing a complete chromosomal replacement of the entire YVC1 with a kanamycin resistance gene (26).

Molecular Biology. pYVC1-His was generated by PCR from YVC1-HA (26), attaching an XmaI site to the 5′ end of the YVC1 coding sequence and a 10-His tag, the stop codon, and an XhoI site to the 3′ end. The 5′ primer was as follows: 5′-TCC CCC GGG ATG GTA TCA GCC AAC GGC GAC TTG CAC TTG-3′. The 3′ primer was as follows: 5′-CCG CTC GAG CGG TTA GTG ATG ATG ATG ATG ATG ATG ATG ATG ATG CTC TTT CTT ATC CTT TAT GTC-3′. The fragment was force cloned (XmaI/XhoI) into p426GALL (American Type Culture Collection) and subsequently force cloned into the same sites in p416GALL (American Type Culture Collection). The gene product was fully sequenced in the p426GALL plasmid and was checked for correct insertion in p416GALL, and pYVC1-His was electroporated (Bio-Rad) into yvc1Δ.

Electrophysiology. Vacuoles were generated as described (27, 28). The procedure entails an overnight culturing of the spheroplasts, in which the multivesicular looking vacuole(s) in each logarithmic-phase cell (ref. 29; Fig. 5) became a single spherical vacuole. The spheroplasts with their individual vacuoles were then swollen by hypoosmolarity to shed their plasma membranes so as to expose the vacuoles for patch-clamping as reported (26). The pipet solution contained 180 mM KCl and 0.1 mM EGTA and the bath solution contained 100 mM potassium citrate. CaCl2 was added for the desired free [Ca2+] according to Marks and Maxfield (30). All solutions also contained 5 mM Hepes and were adjusted to pH 7.2 except for that used in the experiment shown in Fig. 1C, which contained 5 mM Mes, pH 6.0. We have experimented with different methods of changing bath osmolarity. For exploration, an osmoticum in stock solution was gently added to the bath with a micropipet within 1 cm from the vacuole under patch-clamp. For rapid changes of the bath, 1 ml of hyperosmotic solution was added to one side of the 1-ml bath solution before 1 ml of bath was removed from the opposite side, all within a few seconds (Fig. 3). Although the final concentration of the bath was not certain, this method ensured rapid solution changes. Our experience of >50 trials indicated that slower osmolarity changes were less effective. A rapid perfusion system that does not rupture the preparation has yet to be developed.

Fig. 5.

Hyperosmotic shock activates Yvc1p. (A) As depicted in Inset, a wild-type vacuole clamped at -20 mV and equilibrated at 0.4 osmolar was subjected to an osmotic upshock by the addition of 1.5 osmolar solution <1 cm away (arrowhead). Bath, 10-5 M Ca2+. The vacuole shrank and showed the ≈400 pS activities within seconds. The conducting ions were held constant and the added osmoticum was sorbitol. (B) An amplitude-histogram analysis of 15 sec of current in A, beginning 6 sec after the arrowhead. Current amplitude distributes in bins of uniform increments, ruling out the response to the osmotic upshock being nonspecific artifacts of the patch.

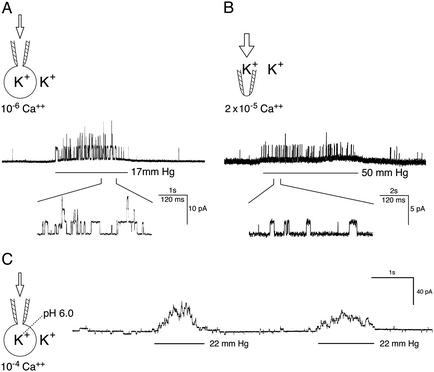

Fig. 1.

The Trp-like channel Yvc1p in the wild-type yeast vacuolar membrane is MS. (A) Recording in whole-vacuole mode. A 2.6-sec pressure pulse (see bar under trace and arrow in cartoon) at 17 mmHg applied into a vacuole of the wild-type activates the ≈400-pS unitary conductances. Five hundred msec of the patch's response is presented at a faster time base to show the clear flat-top nature of individual open episodes. In this and following figures, upward traces indicate current flowing from the vacuole into the cytoplasmic side. The bath (cytosolic side) contained 10-6 MCa2+ in which there is little channel activity before or after the pressure pulse. Voltage was held at -25 mV, cytoplasmic-side negative. (B) Patch-clamp recording in cytoplasmic-side-out excised-patch mode. The bath contained 2 × 10-5 MCa2+ and voltage was held at -18 mV. (C) Whole-vacuole recording with pH 6.0 pipet fillant to simulate the acidic vacuolar lumen. The bath contained 10-4 Ca2+ and voltage was held at -16 mV. Note that a larger pressure, 50 mmHg, was applied to the patch (B) than to the vacuole (A and C).

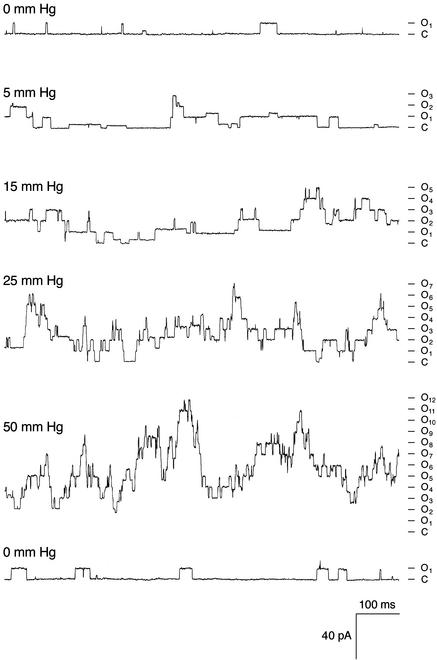

Fig. 3.

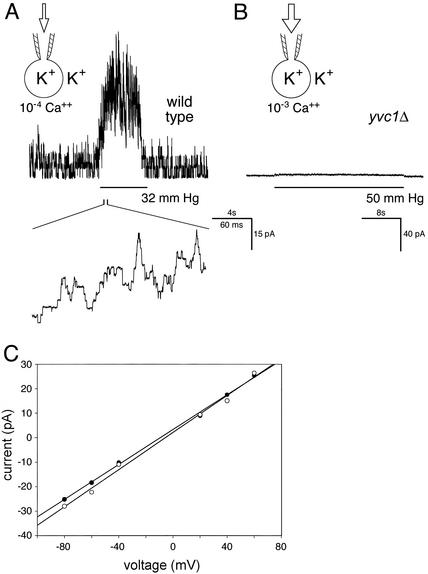

Mechanosensitivity of Yvc1p does not depend on Ca2+ concentration. (A) Recording in the whole-vacuole mode. A wild-type vacuole bathed in a solution containing 10-4 M Ca2+. Note the activities of several units even before or after the pressure pulse at this high [Ca2+] (compare with Fig. 1 A). Pressure application clearly activated more channel units. Voltage was held at -20 mV. (B) Recording from a vacuole of a knockout strain, yvc1Δ, showing no current responses to the application, even at a very large pressure and at 10-3 M [Ca2+]. (C) Current–voltage plots showing that the unitary conductances observed in high [Ca2+] and on pressure are almost identical. The single-channel currents from a wild-type vacuole bathed in 10-5 M Ca2+ were measured at different voltage (filled circles). This solution was then replaced with one with 10-6 M Ca2+, in which the vacuole showed no activity. A pressure of >10 mmHg was then applied and the currents at different voltages were again measured (open circles). Linear regression by Sigma Plot showed the conductance to be 356 pS (•) and 378 pS (○).

Results

Yvc1p Is MS. With osmotic manipulations, yeast spheroplasts can shed their membranes and expose their vacuoles. The released vacuoles can then be examined by using a planar bilayer or a patch-clamp pipet. An ≈400-pS cation conductance has repeatedly been observed (27, 28, 31) that is activated by Ca2+ presented from the cytoplasmic side. We cloned the TRP homolog YVC1 of yeast and showed that it is required for this conductance (26). It had been tacitly assumed that the isolated vacuoles were too fragile for direct mechanical examination. Nonetheless, we found them to withstand tens of millimeters of Hg of pressure delivered through the recording pipet, and we discovered that such pressures activate this conductance. This conductance can be observed in either the whole-vacuole recording mode (Fig. 1A) or the excised cytoplasmic-side-out recording mode (Fig. 1B). The open probability increases immediately at the onset of the pressure and recedes immediately on its release. This outcome has been observed in every one of >50 vacuoles where whole-vacuole recording mode was clearly established. For each such vacuole, every one of >10 pressure pulses, on the order of tens of millimeters of Hg, activated this Yvc1p conductance. Yvc1p activation was also observed in excised patches (Fig. 1B), although larger pressures were required, as expected from the Laplace's law (n > 10). In vacuoles derived from a knockout strain, yvc1Δ, this MS conductance was never observed (Fig. 3B; n > 10). Our standard pipet fillant was at pH 7.2. By using a pipet solution at pH 6.0 to simulate the acidic vacuolar lumen (32), we found no difference in Yvc1p's mechanosensitivity (Fig. 1C; n > 5). For channels where membrane stretch force is the gating principle, their open probability (Po) increases with the mechanical energy, according to the Boltzmann distribution (33). The Po of Yvc1p clearly increases with the pressure applied to the vacuole through the patch-clamp pipet (Fig. 2, top five traces). Depending on the size of the vacuole, pressures >50 mmHg can usually activate currents of >100 units, but such currents are apparently still far from saturation. Higher pressures eventually rupture the vacuole, making it impossible to completely describe the quantitative relationship between Po and pressure here. Activities entail no lasting changes because returning to the starting conditions restores the original level of activity (Fig. 2, bottom trace) and reapplication of pressures activates the channels again (Fig. 4). Direct suctions through the recording pipet tend to break the gigaseal and/or rupture the vacuole, yielding no interpretable results.

Fig. 2.

The open probability of wild-type Yvc1p increases with the applied pressure. Whole-vacuole recording at -40 mV, 10-5M Ca2+. The applied pressures are marked on the left of each trace and the current level for number of open units is marked on the right. The time sequence is shown from top to bottom. Releasing pressure returned the patch to a state of low activity (bottom trace). Some substate activities are evident.

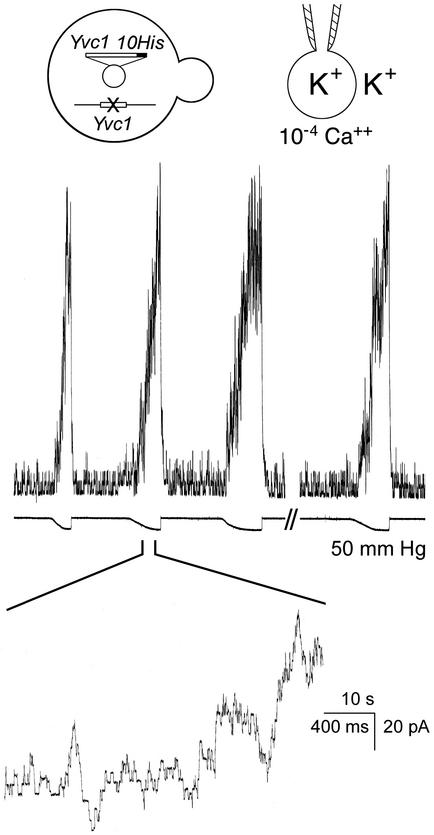

Fig. 4.

Decahistidine-tagged Yvc1p expressed from a plasmid retains the ≈400-pS unitary conductance and its mechanosensitivity. Vacuole bathed in a solution containing 10-4 M Ca2+ and held at -20 mV. Repeated pressure pulses of 50 mmHg yielded repeated channel responses from the vacuole. A gap of 52.3 sec separated episodes 3 and 4, showing no long-term effects of repeated activations.

Mechanical Versus Ca2+ Activation. We and others have previously investigated the behavior of this vacuolar channel in different [Ca2+]. Ca2+ presented from the cytoplasmic side activates it (28, 26, 31), whereas that from the luminal side inhibits it (X.-L.Z., C.P.P., C.K., and Y.S., unpublished observation). The channel activities elicited by pressure and those by cytoplasmic Ca2+ have the same unitary conductance (Fig. 3C) and disappear together on YVC1 deletion (Fig. 3B). The ≈400-pS unitary conductance of Yvc1p is ≈10 times that of the MS channel of the plasma membrane (34), or that associated with Mid1p (35). It is therefore unlikely that this conductance originates from a convolution of membranes. As seen in previous studies (26, 28), there is very little Yvc1p activity at or <10-6 M cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Fig. 1 A, before and after the pressure pulse), but the activities are clearly present in 10-4 M (Fig. 3A, before and after the pressure pulse). At or <10-7 M, there is almost no spontaneous Yvc1p activity, while pressure pulses remain potent in activating it. It therefore seems likely that the mechanical activation is independent of the concentration of Ca2+ (see Discussion).

Decahistidine-Tagged Yvc1p Expressed in Trans Remains MS. We have shown previously that YVC1 in a plasmid supports the production of the Yvc1p protein and its ≈400-pS conductance (26). In preparation for future protein purification, we have constructed an expression plasmid, pYVC1-His, in which the YVC1 insert is tagged with nucleotides that encode 10 histidines at the C terminus of Yvc1p. YVC1-null host cells were transformed with pYVC1-His and the transformants were examined. As shown in Fig. 4, the ≈40-pS conductance produced are indistinguishable from that of the wild-type yeast cells (Figs. 1, 2, 3). In whole-vacuole recording mode, pressure pulses at tens of millimeters of Hg repeatedly activated these conductances like those of the wild-type. Therefore, the addition of the histidine residues to Yvc1p does not affect the conductance and its mechanosensitivity.

Hyperosmolarity Activates Yvc1p. Challenging naked vacuoles under patch-clamp directly with an osmotic shock proves to be a delicate operation. The maneuver of changing bath osmolarity and the subsequent shrinkage of the vacuoles often dislodge them from the pipets or break the gigaseal. Nonetheless, in each of >10 cases where the experiments were successfully carried out, an increase from 0.4 to between 0.8 and 1.5 osmolar invariably activated Yvc1p (Fig. 5A). Amplitude histograms demonstrate that the response is the summation of stochastic activities of individual unitary conductances (Fig. 5B). This effect is independent of the nature of the solute, being observable with the application of salts (NaCl and KCl), as well as a sugar (sorbitol). After the addition of the osmoticum, the semitranslucent vacuole at the tip of the patch-clamp pipet invariably deforms and shrinks into an opaque lump, the detailed geometry of which cannot be resolved with the light microscope we used for patch-clamp purposes. This shrinkage indicates that vacuole's water loss is much faster than the supply from the pipet, if any; i.e., the recording pipet and the vacuole form a virtually closed hydraulic system. Both the Yvc1p activation and vacuolar shrinkage take place within seconds after the osmolarity increases near the vacuole, although the accurate time course has not been examined with ultra-fast perfusion due to technical difficulties. The Yvc1 activity peaks within several tens of seconds but subsides to a low level afterward (see Discussion). This subsidence appears much faster than the possible adaptation of the channel molecule to a constant stretch force (Fig. 4; X.-L.Z., unpublished results).

Discussion

Through molecular examination under patch-clamp (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4), Yvc1p now joins the small coterie of Trp MS channels (5–9). The MS of Yvc1p befits its role as the sensor of osmotic changes because upshock activates it (Fig. 5). Thus, the MS property of Yvc1p can explain how an osmotic upshock is transduced into a flux of Ca2+ from the vacuole into the cytoplasm (25).

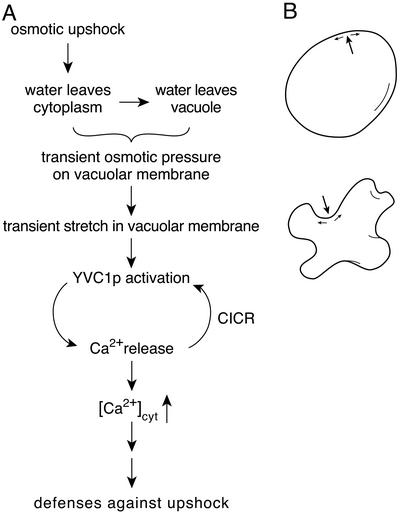

A Model of Yvc1p Activation by Osmotic Upshock. Taking all observations into account, our simplest interpretation is as follows (Fig. 6A). On upshock, water is drawn from the cytoplasm and then from the vacuole. The temporary osmotic imbalance between the two produces an osmotic pressure across the vacuolar membrane that activates Yvc1p. Eventually, the net water flux across this membrane will recede and cease, as will the osmotic pressure. The rise and fall of the Yvc1p activity (Fig. 5A) likely reflect the time course of this water flux from the vacuole to the bath (the cytoplasmic side). A pressure on the membrane (Fig. 6B, large arrows), be it mechanical or osmotic, and regardless of direction, stretches the membrane along its plane (36). This stretch force partitions the Yvc1p molecules toward their open conformation. Note that only some 3 milliosmolar difference across the tonoplast will be sufficient to generate an osmotic force of 50 mmHg in magnitude that activates a large number of vacuolar Yvc1p (Figs. 1, 2, 3). This pressure will generate a membrane tension of 5–7 mN/m in these vacuoles of 3–4 μm in diameter. Whereas the quantitative evaluation of the biomechanics above warrants confidence in Yvc1p's role as the pressure-to-flux transducer, the time course of the rise and fall of osmotic pressure across the tonoplast in vivo cannot be deduced directly from the Yvc1p activities we registered (Fig. 5). The caveats are technical: (i) The vacuoles under examination have been osmotically manipulated in their preparation for the patch-clamp experiments; (ii) The naked vacuoles under patch-clamp are confronted with upshocks directly here, instead of being buffered by the cytoplasm, the cytoplasmic membrane, and cell wall in vivo; and (iii) The time at which the hyperosmotic front reaches the patch-clamped vacuole cannot be accurately determined to within several seconds because of current technical limitations. Note that the vacuolar membrane is complex and comprises many integral and associated proteins, including actin at the surface facing the cytoplasm (37). Whether the stretch force is transmitted through interacting proteins, or directly through the lipid bilayer like MscL (10), remains to be investigated.

Fig. 6.

A model of osmotic sensing through Yvc1p. (A)A flow chart listing the key events from the rise of external osmolarity to the release of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm. (B) An illustration of how an outwardly directed pressure (e.g., by mechanical force; large arrow, Upper) or an inwardly directed pressure (e.g., by external hyperosmolarity; large arrow, Lower) can both generate tension on the membrane (small arrows), which activates the MS Yvc1p. The transient osmotic pressure in A postulated may occur very locally and does not necessarily correlate with gross changes in vacuole shape as drawn (B Lower).

Vacuolar Shrinkage and Crenellation On Upshock. On an osmotic upshock, the vacuoles shrink and crenellate (23, 24, 29, 38). Upshock apparently increases the level of phophatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate [PI(3,5)P2] (29), and the enzymes for its production, as well as other gene products, are required for the final crenellation. Mutants defective in these proteins have defective vacuolar inheritance and enlarged vacuoles with or without osmotic stress (39, 29). Other mutants have protein-sorting defects and are sensitive to osmotic stress (40–42). Using the styryl dye FM4-64 and fluorescent microscopy (29), we found the vacuoles of yvc1Δ cells to be able to shrink, although their time course has not been determined (data not shown). Thus, the activities of these enzymes and gene product apparently do not depend on Yvc1p or the Ca2+ it releases. Much more likely, the Yvc1p is activated by the stretch force (Fig. 6) during the process of deformation. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the stretch force arises very locally, e.g., from submicroscopic domains of the lipid bilayer blistering away from the protein coat, before the global crenellation. [The bilayer is permeable to water and simple liposomes deform on upshock (43)].

Complex Regulation. Yvc1p, like other Trp channels, passes cations. Given the gradients, the flux of physiological significance is that of Ca2+ entry into the cytosol. Among the sequalae of this cytosolic Ca2+ is that it increases the open probability of Yvc1p itself. Activation of Yvc1p by cytosolic Ca2+ has been demonstrated repeatedly (28, 26), which by our model (Fig. 6A) is now considered a Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), a well known positive-feedback loop in animal physiology. Whether the activation of Yvc1p by cytoplasmic Ca2+ has other roles in yeast physiology remains to be explored. Yvc1p clearly rectifies inwardly; i.e., its open probability increases with cytoplasmic negativity (with respect to the vacuole lumen), driving current into the cytoplasm. It rarely opens when the cytoplasm is positive and thus conducts little current into the vacuole (28, 26). Further, Yvc1p is sensitive to the redox state of the cytoplasm; reducing agents favor its activity (28, 26). Thus, besides being the force-to-flux transducer, Yvc1p also sums the information on transmembrane voltage, cytoplasmic [Ca2+], vacuolar [Ca2+], and the redox state to regulate its open probability, and thereby the Ca2+ flux. Much work lies ahead in dissecting this sophisticated molecule.

Yvc1p as a Model of Eukaryotic MS Channels. Yvc1p may have a functional analog in plants. In the tonoplast of sugar-beet root-tip cells, there is a large-conductance, CICR cation channel called SV (44, 45), but its possible MS and its molecular nature are presently unknown. Yvc1p clearly has structural homologs in animals and other fungi. Trp channels associated with MS include Osm9, needed for osmotic or nose-touch response in the worm (5), nompC, responsible for mechanoreceptor potential of fly bristles (6), PC2, in the primary cilia of kidney epithelium (8), and the heterologously expressed mammalian channels SIC (7) and VR-OAC (9). It seems possible to develop Yvc1p into a model system to study Trp-family MS channels. The ≈400-pS activity of Yvc1p was first discovered (31) on reconstituting yeast vacuolar membranes into planar lipid bilayers, although it is not known whether the reconstituted conductance is still MS at this writing. Reconstitutability allows further reduction of the experimental system, making hopeful a deeper molecular understanding as in the cases of MscL and MscS of E. coli. The combinatorial heterotetramerization of different Trp-channel subunits defines their function and location in animals (46). That YVC1 is the only Trp-channel gene in the entire yeast genome simplifies analysis. The budding yeast has proven to be the premier experimental system to dissect cell- and molecular-biological processes in eukaryotic cells. It should be useful and efficient to bring the prowess of yeast genetics to bear on the dissection of Yvc1p. The discovery of MS in Yvc1p and its further investigation may reveal a unifying principle of how Trp-family channels serve to detect osmotic pressure or other physical forces (1). A basic principle derived from the research on MscL and MscS is that these prokayrotic channels detect stretch forces directly transmitted from the lipid bilayer. The research on animal MS channels thus far appears to emphasize the role of proteins that attach the channel to intracellular cytoskeleton or extracellular matrix, presumably for force transmission (47). Further analysis of Yvc1p may help illuminate the possible unity and/or diversity among the force-transducing mechanisms. Meanwhile, rapid perfusion, Yvc1p-purification through the added His-tag (Fig. 4), reconstitution, and heterologous expression will be attempted to set the stage for a genetic and cell-biological dissection of this Trp channel.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM47856 (to C.K.) and GM54867 (to Y.S.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: MS, mechanosensitive; Trp, transient receptor potential.

References

- 1.Ernstrom, G. G. & Chalfie, M. (2002) Annu. Rev. Genet. 36, 411-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chelur, D. S., Ernstrom, G. G., Goodman, M. B., Yao, C. A., Chen, L., O'Hagan, R. & Chalfie, M. (2002) Nature 420, 669-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel, A. J., Lazdunski, M. & Honore, E. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 422-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montell, C., Birnbaumer, L. & Flockerzi, V. (2002) Cell 108, 595-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colbert, H. A., Smith, T. L. & Bargmann, C. I. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 8259-8269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker, R. G., Willingham, A. T. & Zuker, C. S. (2000) Science 287, 2229-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki, M., Sato, J., Kutsuwada, K., Ooki, G. & Imai, M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 6330-6335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nauli, S. M., Alenghat, F. J., Luo, Y., Williams, E., Vassilev, P., Li, X., Elia, A. E., Lu, W., Brown, E. M., Quinn, S. J., et al. (2003) Nat. Genet. 33, 129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liedtke, W., Choe, Y., Marti-Renom, M. A., Bell, A. M., Denis, C. S., Sali, A., Hudspeth, A. J., Friedman, J. M. & Heller, S. (2000) Cell 103, 525-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sukharev, S. I., Blount, P., Martinac, B. & Kung, C. (1997) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59, 633-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levina, N., Totemeyer, S., Stokes, N. R., Louis, P., Jones, M. A. & Booth, I. R. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 1730-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang, G., Spencer, R. H., Lee, A. T., Barclay, M. T. & Rees, D. C. (1998) Science 282, 2220-2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bass, R. B., Strop, P., Barclay, M. & Rees, D. C. (2002) Science 298, 1582-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perozo, E., Cortes, D. M., Sompornpisut, P., Kloda, A. & Martinac, B. (2002) Nature 418, 942-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perozo, E., Kloda, A., Cortes, D. M. & Martinac, B. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 696-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betanzos, M., Chiang, C. S., Guy, H. R. & Sukharev, S. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 704-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Britten, R. J. & McClure, F. T. (1962) Bacteriol. Rev. 26, 292-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewster, J. L., de Valoir, T., Dwyer, N. D., Winter, E. & Gustin, M. C. (1993) Science 259, 1760-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ota, I. M. & Varshavsky, A. (1993) Science 262, 566-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeda, T., Wurgler-Murphy, S. M. & Saito, H. (1994) Nature 369, 242-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeda, T., Takekawa, M. & Saito, H. (1995) Science 269, 554-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustin, M. C., Albertyn, J., Alexander, M. & Davenport, K. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1264-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vindelov, J. & Arneborg, N. (2002) Yeast 19, 429-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nass, R. & Rao, R. (1999) Microbiology 145, 3221-3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denis, V. & Cyert, M. S. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 29-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer, C. P., Zhou, X.-L., Lin, J., Loukin, S. H., Kung, C. & Saimi, Y. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7801-7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saimi, Y., Martinac, B., Delcour, A. H., Minorsky, P. V., Gustin, M. C., Culbertson, M. R., Adler, J. & Kung, C. (1992) Methods Enzymol. 207, 681-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertl, A. & Slayman, C. L. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 7824-7828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonangelino, C. J., Nau, J. J., Duex, J. E., Brinkman, M., Wurmser, A. E., Gary, J. D., Emr, S. D. & Weisman, L. S. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 1015-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marks, P. W. & Maxfield, F. R. (1991) Anal. Biochem. 193, 61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wada, Y., Ohsumi, Y., Tanifuji, M., Kasai, M. & Anraku, Y. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 17260-17263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearce, D. A., Ferea, T., Nosel, S. A., Biswadip, D. & Sherman, F. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22, 55-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinac, B., Buechner, M., Delcour, A. H., Adler, J. & Kung, C. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 2297-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gustin, M. C., Zhou, X.-L., Martinac, B. & Kung, C. (1988) Science 242, 762-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanzaki, M., Nagasawa, M., Kojima, I., Sato, C., Naruse, K., Sokabe, M. & Iida, H. (1999) Science 285, 882-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamill, O. P. & Martinac, B. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 685-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eitzen, G., Wang, L., Thorngren, N. & Wickner, W. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 158, 669-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bone, N., Millar, J. B., Toda, T. & Armstrong, J. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 135-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonangelino, C. J., Catlett, N. L. & Weisman, L. S. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6847-6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banta, L. M., Robinson, J. S., Klionsky, D. J. & Emr, S. D. (1988) J. Cell Biol. 107, 1369-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latterich, M. & Watson, M. D. (1993) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 191, 1111-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latterich, M. & Watson, M. D. (1991) Mol. Microbiol. 5, 2417-2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poolman, B., Blount, P., Folgering, J. H., Friesen, R. H., Moe, P. C. & van der Heide, T. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 44, 889-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bewell, M. A., Maathuis, F. J., Allen, G. J. & Sanders, D. (1999) FEBS Lett. 458, 41-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pottosin, I. I., Dobrovinskaya, O. R. & Muniz, J. (2001) J. Membr. Biol. 181, 55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tobin, D., Madsen, D., Kahn-Kirby, A., Peckol, E., Moulder, G., Barstead, R., Maricq, A. & Bargmann, C. (2002) Neuron 35, 307-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gillespie, P. G. & Walker, R. G. (2001) Nature 413, 194-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]